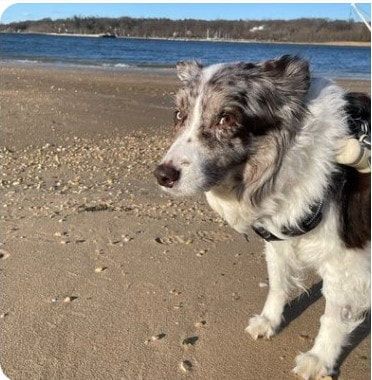

George and two buddies from Pennsylvania are visiting an exchange student pal and his family in Turkey, and getting a great tour. This is the rock formation in Cappadocia, with its ancient catacombs and eerie wind-blasted towers, which George pronounced as "Martian -- beautiful and slightly spooky." We told him we had stayed in the hilltop hotel in our epic visit in 2012, On Wednesday he was at Topkapi and Blue Mosque and Hagia Sofia. We expect a full update when he gets back. I called her Pretty Girl whenever she sat by my side. She must have known I was smitten, because she let me pet her and talk to her even if her immediate family members were right there. She was a Blue Merle Australian Shepherd, a highly desirable breed, tooled to chase sheep up a steep incline, sorting out dawdlers. She could muster her speed and power when let loose in safe terrain but she was gentle and domesticated in Dave and Joelle’s house, near us. She had beautiful color and soft hair and a sleek face. She could have been a model.  Max Scherzer Max Scherzer She was named Blue, for her right eye, alongside her darker left eye. Exactly -- just like Max Scherzer, the traveling pitching star, currently with the Mets. When I see Scherzer blowing hitters away, I think of Blue. (The web says 5 per cent of Blue Merle Australian Shepherds have one blue eye, a genetic variant.) (The web also says a small percentage of humans has one blue eye, from a common ancestor 6-10,000 years ago.) I never saw Blue show a temper, even when Isabel’s cat or Greta’s cat sauntered by. Blue tolerated the felines, shared food space and floor space. She was beautiful; she had nothing to prove. I am not a dog person (and my wife has major dog allergies), but I did love our highly neurotic and foul-smelling cocker spaniel named Ebony, adopted while I was out of town, and good sport that I am, I walked her and washed her, and in turn she cuddled at my feet when I was reading or napping. I always referred to her as “my last dog,” but I still get sad when I think about her (and think I smell her, two decades later) whenever I lie down on my couch for a nap. Most of my family loves dogs. My mother adored Taffy, whom she walked for exercise while gallantly fighting back Multiple Sclerosis, and my sister Janet and brother Peter both have dogs these days. Laura and Diane had Griffey, a springer spaniel who could haul driftwood out of heavy surf north of Seattle. When Laura was a sports columnist out there, she knew and liked Ken Jr., who asked why she named her dog Griffey. “Annoying….and cute,” she said, and Ken seemed okay with that. More recently, they had a little Lhasa Maltese mix, whom I nicknamed The Yapper, in homage to Donnie Iris and the Jaggerz and their hit song, “The Rapper:” The Yapper used to snap and snarl at me, even when I was feeding her or taking her for a walk. But as she got older and wiser, she sat at my feet and let me pet her. Peter and Corinna had Ginger, an English bred Yellow Lab whom Corinna took for long pre-dawn walks in the neighborhood, and when Ginger was fading, she was replaced by Finnbar Octavian, whom they also love. David and Joelle adopted Blue 10 years ago from the great North Shore Animal League, near us in Port Washington. She was said to be six months old, but maybe she was older, because she was so mature. In her first years, Blue had the energy of a teen-ager. We’d go in the back yard and I would boot a soft soccer ball into a far corner. and she’d bolt to get it, as if it were a wayward sheep. A couple of years ago, I sent a ball into a corner and she gave me a baleful look, one blue eye and one dark eye, as if to say, “Uh, I don’t do that stuff anymore.” Either way, she was still beautiful. A month or two ago, she stopped eating much, and began losing weight and her coat became splotchy and she mostly sat and watched. Her family sought good veterinary care, and the verdict was stomach cancer. While Blue could still get around, David took her to Bar Beach, where she loved to romp at low tide, and Dave posted it on Twitter. I came by to hug her one more time, and on Friday family members received a photo from Dave, of an empty collar with the name "Blue" on it. Marianne wrote: "She’s running up the mountain, free again. ❤ to her, on her way." Speaking of hills to climb again, may I offer this song, by Alice Gerrard, sung by Kathy Mattea.

For Blue: "Agate Hill." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Adm_rbwCZJU Best wishes to all the nice people who read My Little Therapy Website, and those who add their comments, making this a community of sorts.

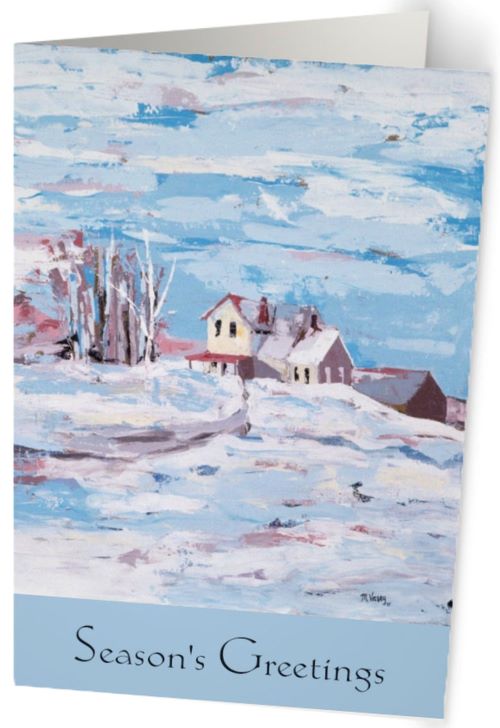

We give thanks for our blessings in the middle of all this. We know some people who are not well right now, and we wish for health. I am planning a little holiday pause, no words, no pictures, no opinions, just wishes for peace and health for all. GV (Painting by Marianne Vecsey; card crafted by David Vecsey.) Happy Father’s Day…Best Wishes at Juneteenth….and hopes for a good and healthy summer for all.

