|

I never knew the doll existed until my cousin Caryle came to a family get-together recently. I took the occasion to ask about our mutual grandmother, Irish-born, whom we all called Nana.

“I can’t remember her voice,” I told Caryle. “I can’t remember anything she said.” This is bothering me more, the older I get. I should have more memories, since my large family lived in Nana’s house in Queens, but she kept to herself, and bustled around to visit her old Irish lady friends in the city or Lake George, Sometimes she visited her sister in Brussels, where that family had been decimated for sheltering Scottish soldiers during World War Two. Caryle said she had only vague memories of Nana, since her own family moved around for work, and she rarely saw Nana. “But she gave me a present once,” Caryle added, brightening. Tell me about it, I said. After one of my grandmother’s post-war trips to visit her sister, Nana gave Caryle a doll that had belonged to our aunt, Florence Duchene, who died in Bergen-Belsen. Send me a photo when you get home, I asked Caryle. She did better, adding her lovely memories of the gift: “My parents and I went to see her off on the ship, when she was going to visit her sister in Brussels,” Caryle wrote. “She said she would have liked me to come with her. Which was not possible, but meant a lot to me. “When she came back from Brussels, she brought things back with her, one of them a doll that her niece Florrie made. I have always loved dolls, I don't know if she knew that, but she gave me the doll. I still have her, she is tattered, shows her age. But she is very special to me. “I am putting her picture on this little story. See her as I have always seen her, through my eyes with love.” The doll in the photo is porcelain, a beautiful woman. Florrie, who ran a millinery shop in the good days before the war, made the frilly dress. I was stunned to see a treasure from an aunt Caryle and I never met, an aunt who has taken on epic importance to me, along with her brother Leopold, who died soon after being rescued from a Nazi prison. Leopold lived long enough to receive a king’s medal for his heroism; Florrie’s name is engraved on a monument to the Belgian Resistance, in the Ixelles area of Brussels. (I wrote about Florrie and Rue Sans Souci in March, when contemporary terrorists brutalized Brussels.) As a young woman before the war, Florrie had fussed over the doll, created her wardrobe, perhaps smoothed her blonde hair, told her secrets, her hopes and dreams. Florrie and Leopold did not live long enough to marry, to have children. Nana has been gone over 60 years, and I cannot remember if her accent reflected her native Ireland, or her husband’s native Australia, or England where they lived, or New York, where they settled. There is so much I don’t know because I was too self-centered to ask, to listen. I do remember an old lady -- formidable, capable -- with white hair and black widow’s dresses, who took me to church and the luncheonette and sometimes to the movies and we would walk home together in the wintry darkness. That’s all I remember. Now I know the doll lives in Caryle’s home. Her children know the history, Caryle said. For so many years, the schedule of a sports columnist took me far from home on the birthday of my country, on my own birthday.

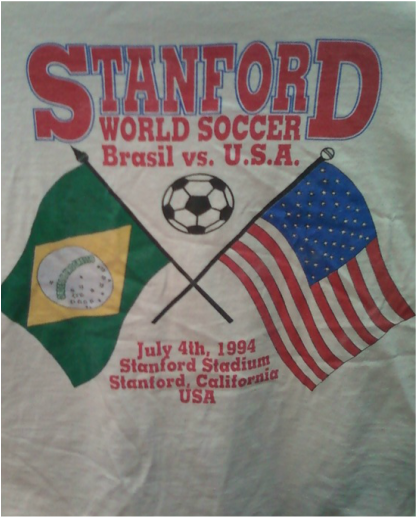

“Do you remember all the places you’ve been?” my wife asked. Sometimes she was with me. Sometimes she wasn’t. Companions get used to journalists being away -- weekends, nights, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries. My wife recalls my taking a day's drive to the mountains on our first month in Kentucky -- and being gone for New Year's after a mine blew up in Hyden. (After that, I kept a change of clothes in the car.) Reporters head toward danger, not totally unlike police and fire officers. But I was a family guy and could be hard to find by the office when a child had a big game or we had company. But sports reporters often work on scheduled events and cannot avoid being away holidays and weekends. It's easier for a man than a woman to forage for a meal on the road. In her Sunday column, Maureen Dowd describes the snooty reaction to a single female diner in a Paris hotel. Alas, her good meal was spoiled by the rancid presence of Boris and Donald in her active mind. My birthdays were often spent on the road. When I was at Wimbledon, I would scan the Times, which ran a daily box of birthdays of notables. I never expected to see my name – and never did – on July 4 but I was always happy that George Steinbrenner was a non-person in the UK, and I hoped Pam Shriver would be mentioned. I never mentioned my birthday to colleagues; why draw attention in a press room? But in the age of the blog, here are birthday highlights of a travelling journalist: 1939: Born the day Lou Gehrig delivered his farewell speech in Yankee Stadium, I was a Brooklyn Dodger fan at birth. The ‘60’s: a blur of Mets and Yanks, three children being born, great times. Was I in Minnesota…or Shea Stadium….or home? Can’t remember. 1970: We took the family to Italy for a glorious month. I can’t remember where we were on July 4 – possibly the side trip to Switzerland – but I do know that on July 9, Corinna’s birthday, my wife arranged a cake on the hotel patio, off the Via Veneto. 1976: Bicentennial Day. Now a news reporter, I was assigned to a destroyer in the Hudson, where Henry Kissinger was on board. Asked about the raid on Entebbe the night before, the Secretary of State said in his gravelly accent, “You people know more than I do.” 1982: I was alone in Barcelona, covering my first World Cup. On the night of the Third, I went to a concert by Maria del Mar Bonet in a plaza. The next day I went to El Corte Inglés and bought a vinyl record of hers, which I still play, in memory of a lonely but beautiful night. 1986: We landed in Moscow for the Goodwill Games. A grim customs agent inspected my passport and suddenly he smiled and said, “Happy birthday” in English – the start of a lovely three weeks, glasnost in summery Moscow. Wimbledon: The English always honor the Original Brexit with flags flying, burgers in pubs. I would buy a bag of cherries in Southfields and sit with a friend and listen to the military band play American music before the tennis began. 1990: We woke up in Naples after Argentina beat Italy on penalty kicks in the semifinals of the World Cup, and we took the train back to Rome, celebrating the day in the trattoria beneath our flat near the Piazza Navona. 1994: Tab Ramos was cold-cocked by Leonardo in the round of 16 at Stanford. I bought a great t-shirt with American and Brazilian flags; it recently fell apart. After dinner with Filip Bondy and Julie Vader in Palo Alto, I caught the red-eye to Boston for another match. 1998: Dennis Bergkamp scored in the 90th minute as the Netherlands beat Argentina, 2-1, in Marseilles. We were staying in Aix; my wife had gone shopping in a market for presents. 1999: A joint birthday celebration, for me and ace photographer John McDermott in San Francisco, with family, the night before steamy July 4 semi of Women’s World Cup, a 2-0 victory over Brazil. 2004: Alone in a motel in Waterloo, on the Lance watch, reading David Walsh’s book that pretty much convinced me Lance was cheating. (The masseuse who was ordered to lie about saddle sores!) Watched Greece beat host Portugal in Euro final and wrote paean to underdogs. 2005: Roger Federer beat Andy Roddick in the Wimbledon finals. Next morning we took the Eurostar to France to pick up Lance’s bid for a fifth. Two days later, we heard that nihilists had set off explosions in the London transit. 2006: In our hotel in Berlin, watched Italy beat Germany, 2-0, in semifinals, then went out in streets to interview rollicking fans, celebrating a good run with beer and curry and ever-present wurst. 2010: Jeffrey Marcus drove from cold, inland Johannesburg to the fresh salt air of Durban for the Germany-Spain semifinal two days later. My unexpected birthday present: chatty Indian staff and glorious smell of curry from the dining room -- a treat for a journalist who picked an odd day to be born. (Birthday wishes to Pam Shriver, John Hewig and John McDermott, all over the globe.) We drove up to visit Marianne's uncle Harold, 94, last October. Recently we returned. We wonder why it took us so long to discover Maine. Every time I turn the wheel, the view changes. The people are individuals. It reminds us of Wales, another singular place we love. That is high praise. Friends from Long Island invited the three of us to their stone house on an inlet. Lena made an amazing Swedish specialty from fresh salmon and eggs and dill. Claes harvested rhubarb growing since they came here. (below) Harold has been living on the same street for 70 years, since he met Barbara when he came to help dredge the Kennebec River, which flows behind his home. In between, he helped build facilities for the military. (His photos were recently displayed by nearby Bowdoin College.) About 60 years ago he gave away one of his yellow construction helmets. Recently, somebody gave it back. People have histories in Bath, Maine.

