|

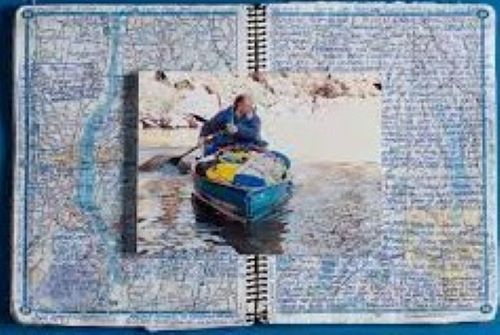

A 300-pound man is gliding down the river in a canoe. His appearance, his shabby belongings stuffed into every corner, are straight from the last thousand homeless people you saw, under the bridge, on the subway bench. But Dick Conant did it differently. He had the intellect and knowledge of the med-school applicant he once had been. He could paint. He carried hard-covered books in his canoe, and some days he just lazed by the river and read. He also could read the river, could decipher the maps, could extract knowledge from other riverman (and more than a few riverwomen) he met on his missions along the Intracoastal. People on the banks, people seeing him lug his jumbled belongings through the streets, stopped to talk to him, were stunned by his intellect, by his knowledge, and also by his tales of a girlfriend named Tracy waiting for him back there somewhere. People never forgot him. America – free-falling into cruel anarchy these days – is built upon wanderers. It’s in our blood. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn and Jim. Daniel Boone and family making their way through the Cumberland Gap in 1769 as if it belonged to them instead of the natives. Lewis and Clark, ditto, toward the Northwest. John Ledyard’s canoe trip down the Connecticut River from New Hampshire – in 1773. The guy hitch-hiking on Route 66, singing to himself, a regular Chuck Berry. Dick Conant struck a chord. Sometimes the people on the riverbank, meeting this strange hulk, ingesting hot sauce the way other people suck on a Tic-Tac, grew quiet, as if confronting some inner wanderer. Hmmm, they thought. Hmmm. That’s what Ben McGrath, a writer for the New Yorker, thought a few yards from his home on the Hudson River, where the Dutch once encountered the Lenape. McGrath was fully nested, job, wife, growing family, but he was fascinated by this articulate and charismatic giant who secured his canoe near McGrath’s backyard. Hmmm. In the interests of journalistic/literary curiosity, McGrath chatted him up, and vice versa. And when the big man pushed off, McGrath went with him, in a way. Dick Conant was canoeing downriver for perhaps the last big jaunt of his wandering days, and McGrath tried to stay in touch. Then one day on a bad stretch of North Carolina river, the canoe turned up, but not the man. An authority found McGrath's name scribbled on a river map and called him, and McGrath wrote a haunting piece for the New Yorker. He was now into it, big-time, collecting every name and phone number and e-mail address Conant had scribbled somewhere. The only name and address missing was that of Tracy, the lost love Conant always said was waiting for him back in Montana, or somewhere. Now, McGrath has written a touching book entitled “Riverman: An American Odyssey,” recently published by Alfred A. Knopf, including photos of Conant, and photos of a few of his paintings. How did a college soccer player (Albany State) come to be most at home on rivers? McGrath writes about the large and complicated Conant family (he likes every Conant he meets) and all have their version of what happened to kid brother Dicky: too many drugs, too much booze, the late 60’s. (The book is worth it for the meeting at Woodstock between Dick Conant and Jimi Hendrix.) There is a one-sentence allusion to the young boy's quick exodus from a church summer camp: inexplicably, McGrath lets it sit there for many chapters before another quick allusion or two as to why Dicky left that camp, and never seemed the same. That human mystery aside, “Rivertown” is a touching ode to all river towns, most of them falling apart, a century past their prime, but inhabited by people still in touch with the water rushing past. I’ve known rivers (see below): Hannibal, Mo., two visits in the late ‘50s: Louisville, Ky., when my young family rode our bikes alongside the Ohio; as a news reporter, accompanying ecologists on a canoe glide on the Youghiogheny, a tributary of the Monongahela; Uncle Harold Grundy’s cottage in Bath, Maine, a few steps from the Kennebec he had dredged before WW II -- I never appreciated river towns as much as I do now, via the mobile Conant. McGrath solves no mysteries. He writes that Conant either sighted or imagined Tracy, a latter-day Dulcinea, an American Beatrice. Conant drank and danced gracefully in river-town bars, telling people how he was soon going soon to be with Tracy; women were charmed by his eloquent faithfulness; but he never got back. (Unless he’s there now.) ("Cathy, I'm lost, I said, though I knew she was sleeping ("I'm empty and aching and I don't know why." --- "America," Paul Simon.) McGrath writes the book half expecting Conant to ring him from some river town and fill him in on the empty canoe, about his recent adventures. The alternative is to slip onto the river in a suitable craft, just to see what’s out there. *** From the classic poem by Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," Gary Bartz has recorded his version: “I’ve Known Rivers.” I was trying to figure how to express thankfulness, and fortunately others have done it for me.

