|

For decades, they were teammates in the sports pages of that great paper, Newsday.

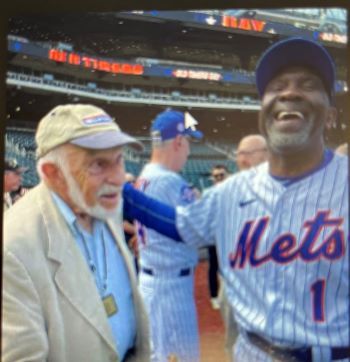

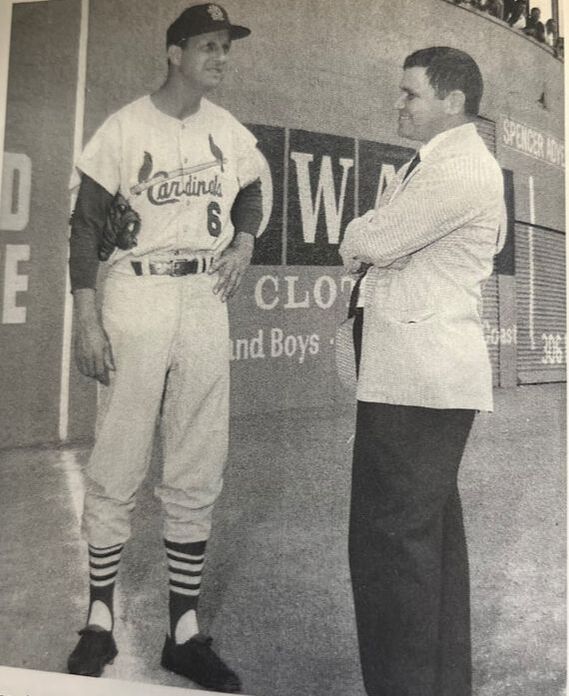

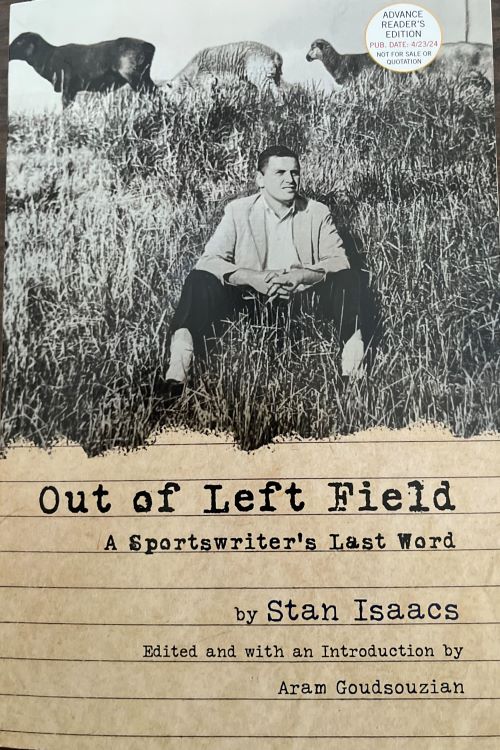

Steve Jacobson could cover anything, and ask probing questions, Stan Isaacs saw life from his natural position – way out, left field. They were my colleagues and my friends and my inspiration when I worked at Newsday in the 60s. We even played touch football together. Stan passed in 2013 but his words are being revived in an autobiography, “Out of Left Field: A Sportswriter’s Last Word,” to be published in April by the University of Illinois Press. Steve is very much with us in a current podcast celebrating a magnificent book he wrote in 2007: ”Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball – and America,” by Lawrence Hill Books. Steve’s book is, alas, out of print at the present time (as Casey Stengel used to say), but just in time for Black History Month, Jacobson -- known as Jake -- has been celebrated in a podcast by Steve Taddei, from his perch in the Bay Area. “I found ‘Carrying Jackie's Torch’ at the public library,” Taddei wrote in an e-mail. “The book fit in well with ‘Leadership Lessons From the Negro Leagues,’ because it gave me perspective to the adversity my heroes of the 1960's and 70's went through and overcame on their journey to the Major Leagues.” It is no secret that the evils of segregation, which kept Black players out of “organized” ball were not magically dispersed by Jackie Robinson’s first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Robinson took the first curses from opposing dugouts, the blatant reluctance of some Brooklyn teammates, and the daily problems of living in a considerably racist nation. And it was still going on when Steve Jacobson was interviewing players in the 60s. One of the most approachable was Jim (Mudcat) Grant, a star pitcher, who one day challenged Steve to expand his questions: talk to other Black players who ran into the walls of segregation. Years later, that’s what Jake did – hearing how Black players at first could not stay in hotels with their white teammates, how they had to eat brown-bag lunches in team buses, how Black players felt underrated by their managers and teammates. Always a dogged reporter, Jake sought out players we knew from our working years --Tommy Davis who always greeted writers from “my hometown” of Brooklyn, Ed Charles, the spiritual center of the 1969 championship Mets, Bob Gibson, the great pitcher who used his hard veneer to keep hitters – and reporters -- at bay, and Dusty Baker, whose winning personality has carried him to an enduring career as manager. Henry Aaron. Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby. In this podcast, Steve Taddei spoke by phone with Jake (and me, a little) and near the end, Anita Jacobson, Jake's wife, tells about the hotel pool in Florida, where the Mets took spring training, circa 1965. The formidable Anita -- who cooks, and teaches cooking-- recalls what she and my wife Marianne did when another white mother pulled her child out of the pool rather than share chlorine water with a Black child. Life was like that for the Black baseball people who carried Jackie’s torch. Steve Jacobson worked hard to get memories of the Black players, and now Taddei has honored what Jacobson did in his book. Here’s the podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/leadership-lessons-from-the-negro-leagues/id1646816110?i=1000644226588 *** And here is the glorious scoop of the day: Stan Isaacs’ words are back in print. In his retirement, Stan was writing his memoirs, but after the crushing death of his vibrant wife, Bobbie, in January of 2012, Stan’s heart was broken, and the book was unfinished when he slipped away 15 months later. Fortunately, Aram Goudsouzian, an editor for the University of Illinois Press, became interested in the genre of sportswriters – starting in the late 50s, in their chattery, irreverent, fearless and informed glory in the 1960’s. The Chipmunks: Stan Isaacs. Larry Merchant of the Philadelphia Daily News and Leonard Shecter of the New York Post and a dozen or more chatterers. “I’ve been working on a book about sportswriters and the big political and cultural shifts of the 1960s, and in the course of my research I read Mitchell Nathanson’s excellent biography, Bouton,” Goudsouzian wrote in an e-mail. “In the notes he had a record of Stan’s unpublished memoir, which I thought might be a good primary source for my own book. So I emailed Nathanson about it, and he put me in touch with Stan’s daughter Ellen, who sent me an electronic copy. As I read it, I had the sense that it should be published – though it needed editing, it had Stan’s distinctive voice and a lens into the shifts of the Chipmunks’ era.” Never having met Stan, Goudsouzian gave the manuscript some nips and tucks, and undoubtedly some enlightened surgery to highlight the inner Isaacs. Stan knew himself as a quirky lefty, coming out of the Depression and the politics of the 1930s, and he tells his best stories in this book. The photo on the cover? One night, covering the Yankees in the old ballpark in Kansas City, Stan chose to watch the game from the hill behind right field, patrolled by a few sheep. Vintage, definitive Stan Isaacs. They were wonderful days -- and I carried them with me to the Times in 1968, blessed with the skills and attitude of Isaacs and Jacobson and the other Chipmunks. I am extremely proud of my career at The Times, but like ball players who have loyalty to more than one ball club, I still refer to both Newsday and the Times as "we." Jacobson’s world, Isaacs’ world, are definitely from another time. Nowadays, young people do not read newspapers…and newspapers die….and even a great paper like The New York Times has chosen to blow up its sports section, with its tradition of reporters and columnists licensed to report and comment. Miraculously, in these hard times for sports sections, Stan Isaacs still patrols left field and Steve Jacobson still carries Jackie’s torch. Together again. In the midnight hour on a murky Saturday night in late October of 1986, Shea Stadium was going mad.

