|

When we were privileged to visit Cuba in 1991 for the Pan-American Games, a couple of state translators knew our country, its culture, its movies.

Ziomara and Tessie spoke English as well as we did, although they had never left the island. They called Merrell Noden “Robert Redford” not only for his handsome face,I think, but for something good inside him, something they sensed, from Redford’s movies and his persona. It was a compliment to him, maybe even to us. I hung out with Merrell and Alex Wolff from Sports Illus- trated, a couple of Princeton guys. Somebody else griped about the food one day and one of them, can’t remember which, dryly noted that Cubans had one egg a week while we were eating protein every meal. I slowly realized that Merrell’s love of track and field came from his own running ability at Princeton and later at Oxford. He never told me about his high grades, his love of Shakespeare, but he did brag on his wife, the artist, Eva Mantell, whom I got to meet back in New York. I wish I had kept in better contact as they moved from the city to Princeton, to raise their children, Miranda and Sam. I picked up SI the other day and discovered that Merrell, the strapping athlete, had died of cancer at 59. His friend and colleague, Richard O’Brien, delivered the eulogy, reproduced on Jack McCallum’s web site. It is definitely worth getting to know him better. http://www.jackmccallum.net/2015/06/05/a-friend-remembers-a-friend-both-friends-of-mine/#.VYLHTflViko The Rev. Gardner C. Taylor was 96 and in retirement in North Carolina. Once he was a giant in the pulpit of Brooklyn, the entire world. He was an intellectual who made bells ring when he spoke.

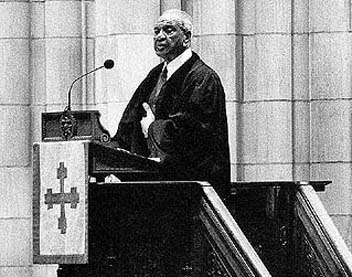

I was just thinking about Dr. Taylor Sunday afternoon as I pondered the closeness of Passover and Easter this year, remembering seders at the Kelman household on West End Avenue and the sermon by Dr. Taylor in Harlem during Holy Week. How lucky to be part of so many worlds. To my chagrin, I had never heard of Dr. Taylor until 1978, when I was covering religion for the Times, although he was a pillar of religion and civil rights (if one can separate them) as pastor at the Concord Baptist Church of Christ in Bedford-Stuyvesant. I heard about a gathering of black pastors every Monday, when one preached and later they all went out for lunch, uptown. It was the day after Palm Sunday, and Dr. Taylor was preaching to the committed, about the ordeal of Jesus Christ during Holy Week. For a time, he was intellectual, measured, logical, but then he raised the amps. I described the mood in the church: “I say to every Christian, You have not even wrestled with temptation the way Jesus did. Where are the blood marks? What pain have you undertaken in the name of Jesus? What sacrifice...? We cannot even know the misery of our Lord.” Then, with most people leaning forward eagerly, Mr. Taylor retold a basic truth of Christianity – that Jesus came back on Easter morning. “He won!” Mr. Taylor exclaimed, and his own colleagues began chanting at the end of every sentence. “He won!” until he finished with the urgent, emotional message of the Resurrection, and ended abruptly. I can still hear his voice pealing. Later I came to know how he and the Rev. Martin Luther King had formed a progressive black Baptist denomination to advance civil rights, and in 1993 Dr. Taylor preached during the inauguration of President Clinton. I grieved from afar in 1995 when Dr. Taylor’s wife, Laura Scott Taylor, the unsalaried principal of the church elementary school, was killed by a truck as she crossed a street in Crown Heights. (He later remarried.) He was a great American, graduate of the School of Theology, Oberlin College , and lecturer at Princeton. He was on my mind the afternoon he passed. For a public figure compared to Hamlet or some of the major saints, Mario Cuomo had a fiendish side.