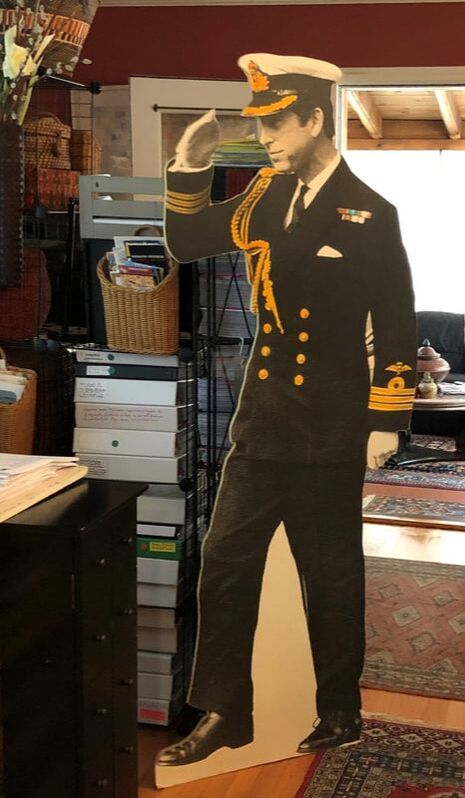

My first present – there are others – was a lovely essay in The New York Times written by one David Vecsey. The essay proved (once again, to me) that it is hard for me, being the least talented and versatile among the five members of our family. Marianne is an artist (more on that momentarily) and has a dozen other skills. Laura was a poet first and then a really good news reporter and sports columnist at four major papers around the country, and is now a real-estate maven upstate. Corinna worked in journalism (in Paris, later in New York) and is now a lawyer and consultant to feelgood projects in Pennsylvania. David could have (should have) been a sports columnist but after some time in the Web world, he learned newspaper editing from some good teachers at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and passed the editing test and tryout at the Times a decade ago, to our delighted surprise. So….a father and husband can brag on Father’s Day. My wife did it all. As David attests in his story, I was at the ballpark or typing in my room, putting in an appearance for meals or a catch or hoops or maybe a drive to Jones Beach or the city. I did take each of them with me on road trips to deepest America, not for games but for real life. Marianne did the hard work, the parenting. And it shows. They are all good parents. They all can cook. They all have spouses, Diane and Peter and Joelle, who match them, skill for skill, energy for energy, will for will, value for value. How blessed we are. David is usually busy putting the last bit of polish on articles for the Print Hub (that is to say, “the paper.”) He’s been working at home the past year, and instead of riding the railroad he has been able to develop other corners of his brain. In his younger days, he watched his mother cook, and sometimes went to the New York Philharmonic with her when I was away. He also watched her paint, in her “spare time,” late at night, her newest work materializing when we woke up in the morning. Over the years, she won prizes, appeared in nice shows and galleries, sold around 300 paintings, some of them now around the world. Recently, David asked if she had slides of her work, and yes, she had some tucked here and there. So he commandeered the slides, put them through the magic visual part of his computer, and turned some of them into posters and greeting cards, with themes and connections only his active mind could make. He has put them online, displayed them at crafts shows on Long Island, placed them in some nice shops, mailed the work to Berlin, to England, and corners of the U.S. It’s all on a very modest scale, and by Dave’s decree, some of the money is going to charity. The point was never money, it was the art, the work, the product, the result. I sit back and enjoy the smartphone pings from our scattered family. They are the best gift, on Father’s Day. * * * You should be able to open David’s story online today: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/19/insider/george-vecsey-fathers-day.html?searchResultPosition=1 For information on David’s project, Marianne’s work: https://www.etsy.com/shop/vecseyprinthub/  The Rosenthal china with such a long history The Rosenthal china with such a long history My friend Mendel Horowitz, who frequently comments here, has published a lovely piece about dishes that survived the trek from post-war Germany to Philadelphia and will now be used in Jerusalem at Passover this weekend. Mendel is a writer; you may want to read his touching article right now: https://www.jns.org/opinion/our-german-made-passover-seder-plates/ Mendel’s article reinforces connections I recently made between seders and my family’s Easter dinners decades ago – holy days in the early spring, with a touching similarity: the stranger, the visitor, in our midst. I met Mendel through this little therapy website – a rabbi and counselor of men, in Jerusalem, a long way from his childhood home in Queens. He is also a volunteer on emergency calls, never knowing whether the distressed people will be speaking Yiddish/Hebrew/English/Arabic, and it doesn’t matter. Oh, yes, he and his dad, Ahron are Mets fans. Last week I had the honor of “attending” the wedding of Mendel and Michele’s daughter, Leah, on a hilltop in Jerusalem. It was a vibrant, touching ceremony – with young women greeting virtual friends and relatives in distant lands, and the men singing familiar hymns. I was there. This weekend, for the seder, the family will use Rosenthal china that Zaidy Victor and Bubby Bella, Michele’s grandparents, bought and took with them as they escaped with their lives after the war. Last year, Mendel and Leah lugged two knapsacks filled with dishes, bubble-wrapped, on the long flight, just ahead of the pandemic shutdown. (Another stash of dishes is waiting on Long Island for when flying is more feasible.) Sometimes, the dinnerware and familiar furniture are part of the seder. I never attended one as a kid with many Jewish friends in Queens, although I must have gone to half a dozen bar mitzvahs. When I covered religion for the NYT, I was invited to the warm, welcoming Upper West Side apartment of Rabbi Wolfe and Jackie Kelman, our friends and teachers.  An aunt's dinnerware, when the coast is clear An aunt's dinnerware, when the coast is clear The tables radiated with people from all over – a Japanese couple one year, a Caribbean couple one year, lapsed Jews, observant Jews, and Christians like us. One year, as guests were asked to sing, I delightedly recalled a Hebrew hymn I learned in the chorus at Jamaica High School; the next year I sang a bit of “Amazing Grace.” Many of the celebrants stressed the Passover concern for the stranger, the marginal, people who suffer. Only recently have I made the connection with Easter dinners when I was young, when my mother cooked the specialties of England, where she was born – roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, mint sauce. There was one tradition, if you will: at Easter, at Thanksgiving, at Christmas, a family often dropped in for dessert -- a father and his three children. Missing was the wife, my mother’s dear friend at Jamaica High; she had died young, and this good and sad man was raising their children. I don’t recall us ever talking about the absent friend during that visit, but she was there. In every civilization, the stranger is respected. My wife talks glowingly about meals served her in humble homes in India; my sister Janet and I were recently invited to visit (with lavish snacks) our family home in Queens, by the accomplished Muslim family that now lives there. My wife and I are still holed up, waiting for the blessed vaccines to take hold, waiting for “normal times” to return. All three of our children have dinnerware with family histories, and Marianne brings out the Limoges china given us by her Aunt Emma, a sweet old lady who had no children. (Well, except for a dinner on Christmas Eve, years ago, when we entertained Jewish friends who kept Kosher, and Marianne used glass and paper plates. Warm memories.) It makes me happy to think about the Horowitz family celebrating their seder with china that once belonged to their elders – a ritual of continuity, a celebration of survival. Bad enough that epic ballplayers are passing. Now it’s Toots. Our oldest, Laura, caught him two summers ago in Albany, the gateway to Almost Heaven, Adirondacks. “Bucket list item for me,” Laura typed Sunday from Upstate, when we heard about the passing of Toots Hibbert, age 77, the lead singer of Toots and the Maytals, classic reggae group, which was around for, oh, forever. I remember when I became aware of Toots. I was a regular listener on WNEW-FM, since it became the great pioneer rock station in 1967. For years, Dave Herman had the morning drive-time show that ended at 10 AM. One morning he said he would have, live in the studio, the great Toots Hibbert. And kept telling us, as the final hour ticked away. Finally, about 9:50 or so, Toots arrived in the studio. Only thing was, his mind and his voice had not yet arrived. Brother Dave tried to engage him on why he was in New York, where he was playing, plug his latest album, etc. etc., but Toots emitted only monosyllables. About 9:58, Toots started talking…and talking….a deep-throated but lilting monologue, right up to the signoff music the universal signal that the station is about to move on to news weather, the next host. Ultimately, click, the engineer cut Toots off, mid-sentence. “I think I like this guy,” I said, and I went out and found his cassette (yes, it was that far back), “Funky Kingston,” with songs like “Pressure Drop” and ”Time Tough,” plus the adaptation of John Denver’s song, “Country Roads,” but in the Maytals’ version it becomes “Almost Heaven, West Jamaica.” I loved it, just as much as I love the ruined mountains of Appalachia, and I loved Toots from afar. Never saw him, but the cassette endured. Laura says she has replaced her copy two or three times. Toots had a sound – I’ll let the pop music critics explain. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/12/arts/music/toots-hibbert-dead.html He wasn’t Bob Marley, whom I regard as musical divinity, but Toots’ earthly voice and rhythm told of joy and pain, good times and bad times. And made you want to move. I never caught him live and never will, but Laura and Diane drove down to the Capitol Region in August of 2018 to catch Toots. “Toots. Free concert. Diverse Albany crowd. Weather,” Laura messaged on Sunday morning as we commiserated.  Laura wrote: The band had driven all the way from California and barely got there on time. The band played Toots in for a good 5-10 minutes before he finally walked on from the back. Then. It was ON. He was older and somewhat stiff but still totally commanding and powerful and totally adept at working the crowd. I typed, “Got any photos?” and the cellphone quivered and hummed and buzzed. She added: "One of the great nights out. Ever."   This baseball season may turn out to be a colossal gamble, but I am enjoying the cardboard fans in the stands, particularly these folks in Oakland. I think I would like sitting with them in the stands on a warm East Bay afternoon. Fact is, I miss human company, as my wife and I hunker down waiting for Jan. 21, when intelligent adults take back the country. I miss my kids and I miss my grandkids. This elbow contact on our deck, when the weather cooperates, is not the same as hugging my family, or sitting indoors, or, imagine this, going out...somewhere. Then I remembered the three people who inhabit our storage room in the basement -- present from our dear creative friend Rachel, who had these made up for her job, back a few years, when we all were younger. (Let me add this: I have an Irish passport, courtesy of my maternal grandmother from Waterford, and I am very proud of it. My identification with the UK has way more to do with the National Theatre and Portrait Gallery than the royals, When I see these one-inch likenesses, I think of our friend Rachel, speaking up for Palestinians at a Seder on West End Avenue. For all that, Queen Elizabeth II fits right in with our unused dining room. As I walk through, I find myself singing along with Paul: Her majesty's a pretty nice girl, But she doesn't have a lot to say. ... Irreverent, I know. Fact is, the Queen is one of the stable elders in the world today. What with Trump and Pence and Pompeo and Barr and that bunch, Americans are in no position to snicker at royals. Welcome upstairs for a while, Your Majesty. Let's sit and have a cuppa.  Did Charles ever look this militant on his best day? But he's doing a good job, guarding my wife's studio day and night. Plus, as I walk past and give him a snappy salute from my ROTC days, I remember that Emma Thompson is a good friend of his, and always speaks well of him when she is interviewed. Whatever is good for Emma Thompson is good for me. Until an adult leader takes control of the Covid virus and puts an end to this social-distancing, good old Charles serves a purpose,guarding the house, waiting, waiting, waiting... It's true, Princess Diana looks a little stiff in our living room, but let me tell you about the time she and her two frisky little boys were guests in the Royal Box at the old Wimbledon, which was directly next to the open press area. Needless to say, we were all eyes for her, and the Beastie Boys of the British press were coming up with plummy accents and snide comments. And while we tried to covertly look at Diana, I noticed that her eyes, like lasers, were scanning the doings around her. She was looking at us! Curiously, like, who are those people, and what do they do, and are they having a good time? She was out and about, not at all rigid, clutching her purse, like in this cardboard version. Her eyes saw all.

So, welcome to our living room. May I take your coat? please, have a seat. May we offer you a glass of wine? What do you think of Brexit? How do you like Boris Johnson? We hear you are working to to sort out this Covid mess. We apologize for our buffoon. My wife's been working on our family trees: her roots in Lancashire include William the Conqueror; my middle name is the same as your family name --Spencer, from my mom, born in England. * * * We still miss our family and friends, but in a weird way, thanks to baseball, our living room lives again. Thanks to our friend Rachel for these vital presences. Some colleges have their priorities straight during this time of Covid-19.