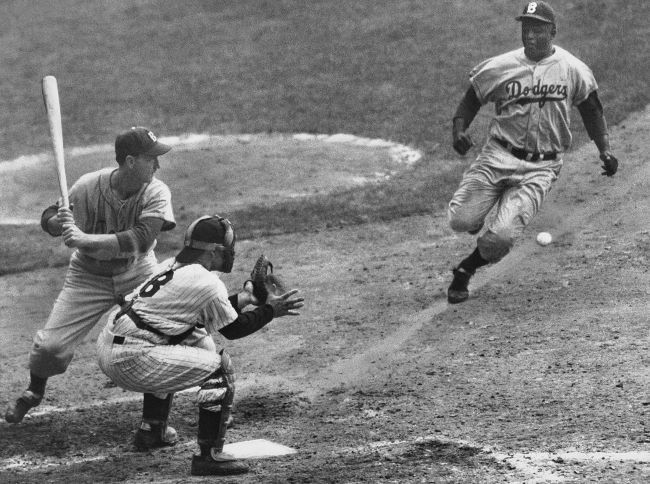

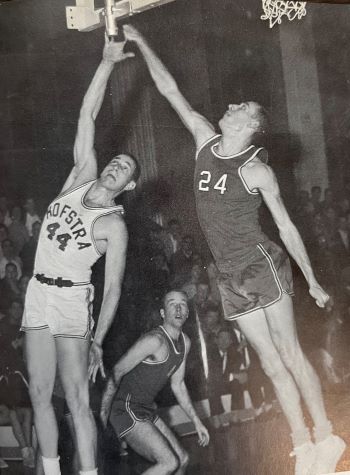

A squiggly grounder by Mookie Wilson had somehow kept the Red Sox from winning the World Series that night – and fans were screaming, and nearly a dozen New York Times writers were pounding away at their laptops, shouting into phones, bustling noisily to update their early stories for the last print deadline of the evening. Enlightened cacophony. The sports editor, Joseph J. Vecchione, sitting behind us in the pressbox, was coordinating with the staff in the office, making dozens of decisions, on the spot. Then it was over. We had gotten it done, on deadline. A young Times news reporter, doing spot duty to cover fan madness, police activity, etc., watched the sportswriters (so often maligned as “the toy department”) do their jobs. When things quieted down, the young reporter said casually to the sports editor, “Wow, that was impressive,” or words to that effect. And Joe Vecchione said drily: “We do it every day.” If Joe had added, “Kid,” he would have sounded just like Clint Eastwood in “The Unforgiven.” That professional pride epitomized Joe Vecchione, my friend and advisor in my early days of writing the sports column. Joe passed Friday evening at 85, after years of suffering from Lewy body disease, cared for by his wife, Elizabeth, a wise and devoted nurse. They are parents of Elissa Vecchione Scott and Andrea Vecchione, with three grandchildren: Joe’s aura of family man was clear to people around him. He was a boss with values. I got to know him as a terse, decisive voice on the phone, in the 70’s, when he was an editor in the photo department, and I was a news reporter. Sometimes I was at breaking news and I had to coordinate with the photo editors. Joe was authoritative and efficient. Then he was plucked by Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Gelb to help form the new SportsMonday section, and he was there in 1980 when sports editor LeAnne Schreiber recruited me to be a reporter, filling in for Red Smith or Dave Anderson here and there. When LeAnne moved on, Joe became sports editor, and when Smith died in 1982, it was Abe Rosenthal’s decision to hire a new columnist, and it turned out to be me. Here is where the kindness and shrewdness of Joe Vecchione took over. I had been conditioned by 10 years as a Times news reporter, to keep any trace of myself out of the copy. Give sources. Quote authorities. No opinions. That was the old, gray NYT – and I was one of the foot soldiers, thoroughly indoctrinated. As a columnist, I knew the subject matter, and could write and report, but I was trying too hard to find a voice, hinting at my opinions. I was being too cute. Joe had some advice (and I paraphrase:) “Be yourself. Tell us what you think. People want to know how you feel, what you know, what is right and wrong. Don’t hold back. This is the way things are going these days. You have freedom.” He removed a decade of thoroughly valid reportorial rules, freeing me up to be a columnist. Joe also had an instinct for hiring and enabling good people, hiring columnists Ira Berkow and Bill Rhoden, relying on deputy editors like Bill Brink and Lawrie Mifflin, and he backed up his columnists. I benefited from this in 1990, when I was writing columns from the World Cup of soccer, held in Italy. The young American team, in its first appearance in 40 years, managed a taut 1-0 loss to the Italian team – a huge accomplishment. But I pointed out that Italy did not have great strikers – that is, players gaited to score goals from up close – and I wrote this was because their great national league imported scorers from Germany and Argentina and Brazil. I wrote: “The home-grown players do not develop the knack of scoring. Mussolini once lamented that his was a nation of waiters. It is not stretching the truth to say that Italy is currently a nation of midfielders.” The next day, the sports department got a call from an Italian-American reader who felt using the remark attributed to Mussolini was prejudicial. (Fact is, I love Italy and root for the Azzurri, except when they play the U.S.) The person in the office, taking the call, told the reader that the sports editor was okay with my comment. And who is the sports editor? “Joseph J. Vecchione.” That pretty much ended the conversation. Joe could be tough, and he had to make a lot of decisions. I once was whining in the office about something or other, and Lawrie Mifflin, the deputy sports editor and loyal friend of Joe’s and mine, told me, in effect, “You have no idea how much he has to handle every day” – including complaints from leagues, teams, player unions, sponsors, agents, public officials, fans, to say nothing of staff members. In Joe’s regime, we let it fly, and Joe fielded the complaints, kept most of it from our ears. Joe was sports editor for a decade, then moved back into the mainstream of the paper. He retired at 65 and the editors promptly brought him back to help the transition to the new building a few blocks away. Over the years, I was impressed by the masthead names, the serious people (some of whom condescended to sports personnel), who were his social friends. They trusted him – for core values, like honesty, like thoughtfulness, like culture. That is no small statement about a Times official, my friend, who helped move the sports department into the future. (Any insights/anecdotes about Joe? Please add them in Comments, below.)  Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, Jamaica ’56 and Hofstra ’60, passed on June 10. He had turned 83 on June 1, and had been in failing health for months, lovingly cared for by his wife, Roberta. This is a hard one for me to put together because Stan and I were in the same school for nine straight years -- Halsey Junior High and Jamaica High in Queens, then Hofstra College in Hempstead. Then Stan went to dental school and served as a dentist as a captain in the Army at Fort Lewis, Wash., and settled into his practice in New Hyde Park, marrying Roberta Atkins, helping her with their two children, driving around to dog shows all over the place, in with their English Mastiffs -- a big guy showcasing his big pets. We became much closer in the past two decades, as old Hofstra basketball and baseball guys (and one aging student publicist) got together at Foley’s in NYC. I would drive into the city and back, sometimes with other front-liners, Donald Laux and Ted Jackson. Basketball was our common denominator. Stan had a great souvenir of his season as a 16-year-old senior on the Jamaica varsity -- a scar on his forehead, from the city tournament in the old Madison Square Garden when he was hammered by Tommy Davis of Boys High. When Tommy became a star with the LA Dodgers, I would remind him that an endodontist on Long Island was looking to get him back.  