|

"There are 9,388 graves in the cemetery, most of them in the form of white Latin crosses, a handful of them Stars of David commemorating Jewish American service members. As antisemitism rises again in Europe, they seem somehow more conspicuous." ---Roger Cohen, The New York Times. "D-Day at 80" -- June 6, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/06/world/europe/dday-80th-anniversary-veterans-remember.html Marianne Vecsey noticed the same thing, back in the mid-70s, when we drove with our young children to Normandy, in the sweet damp spring. Part of Marianne's ancestry goes back a thousand years to Normandy, but this was not about us. This was about the Allies who died during the invasion, now 80 years ago. We live in New York; we tend to notice stars amidst the crosses. "You hear the number, but when you stand there, and see the graves with crosses and stars, it sinks in. It's stunning, actually," Marianne said on D-Day 2024. Roger Cohen had the same reaction. Of course he did. Roger is one of the greatest Times writers of any generation -- fearless, perceptive, the voice of the underdog, the champion of the fallen. I've spent great times with Roger running around Germany during the 2006 World Cup or watching him suffer for his Chelsea F.C., in some New York pub. I've read his poignant tribute to his mother, to all who suffer, in his 2015 book, "The Girl From Human Street." https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/22/the-girl-from-human-street-review-roger-cohen-memoir-motherodyssey-of-loss I miss him in New York -- Brooklyn, to be specific, but now he is right where he should be, in the middle of it, as Paris Bureau Chief, preparing his masterful text for the 80th "anniversary." Marianne and I and "the kids" made the same pilgrimmage north from Paris, borrowing a friend's chugging sedan, heading toward the tangy air of salt water, toward Mt. St. Michel. (I had learned to love Mt. St. Michel, reading Richard Halliburton in grade school.) Now we were there, in a scruffy little gite near the beaches, in a spring so damp that sheets did not dry on the line. We saw the Bayeux Tapestry, of course we did, and then we headed to the beach. Funny, as we sat atop one of the sandy cliffs, we heard distinct German voices behind us -- three cars, three sporty couples, no longer the enemy, just modern Europeans on spring holiday, to see the Normandy beaches, the landing now three decades in the past. We took in the logistics of that landing, what it was like to be in those landing craft. The only person I knew who had been in one of those boats was Lawrence Peter Berra of St. Louis; but Yogi never talked about it, just as his teammate Ralph Houk barely alluded to his battlefield commission at the Battle of the Bulge. Veterans don't talk much. Marianne learned that when she was a lifeguard at a village pool on Long Island. Some of the older town workers had been in the war, but never shared details. Now it is 80 years, and centenarians will talk, particularly if a master journalist like Roger Cohen asks the right questions, the right way. People talk to Roger. Read his words; look at the photos. Marianne stored the visual memories, the visceral impact, of the Stars and the Crosses. She's an artist -- has a lifetime of paintings out there.

