We were upstate, visiting our daughter. Laura had three tickets for a concert in the park in Saratoga Springs – a group from Chad, now living in Montréal. It was the last night in a Monday summer series -- called On Stage, because the chairs were on the stage of the large outdoor theater, an intimate setting for a few hundred people. Four musicians, known as H’Sao-* -- three Rimtobaye brothers, Caleb (guitar), Mossbass (bass) and Izra L (keyboard), and their childhood friend, Dono Bei Ledjebgue (percussion) -- blended in intricate harmony, went off on solo riffs. We caught bits of French, bits of English, and a lot of their tribal language. The longer they played, the more we realized we were hearing a cri de coeur, a call from the heart – the life of the immigrant, trying to stay alive, seeking less dangerous corners of the world. They have been in Montreal since the turn of the century, but have never left home. One song, “For My Family,” began with drummer Dono Bei, rapping about waiting for a bus in Montreal, at 5 in the morning, reading a postcard from home, a cousin asking him to send him a car. The audience chuckled, but Bei’s piercing voice let us know this was serious business: “You wanna make it happen so badly for your family, “You keep digging, you keep digging.” “I got ten brothers left behind, “Their scholarships are all on me.” The music was beautiful; it came from deep. One of the brothers explained why they had left home – childhood friends were having to choose between Christianity and Islam, with apparently ominous results. Their voices blended: “I do this prayer to whoever’s up there, “Jehova, Jesus, Allah, we need an answer.” At times the group reminded me of the tight, intuitive “Buena Vista Social Club” from Cuba and at times it reminded me of the plaintive voice of Bob Marley cutting through the ozone. I thought I heard some of the South African chords Paul Simon incorporated into “Graceland” and at times I heard Sam Cooke on “A Change Is Gonna Come.” But mostly I heard these four brothers from Chad and Montréal, trying to work it out. The musicians teased us: How do you know you are alive? Somebody in the audience said, “Because we are moving.” Exactly, the musician said. Prove you are alive. Get up and dance. Many people did; Laura stood up, made eye contact with Caleb, the closest to us, letting him know she was very into their music. They wailed, they rapped, they talked about love. They told a tale about a rite of manhood, going into the wilderness to confront a lion. (The band used to be bigger, or so they claimed.) They prodded us to sing a chorus, in their tribal language. One band member chided us: we didn’t know what the words meant, did we. Something not very nice, he suggested. After 90 minutes, on this balmy upstate evening, we were part of the rhythm, part of the harmony, part of the sadness, part of the joy, the front pages of the papers and the news on the television, immigrants drowning, Rohingya being slaughtered, children being ripped from their parents on the U.S. border. After the show, the musicians stayed around, chatting softly, giving hugs. Dono Bei said the band was heading to Montreal in the morning; my wife and I would return to New York a day later. “Bonne retour,” he said. Good return. We bought all three of their CDs and rocked with them all the way down the Northway. When I got back to my laptop, I looked up their site: https://hsao.ca/en/ The group has been discovered by the Canada Council for the Arts, has performed in Canada, the U.S., Europe, Australia and also New Zealand with its rich cultural programs. But they have not been in New York since a visit to Lincoln Center in 2017. I went poking around for a video: the first one that popped up showed them in choir robes, in a cathedral (see below.) Exactly, my wife said. They are immensely spiritual. Messieurs: quand allez-vous jouer à New York?

* -- H'Sao means the Swallow of the Sao, the people who were the ancestors of present-day Chadians. The group's origin is presented in its name: the musicians in H'Sao come from N'Djamena, the Chadian capital, a vast country located between the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. -- www.festivalnuitsdafrique.com/en/artist/h’sao Two continents have essentially been outsiders at the World Cups, going back to 1930 – Asia and Africa. Both continents had reason to celebrate on Tuesday, with Japan beating Colombia, 2-1, in the first match and Senegal beating Poland, 2-1, in the second. Russia steamrollered Egypt, 3-1, in the third.