Stanley in 59-60 season. Stanley in 59-60 season. I was at courtside on a sleepy January afternoon in 1960 when Hofstra lost on a long basket by Wagner at the buzzer. It turned out to be the only loss in a wonderful season – 23-and-1, but not good enough to get into a post-season tournament. Half a century later, we caught up with the villain who had beaten Hofstra with that long jump shot – Bob Larsen and a couple of teammates met a few old Hofstra guys at Foley’s, and I wrote about that in the Times., https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/sports/ncaabasketball/52-years-later-recalling-a-shot-that-sank-a-season.html In our old age, basketball was the link. Stanley had two season tickets at the Hofstra gym, right above the scorer’s table, and sometimes he would invite me. He became friendly with the coaches, first with Mo Cassara, then with Joe Mihalich, two basketball lifers who loved our old stories about the memorable coach, Butch van Breda Kolff, the old Knick. (Crude and also insightful, Butch was oddly formal, often calling his players by their full first names—Donald, Curtis, Stanley. As the publicist, I was “Grantland.”) Every October, Joe would invite us to a practice, let us sit behind the basket, give us frank insider critiques of his team. He called Stanley “Doc.” For one afternoon, my guys were part of the team, part of the school, again. I remember at one October practice, the star of the team, a shooting guard at 6-foot-3, also from Queens, was chatting with us, and was politely bemused that Stanley was the star rebounder at the same height. (I wrote about those sweet annual visits to our alma mater.) https://nationalsportsmedia.org/news/my-alma-mater-thrills-some-old-players- Just before the pandemic, Stan stopped getting around, because of Parkinson’s disease and other problems. We would talk on the phone and he would talk about Roberta’s art work and how well she took care of him…and proudly about their family: son, Harry, who had taken over the endodontist practice, (“better hands than me”) and his wife Macha and their children, Max and Remy, and Stan and Roberta's daughter, Margaret Morse, and her husband Richard and their children, Olivia and Henry. He always knew what they were doing. When I visited them last week, Roberta was masterfully managing a hospice operation. (I never heard him complain about his bad breaks with health, and he was always upbeat about the home care from aides like Kenia.) We sat by his hospital bed and we talked about the old days and our dwindling Hofstra guys, and his Yankees and his Rangers….and I praised how inclusive he was about his basketball world. This is what I told him: A decade ago, my wife and I were visiting our friends, Maury Mandel and Ina Selden up in the Berkshires, and Maury’s kid brother Joe and his wife Jean were also there. I suddenly blurted to the younger brother, ”Hey, I know you – from junior high school.” Turned out, Joe had been in the same class as Stanley – and had played on the same class team (Stanley was also on the school team.) I ostentatiously pulled out my cellphone and called Stanley: “I got Joe Mandel here, from Halsey.” They started chatting, more than six decades later, and Stanley told him, “You were a good point guard on our class team.” As any old schoolyard player knows, there is no higher compliment than being praised by a college star. Generous guy, Stanley. Then they started talking about the girls in their class. We continued that conversation the other day -- basketball and girls in our grade -- and for a few minutes, it was very nice to be 13 again. ** (It's so nice to see comments or emails to me, from old friends. Ken Iscol from junior high. Jean White Grenning and Wally Schwartz from Jamaica. A lot of the Foley's gang. Just to drop a few names. Roberta (I knew her brother, Jerry Atkins -- in grade school!) has held things together, admirably. The funeral is Monday at 11:30 AM at Beth David Cemetery, 300 Elmont Rd., Elmont, N.Y. 11003.) For the moment, please feel free to remember Stanley…and say hello to Roberta and the family… here…. They are monitoring the lovely comments here on this site. Thanks. GV Omigosh, Mike was there! That was my reaction while electronically poking around online files and saw this angle of Jackie Robinson sliding toward Yogi Berra in the 1955 World Series. The umpire ruled Robinson had stolen home, but to the end of his days, Yogi would levitate loudly, to dispute that call. But I’m not writing about baseball today. I’m writing about photographers like my late friend Meyer (Mike) Liebowitz, who passed in 1976 but lives forever in the stock of photos, now being included in a digitizing project by the Times. (That project was described in a two-page spread in Sunday's Metropolitan section. See link below.) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/books/reading-around-new-york.html In the dozens of times Mike and I worked together on news – not sports – stories on Long Island, he never once mentioned that he was one of the photographers arrayed around Yankee Stadium that epic day. (John Rooney of the AP caught the slide/tag that, to this day, proves nothing.) Mike Liebowitz one of dozen photographers I got to know – and admire – on our assignments together. This digital project reminds me that one of the under-described relationships in journalism is somebody with a pad and somebody with a camera, going on assignment, watching each other’s back. I was in my mid-30s and Mike was surely twice my age when we were paired by the random needs of the Photo Desk, Sometimes I would be in his car because it held his equipment. Once we were chasing a politician allegedly visiting an estate in Nassau County’s gold coast. Down a long driveway, we knocked on a door and were told to take a hike, so Mike backed out the driveway – and we nearly got T-boned by a speeding car. Another time we were doing something way out on the North Fork (a project to save the fading potato farms?) on a glorious early October day, and Mike was driving along an untended beach and the tide was high, so I asked Mike if he had 20 minutes to spare, which he did, so I stripped down to my skivvies and dove into the warm, placid waters, and then we proceeded due west. In that two-page spread in the Times’ Sunday metropolitan section, there are 12 vintage photos about reading in public. What touched me was that I worked with just about all the photographers – Jim Wilson, Keith Meyers, Marilyn K. Yee, Fred R. Conrad, Andrea Mohin, Chester Higgins, Jr., and William E. Sauro, who did a lot of sports. And that doesn’t include other Times pioneers like Michelle Agins (who one Christmas Eve popped over to my family dinner and took a treasured photo of four generations) and Sarah Krulwich, who has become an institution with her photos of everything Broadway. Or dapper little Ernest Sisto, who worked on the field back in the day of bulky Graflex cameras, and would get a discreet signal from his compagno Phil Rizzuto when the Scooter was about to drop a bunt. And then there are my two pals from the 1994 Winter Olympics in Norway – Paul Burnett, who took photos of the presumed winner, Nancy Kerrigan, and Barton Silverman, who was snapping Oksana Baiul, who went later. Barton was – and I am sure still is – a force of nature. He got roughed up covering the 1968 Democrat convention in Chicago, and in 1996 he was nearly arrested in Atlanta for trespassing in the new Olympic park in downtown Atlanta. (I tried to warn him.)