We loved our April in Paris, staying in a sous-sol in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The Metro. The Louvre. The Bois. Then we came home and resumed normal lives, and one night Marianne waited for the family to go to sleep, and she painted her geometric tribute. This month Roger Cohen has been, as always, in the right place, recalling the Canadians, the Europeans, the Americans, who stayed behind, in Normandy. (This is one of those pieces I hate to write, but am compelled to do.) It was March in 1953 and I bumped into John Vinocur in the GG subway, the local that ran underneath Queens Blvd. John was a year behind me in Junior High 157 but we had gotten to know each other on the daily ride to Rego Park. The headlines in the papers – everybody read a paper in those days – The Daily News! The Times! The Trib! The Mirror! – and these were just the AM papers -- were about the death of Joseph Stalin on March 5. The question was, would the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S. be lessened or heightened by whoever came next, a fun discussion in any decade. John was a news junkie and so was I and we chatted animatedly, and no doubt loudly and ostentatiously, until the GG local had arrived at our stop. I thought of that subway ride when I read that John passed Sunday in Amsterdam, yet another great city he knew from his time as reporter and editor at the Associated Press, International Herald Tribune, New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He lived the dream that was perhaps in our brash Queens minds on that March morning of 1953. The obituaries tell of his accomplishments and hint at his bluster. I know somebody who worked in the Paris office of the IHT for a year in the early 80s – “dashing and vibrant” were the words she used. That was when the IHT was an eccentric wing of the Times, its office never far from the Champs Elysées, its product a must-read for ex-pat or vacationing Americans, long before the Internet. News from home! Sports scores! It was the offshoot of the paper being hawked by Jean Seberg – “New York Herald Tribune!" – in Paris, as Jean-Paul Belmondo sharks her, in the 1960 movie “Breathless.” That was the same world sought out by John Vinocur, who had played a little basketball at Forest Hills High, went to Oberlin, and then off to France, where he played semi-pro basketball. The hoops were part of his rep, and he often mentioned it to me, knowing I would be properly impressed. At some point, John went to work for the Associated Press in Paris, earning good assignments like the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Here is eager young John Vinocur, covering the massacre of Israeli athletes, described by another deceased pal of mine, Hubert Mizell, late of the St. Petersburg Times. "A native New Yorker, he… matriculated to backwater France, learning the language from natives and picking up money playing semi-pro hoops.” Hubert then describes how John “ignored police warnings and scaled a fence to get close to Building 31.” That would be John from Queens, scaling a fence. I can find no reference in his obit to how John got his job at the Times, but as I recall it, John was working for the AP in Paris when the movie “Last Tango in Paris” came out, portraying the club world of Paris in all its seediness, and John went to one of the raunchier clubs and wrote about it, and somebody at the NYT noticed. That’s how it worked: somebody likes your clips. John worked in the home office of the NYT for a while but my guess is he was used to being The American in Paris, so he went back. We ran into each other over the years, and would share opinions of New York sports, our Queens voices the loudest in any brasserie or café, still bonded from the GG local subway. *** If you can leap the paywall, you can find Sam Roberts’ obituary of John Vinocur here: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/06/obituaries/john-vinocur-dead.html *** And just to get a feel of the dream, Paris in the 60s, here is the clip from “Breathless:” While Notre Dame was burning on Monday, several American commentators referred to the book, and subsequent movie, “Is Paris Burning?” – about the German general who allegedly disobeyed Hitler’s orders to level the city during the retreat of 1944. The cathedral is a geographical center for France, and the beating heart of Paris to all of us who visit and love it -- or even have the privilege of living there for a month here and there. We took our three children to Paris in April of 1975, almost immediately visiting Notre Dame, where our youngest fell in love with the gargoyles who still broodingly guarded over the city, even as flames raged on Monday. On that family trip, three decades after the War, we talked about World War Two, grateful that this beautiful city, this beautiful cathedral, had survived. On Monday, les pompiers, the firefighters, controlled the blaze. Paris was burning. Of course, people thought about the book and the movie. However, when I went to the Web, I realized there is considerable historical debate about whether General Dietrich von Choltitz overtly acted to save Paris or merely dragged his feet, while saving his own life and shoring up one tattered corner of his reputation. Did the general really say no? "If he saved only Notre Dame, that would be enough reason for the French to be grateful," the general's son, Timo, told a British newspaper in 2004. "But he could have done a lot more.” The general’s alleged act of refusal and respect for a glorious city – perhaps self-aggrandizement -- comes up sometimes when conscience is the subject. From my American perspective, I immediately linked the survival of Paris, the endurance of the cathedral on the Île de la Cité, with overt acts of terror and torture perpetrated by Donald Trump on the border with Mexico. Who says no? Who follows the law? Who cares for fellow humans? The legend of a general who participated in the Holocaust, is back in the ozone, revived by the horrible fire. We want to be grateful to a German general who may have said “No,” but there are so many questions. He said he acted out of military prudence, as a trained general, who surely considered himself above the unskilled, ignorant, raving “leader.” Germany of the ‘30s never had enough leaders who could say “no.” Does any nation have enough people in positions of power, responsibility, who can muster the inner strength to say no? This is a very current debate for those Americans who now consider the military – the tradition of service, adherence to law – as one of the last strengths of the nation. Who will say no? I am reminded of this every time I see videos of one of Trump’s people, Kirstjen Nielsen, sighing patronizingly when questioned by (Democratic) representatives about putting children in cages. Soon afterward she was pushed out by Trump for not doing enough to separate and harm (torture, if you will) les misérables on our borders. The urge to survive, by Gen. von Choltitz might have helped save Paris in 1944. Is inaction enough when evil orders are given? Who will say no? * * * https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dietrich_von_Choltitz https://www.thelocal.fr/20140825/nazi-general-didnt-save-paris-expert https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1966/11/06/83551081.pdf Awaiting kickoff, I thought about our first trip to Europe in 1966. My wife and I started in Brussels, picked up our car, drove south and west.

At lunch time, we stopped in to a country restaurant. The squawking we heard in the courtyard soon turned into poulet à la cannelle – chicken with cinnamon. My wife thinks it was in France. I think it was Belgium. We giggled to ourselves because we were in Europe; in a way we had come home. As the teams entered the field, I began thinking in duplicates. Georges Simenon from Liege wrote endlessly about a police inspector -- in Paris, where he lived for many years. Jacques Brel from Brussels wrote songs from his Flemish background ("Les Flamandes," "Marieke") -- but when his songs were adapted into the immortal English cabaret version, the title was, mais oui, "Jacques Brel Is Alive and Living in Paris." https://masterworksbroadway.com/music/jacques-brel-is-alive-and-well-and-living-in-paris-original-off-broadway-cast-recording-1968/ France had been to two finals, splitting them. Belgium had never been to a final. Before the match, an embrace between Didier Deschamps, French coach, and Thierry Henry, Belgium assistant, comrades from 1998. They’ll always have Stade de France. So much talent on the field -- a vast markup from the quarterfinals. Each team fielded a giant engine, worthy of the train line, the TGV -- Très Grand Vitesse, very high speed: Kylian Mbappé from the Paris suburbs, father from Cameroon, mother from Algeria; Romelu Lugaku from Antwerp, of Congolese ancestry. In the first half, I saw two familiar Premiership foes grappling: Paul Pogba of France and Manchester United; Vincent Kompany (with his Master’s in Business Administration) from Manchester City. The battle of Lancashire, alongside the Neva. Early in the second half, time froze. Samuel Umtiti of France, a defender, moved forward on a corner kick and got inside Marouane Fellaini, the tallest man on the field, for a header into the corner of the goal. They played out the match, ancient neighbors, joined at the hip. At one point I saw alert, versatile Antoine Greizmann of France battling for the ball against alert, versatile Eden Hazard of Belgium. I retrieved a memory of visiting my relatives, Jen and Sam, in southwest France, where they have a home alongside a working farm. (The cows walk outside the windows on their morning forage.) Sam and Jen introduced me to the farmer, who discussed the rules and inequities of the European Union. I heard the farmer say “Bruck-cells!” like a man spitting on the ground. The match ended with a 1-0 victory for France. Deschamps and Henry found each other and embraced again. One Belgian player pumped his arm and shouted “On y va!” to the fans. Let’s go. I hope country restaurants still serve poulet à la cannelle on the border between the two nations. George Butterworth did not see himself as a composer. Rather, he was a well-rounded musician, who, like so many other privileged English men, enlisted in the military early in what they called The Great War.