There is only one way to ponder family genealogy -- with humility, knowing that others do not know their distant past.

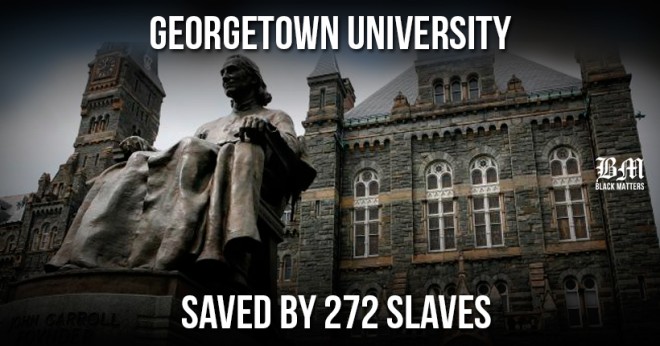

That lesson is brought home in Saturday’s New York Times, with its touching article on descendants of 272 slaves who were sold by Georgetown University in 1838 to keep that school solvent. In the article, four people in Louisiana talk about the trail of slavery with the grace of survivors, through strong families as well as the influence of the very same Catholic Church that sold them in 1838. In no small way, religion seems to have helped them, given them strength. That is the paradox. Their words, their wisdom, are a lesson to many people, including me and my wife, who can trace parts of our families back for centuries. We often feel humility toward in-laws and friends descended from Africa, as well as our Jewish friends who listen with kindness and curiosity when my wife talks about her genealogy research. We know of the gaps and absences in many lives. I can relate to some small degree because my father was adopted by a Hungarian family, his birth records sealed and apparently later destroyed by a fire in New York City. We only know his name when he was placed in an orphanage. I have always assumed he was part Jewish. I can live with that mystery, knowing of my mother’s maternal side back to County Waterford in Ireland (hence my treasured Irish passport.) My mom’s Belgian-Irish cousins were heroes in Brussels during the War.) My mother’s paternal side, Spencer, goes back to Leicestershire and later to Australia and back to England again before immigrating to the U. S. My wife has been digging into her roots in England, with help at the Mormon center in London, and lately she has been going on line into village records, as well as an ancestry web site. Over the years she has also taken information from relatives, including her grandfather, before he passed, and to this day from aunts and uncles still going into their 90’s. (Childhood farm living, no smoking, no drinking, equals longevity.) Her grandmother’s side comes through a branch of English Whipples who came into Rhode Island around 1632 and moved down to Ledyard, Conn., mingling with people named Rogers and Crouch and Watrous, many buried in the Quakertown cemetery. Her grandfather’s side traces to around Rochdale, Lancashire, in the 16th Century, with names like Grundy and Clegg and Schofield and Heywood. My wife – who spells her name Marianne – notes that many of our English ancestors had the same names – Mary Ann, Sarah, Elizabeth, Edith, George, Frederick, Arthur and John, a million Johns on my wife’s side. Sometimes she says we could be related. Aren’t we all? We have inherited little, except names and genes and mystery, along with a sense of being part of something. My wife – who loves India deeply; has been there 13 or 14 times – was told by her grandfather that a female ancestor, Sarah Schofield, had ridden an elephant in India while her husband was posted there by the colonial army in the 19th Century. She feels kinship over two centuries. None of this means much, except a sense of heritage. My wife’s people could make things with their hands; they were church-goers, people of peace, some of them abolitionists. She is still ripping mad that Spielberg’s movie, “Lincoln,” showed a Connecticut senator voting for slavery. History becomes personal all over again when we read the article by Rachel L. Swarns and Sona Patel in the Times about the good people of Louisiana, who want some tangible memorial to the 272 ancestors who were sold by a college. As we read the quotes in the Times, we feel sadness that others do not have the same reassurance of ancestors, of place, of choice, of freedom. Generally, I ascribe to the Dumpster Theory of Life. When we pass, our kids will toss all that stuff into a gigantic bin. But just as a gesture to downsizing, we were making pretensions of cleaning out the attic – something, anything.