I know I am omitting a dozen or two Times photographers, but I want to discuss another facet – free-lance photographers. I don’t know what it is like now, but when I was a news reporter based in Louisville, the Times used great photographers from the Courier-Journal in their spare time (my late friend Ford Reid, for one), and also a free-lancer named Kenneth Murray, a true son of Appalachia from the Tri-Cities area where Virginia and Tennessee meet.

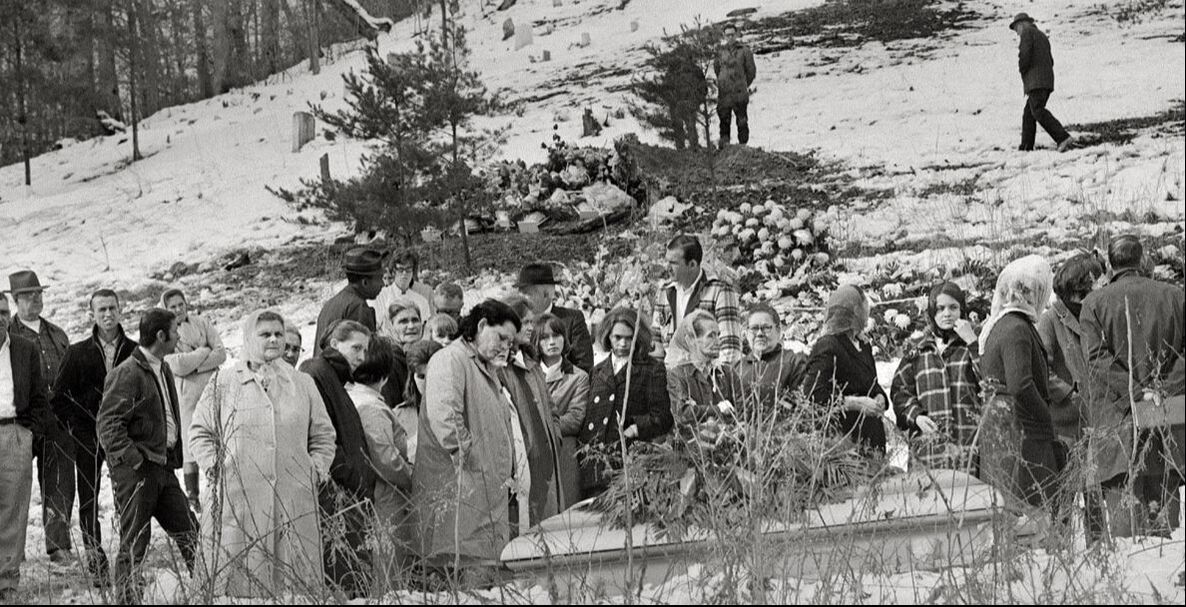

I met Ken at the first funeral after the terrible Hyden coal-mine disaster in Eastern Kentucky, Dec. 30, 1970, and he kept going to funerals for most of the 38 miners. Later he began working with me all over Appalachia. In March of 1972, we got together when a coal-mine’s lethal lake of waste water broke loose and drowned 125 people along Buffalo Creek, W. Va, one rainy Saturday morning, with no warning from the coal company. Ken and I decided to look around for more of these “slurry ponds” and got caught in some deep woods, by a few guards flashing pistols. As we tried to explain it was all a big mistake, Ken whispered to keep edging our way down to the state road, to public land, which we did, safely. Some of my best times were spent out on the road somewhere, with Tom Hardin of Kentucky, Don Hogan Charles of the NYT, Gary Settle of the NYT and Seattle, Chang Lee of the NYT, John McDermott my soccer buddy from San Francisco and now Italy….and more. And the news about the digital project makes me happy that the Times will preserve the work of its own artist-journalists, in its way, a hall of fame for these people who became legends to me. Henry Aaron. Tommy Lasorda. Jim (Mudcat) Grant. Poring over the magnificent two-page spread in the Times, honoring prominent people who passed in 2021, I realized I could write reams about stars I knew from the locker rooms. I could also recall famous people I met here and there – Colin Powell, streetwise New Yorker ---- Vartan Gregorian, kind Armenian wise man -- and Larry Flynt, seedy champion of pornography, who happened to be a hilarious and incisive interview. But my heart, at year’s end, is remembering relatives and friends I got to know up close, who have left a personal gap. As Arthur Miller wrote: Attention must be paid. Aunt Lila. She was my wife’s aunt – helped raise her -- but she also became my aunt, jolly and chubby with a beautiful smile and a generous hug, over the decades, sidling up to me and asking about our children, our work (she had an admirable curiosity), and whether I knew the Lord. Her children and grandchildren cared for her in old age, shuttling her from northeast Connecticut to suburban Long Island, keeping her going, medically and socially. At a reunion last summer at a daughter’s home, Aunt Lila was wan, low on energy, and Marianne sat by her all afternoon, sensing this might be the last time, which it turned out to be. But Aunt Lila’s smiles and hugs and kind acceptance linger on. Captain Curt. Once a point guard on very good basketball teams at Hofstra, Curt Block became a publicist at NBC and had other memorable gigs. (As a young reporter, he interviewed young Cassius Clay, and had the presence of mind to keep the rudimentary tape, re-discovering it in old age.) When aging baseball and basketball players (and one scribe, me) began to meet periodically at Shaun Clancy’s great place, Foley’s, Curt took the slow train up from Philadelphia and became the greeter, the treasurer, the captain, sitting in the middle, enjoying everybody else’s stories, moving the ball around, as he had against Hofstra’s opponents, back in the day. He quietly alluded to impending heart surgery, and last summer he went to sleep and did not get up. Because of the pandemic, the old boys have not been able to meet since, to uniformly mourn our quiet leader. Neighbor and Nurse. Ann Schroeder was a nurse in the Bath-Brunswick area of Maine. She got to know my wife’s Uncle Harold (older brother of Aunt Lila) and she became a volunteer guide to his old-age miseries. We got to know her through her detailed emails, explaining Harold’s health problems, what was being done, so we could assure his relatives that he was surrounded by skilled, loving friends in that wonderful area that has become our own sentimental home. After Harold passed, we stayed in touch – via health newsletters Ann sent. She casually alluded to her own breathing issues, and last summer she noted that she was now on hospice, and then the e-mails stopped. In keeping with this understated woman, her service was private.