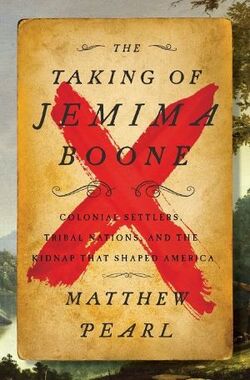

On Wednesday’s editorial page of the New York Times is a lovely essay by Tish Harrison Warren, an Anglican priest. (“This Year, Exercise Your Thankfulness Muscles”) Her fifth and last suggestion was “Take a gratitude walk,” about her young daughter who “invented something called the Beautiful Game,” finding sights that touch the heart. My responses to her essay: SIGHT 1: Fall Colors: I lifted my eyes off the printed page and saw the northern sky outside our home, with autumnal trees. Even though some people are figuring out that trees are vital in the struggle to save the planet, trees nevertheless are under attack in traditionally leafy suburbs like ours. The Town of North Hempstead, which pretty much allows leaf blowers and tree choppers to spew gas fumes and dust, making our suburb feel like an airport runway, is fretting over trees getting lopped off. These privacy-giving autumnal colors above are on our property, and we are grateful. SIGHT 2: A Young Nurse: The other day I had a common procedure as an outpatient at Glen Cove (Northwell) Hospital. The young nurse who prepped me was getting married – three days later. When they shooed me out a few hours later, I could still remember, over her mask, the glow of her eyes. I was thankful for skill, and youth, and hope. SIGHT 3: A Crowded Restaurant: The other evening, I took a walk around our town and slowed down outside Gino’s on Main Street. Since my wife sussed out the pandemic early in 2020, in our caution, we have not eaten out – not a terrible loss because she is such a good cook – but there are familiar places we miss in our town: Diwan on Shore Rd. and DiMaggio’s on Port Blvd. and Gino’s. I peeped in a side window at Gino’s and saw every table and every booth filled, the staff moving fast, and I hallucinated about a Gaby’s salad and a daily special and those hot chewy rolls and the cheesecake a la nonna for dessert. We’ll be back soon, I keep saying, but in the meantime I am thankful for the bustle at Gino’s. SIGHT 4: Books About Thanksgiving. I am currently reading “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer, about very different strains of English immigration in the New World. I never fully understood what it meant for settlers to call their new home New England – but as I watch a very divided country display major stress faults, I am more thankful than ever for the “New England” emphasis on education, producing a high level of literacy and study. May it prevail. As the U.S. Thanksgiving loomed, I took another book off our shelves, “Mayflower,” by Nathan Philbrick, who tries to re-create the fall of 1621: We do not know the exact date of the celebration we now call the First Thanksgiving, but it was probably in late September or early October, soon after their crop of corn, squash, beans, barley, and peas had been harvested. It was also a time during which Plymouth Harbor played host to a tremendous number of migrating birds, particularly ducks and geese, and Bradford ordered four men to go out “fowling.” It took only a few hours for Plymouth’s hunters to kill enough ducks and geese to feed the settlement for a week. Now that they had “gathered the fruit of our labors,” Bradford declared it time to “rejoice together…after a more special manner.” The term Thanksgiving, first applied in the nineteenth century, was not used by the Pilgrims themselves. For the Pilgrims a thanksgiving was a time of spiritual devotion. Since just about everything the Pilgrims did had religious overtones, there was certainly much about the gathering in the fall of 1621 that would have made it a proper Puritan thanksgiving. But as Winslow’s description makes clear, there was also much about the gathering that was similar to a traditional English harvest festival—a secular celebration that dated back to the Middle Ages in which villagers ate, drank, and played games. Countless Victorian-era engravings notwithstanding, the Pilgrims did not spend the day sitting around a long table draped with a white linen cloth, clasping each other’s hands in prayer as a few curious Indians looked on. Instead of an English affair, the First Thanksgiving soon became an overwhelmingly Native celebration when Massasoit and a hundred Pokanokets (more than twice the entire English population of Plymouth) arrived at the settlement and soon provided five freshly killed deer. Even if all the Pilgrims’ furniture was brought out into the sunshine, most of the celebrants stood, squatted, or sat on the ground as they clustered around outdoor fires, where the deer and birds turned on wooden spits and where pottages—stews into which varieties of meats and vegetables were thrown—simmered invitingly. In addition to ducks and deer, there was, according to Bradford, a “good store of wild turkeys” in the fall of 1621… The Pilgrims may have also added fish to their meal of birds and deer. In fall, striped bass, bluefish, and cod were abundant. Perhaps most important to the Pilgrims was that with a recently harvested barley crop, it was now possible to brew beer. Alas, the Pilgrims were without pumpkin pies or cranberry sauce. There were also no forks, which did not appear at Plymouth until the last decades of the seventeenth century. The Pilgrims ate with their fingers and their knives (117-118). * * * I am also thankful for readers of My Little Therapy Site, who contribute so much. Coming soon after Diwali, and with Chanukkah and its celebration of life following so closely, can you share any thoughts about thankfulness? * * * (With thanks to the website Reformation 21, Lancaster, Pa., for the excerpt from the Philbrick book: https://www.reformation21.org/about-reformation21 With thanks for the essay by Tish Harrison Warren: www.nytimes.com/2021/11/21/opinion/thanksgiving-gratitude.html?searchResultPosition=1ition=1  As soon as the final out settled in Freddie Freeman’s glove, I felt a surge – not quite the relief I felt when the Covid vaccine arrived in my arm but rather the excitement of a great swath of free time, suddenly arriving. Book time. I wasn’t reading hard-covered books during the warm months, but I kept taking notes about books I wanted to read. Now, no more long evenings obsessively watching the hapless Mets organization fall apart, in the person of Jacob deGrom’s pitching arm. Now, World Series over, free at last. The first book has been “The Taking of Jemima Boone,” by Matthew Pearl, about the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s most spirited child, on July 14, 1776. I was drawn to the subject because Daniel Boone was all over Kentucky when I lived in Louisville for two years, as the Appalachian news correspondent for the NYT, wandering the region. Boone's statue and name were all over the Commonwealth of Kentucky, as I drove on twisting roads that had been paths for him to explore, to hunt, to escape. But somehow I never wrote about him in all the time I roamed around Kentucky. Now Matthew Pearl, a novelist by trade, has written a taut drama, with a thick index in the back, assuring me that he was using source material and not only his novelist’s imagination. It’s a tricky time to be catching up on an American icon, most known for barging into Native American territory, often fighting for land, as well as for his life. The U.S. is re-evaluating its memorials to slave-owning Confederate generals, as well as explorers like Columbus. What to do about Daniel Boone? The reason Jemima Boone and two other girls in their early teens became prisoners is that Daniel Boone could not, would not, stay in coastal towns but pushed west through the Cumberland Gap and on, losing a son, driven by a tropism for space and land and “freedom.” This American icon was taking other people’s land -- at gunpoint – but his relationship to the people of the land was more complicated than that. He became part “Indian” in style and spirit. He was captured by a complex chief, Blackfish, who adopted Boone as a son, and recognized him as a kindred soul, with skills and courage. Boone, of course, was planning his escape. The actual “taking of Jemima Boone” occupies the taut first 75 pages of this book – how she tried to fight off the men who surrounded their canoe, how she left signals for the man she knew would come looking for her, and how she bonded, in a way, with the son of Blackfish, who treated her with respect, by all versions. Pearl, the novelist, resists going too far in suggesting a romance between captor and captive. In fact, one of the things I have learned from recent reading about New England settlement is that Indian males almost never raped, although some did “marry” their captives. It never came to that in this Kentucky encounter, but the details seem to have survived (with revisions, with exaggerations, surely) into the 19th Century, and then the 20th, and now the 21st. Matthew Pearl makes it real. Daniel Boone kept going, all the way to Missouri, where he and his wife Rebecca and Jemima Boone all died – of old age. He has two graves, one in Missouri, one in Frankfort, the Kentucky capitol. I recommend “The Taking of Jemima Boone” as a well-written and well-researched visit to a distant time, leaving complexities in a nation now re-examining (at long last) its myths and heroes.  I rarely read fiction these days; so much to learn from non-fiction. In spurts of reading, I have belatedly learned about Neanderthals and evolution and DNA, as well as the earliest “settlers” of New England. This has been spurred by my wife’s vast personal research in the genealogy of her family, from England and Scotland. Next in my reading list: “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer I was drawn to the book by a review by Joe Klein in The New York Times, with this overview: “Albion’s Seed” makes the brazen case that the tangled roots of America’s restless and contentious spirit can be found in the interplay of the distinctive societies and value systems brought by the British emigrations — the Puritans from East Anglia to New England; the Cavaliers (and their indentured servants) from Sussex and Wessex to Virginia; the Quakers from north-central England to the Delaware River valley; and the Scots-Irish from the borderlands to the Southern hill country. I consulted the index and found this one reference: “When backcountrymen moved west in search of that condition of natural freedom which Daniel Boone called ‘elbow room…’” Do these four separate waves of emigration explain why the United States, perhaps more than ever, seems to be several different countries, with rival impulses and outlooks? Does it explain Red and Blue states or regions? I look forward to learning what Fischer has to say.