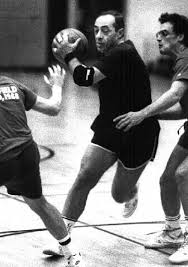

I once reminded him the way basketball players of St. Monica’s parish in South Jamaica, Queens, used to take advantage of two tile pillars smack in the middle of the court. While Sunday Mass was being held on the main floor, the Leprechauns or the Shannons would usher in new victims to the basement. Joe Austin, Cuomo’s coach for life, taught his players to run the old pick-and-roll play on the valid theory that a tile pillar cannot be whistled for setting a moving pick. When Cuomo was governor – a huge source of pride for those of us who grew up around Jamaica – I reminded him how unsuspecting visitors got our brains bashed in. His laugh was long and villainous, from deep in the chest, as he mirthfully remembered suckers decked out on the floor of the rec hall. That was fun, he said. The man had articulate empathy for the poor, the marginal, of his home state, of his nation, of the entire world, but strangers in the basement of St. Monica’s – tough luck, man. From what I heard, he carried this rugged ethic to the basketball games in Albany during his long tenure as governor. In 1993, he told Kevin Sack of the Times: “I'm the most formidable figure on the court because I own the league.” He added, “They all work for me and I am notoriously ungrateful to people who make me look bad.” He was proud of being a jock, a minor-league outfielder until he was beaned in the pre-helmet days. He reveled in the ringer names he used in the amateur leagues -- Glendie LaDuke or Matt Denty or Lava Labretta (because he was ''always hot,” the governor of New York once told me. Cuomo had a long memory, good and bad. For his inaugurations, he invited his gremlin mentor, Joe Austin, who ran a great baseball program on the field of Jamaica High School, when he wasn’t working the night shift at the Piels brewery. Cuomo would address remarks to “Coach,” and when Austin passed, Cuomo made sure that a street and park near the old Jamaica field were named for him. We had a minor connection to the Cuomos – somebody in our extended family became a friend of theirs when the family moved into the twisting back streets of Holliswood. Matilda Cuomo visited our house once, a lovely lady, and my parents voted at the same hall as the Cuomos. The governor spoke well of our relative -- even when she became a hard-core Palinite. He was a beacon to those of us who learned our lessons well in central Queens – that Jamaica Estates and Hillcrest are inextricably linked to South Jamaica and Hollis, that we are in this together. He brokered a housing agreement in Forest Hills when it seemed impossible. Maybe reason and compassion would work elsewhere. In July of 1984, my wife and I were sitting in an outdoor restaurant in Santa Barbara, listening to a couple of stockbroker types at the next table discussing the Democratic convention up the coast, where Mario Cuomo had delivered his epic speech. The two money guys told each other that Reagan would sweep the 1984 election, but that Cuomo was now the favorite for 1988. And they were Republicans. It never happened. Mario and Matilda Cuomo remained New Yorkers, perhaps a regional taste. He had wielded his elbows on the court, and maybe that kept him from needing to wield his elbows for the presidency. Long before he was a doctor, famed as a diagnostician, Kenneth Ewing was the captain of the Guatemala national soccer team. That made him a double legend in my eyes.