Mentor to Surly Luddites. Howard Angione was a reporter who somehow wandered into the emerging technology age at The New York Times, in the mid-1970s. With the reserved air of a theologian, he had to introduce temperamental reporters to the bulky Harris terminals now placed around the City Room. Sometimes these terminals would swallow articles whole, provoking profane tantrums from cranky news reporters like, well, like me. Howard’s motto was: “If I can teach Vecsey, I can teach anybody.” Which he could. After his missionary work in the City Room, Howard went to law school and specialized in elder law, until he became an elder himself. The NYT did not note the passing of the tutor who helped modernize the paper, but the Portland (Maine) Press-Herald did. Zone-Buster Poet. Stephen Dunn was a rather shy jump shooter who could beat down a zone defense. On one road trip, he heard two older Hofstra teammates discussing a novel, and he realized jocks could also be scholars – and later he began to write poetry, ultimately gaining a Pulitzer Prize. His later years were spent fighting Parkinson’s disease, which got so bad that he could not recite his own work. Our friend, once known as “Radar,” was deservedly included in the NYT’s gallery of notables in Friday’s year-end necrology. My Cousin Artie. From my earliest memories, I admired Art Spencer, my oldest cousin. He was so cool – riding a two-wheeler, driving a car one summer in rural Pennsylvania, with friends who had musty, mysterious barns amid lush corn fields, going to college, going into the military, marrying, starting a family. At family gatherings – some joyous, some sad – I had to practically pry out of him that he and Shirley had a flourishing crafts business, designing house signs – staples at weekend crafts exhibits near Ocala, Fla. The women in his family cared for him lovingly in his final months, and then staged – sign of the times – a Zoom service to honor an understated and artistic life. Agent and Friend. Philip Spitzer was my agent who negotiated a durable contract with a publisher and the manager of Loretta Lynn – a project in 1974 that turned out to be the book and the movie, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” I can still see Philip -- suave, part French, athletic, sitting on Berney Geis’s rooftop patio in Manhattan, holding his own, word by word, paragraph by paragraph, with two legalistic sharpshooters. We became family friends, his three children, my three children, good memories, even if the guy would never, ever, let me win a tennis set or a basketball game. Even after we did not work together, we stayed in touch, and as his health deteriorated, he passed the Loretta project to his capable oldest child, Anne-Lise Spitzer. This magnificent seven stands in for all the people in my life who passed in 2021. As far as I know, Covid did not figure in any of their passing – just the inevitable erosion of time, long and good lives, now ended. Our best wishes to all who read this tribute. As one often hears in corners of New York: Be Well. For many years, Marianne painted in the midnight hours, when the kids were asleep and I was on the road somewhere. After a few hours of sleep, she got up and made school lunches and checked her lesson plans and drove off to teach art.

At some point she produced this large painting, which wound up in a gallery in Manhattan, and then in friends’ apartment on the Upper East Side. But now those friends are downsizing, and no longer have room for the painting, so they graciously offered it back to the artist. In the middle of a pandemic, with no station wagon anymore, we did not see retrieving it and squeezing it into our house, already crammed with books and art and kitchen utensils. Marianne mentioned her dilemma to our West Side friends, who are redecorating their apartment in the 50s. They know her work, and were interested, but the painting had been wrapped, and was sequestered in the basement of the East Side building. So they accepted it, sight unseen. Then came moving day, part of the daily buzz of the city, good times or bad times -- folks clutching modest bags of clothing on the subway, other folks engaging gigantic moving vans that block side streets, out-of-town children of privilege who come clumping down the elevated train stairs with one wheeled suitcase in an “emerging” neighborhood, getting dirty looks from ladies in the local peluqeria whose rents are about to double. (I witnessed that in Bushwick two years ago.) Now our friends were joining the sidewalk shuffle, taking 45 minutes to walk across town, spotting “dog runners and dog strollers in the park, empty buses plying Fifth, a fit couple racing up and down the Met Museum’s steps. The ‘Ancient Playground” at 85th and Fifth still temporarily closed,’” as the lady half of the couple wrote. I had warned that if they tried to carry the painting across town, one of those classic crosswinds that scream out of a side street could pick them up, clutching the painting, and deposit them in Oz, or New Jersey. But it did not come to that, because when the East Side porter delivered the 6-by 4-foot package near the front door, they realized it was so sturdy that blithely carrying it across town – for fun, for exercise – was out of the question. Now began the quest for wheels. They tried shoe-horning it into a city taxi, but it was four inches too long, so they tipped the driver for his effort, and waved farewell. The super helped them carry it to a busy corner and left them to their adventure. They hailed two panel trucks and tried to cajole the drivers into making an excursion, but both apologized for being busy. A plumber parked nearby offered to help but needed an hour to set up his crew. Tired of standing on the corner propping up a large painting, they called a messenger service, New York Minute, which promised to drop it at their building, as they took a taxi back home. An hour later, the painting arrived and they set it on the terrace for a few hours to give germs time to die. They still had not seen the painting that had occupied several weeks of logistics that could have sent a spaceship to a far-off docking station. (Did I mention that Marianne, in her other life as matchmaker, a/k/a the shiksa shadchen, had matched these two friends, not so long ago?) “Unwrapped, it was love at first sight. It’s Marianne’s Geometric Period, mixed media watercolor and oil,” our friend reported. “It miraculously fit on the pre-existing hooks opposite our bed.” They took a photo – the miracle of the smartphone—and beamed it to Marianne, who immediately recognized it from the period, decades ago, when she found a makeshift table that could accommodate larger canvases. She has sold around 250 paintings, some now dispersed around the world. She may not recall the year or the circumstances of each painting, but she recognizes each painting, remembers the creation. She has won awards in juried shows, has placed her work in slide form or real-life form, in Manhattan galleries, has received respectful “keep-painting” receptions from major galleries, some of them part of the art hustle of recent decades, no names mentioned. It all came back to her, including the review in NYT’s Long Island Section, by critic Phyllis Braff: One feels and imagines the aura of the Grand Canyon, Notre Dame, a night sky, a fall landscape or a cemetery in visions that are executed through rather innovative manipulations of small squares made vibrant with mottled, transparent watercolor tones. Color selections that tend to be symbolic, and exacting schemes of dispersing the painted units, are both important in carrying the message. This painting, part of Marianne’s most active period, is now hanging in the bedroom of a fashionable apartment, home to many soirees with art-conscious New Yorkers. But the main reward came when the lady wrote: The painting is now the last the last thing we see at night, and the first thing we see in the morning. Joy. Marianne’s painting has made the daunting crosstown trek from the East Side to the West Side. Its journey has also brought us joy. * * * The review in the NYT by critic Phyllis Braff: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/09/nyregion/art-unexpected-messages-in-geomettic-form.html?searchResultPosition=1 The Kavanaugh hearings have reminded me of two milestones in my own life.