Diwali, Trafalgar Square, 2020 Diwali, Trafalgar Square, 2020 When Kim Ng, of Chinese descent, was appointed general manager of the Miami Marlins on Friday, she became the first female to hold that role in top American sports. Americans like to congratulate ourselves on being the land of opportunity, which it has been, although under duress from our child-kidnapper-in-chief in the past four nasty years. When voters elected Kamala Harris, part Jamaican, part Indian, and female, as the vice president nearly two weeks ago, this was cause for celebration in the U.S. -- although not by militia-type worthies with rifles on their hips who came out of the woods to help "supervise" the polling. As for the rifles -- only in America. Oddly enough, this opportunity stuff goes on in other countries, too. Currently in London, under the leadership of Mayor Sadiq Khan, of Pakistani ancestry, large-scale celebrations of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, are being held in public places. This is not new. Two decades ago, my wife and I were in London (for a Giants football game!) when we ran into a modest Diwali celebration, some music, some dancing -- and we saw four female police officers, in classic bobby uniform, dancing along with the celebrants. Only in London. Canada has its own share of vibrant minorities. I was reminded of this in the Saturday NYT in a touching profile of an orphan, from India, who lobbied his way to adoption in Toronto and now runs a high-end restaurant there. When he was 8, Sashi was a street kid, abandoned, taken into a home in Tamil Nadu, operated by a small Canadian outfit, Families for Children. There are places like that all over India. My wife, Marianne, used to escort children from Pune to the U.S. for pre-arranged meetings with their adoptive families. ("I am the stork," was her motto. I think her total of kids was 24.) The U.S. was not the only country involved in adoptions. Canada was, and Norway had a large presence in India. Children in these orphanages know what is going on: they are on display. They are not shy about asking foreign visitors: "Take me with you." (My wife still talks about the sadness of a girl, heading to her teen years, who had realized she was not being adopted.) But as Catherine Porter writes in her poignant story in the NYT, young Sashi, with the desperation of a survivor, spotted Sandra Simpson of Canada, a return visitor to the orphanage, and he persuaded her to take him to Toronto and adopt him into her large brood. How Sash Simpson became a top chef, four decades later, is a tribute to his drive to get in the back door of a restaurant, and do any job, and keep learning. He made his own luck, with the help of the Simpson pipeline, and others. His restaurant -- Sash -- is hurting during the pandemic, but he gives the impression that he forced his way this far, and will survive. Only in Canada. Then there is Ireland, where Hazel Chu, of Chinese heritage, has become mayor of Dublin, replacing Leo Varadkar, of Indian heritage, the first gay mayor of Dublin. With my Irish passport (courtesy of my grandmother), may I say: "Only in Ireland." “I suspect that seeing NYC burn arouses strong feelings in you,” writes a friend from Queens, long living overseas.

* * * We sat in our den with a visitor from Moscow and watched smoke pour out of the Parliament building. This was October of 1993; our friend was frightened because her son was a journalism student in Moscow and she knew he would get up close, to observe, to report, maybe to protest. Now it is our turn. My wife and I sit in the same den and watch our country – places we have lived and visited – quiver with rage. One over-reaction and we could have Moscow-on-the-Hudson, Tienanmen-Square revisited. I feel the way our friend must have felt that warm autumn day when she watched smoke rise above the Moskva River. New York is my hometown and it’s in my blood, ever since my father took me around, teaching me names and histories. I still see New York through the prism of being 5 years old and watching Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an old white wizened president, campaign through Queens in an open limo during a cold drizzle, or being 7 and having my father call from the office and say our team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, had just signed Jackie Robinson. I see New York from memories of gentle folk, bootstrappers from Queens, who met sometimes in my family living room, in a discussion group strictly maintained at a 50-50 black-white ratio. So many white people have lived more comfortable lives because of the enslavement of so many black people. We can’t get past it. It would be interesting if we could go back in time with those nice people, long gone, and in 2020 terms discuss America’s Original Sin. Now, from my safe perch in a nearby suburb, I feel viscerally sick when I see video or photos of broken windows, burning cars, confrontations. People are expressing their horror at the murder, caught on a smartphone camera, of George Floyd by four police officers in Minneapolis. I feel proud of the Americans who have flocked, mostly in peace, to express their believe that Black Lives Matter. The Floyd family has cited religion to score violence and revenge, but this is not a cool time, and I know there are bad actors, white and black, who want to cause anarchy and fear. The rock-throwers and the window-breakers will give racists a chance to break heads in the name of law and order. (Tom Cotton, you old op-ed sage, I’m talking about you.) I’ve been lucky to travel all over the States -- Minneapolis-St. Paul, Atlanta, Seattle, LA, Chicago. For two years in the early 70s, we lived, on assignment for the Times, in Louisville, Ky., -- five homesick New Yorkers nevertheless blessed with two stimulating years. The other day, from Louisville, I saw a story that gave me hope, or rather temporary hope – a human chain of white women at the front of a protest, ahead of black protestors, sending a physical and emotional message: “We got you.” Our next-door neighbor in Louisville would be so proud of these protestors. Rabbi Martin Perley had built bonds with the African-Americans of the 60s, so that when Louisville seemed ready to go up during a protest, he joined other civic leaders in walking the city’s West End, urging people not to take out their rage on their town. So I was proud of the white women of Louisville who went up front, but then I read about the police shooting of a well-known BBQ merchant on the West End, who may have fired a pistol in response to looting outside his door. So we’re back where we started with George Floyd. Now it is our turn in the TV den to watch nightly confrontations in New York. I spy a street or building or bridge and know exactly where it is. I have walked there and chatted with fellow New Yorkers; I have ridden the buses and subways; I drive comfortably all over my hometown. In my home borough of Queens, the Cuomos lived 10 blocks to the east of my family and the Trumps lived 10 blocks to the west of our busy, noisy street. Most days, Cuomo is hectoring New Yorkers to stay smart about social distancing and keeping an eye on the bumblings of the mayor. On Friday that disturbed and dangerous president brayed that George Floyd would be so proud of the big stock-market leap. What a jackass. Trump is the Republicans’ kind of guy. We are all paying for the anarchy and hate and stupidity he has emitted. Still, I take hope when I see blacks and whites, Latinos and Asians, mostly young, demonstrating their idealism, while we sit in front of the tube, like our friend from Moscow once did. “Call a person over in Venezuela,” blustered the man with the orange goo slathered on his face.