Four schools I already admired – Bowdoin, Morehouse, Sarah Lawrence and Swarthmore -- showed their values in recent days by cancelling all or part of their autumn athletic programs, so they could concentrate on education. Imagine. These schools do not exist to present extravaganza football games every Saturday during the fall semester, for the benefit of boosters and TV networks, to churn up money to keep the whole monstrosity going. However: each decision to cancel caused terrible pain to the people who mattered the most – the student-athletes who will not get to compete this fall, practice with their teammates, perform in front of vociferous family members and loyal fans. You cannot red-shirt a virus-cancelled season, say “come back for a fifth year.” Plus, these student-athletes have futures, although the 2020 fall season will not be part of them. We take it personally in our family. Our grand-daughter, Lulu Wilson, is a loyal member of the Swarthmore women’s soccer team that reached the Division III tournament in her first two seasons. She played very little in her first year due to an eye condition following a concussion, but she played some in her sophomore year - - and every time I checked in on her she raved about her teammates and her coaches and the practices and the togetherness. In between, she pursues a pre-med program, having already spent compelling days in hospitals, gowned up, watching the routines and even the operations. She is all in. When Swarthmore cancelled all fall sports, I checked in on Lulu and asked how she felt about the decision. “Honestly, I think it is smart of Swat,” she texted, using the nickname for the school, “and I admire that they are trying to keep us safe and move our country towards an end. “I think it would be ignorant of them to let us play,” she added. “I look at these big schools going back full-force and I worry that these kids are going to cause outbreaks and keep the pandemic going for the country as a whole. "So I respect what they did,” she said, adding her opinion that “online learning is not the same as a true Swat experience.” Now she is in mourning for what will always be lost – an autumn of practices in the drizzle and gathering darkness, the bus rides around the Northeast, and the identifiable voices of parents who travel from around the country to cheer for Swat. (Intro to Div III: in 2018, after Swarthmore lost to Middlebury in the Round of 16 up in Vermont, on the long bus ride back to Philadelphia, many of the players started studying for final exams coming up, she told me then.) “These four years are really special for us to be together as a team so this time apart will be hard," Lulu said Thursday. "We will have to find ways to stick together and find the positives in this situation.” Swarthmore student-athletes are not alone. I had a premonition a few days ago when I read that Bowdoin had cancelled fall sports. My wife and I have fallen in love with the college in Brunswick, Maine, from visiting the area in recent years, and we always find time to visit the jewel of an art museum on the campus. I also admired the decision by Morehouse in Atlanta to cancel football this year. I have become a fan of Morehouse over the years because of alumni like Martin Luther King, Jr., Donn Clendenon of the 1969 Mets, my Brooklyn hero Spike Lee, and Terrance McKnight, knowledgeable host of a nightly show on WQXR-FM, the classical station in New York. And Sarah Lawrence, in Bronxville, just above New York, is where we were lucky enough to send our two daughters, who gained great educations and eclectic talented friends. The other day, SLC cancelled all autumn sports. All schools are wrestling with terrible choices in this time of the virus. There are no easy answers, but these four admirable schools examined their values and realized sports were expendable – nevertheless, leaving a gigantic loss for a young student who loves her sport, her team, and also her education. ### For many years, Marianne painted in the midnight hours, when the kids were asleep and I was on the road somewhere. After a few hours of sleep, she got up and made school lunches and checked her lesson plans and drove off to teach art.

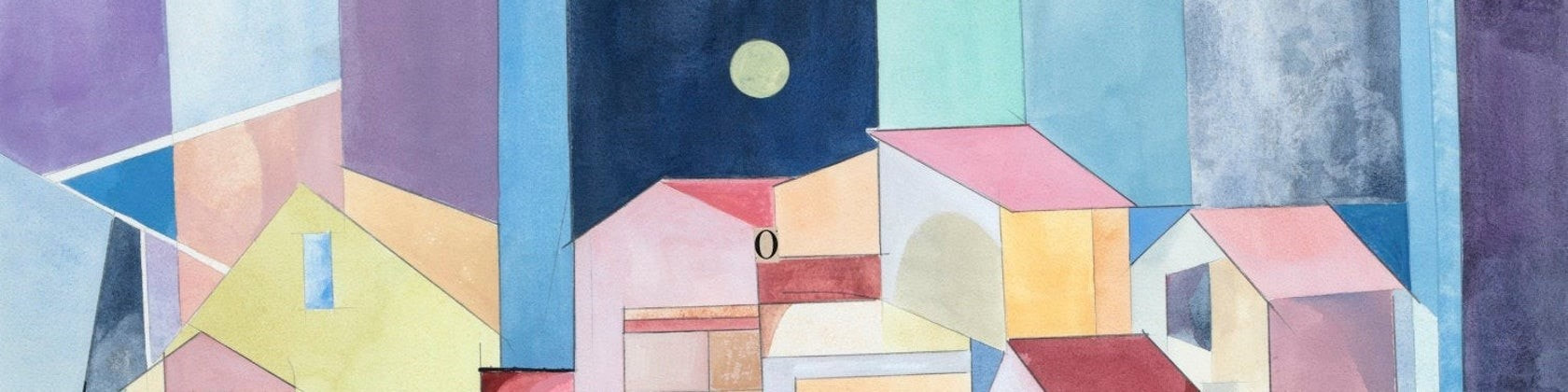

At some point she produced this large painting, which wound up in a gallery in Manhattan, and then in friends’ apartment on the Upper East Side. But now those friends are downsizing, and no longer have room for the painting, so they graciously offered it back to the artist. In the middle of a pandemic, with no station wagon anymore, we did not see retrieving it and squeezing it into our house, already crammed with books and art and kitchen utensils. Marianne mentioned her dilemma to our West Side friends, who are redecorating their apartment in the 50s. They know her work, and were interested, but the painting had been wrapped, and was sequestered in the basement of the East Side building. So they accepted it, sight unseen. Then came moving day, part of the daily buzz of the city, good times or bad times -- folks clutching modest bags of clothing on the subway, other folks engaging gigantic moving vans that block side streets, out-of-town children of privilege who come clumping down the elevated train stairs with one wheeled suitcase in an “emerging” neighborhood, getting dirty looks from ladies in the local peluqeria whose rents are about to double. (I witnessed that in Bushwick two years ago.) Now our friends were joining the sidewalk shuffle, taking 45 minutes to walk across town, spotting “dog runners and dog strollers in the park, empty buses plying Fifth, a fit couple racing up and down the Met Museum’s steps. The ‘Ancient Playground” at 85th and Fifth still temporarily closed,’” as the lady half of the couple wrote. I had warned that if they tried to carry the painting across town, one of those classic crosswinds that scream out of a side street could pick them up, clutching the painting, and deposit them in Oz, or New Jersey. But it did not come to that, because when the East Side porter delivered the 6-by 4-foot package near the front door, they realized it was so sturdy that blithely carrying it across town – for fun, for exercise – was out of the question. Now began the quest for wheels. They tried shoe-horning it into a city taxi, but it was four inches too long, so they tipped the driver for his effort, and waved farewell. The super helped them carry it to a busy corner and left them to their adventure. They hailed two panel trucks and tried to cajole the drivers into making an excursion, but both apologized for being busy. A plumber parked nearby offered to help but needed an hour to set up his crew. Tired of standing on the corner propping up a large painting, they called a messenger service, New York Minute, which promised to drop it at their building, as they took a taxi back home. An hour later, the painting arrived and they set it on the terrace for a few hours to give germs time to die. They still had not seen the painting that had occupied several weeks of logistics that could have sent a spaceship to a far-off docking station. (Did I mention that Marianne, in her other life as matchmaker, a/k/a the shiksa shadchen, had matched these two friends, not so long ago?) “Unwrapped, it was love at first sight. It’s Marianne’s Geometric Period, mixed media watercolor and oil,” our friend reported. “It miraculously fit on the pre-existing hooks opposite our bed.” They took a photo – the miracle of the smartphone—and beamed it to Marianne, who immediately recognized it from the period, decades ago, when she found a makeshift table that could accommodate larger canvases. She has sold around 250 paintings, some now dispersed around the world. She may not recall the year or the circumstances of each painting, but she recognizes each painting, remembers the creation. She has won awards in juried shows, has placed her work in slide form or real-life form, in Manhattan galleries, has received respectful “keep-painting” receptions from major galleries, some of them part of the art hustle of recent decades, no names mentioned. It all came back to her, including the review in NYT’s Long Island Section, by critic Phyllis Braff: One feels and imagines the aura of the Grand Canyon, Notre Dame, a night sky, a fall landscape or a cemetery in visions that are executed through rather innovative manipulations of small squares made vibrant with mottled, transparent watercolor tones. Color selections that tend to be symbolic, and exacting schemes of dispersing the painted units, are both important in carrying the message. This painting, part of Marianne’s most active period, is now hanging in the bedroom of a fashionable apartment, home to many soirees with art-conscious New Yorkers. But the main reward came when the lady wrote: The painting is now the last the last thing we see at night, and the first thing we see in the morning. Joy. Marianne’s painting has made the daunting crosstown trek from the East Side to the West Side. Its journey has also brought us joy. * * * The review in the NYT by critic Phyllis Braff: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/09/nyregion/art-unexpected-messages-in-geomettic-form.html?searchResultPosition=1 It's amazing what you can find on line, from people you don't even know, who are updating ancestry information. New information pops up, virtually day by day.