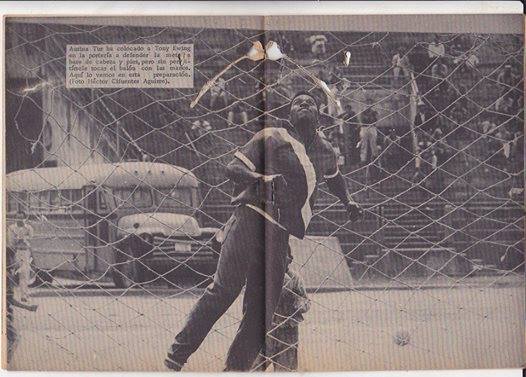

Dr. Ewing passed on Sept. 1, leaving a lot of us bereft. At the crowded wake on Saturday, people traded stories about voicing vague discomfort and how Ewing discovered the underlying problem. The guestbook from the funeral home tells about his talent for saving lives. http://www.fairchildsons.com/view-condolences/?obit=6014 His was an old-fashioned practice, in a big old house near the bay in Port Washington, Long Island, attracting the olla podrida, the grand mix, of our town – old ladies he greeted courteously, commuter types, a track coach and former Olympian (I could only imagine the dialogue between those two) plus the new hopeful generation from Central America. It was an eclectic clubhouse, teammates drawn by the charismatic and talented star, who would poke his head through the door and summon his patients. I was “Professor.” Another guy was Flaco – Skinny. I started going to him when my doctor, a very good friend of mine, was away a lot on business. I asked Dr. Ewing about soccer, and he told me he had played for Guatemala and then professionally in Toluca, Mexico, to finance medical school, and then moved to the United States. He told about a friendly match in Guatemala with the touring Real Madrid stars, Ferenc Puskas and Alfredo Di Stefano. “Another world,” he said admiringly. “Those guys could do things you never saw before.” He told about playing in front of hostile crowds in El Salvador or Honduras, never quite qualifying for the World Cup. Known as Tony Ewing back then (his middle name was Anthony), he was admired for his soccer, and for his second career. In 1989, Guatemala was playing the USA in New Britain, Conn. Dr. Ewing was going up with some countrymen in a chartered van and I was covering the match. He had told me about another Guatemala legend, the old equipment man, from back in the day. An hour before the match, I spotted a little old man lugging jugs of water toward the Guatemala bench. He looked to be 100 years old. I introduced myself and asked if he knew Kenneth Ewing. “Conoce Ewing?” he asked with awe. You know Ewing? “Es mi doctor,” I said. He’s my doctor. I told him how popular Ewing was in my town. Then I watched the old man step proudly toward the field. Later, I wrote this: : http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/18/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-soccer-fan-with-two-teams.html Ewing was as formidable in his practice, specializing in cardiology, as he must have been as a defender. He liked to be in charge. I learned early on that the worst possible thing I could do was raise a medical point: “Hey, I was reading on the Internet…” His response was as terse as a hip check to a marauding forward: “You think I’m trying to kill you?” I knew a patient he had flat-out fired because he didn’t follow orders. I’ve never seen him so furious as when I neglected the blatant symptoms of shingles while I was in California covering the World Series. I came home with a rampaging case of Bell’s Palsy right up my facial nerve toward my eye. He took 30 seconds to totally ream me out, then picked up the phone and had me in a neurologist’s office within an hour, and I escaped visible damage, probably by minutes. For the next six months, he shook his head at me in disdain. A checkup could take a while. He was one of those doctors who work with their hands, getting up close, making sure the system is in working order. At the same time, he would be talking about a Mexico match on television the night before. He insisted he could drive out the Expressway on Sunday morning to fields where teenagers and adults had moves never seen on the US national team. I am sure the US federation would love to find the next Maradona on Long Island, or anywhere, but I knew my place and rarely argued with him. He was a private man but I learned his son Paul (PK) is an Annapolis graduate and Marine major, now retired. His wife Pauline was a teacher. He comes from a family of pro-fessionals, scattered around the world. I once inquired about the name Ewing and he said, “What, you think there weren’t slaves in Guatemala?” Last February I was about to pick Germany to win the World Cup. I went in for a checkup and asked the doctor who would win. Germany, he said. Brazil was too fragile. In journalism we call this a second opinion. Kenneth Ewing was a god to many of his patients, and also to his colleagues. One orthopedist told me with visible relief how he had spotted my mother's problem before Ewing saw her. It was pretty clear Dr. Ewing was not well in recent years, but I never asked. This June I was scheduled to plug my World Cup book at the local library, and I invited Dr. Ewing to join me. I wanted people in town to know him not only as a famed doctor but also as an athlete who had once played with Puskas and Di Stefano, a neighbor who had gone to four World Cups as a fan. Somebody who knew him warned me there was no chance in the world the doctor could make it at 7 PM because he needed to go home and rest every evening, but there he was, sprightly and charming, up for the big game. I went to see him in the hospital a couple of weeks ago. One Guatemalan family, thriving in their second home, had driven up from New Orleans, to bring him familiar food. A nurse had come over from St. Francis Hospital, his home base, bringing home-made bread he loved. The doctor and I chatted for 15 minutes, but only about soccer. Captains must show no weakness. As I left, he praised me for looking in good shape. “I’ve got a good doctor,” I said. Sometimes a person is revealed in the chords as well as the relationships.