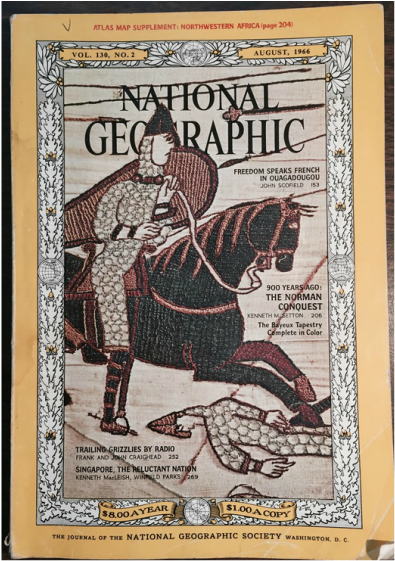

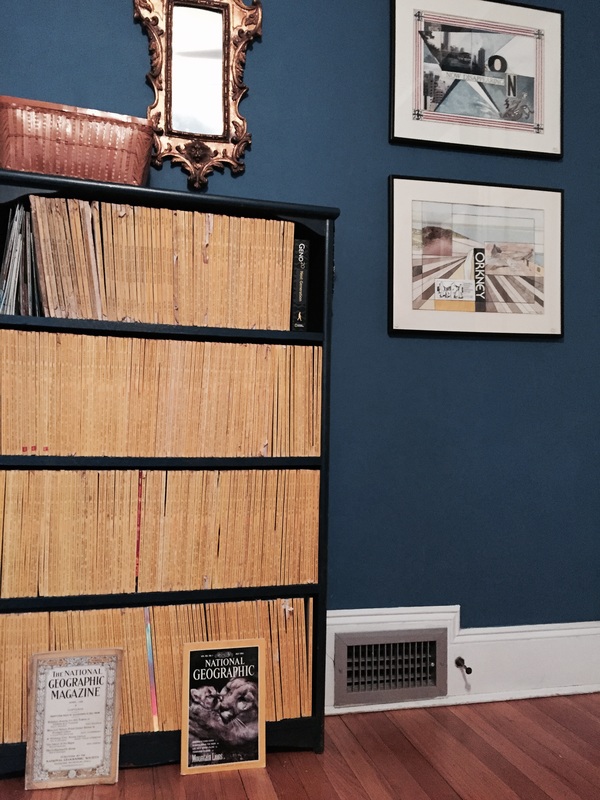

How about those National Geographics? They’ve been up in the attic for five years, maybe 10. The Web says nobody wants Geographics, not for money, not for free. Try an old-age home, the Comments say. Wait, this is an old-age home, technically. I went to the attic and put them in doubled-up shopping bags, flecking off the dust and grit. A few on the top were damp from a long-patched drip near the chimney. Ninety-nine per cent were in fine shape. I could hear the voices of the writers and the editors and, yes, the subjects – the Uighurs of China, the Zulus of Africa, the clog-dancers of Appalachia, the explorers of outer space: “Look at us. We were important then. We are important now. Get us out of the attic, to somebody who appreciates us." I lugged the magazines, 20 or so to a bag, down to the second floor. (The movable wooden stairway with its sturdy steel housing is itself a relic, from the great builder, Walter Uhl, in the mid-30’s, when homes were made to last.) I began my exploration of ancient history, chronologically: A few dozen older issues we had collected from a library sale on the North Fork of Long Island.

By 1963, we were subscribing, leaving the Geographics around, to make our children, present and future, curious about the world out there. In August 1966, shortly after my wife and I made our first Europe on $5 a Day trip to Europe, there arrived an issue with “900 Years Ago: The Norman Conquest. The Bayeux Tapestry, Complete in Color.” We saved it, of course, and in April of 1975 we took all three children to France for a month, riding the Métro and glorying in the baguettes (trés crustillant) and driving out to Normandy in a wheezing old Citroen a friend had lent me. The August, 1966, Geographic came with us and we consulted the 46 pages that explained every figure of the Bayeux Tapestry as we walked alongside it. Now the same edition of the Geographic was in my hand, bringing back memories. We could not part with these heirlooms. I painted a cabinet dark blue and soon filled it with Geographics -- May 1928 in the upper left corner, all the way to 1992, lower right. Then we put the last 15 years in a hall shelf. (We cut the subscription when our grandchildren began thumbing through smartphones instead of pages.) The National Geographic endures, bless its earnest heart. Our “collection” – approximately 600 editions – is home. I am poking through the Bayeux Tapestry, thinking of Galette Bretonne and the coast at Omaha Beach. The Dumpster can wait. As somebody who often took his children to work, I can relate to Adam Laroche, who “retired” from baseball the other day.

Laroche quit the Chicago White Sox after being told by his general manager to “dial it back” about bringing his 14-year-old son to workouts and the clubhouse every day during spring training. He has been getting support from current and former teammates, who insist baseball is a “family game.” It must be – Laroche’s father and brother have also played in the majors. Drake Laroche quite likely has great third-generation genes. It’s good to encourage people to enter the family business. I took all three of our kids on assignments with me. One of the proudest moments in my career was in 2000 during the Yankees’ playoff series in Seattle. While chatting with Bernie Williams, I looked around the clubhouse and saw our daughter, Laura, then a columnist in Seattle, chatting with her old friend, Tino Martinez, and I saw my son, David, then working for a web site, chatting with Paul O’Neill. (Our third child, Corinna, a lawyer, has also worked in and around journalism much of her career.) Still, it’s tricky, bringing children into a clubhouse. The Griffey family discovered that in 1983 when Ken Griffey Sr. brought his two sons to Yankee Stadium. Billy Martin, who had his mood swings, became angry with a small knot of players’ sons romping in the narrow hallways of the old Yankee Stadium and had a staff member tell the boys to vanish. Junior, who was around 13 at the time, never denied his grudge against the Yankees. His Seussian smile when he scored the winning run in the epic 1995 series with the Yankees undoubtedly came from sheer joy, not from old feuds, but still….During his free-agent days, he never entertained offers from the Yankees, even though Billy was long gone. Is baseball a family game? More than it used to be. I don’t recall sons visiting the cramped clubhouse in the old Stadium when Mickey Mantle was conducting replays of his other night games. Clubhouses were often more Rabelaisian than today. Much of that mercifully disappeared after female reporters made their long-deserved arrival and most ball players of normal I.Q. made the major discovery that one large well-placed towel could solve most privacy issues. Plus, the newer clubhouses in New York and elsewhere have inner sanctums where players can shower, and get stuff off their minds. But is it a good idea to have sons -- let’s say sons for the sake of discussion -- wandering around the clubhouse and field all the time during spring training? My feeling is that players do have the right to bond, talk baseball, hash things out, even cuss at each other. And I do mean cuss. In 1980, I brought my 10-year-old son to an exhibition in Bradenton, Fla., home of the champion “we-are-fam-a-lee” Pittsburgh Pirates. My friend Bill Robinson, after his rough Yankee days, was having hard-earned success in his later years. Mary Robinson invited us all over for dinner that night. But before that, Bill invited Dave into the clubhouse, after most of the players had showered and dressed. Dave had been in a clubhouse or two and knew about players. As we sat around Bill’s locker, there was a loud noise from the shower area. Two of the biggest stars – no names mentioned – emerged from the showers, still wet, wearing nothing but very large and shiny bling, not fighting but conducting a philosophical discussion, using words Dave had surely heard before but never in such imaginative pairings and repetition and volume. Bill was a family guy. In his measured voice he said, “Uh, David, maybe you better wait outside.” Times have changed. Clubhouses are larger, more accommodating to a family presence. But as my late friend Bill Robinson knew, sometimes it may also be good for children to wait outside. The latest output from the family is by David Vecsey, who normally spends days and nights editing others but occasionally exercises the writing part of the brain.