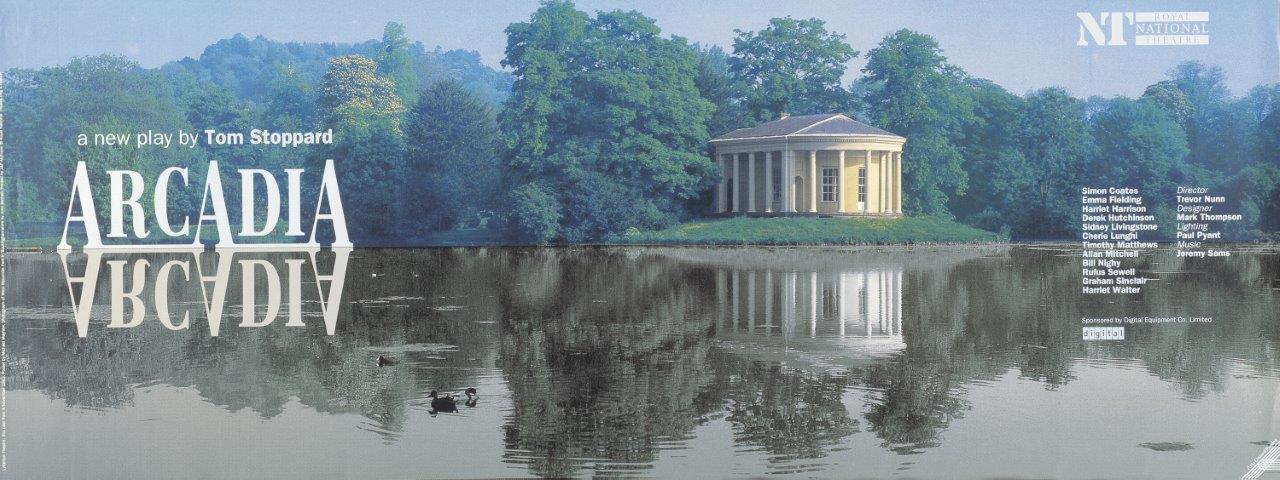

My wife and I were discussing her ongoing genealogy research of her maternal ancestors in Lancashire, England – so many relatives with the same names, from century to century. People with the same first and last names pop up in Manchester....or Liverpool....or Rhode Island....or Baltimore....or Kentucky.....or Australia....and some of them even back to England. She also researched my mother’s ancestry, in the same region -- centuries of women named Mary and Jane and Elizabeth (right out of the 16th Century history books) plus men named John and James and George. No direct links between families, at least not yet. We agreed there could be a play about the overlapping of the centuries – when suddenly we remembered that just such a play has already been written. “Stoppard!” one said. “Arcadia!” the other said. I refreshed my memory about "Arcadia," and the first thing I noticed was that the playwright, Tom Stoppard (Born Tomás Straüssler on July 3, 1937 in Zlín, Czechoslovakia) is having a birthday soon. Happy birthday, with thanks for one of the most beautiful evenings we have ever spent in the theater. It was July of 1993, and I was not scheduled to write at Wimbledon that day, so I started to duck out of the press tribune around 5, only to hear the cutting tones of my beloved colleague, Robin Finn, alerting the entire press crew: “So, Giorgio, the Missus has theater tickets tonight, huh?” Well, yes. Marianne had picked up tickets for the Stoppard play at the National Theatre on the South Bank, our favorite place in London, or maybe the world. Very often, she would see two plays in one day. This night we watched a play about a country estate in Derbyshire in 1809, where a man is tutoring his precocious charge, just entering her teens. The plot is complicated – Stoppard’s always are – but the main theme is about the maintenance of the mansion; to change or not to change? The action shifts to 1990 or so, when other humans are discussing the very same country estate. (Makes you think there just might always be an England, despite its “leaders.”) The centuries rock against each other like tectonic plates but the twains do not meet until – spoiler alert – the very last scene, when the two generations mingle on the stage. Stoppard can be highly intellectual and abstract, but suddenly my eyes were gushing, tears from nowhere. This is the best thing the theater can do – bring you to your knees, in emotion. My fine drama teachers at Hofstra taught us about “catharsis” – from the Greek, the cleansing, the purging. “Arcadia” made us think and feel deeply. In 2009, The Independent asked if Arcadia was the “greatest play of our age.” One review described “Arcadia” as “a serious comedy about science, sex and landscape gardening.” I also remember a murder mystery and physics mixed in. My best to you, sir. Perhaps you are writing? * * * More about “Arcadia:” https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-dance/features/is-tom-stoppards-arcadia-the-greatest-play-of-our-age-1688852.html https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/1993/apr/18/features.review7 https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/tom-stoppard In 1869, a group of civic-minded women opened a home for older people, on the island of Manhattan. The leader was Hannah Newland Chapin, wife of Edwin Chapin, a noted Universalist minister in New York. The motto of the Chapin Home was: “What is your need‚ not your creed.” In 1910, the home was moved to the glacial spine of Queens, where it remains to this day. http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2012/01/lost-chapin-home-for-aged-and-infirm.html My mother, May Spencer, wrote about the Chapin Home as a reporter, and later Society Editor, of the Long Island Press in Queens. The home was on familiar turf -- right down the block from the beautiful new Jamaica High School, where my mom had been in the first group of students in 1927. The Chapin Home obviously made an impression on our mom. When we began to suggest that she needed more care than she was getting, alone, in the big old house where she had lived since 1925, she was having none of it. However, she allowed as how she had found the Chapin Home to be a nice place when she was a young reporter. And when it became necessary, our mom spent most of the last years of her life in the Chapin Home. For the past month, the Chapin Home has been celebrating its 150th anniversary. How many institutions last that long? Well, in that same year, with the wounds of the Civil War so visible, when these civic-minded woman built a rest home, the American Museum of Natural History was founded in New York City; the “golden spike" was driven in Utah, completing the first transcontinental railroad; the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first fully professional baseball team. (Jesse James robbed his first bank that year, Happy anniversary, Jesse.) And the Chapin Home is still going strong. I heard about a sesquicentennial party last Friday and accepted an invitation. But first, I consulted my siblings about their memories of Mom in Chapin. We all agreed that Mom’s formidable intelligence and strong will had given the staff a good challenge. One of the caretakers – I believe with a lilting Trinidadian accent – had nicknamed Mom “City Hall.” You know – you can’t tell City Hall anything. My sister Liz recalled how the staff would make sure Mom was dressed for a ride in her wheelchair down the block to Jamaica High and how Mom would sit in Goose Pond, across the street, and tell about her days at Jamaica. Liz’s husband, Rich, has fond memories of the weekly Catholic Mass there, and the musical entertainment – and how he would dance with some of the “showgirls” who lived at Chapin. My sister Jane recalled how “staff members were so welcoming, and helpful,” and how other residents became Mom's friends - and ours. “What a blessing it was for her to spend her final years there,” Jane said. My brother Chris remembered how the staff “showed loving humanity,” particularly a caretaker named Delva (still at Chapin) who “called me several times in Mom's early days at Chapin, either telling me what was most disturbing Mom or placing me in telephone contact with her.” And my wife recalled how the staff made it easy for her to sit with my mom in her final weeks, and play opera on the CDs, and how other residents would visit the room, for the music as well as to give support. With these memories fresh in my notebook, I went back to Chapin last Friday and met Kathy Ferrara, the director of activities‚ volunteers and spiritual care, a friendly face from Mom’s time. I also ran into Janet Unger, the former administrator, now retired, and Jennifer McManamin, now the chief administrator. I felt great energy and purpose from all the staff. Nearly 17 years later, the main hall, under a bright skylight, seemed like home -- full of residents, many in wheelchairs, or with walkers, the clientele as diverse as Queens itself. After lovely music by a harpist, Chapin honored seven residents as centenarians – 100 years or older – and three others who are 99, including Frances Cottone, who wore her red Marines cap, having served stateside during World War Two. (Local Fox News, Channel 5, did a nice feature on the centenarians) https://www.chapinhome.org/news After a few short talks, the staff distributed birthday cake, while a pretty singer entertained with American standards – Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, plus Tom Jobim’s “Corcovado,” in Portuguese. I later looked up the singer, Hilary Gardner, and discovered she is very active in jazz circles, in New York, Europe and elsewhere – and has a very interesting web site. https://www.hilarygardner.com/about Some residents smiled and applauded the music; others just took it in. A few ladies danced in place, or with a few young male attendants, and Kathy Ferrara, alert and smiling, just as I remembered her, danced with several women. (She even got me up on my feet for a few minutes for my vague approximation of the lindy.) Visiting my mom for five years demystified aging for me. On my return, I remembered how hard the staff worked, how they kept the Chapin Home clean and positive. I have no illusions about the daily routine back in the residential wing -- the care needed by the ill and the elderly, the hard work, the constant upbeat attitude.

