|

"There are 9,388 graves in the cemetery, most of them in the form of white Latin crosses, a handful of them Stars of David commemorating Jewish American service members. As antisemitism rises again in Europe, they seem somehow more conspicuous." ---Roger Cohen, The New York Times. "D-Day at 80" -- June 6, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/06/world/europe/dday-80th-anniversary-veterans-remember.html Marianne Vecsey noticed the same thing, back in the mid-70s, when we drove with our young children to Normandy, in the sweet damp spring. Part of Marianne's ancestry goes back a thousand years to Normandy, but this was not about us. This was about the Allies who died during the invasion, now 80 years ago. We live in New York; we tend to notice stars amidst the crosses. "You hear the number, but when you stand there, and see the graves with crosses and stars, it sinks in. It's stunning, actually," Marianne said on D-Day 2024. Roger Cohen had the same reaction. Of course he did. Roger is one of the greatest Times writers of any generation -- fearless, perceptive, the voice of the underdog, the champion of the fallen. I've spent great times with Roger running around Germany during the 2006 World Cup or watching him suffer for his Chelsea F.C., in some New York pub. I've read his poignant tribute to his mother, to all who suffer, in his 2015 book, "The Girl From Human Street." https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/22/the-girl-from-human-street-review-roger-cohen-memoir-motherodyssey-of-loss I miss him in New York -- Brooklyn, to be specific, but now he is right where he should be, in the middle of it, as Paris Bureau Chief, preparing his masterful text for the 80th "anniversary." Marianne and I and "the kids" made the same pilgrimmage north from Paris, borrowing a friend's chugging sedan, heading toward the tangy air of salt water, toward Mt. St. Michel. (I had learned to love Mt. St. Michel, reading Richard Halliburton in grade school.) Now we were there, in a scruffy little gite near the beaches, in a spring so damp that sheets did not dry on the line. We saw the Bayeux Tapestry, of course we did, and then we headed to the beach. Funny, as we sat atop one of the sandy cliffs, we heard distinct German voices behind us -- three cars, three sporty couples, no longer the enemy, just modern Europeans on spring holiday, to see the Normandy beaches, the landing now three decades in the past. We took in the logistics of that landing, what it was like to be in those landing craft. The only person I knew who had been in one of those boats was Lawrence Peter Berra of St. Louis; but Yogi never talked about it, just as his teammate Ralph Houk barely alluded to his battlefield commission at the Battle of the Bulge. Veterans don't talk much. Marianne learned that when she was a lifeguard at a village pool on Long Island. Some of the older town workers had been in the war, but never shared details. Now it is 80 years, and centenarians will talk, particularly if a master journalist like Roger Cohen asks the right questions, the right way. People talk to Roger. Read his words; look at the photos. Marianne stored the visual memories, the visceral impact, of the Stars and the Crosses. She's an artist -- has a lifetime of paintings out there.

We loved our April in Paris, staying in a sous-sol in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The Metro. The Louvre. The Bois. Then we came home and resumed normal lives, and one night Marianne waited for the family to go to sleep, and she painted her geometric tribute. This month Roger Cohen has been, as always, in the right place, recalling the Canadians, the Europeans, the Americans, who stayed behind, in Normandy. The backdrop looked familiar -- the Jamaica Ave., Elevated train -- The El.

It was the hub when I was a kid. In Sunday's NYT, there is a story about Brandon Blackwell, who broke into the British quiz shows, representing not Oxford, not Cambridge, but London's Imperial College. Great article by David Segal. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/business/uk-university-challenge-brandon-blackwell.html I hope you can access the article. *** Great stuff in the NYT in recent days. Wesley Morris wrote a literate and knowing article about the last show of "Curb Your Enthusiasm," 12 years of aggression and bruised feelings. I will admit, I never watched the show -- mainly because I had the feeling, "Wait, I know those people." I'm from New York, I know people in LA, I've had dealings with people in movies and journalism and just-plain-life. The only series I watched, obsessively, in the recent third of my life was "The Sopranos." I plotted my whole week around a TV set that carried it -- finding a motel on a reclaimed coal strip mine in Eastern Kentucky. I totally understand "Curb" fanatics. Wesley Morris, one of the best writers at the NYT, explains why Larry David annoyed and entertained people with his intrusive stands with friends and strangers. I hope you can access this masterpiece. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/05/magazine/larry-david-curb-your-enthusiasm.html *** Finally, has anybody noticed the reappearances of stars from the NYT sports section before it was disappeared in favor of stuff from a sports website? The stars have found places in the diaspora of former sports bylines, and have been encouraged to write wise and literate articles about sports, the kind readers used to expect: My Queens pal, Andrew Keh, has a piece in Sunday about soccer fans who congregate to a Brooklyn bar whenever their favorite team -- from Denmark -- is playing. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/nyregion/akademisk-boldklub-new-york-owners.html Billy Witz was assigned to write about the Caitlin Clark phenomenon at Iowa, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/02/us/march-madness-women-iowa-lsu.html And Talya Minsberg, a versatile editor and byline in the lamented Sports section, now writes for the Well section -- so naturally she explained the physical and mental training that brought Clark and Iowa to the NCAA finals. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/05/well/live/caitlin-clark-iowa-training.html As we used to say when I was a reporter on the National staff half a century ago, I detect a trend. May I quote Bruce Springsteen in his epic "Atlantic City:" Everything dies, baby, that's a fact But maybe everything that dies some day comes back For decades, they were teammates in the sports pages of that great paper, Newsday.