David made a journalistic foray into the heart of darkness known as sports fantasy gambling. He emerged with his shirt still on his back, plus a story describing mood swings based on the doings of athletes, some previously unknown until he drafted them. His article on Gothamist: http://gothamist.com/2015/11/30/daily_fantasy_sports.php Then there is my wife’s cousin, Paul Grundy, MD and MPH, IBM's Global Director of Healthcare Transformation. He and two colleagues have written an entry-level primer on the mysteries of health care including trends toward industrial-size health complexes, concierge doctors and the vanishing of the actual family doctor. (You noticed.) The book is: Lost and Found: A Consumer’s Guide to Healthcare by Peter B. Anderson, Paul H. Grundy, MD, and Bud Ramey (contributor). Next is Laura Vecsey, former sports columnist and political columnist, currently covering the U.S. women’s soccer team, World Cup champs, on their victory tour of America, for Fox. Her latest article on Carli Lloyd’s candidacy for player-of-the-year: http://www.foxsports.com/soccer/story/carli-lloyd-and-jill-ellis-have-chance-to-make-more-history-for-uswnt-113015. The family legal wing is in Pennsylvania, where Corinna V. Wilson is the energy behind the consulting firm Wilson500. Corinna helped write the Pennsylvania right-to-know act of 2008, and she flexes her writing skills when that important law is threatened by nervous politicians: http://pafoic.org/2015/02/commonwealth-court-decision-in-psea-case-eviscerates-right-to-know-law/ Finally, my book that has done the most good for others has been revived. I helped Bob Welch write “Five O’Clock Comes Early: A Young Man’s Battle With Alcoholism,” first published in 1982 soon after Bob’s return from a rehab center, to be a star pitcher for more than a decade. My friend Bob passed in 2014 – a lot of us are still reeling from it – but his book, updated, is a handbook for anybody, particularly the young who cannot believe they are powerless over addiction. I’ve heard from people who say Bob's book helped save a life. The new e-book version is from Open Road Media: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/five-oclock-comes-early-bob-welch/1120190861#productInfoTabs Fortunately, some of us also have visual talents. Marianne Vecsey is a painter (above) and Anjali takes photos with her smartphone (below) Uncle Harold is cooking duck, because Barbara always loved it for Thanksgiving.

Since it is Maine, three families have invited him over on Thursday but he wants to be alone, with Barbara, he says. They were together for more than six decades until she died last December. Someone is bringing dessert, and I am sure they will stay a while. Thanksgiving is for remembering people. My mother-in-law, Mary, who passed early this year, always set a great table and made superb pies the kids still talk about. I am sure that on Thursday a few of the older grand-daughters will talk about visiting my father in his bedroom on Thanksgiving evening in 1984, and how Pop surveyed the anxiety on their faces and said, “What is this, a death watch?” He passed a few hours later. The Band played its Last Waltz on Thanksgiving of 1976. We still have the music, and the Scorsese movie, and thanks for that, rocking in my earphones. Thanksgiving is also for people who are with us. The other day I wished a waiter from Central America “Buen Dia del Pavo” – Happy Turkey Day. He said, “Lo mejor” -- the best. I give thanks for the higher power who is there for me, for my wife and our children and their children, and for so many friends from Jamaica High and my student-athlete buddies from Hofstra and my writer pals from the round table, thankful that we still meet, and for the people who protect us, including the good man who has gone gray in six years of a brutal job. And while I am saying thanks, I include the correspondents who enlighten the Comments on my little therapy web site. Every click is part of a community I value.. Thank you. Harold Grundy moved around a lot. Building things.

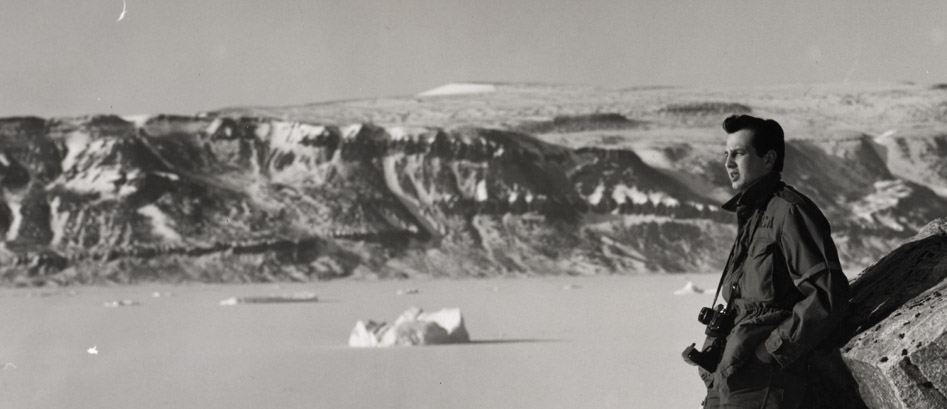

His family knew he went to Greenland and Africa and Guantanamo Bay and other places around the world. Now 93, Harold Grundy -- my wife’s uncle – is being honored with an exhibition of 193 of his photos, “Cold War in a Cold Climate,” at Bowdoin College. Raised in the tradition of the Rogerene Quakers of Eastern Connecticut, the eight Grundy siblings did not smoke or drink and ate mostly farm food; five are still alive, 89 to 96.\ During World War Two, Harold joined the merchant marines, loading ammunition during four Pacific invasions and three typhoons with 90-foot waves. His sector of the convoy was called Coffin Corner. When he came home to Maine, Harold supervised construction and maintenance in some of the hot spots in the world. He spent several years at the base at Greenland where radar was pointed directly at the Soviet Union. There was a 1,000-foot tower he had to climb periodically to make sure it was safe. Later he spent time at Guantanamo Bay, supervising a desalinization plant for the American enclave, and lived in Pennsylvania, supervising the shield for the nuclear plant at Three Mile Island. We have family near there; don’t worry, he said; he made sure the concrete exceeded standards. * * * My wife and I recently drove up to Bath, Maine, where Uncle Harold is mourning his lovely wife Barbara, his companion for seven decades, who passed last Dec. 14. Barbara lived much of her life on the same street where she was born, within view of the Kennebec River. Harold came to Bath for a construction job in 1941, dredging a 50-foot channel so new destroyers could glide down to the ocean. Barbara suffered from childhood diabetes and degenerative arthritis but she always worked, and sometimes traveled with Harold to exotic places. She had every joint replaced in time, but they would take off on a two-month drive to the west coast and back – half gypsies, half homebodies. Their only child, Roger, was shot up flying a helicopter in Vietnam, came home and died in a car wreck a few months later. Several of Roger’s friends act as surrogate sons. One of the friends is Eric Johnson, whose father, Sam Johnson, ran the Chicago Bridge and Iron company, dispatching Harold around the globe to solve construction emergencies. Sam Johnson paid for Barbara’s operations over the years. In their retirement, Harold and Barbara started a woodworking shop, just for fun. Later they turned the business over to Eric, who produces thousands of wooden items. (Anybody with a work bench will have trouble resisting the on-line catalogue.) In her final years, Barbara helped Harold put together a booklet of his career and their travels.. After she passed, he asked Bowdoin in nearby Brunswick if it was interested in the Greenland photos; the curators at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum eagerly accepted, putting them on display in Hubbard Hall on the beautiful campus. Much of the family attended a reception on Sept. 19. Among those attending was Harold’s very accomplished nephew Paul Grundy, M.D., another world traveler who is IBM's Global Director of Healthcare Transformation. Paul said his dad, Elwin, registered as a conscientious objector early in the war and was used in a starvation project that caused many of his teeth to fall out. We got to Maine in October and Harold gave us a tour of the exhibit -- stories about the Eskimos who had rights to visit the base, how the Americans, who lived six to a hut, arranged hoods around their heads so they would not freeze outdoors. He remembered the perils of landing near an Arctic mountain; the rare home leaves. Once the radar went down for a few weeks but two other posts readjusted their signals to keep track of the Soviets. We drove up the coast to visit Aunt Peggy Sukeforth (an in-law of the great Clyde Sukeforth) ; saw the sign Morris Povich (yes, that Povich family) on a clothing store in downtown Bath; saw the three shifts at the Bath Iron Works, still pointing ships toward the sea. Harold told us stories about the four Pacific Landings, how a buddy sneaked him on a reconnaissance flight at Iwo Jima. Once he delivered a car to General MacArthur, who shook his hand. Once in London he and a pal went sight-seeing at 10 Downing Street; Winston Churchill happened to arrive, waving the V-for-victory sign and shaking the hands of the two Yanks. Omce a young senator from Massachusetts sat next to Harold in a Boston train station; John F. Kennedy confided he was planning to run for President. Harold has been interviewed for several documentaries, including one by Ken Burns. On our last evening in Bath, Uncle Harold served us lobster chowder he had made, making sure I had doubles, with crackers. The chowder was wonderful, almost as wonderful as the modest stories of his glorious American life. Just the other day, we were driving on one of those old roads in Queens when I spotted Kissena Park.