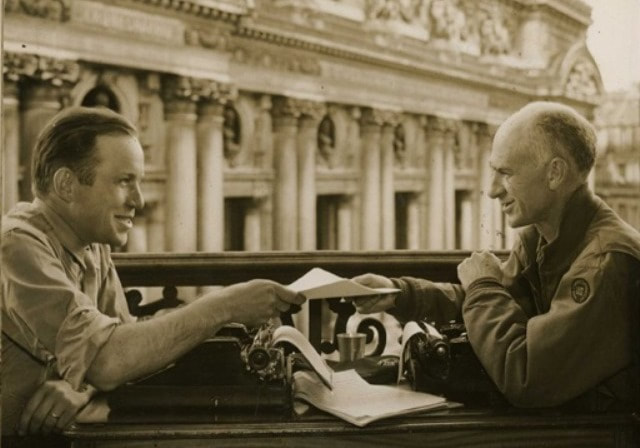

Memories of my mom flooded back: sharing her mid-day meal, looking out her window at Joe Austin Park (named for an epic youth coach in Jamaica, an honor bestowed by one of his star athletes, named Mario Cuomo.) Coming back, years later, I felt very much at home.  Western PA: Halfway between NY and IL, couple crossed Roberto Clemente Bridge to catch a ball game. Western PA: Halfway between NY and IL, couple crossed Roberto Clemente Bridge to catch a ball game. After months of home-repair madness, it was a treat to spend a quiet Easter at home. Then the pinging began on the phone. I was puttering around, trying to restore order from the detritus of repairs. Marianne made a delicious vegetable-and-chicken soup.  New England: Easter Egg Atelier checks in WNYC-FM was playing weekly jazz show. Two versions of "April in Paris," first by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, then by Count Basie ("one more -- once") Homage to the stricken Cathedral de Notre-Dame. Mel Torme. Bob Dylan. An American blues singer acing a song. Not American, my wife said. It's Adele. As always, she was right.  Anna Duchene, Brussels, 1954. Anna Duchene, Brussels, 1954. Hal Boyle’s columns were big wherever the Associated Press was used. He was Everyman, from Kansas City, writing for Middle America, with no political bias and plenty of heart. I knew Boyle, from bowling in the Associated Press league when I was a 16-year-old copyboy. He was a jovial man whom I recall with cigar and perhaps a beer, laughing easily with everybody. He had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1945 – for his coverage of the European war -- but you would never know it. https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/harold-v-hal-boyle Now, as a recovering columnist, I am reading Hal Boyle’s columns. In 1954, he visited my Irish-born grandaunt in Brussels and wrote about the atomization of her family from World War II. (I recently came upon my mother’s cache of photos and clippings of her lost Belgian-Irish relatives.) Decades later, Hal Boyle holds up in hard-cover form; very few columnists do -- Mike Royko, Jimmy Breslin, a few story-tellers, writing about the human condition. Like the best journalists, Boyle has a fine eye for details – the bullet hole in Madame Duchene’s front doorway -- from the day a Scottish soldier she had been hiding bolted from the Gestapo, and was gunned down in the street. (He lived to old age but Madame Duchene’s daughter, Florence, and her son, Leopold, did not.) I cannot access Boyle’s column on line, but I wrote about that family in 2006: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/09/sports/soccer/09vecsey.html Boyle paints a portrait of the grandaunt I never met. On the 10th anniversary of following the Allies into Europe, he spent a few hours at her home – get this -- 7, rue Sans-Souci. (Street Without Care) Again, like the best journalists, Boyle is there to observe, to ask questions. His compassion for the old lady with her memories and her medals, surely has roots in his mother’s childhood in poverty-ridden Ireland. I never finished his collection – the aptly-named “Help, Help! Another Day!” – from a poem by Emily Dickinson – but now I am enjoying his changes of pace: communing with the graves of men who died on the Normandy killing beach, or staying in a camp deep in the Catskills, listening to the sounds of night. Perhaps his most poignant column came from defying the third or fourth rule of journalism – never succumb to the cheap device of quoting taxi drivers. But Boyle happened to ride in the cab of a philosopher who was mourning a beloved wife who had died years earlier. The man advised Boyle to cherish his own wife, and life itself, and Boyle was wise and talented enough to make a column out of his encounter. (Boyle’s own wife would die young, and he would follow, from a heart attack, at only 63.) Many great journalists are full of themselves, to the point of grimness, but Boyle was jolly, in a melancholy Irish way. He was as much at home in the camaraderie of a beer frame as he had been with the sights and sounds of combat. One thing I just learned from skimming his columns: his own meter was always running. I am convinced: what I am about to tell you is no coincidence: At that bowling alley – Beacon Lanes, 76th and Amsterdam, second floor – the coat-check was run by a highly loquacious and secure black man, who seemed to have the word “autodidact” glowing proudly like theater lights on his forehead. The man liked to chat about the books and poems he had read – most notably “Thanatopsis,” by William Cullen Bryant, using the Greek word for “consideration of death.” At 16, I looked forward to my weekly chat with the brother. Now, 63 years later, I pick up Hal Boyle’s collection. His latest column is from Jan. 9, 1964, called “Nostalgia Is a Medicine to Cure the Blues,” with one-line observations about things you don’t see much anymore. One of them was: “Anybody with a claim to culture could prove it by reciting aloud the concluding lines of William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis.” This means, to me, without a doubt, that Hal Boyle, Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist of the Associated Press, had been chatting with the same vibrant coat-check man at the Beacon Lanes in the season of 1955-56. With that discovery, I feel a great kinship with the man who visited my grandaunt in war-ravaged Brussels. I wish I had read more of Hal Boyle, had asked more questions, back in the day. But I did bowl with him. Our granddaughter Anjali came over Sunday to pick up some cookie utensils.

She's driving now. Having a very good year. Marianne took out her assortment of cookie-decorator tools from holidays past. The two of them huddled over a kitchen table, trying to put together one gadget for spreading icing. There was Christmas music on WQXR-FM. I stood and watched this very sweet moment as.two artistic and orderly minds collaborated to get it together. I thought about our holidays when our children were young; I thought about the way my parents managed to have a clutter of presents for five children. How did they do that? What a blessing to have two of our three children in town with us -- one grandchild in a school concert the other night, another popping over since she earned her driver's license, Grandmother and granddaughter smiled and agreed. All systems go. Anjali tootled home to work with her parents on their cookies. A few hours later this photo came pinging onto the smartphone. Tomorrow we get to sample. From our family to all our friends, including those who glance at this little therapy web site: Be Well. Happy Holidays. So many loyalties, bouncing around on Saturday in the forlorn USA.

We all have our ethnic ties, our favorite superstars, the teams that caught our fancy, our memories of World Cups past. At a family gathering, one bloke from Deepest Pennsylvania wore a t-shirt honoring home-boy Christian Pulisic, who just might be the next Ryan Giggs, the next George Weah. (You know why.) One wannabe scugnizzo in our group wore an Italia 2006 t-shirt, in honor of the Year of the Head Butt. It's all we had. Then all of a sudden in the second match, there emerged a deep and nearly universal feel for the homeland -- well, somebody's homeland. Croatia! Yes, I was surrounded by people rooting for Modric, for Raketic, for the hamstrung keeper. Because I am a little slow, I needed an explanation. I couldn't muster up any hard feelings for Russia, having spent three weeks in Moscow during the Goodwill Games of 1986 and feeling the warmth and passion and generosity and culture and history of the people. It's not the people, I was told. It's Putin. Or more specifically, his new best friend. A cheer for Croatia was a thumbs-down for Trump and his man-crush on the swashbuckling bare-chested heckuva guy from Russia. So here are my reactions to the last two quarterfinal matches: England 2, Sweden 0 The team that kept Italy out -- no hard feelings -- and then beat South Korea, Mexico and Switzerland in the World Cup -- did not have the disruptive force against England. England, disparaged by its own fans for fielding many second-raters from Premiership squads, does have Harry Kane, the hardest-working man in show business (homage to the late James Brown.) Kane is more of a constant threat than many of the superstars now resting at beaches and cottages around the world. Harry Maguire seems able to stick his noggin into the scrum at the right moment, the right angle. It's fun to watch a squad blend on center stage. Croatia 2, Russia 2 (Croatia, 4-3, Penalty Kicks) Russia went as far as it could, on the stimulus of being the home team.When the players encouraged the home crowd to cheer louder, they were acknowledging the lift they got from the noise. Never mind the jokes about Putin fixing the World Cup. There was no poison smeared on umbrella tips or somebody's home doorknob. (That we know of.) Credit the players -- and the fans, who reminded me of emotional people I met in my three weeks there. Croatia's play is a tribute to the ability of small nations (Belgium included) that can nurture skilled and superior athletes and then blend them when they regroup for national-team play. I am increasingly a fan of Luka Modric, the quiet, roaming general who plays back, then arranges the pattern, and often takes the shot himself. He grows on you. On to the semifinals. I assume Trump harbors grudges against all four survivors, for something. Uncle Harold took us on great drives around coastal Maine – the beaches, the woods, the little towns.