There was a memorial for Joe McGinniss in New York on Friday, two months after he passed at the age of 71. Friends and family told their stories, revealing a man of vastly eclectic interests and ties. Roger Ailes, the brains behind Fox, told of a warm friendship that went back to 1968, when McGinniss, a kid of 26, wrote “The Selling of the President.” They did not fight over politics, Ailes said. They just enjoyed each other’s company. Others of the liberal persuasion told how McGinniss could write about Ted Kennedy or Sarah Palin with equal tenacity. And Ray Hudson, the garrulous English soccer broadcaster, who does La Liga of Spain, popped in from south Florida to talk about his friend, who maintained he was actually Italian despite a name and a face that insisted he was surely not. The four McGinniss children were very sweet with their memories and emotions. And one of the best stories came from Joe’s lawyer, Dennis Holohan, who told of not being able to even speak of his military service in Vietnam for 20 years afterward. McGinniss had been one of the great American journalists like David Halberstam and Gloria Emerson and Mike McGrady who went there and exposed the mission for the tragic fraud it was. Finally, Joe cajoled Holohan into joining Joe on a trip to modern Vietnam. They took different routes from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City/Saigon, and the lawyer arrived first, taking a taxi tour of a war museum and then a Buddhist temple, where he totally lost it. Meltdown. But his driver consoled him, saying the Vietnamese people had moved on. You’re a good man, Minh said. I can tell. You need to get past it. When McGinniss caught up with Holohan in Saigon, the lawyer told his friend what had happened at the temple with the taxi driver. McGinniss said he knew it would happen. That was why he proposed the trip. The friend is still stunned that his friend could anticipate such a breakthrough. I never met Joe McGinniss but we became email pals two decades ago, united by our love of Italian calcio and Roberto Baggio and the language and the daily pace of Italian life. I am never jealous of other people’s talent or success or dedication or great ideas but I was tanto geloso of the time he spent in a hill town, and the book he wrote about a scandal among minor-league players he knew. I got to know Joe McGinniss better from the music his family selected for the memorial:

And at the end, there was a slide show of Joe McGinniss’ life, frolicking with his children, out and about in the world, thoroughly engaged, enjoying himself immensely. The background music was:

That’s how I got to know somebody I never met. Addio, buon amico. The scariest thing I ever saw on a basketball court was the maniacal grin of Art Heyman, 10 feet above the floor, as he wielded a pair of scissors.

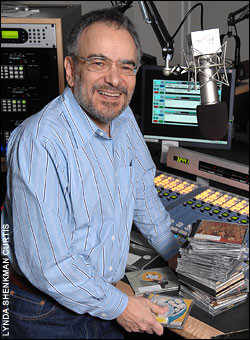

He was cutting his segment of the net after Oceanside High won the 1959 Nassau County tournament; I stopped taking notes to make sure he got down off the ladder without inadvertently doing harm to anybody, in his zeal. Life was always an adventure with Heyman, during a game or during conversation. You never knew wherethings were going. Artie died two weeks ago at the age of 71 in Florida. He would come and go in life, as he did in his mercurial pro basketball career, which consisted of six seasons, two leagues, and eight hitches with seven different teams, plus a few paper transactions with teams that decided they could not use him. He had so much talent coming along as a big-beamed 6-foot, 5-inch star at Oceanside and Duke that it was reasonable to envision him as the next big thing to Oscar Robertson. In fact, the award he won as the best college player of 1962-63 is now called the Oscar Robertson Trophy. Heyman must have had Robertson on the brain. When he was at Duke he used to take little sojourns to the Carolina coast, bringing along a lady friend and registering as Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Robertson. Once he was arrested because the girl was under 18. He was not without his flaws, which he knew as well as anybody. I found him interesting but then again I didn’t have to coach him, as Frank Januszewski did at Oceanside or Vic Bubas did at Duke. He could taunt opponents, take a punch at somebody for no reason, and toss elbows in practice, just out of meanness. He was big enough to insinuate himself toward the basket, like Robertson, and when the Knicks drafted him first in 1963-64, he scored an average of 13.4 points in 75 games – what turned out to be the best season of his career. The next year he was sitting a lot after Harry Gallatin, the rugged old forward, was brought back from the Midwest to coach the new breed. This really happened: I was with the Knicks in a hotel lobby in Providence, when one of the players, rolling his eyes, informed us that crazy Artie had been playing poker after a loss to the Celtics earlier in the night, and Gallatin walked by the open door and, in a gesture of friendship, asked if he could take part. “If you won’t let me into your game, Coach, I won’t let you into mine,” Artie said, and meant it. The next season he was at Cincinnati, and after that he was in the American Basketball Association. He had a bad back; the attitude was not so good, either. One year Heyman was playing for the New Jersey Americans, the forerunners of the new Brooklyn Nets. That is to say, before the Nets had Julius Erving from Roosevelt, L.I., they had Artie Heyman from Oceanside, L.I., a few miles away. After games Artie would beat it back across the George Washington Bridge to the East Side of Manhattan, where he ran a bar that catered to flight attendants and males. His career in the singles-bar trade was as disjointed as his basketball career or his persona. It was hard to keep things straight with him. I would diagnose him as having concentration issues; there was something sad about him, an inner lost child. I ran into him in Manhattan in his various bar cycles, would catch up on the phone when I could track down his number. About 15 years ago I ran into him in North Carolina. He did not look healthy, and he felt under-appreciated. It was a long way from Oceanside High, when he climbed that ladder with the sharp object in his hand and nobody dared turn away. He arrived out of the ozone in the very late ‘60’s, a voice straight off the Fordham campus. On WNEW-FM, a station with its share of edgy types, he came off as much more than sophomoric but not yet a grad student – a perpetual junior, who was starting to get it. That is a compliment.