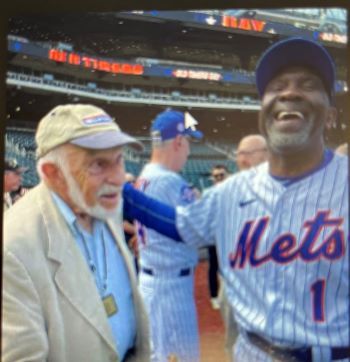

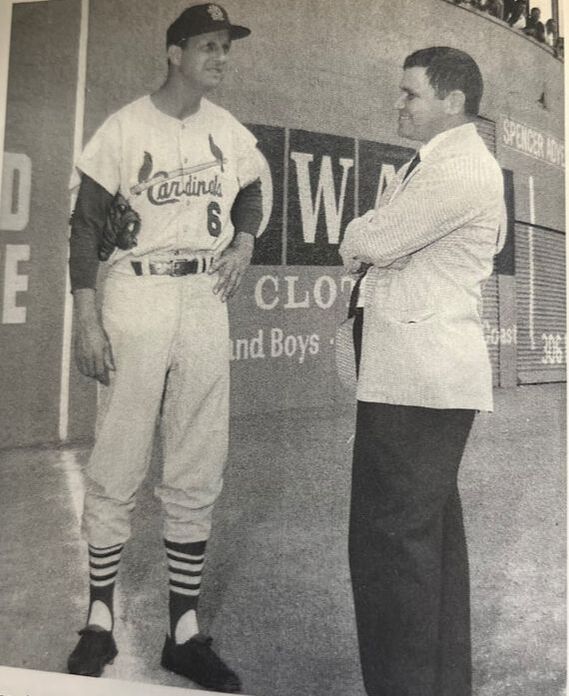

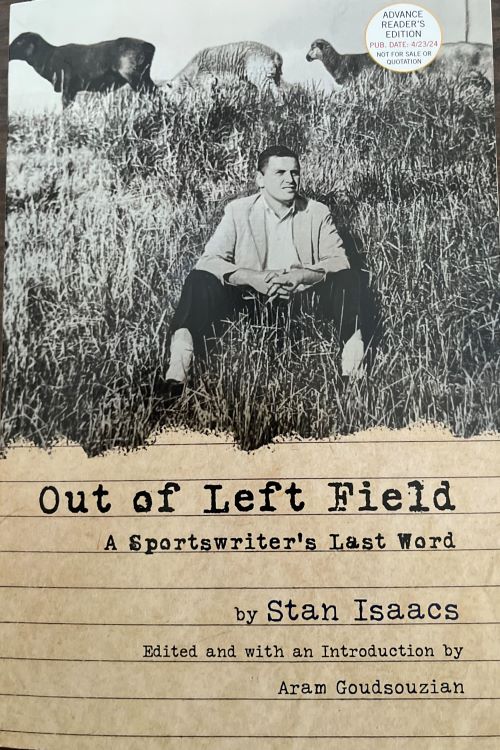

Steve Jacobson could cover anything, and ask probing questions, Stan Isaacs saw life from his natural position – way out, left field. They were my colleagues and my friends and my inspiration when I worked at Newsday in the 60s. We even played touch football together. Stan passed in 2013 but his words are being revived in an autobiography, “Out of Left Field: A Sportswriter’s Last Word,” to be published in April by the University of Illinois Press. Steve is very much with us in a current podcast celebrating a magnificent book he wrote in 2007: ”Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball – and America,” by Lawrence Hill Books. Steve’s book is, alas, out of print at the present time (as Casey Stengel used to say), but just in time for Black History Month, Jacobson -- known as Jake -- has been celebrated in a podcast by Steve Taddei, from his perch in the Bay Area. “I found ‘Carrying Jackie's Torch’ at the public library,” Taddei wrote in an e-mail. “The book fit in well with ‘Leadership Lessons From the Negro Leagues,’ because it gave me perspective to the adversity my heroes of the 1960's and 70's went through and overcame on their journey to the Major Leagues.” It is no secret that the evils of segregation, which kept Black players out of “organized” ball were not magically dispersed by Jackie Robinson’s first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Robinson took the first curses from opposing dugouts, the blatant reluctance of some Brooklyn teammates, and the daily problems of living in a considerably racist nation. And it was still going on when Steve Jacobson was interviewing players in the 60s. One of the most approachable was Jim (Mudcat) Grant, a star pitcher, who one day challenged Steve to expand his questions: talk to other Black players who ran into the walls of segregation. Years later, that’s what Jake did – hearing how Black players at first could not stay in hotels with their white teammates, how they had to eat brown-bag lunches in team buses, how Black players felt underrated by their managers and teammates. Always a dogged reporter, Jake sought out players we knew from our working years --Tommy Davis who always greeted writers from “my hometown” of Brooklyn, Ed Charles, the spiritual center of the 1969 championship Mets, Bob Gibson, the great pitcher who used his hard veneer to keep hitters – and reporters -- at bay, and Dusty Baker, whose winning personality has carried him to an enduring career as manager. Henry Aaron. Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby. In this podcast, Steve Taddei spoke by phone with Jake (and me, a little) and near the end, Anita Jacobson, Jake's wife, tells about the hotel pool in Florida, where the Mets took spring training, circa 1965. The formidable Anita -- who cooks, and teaches cooking-- recalls what she and my wife Marianne did when another white mother pulled her child out of the pool rather than share chlorine water with a Black child. Life was like that for the Black baseball people who carried Jackie’s torch. Steve Jacobson worked hard to get memories of the Black players, and now Taddei has honored what Jacobson did in his book. Here’s the podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/leadership-lessons-from-the-negro-leagues/id1646816110?i=1000644226588 *** And here is the glorious scoop of the day: Stan Isaacs’ words are back in print. In his retirement, Stan was writing his memoirs, but after the crushing death of his vibrant wife, Bobbie, in January of 2012, Stan’s heart was broken, and the book was unfinished when he slipped away 15 months later. Fortunately, Aram Goudsouzian, an editor for the University of Illinois Press, became interested in the genre of sportswriters – starting in the late 50s, in their chattery, irreverent, fearless and informed glory in the 1960’s. The Chipmunks: Stan Isaacs. Larry Merchant of the Philadelphia Daily News and Leonard Shecter of the New York Post and a dozen or more chatterers. “I’ve been working on a book about sportswriters and the big political and cultural shifts of the 1960s, and in the course of my research I read Mitchell Nathanson’s excellent biography, Bouton,” Goudsouzian wrote in an e-mail. “In the notes he had a record of Stan’s unpublished memoir, which I thought might be a good primary source for my own book. So I emailed Nathanson about it, and he put me in touch with Stan’s daughter Ellen, who sent me an electronic copy. As I read it, I had the sense that it should be published – though it needed editing, it had Stan’s distinctive voice and a lens into the shifts of the Chipmunks’ era.” Never having met Stan, Goudsouzian gave the manuscript some nips and tucks, and undoubtedly some enlightened surgery to highlight the inner Isaacs. Stan knew himself as a quirky lefty, coming out of the Depression and the politics of the 1930s, and he tells his best stories in this book. The photo on the cover? One night, covering the Yankees in the old ballpark in Kansas City, Stan chose to watch the game from the hill behind right field, patrolled by a few sheep. Vintage, definitive Stan Isaacs. They were wonderful days -- and I carried them with me to the Times in 1968, blessed with the skills and attitude of Isaacs and Jacobson and the other Chipmunks. I am extremely proud of my career at The Times, but like ball players who have loyalty to more than one ball club, I still refer to both Newsday and the Times as "we." Jacobson’s world, Isaacs’ world, are definitely from another time. Nowadays, young people do not read newspapers…and newspapers die….and even a great paper like The New York Times has chosen to blow up its sports section, with its tradition of reporters and columnists licensed to report and comment. Miraculously, in these hard times for sports sections, Stan Isaacs still patrols left field and Steve Jacobson still carries Jackie’s torch. Together again. The Daily Miracle is waiting every morning at the top of the driveway, courtesy of a diligent delivery lady, who never misses a day.

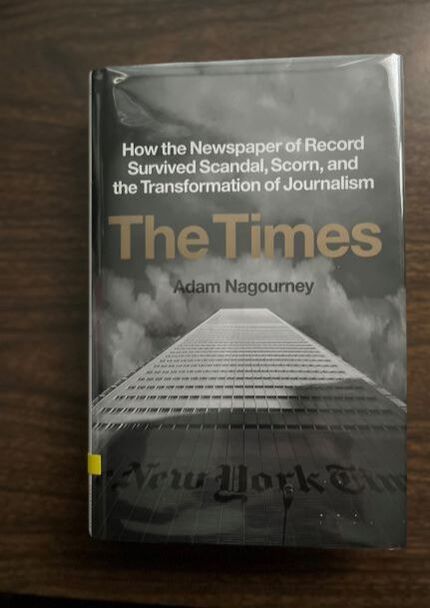

Friend of mine at the New York Times plant in College Point, Queens, calls it “The Daily Miracle,” because it returns every day (with the collaboration of thousands of journalists in Manhattan, in Queens, and all over the world. This bundle in a blue bag is a miracle even though everybody knows young people don’t read newspapers, but there are enough of “us” who want to hold the paper in their hands and flip pages and peruse, peruse, peruse. (The plant also prints 50-odd dailies and weeklies – part of the miracle but also the foresight of the people who run the NYT.) Take this from an octogenarian who must have his fingers on “the paper,” there is another miracle in the journalism world – the ever-changing website of the same New York Times, thousands working around the world in all the continents and all the time zones. As we speak. Nothing like flipping electronic pages in the middle of the day to keep up with the judicial progress against the larcenous and bumptious Trumps. Or waking up and checking what has happened in the Middle East since the cut-throats came across the border to kill and kidnap on Oct. 7. We get the news and the embellishments from a great news-gathering organization (where I used to work), and that is a miracle because it took decades of insight and doubt and trial and error to save the blue-bag Daily Miracle but also to create the alter ego known as nytimes.com. The evolution of newspaper into the journal that never sleeps is documented in a new book, “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism,” written by Adam Nagourney, one of the many great reporters, who is still working there. For 43 years, I knew, I witnessed, I even managed to grumble and whine about the changes being foisted on us. (I do not do change well. I can provide witnesses.) I was around as a news reporter in the ‘70’s, when bulky and balky Harris terminals swallowed entire masterpieces after hours of pecking away at the keyboards, even though we had pushed, poked, whacked the “Save” keys. A living technology pioneer-saint named Howard Angione talked some of us out of our rages. Later there was another saint named Charlie Competello. Meanwhile, our bosses competed in their lairs. Some of them understood the online era at first and some did not. The book goes into Shakespearean length to show the decades of the long knives, over policy, over technology, and over flat-out human emotions. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”—King Henry the Fourth, Part Two, William Shakespeare. Top editors feared the managing editors they had just appointed and even publishers and family had a mix of human strengths and weaknesses. But four decades of friction came and went – and the NYT is in Ukraine and the Middle East and all over the United States. I’m not getting into personalities in this review. I just want to bear witness to the foresight and talent and perseverance of the owners and the editors and the reporters – and the readers. I had the honor of working for national editors Gene Roberts and Dave Jones and the great copy editors on that staff. I remember being assigned to the federal pen in Marion, Ill., where a lifer bank robber had completed his bachelor’s degree in a prison program. I turned in my article and copy editor Tom Wark called me and said, “This is not up to Vecsey standards…could you run this through the machine again?” I tried. The NYT had dozens and dozens of great editors like him. Later I worked for Abe (Rosenthal) and Arthur (Gelb) as a Metro reporter in the 70s. They could forget about you for weeks…but then they could give you an assignment that made you glad to be a journalist. (The end of the Vietnam War, 1973, as seen by cynical veterans in a steamy bar in deepest Queens, my choice of venue.) The computer age was under way when I returned to Sports in the 80s. Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, with his snarky sense of humor, held an occasional lunch meeting with us in Sports. One day I played grumpy-lifer and asked why the NYT needed the color that was starting to appear in the paper. The publisher said, as I recall: “We live in color. We dream in color. The Times needs color.” Look at the great reporting by Amelia Nierenberg and brilliant photos by Hilary Swift on grieving Maine in the past week. Of course, Arthur was right. The book describes how the Times dispatched long-time editor Bernard Gwertzman to bridge the gap between the traditional NYT and the infant Web-era NYT. One day, Gwertzman held a lunch with Sports types ad one of our many great reporters complained about his scoops going on line so early that his good pals on other major papers were poaching his work. Gwertzman was unflappable: “A year from now, we won’t be having this discussion,” he said. He was right. The reporter became a star in the Web age, too. (Recently, the NYT blew up its talented sports section. That decision will undoubtedly be in the next NYT history book.) But for now, Adam Nagourney has given Times readers (and Times lifers) a thorough view of the comings and goings of talented, driven journalists. I am in awe of the lavish meals and copious alcohol consumed by our leaders, often followed by sharp managerial decisions ...placed between career shoulder blades. Nagourney reminds us how long it took for female journalists and gay journalists to get a fair break to use their talents. Good for him. The editors argued and decided and changed courses. But somehow, somehow, The New York Times is better than ever, 24 hours a day. In print. Online. Either way, a daily miracle. ### In his final hours, Grant Wahl wrote that he had been wrong. He had predicted that the Croatian star Luka Modric was too old at 37 to take the team any further, but after Croatia reached the semifinals on Friday, Grant wrote a mea culpa. Then he went on to write about the second World Cup quarterfinal of the day, and he died, at 48. The circumstances must be examined by American authorities. It’s way too easy for Elon Musk’s new toy to carry kneejerk claims that Grant Wahl was given the Khashoggi treatment, some kind of chemical bonesaw. But we don’t know, not yet. The New York Times and other responsible news agencies quickly examined Grant’s own recent articles mentioning his not feeling well in Qatar, and going to a clinic at the stadium, and he described how other journalists covering this marathon had the same symptoms, from long hours and work stress and crowded press rooms and Lord-knows what kind of travelling microbes. I’ve been there, done that, under the same conditions, during World Cups and other mass events. (More on that, below.)  Grant Wahl was one of the major journalists covering soccer, and had been right about so much, including the repressive air to this World Cup in Qatar, born from scandal – packets of $100 bills to delegates -- in the world soccer body, FIFA. One day at the World Cup, Grant wore a rainbow t-shirt, the universal symbol of support for gay rights, gay existence, and he was held by stadium police, until released. That takes courage. Most people learned after Grant’s death that the rainbow t-shirt was a tribute to his brother, Eric, who is gay. His brother linked the death to Grant’s speaking up for gays, and for thousands of itinerant laborers who have died building these pop-up stadiums in a country with enough money to buy FIFA, the most corrupt sports organization in the world. “They just don’t care,” Grant wrote about leaders of Qatar and FIFA. I read Grant’s posts from Qatar, on the personal website he was building after leaving Sports Illustrated during the ongoing pandemic. He was offering his experience and courage for paid subscriptions, but also made some free essays available. He was no home-bound typist – known as an Underwear Guy -- pecking away on a laptop. Grant Wahl was out there, fully credentialed, with the respect of the soccer community, and also with the eyes of the Qatar security force on him. In a very real sense, he was a lone wolf, existing on his own guts, his own instincts, his own strength, in a FIFA/Qatar environment that had no reason to like what he was typing. As soon as I heard about Grant’s death, I had a pang of déjà vu. I was also 48 during the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, a country I love, traveling to modern and hospitable cities, hundreds of miles apart. I stubbornly continued to jog at high altitude, taking in the bad air. After a few weeks, I was shot. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t move. Couldn’t think. Couldn’t type. Fortunately, my wife was with me, to witness that I was running down. I also had something Grant Wahl did not have these days – a home office. I called the NYT sports department and said I was dragging, and needed a day or three off, but my editors, my friends, Joe Vecchione and Lawrie Mifflin, agreed that I had another great assignment, the Goodwill Games in Moscow, coming up, and I needed to be strong for that. My editors told me to come home, see my doctor, and determine if I was strong enough to go back out to Moscow – which I was. One of the best assignments I’ve ever had. (Plus, my wife was with me, buying fresh vegetables and fruit at a farmer’s market in a nearby square.) I also had editors watching my back, whether as a news reporter or a sports columnist. To this day, even as a typist for my own Little Therapy Website, I consider every word, every opinion, from the vantage point of the great editors, who found mistakes, even reined me in sometimes, much as I griped. Journalism has its dangers. I’ve been sent to riots and shootouts and assassinations and coal-mine disasters where I had to be quick on my feet, but nothing like colleagues currently in brave, admirable Ukraine. Sometimes, “even in sports,” the hours, the travel, the diet, the microbes in crowds, can beat you down. We will learn more. What we know now is that Grant Wahl was doing his work, writing so well about a subject he loved, and he has passed, way too young. In the midnight hour on a murky Saturday night in late October of 1986, Shea Stadium was going mad.