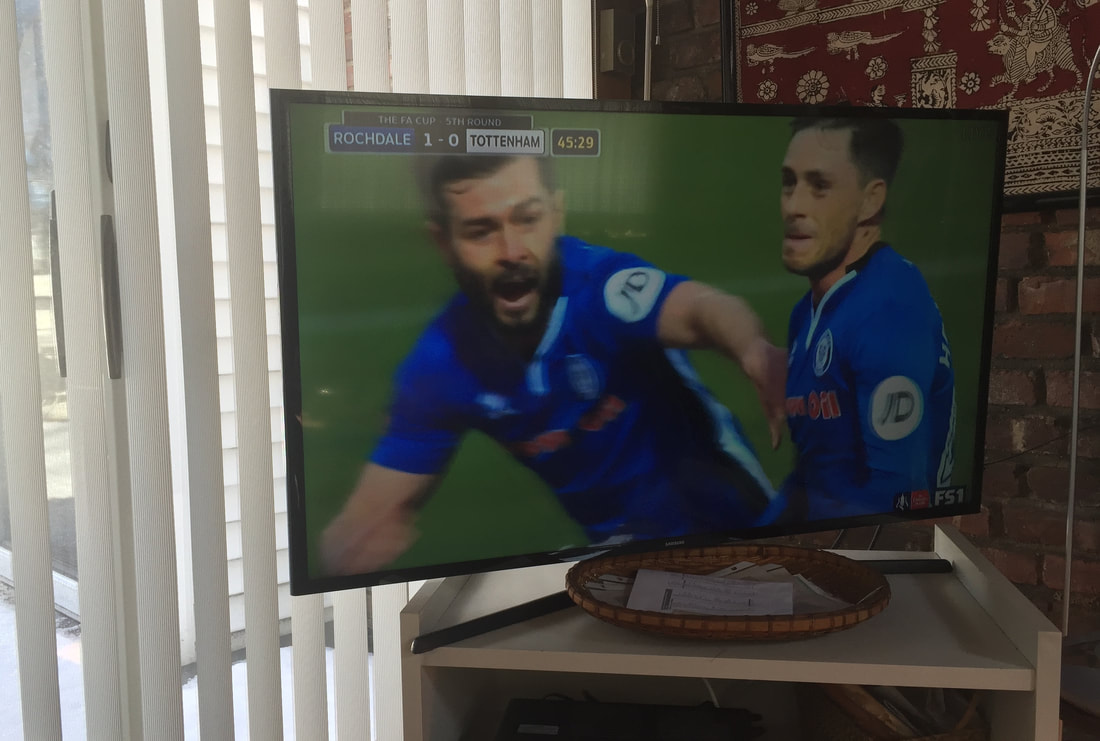

The tours invariably ended near Oak Grove Cemetery in his home town of Bath. “Why don’t we just drive in,” he would suggest. We would park on the narrow lane and walk to the single tombstone for his wife Barbara and their son Roger. Harold’s name was waiting for the date of his death. Roger had died in a car accident near home, after surviving a bullet and malaria in Vietnam. Barbara had lived a long and active life, caring for others, although wracked by bone disease and later diabetes. Harold often talked about her in the present tense, as in “Barbara and I take this road to Boothbay Harbor for the fried fish.” My wife, his niece, and I started visiting Harold Grundy after Barbara passed in 2014. We fell in love with that part of Maine, and at my own advanced age I found myself a new hero, as he casually told stories about surviving combat in the Pacific and building electronic surveillance outposts in Greenland and Guantánamo Bay. But he was wearing down, and it took a village of loved ones to usher him through pain and confusion before he passed on Jan. 4. People in cold climates cannot bury their dead in mid-winter. Harold, stubborn by nature, modest from his Quaker background, precise from his construction career, specified no ceremony, no fuss, for his burial. His two faithful surrogate children, Ace and Cookie, now living in Arizona and Connecticut, arranged for a no-frills burial on May 11. Eric came in from Florida. My wife and I were asked to represent the family, scattered and getting on in years. A few locals heard about the burial, and then a few others, and they got to the cemetery, some using walkers and canes to reach the casket, with the American flag neatly folded on top. The sun was bright, the breeze was chilly, and the funeral director read a few prayers -- as quick and simple as Harold had mandated. A very fit military guy in a red flannel shirt, who had worked with Harold at the surveillance base in Cutler, Me., stood at attention and whispered to me: “Best man I ever met.” Later, eight of us met at a tavern alongside the glistening Kennebec River. We toasted the family, and told a few stories. Ace told how Barbara and Harold used to take him along on so many family outings when he was a kid. And Ace told how Harold approached the mathematical challenge of building basement stairs: “He wasn’t telling me what to do. He was teaching me.” People smiled as they recalled how Harold always had fresh pies and pungent chowders on the stove for company. My wife, the oldest of her generation, remembered a Christmas right after the war, when three young couples were sharing a small house on the Connecticut shore, and how she witnessed Uncle Harold using a tiny saw on a wooden bowl. On Christmas morning, she found a beautiful bed for her doll’s house. Harold always made things. He and Barbara used to peddle his home-made toys at flea markets in the region, and later his friend Eric made a thriving web business out of wooden objects. Nobody wanted to leave the lunch. Cookie, so loyal and capable, who did the paperwork for Barbara and Harold for decades, proposed that our little community meet again next year. We went our separate ways, knowing that Harold was up on the hill at Oak Grove Cemetery, with Barbara and Roger. * * * I’ve written about Harold and Barbara and Maine: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/farewell-to-harold-grundy-of-the-greatest-generation https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/sometimes-a-good-idea-actually-works-out https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/dredging-the-river-in-1941-for-a-destroyer-in-2016 The first thing to note is that my wife has been studying a grandfather’s genealogy in recent years, producing notebooks packed with Grundys and Cleggs and Schofields from towns around Manchester – Bury, Oldham, Salford and Rochdale.

The second point is that my wife has more tolerance for soccer (the real football) than any other sport – partially because the lads are fit and usually get their work done on time. Through friends, she attended the best individual World Cup final ever – Zidane’s masterpiece over Brazil, in great position to see his two headers. On Sunday I said Rochdale was playing Tottenham in an FA Cup fifth-round match – on the tube, in our warm den. She had never heard of the Rochdale team but did know about Tottenham from Joe Scarborough’s lovely recent documentary about the North London darby – Tottenham vs. Arsenal: suspected hooligans, tattoo artists, rabid Tottenham owner, rabid Piers Morgan, Arsenal fan. As the match began, I chattered about the romance of the FA Cup – the open tournament from late summer to following spring which allows modest clubs to take on higher-ranked teams, with a glorious history of upsets and scares. In 2003 we were in London partially for me to write a piece for the Times about a squad “with a tree surgeon (with chain-saw scars to prove it) along with truck drivers and teachers,” along with a couple of actual professionals, from lowly Farnborough, down south, somehow reaching a third-round FA Cup match at Arsenal’s beloved old stadium at Highbury, and how the visitors even managed a goal against Arsenal’s irregulars in a 5-1 loss on a lovely Saturday morning. My tutorial over, we settled in to watch a fit and eager squad from Rochdale play the Tottenham irregulars at a modest 10,000-place field, now carrying the name of an oil company, but known to fans as Spotland. Why Spotland? I wondered. “Some of the old miners in my family lived in the Spotland section,” my wife said. Later she produced copious period maps of Rochdale from her stacks of notebooks. (FYI: The name Spotland comes from the River Spodden, which flows from the Pennine Hills.) The British broadcasters gave enough FA Cup details to overseas viewers – how Rochdale is in the third level, below Premiership and Championship, how a few lads have had a taste of the top rank, and a few young ones are still prospects. (I later learned that Rochdale, in 1960, was the first FA squad to hire a manager of color, Tony Collins. Since then, there has been exactly one more: Ruud Gullit.) For the first half hour, the home team jostled with the visitors on a new and treacherous field. Then came a glorious sign of fear and trembling from the Champions League side: wavy-haired Harry Kane, surprise marksman of recent years, began stretching on the sidelines. Rochdale would always have this: making Harry Kane, due for a day off, break a sweat, just in case. Who are those guys? I looked up the Rochdale roster: one striker was Stephen Humphrys, a 20-year-old from nearby Oldham, on loan from Fulham. “We’ve got some Humphrys in our family,”Marianne said, reminding me that some of them ran ships to Cuba and on to the colonies, carrying Lord-knows-what. She claimed Humphrys as a relative. The visitors began to pack the offense – enough of this foolishness – and we rooted for the home team to just hold them until the half. But the home boys showed enough professional skill to launch a counter-attack and have Ian Henderson, 33-year-old striker, who once mulled dental school, score in the 45th minute. Much yelling in our den – and not by me. My wife has been tracking people from Lancashire who worked in the mines or farmed, some migrating to Australia or New England and Virginia and Kentucky, or stayed home, adjusting to the Industrial Revolution, and then saw the factories sputter, and Nazi bombs destroy, and time march on, and Manchester City eat Manchester United’s fish-and-chips more often than not. (Her genealogy includes the name Scholes, from Salford. I told her about Paul Scholes, red-headed stalwart for Man U, most caps by any English national, who is from Salford, owns the sixth-tier Salford City club. No further connection detected.) In the second half, Tottenham did what it needed to do: tossed in three regulars, including Harry Kane, and tied the score. Then, after a world-level dive by Dele Alli, who is known for that stuff, Harry Kane coolly poked in the penalty in the 88th minute and Tottenham went ahead, 2-1. Moral victory? Not yet. In the 93rd minute, with one minute left in injury time, the last Rochdale sub, Steve Davies, in a desperation swarm, found a seam and fired into the corner for a 2-2 draw. Davies, we quickly learned, is a 30-year-old striker from Liverpool, who has played for some decent clubs. My wife said the family tree included people from Liverpool, and people named Davies. She adopted them all, the 14 lads who played, the fans packed together in the modest stands, as her instant rellies. The replay's gate receipts will carry Rochdale’s budget for the next few years, according to their jubilant, gray-bearded manager, Keith Hill, beneath his workingman’s cap. The Tottenham manager, Mauricio Pochettino, was more than gracious as he patted Hill’s gray beard and headed toward the team coach back to London. The weary Tottenham players, who endure dog years for huge salaries in their tri-level competitions, must now gear up for one more match, albeit it at home. Feb. 28: 10 AM, Eastern Time. The romance of the FA Cup endures. My wife’s uncle, Harold Grundy, passed early Thursday at the age of 95. He was an American hero – a carpenter who learned complex engineering skills, who kept Navy ships steaming in murderous waters in World War Two and later supervised the building of observation stations and nuclear plants. He was a survivor – of bombs in the Atlantic and Pacific, of winters in the Arctic, a wartime storm off England, a typhoon in the Pacific, and of life itself. His only child Roger came home wounded from Vietnam only to die from a car wreck on a Maine highway. His wife Barbara was wracked by diabetes -- and he took care of her, with the help of dear friends. Everybody knew him in Bath, Maine, Barbara’s home town. After Barbara died in 2014, Marianne recognized the need to visit her uncle once in a while. At 93, Harold would have thick, rich chowder on the stove and fresh fruit pies baking in the oven. Harold would take us on little outings from Bath – beaches and fish restaurants and back roads. He took us to coastal towns that looked like a setting for “Carousel” and fish-fry stands and old forts. He talked about Barbara in the present tense: “Sometimes Barbara and I drive up this road in the late afternoon.”