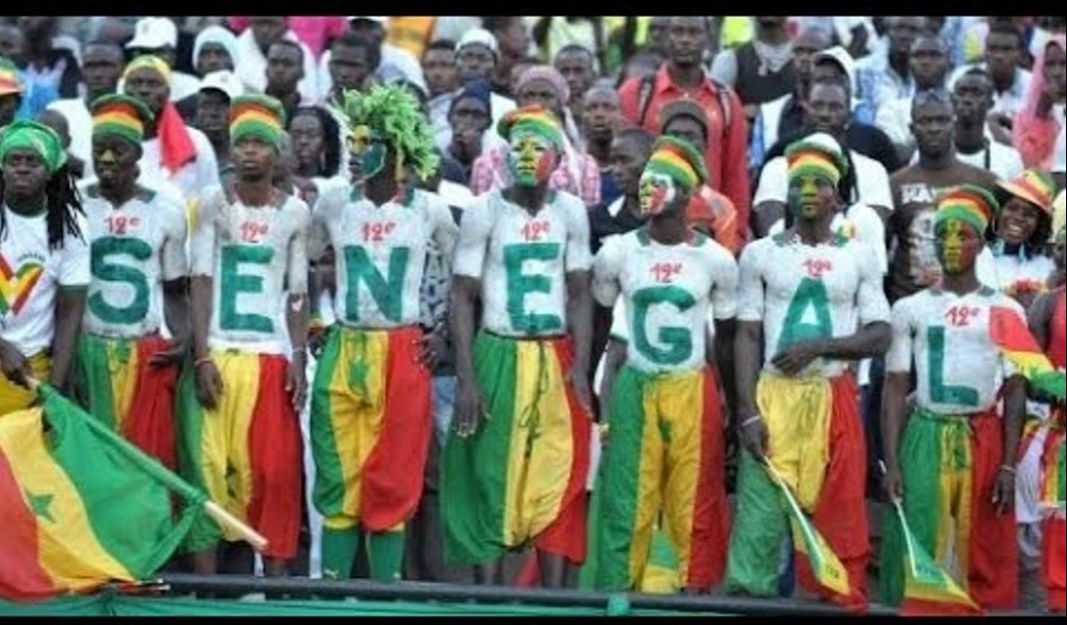

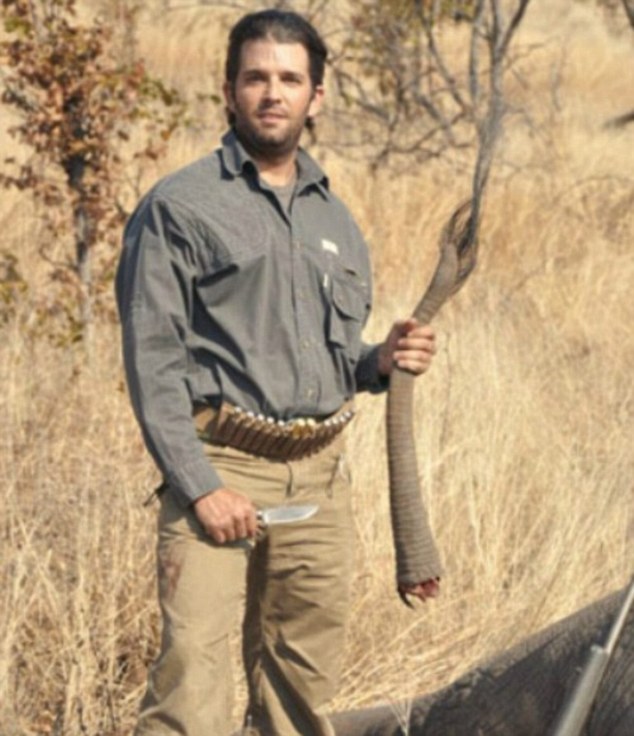

All three matches had defensive breakdowns – a Colombia defender stuck out his arm to block a shot in the first match (bad instinct), a Polish defender was struck by his teammates’ deflection (bad luck) and an Egyptian player ran into a brick wall named Dzyuba and a ball deflected off him (bad choice of brick walls.) I enjoyed seeing Senegal back in the World Cup for the first time since 2002, when it stunned France, the defending champion, in the opening match in Seoul. Fast and powerful, Senegal was hailed in 2002 as the arrival, finally, of Africa as a factor in the World Cup. Then again, we have heard this before – about Nigeria, about Cameroon, about Ghana, about several nations from northern Africa. Who can forget Roger Milla, as ancient as his continent, coming off the bench for Cameroon in Italy in 1990, scoring four goals, and then dancing, each time? I hear reasonable people worry about the nationalistic aspect of the World Cup. My position is, what better reason to chant and cheer for a nation (or an entire continent) than a mere football tournament? Get it out of the system. Plus, nationalism is infectious. One becomes an instant citizen, like me hearing the beautiful anthems of Canada, France, Germany, Russia. On Tuesday, the green-clad Senegalese lined up at midfield for the anthem, called “Pincez Tous vos Koras, Frappez les Balafons.” I looked it up: “koras” (a harp-lute) and “balafons” (a xylophone-type instrument) are native to Senegal, and can be used in the playing of the anthem. The composer was Herbert Pepper and the words were by Senegal’s first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor. The English translation: Everyone strum your koras, strike the balafons. The red lion has roared. The tamer of the savannah Has leapt forward, Dispelling the darkness. Sunlight on our terrors, sunlight on our hope. Stand up, brothers, here is Africa assembled. Fibres of my green heart, Shoulder to shoulder, my more-than-brothers, O Senegalese, arise! Join sea and springs, join steppe and forest! Hail mother Africa, hail mother Africa. I was doubly touched when I spotted the Senegalese manager, Aliou Cissé, who played on that 2002 team that stunned France and reached the knockout round. He (amassed two yellow cards along the way.) Cissé is the only black manager among 32 in this World Cup, and, pecking around on the Web a bit, I cannot find another black leader in previous World Cups. I was also delighted by gents wearing white body paint and tricolor pants and soft caps, with S-E-N-E-G-A-L painted across their chests. I flashed back to waiting in railroad stations in France and Korea, cheered by the sweetness of African fans. However, Africa has not become a power in the World Cup -- merely the supply line for the great leagues of Europe. (These Senegalese players earn their living mostly in England and France.) Cissé worked the sideline sporting dreadlocks and eyeglasses. The Senegalese players ran and jostled, with Ligue 1 and Premiership skills. May their numbers increase. After a long day came the delayed debut of Mohamed Salah of Egypt, recuperating from a shoulder injury. The star of Liverpool scored a late penalty kick, solemnly kissing the ball and the earth and praying to the heavens, Muslim style. His first World Cup match. His first World Cup goal. More to come. But we say that every four years.  