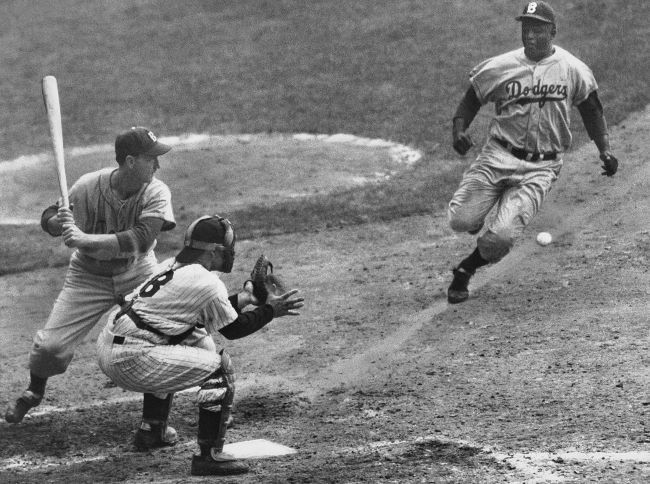

A squiggly grounder by Mookie Wilson had somehow kept the Red Sox from winning the World Series that night – and fans were screaming, and nearly a dozen New York Times writers were pounding away at their laptops, shouting into phones, bustling noisily to update their early stories for the last print deadline of the evening. Enlightened cacophony. The sports editor, Joseph J. Vecchione, sitting behind us in the pressbox, was coordinating with the staff in the office, making dozens of decisions, on the spot. Then it was over. We had gotten it done, on deadline. A young Times news reporter, doing spot duty to cover fan madness, police activity, etc., watched the sportswriters (so often maligned as “the toy department”) do their jobs. When things quieted down, the young reporter said casually to the sports editor, “Wow, that was impressive,” or words to that effect. And Joe Vecchione said drily: “We do it every day.” If Joe had added, “Kid,” he would have sounded just like Clint Eastwood in “The Unforgiven.” That professional pride epitomized Joe Vecchione, my friend and advisor in my early days of writing the sports column. Joe passed Friday evening at 85, after years of suffering from Lewy body disease, cared for by his wife, Elizabeth, a wise and devoted nurse. They are parents of Elissa Vecchione Scott and Andrea Vecchione, with three grandchildren: Joe’s aura of family man was clear to people around him. He was a boss with values. I got to know him as a terse, decisive voice on the phone, in the 70’s, when he was an editor in the photo department, and I was a news reporter. Sometimes I was at breaking news and I had to coordinate with the photo editors. Joe was authoritative and efficient. Then he was plucked by Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Gelb to help form the new SportsMonday section, and he was there in 1980 when sports editor LeAnne Schreiber recruited me to be a reporter, filling in for Red Smith or Dave Anderson here and there. When LeAnne moved on, Joe became sports editor, and when Smith died in 1982, it was Abe Rosenthal’s decision to hire a new columnist, and it turned out to be me. Here is where the kindness and shrewdness of Joe Vecchione took over. I had been conditioned by 10 years as a Times news reporter, to keep any trace of myself out of the copy. Give sources. Quote authorities. No opinions. That was the old, gray NYT – and I was one of the foot soldiers, thoroughly indoctrinated. As a columnist, I knew the subject matter, and could write and report, but I was trying too hard to find a voice, hinting at my opinions. I was being too cute. Joe had some advice (and I paraphrase:) “Be yourself. Tell us what you think. People want to know how you feel, what you know, what is right and wrong. Don’t hold back. This is the way things are going these days. You have freedom.” He removed a decade of thoroughly valid reportorial rules, freeing me up to be a columnist. Joe also had an instinct for hiring and enabling good people, hiring columnists Ira Berkow and Bill Rhoden, relying on deputy editors like Bill Brink and Lawrie Mifflin, and he backed up his columnists. I benefited from this in 1990, when I was writing columns from the World Cup of soccer, held in Italy. The young American team, in its first appearance in 40 years, managed a taut 1-0 loss to the Italian team – a huge accomplishment. But I pointed out that Italy did not have great strikers – that is, players gaited to score goals from up close – and I wrote this was because their great national league imported scorers from Germany and Argentina and Brazil. I wrote: “The home-grown players do not develop the knack of scoring. Mussolini once lamented that his was a nation of waiters. It is not stretching the truth to say that Italy is currently a nation of midfielders.” The next day, the sports department got a call from an Italian-American reader who felt using the remark attributed to Mussolini was prejudicial. (Fact is, I love Italy and root for the Azzurri, except when they play the U.S.) The person in the office, taking the call, told the reader that the sports editor was okay with my comment. And who is the sports editor? “Joseph J. Vecchione.” That pretty much ended the conversation. Joe could be tough, and he had to make a lot of decisions. I once was whining in the office about something or other, and Lawrie Mifflin, the deputy sports editor and loyal friend of Joe’s and mine, told me, in effect, “You have no idea how much he has to handle every day” – including complaints from leagues, teams, player unions, sponsors, agents, public officials, fans, to say nothing of staff members. In Joe’s regime, we let it fly, and Joe fielded the complaints, kept most of it from our ears. Joe was sports editor for a decade, then moved back into the mainstream of the paper. He retired at 65 and the editors promptly brought him back to help the transition to the new building a few blocks away. Over the years, I was impressed by the masthead names, the serious people (some of whom condescended to sports personnel), who were his social friends. They trusted him – for core values, like honesty, like thoughtfulness, like culture. That is no small statement about a Times official, my friend, who helped move the sports department into the future. (Any insights/anecdotes about Joe? Please add them in Comments, below.) Omigosh, Mike was there! That was my reaction while electronically poking around online files and saw this angle of Jackie Robinson sliding toward Yogi Berra in the 1955 World Series. The umpire ruled Robinson had stolen home, but to the end of his days, Yogi would levitate loudly, to dispute that call. But I’m not writing about baseball today. I’m writing about photographers like my late friend Meyer (Mike) Liebowitz, who passed in 1976 but lives forever in the stock of photos, now being included in a digitizing project by the Times. (That project was described in a two-page spread in Sunday's Metropolitan section. See link below.) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/books/reading-around-new-york.html In the dozens of times Mike and I worked together on news – not sports – stories on Long Island, he never once mentioned that he was one of the photographers arrayed around Yankee Stadium that epic day. (John Rooney of the AP caught the slide/tag that, to this day, proves nothing.) Mike Liebowitz one of dozen photographers I got to know – and admire – on our assignments together. This digital project reminds me that one of the under-described relationships in journalism is somebody with a pad and somebody with a camera, going on assignment, watching each other’s back. I was in my mid-30s and Mike was surely twice my age when we were paired by the random needs of the Photo Desk, Sometimes I would be in his car because it held his equipment. Once we were chasing a politician allegedly visiting an estate in Nassau County’s gold coast. Down a long driveway, we knocked on a door and were told to take a hike, so Mike backed out the driveway – and we nearly got T-boned by a speeding car. Another time we were doing something way out on the North Fork (a project to save the fading potato farms?) on a glorious early October day, and Mike was driving along an untended beach and the tide was high, so I asked Mike if he had 20 minutes to spare, which he did, so I stripped down to my skivvies and dove into the warm, placid waters, and then we proceeded due west. In that two-page spread in the Times’ Sunday metropolitan section, there are 12 vintage photos about reading in public. What touched me was that I worked with just about all the photographers – Jim Wilson, Keith Meyers, Marilyn K. Yee, Fred R. Conrad, Andrea Mohin, Chester Higgins, Jr., and William E. Sauro, who did a lot of sports. And that doesn’t include other Times pioneers like Michelle Agins (who one Christmas Eve popped over to my family dinner and took a treasured photo of four generations) and Sarah Krulwich, who has become an institution with her photos of everything Broadway. Or dapper little Ernest Sisto, who worked on the field back in the day of bulky Graflex cameras, and would get a discreet signal from his compagno Phil Rizzuto when the Scooter was about to drop a bunt. And then there are my two pals from the 1994 Winter Olympics in Norway – Paul Burnett, who took photos of the presumed winner, Nancy Kerrigan, and Barton Silverman, who was snapping Oksana Baiul, who went later. Barton was – and I am sure still is – a force of nature. He got roughed up covering the 1968 Democrat convention in Chicago, and in 1996 he was nearly arrested in Atlanta for trespassing in the new Olympic park in downtown Atlanta. (I tried to warn him.)