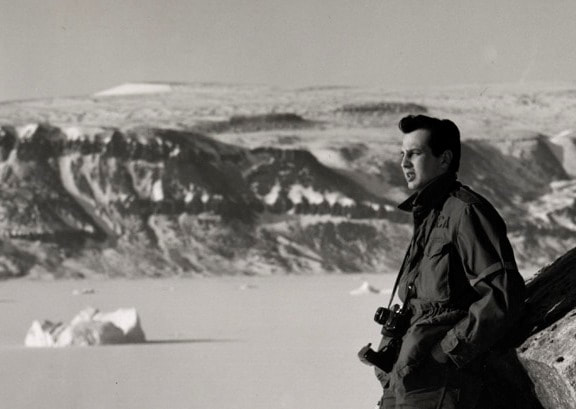

His education had ended in high school. He and his older brother left Connecticut in 1940 for a job dredging the Kennebec River to accommodate the large warships being built for what was coming. From his cottage alongside the river, he would tell us about rowing explosives into the middle of the river. In wartime, his acquired technical and engineering skills were essential to the military; he helped win one war and fight the Cold War. He was the last survivor who had served at observation posts in Greenland and Cutler, Me., and Guantanamo Bay, keeping an eye on our new best friends from Russia. However, because he was technically a civilian employee (ducking the same bombs as the military personnel), he was denied a pension by the U.S. government. Somehow, he was not bitter. Harold moved all over the world, building sensitive structures. Recently, we mentioned that one of our daughters lives near the nuclear plants at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. “Don’t worry,” Harold assured us, “I can tell you we made them double strong.” He had a Zelig-like way of being everywhere. He once chatted with a young senatorial candidate named John F. Kennedy in a train station in Boston; Winston Churchill popped out of No. 10 Downing Street and said hello to Harold and a few other tourists. One time we were driving near the coast and Harold casually mentioned he had helped build a house for Margaret Chase Smith when she was a senator. With her politician’s memory, she once recognized him when she got off a government plane at Cutler, and asked him to accompany her on her visit. People seemed to detect the civility and knowledge behind his humble bearing. He was so valuable to a construction company that they often flew Barbara to join him overseas, and they helped with her medical treatment. When Harold was home in Bath, between projects, he and Barbara, with her crippling diabetes, expanded a house on Washington St. He built houses and boats and docks and staircases for banks and chicken coops that were more handsome and sturdy-looking than some homes along the highway. Harold and Barbara started a little woodworking business – in their spare time, you understand – which has become a major business for a close friend. Harold and Barbara had a legion of dear friends who helped them: Cookie, Ace, Eric, Martha A, Martha B, Ann, Germaine, Diane, Rich and Suzanne, Bill, his nephew Dr. Paul, many caring medical people in the area, Kristi at the Plant Home, and people in shops and banks and drugstores, who fussed over them, in a real community. Two years ago, the Peary MacMillan Arctic Museum & Arctic Studies Center at nearby Bowdoin College held an exhibition of 193 photographs Harold took when he was based in Greenland. Harold’s family – including siblings in their 90s and late 80s – came in from New England and Florida for a reunion, in Harold’s most public moment. Harold came from hardy stock -- Quakers named Watrous and Crouch and Whipple who settled the eastern Connecticut coast and people named Grundy and Clegg and Schofield who thrived in Lancashire during the Industrial Revolution. But even these rugged folk wear down. Harold was fading the last time we saw him, on his 95th birthday in September. He had moved into a lovely retirement home, but his energy was gone and he could not enjoy the party. On Wednesday night, Cookie, a surrogate daughter to Harold and Barbara, who supervised their paperwork, was visiting from Connecticut, to be near him. Harold passed as a wintry storm roared up the coast. Come spring, Uncle Harold will be interred in the lovely hillside cemetery where he used to take us to visit Barbara and Roger. In recent weeks, as I thought about Harold and Barbara and Roger, my mind moved to a song about the release from pain – “Agate Hill,” by Alice Gerrard, recorded by the great Kathy Mattea. As I type this in the snowstorm, I think of Roger and Barbara and Harold together, building and cooking and fishing on some celestial version of coastal Maine, and I hear a line from the song: “Wild and free again, oh it will be as then.”  IN MEMORIAL, GERMAINE BOYNTON Harold often talked about his in-law Germaine who lived further up US 1. She invited us to lunch last spring and cooked a French-Canadian specialty and showed us the work and studios of hers and her daughter Diane, two formidable and artistic ladies. Germaine passed in hospice Saturday morning, two days after Harold. All through this long holiday period, I have been thinking of people who set an example for the rest of us.