Lovely Photo by Stephen W. Oachs Lovely Photo by Stephen W. Oachs (This posting has been revised since the presidential swerve late Friday evening, via Twitter.) https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/17/us/politics/trump-elephant-trophy-ban.html?_r= Ted Turner used to make this impassioned plea for an endangered species -- indeed, for an endangered planet -- during his noble effort, The Goodwill Games in Moscow, 1986. Remember 1986? Remember Goodwill? Remember Gorbachev? For that matter, remember Ted Turner? I dubbed him a “holy fool” because of his Dostoyevskian zeal. John Feinstein, covering those games in Moscow, heard Turner’s stump speech so often that he could sense the punch line coming. “But what about the elephants?” John would squawk. Those were the good old days, when we produced holy fools, not flat-out fools. Now Turner's cause is sabotaged daily by Donald Trump, whose only concern is setting up his own spawn and the Mnuchins and Wilburs of the world for more riches. Trump is all for porous pipelines and spewing coal stacks (and tax revisions) as long as they make somebody richer. For a moment this week he also tried to set up his own killer sons and their type to get richer from slaughtering “trophy” animals in Zimbabwe and importing their parts. In mid-week Trump announced his intention to make it legally possible to import -- to display -- to brag about -- these tails and tusks and Lord knows what else, cut from the dead bodies of these most civilized mammals. The total of worldwide elephants has dropped 30 percent from 2007 to 20014. I read that in the Times. People with the savage name of Trump have contributed to that. Are proud of that. What an ugly family. For some reason, Trump changed his mind in one of his late-night Twitter eruptions Friday, saying he was delaying any action on the (Obama-era) policy to ban importing elephant "trophies." The article in Saturday's paper: _r=www.nytimes.com/2017/11/17/us/politics/trump-elephant-trophy-ban.html?_r= I have felt more personal about elephants since visiting South Africa for the World Cup in 2010. Our guide Witold took four journalists on a day trip out of Johannesburg for the only exposure to nature we would have during a hectic month. Witold was trying to find lions and other Bold Letter animals during our quickie run into the wild. He parked on a dirt road and looked around. Then he saw a family of elephants to our left, moving toward us. We were on their crossroad. He backed up 10 feet, and the family of elders and infants walked slowly in front of us, their heads turned to the right to keep an eye on us, as well they might. (“We’re not Trumps!” I could have said, “We’re not that sort!”) Their right eyes were patient and wise as they walked with dignity. I fell in love with elephants at that moment, the kind of easy emotion for a day-tripper on a day off from football. I wish I had taken photos, but I was mesmerized. That was my lifetime African experience. Big deal. But it stayed with me, to the point that I feel familial rage toward a plunderer who enables murderers from his own sordid brood. Have a tusk, Donald. Have a tail, Eric. Go shoot something, brave guys. “But what about the elephants?” Where is Ted Turner when we really need him? Obscured by other events, “The Circus” recently announced it is going out of business in May.