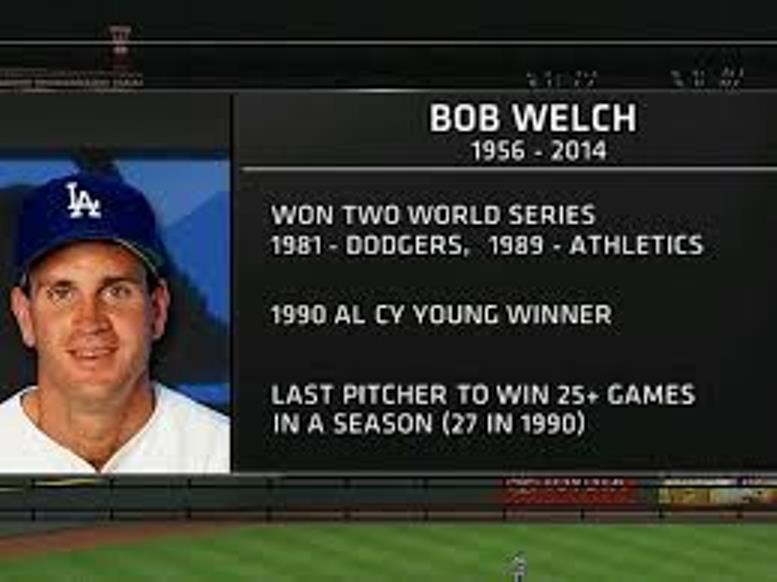

One milestone came in my last few years of full-court basketball, in my late 30s, with players ranging from recent high-school varsity players to elders in their 40s. From fall to winter to spring, every Monday in the late ‘70s, the players in “adult rec” changed in one wing of the locker room while the boys on the varsity changed in the other wing. Over a row of lockers, I could hear the current jocks talking about life and times, but mostly girls – that is, who did what, and how often, and with whom. It was graphic and it was personal. This was before social media. Whether it was true or not, it was out there. This did not sound like my high school jock experience in the 1954 and 1955 soccer seasons. I am told that teen-age sex had been discovered back then, but boys did not talk about it in open locker rooms. I went home and told our two daughters, both coming along in the schools, “Boys will talk.” And some girls would be treated as prey. My second milestone came up the other day when the nominee for the Supreme Court – the Supreme Freaking Court – was recalling his idyllic days as student-athlete in a prep school (a Jesuit school, at that.) He seemed to retain the impression that some girls were from their crowd while others were outside their “social circle.” (The Jesuit magazine, America, has withdrawn its support for Kavanaugh's candidacy.) What happened to the dignified lady who testified is now up to the FBI. What a wonderful idea -- calling in professionals instead of relying on dotty senators. The hearing reminded me of my week in a rehab center early in 1981, when I was 41. I was working on a book with Bob Welch, the young pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, who had gone into rehab after blanking out in alleys and hotel corridors on the road. Bob was now sober – had pitched well for the Dodgers in 1980 – and I wanted to know what rehab had been like for him. The center – The Meadows, in Wickenburg, Ariz., said I could attend for a week, but I would have to participate in group sessions, not merely observe. One of the first things I noticed at The Meadows was that some people started off accepting that they were powerless. They were sad, and tried to deal with the feelings that made them drink or take drugs or abuse sex. But others were adamant that they had no problem. Why were people saying these things about them? Why were they making up stuff? And most of all – with volume rising and face distended and arms flailing – why the f--- didn’t people believe them? Why was everybody against them? Bluster seemed to be their stock in trade. Ward off the accusations with a swat at the air, a sneer, a bellow. I learned a lot at The Meadows. The sessions shook off a few memories of shame when I drank too much, smarted off too much. I learned I did not have to drink when I didn’t feel like it, which is now almost all the time. I had a great teacher. My friend Bob Welch stayed sober (as far as I know), day by day, for the rest of his too-short life. He knew himself. He knew the nature of the beast. One time he and my teen-age son Dave and I were in a restaurant in Montreal, and Bob was doing the play-by-play of the dining room. “Look at that guy,” Bob would say. “He wants to pour for everybody. That’s so he can drink more. Watch.” Sure enough, the stranger would cajole his companions to top off their glasses, so he could refill his. I learned from dear friends like Bob Welch and my recent pal (he knows who he is) who fight off the beast, day by day, and acknowledge it, and share the struggle. The book, "Five O'Clock Comes Early." is still out there. C.C. Sabathia of the Yankees relied on it when he checked into rehab. I thought about Bob the other day when I was watching a candidate for the Supreme Court who, when confronted with touching testimony (if murky external details), resorted to baiting senators: What do you drink, Senator? Did you ever black out, Senator? Maybe that is the combative reaction of a former high-school jock who (as he reminded us a time or two) lifted weights and played hoops back then, all summer long. Doesn't seem very judicial to me. Channeling my late friend Bob Welch, I reacted to the visceral bluster on the screen. “Whoa,” I said. “Whoa.” There was so much horror in America from 9/11 that I certainly did not think about David Skepner. But every year when crisp weather reminds me of a lovely morning in 2001, I think about him.