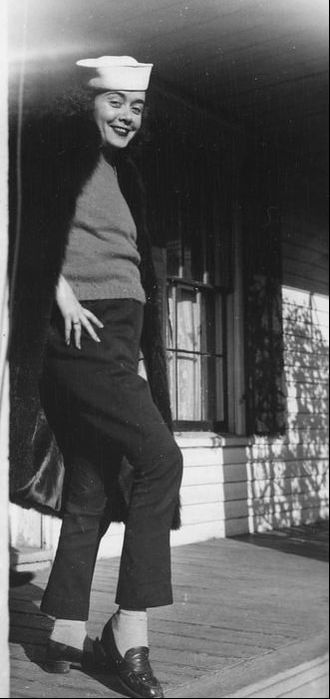

Now I wish I had not found this one. In the final week of an unsettling year, a young soldier – an immigrant, yes – risked his life once, twice, three times, four times, to save people in a horrendous fire in the Bronx. And then he went back a fifth time and did not survive. A week before, I had filed my final post of the year -- a reminder (to myself) to light a candle rather than curse the darkness. (Whole lot of cursing going on.) Emmanuel Mensah from Ghana personified the selflessness we all like to think we could demonstrate, if we had to….if it presented itself…. I came up with other examples, people I actually know. My friend Mendel of Jerusalem is a rabbi and family therapist (and writer, and runner, and Mets fan from Queens) who volunteers as a counselor with EMT units. We met for lunch on Long Island during his home visit. He told me that while trained medics deal with the physical part of a crisis, Mendel finds anybody who needs support. He never knows what language or accent he will hear when he takes somebody’s hand. They could be Jewish or Muslim or Christian. He does not care. He ministers. He lights the candle. Then I thought about my wife’s uncle Harold from Maine. He recently turned 95 and can no longer have home-made fish chowder and pie waiting for us when we drive up U.S. 1. Harold says he would like to be “with family” – aging, scattered -- but his “family” is right there in Bath, where he has lived most of his life. There is Ace, a surrogate son who returns regularly from the Southwest, and Cookie, a surrogate daughter who drives up from southern New England; they have skillfully handled the complicated details of a loved one who lives a very long time. There is Eric, whose family has been intertwined with Harold and his late wife Barbara. There is Martha, who drives Harold to the doctor even as she works full-time. There is Ann, the friend and nurse who has given diligent counsel. There is Germane and her daughter Diane, and Rich and Suzanne, and Bill, an in-law, and Kristi, retired Army colonel and nurse, who watched over Harold in a lovely retirement complex, as long as it was feasible. We have witnessed the best example of a classic American town, actually bustling with work (building warships on the Kennebec River, which Harold dredged in 1941) and the good will of people who know who they are, where they are from. But let’s double back to Emmanuel Mensah, from Ghana. The Times says he joined the Army National Guard and recently passed basic training. He planned to go on active duty, but before he did, there was a fire in the building. At the end of a dark year, I visualized Emmanuel Mensah’s military training – the preparation to protect people, to back up your buddies, to serve. In the months to come, I count on that developed impulse to follow rules. I suspect Emmanuel Mensah’s fine instincts as a human being, from his homeland of Ghana, were encouraged by the American military: when bad stuff is happening, go toward it. Emmanuel Mensah, an immigrant, saved lives in his final minutes on this earth. In the new year, his example shines.  Harold Grundy has visited 66 countries and 49 states. He likes to tell people about the construction he supervised in top-security places like Greenland and northern Maine and Guantanamo Bay. He also ducked bullets and bombs in Europe and Asia while delivering goods during World War Two. Whenever he and Barbara came home to Bath, Maine, they updated the pins on the map – which became the summary of his grand life, soon to reach 95 years. Barbara has been gone for a few years, and recently Harold – my wife’s uncle – began to need more care. He was in the right place – a cottage on the grounds of The Plant Home, alongside the Kennebec River, a 100-year-old retirement home, beautiful and comfortable, idealistically designated for people from the region. Harold held on by himself as long as he could, but when he began to need more care he was moved to the main house. The staff was fussing over him – everybody fusses over him – but he was feeling the huge change, even with a private room overlooking the river he dredged in 1940. How to deal with the tremendous sense of upheaval in his life? Harold is surrounded by good friends from Bath, a real town with thriving shipbuilding and generations of people with long memories and loyalties. Ace, his faithful surrogate son, has been visiting from Arizona. Cookie, a loving surrogate daughter and friend of Barbara’s, has been driving up from Connecticut. Ann, a retired nurse, has been volunteering her expertise. And Martha has been offering rides to doctors. Eric takes him out for breakfast. Dr. Paul, a nephew, has popped in, from his peripatetic life. This is the essence of community. We should all be so lucky. Still, understandably, Harold was having trouble adjusting. Ace and Cookie agreed that he needed more personal touches in his new room, but he was divesting traces of his life, including the map, with all the blue and green and red thumb tacks. The other day, my wife and I dropped in to meet the director of the Plant Home -- Kristi Hyde, a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, who served several active nursing tours overseas. This was our first meeting. Ms. Hyde invited us to sit at her desk. She sat squarely and leaned forward and looked my wife in the eye and asked how she could help. I had a flashback to three years in ROTC in college, when we were taught the fundamentals of leadership. (The military knows how to teach responsibility – thank goodness, I say.) Marianne said: “Harold has this map in the cottage…” Ms. Hyde smiled and said (as I recall), “We need to get that over here.” Twenty-four hours later, that large map (with the wooden frame that Harold, a master carpenter, had built) was placed on a wall outside the home’s activities room, where people pass all day. We took him downstairs to show him, and told him Ace and Cookie and Kristi Hyde had wanted that map to be with him. Harold smiled – and pointed – and began telling us stories about a few of his postings – Jamaica, Nigeria, Three Mile Island, and the perilous missions during World War Two. We stayed 15 minutes. There are always new stories. We’re back home now, and Harold is reportedly adjusting to his room squarely facing the river he helped dredge in 1940. He often tells how he ferried explosives into the middle of the river to help the blasters. His life keeps rolling, alongside the Kennebec.  Lulu has worn a lot of uniforms in her young life – from elite soccer teams in Pennsylvania. In a year she will be wearing a college jersey. Now she has a new uniform from another team, the Wegmans grocery chain, an institution in that part of the world. They screen and train their personnel well. Lulu’s brother George has been working there a few years, to help pay for college. Lulu can start saving from her part-time cashier’s job. An A student, she wants to be a dermatologist. In the fall, she will make early-morning rounds with personnel from a local hospital, in a program for select pre-med hopefuls. Soccer jerseys. Wegman’s uniform. Medical robes. Goal!!! * * * This just in on the family front: Another grand-daughter, Anjali, and family have driven from Sevilla to the Algarve, currently ensconced in a town named Lagos (Lar-gush). Anjali is not sending photos these days but we are getting the feel of the region.  May Spencer, College of New Rochelle, 1933 May Spencer, College of New Rochelle, 1933 A lovely article by Edan Lepucki in the Times this week had women considering photos of their mothers’ vibrant youth. Can a son do the same? I would think so. I went scurrying to the digital files I am assembling of our diverse family. My siblings and others have contributed photos they squirreled away in boxes or scrapbooks. May Spencer Vecsey passed late in 2002, at nearly 92. It is bittersweet to look back at the serious young woman in the old black-and-whites – the student with so much promise, the daughter permanently mourning a beloved father who died in her early teens. She does not strut her stuff for the camera. There is precious little smiling, even when her father was moving the family from Southampton, England, to Coxsackie, New York, with enough money saved for a large house in town and a farm just outside. The father is English (via Australia) and the mother is Irish and they are now upstate bourgeoisie, until her father hits a tree protruding onto an old country road now used for automobiles. This is the great tragedy of her life. (I saw her sob when Franklin Delano Roosevelt died in 1945; he was her surrogate father.) She apparently was always serious – a top student at Jamaica High School after her mother moved to Queens. A good friend of mine from high school says her mom used to talk with respect about May Spencer, writer and scholar. The college photos are the same: the photo with the hat depicts a sober young lady at the College of New Rochelle, a star in academics, yearbook, essays. Her classmates and the nuns said she would go far, even in the growing Depression. As Edan Lepucki notes in her sweet article in the Times, these young women in the photos cannot imagine what lies ahead. My mom would become a social worker, then a reporter for the Long Island Press, then society editor, where she would meet my father. (“They met at the water cooler,” my brother Pete has said. “Pop was buying.”) They would share a belief, a passion, if you will, for The Left; they were management but they would go on strike with the workers, facing the Cossacks on 168th St., and would never get back in that building again. Could she envision hard times during the War, my father fearing a blacklist but always having work in the newspaper business? Could she see herself learning to cook, clean, wash and iron, to care for five children within 10 years, to care for her dying mother, to go through hard times in the family and then get whacked by multiple sclerosis – and fight it off with long daily walks up to Cunningham Park with her loyal dog Taffy? She was strong. I find no evidence of her mugging for the camera, no frivolous outfits. But I remember once, in a casual aside, my father compared her to a movie actress. Pop knew movies as well as he knew his Brooklyn Dodgers and politics and books, but I cannot remember which actress it was. His attraction was real. That’s all I know. She put her seriousness and her morality and her intelligence into her family. All five of us are doing well. That studious young woman in the hat made sure we did. “It is better to light a single candle than to curse the darkness.” -- Attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt. Hindus celebrate Diwali at different times of the year. We once saw uniformed bobbies dancing with celebrants in Trafalgar Square, London. Very sweet. This October, 35,000 people celebrated in Leicestershire, England, my mother's ancestral roots. This year Hanukkah begins the same evening my family celebrates Christmas Eve. We have had a menorah in our home for years. In the next few days we will go for a good meal at a modest Halal restaurant near us – and celebrate the diversity of this blessed country.  This came over the electronic transom, a mass posting by Bishop Sally Dyck of the United Methodist Church, about the symbolism of an inverted tree, in a store near her: “Jesus’ birth over 2000 years ago was in the midst of unrest, oppression and violence as the people of Israel labored under the Roman Empire. He brought a message of hope, peace and justice in the midst of a time and place where there was no hope, no peace and no justice. Jesus came to turn the values of the Empire upside down!” Here’s a Santa’s workshop for you – the local bicycle shop, packed with gleaming machines with that nice-new smell.

But here’s the problem: I dropped into Port Washington Bicycles at 18 Haven Ave. in Port Washington, L.I., the other day, to say hello to the staff that keeps me rolling all year long. Things were way too quiet for December. People are not making a big rush on bicycles for holiday presents for children, the staff told me. Apparently, kids hunker in their homes, flicking their smartphones, playing games and gaping at who-knows-what. They are using their thumbs when they should be using their knees. “It used to be that when kids were punished, they were made to stay indoors,” said John Pappas, one of the bosses. “Now if they are being punished, they are sent outside.” It is a true social phenomenon. As American children grow heavier, they do less. Helicopter parents drive them to play dates. In our neighborhood park, we have modern play equipment with all the apparatus clustered, so parents can hover, holding cellphones and Starbucks cups. Gone are the days when kids could swing or climb in a corner of the park, daydreaming, or take a walk or ride a bike, looking for their friends in the neighborhood. At least, that is how it looks to me, as well as Ralph Intintoli, the owner of Port Bicycles, and his two colleagues, Pappas and Mike Black. Over the years they have sold me a Schwinn and more recently a Trek Hybrid, as well as a treadmill and an exercise bike. They also sell car racks and are terrific at service. Pappas also gives paid lessons when it’s time for children to stop using training wheels and take off on a two-wheeler. However, at holiday time, when the newest electronic gadget is the present kids absolutely must have, parents don’t buy the traditional new bike to put under the tree. Actually, grandparents buy bicycles for kids more than parents do, Intintoli said. When I was there, a guy my age was buying a beautiful Trek to bring to a grand-daughter on a Christmas visit. I hope the girl appreciates the gift, and takes off down the block to play with a friend. When Harold Grundy helped dredge the Kennebec River in 1941, he knew how deep the channel was, and where it ran.

Harold Grundy – my wife’s uncle – still lives alongside the Kennebec in Bath, Maine. Just a mile up river, the Bath Iron Works has just finished the newest and biggest American destroyer, the $4.4-billion U.S.S. Zumwalt. From the back window of his cottage, Uncle Harold has watched the behemoth on test runs. Recently, he read in the paper that the skipper of the Zumwalt, the marvelously named Captain James A. Kirk, was curious about the history of the dredging of the river. At 94, Harold remembers it all – how the workmen lived in modest cottages near the river, how he carried dynamite in a primitive pickup truck along a bumpy dirt road, lifting 100-pound packs onto a modest skiff and ferrying it out to ships, whose drill shafts went 90 feet deep, loosening thick slabs of rock. They went out in almost all weather, sometimes sleeping on board, helping dump the excess rock far out at sea. After the river was dredged, Harold worked for the Merchant Marines, ferrying ammunition, serving in murderous combat in the South Pacific as the ship’s carpenter, ubiquitously called “Chips” by the sailors for the sawdust and slivers produced by their labors. He saw ships blown to bits all around him, saw sailors on stricken ships waving a solemn goodbye as they went down. When the war was over, the Merchant Marine gave him a handshake but because he was technically a civilian he receives no military pension. Oh, well. He worked for the military for many decades, helping build high-security structures all over the world. Last year, nearby Bowdoin College honored him with a show of the photos he took in Greenland and other sensitive places. I wrote about it: http://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-heir-of-quakers-who-kept-his-country-safe Living alone since the death of his beloved wife Barbara, Uncle Harold read about Captain Kirk’s admirable curiosity and wrote him a letter, sharing the copious details in his memory. A few days later, Captain Kirk paid a visit to Harold's house, a mile from the Bath Iron Works, but Harold was out running errands. The captain left a unique gift -- a handsome peaked cap, dark blue with gold braid, and the name of the U.S.S. Zumwalt printed across the front. On the back was the name: Hal Grundy. Uncle Harold keeps it inside, in a large clear baggie. It’s not for all weather. The Zumwalt left Bath on Sept. 7, heading toward San Diego and points beyond. Uncle Harold will follow her progress, knowing that he helped get her from the Bath Iron Works out to sea. Well done. |

Categories

All

|