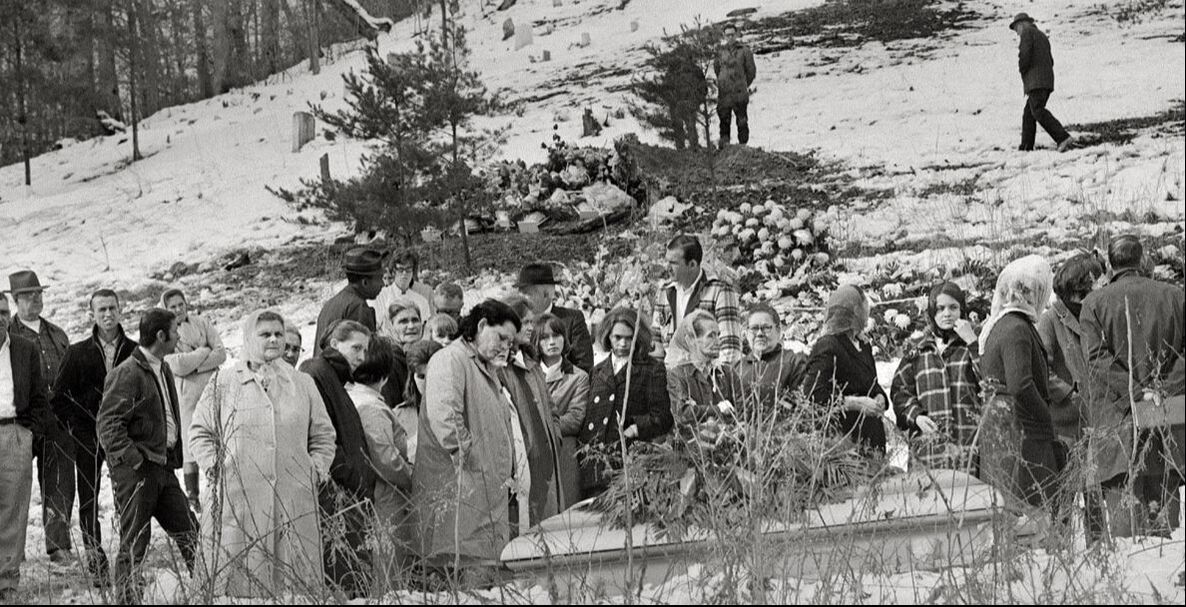

I know I am omitting a dozen or two Times photographers, but I want to discuss another facet – free-lance photographers. I don’t know what it is like now, but when I was a news reporter based in Louisville, the Times used great photographers from the Courier-Journal in their spare time (my late friend Ford Reid, for one), and also a free-lancer named Kenneth Murray, a true son of Appalachia from the Tri-Cities area where Virginia and Tennessee meet.