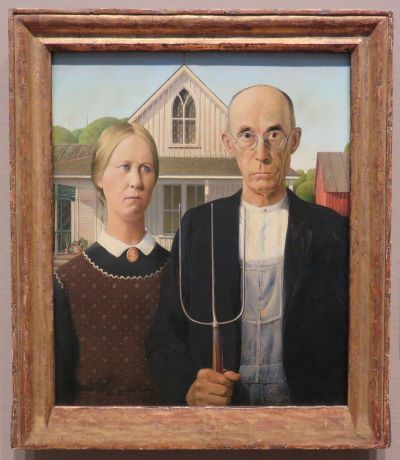

“Ask them how did nationalization of their businesses work out? Not too well." The Dear Leader was responding to questions about why the American government was not mobilizing businesses to make the masks and respirators needed for endangered health-care people to care for endangered patients. He’s all for Congress supplementing his friends in big business in this crisis. He just doesn’t want to tell them what to do with the money. This in a country that mobilized auto plants to produce airplanes during World War Two, as David Leonhardt recalled in the NYT on Monday. This in a country where hospitals are begging people to donate masks and other medical goods they are “storing” in their homes, in order to save the actual sick, until The Orange Guy thinks of something. Ordinary citizens are sewing masks in their homes, patriots in the old style, because the federal government cannot get a handle on this. I immediately thought of an entitled woman I met in Cuba, making soap in her own kitchen. I said “soap,” not “soup.” I met the woman when I covered the Pan-American Games in Havana in 1991. A friend in New York had told me about her, a talented woman who had gone to school in the States, had a medical background, whose husband, a high-ranking officer, had fought and died for his country. She was eager to be my guide to the complicated world of Cuba, when I was not directly covering sports issues during the Games. She was loyal to the country and she knew how things worked, and did not work. She had a car, one of those classic 50s cars, in good shape, and took me around Havana as well as the Bay of Pigs, where her husband had served. For a sense of how people lived, she took me to her building, in a genteel if fading neighborhood. The lights were out on the stairway. The apartment was roomy, if dated. They had raised their family there, and now some members were doctors, working in the state hospital. She pointed at the stove, at a pot of soap slivers in water, waiting for her children and their spouses to bring home more soap remainders from the hospital, so she would boil them down, sanitize them, turn them into something approximating soap bars. “I’ve become my own grandmother,” she said. I think of her remark and those soap scraps now that Americans are begging the federal government to supply the goods to keep them alive. I think of our portly poseur, who has fooled some Americans into thinking he has business sense, any sense at all. He wants American money in the hands of Mnuchin and other gunnysack cabinet members rather than in the hands of the people who do the work. He’s not going to induce American enterprises into making make goods needed by endangered people. Medical people are begging for equipment, but this is not his department. He has his principles. He rolls over and plays nice for Putin and Kim but he talks big about Venezuela. His instincts are toward one-man rule. On Monday it seemed he had disappeared Dr. Anthony Fauci, an authority on the virus who lately has been verbalizing some of his concerns. Fauci was missing from the press conference Monday, like some Politburo big shot who had been airbrushed out of a group photo. Maybe Fauci would return on Tuesday. To be continued. In the meantime, thank goodness we are not a third-world country like Cuba, like Venezuela. * * * Trump’s Venezuela babble: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/03/23/819926854/fact-check-trump-compares-defense-production-act-to-nationalization David Leonhardt’s riff on mobilization before World War Two: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/22/opinion/trump-coronavirus.html?searchResultPosition=4 * * * QUESTION: A friend asked me yesterday if he could be put on my email list for my occasional rant. I said there is no such mailing list; I put my precious little ramblings out there on the Web like a message in a bottle, tossed out to sea, and hope people find it. Only rarely do I send something directly to a friend. Could I get a show of hands from anybody who would like to be on a totally-anonymous and confidential list for these occasional pieces? Thanks. My email is: [email protected] NB: Comments here are welcome. Nay, beseeched. GV. (The following ode to Iowa was written before all hell broke loose in the ramshackle "system" that was supposed to collate the Democratic caucus results Monday night. Even before the network failed to produce while the world was watching, visiting savants like Chris Matthews were questioning -- in front of the earnest citizens -- why Iowa got to hold the highly visible first "primary" scrimmage every four years. With these reasonable questions being raised, Iowa may lose its prominent spot. Shame. There ought to be a place for well-meaning Americana -- but maybe not with an ignorant and vicious wannabe dictator getting a free pass from his party enablers. Poor Iowa, caught up in the tumult. My original praise for Iowa and skepticism about a caucus:) They are highly motivated, conscientious American citizens. But what in the world are they doing? Why don’t they just vote? Then I remember, Iowa is different, or so they say. I’ve been there three times and liked all three visits. (More in a bit.) While trying to make sense of this caucus thing Monday evening, I remembered one of my favorite musicals – “The Music Man,” by Meredith Willson, that’s with two L’s, and don’t you forget it. A con man (Robert Preston) gets off the train in River City, Iowa (Willson was from Mason City) and tries to chat up the townspeople, only to receive a bunch of double talk, some of it polite. The result: “Iowa Stubborn.” That charming character trait emerged Monday in snow-covered Iowa (or “I-oh-way,” as some of the denizens insist.) “The caucus is like cricket,” I told my wife. (We once saw the great West Indies team play a tuneup in a Welsh country town.) “Cricket is easier,” she said, meaning – bat, ball, tea. This caucus thing determines who wins the delegates, who has the momentum, or maybe not. It’s a portrait of Iowa. The Grant Wood painting, American Gothic. I am affectionate about Iowa – after first noting that its populace does not at all resemble that of my home town of New York. My first trip to Iowa was in 1973 when Charlotte Curtis, the great Family/Style editor of the Times (herself a Midwesterner), sent me out to Iowa to write about a boy, 18 or 19, who had just been elected mayor of a little town. (I cannot find the story in the electronic files.) It was such a nice visit, at this cold time of year, as I recall. My second trip to Iowa was early in 1979 when Iowa was selected as one of the sites for the first American visit by Pope John Paul II, because of the huge farm preserve, judged a perfect site for the man from Cracow. After scouting out Des Moines, I had dinner with a couple who had met when he was posted to her town in the Altiplano of a South American country. We went to a Chinese restaurant, where they chatted with the staff in Spanish – a big Chinese contingent, emigrated via Latin America. My third trip to Iowa was on a perfect autumn day in 1979 as the square-jawed Pope strode the plains, waving to a bunch of Lutherans. He was young and strong, looking like a former linebacker for the Iowa Hawkeyes. I edged closer to get a look – and got blind-sided by an American Secret Service guy. When the Pope had moved on, I stood on the great plain and congratulated the nun who had facilitated the press visit. She was so happy that the day had turned out so beautifully that I could think of only one thing to do – I hugged the nun. That’s what I think about whenever I remember that day. Oh, one other Iowa impression: Our daughter Laura decided to spend her junior year abroad and chose Iowa City. Every few weeks the phone would ring and a plaintive voice would say: "It's dark out here."  "American Gothic," by Grant Wood. From the Art Institute of Chicago. My feet can find it whenever I climb the front steps. "American Gothic," by Grant Wood. From the Art Institute of Chicago. My feet can find it whenever I climb the front steps. Now, every four years, the great journalists from my cable-network-of-choice wander all over that state and I thrill to every coffee klatsch and every barber shop. The journalists can explain “quid-pro-quo” and “impeachment” perfectly, but they cannot explain what those folks are doing on the first Monday in February. (The aforementioned Laura watched caucus news from Iowa Monday night and texted us: "Nicolle and Rachel far better than Troy and Buck." Poor girl is having Super Bowl flashbacks.) Maybe Meredith Willson could have explained the caucus, but he was more interested in the busy intersection of chicanery and romance, and bless his heart for that. The other day we saw a gripping American play, about dishonesty.