(I wrote the first draft of this a week before the Donald Trump Heel Spur controversy; of course, I did not serve in the military, either, having had two children young. George Butterworth did volunteer for the Great War, at the age of 29.) I never knew much about George Butterworth except as the first of three composers on a lovely Nimbus CD, “Butterworth, Parry & Bridge” -- three British composers, brought together in a 1986 recording by William Boughton and the English Symphony Orchestra. In my iPod, that arrangement blends into one long summer afternoon in the British countryside, idyllic, gentle, peaceful. It takes me back to afternoons when we used to visit a friend in mid-Wales. I paid more attention to the name Butterworth when it popped up in my wife’s ongoing genealogy study. One of her ancestors married a man named Butterworth in the 19th Century somewhere in Lancashire. It does not appear to be the same family, inasmuch as George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was born in London. His father was an executive on a railroad, who sent his son to the best schools—Eton and Trinity College, Oxford. After university, Butterworth traveled around England, sometimes as a professional morris dancer (there was such a thing in those days) and collector of folk songs. Sometimes he went around with Ralph Vaughn Williams, whom he prodded to expand a short piece into what would become his “London Symphony.” Butterworth expanded on the folk song, “The Banks of Green Willow,” and wrote music to accompany the poems of A.E. Housman in “A Shropshire Lad.” But "composer" was a label he resisted. In August of 1914, Butterworth joined up and was sent to the front, where armies were hunkering down in the fields of Belgium and France. He was made a lieutenant, put in charge of coal miners from Durham, with whom he had great rapport. He was shot once in the Battle of the Somme but recovered and went back to the trenches. On Aug. 5, 1916, George Butterworth was shot by a sniper. His body was not recovered but friends back home made sure his music was written down and survived the war. Ursula Vaughn Williams, the widow of the composer, kept Butterworth’s music in circulation. (I wish I had known that while watching that force of nature, Frances de la Tour, portray her in the recent movie, “The Lady in the Van.” ) “The Banks of Green Willow” has come to represent the people who died in the Great War. There is a Butterworth B&B in the French countryside, not far from where George Butterworth fell, a century ago, Aug. 5, 1916. Our journalist/scholar family friend in Istanbul writes about the upheaval in her country. Please see:

www.phillymag.com/news/2016/07/19/turkish-coup-philadelphia/ * * * We know Nice. My wife was recalling how she and our daughter Corinna walked that promenade years ago. We always talk with awe about France. Our friend Sam who lives in the Alps says the nihilists hate it because it is beautiful. We also know Istanbul. We went there in the lush fall of 2012. There were rumblings, omens, but also waves of beauty and history and comfort. We walked the hills, took trolleys along the Bosporus, visited mosques, drank coffee. One day we took a ferry to the Princes islands, a leisurely hour north of the city. The main island, Büyükada, was like one of those vanishing bucolic American islands. We bought baked potatoes for takeaway and strolled the streets. On the ride back we passed Yassiada, a smaller, more rugged island. “That’s where they kept political prisoners,” a chatty man told us. We looked it up. A former prime minister, Adnan Menderes, was held on Yassiada before being executed at a more distant island on Sept. 17, 1961. That is apparently the most recent political execution, as Turkey sought its place, straddling Europe and Asia. We visited Asia – Uskadar, with markets and cafes and an admirable book store. We consider Turkey one of the best vacations we have ever taken -- the farms and villas and rolling countryside near Izmir and Ephesus. The other night we watched glimpses of the troubles -- bridges and hills and buildings that looked familiar, but this was no travelogue, not with crowds in the streets, soldiers in the streets, rumors and bullets flying. Will there be new executions in the wake of the attempted coup? Could we once again take that modern T1 tram line from Kabataş to Bağcılar, gliding through neighborhoods, chatting as we did with a nice Jordanian couple? More important, for the people who live there, can that great city endure, with one foot in each world? We sit home and grieve for the great places. Generally, I ascribe to the Dumpster Theory of Life. When we pass, our kids will toss all that stuff into a gigantic bin. But just as a gesture to downsizing, we were making pretensions of cleaning out the attic – something, anything.