“My father used to take me rowing there,” I said. My father could not swim but once in a great while he would take his oldest child to the modest lake in the park. Also, just the other day, one of our children was clicking in a Stanley Cup game, but scrolled past “The Third Man” – the zither music, Orson Welles smirking in the shadows. “My father and mother took me when I was 10," I said. It is one of my great memories of childhood, being judged mature enough to handle the villainy and mystery and politics of that epic movie. The hockey could wait; we pretty much stayed with "The Third Man" right through the final scene in the cemetery. My parents taught me to spot the creep factor in Nixon and McCarthy. They taught me the calling of journalism. My father went off to work six or seven days a week to feed our family. I also knew that he liked working. As busy as he was, sometimes he found time to park near the railroad main line to watch trains racing toward the city, installing in me the chill of the outward bound. Sometimes on a Saturday we parked by LaGuardia Airport and watched the airplanes and listened to Army or Notre Dame football games on the car radio. He also took me to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, and made sure I rooted for a team with Dixie Walker and the next year with Jackie Robinson. He taught me to root for the good guys. He drove me out to inspect the college I would attend. He had never gone, but made sure I did. I know this: I never thanked him enough. (My mother-in-law passed recently at the age of ninety-three. Her grand-daughter, Corinna V. Wilson, composed an obituary, from fond memories.)

By Corinna V. Wilson On February 1, my grandmother, Mary Mase, passed away. She lived many years in Levittown and Shelter Island NY; Bloomsburg and Camp Hill, PA, and Leesburg, FL. Mary Betsy Grundy was born on April 3, 1921 in Ledyard, Connecticut. She and her twin brother Elwin were the second and third of eight children born to Betsy Crouch and Harold Grundy. Harold had emigrated from England as a young man while Betsy’s family had been in the United States since 1633, when Noah Whipple landed in the colony of Massachusetts. One of my grandmother’s ancestors, Stephen Hopkins, signed the Declaration of Independence on behalf of the new state of Rhode Island. Life on the Grundy farm was not easy, and Mary told stories of selling apples door-to-door during the Depression and of the kids going without shoes in the summer to save money. To survive, Harold got a job on the railroad, Betsy opened a bakery in New Haven, and the family operated a boarding house in Orange. Later, they moved to a farm in Waterbury, where Mary met her future and former husband, George Graham. Mary always said that the invention of double-knit was the greatest thing because she had ironed all of the laundry for her big family and their boarders and really didn’t want to iron ever again. To the end, Mary was also a tremendous baker and could teach anyone how to make the perfect pie crust. The Grundys were religious people, and Mary’s deep faith in God sustained her throughout her entire life. She often spoke of talking with Jesus directly and of his multiple interventions in her life. Mary was preceded in death by only two of her siblings – her twin and her baby brother, Tommy. Donald, Harold, Pearl, Bettina, and Lila all survive her and are still formidable in their own right. Mary was also predeceased by her son, Edward Mase. Her remaining four children, Marianne (my mother), George Lauren (Larry), Peter, and Rachel survive. Mary has 16 grandchildren and 14 great grandchildren. Mary married her second husband, our “Grampa,” Richard Mase, in 1947. After his death in 1988, Mary remarried two more times, to Ariel Eisenhauer and Marlin Reisinger. Still attractive to the end, Mary received a marriage proposal when she was just shy of 90, which she declined, despite the amused teasing of her grandchildren that she could be like the Pittsburgh Steelers and have “one for the thumb.” Mary’s long life had many chapters. She was a jewelry model and worked in a munitions plant in Groton during World War II, an original “Rosie the Riveter.” She was an accomplished seamstress and quilter. She made the best gravy of anyone, ever, and her pin always matched her blouse. She taught her grandchildren how to clam the sandbars of Long Island and she prided herself on being a homemaker and a perfect size 6. Ninety three years is a long time to live and our family is going to have to adjust to her absence. (We are thankful to Corinna for expressing what we feel.) Kathleen McElroy used to be the deputy sports editor at the Times. She was calm and smart and knew her sports, including the one called foo’ball. She is, after all, from Texas.

She was running our Olympic bureau in Atlanta in 1996 when the bomb went off after midnight, and she took charge, dispatching us into the darkness and the confusion. Later she moved up at the Times, editing the Sunday and Monday editions. She was the duty officer when the Columbia exploded in 2003. Somewhere along the line, she became part of our family, either my third sister or my third daughter -- not that she lacks for family, with sisters galore and the memory of Lucinda and George McElroy, both formidable. Kathleen’s middle initial is O. Not everybody knows that it stands for Oveta, as in Oveta Culp Hobby, who operated the Houston Post for decades – and under whose leadership George McElroy became the Post’s first African-American columnist. We always figured Kathleen was one of those out-of-towners who arrive in New York, scout out the restaurants and shops, discover a nice apartment, and stay forever. They are some of the best New Yorkers. But foo’ball may have been a tipoff. She is a Southwestern person. Kathleen chose to leave the Times, earning a scholarship to the University of Texas. This fall she defended her dissertation -- "Somewhere Between 'Us' and 'Them' -- Black Columnists and Their Role in Shaping Racial Discourse" -- and received her Ph. D. She is now teaching journalism at Oklahoma State University, with emphasis on the African-American experience. The other day Kathleen sent me a text message that said, “I want to make a difference.” We miss her at family gatherings, and expeditions around the city for the perfect barbecue or the perfect curry. She will make a difference. Every name has a story, and our daughter Corinna tells hers in a lovely May Day essay today.

http://www.wilson500.com/uncategorized/my-name-day-and-the-value-of-a-good-affordable-education/ She tells the story on the day when she witnessed her friend Jacky Nkubito become an American citizen in DC. The name happened as Corinna tells it. I was taking a course on the Cavalier Poets with Dr. Ruth Stauffer at Hofstra College in the spring of 1960, the last semester of my very good liberal arts education. I loved the urgency of Andrew Marvell: Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. It’s possible I might even have used those words, or at least felt the sentiment, in that beautiful flowering spring. I also loved the poem Corinna’s Going a-Maying by Robert Herrick, which our daughter describes so nicely. So how did we name our two other children? Marianne and I agree that her mom, still with us at 93, loved the name Laura. Also, Marianne and I both knew the David Raksin song “Laura,” from the noir movie of the same name, from 1944. Laura is the face in the misty light Footsteps that you hear down the hall The laugh that floats on a summer night That you can never quite recall. One version is by Frank Sinatra -- long before his ring-a-ding-ding stage, I hasten to add. It's a little lush, but a time piece. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7uXPeBRt1fM I was sold as soon as the name Laura was proposed for our oldest daughter. And she’s not the only Laura named for the song. In the comments portion of the youtube Sinatra version, LauraLaVitaEBella says her grandfather gave her the name. Bravo, Nonno. How did we arrive at David for our third child? Marianne notes that I wanted to name him Dylan. It would have been perfect. She counter-proposed David – for the Michelangelo statue in Florence. Many years later, I came to understand King David through the Leonard Cohen song, written in 1984, now one of the great touchstones of contemporary life. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/12/how-leonard-cohens-hallelujah-became-everybodys-hallelujah/265900/ Personally, I am partial to the k.d. lang version on her glorious Canadian tribute, Hymns of the 49th Parallel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0UHv7mDG4s So I say, Hallelujah for music and poetry and art. Hallelujah for May Day. And Hallelujah for Citizen Jacky in DC today. Our aunt died on Easter Sunday, at 96.