It made me think about: --- The current baseball scandal? --- Boeing? --- The former representative going away for insider stock selling? --- “Politics.” --- All of the above? The play is “All My Sons,” written by Arthur Miller in 1947 about a Middle American factory that shipped flawed parts for planes during World War Two, with disastrous consequences – first for the pilots, then for the people who ran the factory. We saw the play on the screen at the Kew Gardens Cinema in my home borough of Queens, part of the National Theatre Live series, at movie houses all over the world. We caught the play while the baseball scandal continues to unravel, at the cost of dishonored championships, ruined careers and realistic suspicions about other aspects of Major League Baseball – supersonic balls in orbit last season, plus Commissioner Rob Manfred’s threat to blow up the historic network of minor-league baseball. Baseball’s grubby face was on my mind as we went to see the important American play from the landmark Old Vic in London. The two leads were Americans: Sally Field, as a midwestern Mother Courage trying to keep the lid on her cover story, warning her husband to “be smart,” and Bill Pullman, with his large, open, American male physicality, reminding me of the aging Ted Williams. The rest of the cast is British -- terrific actors sometimes a tad off in American inflection or body language. The back-yard setting is a bit too folksy, post-war middle class, for a family with a factory that prospered during the war. But you get into it, way into it. The older son disappeared in aerial action during the war. The younger son is trying to live in the vacuum of loss. And the family that used to live next door has been broken by the jailing of the other partner for malfeasance with the faulty parts. As we sat in the movie house in Queens, we thought about Boeing, with its two new planes that crashed recently, killing hundreds of people, followed by superb reporting in The New York Times about wretched management and disgruntled workers who knew the planes were flawed. But the planes had to be delivered so shareholders could have a a new vacation home, a new luxury car, a new wife. How American. How courant. Money is at the core of the play. The father takes over the stage (all arms and shoulders, like Ted Williams giving batting tips) as he tells his son (returned from combat) that he has held the factory together so he can pass it on to the son, who is known to neighbors as idealistic. There will be money. That very day, in upstate New York, former Rep. Chris Collins was sentenced to 26 months for passing along inside information that a stock he had championed was about to fall apart. Collins, in tears, said he broke the law for his son, so there would be money, for the family. My wife and I sat in our favorite movie house, watching Arthur Miller’s post-war statement take very human form. My eyes teared up as I watched these very real people – the older couple trying to “be smart,” the son trying to make it all right by marrying the girl who used to live next door. When we left the movie house, in the funky old section of Kew Gardens, it was 2020, not 1947. Impeachment was in the air. People were still sending flawed airplanes into the air, all in the name of family. The American dream. Arthur Miller would feel right at home. * * * National Theatre Live website: http://ntlive.nationaltheatre.org.uk/ Guardian review of "All My Sons." =https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2019/apr/23/all-my-sons-review-old-vic-london-sally-field-bill-pullman-jenna-coleman Former Rep. Chris Collins sentenced to 26 months: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/nyregion/chris-collins-sentencing-prison.html?searchResultPosition=3 Tyler Kepner's latest great piece on the Houston Asterisks: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/18/sports/houston-astros-cheating.html?searchResultPosition=1 Recent article on suspicions by Boeing workers, by Natalie Kitroeff: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/business/boeing-737-messages.html?searchResultPosition=4 I am thankful for the Wampanoags who flocked to the Plymouth settlement in November of 1621 when they heard white people firing off their guns, and stayed three peaceful days to partake of the “feast.” Nobody spoke of “thanksgiving,” but rather a celebration of survival. Tribal ways were more complex than most people today know; the Narragansetts in what became Rhode Island welcomed Roger Williams, banished from Massachusetts for his inclusive Christian beliefs. All the “Indians” deserved better than the genocide that was coming down on them. I am thankful for the Americans who arrived as slaves in shackles and were treated cruelly. I am thankful for the modern-day Africans who flee failed societies and continue to add talent and energy and spirituality to the United States. I am thankful for the Latino people in my part of the world, who do the hard work that immigrants always do. In recent months we have had painters, gardeners, plumbers’ assistants and a mason’s assistant around our house, most of them quite willing and skillful. Their children speak colloquial English and contribute in the schools; some are going to college – the American dream. I am thankful for the immigrants who served in the military, many of them on the promise of citizenship for their contributions. I am sickened by a country that welshes on its promises, both domestic and foreign. People come to America in hope, the way the “pilgrims” did, and their children are put in cages. I am thankful for some of the best and brightest in this country, who left their homelands, escaping the Nazis or the Soviets, for what America said about itself -- the promise of education and opportunities and honest government. I am thankful for the true believers who testified in Congress in recent days, speaking of their hope in America. Some of them are Jews, like Marie Yovanovich and Lt. Col. Alexander S. Vindman,, who served so diligently and speak so eloquently about this country. Lt. Col. Vindman acknowledged his father for bringing the family from Ukraine to America, saying: “Here, right matters.” They should put his saying on the next new dollar bills. For their pains, Yovanovich and Lt. Col. Vindman have heard sneering overtly anti-Semitic sentiments from some of the “patriots” in government. Shades of Father Coughlin in the ‘30s, Roy Cohn (Donald Trump’s mentor), with Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the ‘50s, and Richard Nixon blaming the Jews during his last days in the bunker in the ‘70s. In America, it never goes away. Finally, I am thankful for Dr. Fiona Hill, a non-partisan government expert on Russia, and an American by choice, a coal-miner’s daughter from Northeast England with a Harvard degree. (Having helped Loretta Lynn write her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” I heard Dr. Hill’s background and said, “They are messing with a coal miner’s daughter. Not a good idea.”) Dr. Hill caught everybody’s attention by speaking so knowledgeably in what sounded like the finest British accent to our unsophisticated ears but which Dr. Hill termed working-class. She besought the legislators not to swallow Russian propaganda. The Republican firebrands seemed to know they were outmatched; a few panelists scampered to safety. One of the remaining Republicans, Dr. Brad Wenstrup, R-Ohio, spoke of his non-partisan volunteer service as a doctor of podiatry in Iraq; it is also known that he administered to a colleague shot on a ball field, and rushed to a train crash near Washington. After delivering some remarks with a scowl, Dr. Wenstrup was not about to ask questions of Dr. Hill. After she requested the chance to respond, Dr. Hill produced the little miracle of the hearings: As Dr. Hill spoke passionately about fairness and knowledge, the anger drained from Dr. Wenstrup’s face. He was listening – he had manners -- he maintained eye contact -- and he seemed touched, perhaps even shocked, that she was speaking to him as an intelligent adult. How often does that happen in politics? “He’s going to cry,” my wife said. As Dr. Hill finished, she thanked Dr. Wenstrup, and he nodded, and we saw the nicer person behind the partisan bluster. (I am including a video, but nothing I find on line captures the ongoing split-screen drama that we saw in real time. Maybe somebody can find a better link of this sweet moment, and let me know in the Comments section below.) I am thankful for Dr. Fiona Hill’s educated hopes for a wiser country. I am thankful to Dr. Wenstrup for listening. I wish them, and Ms. Yovanovich, and Lt. Col. Vindman and all the other witnesses a happy and civil Thanksgiving. (In other words: Don’t yell at your cousin for not agreeing with you!) * * * (In the video below, you might want to skip forward 5 minutes or so, to the point where Dr. Hill asks, "May I actually...." . The video, alas, does not show the split-screen version.) Johnny Cash and June Carter were making out on stage.