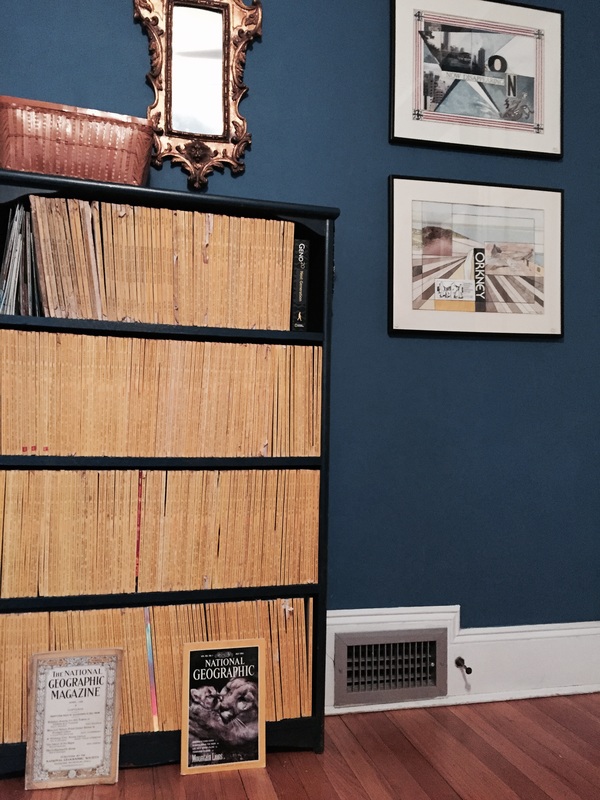

How about those National Geographics? They’ve been up in the attic for five years, maybe 10. The Web says nobody wants Geographics, not for money, not for free. Try an old-age home, the Comments say. Wait, this is an old-age home, technically. I went to the attic and put them in doubled-up shopping bags, flecking off the dust and grit. A few on the top were damp from a long-patched drip near the chimney. Ninety-nine per cent were in fine shape. I could hear the voices of the writers and the editors and, yes, the subjects – the Uighurs of China, the Zulus of Africa, the clog-dancers of Appalachia, the explorers of outer space: “Look at us. We were important then. We are important now. Get us out of the attic, to somebody who appreciates us." I lugged the magazines, 20 or so to a bag, down to the second floor. (The movable wooden stairway with its sturdy steel housing is itself a relic, from the great builder, Walter Uhl, in the mid-30’s, when homes were made to last.) I began my exploration of ancient history, chronologically: A few dozen older issues we had collected from a library sale on the North Fork of Long Island.

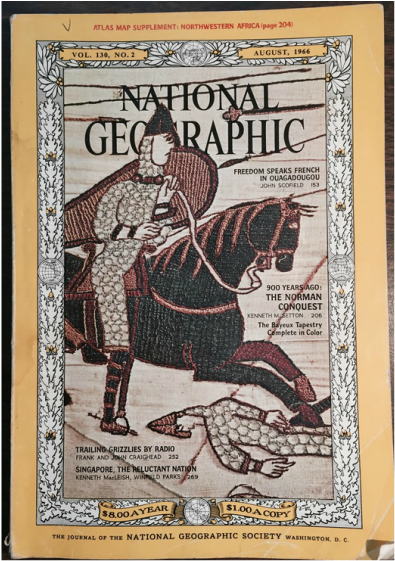

By 1963, we were subscribing, leaving the Geographics around, to make our children, present and future, curious about the world out there. In August 1966, shortly after my wife and I made our first Europe on $5 a Day trip to Europe, there arrived an issue with “900 Years Ago: The Norman Conquest. The Bayeux Tapestry, Complete in Color.” We saved it, of course, and in April of 1975 we took all three children to France for a month, riding the Métro and glorying in the baguettes (trés crustillant) and driving out to Normandy in a wheezing old Citroen a friend had lent me. The August, 1966, Geographic came with us and we consulted the 46 pages that explained every figure of the Bayeux Tapestry as we walked alongside it. Now the same edition of the Geographic was in my hand, bringing back memories. We could not part with these heirlooms. I painted a cabinet dark blue and soon filled it with Geographics -- May 1928 in the upper left corner, all the way to 1992, lower right. Then we put the last 15 years in a hall shelf. (We cut the subscription when our grandchildren began thumbing through smartphones instead of pages.) The National Geographic endures, bless its earnest heart. Our “collection” – approximately 600 editions – is home. I am poking through the Bayeux Tapestry, thinking of Galette Bretonne and the coast at Omaha Beach. The Dumpster can wait. It took a week

before I could even link the horror in Paris with my little site. Then, in my head, I formulated a tribute to Paris, But it turned out, I had written it, last January. http://www.georgevecsey.com/home/nous-sommes-tous-francais I cannot write another one about the deep shuddering joy of being in the City of Light On a Friday evening. One ex-pat friend, Living in La France Profonde, wrote me, “No one does life better than the French.” That’s why they are targets, he added. Another friend is flying over, next week. “It'll be my little contribution to saying %$&# you to the murderers who tried to take the city away from those of us who cherish it and what it represents.” I won't write about the narrow streets Or the aroma of coq au vin in the mist. Better I write about the French people Who spoke to us in English after 9/11 and made room for us on the Metro. Now I watch survivors like the beautiful couple on Anderson Cooper, the woman's face haunted the young man (a model, I looked it up), volunteering sympathy for Syrian migrants, who have their own misery. Another man lost his lovely wife In the music club and wrote a tribute to her, And promised to live without hatred. Is it possible? What a strange sport, cycling.

