|

Harold Grundy moved around a lot. Building things.

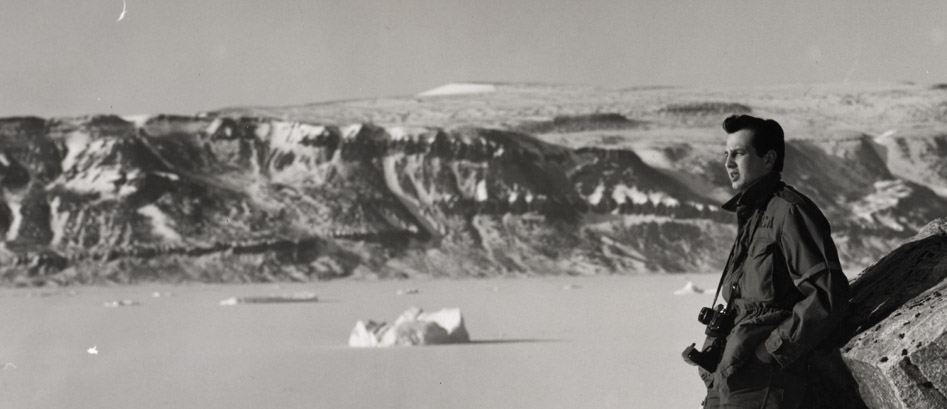

His family knew he went to Greenland and Africa and Guantanamo Bay and other places around the world. Now 93, Harold Grundy -- my wife’s uncle – is being honored with an exhibition of 193 of his photos, “Cold War in a Cold Climate,” at Bowdoin College. Raised in the tradition of the Rogerene Quakers of Eastern Connecticut, the eight Grundy siblings did not smoke or drink and ate mostly farm food; five are still alive, 89 to 96.\ During World War Two, Harold joined the merchant marines, loading ammunition during four Pacific invasions and three typhoons with 90-foot waves. His sector of the convoy was called Coffin Corner. When he came home to Maine, Harold supervised construction and maintenance in some of the hot spots in the world. He spent several years at the base at Greenland where radar was pointed directly at the Soviet Union. There was a 1,000-foot tower he had to climb periodically to make sure it was safe. Later he spent time at Guantanamo Bay, supervising a desalinization plant for the American enclave, and lived in Pennsylvania, supervising the shield for the nuclear plant at Three Mile Island. We have family near there; don’t worry, he said; he made sure the concrete exceeded standards. * * * My wife and I recently drove up to Bath, Maine, where Uncle Harold is mourning his lovely wife Barbara, his companion for seven decades, who passed last Dec. 14. Barbara lived much of her life on the same street where she was born, within view of the Kennebec River. Harold came to Bath for a construction job in 1941, dredging a 50-foot channel so new destroyers could glide down to the ocean. Barbara suffered from childhood diabetes and degenerative arthritis but she always worked, and sometimes traveled with Harold to exotic places. She had every joint replaced in time, but they would take off on a two-month drive to the west coast and back – half gypsies, half homebodies. Their only child, Roger, was shot up flying a helicopter in Vietnam, came home and died in a car wreck a few months later. Several of Roger’s friends act as surrogate sons. One of the friends is Eric Johnson, whose father, Sam Johnson, ran the Chicago Bridge and Iron company, dispatching Harold around the globe to solve construction emergencies. Sam Johnson paid for Barbara’s operations over the years. In their retirement, Harold and Barbara started a woodworking shop, just for fun. Later they turned the business over to Eric, who produces thousands of wooden items. (Anybody with a work bench will have trouble resisting the on-line catalogue.) In her final years, Barbara helped Harold put together a booklet of his career and their travels.. After she passed, he asked Bowdoin in nearby Brunswick if it was interested in the Greenland photos; the curators at the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum eagerly accepted, putting them on display in Hubbard Hall on the beautiful campus. Much of the family attended a reception on Sept. 19. Among those attending was Harold’s very accomplished nephew Paul Grundy, M.D., another world traveler who is IBM's Global Director of Healthcare Transformation. Paul said his dad, Elwin, registered as a conscientious objector early in the war and was used in a starvation project that caused many of his teeth to fall out. We got to Maine in October and Harold gave us a tour of the exhibit -- stories about the Eskimos who had rights to visit the base, how the Americans, who lived six to a hut, arranged hoods around their heads so they would not freeze outdoors. He remembered the perils of landing near an Arctic mountain; the rare home leaves. Once the radar went down for a few weeks but two other posts readjusted their signals to keep track of the Soviets. We drove up the coast to visit Aunt Peggy Sukeforth (an in-law of the great Clyde Sukeforth) ; saw the sign Morris Povich (yes, that Povich family) on a clothing store in downtown Bath; saw the three shifts at the Bath Iron Works, still pointing ships toward the sea. Harold told us stories about the four Pacific Landings, how a buddy sneaked him on a reconnaissance flight at Iwo Jima. Once he delivered a car to General MacArthur, who shook his hand. Once in London he and a pal went sight-seeing at 10 Downing Street; Winston Churchill happened to arrive, waving the V-for-victory sign and shaking the hands of the two Yanks. Omce a young senator from Massachusetts sat next to Harold in a Boston train station; John F. Kennedy confided he was planning to run for President. Harold has been interviewed for several documentaries, including one by Ken Burns. On our last evening in Bath, Uncle Harold served us lobster chowder he had made, making sure I had doubles, with crackers. The chowder was wonderful, almost as wonderful as the modest stories of his glorious American life.

Brian Savin

10/14/2015 07:46:58 pm

Every well-lived life is sacred. Your Uncle clearly defines "well-lived." But I'm mostly envious of the chowder. Get his recipe.

Angela Hayward

6/1/2016 10:15:00 am

As a great-niece to Uncle Harold, I can attest to the lobstah chowdah (how us Mainah's say it) being out of this world delicious. He is a very humble man, but he is one of my heroes. No greater love than between he and Aunt Barb. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|