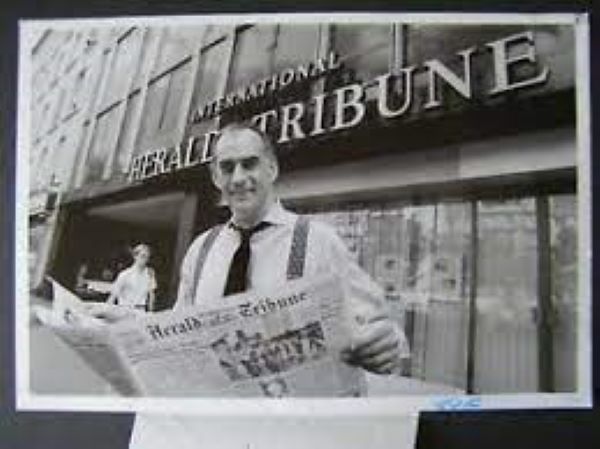

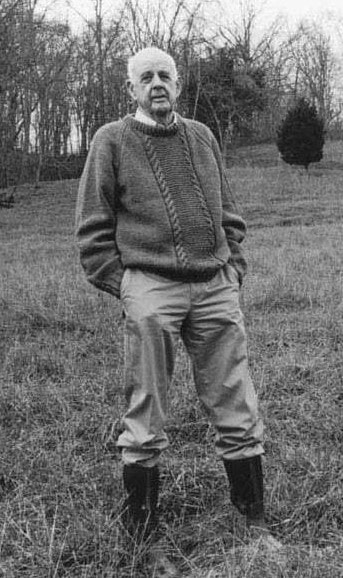

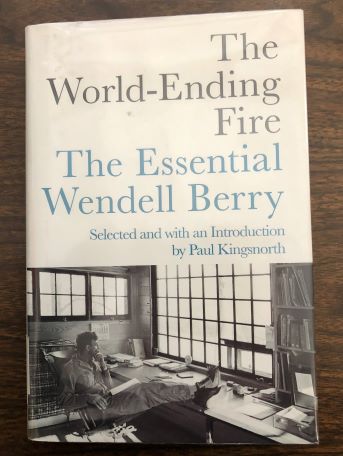

I met Ken at the first funeral after the terrible Hyden coal-mine disaster in Eastern Kentucky, Dec. 30, 1970, and he kept going to funerals for most of the 38 miners. Later he began working with me all over Appalachia. In March of 1972, we got together when a coal-mine’s lethal lake of waste water broke loose and drowned 125 people along Buffalo Creek, W. Va, one rainy Saturday morning, with no warning from the coal company. Ken and I decided to look around for more of these “slurry ponds” and got caught in some deep woods, by a few guards flashing pistols. As we tried to explain it was all a big mistake, Ken whispered to keep edging our way down to the state road, to public land, which we did, safely. Some of my best times were spent out on the road somewhere, with Tom Hardin of Kentucky, Don Hogan Charles of the NYT, Gary Settle of the NYT and Seattle, Chang Lee of the NYT, John McDermott my soccer buddy from San Francisco and now Italy….and more. And the news about the digital project makes me happy that the Times will preserve the work of its own artist-journalists, in its way, a hall of fame for these people who became legends to me. (This is one of those pieces I hate to write, but am compelled to do.) It was March in 1953 and I bumped into John Vinocur in the GG subway, the local that ran underneath Queens Blvd. John was a year behind me in Junior High 157 but we had gotten to know each other on the daily ride to Rego Park. The headlines in the papers – everybody read a paper in those days – The Daily News! The Times! The Trib! The Mirror! – and these were just the AM papers -- were about the death of Joseph Stalin on March 5. The question was, would the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S. be lessened or heightened by whoever came next, a fun discussion in any decade. John was a news junkie and so was I and we chatted animatedly, and no doubt loudly and ostentatiously, until the GG local had arrived at our stop. I thought of that subway ride when I read that John passed Sunday in Amsterdam, yet another great city he knew from his time as reporter and editor at the Associated Press, International Herald Tribune, New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He lived the dream that was perhaps in our brash Queens minds on that March morning of 1953. The obituaries tell of his accomplishments and hint at his bluster. I know somebody who worked in the Paris office of the IHT for a year in the early 80s – “dashing and vibrant” were the words she used. That was when the IHT was an eccentric wing of the Times, its office never far from the Champs Elysées, its product a must-read for ex-pat or vacationing Americans, long before the Internet. News from home! Sports scores! It was the offshoot of the paper being hawked by Jean Seberg – “New York Herald Tribune!" – in Paris, as Jean-Paul Belmondo sharks her, in the 1960 movie “Breathless.” That was the same world sought out by John Vinocur, who had played a little basketball at Forest Hills High, went to Oberlin, and then off to France, where he played semi-pro basketball. The hoops were part of his rep, and he often mentioned it to me, knowing I would be properly impressed. At some point, John went to work for the Associated Press in Paris, earning good assignments like the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Here is eager young John Vinocur, covering the massacre of Israeli athletes, described by another deceased pal of mine, Hubert Mizell, late of the St. Petersburg Times. "A native New Yorker, he… matriculated to backwater France, learning the language from natives and picking up money playing semi-pro hoops.” Hubert then describes how John “ignored police warnings and scaled a fence to get close to Building 31.” That would be John from Queens, scaling a fence. I can find no reference in his obit to how John got his job at the Times, but as I recall it, John was working for the AP in Paris when the movie “Last Tango in Paris” came out, portraying the club world of Paris in all its seediness, and John went to one of the raunchier clubs and wrote about it, and somebody at the NYT noticed. That’s how it worked: somebody likes your clips. John worked in the home office of the NYT for a while but my guess is he was used to being The American in Paris, so he went back. We ran into each other over the years, and would share opinions of New York sports, our Queens voices the loudest in any brasserie or café, still bonded from the GG local subway. *** If you can leap the paywall, you can find Sam Roberts’ obituary of John Vinocur here: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/06/obituaries/john-vinocur-dead.html *** And just to get a feel of the dream, Paris in the 60s, here is the clip from “Breathless:” One of my main regrets from my long association with the Commonwealth of Kentucky is that I have never met Wendell Berry. He was already a name in the papers – the poet who wrote with a pen or pencil, the agrarian who warned against forgetting the old ways of farming. He is still at it, age 87, somehow surviving without a computer or television, on his land in Port Royal, and still publishing whenever he feels like it. Finally, finally, with fires raging and tornados rampaging and strip-mine detritus floating past his farm on the Kentucky River, I picked up one of Berry’s most recent books, “The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry,” Selected and with an Introduction by Paul Kingsnorth, published by Counterpoint Press in 2017. Well, never too late – at least to read and honor Wendell Berry, if not to act on his warnings. Those issues were already out there from 1970-72, when my family moved to Kentucky for the Times, for me to cover Appalachia, and, as my wife puts it, “George lived in Harlan and I lived in Louisville.” Certainly, I covered what Wendell Berry preached – the damage from gouging coal from the fragile surface of the Cumberland Mountains; the need to farm intelligently and personally, not by corporation; the sellout by politicians who scorned the land for their own profit. (See: Manchin, Joe, a/k/a Blind Trust Joe, Commodore Manchin, and Worse.) But why didn’t I try to flash my NYT credentials and try to arrange an interview with Wendell Berry and his wife-partner-fellow-agrarian Tanya Berry? Goodness knows, I got around Kentucky. I met Harry Caudill, whose book “Night Comes to the Cumberland” made me want to go to Appalachia, to write about it. I got an epic private tour of Gethsemani Abbey outside Bardstown, and met the monk-colleagues of Thomas Merton, a few years after he died in 1968. I visited Pauline Tabor, the famed madam of Bowling Green, Ky., at her tasteful home with her majolica collection. I went campaigning with Happy Chandler on his nostalgia-trip final campaign. I got to know the McLain Family Band out of Berea. I also met Jean Ritchie, originally from Viper, Ky., the personification of Kentucky folk music, who also lived in our home town on Long Island. In Louisville, we lived next door to Rabbi Martin Perley, brave civil rights advocate, and his wife, Maie Perley, a writer. And I depended on the superb journalism of the weekly paper, The Mountain Eagle ("It Screams!") in Whitesburg, bravely issued by Tom and Pat Gish. And I interviewed Sen. John Sherman Cooper when he announced his retirement (in an era when Kentucky Republican senators were not necressarily vile.) Oh, yes, and I interviewed Loretta Webb Lynn of Butcher Holler, Ky., on the morning after she won country music’s Entertainer of the Year in 1971, and we stayed in touch. So you tell me: why didn’t I try to meet Wendell Berry?  His words and messages are very much out there. My Appalachian “correspondent,” Randolph Fiery, originally from West Virginia, often cites Berry as a spiritual and ecological inspiration, so I took out the book from the great Nassau County library system. Berry had me in the first pages of the first selection, “A Native Hill,” written in 1968 – in which he describes his odyssey in his 20s from academic and writer in the great cities to return to the land, owned by his family for six or seven generations. He follows the trickle of water toward the larger streams below: “As the hollow deepens into the hill, before it has yet entered the woods the grassy crease becomes a raw gully, and along the steepening slopes on either side. I can see the old scars of erosion, places where the earth is gone, clear to the rock. My people’s errors have become the features of my country.” Berry’s words touch off memories of the first house we bought, out east of Louisville, in an old place called Prospect. Builders had carved a freaking golf course into the plateau and our new house sat on the western edge, facing undulating plains – including a family cemetery. (The realtor promised us there would be no further development.) A trail led downhill, following the trickles, toward Harrod’s Creek. I loved walking alone in the woods – well, until a few months later a chunk of rock landed on our back lawn, nearly missing our youngest child -- from dynamite by a crew expanding the sub-division. Turned out the real-estate agent had lied, so we moved much closer to town, but my love of the woods remained. Now I recognize the very same flow of land in Berry’s descriptions of his family farm – from utilitarian Indian paths to dirt roads widened by soldiers and now, not far from his home, “its modern descendant known as I-71, and I have no wish to disturb the question of whether or not this road was needed.” I think of how many times I – or my family of five – barreled back and forth along I-71 toward home (New York) or the nearest city with baseball and other urban pleasures, that is, Cincinnati. Turns out, Wendell Berry’s farm – where he still farms and writes – is an hour to the East End of Louisville. But I never tried to interview Berry about ecology or strip mining or the diminution of family farms.  Berry’s beliefs resonate in his articles over the decade. In the chapter “Family Work,” Berry laments the long hours modern children spend cooped up in school: (“why should anyone be surprised if, under these circumstances, children should become ‘disruptive’ or even ‘ineducable’”) And in “Economy and Pleasure,” he describes the joy of taking his 5-year-old grand-daughter out to work the two-horse team in plowing some family land, and how she took to the reins. (I will not divulge her charming comment at the end of this utilitarian joy ride; she addresses her grandfather as “Wendell.” Cool.) For me, the last chapter was the best – “The Rise,” from 1969, as Berry describes a six-mile canoe sojourn down the Kentucky River – in mid-December – when the water was high, bringing him closer to modern life on the shores. The chapter reminds me of times I went out on Harrod’s Creek.with my friend, Dr. Sid Winchell. In "The Rise," Berry takes the reader to the time of the Shawnee and the arrival of Gen. George Rogers Clark to the still peaceful flow of the Kentucky River, even with all the debris floating alongside the canoe. Berry’s long life of farming and writing and loving the land awaken my sensibilities. I already mourn the new “settlers” in our wooded corner of the suburbs, who cannot wait to hack down trees, despite the first aid trees furnish a grievously wounded planet. Wendell Berry has been preaching to us for more than half a century. Long may he write. By pen or pencil, of course. *** (Mea culpa: written on a ThinkPad, using a Word program, issued by the Weebly site, via the Internet.) *** https://berrycenter.org/ Nice article by Silas House in 2020: https://gardenandgun.com/feature/wendell-berry-the-poet-of-place/ Henry Aaron. Tommy Lasorda. Jim (Mudcat) Grant. Poring over the magnificent two-page spread in the Times, honoring prominent people who passed in 2021, I realized I could write reams about stars I knew from the locker rooms. I could also recall famous people I met here and there – Colin Powell, streetwise New Yorker ---- Vartan Gregorian, kind Armenian wise man -- and Larry Flynt, seedy champion of pornography, who happened to be a hilarious and incisive interview. But my heart, at year’s end, is remembering relatives and friends I got to know up close, who have left a personal gap. As Arthur Miller wrote: Attention must be paid. Aunt Lila. She was my wife’s aunt – helped raise her -- but she also became my aunt, jolly and chubby with a beautiful smile and a generous hug, over the decades, sidling up to me and asking about our children, our work (she had an admirable curiosity), and whether I knew the Lord. Her children and grandchildren cared for her in old age, shuttling her from northeast Connecticut to suburban Long Island, keeping her going, medically and socially. At a reunion last summer at a daughter’s home, Aunt Lila was wan, low on energy, and Marianne sat by her all afternoon, sensing this might be the last time, which it turned out to be. But Aunt Lila’s smiles and hugs and kind acceptance linger on. Captain Curt. Once a point guard on very good basketball teams at Hofstra, Curt Block became a publicist at NBC and had other memorable gigs. (As a young reporter, he interviewed young Cassius Clay, and had the presence of mind to keep the rudimentary tape, re-discovering it in old age.) When aging baseball and basketball players (and one scribe, me) began to meet periodically at Shaun Clancy’s great place, Foley’s, Curt took the slow train up from Philadelphia and became the greeter, the treasurer, the captain, sitting in the middle, enjoying everybody else’s stories, moving the ball around, as he had against Hofstra’s opponents, back in the day. He quietly alluded to impending heart surgery, and last summer he went to sleep and did not get up. Because of the pandemic, the old boys have not been able to meet since, to uniformly mourn our quiet leader. Neighbor and Nurse. Ann Schroeder was a nurse in the Bath-Brunswick area of Maine. She got to know my wife’s Uncle Harold (older brother of Aunt Lila) and she became a volunteer guide to his old-age miseries. We got to know her through her detailed emails, explaining Harold’s health problems, what was being done, so we could assure his relatives that he was surrounded by skilled, loving friends in that wonderful area that has become our own sentimental home. After Harold passed, we stayed in touch – via health newsletters Ann sent. She casually alluded to her own breathing issues, and last summer she noted that she was now on hospice, and then the e-mails stopped. In keeping with this understated woman, her service was private.