More than any sport, it contains multiple stories and multiple champions, wheel to wheel on narrow mountain roads. The Tour ended Sunday where it always ends, in Paris, with the Eiffel Tower in the background. When the survivors struggled up the Alpe d’Huez on Saturday, either Phil Liggett or Paul Sherwen, both English, noted on NBCSN that from the peak of that mountaintop the riders could see the Eiffel Tower. Whichever one it was, he was being poetic, but what a symbol for this singular event. I remember the penultimate race in 2004, a time trial out east in Besancon, that made Lance Armstrong champion for the sixth straight year. As soon as work was done, I jumped into the car with James Startt and Sam Abt, two Americans in Paris. James started his engine and gunned onto the Autoroute. I close my eyes for a few minutes and woke up and saw a strange phenomenon looming out the back window. It was the Eiffel Tower, all lit up on a summer evening. James had found a time warp. We were in Paris. The same thing happened Sunday in rainy France, when the peloton skidded its way into Paris on the ritual final day. Every finisher was a champion of the human will. That’s why people stand in the rain or sun and cheer. Saturday’s true finish up the Alpe d’Huez had three champions, all properly celebrated by Liggett and Sherwen. . There was a Frenchman, Thibaud Pinot, barreling ahead on the final climb, to win the stage, a victory for the host country, living on the memory of past glories. (Like England in soccer.) Then there was a Colombian, Nairo Quintana, showing panache, the favored character trait of the Tour, by trying in vain to win the Tour with a blast up the Alpe. And there was the actual winner, Chris Froome of Great Britain, who gained from a great support system and his own dogged riding, to win another Tour. It is a strange sport. My friend Alan Rubin, soccer keeper and mentor, added a comment on this site recently, wishing he knew more about the sport. I always felt the same way -- and I was covering it, or at least writing columns, often about the apothecary wing of cycling. The best I could tell Alan is that the Tour is a mix of the Daytona 500, the New York Marathon, the roller derby, and the old single-wing formation in American football, when everybody pulled to lead the ball-carrier. My advice would be to read the collected works of Daniel Coyle, David Walsh, John Wilcockson, Juliet Macur, Sam Abt and James Startt. You’ve got almost 49 weeks. (Sam Toperoff lives in the Alps with his family. He played basketball at Hofstra and later taught there and has had an admirable career writing books and documentaries before retiring in France. The Tour de France has been in their region in recent days; I suggested he send his impressions.

(At first, Sam was going to write from the largest town, Gap, but then he wrote why that was not possible: (“Local shepherds will be staging a manifestation – protest -- because the government is protecting wolves, which they claim are attacking their flocks. Italy, just across the mountains, doesn't have a wolf problem because the shepherds sleep with their flocks; French shepherds do not. Still, the local shepherds plan to disrupt the Tour by loosing 3,000 sheep when the cyclists approach Gap. Seriously. I'm not making this up; this is France, and I love it.” (Instead, Sam waited until Thursday, and he wrote these words and his daughter Olivia took some photos.) By Sam Toperoff Good evening Mr. and Mrs. North America and all the ships at sea, let's go to press. (It's an opening that takes me back to my childhood and so does riding a bike around Laurelton, Queens, when I was about nine or ten.) I always thought bikes were for kids. Not in Europe they ain't! I've never been as taken with the Tour de France, the best bike-riding ever, since I watched the great Bernard Hinault bike past me to victory forty years ago on an uphill climb I could barely manage while walking. I had found myself in the French Alps par hazard and since there were no basketballs around and no one to hit fungoes to, I had to start biking. Frankly, it was the most demanding physical activity I'd ever engaged in. I biked these hills in summer until I was seventy. I actually put the bike away on my birthday after I came up two hairpin turns from a road below my house and barely made it. The other day, to win the 18th stage of this year's Tour, Romain Bardet went up scores of hairpins and scaled the Alps themselves during a 170-km. race while being chased by 170 other world class riders. These are remarkable athletes indeed because of the physical and mental demands they face daily over three-week period. All in all, the race is over 2,000 miles. Bardet is a young Frenchman, and a Frenchy winning even a stage has become a rarity these days; no one from Gaul has won the Tour since the above-mentioned Hinault, who did it thirty years ago! And so tonight, French television is nothing but Bardet, Bardet, Bardet. Of course, it's hard to watch the Tour without wondering how these men can do what they do, especially when it comes to their need to recover overnight after such enormous effort. Even though all of Lance Armstrong's victories have been vacated because of his now-admitted use of illegal stimulants, it is hard to watch such remarkable performances and not remain somewhat cynical. The Director of the Sky Team, for whom Christopher Froome rides, the Englishman Sir David Brailsford, is on television almost daily assuring viewers (his French is perfect) that his team is clean. "I don't blame people for being cynical," he said the other day, "but other than the unlimited testing of my team and giving the public my word, what can I do?" The shadow of Lance Armstrong still shades the Tour. I despise him for what he did. Worse, he put doubt in my appreciation of what I am witnessing; cynicism's worst effect is that it robs one of pleasure. And poor Chris Froome -- a truly great rider -- and young Romain Bardet -- and my particular favorite Alberto Contador -- they all become objects of suspicion. Nevertheless, I'll be in front of my set for tomorrow's stage.” Merci, Sam. It was my first day around the Tour de France, a rainy morning, July 14, 1982.