What circus? To New Yorkers, there is only one – The Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus. The Barnum referred to P.T. Barnum, the showman who once observed there is a sucker born every minute. You still hear that quote these days. Were we suckers, taken to the circus as little kids, and then taking our own little kid, or borrowing somebody else’s kid, to pay homage to lost childhood? The circus said it is shutting down because people stopped going when the circus had to get out of the elephant business. I suspect it was more complicated. Little kids can find more esoteric stuff in whatever phone or computer they are packing. Movies have stuff that explodes (but no plots.) Kids can kill thousands of people with a flick of the thumb on a video game. Elephants? Echh. And young boys don’t need to go to the circus to get a glimpse of a bare thigh or bare shoulder of an exotic-looking acrobat. It’s all out there on the web, and more. In classic Americana lore, the circus was always there for boys who wanted to run away from home. Today, young people don’t run away to join the circus, they…(supply your own punch line.) Still, I’m thinking something is lost. One of the first signs of spring in New York was always the photos in the papers (really, do check out these vintage photos) or TV footage of elephants striding through the Queens Midtown Tunnel, en route from their special trains – cooped out by Shea Stadium, how appropriate -- to the supersized elevators in Madison Square Garden. Better than the first robins. I knew a young hockey writer who told his readers that the Rangers stunk even worse than the elephants in the basement. Great line. Well, except that the circus was still in Norfolk or Charlotte. Henceforth, he was known as the guy who made up elephant shit. But what about the elephants? Another great line. It came from the screeching voice of Ted Turner, mad genius of CNN who created the Goodwill Games, primarily between the U.S. and the soft, vulnerable Soviet Union. In 1986. Ted went to Moscow to pitch environmental sanity. Birds were dying. Fish were dying. Then, Ted would squawk, “But what about the elephants?” (Imagine, a holy fool with a dollop of compassion and knowledge.) Well-meaning people said the circus was cruel to elephants and the supply system endangered the great beasts. I say poachers were more of a danger. No poachers in Sarasota, their winter quarters, or the depths of the Garden. But it’s a good point. Elephants are noble beasts. Some are deities. We have a sweet, wise Ganesh in our home. I was once in a taxi in Mumbai that lingered behind a huge elephant carrying stuff. And on a day off during the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, four soccer writers took a day trip to the Pilanesberg preserve and our guide Witek paused at the edge of a path as a family of elephants passed, watchful eyes right, a few yards in front of us. I have loved elephants even more since then. If shutting down the circus helps that family in that preserve, then closure is a good thing. On May 21, the circus plays its last show a few miles from my home on Long Island. I can’t imagine going. But I reserve the right to feel nostalgic for another time, when we could enjoy elephants (and bare shoulders) in the center of the big city. I associate Roger Cohen with his skateboarding on a small ottoman, at risk of a broken neck, to celebrate a Chelsea goal on the tube.