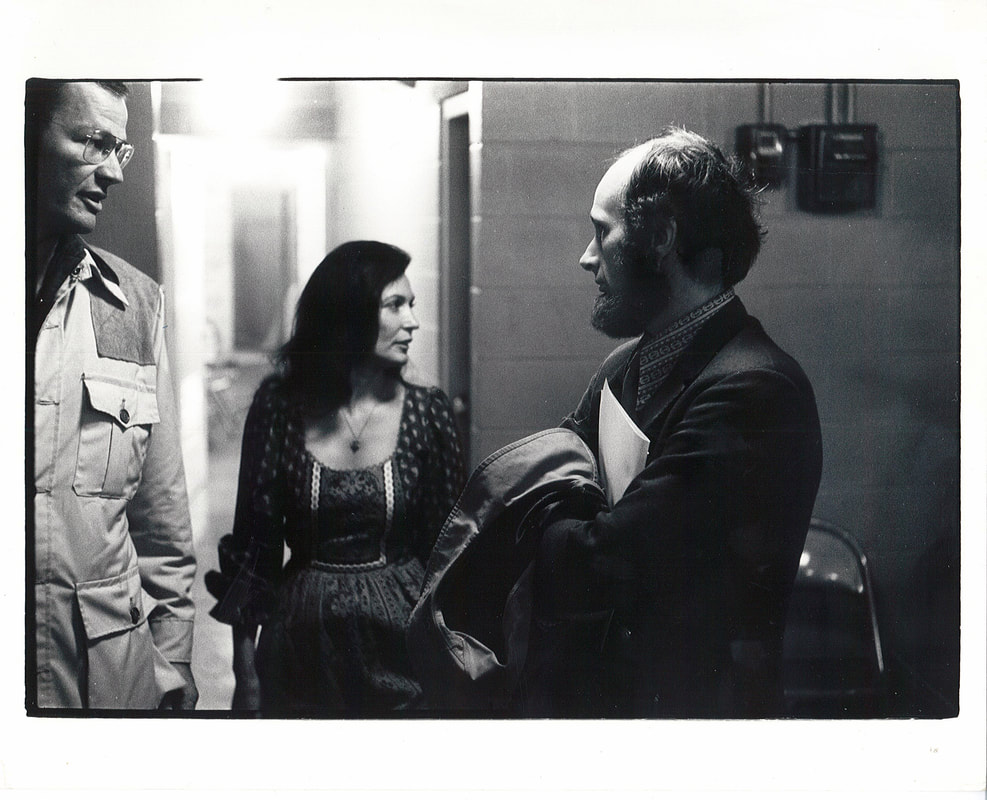

David was Loretta Lynn’s manager-for-life, a Beverly Hills guy come to Music City. He was assigned by the home office of MCA to supervise her career, and he moved to Nashville and helped turn her into a worldwide star. In 1972 he fielded a request from the New York Times’ Appalachian correspondent – me – for an interview with Loretta, who was already dominating country music on her charm, beauty and voice. He did not invent her but he made sure she got the attention she deserved. I knew her music, of course, and found out from a two-fisted county judge in Eastern Kentucky that Loretta had pulled her band off the road to play a benefit in Louisville for the families of 38 coal miners blown to kingdom come in the Hyden disaster I covered. I was touched by her zeal to make some money for her people. Loretta won the Entertainer of the Year award in October of 1972, the first woman to be honored. The next morning, she did the national dawn TV shows and then Skepner ushered me into her room where she was tucked back into bed. I got a great interview – everybody always did – and the great Charlotte Curtis gave it prominent display in the NYT. Two years later David decided the world needed a Loretta Lynn bio – and he promptly asked Pete Axthelm of Newsweek to write it. Ax had done a great cover story on Loretta but he couldn’t do the book (we would always laugh about that when we met) and so I got the call. That meant, time on the road with Loretta. David was the gatekeeper – a big dude, probably 6-foot-3 with matching persona and a big iron on his hip, as the song goes. I don’t believe he was ever in the service but he was a big military buff, who wore olive jackets and blue caps with Navy insignias and belonged to a pilots’ association. Travelling with Loretta, security was always an issue, particularly when Mooney Lynn, her husband, was not around. I had been around guns in the mountains, but whenever we were indoors David would put the huge pistol (I have no idea what type) on a nearby table. I asked him if he could point it in the other direction – and cover it with his ball cap -- and he laughingly obliged. David could be officious -- but he made things happen. Her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” leaped from her verbal ability into a best-seller, as David had known it would. And so did the movie, with so many talented people falling into place. A lucky boy, I was along for the ride. At some point, David and I became friends. I moved from Kentucky back home to New York and we stayed in touch. Whenever I went to Nashville, we would meet at a Thai restaurant near Vanderbilt and he would catch me up. In 1986, Loretta and David stopped working together – her call. He managed other acts (Dixie Chicks, Riders in the Sky) but whenever she needed professional advice – from somebody she could trust -- she would call David, and he was fine with that. Weeks after 9/11, I called a friend in Nashville for something or other, and she asked if I had heard about Skepner, which sounded ominous, and she filled me in: When 9/11 started to happen, David went into emergency mode. As a military guy, he undoubtedly saw this as war, and he wanted to be prepared. All circuits in full-red-tilt operation, he rushed down to gas up his car because…you never know…and as he stood there, pumping his own gas, he fell down, dead before he hit the ground. Normally, David Skepner’s passing would have been noted in Music City but not in those first horrible days. Eventually, an article said David had one sister, but gave no more personal details. Loretta went into a shell after Mooney passed in 1996 – so I never talked with her about David’s passing. But I used to call a few friends down there and we would talk about him as a force of life, who kept things together for Loretta. Now, every year when 9/11 approaches, I think about David Skepner. Of all the people who died that day, I knew him best. On his theory that it is not every day that a person turns 90, Frank Litsky threw himself a party the other night.

Frank drew over 40 old hands from the Times, who celebrated him – and our business, which was putting out the paper on deadline. Looking great, sounding great, Frank noted others in his nonagenarian state – Tony Bennett, Fidel Castro, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Cloris Leachman, Jerry Lewis, Mel Brooks, Don Rickles, just to name a few. (The overall list is impressive.) Colleagues from the 50’s and 60’s, Gay Talese and Bob Lipsyte, made lovely talks about Frank’s energy and knowledge and productivity. In an informal chat, I reminded Frank of my nickname for him -- Four-Fifty. This stems from when I came over from Newsday in 1968 with a lot to say, and Frank was the day assignment editor who shoehorned stories into the section. I would check in each day with proposals for lengthy rambles about the Amazing Mets or the post-Mantle Yankees, and Frank would cut me dead with the fatal words: “Four-fifty.” That is, 450 words Frank Litsky stifled my imagination and made it impossible to show my stuff, to the point that my career and the paper suffered terribly. He has never repented. We crowded into Coogan’s Restaurant in Washington Heights, near the armory which has been refurbished to house Frank’s beloved track and field. (The proprietor, Peter Walsh, himself a copy boy at the Times in the late ‘60’s, even serenaded us with a song in Gaelic.) We all had histories with each other, over the decades: Sports editors who had made tough decisions. Copy editors who had pulled stories together minutes before the press run. Reporters who had broken good stories. Columnists who had typed our precious little thoughts. Clerks and office managers who made the whole thing work. Margaret Roach, the journalist daughter of James Roach, the beloved sports editor of the ’60’s, was there. Joe Vecchione and Neil Amdur, two subsequent sports editors. Fern Turkowitz and now TerriAnn Glynn, who held the section together. All of us could, if we tried, recall snit fits and frustrations with some of the people we were now hugging. But what we remembered most was somehow letting the esteemed production people push the button on time. What we had in common was the identification with the physical product that people held in their hands, read seriously. It is in our blood. Frank Litsky, who covered Olympics and pro football and women’s basketball, has known good times and terrible times, and now he sat there, a wise old Buddha figure with a New York accent, with “the love of my life,” Zina Greene, listening to old stories, some true. One thing I learned that night was that in his alleged retirement, Frank has contributed over 100 obituaries of sports figures, sitting there in the digital can. I am betting all his masterpieces go over 450 words. Just saying. Altenir Silva, my friend from Brazil, had a one-minute play produced at the New Workshop Theatre, Brooklyn College, in June. It is called “She Loves Pepsi and He Drinks Coca-Cola.” Needless to say, it is about relationships. I told him it sounds like “Waiting for Godot,” only with a redhead with a Russian accent. Altenir has written for Brazilian television and has also written several movies, including the touching “Curitiba Zero Degree,” about four men whose lives intersect in gritty corners of a large southern city. The film has a hopeful message, rare anywhere. The trailer for the film: I was in awe of Sam Toperoff days into my freshman year at Hofstra College. From my workship with the athletic department, I knew he was a transfer basketball player, out of the service, waiting to play the following season.

Then he turned up in a sociology class, and he stood out. He was 5-6 years older than me and knew how to talk in class. I still remember Professor Nelson explaining the sociological concept of brothers and others – the circles of life, people we care about, people we don’t necessarily care about. “You, Toperoff, are my brother,” Professor Nelson said, “and the rest are others.” A hundred people in this huge lecture hall, and the professor knew Sam’s name. Toperoff started for a couple of seasons of varsity ball. My strongest memory of him is singing – maybe a Belafonte song? – in the locker room before a road game, nervous energy, channeled into song. He was a force. Stephen Dunn, the shooting guard, now a Pulitzer-Prize-winning poet, tells about listening to Sam and another teammate in a hotel room, talking about Moby Dick. Imagine. Not women or zone defenses, but words, concepts. (That was quite a team -- a novelist and a poet, starting.) Sam taught at Hofstra for 20 years and has written 13 books on extremely varied subjects, including the gripping Pilgrim of the Sun and Stars, about a Basque peasant who makes a pilgrimage to the Vatican. Sam also wrote sports for magazines and for 15 years worked for public television, most notably a travelogue series. My wife bought all of them. Now Sam lives in the French Alps (in a house he built) with his wife and daughter and grandson. He is a hero to his pals because he has continued to write. Lillian & Dash, his novel about the long affair between Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett, is being published by Other Press in July of 2013. Sam has gotten good advance attention, including a Kirkus review. The novel is available via Amazon and other sources. I've read it, and I love the dialogue and insight into two talented people from another time and place. It’s been a lot of decades; Toperoff still scores. In the Copacabana section of Rio de Janeiro, Altenir Jose Silva imitates John Sterling.