There was a time trial that holiday, around Valence d’Agen in the south, but it was too early to go out in the rain. I was with Roby Oubron, former cyclo-cross champion and then a mentor to Jonathan Boyer, the first American to ride in the Tour. Roby was a true son of France, a resister during the war who loved America. He met me for breakfast in the hotel and brought along a friend, but I did not catch his name. I tried to follow the shop talk in French, and they slowed it down enough for me to be included. We dawdled over breakfast, more than the basic croissant and café au lait. Then I asked the waiter for the check. “Ah, non!” Roby blurted. His friend, a polite older man in nondescript foul-weather gear, was also asking for the check, but I had gotten there first. Trying to overcome the language gap, Roby explained that his friend was wealthy, loved cycling, and always paid, always. I politely told the man that the New York Times would insist, journalistic ethics and all. The man seemed bemused by the concept of journalists grabbing the check, but he nodded his head gravely and thanked me. Later, in the car, racing around behind Boyer on the time trial, Roby explained to me, as best we could work out, that his friend was Guy Merlin, the founder and proprietor of Merlin leisure homes and camps all over France. Guy Merlin sponsored cycling teams, and his $20,000 condominium in the south of France was the largest prize for cyclists on that 1982 Tour, I found out later. We barreled around southwest France the next few days -- Rob Ingraham, Boyer’s agent, called Roby “Mario Andretti," for his heavy foot – and my short visit ended up in the Pyrenees, with the goats. Roby knew everybody. He would drive alongside Bernard Hinault on some narrow mountain pass and ask why he was making a breakaway. It was like sitting in a baseball dugout during a game with a wise elder like Ted Williams or Roy Campanella. I adopted Roby as my alternate father-figure and think of him every Quatorze. As long as Roby lived, he told the story of how I grabbed the check from Guy Merlin. * * * Bonus: a short video of Roby winning a cyclo-cross stage, July 12, 1945, apres la paix. http://boutique.ina.fr/video/AFE86003353/robert-oubron-remporte-le-cyclo-cross-delavigne.fr.html I was watching the Tour de France on Tuesday morning as it swept through the city of Charleroi, in Belgium.

My mind went back to a nasty morning in 2004, at a staging area in the very same Charleroi, when I had a taste of the grim war being fought by Lance Armstrong’s minions. Totally by coincidence, I am reading the new book about the battle of Waterloo, by Bernard Cornwell. Another conqueror also passed through Charleroi that fateful month of June, 1815. His name was Napoleon Bonaparte. So now they are fused in my mind, the man on horseback, the man on the bike. As the Tour began in 2004, a new book came out, “L.A. Confidentiel: Les Secrets de Lance Armstrong,” by David Walsh and Pierre Ballester, containing many accusations of doping by Armstrong and his team. The book was only in French. I bought a copy at the Brussels Airport and was reading it as the Tour began in Liege. One of the most convincing sections was about an Irish masseuse, Emma O’Reilly, who recalled how Armstrong had tested positive for steroids in 1999, only to have a doctor file a note saying Armstrong had been using a form of steroids to combat saddle sores, an occupational hazard. If anybody knew whether Armstrong had saddle sores, it would be his masseuse, O’Reilly said -- and he did not. She described the panic in the Armstrong bus about the positive test, until a servile world cycling federation accepted the doctor’s ludicrous note, and Armstrong pedaled onward. I alluded to the negated positive. It did not go un-noticed. That drizzly morning in Charleroi, Armstrong’s lawyer-manager, Bill Stapleton, sought me out as we enjoyed coffee and croissants before the day’s stage began. He pointedly told me that Lance had never tested positive. Yes, he did, I said, for steroids. That was not a positive test, he said. I understood his legal point but more important I realized, these people are serious, and they are going to fight on every point. We all know how that ended, years later, with Lance’s confession on Oprah. I think about him while watching the Tour. I saw him win his last three titles. He was the greatest rider of his time. I suspect just about all of them cheated. I hear he has downsized, in his own private St. Helena. Napoleon also held a staging area around Charleroi, 200 years ago. He had come back from exile and had re-claimed much of the French army and was convinced his decisions would always work out. He would feint one way, go the other way, and rout the English and the Prussians. . But they stood up to him, in terrible fighting, on the road north in an area known as Waterloo. In July of 2004, I spent several nights in a motel near the battlefield but never had time to visit it. I was reading “L.A. Confidentiel” and riding in a press car with two copains and getting the cold eye from Lance’s perimeter defense. As I sit here typing my little therapy blog – not in classic blogger underwear, I promise – I am supervised by a phalanx of editors.