I associate Tracy Kidder with his long legs racing around the bases on a softball party, decades ago. Yes, serious writers, have their sports side. I just caught up with books by both of them, touching the deepest issues in the world – genocide, inequity, identity. Cohen’s book is “The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family,” published this year by Alfred A, Knopf. It is partially about the imbalance in many members of his family, which has made the trek from Lithuania to South Africa and onward. His mother became troubled shortly after emigrating from South Africa to England early in her marriage and never recovered. The book also delves into what it means to be Jewish in a dangerous world, with some of his family escaping ahead of the murders in Europe, making a success in South Africa, but never feeling quite accepted in England – hearing the discreet lowering of voices and being described as “Jew” rather than “Jewish.” Later Cohen re-settled, for reasons he came to understand. “One day, banking over New York City on the approach to LaGuardia, watching the serried towers of midtown, a single word welled up from deep inside me: home.” Cohen writes of the city of “incomers.” He has become one of journalism’s most staunch defenders of the marginal. Tracy Kidder has also been exploring corners of the world, ranging from the emerging computer society to poverty in Haiti, often seeking people who take chances, who make a difference. His idealism is on display in his 2009 book for Random House, “Strength in What Remains: A Journey of Remembrance and Forgiveness.” Kidder traces the wandering of a people, and an individual, Deogratias Niyizonkiza, a member of the Tutsi tribe in Burundi. Barely escaping a bloodbath while in medical school, Deo survives in Africa the same way some of Cohen’s family survived in Europe – through the grace and courage of others. In Kidder’s book, the man called Deo lands in New York, is helped by a baggage handler named Muhammad, a former nun, and an intellectual couple from Greenwich Village – the parallel layers of strength that work so often in this city. Kidder recreates Deo’s survival in Burundi, and moves toward the present, with Deo, now a poised 40-something New Yorker, running a medical facility back home in Burundi, where the prevailing custom is to not remember terrible things that have happened. My conclusion is that there is no such thing as light summer reading. These books by Cohen and Kidder would make me think and care in any season. The name jumped out of a random paragraph about the horror. A world-renowned poet was caught in the madness in an upscale mall in Nairobi.

I heard about Kofi Awoonor in 1976 when I was covering Long Island for the Times. His friends at the State University at Stony Brook were publicizing his arrest in his homeland of Ghana. He said he had driven a friend in political trouble across the border because that’s what friends do. He had been at Stony Brook before going home, and had many admirers in the States, including two Pulitzer Prize winners, Louis Simpson and Bernard Malamud. Of everything I did on that story, I most remember calling the Ghanaian embassy in Washington, D.C., browbeating some telephone-answerer, saying, “Doesn’t your country know it has imprisoned an important artist, a man the world knows?” Reporters know how to make ourselves obnoxious in cases like this, and I’d like to think I did. Ghana came to its senses in 10 months and released him for time served and assured him that he remained a citizen in good standing. He had dropped from 165 pounds to 135 pounds but said he caught up with his reading in prison. He also got a collection of poems out of his little sabbatical, called The House by the Sea, after the prison where he lived. In January of 1978 he returned to Stony Brook to see his friends, and drink wine, and recite poetry. One he read was dedicated to his daughter Amewsika, whose name means, The Human Being Is More Precious Than Gold. Tomorrow my love You will turn eleven I had promised a party; But worry not, I won’t be there. Your mother will give you a party; Tell me if she doesn’t. Where am I? Well, very near you. But there are iron bars on my door. A man stands there with a gun. He brings me food and water Now and then And I dream that soon You and I and all of us Will be free! Kofi Awoonor lived and wrote and taught from Ghana, and served as a diplomat, for the rest of his life, which ended this week while traveling to Kenya for a literary festival, as a prominent voice of Africa, of humanity. Other men with guns appeared at the mall and slaughtered innocents. I went to a bookshelf – I knew just where it was – and found his book, The Breast of the Earth: A Survey of the History, Culture and Literature of Africa South of the Sahara, which I had read as I prepared to write the two stories while he was imprisoned. At the reception in Stony Brook, he had inscribed the book for me, the only time we met. I want to add that I am grateful to Ghana for giving him back his life, his voice. I have since come to meet Ghanaian soccer fans in Germany and Brooklyn and South Africa, the nicest people. They mingled with Americans at the World Cup in 2010, some carrying flags of both nations. I think of Ghana as Kofi Awoonor’s homeland, and grieve along with the nation. The article from the Sahara Reporters: http://saharareporters.com/news-page/ghanaian-author-kofi-awoonor-killed-kenya |

Categories

All

|