They were preparing for an awards show in Nashville, enduring the long waits that are part of any rehearsal. What better way to pass the time? This was in the mid-‘70s, and they were already an old married couple, but they seemed like teen-agers falling in love. My wife happened to catch the eye of Ann Murray, the great Canadian singer, who was sitting nearby in an empty row. They both raised their eyebrows – but affectionately -- as if to say, “Get a room.” I was thinking of this Sunday night during the latest episode of “Country Music,” the ongoing series from Ken Burns. The documentary may be a bit pat about racial and class divides and too formulaic about the terrible stresses of the ‘60s, but Burns has captured some of the personal statements of hope and change. Sunday’s two hours focused on the mid-‘60s, as a time of change, not only in country music but at lunch counters and marches in the South and campuses and towns all over America. Country music’s changes included Loretta Lynn’s song “The Pill,” banned for a while by some chicken radio stations, and Charlie Pride’s acceptance as a black star who sounded white. The series says that Loretta was the presenter for the top male award in country music, and was told to keep her distance if Pride were the winner. However, when they met on stage, she moved forward and gave him a hug and a kiss. Part Cherokee, Loretta was not going to let people tell her what to do in matters of race and color (or anything.) In her book, Loretta says it happened in 1972 when she won the Entertainer of the Year Award. “People warned me not to kiss Charley in case I won, because it would hurt my popularity with country fans. I heard that one girl singer got canceled out Down South after giving a little peck to a black friend on television. Well, Charley Pride is one of my favorite people in country music, and I got so mad that when I won I made sure I gave him a big old hug and a kiss right on camera. You know what? Nobody canceled on me. If they had, fine. I’d have gone home to my babies and canned some string beans and the heck with them all.” – “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” by Loretta Lynn, with George Vecsey. Other examples of ‘60s change were Dolly Parton, with her songs and her brains and her looks, willing herself up from East Tennessee poverty, and Merle Haggard, with his Warren Beatty looks and Bakersfield twang, overcoming his time in prison. The most compelling figure in Sunday’s episode was Johnny Cash, with his childhood of deprivation from money and love, discovering his talent, and his feel for injustice. In the’60s, while males in Nashville were wearing Nudie’s of Hollywood peacock outfits, Cash wore only black, to show support for the underdogs, but the color was also an expression of his moods. The series shows Cash blowing up his marriage for his passion for June Carter, but also getting deep into drugs. One live sequence shows him fidgeting at a recording session, twisting and turning, grimacing, removing his shoes, just out of his mind. In one live performance, Mother Maybelle Carter, singing backup, watches him warily, knowing that at any moment she and her daughters might have to scrape him up off the floor. That segment ought to be an advertisement for just about any human on legal alcohol or illegal ”recreational” or or the pain-killers doctors and big pharma push on people. Cash was zonked. Burns did not cite the song that Nick Lowe, Cash’s son-in-law at the time, wrote about Cash, who fine-tuned it into a standard: “The Beast in Me.” ….the beast in me That everybody knows They've seen him out dressed in my clothes Patently unclear If it's New York or New Year God help the beast in me… When I was working on Barbara Mandrell’s book, she told how as a precocious teen-ager she traveled with the Cash entourage, and was treated respectfully, but she also recalled Cash in a diner, nervously picking the stuffing out of a Naugahyde booth, just a bundle of nerves. The Sunday episode stressed personal revival, finishing in Folsom Prison, where Cash recorded his epic album, cracking jokes that the inmates got. He never had a better audience. There is a touching moment at the end where he performs a song written by one of the prisoners, and shakes his hand. I will vouch for the feeling Cash gave of a transformed – saved -- man, after he sought help for his addictions. In 1973, I interviewed him and June Carter in New York, upon the opening of a movie they had made about the life and death of Christ. He was calm, reflective, and they were deeply in love. Johnny Cash still wore black. Having met him a few times, I am sure he would be wearing it today. **** The back story to “The Beast in Me:” https://americansongwriter.com/2018/08/nick-lowe-the-beast-in-me/ *** My other memory of that rehearsal at the new theme park in the mid-‘70s, after the Opry had deserted its spiritual home, the Ryman Auditorium: Mooney Lynn (Loretta’s husband and my pal) and Roy Clark, the sweet-voiced troubadour, partaking of the upscale snacks, praising the hot and flaky hors d'oeuvre, which they lustily praised as “egg pie.” Quiche, that is. (They knew that. This is why I love country.) Even after King’s assassination and Angelou’s poetry and eight years of an idealistic, educated family in the White House, it never went away.

It festered under the rocks, all over America, and then, like some super-microbe, it reasserted itself in 2016 with the affirmation of essentially half a country. Now racism has its spokesman, its hero, speaking things that have been gathering in all corners of this diverse country, things people of color (my friends, my relatives) hear and feel every day: why don’t they go back where they came from? This sentiment generally refers to people of color, people who are “different,” people who speak out. The Other. Now they have their man, looking to weed out all those who don’t fit into the white mold. It’s been there all along. You can see it in the smug nods of the White Citizens Council that gathers behind the Grand Kleagle himself, Mitch McConnell, in the halls of the Senate. Now President Donald J. Trump has blurted it out, perhaps to the consternation of his backers, who prefer to do it by degrees, by gerrymandering, with the assent of the Supreme Court. Goodness gracious, even servile Lindsey Graham, lost without John McCain, has urged Trump to “aim higher” while essentially agreeing with Trump. Trump and his stubby little tweeting fingers let it fly on Sunday, the rant of a bigot who needs a minder, wishing that four women – of course, women, it seems to me that he hates women – of “different” backgrounds, urging them to go back where they came from. Except, of course, three of them were born in the United States, and all of them have succeeded admirably in this country which allegedly rewards strivers. But only if you’re Our Kind. There is no need to insert the quotes here, it’s all out there. The president wants to deport Latino immigrants without the right papers, but he also wants to deport, psychologically at least, people who are different, “troublemakers” (as the Chinese call dissidents), even elected representatives who are challenging their own Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi. Trump is speaking to his base, which seems to think the economy is going great -- for them, and that is all that matters. He is betting that the Supreme Court and the McConnells and the state legislatures will give his party – his race – an edge in 2020. And he is willing to play the race card, out in the open, knowing he has support, a lot of support. Speaking of deporting – go back where you came from – it is worth remembering that Trump’s grandfather, one Friedrich Trump, left Bavaria and wound up in Seattle, apparently running restaurants and hotels and maybe even brothels. When that earlier Trump went back to Bavaria and sought to resume his citizenship, they deported him because he had avoided military service – a perfect example of rampaging genetics, come to think of it. Friedrich Trump groveled to the prince: “Most Serene, Most Powerful Prince Regent! Most Gracious Regent and Lord!” And he concluded his plea: “Why should we be deported? This is very, very hard for a family. What will our fellow citizens think if honest subjects are faced with such a decree — not to mention the great material losses it would incur. I would like to become a Bavarian citizen again.” In Bavaria, they told Friedrich Trump: go back where you came from, so he wound up in Queens, New York, and his son, Fred Trump, was soon keeping black people out of his apartment buildings, on his way to shielding his revenue from taxes, to pass on to his children (one of them a judge; only in America.) Now the grandson tells four duly elected members of Congress to go back where they came from, his rant based on racism. He has touched off a storm, but Trump has an audience. It never went away. * * * (The reaction to Trump’s racist bleat on Sunday) https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/14/us/politics/trump-twitter-squad-congress.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage (The deportation of Friedrich Trump) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/donald-trump-grandfather-germany-letter-deportation-us-bavaria-dreamers-a7903071.html https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2019-07-15/the-latest-trump-renews-attacks-on-4-congresswomen (Even Lindsey Graham urges Trump to aim higher) https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2019-07-15/the-latest-trump-renews-attacks-on-4-congresswomen I was poking around my iPod, listening to downloaded pop songs beginning with “M” – “Manha de Carnival” with Susannah McCorkle, “Manhata” with Caetano Veloso, The Dead’s version of Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried’– and up popped “The Man in Black,” by Johnny Cash.