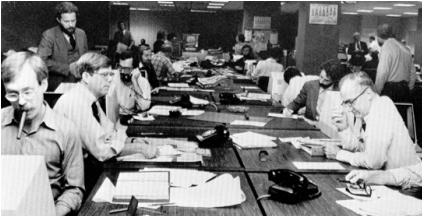

They perch over my shoulder, the ghosts of deadlines past, monitoring my every whimsy. Before I can push the “Submit” button on my site, I must satisfy editors who kept me tethered for all those decades. They suggest temperate phrases like “alleged” and “so-called” and “was said to be” for assertions I cannot totally back up. “You need to do this over,” I can hear Jack Mann or Bob Waters snarling at me in Marine patois when I was learning to play the game right at Newsday. “Ummm, that doesn’t read like Vecsey,” I can still hear a Times national-desk editor named Tom Wark saying to me about a long profile of a bank robber who had earned a degree behind thick federal walls. “Could you run it through the typewriter again?” What a wonderful compliment. “Ummm, could you make a few more phone calls?” I can hear Metro copy-fixers like Marv Siegel and Dan Blum, or Bill Brink in Sports, saving me more than once. And early on Saturday mornings, right on deadline for my Sunday column, I would get a careful final read from the superb Patty LaDuca (about to retire, for goodness’ sakes.) When I am talking to journalism students, one of my main points is that if you have an editor supervising your work, you are actually participating in journalism. But if you expect your precious words to appear in print just the way you wrote them, you are merely a blogger. Editors keep you from making an ass of yourself. And sometimes the best editor is….yourself. I was thinking about editors a month or two ago when a major movie studio allowed “The Interview” to come out with the premise of the dictator of North Korea having his head blown off. Charming. The self-indulgent director waved the “creative freedom” flag, and the studio heads folded, with predictable world-wide tremors. Movie directors and producers could use a reality check from an editor – “Ummm, could you look that up?” -- when making films like “Selma” and “Lincoln,” as Maureen Dowd pointed out on Sunday. More recently, a weekly satire magazine in France published a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, touching off horrible violence around the world – violence that surely had been waiting to be fomented by opportunistic lunatics. Then the staff came back with another cartoon of the prophet. Was any of that necessary? Journalists have this implanted in their brains at an early age, by editors. What are the consequences? What does the other side say? Those of us who learned to present all sides – to make a few more phone calls – are lucky. So are the people who read (or watch, or listen to) those increasingly rare sources. (I don't count Stewart or Colbert. I am talking about their sources. That is, journalists.) * * * One of the most rational posts on the Charlie Hebdo issue is by Omid Safi, the director of Duke University's Islamic Studies Center, for that great site, onbeing.org. http://onbeing.org/blog/9-points-to-ponder-on-the-paris-shooting-and-charlie-hebdo/7193 And here are a few others: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/10/arts/an-attack-chills-satirists-and-prompts-debate.html?_r=0 http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/unmournable-bodies http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/charlie-hebdo-shooting Wait a minute, that’s my city. I seem to be saying that a lot these days. Boston in 2013, London in 2005, New York in 2001, Sydney recently, and now the most beautiful city in the world. If you have walked a city for a few weeks, you have lived there, it is yours. The horror raised memories: The first time, my wife and I, still kids, wandering on the theory of $5 a day, back in 1966, criss-crossing the river, bridge by bridge, just because. Taking our children in 1976, five of us, walking to the Louvre on a chill April day, thinking, This is as good as it gets. Our friend Roby and his grandson David driving us to our hotel, seeing the lights flash by, Paris at night. Another friend had a corner apartment in a quiet district, a walkup, just high enough to feel we were looking out on an Impressionist painting. And the most recent time, a full moon, our pal had the top down, and we circled the Eiffel Tower around midnight, just laughing at how outrageously gorgeous it is. We know the block in Boston. Our London rellies live not far from the bus line the nihilists blew up in 2005. My wife knows the coffee shop in Sydney, a stopping point in her long walks in 2000. How could one not take it personally, when a few people hate so much that they could do this kind of harm? What do they hate? What do they resent? Paris is our city, built on the arts and the sciences of the Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the emerging Europeans. It shimmers for all of us. The faces on the BBC and Euro News are familiar, so is the language. It’s our home, too. So far away, I could only dig out the French national cycling shirt Roby gave me, 30 years ago. He was a national cyclo-cross champion in the 40’s, and later coached French cyclists. In 1982 he drove a few journalists on the Tour. When we had a question, he would pull alongside Bernard Hinault and ask why he was making his move at this time. Roby loved his country. The first time he came to the States, he saw the Washington Monument up ahead and he started to cry. “J’adore l’Amérique,” he said. Today I put on Roby’s jersey – it’s way too tight, from too many washings, too many races – but I put it on, and I thought, “J’adore La France.” (My friend in Rio, Altenir Silva, in the Comments below, recommends this clip from "Casablanca." I would add, let us also note Angela Merkel, front and center among world leaders, on Sunday.) In the last hours of the Tour on Sunday, I thought of the friend who taught me to love the sport.

So I went upstairs to get Roby’s old tricolor national-team jersey he gave to me after the Tour we shared in 1982. I hung the jersey by the television as I watched the riders make the normally ceremonial journey into Paris. I wear it only for special occasions – maybe a softball game or the five- mile Turkey Trot I used to run. I want the jersey to last. Roby Oubron was a four-time world cyclocross champion in 1937, 1938, 1941 and 1942, who was helping the Jonathan Boyer team during the 1982 Tour. Boyer had been the first American to race the Tour in 1981 – a forerunner to the Yanks who would later win the Tour. Roby was driving the car for Boyer’s manager Rob and photographer William and a Belgian camera crew (three guys known as Vandy). I was allowed to squeeze in for five days and immediately bonded with Roby who was squat and powerful and looked like Picasso. Although he had never ridden in the three-week road race that is the Tour, he had coached and mentored generations of French, Czech and blind cyclists – and was tight with Bernard Hinault, the Breton who would win the Tour that year. The car had access to the heart of the Tour. If I asked why Hinault was making a breakaway, Roby would gun the car alongside Hinault and chat with his pal, and then would report back to us in French simple enough for me to understand. Roby knew where to stop for a quick omelet during a long stage. He knew all the good bars for a quick beer in Bordeaux or the Pyrenees. He was at home with millionaire sponsors and rugged motorcycle messengers. He was one of the warmest, funniest, most communicative people I ever met. Roby had fought in World War Two, and had been injured and pulled off the battlefield by an American soldier. A few months after the 1982 Tour, Roby accompanied some Tour riders to a new race across Virginia – his first visit to the United States. I was in a car with him when we saw the Washington Monument, and I saw tears roll down his cheeks. “J’adore l’Amérique,” he said. He became my adopted uncle figure; he and his lovely wife Simone watched over our daughter when she was working in Paris; he gave me a jersey that had been worn by French cyclists; and we met every so often in New York or Paris. “Tu es un champion du monde,” I would sometimes utter in dramatic fashion, and he would chuckle. Roby passed in the late 80’s; I never got to say goodbye. But every year when the Tour comes around, I think of the old cyclocross champion who never rode the Tour, but helped me love it. * * * On Sunday Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the Tour and also dug up a great finishing kick to launch his countryman Mark Cavendish to win the stage -- a gripping end to this year's Tour. I celebrated the riders, the country, and Roby by putting on his jersey and hopping on my old-guy bike, and going for a spin. A morbid thought crossed my mind the other morning while I was transfixed in front of the tube.