When she was in her early 80’s, Angela would take a couple of buses through Queens, all kinds of weather, to visit my mom at home, in the hospital, in the nursing home. Technically, she was not our aunt but a vibrant young woman from central Pennsylvania who married into the clan which is like family to us. “She and Mom called each other ‘forever friends,’” my sister Janet said the other day. Angela came into our lives right after the war, when she and Joe McGuinness were courting. For a time, she stayed at our house, going to work every weekday at the home base of Horn & Hardart – the Automat, where patrons dropped nickels into a slot to buy lunch. She worked in the office, and escorted me into the kitchen to watch the workers fill the shelves with sandwiches and pies. One time she and Joe took me to Radio City Music Hall for a Doris Day movie and the stage show. I still remember the Rockettes dancing to the song, “Red Silk Stockings and Green Perfume,” which came out in 1947. They were young, and handsome, and in love, and it was very cool to be with them. She and Joe settled in Queens, raising three children of their own, but always had time for the five of us. Each of us has stories about their kindness, their advice, how they were there for us. In the past decade, Angela went to live with her daughter, Kathleen, in Oklahoma. My brothers and sisters who visited her in the nursing home out there described her tootling down the hall in a powered wheelchair, about to run a meeting on current events, still the life of the party, almost until the end. I can hear my siblings asking, “Whom can we call now?” Nobody likes getting a call at three in the morning. Too many bad options.

I heard my cell phone rattling on the nightstand, the night before Thanksgiving. My wife was next to me, but the question remained: What? It’s one of those old clamshell phones. (I cannot figure out Mr. Jobs’ gizmos.) I clawed it open. The message was a photograph of a flower in the frost. It was from Grandchild 3/5. Given the size of this great land of ours, I don’t see 3/5 that often. A message is welcome. I pecked out a response: Where? She has a much faster keyboard than I do. Discovery Park, she replied. You have a good eye, I typed. Thanks, Pop. By now I was actually awake. She had outlasted everybody in her household, residents and visitors, and besides, she is something of a night owl. I thought I would toss out a subtle reminder of the situation. You know it’s 3 AM here. This did not seem to faze her. Yeah, she replied. It’s 12 o’clock here. I liked her style. It reminded me of six years ago when I received a call around 4:30 in the morning from Sebastian Newbold Coe, Baron Coe, CH KBE, the great runner who was head of the London Olympic Committee for 2012. Lord Coe had come into the office bright and early and asked his assistant to get me on the phone, which she did. He had a lot on his mind. He was abashed, but we conducted business, no problem, and when we finally met in Beijing in 2008, he apologized again. I thought it was very cool to be able to joke with a lord about an early wake-up call. Grandchild 3/5 did not apologize. Time zones or not, she can text me any time. Plus, she has a good eye. My father worked on Thanksgiving and Christmas and other holidays. I felt sad at seeing him head to the subway in mid-afternoon, but we knew the call of the newspaper business.

He had to leave home and head for the office – breaking news, banter, coffee and snacks from somewhere, familiar faces, stories to edit. Over the years I covered a lot of Sunday ball games and Christmas afternoon basketball games at the Garden, although I don’t remember working on Thanksgiving since a few 10 AM high-school football games many years ago. At least twice, I checked into hotels close to midnight on New Year’s Eve, in order to cover a bowl game in Pasadena or Phoenix the next day. But New Year’s Eve is a good holiday to duck. In the immortal words of Marv Albert, I’d like to, but I have a game. Police work on holidays. So do doctors and nurses and orderlies. In New York, the subways run on Christmas, although not in London. Life goes on. Chinese restaurants flourish on Dec. 25, for the annual ritual of Jewish customers. What do Muslim people do on Dec. 25 in the city sometimes referred to as Londonstan? In recent days, I’ve been watching the lists of Good Companies and Evil Companies that differ about working on Thanksgiving. Wal-Mart, which corrupted people to take over a historic valley in Mexico, is making its workers show up. If Wal-Mart is doing it, it must be bad. I’ve come to the conclusion that there is no good reason for forcing – forcing – workers to show up Thanksgiving evening to herd shoppers, who presumably are there on their own volition. I suggest there is something healthy in a day of rest, even on somebody else’s Sabbath. And Thanksgiving in the United States should be a day of indulging and shouting at the tube and appreciating the people who cook and the people who scrub turkey grease off the pots. Then, at least there could be fitful sleep, working off the calories, before joining the lines on Black Friday. Why do they call it Black Friday? I did it once. Bought a huge television set. It was still bleak and nasty when I emerged from the Best Buy. The experience felt like a frolic, but once was enough. A few miles away, a worker got trampled. This year I read that Best Buy is opening on Thanksgiving Evening to fulfill the stockholders’ dream of a third vacation home. They need it, bless their hearts. I’m proposing some kind of law -- state national, unofficial -- to insure just a few hours of shutdown here and there. Otherwise, we’re all just hamsters on the wheel. I would make this exception – some occupations are essential; others contain a mystique. I’ve come to think my father liked going to work in the late afternoon. Here’s one list of Good Companies and Evil Companies: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2013/11/22/1255378/-Which-stores-are-open-and-which-are-closed-on-Thanksgiving The grand tradition of Chinese food on Dec. 25: http://www.thejewishweek.com/special-sections/literary-guides/we-eat-chinese-christmas Apparently, some pubs open in London, but not the Underground: http://www.londontown.com/London/Christmas-Day-and-Boxing-Day Here’s a list of Black Friday stampedes: http://www.ranker.com/pics/L304743/13-most-brutal-black-friday-injuries-and-deaths James Agee is back, with a revived version of the work he did with Walker Evans in the American South during the Depression. His ear supplied the words and Evans’ eye supplied the photographs of stoic people trying to survive. Here is another great collaboration I seek out at Father’s Day: Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Samuel Barber’s adaptation of Agee, sung by Eleanor Steber at a concert in Carnegie Hall on Oct. 10, 1958. The song works for Mother’s Day but even more for Father’s Day, because the lyricism and discordance suggest what is coming soon. Agee’s father died in 1916, which was commemorated in Agee’s A Death in the Family, published in 1957, two years after Agee’s death. The song describes Agee’s family sitting outdoors, in a time before air conditioning and television. It begins: It has become that time of evening when people sit on their porches, rocking gently and talking gently and watching the street and the standing up into their sphere of possession of the trees, of birds' hung havens, hangars. People go by; things go by. A horse, drawing a buggy…. I heard it first on WQXR-FM years ago, and bought the CD, Eleanor Steber in Concert, 1956-58. I later read that Steber was from Wheeling, West Virginia, and wondered if she would have felt any affinity for Knoxville, further down the Appalachian range. The song reminds me of summer evenings in the 1940’s, when my family stayed outdoors, in our own back yard in the borough of Queens, to catch some slight breeze. I remember fireflies and the Brooklyn Dodgers on the radio and my brothers and sisters and my parents. This is where I usually lose it: All my people are larger bodies than mine...with voices gentle and meaningless like the voices of sleeping birds. One is an artist, he is living at home. One is a musician, she is living at home. One is my mother who is good to me. One is my father who is good to me. By some chance, here they are, all on this earth… When I play this song, I think of our parents, talking about books and politics and the old days, suggesting what is possible for us in our lives. For those of us who know that our parents were good to us, this is a memory. For others, it may be an ideal, a hope. * * * The concert above is from 1948, when the work made its debut. The pianist is Edwin Biltcliffe. Jane Redmont’s web site has a wise tribute to the song, and includes the lyrics: http://actsofhope.blogspot.com/2008/02/knoxville-summer-1915-james-agee-samuel.html My childhood friend Alan Spiegel wrote a lovely biography and critique of Agee in 1998: http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&&url=/journals/american_literature/v071/71.4maine.html Our children and grandchildren will be around. .