Mentor to Surly Luddites. Howard Angione was a reporter who somehow wandered into the emerging technology age at The New York Times, in the mid-1970s. With the reserved air of a theologian, he had to introduce temperamental reporters to the bulky Harris terminals now placed around the City Room. Sometimes these terminals would swallow articles whole, provoking profane tantrums from cranky news reporters like, well, like me. Howard’s motto was: “If I can teach Vecsey, I can teach anybody.” Which he could. After his missionary work in the City Room, Howard went to law school and specialized in elder law, until he became an elder himself. The NYT did not note the passing of the tutor who helped modernize the paper, but the Portland (Maine) Press-Herald did. Zone-Buster Poet. Stephen Dunn was a rather shy jump shooter who could beat down a zone defense. On one road trip, he heard two older Hofstra teammates discussing a novel, and he realized jocks could also be scholars – and later he began to write poetry, ultimately gaining a Pulitzer Prize. His later years were spent fighting Parkinson’s disease, which got so bad that he could not recite his own work. Our friend, once known as “Radar,” was deservedly included in the NYT’s gallery of notables in Friday’s year-end necrology. My Cousin Artie. From my earliest memories, I admired Art Spencer, my oldest cousin. He was so cool – riding a two-wheeler, driving a car one summer in rural Pennsylvania, with friends who had musty, mysterious barns amid lush corn fields, going to college, going into the military, marrying, starting a family. At family gatherings – some joyous, some sad – I had to practically pry out of him that he and Shirley had a flourishing crafts business, designing house signs – staples at weekend crafts exhibits near Ocala, Fla. The women in his family cared for him lovingly in his final months, and then staged – sign of the times – a Zoom service to honor an understated and artistic life. Agent and Friend. Philip Spitzer was my agent who negotiated a durable contract with a publisher and the manager of Loretta Lynn – a project in 1974 that turned out to be the book and the movie, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” I can still see Philip -- suave, part French, athletic, sitting on Berney Geis’s rooftop patio in Manhattan, holding his own, word by word, paragraph by paragraph, with two legalistic sharpshooters. We became family friends, his three children, my three children, good memories, even if the guy would never, ever, let me win a tennis set or a basketball game. Even after we did not work together, we stayed in touch, and as his health deteriorated, he passed the Loretta project to his capable oldest child, Anne-Lise Spitzer. This magnificent seven stands in for all the people in my life who passed in 2021. As far as I know, Covid did not figure in any of their passing – just the inevitable erosion of time, long and good lives, now ended. Our best wishes to all who read this tribute. As one often hears in corners of New York: Be Well.  As soon as the final out settled in Freddie Freeman’s glove, I felt a surge – not quite the relief I felt when the Covid vaccine arrived in my arm but rather the excitement of a great swath of free time, suddenly arriving. Book time. I wasn’t reading hard-covered books during the warm months, but I kept taking notes about books I wanted to read. Now, no more long evenings obsessively watching the hapless Mets organization fall apart, in the person of Jacob deGrom’s pitching arm. Now, World Series over, free at last. The first book has been “The Taking of Jemima Boone,” by Matthew Pearl, about the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s most spirited child, on July 14, 1776. I was drawn to the subject because Daniel Boone was all over Kentucky when I lived in Louisville for two years, as the Appalachian news correspondent for the NYT, wandering the region. Boone's statue and name were all over the Commonwealth of Kentucky, as I drove on twisting roads that had been paths for him to explore, to hunt, to escape. But somehow I never wrote about him in all the time I roamed around Kentucky. Now Matthew Pearl, a novelist by trade, has written a taut drama, with a thick index in the back, assuring me that he was using source material and not only his novelist’s imagination. It’s a tricky time to be catching up on an American icon, most known for barging into Native American territory, often fighting for land, as well as for his life. The U.S. is re-evaluating its memorials to slave-owning Confederate generals, as well as explorers like Columbus. What to do about Daniel Boone? The reason Jemima Boone and two other girls in their early teens became prisoners is that Daniel Boone could not, would not, stay in coastal towns but pushed west through the Cumberland Gap and on, losing a son, driven by a tropism for space and land and “freedom.” This American icon was taking other people’s land -- at gunpoint – but his relationship to the people of the land was more complicated than that. He became part “Indian” in style and spirit. He was captured by a complex chief, Blackfish, who adopted Boone as a son, and recognized him as a kindred soul, with skills and courage. Boone, of course, was planning his escape. The actual “taking of Jemima Boone” occupies the taut first 75 pages of this book – how she tried to fight off the men who surrounded their canoe, how she left signals for the man she knew would come looking for her, and how she bonded, in a way, with the son of Blackfish, who treated her with respect, by all versions. Pearl, the novelist, resists going too far in suggesting a romance between captor and captive. In fact, one of the things I have learned from recent reading about New England settlement is that Indian males almost never raped, although some did “marry” their captives. It never came to that in this Kentucky encounter, but the details seem to have survived (with revisions, with exaggerations, surely) into the 19th Century, and then the 20th, and now the 21st. Matthew Pearl makes it real. Daniel Boone kept going, all the way to Missouri, where he and his wife Rebecca and Jemima Boone all died – of old age. He has two graves, one in Missouri, one in Frankfort, the Kentucky capitol. I recommend “The Taking of Jemima Boone” as a well-written and well-researched visit to a distant time, leaving complexities in a nation now re-examining (at long last) its myths and heroes.  I rarely read fiction these days; so much to learn from non-fiction. In spurts of reading, I have belatedly learned about Neanderthals and evolution and DNA, as well as the earliest “settlers” of New England. This has been spurred by my wife’s vast personal research in the genealogy of her family, from England and Scotland. Next in my reading list: “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer I was drawn to the book by a review by Joe Klein in The New York Times, with this overview: “Albion’s Seed” makes the brazen case that the tangled roots of America’s restless and contentious spirit can be found in the interplay of the distinctive societies and value systems brought by the British emigrations — the Puritans from East Anglia to New England; the Cavaliers (and their indentured servants) from Sussex and Wessex to Virginia; the Quakers from north-central England to the Delaware River valley; and the Scots-Irish from the borderlands to the Southern hill country. I consulted the index and found this one reference: “When backcountrymen moved west in search of that condition of natural freedom which Daniel Boone called ‘elbow room…’” Do these four separate waves of emigration explain why the United States, perhaps more than ever, seems to be several different countries, with rival impulses and outlooks? Does it explain Red and Blue states or regions? I look forward to learning what Fischer has to say.

One of my favorite scenes in all the Sopranos episodes -- plus, nobody dies.  There is a terrific article about the enduring appeal of the Sopranos’ series, in this Sunday’s magazine section of The New York Times, already online. The writer Willy Staley, an editor of the NYT magazine, claims the series is extremely popular with younger people who were too young to watch it during its heyday. Why? The Sopranos are trying to hold on to their thuggish edge in an apocalyptic world where all the rules are gone, even for gangsters. Until I read this article, I had never seen the broader picture – I had laughed at the funny lines even when my stomach was churning, knowing what was going to happen to characters like Big Pussy or Adriana, in over her head. Who knew this was actually about America? But then the magazine article popped up online, describing Tony’s world of expensive suburbs, with everybody emulating gangster architecture, until the palaces met in the middle. No taste, no privacy, even for a gang lord. Then on the very day of the magazine article, I was watching the televised Congressional budget death dance, and there was Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, ostensibly a Democrat, jutting out his jaw in a narrow corridor, being pestered by a reporter. The pesty reporter, Ari Natter of Bloomberg News, asked Manchin if his view on protecting the dying coal industry was colored by the fact that his son ran a coal company and Manchin received profits from it. “I’ve been in a blind trust for 20 years,” Manchin said, hard-faced. “I have no idea what they’re doing.” “You’re still getting dividends,” the reporter persisted. “You got a problem?” Manchin asked. When the reporter asked another question, Manchin snapped: "You'd do best to change the subject." (Published reports say Manchin has made $500,000 in coal dividends. The family is busy. Daughter Heather Bresch once presided over a drug company, Mylan, when the price of EpiPens soared to $600 a shot. And Gayle Conelly Manchin, wife of the senator, is now the federal co-chair of the Appalachian Regional Commission, no doubt taking care of the poor folks in the hollers. That's the way it works in Appalachia.) Seeing Joe Manchin in action, I thought immediately of how Tony Soprano’s face would darken as he menaced somebody. I thought of how Furio, Tony’s muscle man, nudged the uncooperative doctor into the golf-course water hole, up to his ankles. * * * I know there is a prequel about the Sopranos coming out, but I think I’ll skip it. For me, that world, that series, ended – quite appropriately – with no resolution about what happened to Tony and his family. I usually postulate that the evening in the restaurant ended prosaically, and Tony and Carmela found a way to get out of the business, changed their fingerprints and moved to Boca Raton. (I bet Tony even plays golf.) Maybe, in their new lives, Tony and Carmela watch TV as Joe Manchin struts down a Congressional corridor, pretty much saying he doesn’t care what happens to all those people. He’s got his. Tony: “That used to be me.” * * * Read the great NYT magazine article for yourself: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/29/magazine/sopranos.html The 2020 Tokyo Olympics have already begun -- a year late and quite unwisely.