I was immediately nostalgic for the man, and the mood, his all-black outfits, and the coal-black eyes piercing the soul of the audience. Where are you, man? This became his signature song, performed for the first time at a concert at Vanderbilt University in 1971 – a time of anti-war and pro-civil rights fervor. He addressed some students in the audience, saying that a conversation, few days earlier, had prompted him to write this song, explaining why he wore only black out in public. I want to add that I met Johnny Cash a few times – once backstage at the Opry in the old and beloved Ryman Auditorium, just a bunch of people hanging around, a few feet away from the live performance. He was just one of the people backstage – old Ernest Tubb, young Dolly Parton, vibrant Skeeter Davis, people just hanging and chatting. When he produced a Jesus movie in the mid ‘70s, I interviewed him and June Carter at C.W., Post College where the movie was being showcased. Again, he was the most approachable and democratic star, talking about his faith as a baby Christian, but (a gigantic “but”), not patronizing or dogmatic. They were the nicest couple. My wife and I saw them again at a rehearsal for the country awards at the new (and sterile) Opryland in the early 80s. He and June were smooching during a break in the rehearsals; Anne Murray, sitting nearby, locked eyes with my wife, and they smiled warmly, as if to say, “Get a room.” Johnny Cash and June Carter were in love. Not long afterward, catching a red-eye in California, I saw him coming down an empty corridor, a big man in black, his eyes a zillion miles away. I most definitely did not say hello. Anyway, I think I can say, having been around Johnny Cash a few times, and having listened to his work (his time-growing-short album, “American Songs”), that he had a feel for his country, the poor, the imprisoned, the people trying to get clean, the marginal and the diverse. I think I can say he hated bullies and pretenders. He came from rural Arkansas and he knew cities and campuses, could talk with students at Vanderbilt, could take their questions and make a song out of them. I wish he were writing songs today, in the time of The Man in Orange. * * * (Just in case you are not into Johnny Cash’s voice, here are his lyrics.) Man In Black Johnny Cash Well, you wonder why I always dress in black, Why you never see bright colors on my back, And why does my appearance seem to have a somber tone. Well, there's a reason for the things that I have on. I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down, Livin' in the hopeless, hungry side of town, I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime, But is there because he's a victim of the times. I wear the black for those who never read, Or listened to the words that Jesus said, About the road to happiness through love and charity, Why, you'd think He's talking straight to you and me. Well, we're doin' mighty fine, I do suppose, In our streak of lightnin' cars and fancy clothes, But just so we're reminded of the ones who are held back, Up front there ought 'a be a Man In Black. I wear it for the sick and lonely old, For the reckless ones whose bad trip left them cold, I wear the black in mournin' for the lives that could have been, Each week we lose a hundred fine young men. And, I wear it for the thousands who have died, Believen' that the Lord was on their side, I wear it for another hundred thousand who have died, Believen' that we all were on their side. Well, there's things that never will be right I know, And things need changin' everywhere you go, But 'til we start to make a move to make a few things right, You'll never see me wear a suit of white. Ah, I'd love to wear a rainbow every day, And tell the world that everything's OK, But I'll try to carry off a little darkness on my back, 'Till things are brighter, I'm the Man In Black Songwriters: Johnny Cash Man In Black lyrics © BMG Rights Management  Western PA: Halfway between NY and IL, couple crossed Roberto Clemente Bridge to catch a ball game. Western PA: Halfway between NY and IL, couple crossed Roberto Clemente Bridge to catch a ball game. After months of home-repair madness, it was a treat to spend a quiet Easter at home. Then the pinging began on the phone. I was puttering around, trying to restore order from the detritus of repairs. Marianne made a delicious vegetable-and-chicken soup.  New England: Easter Egg Atelier checks in WNYC-FM was playing weekly jazz show. Two versions of "April in Paris," first by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, then by Count Basie ("one more -- once") Homage to the stricken Cathedral de Notre-Dame. Mel Torme. Bob Dylan. An American blues singer acing a song. Not American, my wife said. It's Adele. As always, she was right. When friends in Jerusalem and the Upper West Side send the same link, it makes sense to read it -- and pass it on. Roger Angell, 98, has some thoughts on election day and citizenship.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/get-up-and-go What could be more American than an essay on voting by a hallowed member of the writers' wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame? Enjoy....and vote. http://www.joedarrow.com/sports-figures/ (The art was a bonus. I found it on line, and consider my posting it here as an endorsement for any artist who can put these three dudes in the same work.) We stopped for gas on Interstate 80 in Pennsylvania and spotted a food truck.

Or rather, we spotted the sign. I was instantly sorry we had just eaten a great lunch and dessert after I gave a talk for adults and met with students at the bustling journalism center at vibrant Susquehanna University, in the pleasant river town of Selinsgrove, Pa. After lunch in such good company, no way we could even sample a tamale. But I pointed at the sign alongside Zapata’s Food Truck at Exit 256 and told the guys outside: "Próxima vez." Next time.  Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) It is Black History Month, which means I always learn something. This Black History Month has caused me to re-think my position on the first woman, or women, who should be on an American bill. But first: Three years ago, Terrance McKnight of WQXR-FM did a documentary on a composer I had never heard of, Florence B. Price. The other night, PBS ran a visual documentary on Price, and by now her music was more familiar to me, ranging from traditional classical to black gospel. One of the experts (mostly black, via Arkansas Public Television) compared her to one of my favorites, Antonin Dvorak, who used folk music (in the deepest sense of the phrase) of two worlds, Bohemia and America. Artists generally have it hard, but black artists have it harder. The PBS documentary showed how Price was inspired by classical music but segregation and economics held her back. She always had to be double good. (Sound familiar?) In one pathetic episode, already accomplished, Price wrote a letter to Serge Koussevitzky, the legendary director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, asking to compose for him, and she felt the need to call attention to being “Colored.” He never wrote back. Yet she had her triumphs. Mainstream conductors and critics and performers took her seriously, notably in her adopted home town of Chicago. In one of the great moments in American history, Marian Anderson performed at the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial, April 9, 1939, after Eleanor Roosevelt had forced the issue. Anderson sang a hymn by Florence B. Price, her friend. In the Arkansas documentary, an elderly black woman recalls, half a century later, being young and seeing a black woman singing to 75,000 people. The old lady daubs her eyes with a handkerchief. I bet you will, too. How hard it was, how hard it is, to be black in America. Just look at the dignity of people who have been poisoned in Flint, Mich., because of the incompetent and heartless regime of a latter-day plantation massa, Gov. Rick Snyder. But there are triumphs. Look at the lovely front-page photo of President Obama, speaking at a mosque in Baltimore, calling for a cessation of prejudice, as children smile in awe. We have seen those smiles on black service members when Obama visits the troops and on black citizens when Obama goes out in public. So there is that. But Black History Month reminds us how hard America has been on any black who aspired. That is why I am wavering in my position that Eleanor Roosevelt should be on a bill. I think she may be the greatest woman yet produced by the U.S.A., but her greatness may have been in her advocacy of the underprivileged, for people of all colors. Now I think the next bill (lose Andrew Jackson off the 20, not Alexander Hamilton off the 10) should be a tribute to the great women of color in America. Who? How many? I leave that to historians. But when that glorious bill arrives, somebody should play the classical music of Florence B. Price. Below: The multitalented Terrance McKnight accompanies Erin Flannery in “To My Little Son,” by Florence B. Price: We’ve managed to catch some of the wonderful Ken Burns documentary on the Roosevelts on Public Television – a great vision of America, as vital as today’s front page.