My best to all the friends who check in on this little site. Happy holidays. Be well. GV Robbie Parker, the father of Emilie Parker, put on a suit and tie and addressed the public on Saturday.

He was in visible grief, of course, but for a moment his face relaxed as he recalled their brief encounter Friday morning. He has been teaching his daughter Portuguese – he did not say why -- and at six she went for it enough that she and her dad could conduct a conversation. Good morning. How are you? -- the ritual between a parent and a child, perhaps for a purpose, or just the fun of sharing one of the world’s more beautiful languages. “I gave her a kiss,” he said, “and I was out the door.” When Robbie Parker went out the door Friday morning, all was right between them. They had that language in common. As Graham Nash wrote in the song, Teach Your Children: “So just look at them and sigh and know they love you.” We need more than words. We need the connections, the daily acts, the time, the reminders, the bonds that say, “Eu te amo,” before we go out the door. When I took the no-brainer buyout last December, I talked about watching the wheels go round and round. Instead, I’m watching waves.

Two years ago my wife bought me another perfect present, an inflatable kayak from Sea Eagle. Pumps up with a pedal in 10 minutes. Seats two. All I need is company up front. This week Grandchild No. 5/5 and I paddled across the bay to inspect a mcmansion at West Egg. We glided through a school of baby blues (you should see them jump when they are fully grown in September, I told her), and watched a gent in a motorboat cut his engine politely when he reached the No Wake sign. I pointed out the Bronx and New Rochelle past the north end of the bay and we talked about the Huguenots who settled there. We watched the afternoon flights heading toward JFK. After an hour, I told her to navigate toward the dock and the beach. The kayak deflated and was easily stuffed in the back of the car. The summer is young. Several younger friends of mine have lost their fathers recently. What I tell them is, it never goes away. My father has been gone for over a quarter of a century and I still feel the impulse to pick up the phone.

Very often, it is about baseball. Every time Frank Francisco is teetering in the ninth inning, I feel like calling my father, who never heard of Frank Francisco, and blurting in morbid tones, “He’s going to give up a grand slam right now.” Of course, in this new age, my son sends me text messages like, “What are they doing?” My dad would have loved text messages. He was a newspaper guy, would have loved brevity, learned to edit copy on a computer in his late 60’s. I still can’t perform that intricate task and have great admiration for his picking up a new skill at that age. The other thing is politics. I grew up hearing my father emitting a growl about McCarthy or Nixon. I’d love to hear him whenever Mitt Romney says something oily. But the thing I miss the most about my father is his knowledge. He dropped out of high school at 15, but knew so much about books, movies, politics, sports and history. He taught me to love New York City – the ethnic enclave on the Brooklyn-Queens border where he lived as a kid, which other people (not him) pronounced Greenpernt. I have no interest in ever leaving New York because of the drives and subway rides we took when I was a little kid. A war bond rally at Ebbets Field around 1944. The Automats. News stands. He was always on my side, on all five of his kids’ sides. I realize that more all the time. Wish I could ask him about the Hungarian politician (whose name I am forgetting) who visited his neighborhood right after World War One, or the first game ever at Yankee Stadium in 1923. My dad played hooky, at 13 so he could attend. I never did slow down and ask him about that day. Wish I could call him. It never goes away. Or your Jewish bubbe. Or your Italian nonna.

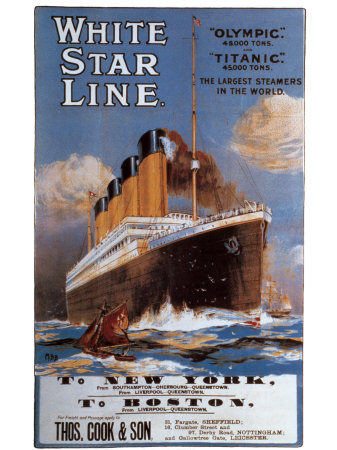

And don’t just listen. Ask questions, Get them to talk. This lesson was reinforced for me recently in a column about Christine C. Quinn’s grandmother, a passenger who survived the Titanic. As it happens, I also had an Irish grandmother with strong connections to the same White Star line that owned the Titanic. I am angry with my youthful self for not asking questions of my grandmother, or at least observing. Quinn was better at it. Quinn is the speaker of the New York City Council and a front-runner for mayor in 2013. As the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic approached, Quinn told Jim Dwyer of The New York Times how her elderly grandmother almost never talked about how she managed to get out of steerage and into a lifeboat on that terrible evening. Dwyer’s lovely column is included here: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/06/nyregion/christine-quinn-retraces-grandmothers-trip-on-titanic.html. Quinn said she knows a little about her grandmother’s adventure because she had the opportunity to ask questions when she was 13. “The only time we spoke about the Titanic was when she was recovering from a broken hip, and I asked her the story when we were hanging around her room,” Quinn told Dwyer. Now that I am a grandparent, I wish I had asked questions of my Irish grandmother, who mostly lived with us until she died when I was 12. I had plenty of time to observe her and ask questions, but, unlike Christine Quinn, I failed miserably. I can remember my grandmother as an old lady in a black dress, who took me, the oldest of five, to church, to the diner for breakfast, and a few times to the movies. I can see her visiting her old-lady friends on Adirondack chairs at Lake George in upstate New York. In my mind, they are all dressed in black, interchangeable. But I cannot even remember her voice – I think she had long since lost any Irish accent -- and I cannot remember her ever speaking about being Irish. If Bing Crosby would sing an Irish ballad on the radio about “strangers” who tried to impose their rule on the Irish, there was no response from my grandmother. Nana had long since become Anglicized and Americanized. And I never asked her – and she never told me, as far as I remember – how she got from County Waterford to the New York area. It involved a circuitous trip that I cannot piece together. I do know that my grandmother’s sister moved to Brussels and lived through two ruinous world wars, but my grandmother took a different path. And it also involved the White Star Line. When my mother was fading in her late 80’s, she mentioned that her mother had worked in South America as a governess, but by that time she could not supply any details. I know my grandmother spoke French from her frequent visits to her sister at Rue Sans Souci in Brussels. Did my grandmother also speak some Spanish? Did she work on the White Star Line to gain passage from England to South America? How did she meet the Australian-born ship’s officer whom she would marry, as they settled in Southampton? All gone now. My mother could remember being in Southampton in May of 1915 at the age of 4, and going down to the harbor as people grieved for family and friends who were lost on the Lusitania. The Titanic was part of her life, through her father. And after the war, the officer’s family immigrated in style on the White Star Line and ultimately settled in upstate New York with a large home and a nearby farm. I’ve asked my younger sister, Janet, who was the “pet” of my grandmother, if she could remember anything about Nana, but she was too young to take in those kinds of details. We all agree, we were not the kind to sit around and tell stories of the old days. I try to tell family history to our grandchildren, but the opportunities are rare. One of my grandchildren, the youngest, actually uses the old-fashioned implement of email to ask me questions about trips I take, and what I do. She shows promise. I am respectful and a trifle jealous that Christine Quinn had the sense to ask questions of her grandmother. I would urge everybody to do the same. _ The holiday mail brought photographs — American backdrops, Indian faces, in their late teens and early 20s. And in one card, news of a baby.