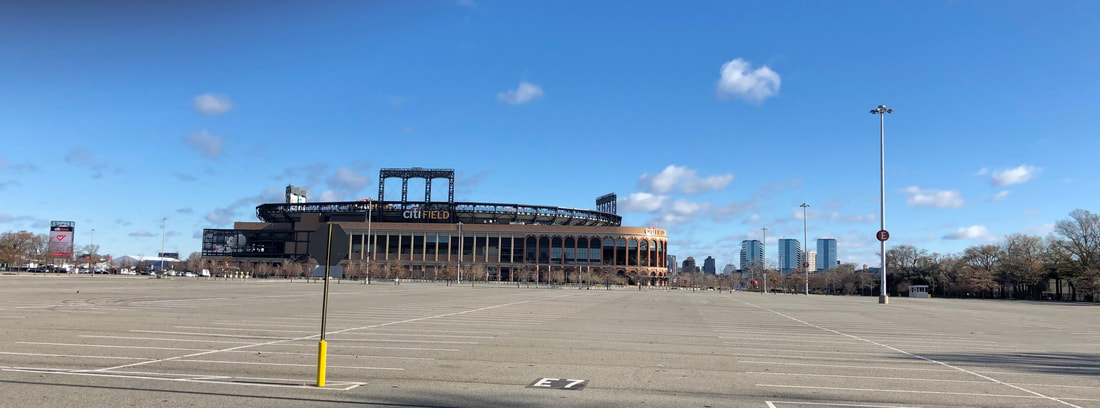

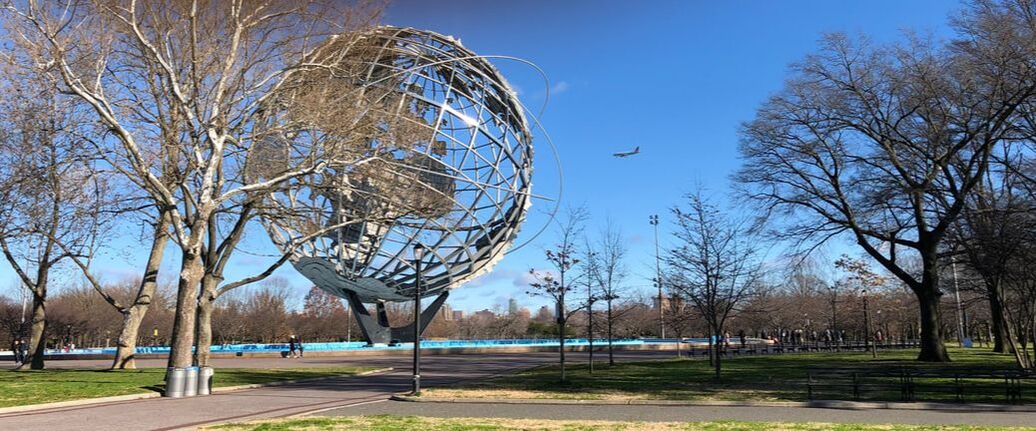

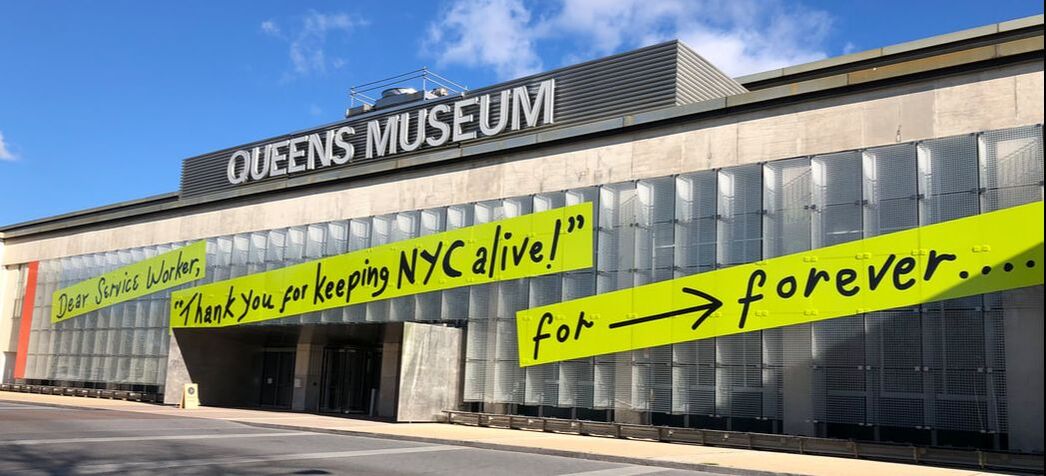

The American women soccer team got blasted by Sweden, 3-0, on Wednesday in Japan, in some early tournament action, before the Opening Ceremony Friday night. So now the Games are official – gritting their way toward the finish line, in the face of a worldwide pandemic that humans of all nationalities and political systems have been too stupid to control. This has been evident as the International Olympic Committee and the Japanese organizers willed the Games to begin, despite another surge taking place. Athletes are already testing positive – and this is before they were shoe-horned into a dense city, into Olympic hideaways where athletes are theoretically sequestered. But why should the IOC and the hosts show sense when most of the world is giddy on the concept that we are back to “normal?” I already agree with the skepticism collected by the great reporter, John Branch, in the NYT this week. Branch talked to observors around the world, who wondered if it is time to end the Olympic Games. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/17/sports/olympics/tokyo-olympics.html After covering seven Summer Games and four Winter Games, from 1984 into 2010, I was veering toward the position that the Games existed mostly because of television money, blaring commercials around the world, but costing far more than they generate for the host countries and victimized host cities – all in the name of a faux ideal. I know I became disenchanted with the Olympics when I saw cities and entire countries disrupted by the demand for specialized Olympic facilities. After the two-week festival, the traveling circus packed its tents and moved on, it mostly left the detritus and debt behind, as documented in John Branch’s article. My first Games were in 1984, when Los Angeles and top executive Peter Ueberroth used existing facilities in the region, producing a profit for amateur sports groups, not debts for the host region. Some other host cities tried to think of leaving a lasting upgrade – Barcelona, in 1992, for example, and to my surprise, Atlanta's downtown was upgraded by the Olympic presence -- but others just spent and spent for a 17-day jamboree. Having said that, I must add that some parts of the Olympics were wonderful to cover – great events intriguing personalities, in special places all over the world. I always tried to keep my perspective of whether these Games had lasting value for the cities that lusted to be the host, but I do have memories of events and competitors: In Los Angeles in 1984, I had the good luck of watching a charismatic American volleyball team, with a lanky, thoughtful star named Flo Hyman, lose the tense gold-medal match to China. For me, that one tournament was as good as any sports playoff or tournament I have covered. My first Winter Games – Calgary, 1988 – reminded me that I don’t like being cold, so I gravitated to events with a roof over them, like figure skating….and hockey…and speed skating, with rocking music and gaudy costumes as powerful athletes whizzed around the oval track. The Olympic ceremonies often had the air of ersatz royalty – coronations! knighthoods! weddings! – but once in a while they touched the heart, as in 1996, in Atlanta: the final carrier of the Olympic torch, on a runway high above the stadium, turned out to be Muhammad Ali, already suffering from the Parkinson’s disease that would kill him way too young. We held our breath and prayed for him, as Ali willed himself to complete his mission. In those same Atlanta Games, in the first Olympic soccer tournament for women, epic Americans like Michelle Akers, Julie Foudy and Mia Hamm won the gold medal. In 2002, in Salt Lake City, Sarah Hughes, not yet 17, blended talent and will in her stunning gold-medal figure-skating routine. I had written about her family, John and Amy Hughes and their five other children, good people, who lived near me on Long Island. Sarah Hughes is now a lawyer in New York City; her dad, John Hughes, a great hockey player from Cornell, passed in August of 2020. I admit, I often slipped out of the Olympic bubble, to see how real life was going on in the host nation. At the 1998 Winter Games in the modest Japanese mountain town -- Almost Heaven, West Nagano, as I called it – I watched residents sweep overnight fluffy snow off the sidewalks. In Athens in 2004, my wife and I played hooky one day, taking the slow ferry to Hydra and swimming off the rocks. In Beijing, Chris Clarey and Jennifer 8 Lee and I visited one of the old neighborhoods – a hutong – and ate in a restaurant run by Uighurs, the persecuted ethnic minority. But maybe my best “Olympian” moment came in 2004 when the shot-put competition was held on the grounds of the very first Olympic games in 776 BC, in the Olympia region west of Athens. To inhale that dust was a grand honor. Since I retired at the end of 2011, I admit, I have never watched a minute of Olympics Games, Winter or Summer – too much babble, too many commercials, too much else going on. In the next few weeks, I will rely on the NYT’s great staff to provide the words and pictures --- and I hope everybody gets through without calamity.  The NYT plant in College Point. (Photo borrowed from the Web. The other photos here are via my smartphone.) The NYT plant in College Point. (Photo borrowed from the Web. The other photos here are via my smartphone.) Don't we all have things we miss in this pandemic -- beyond family and friends? I miss my home town twinkling on the western skyline. I wrote about this a few months ago. www.georgevecsey.com/home/i-miss-my-home-town On Sunday I did something about it. With the plague at full blast, I had to deliver something to the NYT plant in the College Point section of North Queens. It was a cold day, very little traffic. Ideal driving conditions. My muscle memory told me how to handle the turns and merges and quick decisions of parkway driving in the city, With every mile, my exhilaration grew. First stop was the NYT plant; since my retirement in 2011, I have become friendly with the people there. On a quiet Sunday morning, I dropped off the item and kept going.  The museum had large banners facing the Grand Central Parkway. I remembered one winter in junior high school, when I went ice skating in this building with some classmates. Now it is a vibrant community asset; I thought of my friend who helps run it, and the Panorama of New York City, where we have "bought" our family home in Holliswood. I drove around to the front of the awesome building on the glacial hill. My mom was in the first wave of students in the new building -- in 1927. She loved the school as much as I do; it was our major bond, She passed in the very nice Chapin Home, a few blocks away, in 2002. The city, in its dunderhead way, terminated Jamaica High a few years ago -- a DiBlasio failure -- but there are several smaller schools tucked away in the building that will last forever. I drove along Henley Rd., near the house where the worst president in American history used to live, soiling the image of Queens. There was no time for a drive past our old house, where my mom moved nearly 100 years ago; I had to pick up my order of Shanghai dumpling soup in Little Neck. My Sunday morning excursion temporarily dispersed the miasma of the murderous pandemic.