No matter what, the Tour de France is going to end on Sunday with the ceremonial ride up the Champs-Elysées, and then it will go away for the next 49 weeks. Why does it have to go away? The Tour catches my attention like no other sports event; I’ve covered parts of six or seven, sometimes driving the course just before or just after the riders. Now I watch the live show on NBC Sports Network every morning (Tuesday is a rest day.) as the cyclists flit from mountain to coastline, from country to city, always something different around the next turn. The riders all look alike, with their thrust jaws and wraparound shades and wiry physiques hunched aerodynamically. For the viewer, the cyclists come to individual life through the expertise of Paul Sherwen and Phil Liggett, two Englishmen who have been broadcasting the Tour since humankind invented the wheel. They know all 198 riders registered for the Tour and, as the day’s race unfolds kaleidoscopically, they discuss which rider is a sprint specialist and which one a mountain man. One thing is certain: the Tour endures despite the retirement and current legal troubles of Lance Armstrong. Whatever he was doing chemically, we all saw him whup a bunch of riders who actually did test positive. He was a great force but he is long gone now. And the land and the riders remain. As seen by camera from a Tour helicopter, a knot of riders banks to the left around a curve on one rainy desolate section of country road. In the background are sheep or maybe one tent pitched in a field. A couple stands by the wayside, clapping politely. The mind snaps the picture and the camera rolls around the next bend. While the network breaks for a commercial, the camera may focus on a crumbling hilltop castle. Here is the ultimate truth about the Tour de France: the star of the show is one of the most beautiful and diverse and historic countries in the world. I know, I know, one does not need the Tour to drive through Normandy or down the Rhone valley or across the haunting Massif Central. (I tremble as I type that name.) For three weeks a year, the network brings France into my house. I try not to dwell upon that grim moment, coming next Monday, when the Tour goes away. When I took the buyout from the New York Times last December, a few people asked if there was anything I regretted not doing.

I had to pause. I could think of a few legendary college football stadiums, a few arenas or ballparks, some great soccer stadiums in Latin America and Europe. But events? Then something popped into my mind: Paris-Roubaix. http://www.bicycling.com/news/pro-cycling/tom-boonen-powers-fourth-paris-roubaix-victory-equals-record If there was one unique sports event I had never covered, one exotic specialty I had not witnessed in person, it was the trek from outside Paris to the cycling-mad town near the Belgian border. The chief attraction is the roadway itself – multiple sections of cobblestones put in place during the Napoleonic Era, state of the art then, torture to human and machine nowadays. I have grown to love cycling, covering the last tumultuous years of Lance Armstrong’s reign. Some of my best days were spent in a car with Sam Abt, the Times’ long-time cycling correspondent, and James Startt, photojournalist and cyclist and musician based in Paris. James would drive, and Sam would smoke, and they would bicker over whether the CD would blare reggae (James) or punk rock (Sam, go figure). James is still plying his trade, as anybody can tell from clicking on Bicycling.com. He recently found one of the most obscure winners of the Tour, Roger Walkowiak of France, whose stunning upset in 1956 annoyed the French fans because (a) he had a Polish name and (b) he was not a favorite and (c) he employed tactics like preserving his strength by riding in the pack on key stages. No panache. Walkowiak made very little money from cycling but used it to buy a sheep farm in southwest France, and has remained mostly incognito ever since. Somehow, Startt cajoled Walkowiak into granting an interview that casts a deep look into the history and mentality of this fascinating sport. You can access it: http://www.bicycling.com/news/featured-stories/lamentation I was hoping my friend Startt, a former American cycling hopeful, would get to ride the Paris-Roubaix course ahead of the big race on Easter Sunday, but it didn’t work out. Instead, he and his camera were there when the cyclists arrived in the bustling oval in Roubaix. Also, the new NBC sports channel carried the last two hours of Paris-Roubaix, live, with the same phalanx of planes, motorcycles and cars used in the Tour, plus good old Liggett and Sherwen doing the commentary. I could sit in my living room and watch the best cyclists in the world try to avoid being maimed by the cobblestones of Flanders. That epic, singular race was described last week by John Leicester, the Associated Press European sports columnist. I won’t even try to go over his superb description and reporting: http://sports.yahoo.com/sc/news?slug=ap-johnleicester-060412 The sections are called pavés. I had seen them up close during one stage of the 2004 Tour de France, which meandered from Liege through the killing fields of World War One, and into France. I remember watching the team trial go past on a rainy, windy day, hardened Tour cyclists quivering from repeated shocks to spines and central nervous systems from hitting one 18th Century cobblestone after another. The cameras were so close you could see the reinforced bicyles shimmy and shake. It hurt to watch. The weather Sunday was cool and damp. People were bundled up along the narrow lanes, waving at the cyclists from inches away.(Why are there not more accidents?) I saw quaint villages and the green fields of Flanders in early spring. I was comfortable in my house, but could sniff the coffee and the frites. I would have loved to be transported to chilly Roubaix, listening to survivors grouse and marvel at this cruel test. I could only adapt the Passover saying: instead of Next Year in Jerusalem, I said, Next Year in Roubaix. It’s a thought. |

Categories

All

|