My wife refers to herself as The Stork because she used to fly with children, from Delhi or Mumbai, through taxing layovers in Europe, onward to American airports, to be greeted by family reunions. She would make her deliveries, then hop the next flight home, her stork work done. Marianne estimates that she escorted 30 children on 13 trips, sometimes with a companion, sometimes solo. Many of the families send photos and news — musical instruments, sports, graduations, weddings — and now a baby. The children, mostly girls, had been left in bus stations or on the steps of police stations, had been placed in orphanages, given the best treatment possible, offered first to Indian couples, and also treasured by Norwegian families, American families. We heard about the Indian children through Holt International of Eugene, Ore., which cares for children all over the world. Our contact, our friend, Susan Soonkeum Cox, arranged for me to visit a center outside Seoul, during the 1988 Olympics, to visit a man we’ve been supporting for decades, since he was a child. Susan later asked if I’d be interested in volunteering as an escort, and I said I thought my wife would be good at that. Marianne was more than good. Not only did she love India from her first minute, but she also became involved with an orphanage in Pune, sometimes called the Oxford of the East. She watched the skilled officials and workers, and sometimes jumped in where she thought she was needed, learning from Lata Joshi and other friends and officials there. One judge was balking at allowing adoptions because of rumors that children were used as servants in America. Somehow Marianne got an appointment with the judge and displayed her photo album of healthy smiling children, in the bosom of America. The judge, to his credit, got the point. The orphanage needed a new building. Somehow Marianne convinced a farmer to make some land available for a new building, which is now in use. She could operate in India because she loved the people — Hindu and Muslim, Parsi and Jain, all the castes. She was invited to wealthy homes for lavish meals and shared modest lunches at women’s shelters in the slums. And always at the end, an armful of children, meticulously approved by Indian and American authorities. Stork time. I don’t know how she did it, carrying multiples of children from a year old to 8-9-10 years old, with bathroom issues, food issues, language issues, children who knew they were going to a new home, but first having to go through customs, waiting rooms, cramped airplane seats, the faces of strangers. Marianne's aunt Bettina knew some flight attendants on that great airline, Pan-Am, until its lamentable collapse at the end of 1991; many of them moved over to Delta. They sometimes upgraded Marianne to business class, where she cajoled German or Scottish or American businessmen to hold a crying child while she changed another baby’s diaper. Once she was forced to stay overnight at a Heathrow motel, with an infant and a 7-year-old. When they went down for the buffet in the morning, the older child could not believe there was that much food in the world. She sampled, she ate, she laughed out loud at her fortune. I went with Marianne once, on a trip that began with missions to Thailand and Vietnam. Seeing India through Marianne’s eyes was an adventure. She had the cadence and she had the words and she had the body language. She was home. Our trip back was from Mumbai through Frankfurt to JFK. I was given a healthy boy of 2 or so; we bonded in minutes, doing guy stuff — he grabbed my beard, I elbowed him gently, we wolfed down our meals, I nicknamed him Bruiser and was more than a little sorry he already had a family waiting for him in the Midwest. A French seeker, in a robe and sandals, coming back from an ashram, spelled me at times on the first leg. Marianne’s child had a high fever. The Pan-Am attendants upgraded them, helped ice him down and keep him hydrated. On landing in New York in the middle of the night we rushed him to the hospital, where a medical SWAT team jumped in — discovering an ear infection. A few days later, he was with his new family out west. He’s in college now. On Marianne’s last run to her beloved Pune, she and our older daughter, Laura, brought home one more child — our grand-daughter Anjali. But first there was a farewell ceremony with our friend Mrs. Joshi. The boy in the red outfit in the photo, snuggling up with Marianne? I asked her about him the other day. Oh, she said, he was deaf. Whenever she was in Pune, she always had a child in her arms. I’ve never found a way to tell the story of Marianne’s love of the children, her love of India. She should write a book about her 13 trips, but she says she’s an artist, not a writer. The holiday card, the news of a baby, brought it all home. The Stork is a grandmother now. As Christmas Eve approaches, I think about my Aunt Irene.

She was blonde and bubbly, what the show-business columnists of the day called a “chantoozie,” singing in clubs on the East Side of Manhattan, when there was still quite a Mitteleuropa presence in that neighborhood. Irene worked late, slept late, and was always about nine hours behind the rest of us. “I do remember going with Mom and Dad to a Hungarian restaurant in Manhattan, where Irene did stand up and sing a song to the accompaniment of a violin player,” my kid brother Chris recalls. “She had such a big voice, full of flashy highlights and vibrato, and she gestured dramatically with her hands.” That was Irene. At this time of year, she would hum snippets of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” around the house, but she launched into high gear only on the afternoon before Christmas. My family would crowd into Grandma’s modest row house in the Jamaica section of Queens, every inch covered with ornate decorations. Grandma would serve us sweets, maybe even a sip of Tokay wine for the adults, and we would wait for Irene, who had embarked in late afternoon, heading to Gertz or Macy’s in the hub of Jamaica. Finally there would be a bustle in the narrow hallway, and Irene would burst into the crowded living room, tossing her fur coat in a corner and distributing packages, exquisitely wrapped, for all of us. The packages had just been wrapped by exhausted clerks, eager to go home to their own holidays, and now we were tearing into them, barely half an hour later. I cannot remember what gifts she gave us, only that they were elaborate and expensive. She must have spent every dime she had made for months of singing in some smoky club. Irene is long gone. I regret that I never saw her perform, but when I hear the strains of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” I know I caught the best of Aunt Irene, in her own sparkling living room. |

Categories

All

|