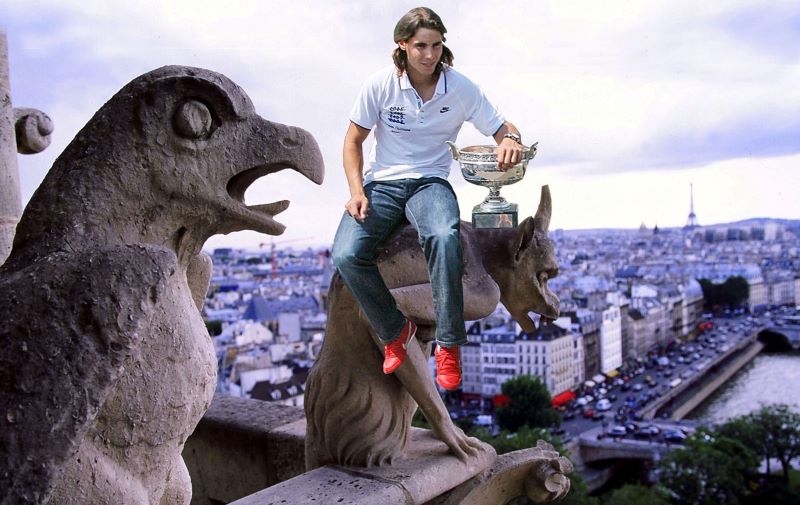

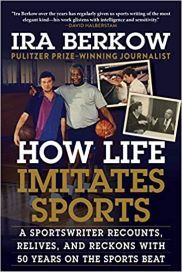

I'll keep in touch with the many dozens of my Jamaica contemporaries; we are very tight. Maybe some quiet Sunday morning soon, I will drive into The City (Manhattan, that is) -- just to see it.  Not too long ago, Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow were gracing the sports pages of The New York Times with their wise columns. Now they are both issuing books with their very personal views of the world. Harvey’s book is “Our Last Season: A Writer, a Fan, a Friendship,” about the bond between him and Michelle Musler, who for decades was a fixture in the stands just behind the Knicks bench in Madison Square Garden. Ira’s book is “How Life Imitates Sports: A Sportswriter Recounts, Relives and Reckons With 50 Years on the Sports Beat,” which just about tells it all. (In alphabetical order) Araton praises the wise businesswoman who was always there – for the Knicks and for him. He describes himself as the child of a project in Staten Island, who earns his entry into sports journalism while battling his own insecurities. As he works his way from the Staten Island Advance to the Post to the Daily News, his talent and earnestness impress not only editors and readers but also a fan literally looking over his shoulder in the Garden. Musler saw all – could read the body language, maybe even read lips, of the Knicks and the opponents and the refs. She had put her people skills to great advantage in the corporate world, undoubtedly by being wiser than the average (male) executive. The Knicks were her outlet, she freely told friends, her social life. Everybody knew her – the players, nearby fans, reporters, ushers, even the team PR man, who left a packet of media stats and releases for her before every game. How cool was that? Musler more or less adopted Harvey, counseled him, shaped him up, told him to aim big. She became friendly with Harvey’s wife, Beth Albert, and sometimes met Harvey after a game to debrief him on what she had seen from her perch. When he fretted whether he was worthy of the Times job being offered, she figuratively slammed him up against a steel locker and gave him what a high-school coach I knew called “a posture exercise.” And when his career took a sour detour, she shaped him up, to the point that in retirement he remains an extremely valuable contributor to the Times sports section. Harvey is still what somebody once called him: “The Rebbe of Roundball.” In return, Harvey came to know Michelle Musler – her strange childhood, her husband leaving her with five children, her career, her need to make money, her love of the Knicks. Her decades of working with male executives prepared her for a searing analysis of James Dolan, the miserable owner of the Knicks. As Michelle’s health deteriorated, Harvey would sometimes drive from New Jersey to Connecticut to the Garden to get her to a game. And when Michelle Musler passed in 2018, Harvey wrote a beautiful obit for the Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/obituaries/michelle-musler-courtside-perennial-in-the-garden-dies-at-81.html  Ira Berkow’s book is also personal – about a talented, ambitious kid from Chicago who made his way to New York and became a fixture in the Times and also in books, not all about sports. Ira has touched on most stars of the past half century – Muhammad Ali! Michael Jordan! He sized up O.J. Simpson, before and after! He had lunch with Katarina Witt! He shot baskets with Martina Navratilova! He also shot baskets with a retired Oscar Robertson! He schmoozed with Abel Kiviat, then America’s oldest living medalist! And he scrutinized a brash real-estate hustler named Donald Trump! One of my favorite segments is about Jackie Robinson – who broke baseball’s disgraceful color barrier in 1947. Ira recalls being 15, a high-school athlete himself, watching the Dodgers take on the Yankees in the 1955 World Series. In 2018, with JR42 long gone, Ira was being interviewed on TV about Robinson and came up with a description of how Jackie Robinson had faked the Yankees’ Elston Howard -- a catcher playing left field -- into throwing the ball to second base while Robinson steamed into third. Later, he remembered interviewing Robinson in 1968 about his thought processes in testing Howard, who was out of position because Yogi Berra was the catcher. Robinson seemed to deflect Ira’s analysis, but the audacious move remained in Ira’s fertile brain. A few years ago, Ira looked it up in the official play-by-play for the 1955 Series: it confirmed that Robinson, by whatever logic, had victimized Howard into throwing behind Robinson. This section confirms the instinctive genius of Jackie Robinson and also the enlightened journalistic observation powers of Ira Berkow. * * * Most of sports have been thrown off balance by the pandemic, but these very different books by Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow remind us how great sportswriters have enriched us by writing about the world, on and off the court. Four superstars, overlapping. I am referring to Rafa Nadal, one of the nicest people I have met in sports, who won his 13th French Open on Sunday. I am also referring to Chris Clarey and Karen Crouse of the NYT, who wrote about Nadal in the Monday paper. And I am also referring to Art Seitz, master tennis photographer, who has been snapping away, well, forever. I loved reading about Nadal and seeing Art’s photos, having become a Nadal fan in 2011, the only time I met him. I had heard he was a good guy, a sportsman, and he lived up to his reputation on a miserable day, with the remnants of Hurricane Irene lashing New York much as the tail end of Hurricane Delta was drenching New York on Monday. He had done his obligatory media conference and was eager to get back to Manhattan, but he was promoting his book and had promised me a few minutes for an interview. We got into a conversation, and I mentioned that I had covered eight World Cups by then, including my first, in his country, Spain. I think it's fair to say that reporters do not expect their subjects to show much, or any, interest in them. But Nadal seemed intrigued that an American knew and loved soccer, even my modest dose of knowledge. I knew that his uncle, Miguel Angel Nadal, had been a mainstay for Johan Cruyff at Barcelona in La Liga in the 90s, and I had covered Spain’s World Cup championship in 2010. So we talked soccer…as well as tennis….as well as his penchant for cooking for himself and entourage on the road. He could have ducked out at any time, but he stayed and talked, and my impressions of him since have been confirmed – a centered person who has willed himself to the top of tennis, and can speak with compassion about the pandemic, knowing it is more important than tennis. My pals Chris Clarey and Karen Crouse caught him perfectly in Monday’s paper – Chris concentrating on the match and the career, Karen focusing on his values and his acquired trilingual abilities. When I first saw Nadal nearly two decades ago, he could not speak any English in public. Now he is eloquent, from the heart. Felicidades, Rafa. Chris Clarey:

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/11/sports/tennis/nadal-french-open.html Karen Crouse: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/11/sports/tennis/french-open-rafael-nadal.html My article in 2011: https://straightsets.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/28/off-the-court-nadal-wears-chefs-whites/ For a sample of Art Seitz tennis photos, check out his Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/100001883302306/posts/4593499944056070/?extid=0&d=n Oh, my goodness, it was 20 years ago.

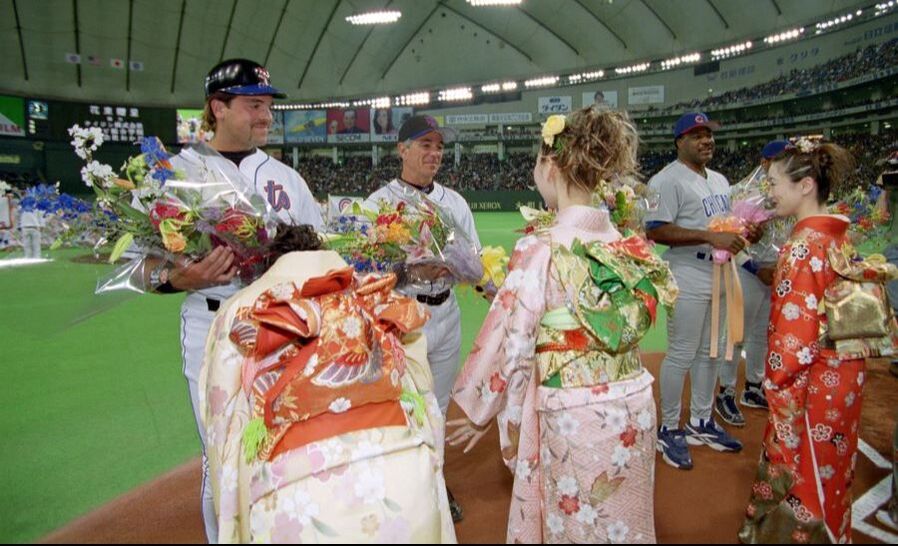

Today, the NYT reprinted an article I wrote 20 years ago today, on the Mets-Cubs league game in Tokyo. It was a pleasant surprise to be back in the paper and be reminded of a great trip and how much I love visiting Japan. This, at a time when there is much sadness at postponing the Tokyo Olympics to next year. ごめんなさい Gomen'nasai (I am sorry) The article jumped out of the Monday sports section – about Benny Agbayani’s grand-slam, pinch-hit homer in the 11th inning that defeated the Cubs. /www.nytimes.com/2000/03/31/sports/baseball-against-the-odds-agbayani-gets-mets-home-even.html?searchResultPosition=1 It was the end of a grand assignment – two Mets exhibitions around Tokyo, plus two official games, showing me how much the Japanese fans know about baseball, and America. It kicked off so many memories: ---Japanese fans booing good-heartedly when activist Mets manager Bobby Valentine (with his love and knowledge of Japan) had Sammy Sosa walked intentionally with first base open. “Japanese fans never boo the manager for this,” a Japanese reporter told me. “But they know it is normal in American baseball.” How cool – like young couples on Friday date night, going to TGIFriday’s glittering outlets all over Tokyo, for ribs and fries. ---Standing outside the Tokyo Dome that week, watching fans congregate and spotting a woman wearing a Mets uniform with Swoboda 4 on the back. Haruko told me, in quite good English, that she was a Mets fan – had seen a Nolan Ryan no-hitter in the States (for the Angels) and in fact had stayed with Ron and Cecilia Swoboda in New Orleans. ---The great Ernie Banks, retired by then, sidling up to me around the batting cage and repeating his iconic phrase: “Let’s play two.” ---How I spotted Masanori Murakami, the first Japanese national to play in the American majors – I covered that game, too, in 1964 – and re-introduced him to the Mets’ roving pitching coach, Alvin Jackson, who was his opponent in that epic debut. They laughed and shook hands and chatted, so comfortable with each other, as old players are. Alvin passed last year; I was so honored to have shared that moment with him. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/31/sports/sports-of-the-times-murakami-will-always-be-first.html?searchResultPosition=1 My other memories of that trip are less baseball-centric: ---Zonked on jet lag, taking my wife on the Tokyo subway, telling her how easy it would be, and emerging in sunny Ueno Park for a nice stress-free walk (and subsequent first meal in a neighborhood) ---Being driven from bustling Tokyo to a famous shrine by our former Long Island neighbors, Fumio and Akie, the nicest couple. Originally from Osaka, Fumio did not know every inch of Tokyo – does anybody? – but he relied on a novelty GPS built into his dashboard, and he negotiated all the tight little turns and ramps to get us on a freeway to a leafy shrine. --- Salarymen – and women – stopping to offer us directions when we appeared baffled by the odd numbering systems. --- After the baseball work, visiting historic Kyoto, where a woman addressed my wife in French; she had lived in France and loved to use that language. My wife, who speaks some French, sat on a bench and they chatted for an hour, about La Belle France. ---And finally, since it was 20 years ago this week, having people in Kyoto apologize to us because the cherry blossoms were late. In this grim spring, I think of all the places we cannot go, but when I think of baseball…and Japan….and friends….and spring...and having been privileged to go places and write stories, the day seems better. Jacob DeGrom was supposed to throw the first pitch to the champion Washington Nationals, a few miles west of me, on a sunny, cool day.