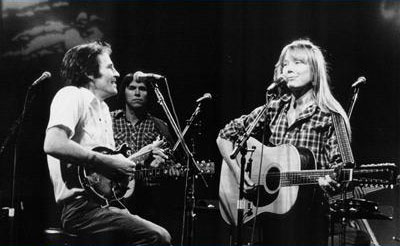

Pete Fornatale maintained that mix of wonder and knowledge as long as he lived, which was not nearly long enough. He died Thursday at the age of 66. He was a friend. We lived about a mile apart in Port Washington for decades, and took long walks around the old sand mines on Hempstead Harbor. We talked about serious issues as we walked – spiritual things, political things. He was deeply affected by 9/11 – talked about it on the air at WFUV-FM, his first and final station. He didn’t seem much interested in talking sports, thank goodness, which gave me the leverage to ask him about his music contacts. There were perks to being a friend of Pete’s. He introduced us to our heroes, Anna and Kate McGarrigle, in some Village basement dressing room, right after a show. We sat with him when he emceed a benefit brunch at the Lone Star, when Richard Manuel and Rick Danko were about to go back on the road. Check out the High on the Hog album. Richard sings She Knows in that sweet falsetto, and at the end Pete and Richard salute each other. Now all three of them are gone, and so is Levon. Pete and I took our sons to a Grateful Dead concert at the Nassau Coliseum. He introduced me to John Platt, his Long Island buddy, now a Sunday-morning presence on WFUV. And one night in a club on the South Shore of Long Island, he introduced us to Christine Lavin, his friend, now my friend. Chris once performed Sensitive New Age Guys live on Pete’s Mixed Bag show – using Pete as the male foil. That night in the club, she called out both of us to sing backup. She’s currently on the road, working on a tribute to Pete that will be played sometime over the weekend on XM radio and also on WFUV-FM on Saturday. We are all in shock. But the best part was the music, the thematic shows, where Pete could find four or five songs that belonged together. (Doug Martin’s obit in the New York Times on Friday does a great job explaining Pete’s technique. ) I hope this doesn’t get Pete in trouble with the authorities – what can they do to him now? – but he used to make copies (cassettes, which dates me) of his best thematic shows. I play them on my walks. One show was Ladies Love the Beatles, amazing arrangements of old favorites. Another show was about aviation, with a sensational version of Tree Top Flyer by Stephen Stills. Afterward, Pete admits, with that heh-heh laugh of his, that the song just might have been about an illegal pursuit. Another cassette was about the Sunday papers, all those sections, including the so-called funnies, with Adam Carroll’s song urging Dagwood to take Blondie up on the roof for a glimpse of the sky. That one certainly puts some zip in the step. Pete was still growing, still learning, still thinking, still talking. My deepest condolences to his family. I’ll miss the walks but I’ve got the cassettes. They played music from deep in the collective continental soul. Four Canadians and a drummer from Arkansas. First time I saw Levon Helm was backstage at the Garden during the Dylan tour in ’74. Somebody had placed a backboard outside The Band’s dressing room, and he was messing around with the ball, between shows. Wish I had said hello, but I was spying on Dylan’s sound check, so I kept moving. Now his family says he is dying of cancer. My favorite song from Levon is Ophelia because it is so….so…southern. Boards on the window/Mail by the door…. Reminds me of funky neighborhoods in the south, where people come and go. Although what could be more southern than Levon’s buzz-saw rasp on The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down? Only met him once. He played Loretta Lynn’s father, Ted Webb, in the movie Coal Miner’s Daughter. I had written the book for Loretta, and the movie people graciously invited me to the openings in Nashville and Louisville. I was afraid the movie-makers might commit a Beverly Hillbillies version about a part of the world I love. But as soon as I saw Levon as the slender, bashful miner, I knew the movie was going to be respectful. The second night, there was a party at the hotel, with Loretta and Sissy Spacek jamming together. Sissy could crack up Loretta by imitating her voice and her down-home bended-knee gestures. Levon was singing backup. It was the women’s show. During a break in the music, my wife sidled up to Levon and told him how good he was in the movie, and then she added, “You can sing, too.” He might have had a bit to drink, but not enough that he couldn’t detect the compliment. “Thank you, ma’am,” he said. “He was so cute,” she recalled on Tuesday, when we heard the awful news. Of course, I'm giving away the punch line.