In the parts we’ve seen, I recalled my slight personal connections to Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt. As a young reporter, I interviewed Theodore Roosevelt’s younger daughter, Ethel Carow Roosevelt Derby, by then in her eighties, in Oyster Bay, Long Island. I almost blew the interview right away by referring to her father as a hunter. He was not a hunter, she snapped; he was a sportsman. (I had seen those heads in the museum.) The documentary refers to him often as a hunter. Mrs. Derby would not be amused. As a five-year-old, in a household that loved Franklin and Eleanor, I was taken to his campaign through New York on a miserable rainy day, Oct. 21, 1944. I recall being on a hillside, watching the motorcade on Grand Central Parkway. The car was open, and his face was pasty white. The web says he told the crowd in Ebbets Field that he had never been there before, but claimed he had grown up a Brooklyn Dodger fan. He died six months later. That romp through the boroughs did not help. Eleanor Roosevelt was a staple in the politics and affection of my family. Later we read books about how she pressured her distant husband into absorbing information about the plight of so many Americans. Two things I have heard about Eleanor Roosevelt lately: When I was working on the Stan Musial biography, I learned that Musial had joined a tour for John F. Kennedy in 1960, which included Angie Dickinson. The actress became a knowledgeable source about that campaign, telling me how she was addressing a crowd in the New York Coliseum on the Saturday before the election: “My big claim to fame is that I was making my speech, and I heard a hush and they wheeled in Mrs. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, and I got to say, ‘What I have to say isn’t important’– I almost was finished – ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the great Eleanor Roosevelt,’ and I got to introduce her.” Dickinson’s respect, half a century later, was palpable. I learned something about Mrs. Roosevelt recently while reading a very nice history book – Indomitable Will: Turning Defeat into Victory from Pearl Harbor to Midway, by Charles Kupfer, an associate professor at Penn State Harrisburg. In the first shocking hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the President assembled advisors and friends in the White House, including Edward R. Murrow, the CBS broadcaster (this was back when networks maintained serious news organizations.) FDR picked the brains of Murrow, who had access to the back rooms of the White House. Eleanor Roosevelt, who had fought for millions of poor people, who had fought for civil rights and women’s rights, cooked some eggs for Murrow. Kupfer’s book had me, right there, on Page 22. The Burns documentary had me as soon as I saw the insecure half-smile of young Eleanor Roosevelt, before she discovered the activist within. Her wise eyes take the measure of a country that has failed its people. She spends her own money to build experimental communities in deepest West Virginia. She sets an example. The camera cannot find too much of her. She reminds us of the men who went to war, the women who went to work, the blacks who wrote letters to the President, asking for help. Her face reflects the country many of us thought we were, or could have become. As I wrote this, I flashed on something else about the Burns documentary: Elizabeth Warren reminds me of Eleanor Roosevelt. The pose looked familiar – Americans unloading water from an aircraft carrier to the stricken islands of the Philippines.

It brought me back to the United States of my early childhood, toward the end of World War Two: not so much the fighting, but the recovery. When I was five, this was one face of America – G.I. Joe passing out chewing gum to the children of Normandy. Later we saw photos of Americans liberating concentration camps. Perhaps it was a simplistic image, maybe even manipulated, but it was what we thought of the country, of ourselves. The Marshall Plan, the GI Bill, the post-war hopefulness, only reinforced that image. We took care of others; we took care of our own. The news that the United States was dispatching the carrier George Washington to the east coast of the Philippines struck a familiar chord. Better than chewing gum – tons of water and medical supplies, delivered by helicopter to Leyte and Samar. It reminded me that when the nihilists struck on 9/11, I got emails from friends in Japan and Mexico and France, asking, “Are you all right?” We were all in it together. I am reminded of that when I hear an American president remind us what soldiers know. You take care of your own. The current president comes from that American heritage when he talks about the need for a more national health care. Even with the technical glitches – SNAFU, they called it during the war – the goal is to keep all of us away from the emergency room, to address hunger and illness in the early stages, while there is still time. The American president reminds me of G.I. Joe. The people who sabotage him do not. I have just squandered an hour or two of my life trying to solve the maze of streets named Peachtree in the northern Atlanta suburbs. At $4 a gallon, this isn't funny. My two sisters live in the northern burbs – half an hour apart, a long way from Queens. Between them are a staggering number of streets named Peachtree – Peachtree Corners, Peachtree Parkway, Peachtree Industrial Boulevard. In the dark, on badly-engineered roads with wretched signage, this can be downright frightening. I have seen estimates that over 70 streets in the Atlanta area have the word Peachtree in them. This suggests a staggering failure of imagination, if all the planners of the New South cannot do better than slap the name Peachtree on bisecting boulevards. But I have a proposal. And it involves the great American pastime. The Atlanta Braves have been in town since 1966, and by now have accumulated enough history to provide heroic names to replace most of those Peachtrees. What makes it worse is that I just read that the name peachtree just may have stemmed from the type of pine, called a pitch tree, common to the south. How fitting if this regional jumble were based on a mistake. I learned to like Atlanta during the 1996 Olympics (we lived in the very sweet Inman Park neighborhood near downtown) and later when my son’s family lived in Inman Park and moved out to Roswell. March is a gorgeous time to visit Atlanta. So is October. This past weekend was a flying visit for a family reunion, but whenever I have time in Atlanta I love to visit friends and old haunts. However, I have a Peachtree rule: If a restaurant or some other business is listed on something called Peachtree, I won’t even try to patronize it. Otherwise, I could be driving up and down the region from Buckhead to Norcross, looking for the right Peachtree. Here’s my proposal: Keep one Peachtree St. The main drag on the spine of the hill in downtown Atlanta would seem to be the logical choice. Then they should name every other Peachtree after a Braves stalwart – and there have been dozens of them. Henry Aaron? Phil Niekro? Dale Murphy? Greg Maddux? Chipper Jones? Bobby Cox. I could keep going. John Smoltz. Tom Glavine. Rico Carty. And when they are finished with the stars, I bet there is some humble little Peachtree Circle out in the middle of nowhere, where confused out-of-town drivers sometimes blunder. One modest cul de sac could be named Francisco Cabrera Circle, in honor of the vagabond who delivered the clutch hit that put the Braves into the 1992 World Series. Who should be in charge of this crucial task to end the anarchy on the Atlanta highways? This task demands an eminent historian. I suggest the Georgia favorite who is currently blustering around the country, running for public office. Pretty soon, Newt Gingrich is going to need a job other than soliciting funds from wealthy sponsors. It’s time to put Newt’s massive intellect to work on something truly challenging -- ending Peachtree anarchy. |

Categories

All

|