This was at the 1990 World Cup in Italy, when a bunch of traveling American writers were in Florence to watch Our Lads get waxed. Searching for the press tribune, one of my colleagues spotted a man in a bright blue blazer standing in a portal. What with the blazer, he could have been an usher. "Excuse me," the reporter said, probably in slow, basic English, "but we're looking for the press section." "My name is Giorgio Chinaglia," the man in the bright blue blazer replied with a smile.. "And I believe it is right over there." My friend knew enough to be apologetic. Giorgio, who had what one might call a strong sense of self, thought it was funny. Giorgio knew that current soccer writers might not recognize him. But defenders and keepers (and his own coaches and general managers) would always remember him. Giorgio Chinaglia was one of those headstrong stars who came to New York in athletic middle age and could handle the pressure, much of it self-induced.

Think Reggie Jackson, Keith Hernandez, Mark Messier, Earl (the Pearl) Monroe. Giorgio had the chutzpah to stick his 6-foot-1 frame as close to the goal as he could, and defied anybody – keepers, defenders, referees or, for that matter, his own coaches – to dislodge him. Playing striker for the New York Cosmos from 1976 through 1983, he had the coraggio – translated more as gall or impudence than mere courage – to declare himself responsible for scoring goals. Anything else was somebody else’s job. Just put the ball near the No. 9 on his jersey, and he would do the job. He will always be the career leader in scoring for the North American Soccer League, inasmuch as the league is defunct. Giorgio died at home in Florida on Sunday, at 65, of a heart attack. A friend said he had distress earlier in the week but checked himself out of the hospital. That would be Giorgio. Why should he regard doctors be any differently than he did Hennes Weisweiler, his German coach with the Cosmos, whom he openly defied. “My job is to score goals,'' Chinaglia told me in 1981. “Other players may play both ends of the field, but they don't score as many goals. That is what the game is all about.” And he meant it. Giorgio was the first world-level player I got to know when I was discovering soccer in 1980. He had a vaguely sinister presence even on his own team because he had the ear of ownership, and more or less flaunted it. I saw him score two in a 2-1 victory over the Philadelphia Fury in 1980 – first on a header, and then with a shot out of the pivot with 18 minutes remaining. He faked to his left as if to use his power foot, his right, but then he swerved to his right to score at close range with his left foot. “Usually, he will set up for his right foot,'' keeper Bob Rigby of the Fury said about the second goal. “But you know Giorgio, he is an instinctive player. The great ones don't think. They just do it. He is more dangerous with his back to me because I can't tell what he will do. He has an uncanny sense for what is right. '' Giorgio just didn’t care what people thought. He was born in Tuscany, in Carrara, known for its marble, and in Italy was regarded as something of a straniero, an outsider, because his family had run a restaurant in Wales and he had come up through the pro club in Swansea. He later was a star for Lazio -- by now the tifosi called him Long John, because he was tall, and spoke English. He played for the underperforming national team in 1974, and when he moved to the Cosmos he was criticized by Italian fans for defecting. That was Giorgio. He went his own way. The Cosmos were made for him, the way New York was waiting for Reggie and Hernandez and Messier and Earl the Pearl. Later he did television in Italy and helped run Lazio and sometimes gave striker-like feints that he might be in the mix of leadership if the Cosmos ever truly materialized again. Instead his heart gave out. But never his gall. PS: Some serious soccer buffs might see this. Your own memories/tributes/critiques of Giorgio would be welcome right here: |

Categories

All

|