Silva is a writer with television and movie credits in Brazil, and he also writes in English, including a recent play about F. Scott Fitzgerald. He also pays around $70 a year to subscribe to a web site that streams Yankee games, direct from New York. He works on his English by shouting, “YANKEES WIN! Thuh-h-h-h-h Yankees! Win!” (It’s only fair. Some Americans imitate soccer goal calls by South Americans.) Silva and I become email pals, and he is a frequent contributor to this site. Recently, he visited New York for a screenplay course and he and his wife, Célia, took their last big trip before she delivers their first child, after years of marriage. We met for the first time at Foley’s, the Irish baseball pub on W. 33rd St. and he had already bought tickets to last Saturday’s Yankee game. Altenir and Célia were glad to hear Curtis Granderson was back in the lineup after his injury; Altenir gave his version of John Sterling’s rendition of “The Grandy-man can, oh the Grandy-man can.” From the nation of Pelé and Sócrates and Romario and Neymar, a man sings of Curtis Granderson. The very nice publicity director of the Yankees, Jason Zillo, arranged for a greeting for Altenir and Célia on the message board before the home half of the third. I advised them to have their cameras ready. They are great tourists. On their last night here, they caught Woody Allen’s weekly appearance at the Café Carlyle with The Eddy Davis New Orleans Jazz Band. Now they are back home in Rio. Instead of imitating Tom Jobim or Caetano Veloso, Altenir warbles along with John Sterling. We recently visited friends for a lovely dinner and conversa-tion. The highlight just might have been seeing a new cycle of work by our hostess, Rosa Silverman. The nice thing about having a web site is being able to display art, just because. (Note: My friend and mentor, Stan Isaacs, the long-time Newsday sports columnist, is temporarily without an outlet due to web problems. He always has a place here. GV.) Ozzie Guillen Struck a Few Chords The flap over Ozzie Guillen’s comments considered sympathetic to Fidel Castro reminds me of George Romney. Not Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential candidate, but his father, George, who was a governor of Michigan and had presidential aspirations of his own that petered out. George Romney pretty much eliminated himself from contention for the 1968 Republican nomination because of one comment. In mid-1967 he reversed his earlier support for the Vietnam War; he said he had been brainwashed by American generals. As we all came to realize, Romney was correct to have turned against that disastrous war, but the American people didn’t want to hear it. Exit Romney. Now, along comes the colorful Ozzie Guillen saying things that have more than a tinge of truth to it, but also angered many people because he showed some sympathy for Fidel Castro. Guillen is the new manager of the Marlins of Miami, the city known for having a rabid anti-Castro community. Anything positive said about Castro feeds the hatred of people who have never forgiven Castro (the left wing dictator) for replacing Fulgencio Batista (the right-wing dictator) in 1959. Here is what Guillen told a Time Magazine internet edition website: “I love Fidel Castro. I respect Fidel Castro. You know why?. Many people have tried to kill Fidel Castro in the last 60 years , yet that mother ------ is still there.” Indeed. Castro is living through his 11th American President in Barack Obama. The anti-Castro oldsters jumped on Guillen for actually saying he loved Castro. So did some of the politicians running for office now, because the anti-Castro community in Miami has been so powerful for so long. It has cowed not only local politicians but Presidential candidates. The enigmatic Guillen most likely wasn’t thinking about all that. Castro is no civil libertarian. He has executed people who worked against the regime. But consider Castro’s background. Almost from the time he took power and edged toward an alliance with the Soviet Union in the face of opposition from the United States, he has had to worry about being deposed by the United States. This is not paranoia. In April, 1961, President Kennedy supported the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba by anti-Castro partisans determined to take back their former homeland. The invasion was a disaster but it alerted Castro to ever be on the alert against further attempts to subvert his regime. He has been ruthless at time in eliminating opposition, because the opposition centered in Miami has never stopped calling for the removal of Castro. We still have an embargo against Cuba that hurts, not Castro, but ordinary Cubans. I was in Cuba some 30 years ago. I found that the Cubans hated the United States government for trying to bring down Castro, but loved Americans. We were treated well wherever we went. We heard criticism of Castro by people who didn’t seem to fear retribution for the comments. Most Cubans cared more about making a living than worrying about the lack of civil liberties that were the concern of the few genuine patriots who objected to Castro’s excesses. Guillen is a colorful gent, who has often made outrageous remarks that were as confusing as they were amusing. This time he made the mistake of getting himself involved in the super-charged area of Cuban politics. His comments were not so much for Castro, the politician, as Castro, the man who outlasted all the people who have tried to kill him. Many plots were born in the Miami Cuban area. Gullen said he loved Castro, sure, but he also called him a mother ------. That’s hardly the comment of a deep political thinker. It could be argued that he had the First Amendment right to say anything he wanted. But it doesn’t work that way in the world’s most heralded democracy because we are—from Eisenhower to Obama--bedeviled by the anti-Castro faction. So Guillen soon found out he had stepped in it and had to apologize for his comments. The Marlins suspended him for five games. And before a press conference in which he grovelled an apology, management surrounded him with people who knew first hand of Castro’s brutality. Guillen cried as they spoke. “I know I hurt a lot of people,” he said. One of the offshoots of the controversy was the revelation that Miami, for all its anti-Castro mania, is changing. At a protest calling for Guillen”s removal, only 200 people came out. The group leading it, a Miami report said, was a fringe organization always looking for reasons to break out the picket signs out of their car trunks. The average age of those holding the signs seemed over 70. Little Havana used to bristle with the antennae of eight or so anti-Castro radio stations. There are two left. Most people seemed to accept Guillen’s apology. Suddenly there is room in Little Havana for nuance. I have been surprised by another fallout of l’affair Guillen: criticism of the United States. Bryant Gumbel said on his HBO show, “And while there is no way to defend Ozzie or the blatant insensitivity of his remarks, let’s not pretend there’s no politics at work in some of those calls for his ouster. Whipping up a frenzy over slights real and imagined is a play straight out of a far-right handbook; Florida’s electoral clout has often given Fidel’s critics far more leverage that their arguments merit.” An unidentified critic of the United States added this heresy on Google: “While Castro is undeniably guilty of subverting the civil liberties of Cubans and he did kill many political dissidents, the scale of his crimes does not even approach that of the crimes of the United States government against Cuba and many Latin countries. In reality our opposition to the Castro regime has everything to do with his unwillingness to play ball like his predecessor Batista. “The reaction to Guillen’s comments just further illustrates the unwillingness of Americans to condemn the truth about our own transgressions. We need to realize how ridiculous we sound when we criticize the human rights record of another country when one considers our own.” If we’re lucky in life, we meet somebody who teaches us just by existing; I’ve been fortunate to have two for the price of one.

Stan Isaacs acted as a mentor when I started out taking high-school basketball games over the telephone at Newsday. He was the iconoclastic sports columnist, one of the best in the business, and he somehow found time to praise and criticize, escorting me to ball parks, showing me how it all worked. Then Stan invited us to his home, to meet his wife. It did not take long to recognize that Bobbie Isaacs was always going to be the adult in any room. In my early twenties, I found myself watching her, how she listened, how she smiled, how she kept the conversation going, something like a point guard who keeps the ball moving, but does not need to take a shot. We could be talking politics or the newspaper business or sports, with me grumbling over which manager wasn’t talking or which player was a good interview. Bobbie always seemed interested in what we were saying. She was a social worker, trained to observe, meeting families with serious troubles, She did not talk about her work, at least when I was around. It took me a while to figure out the kind of heavy-duty cases she handled. I watched her with Stan, and their three daughters, and their smart and involved friends. This is how a grownup acts, I thought. My wife the painter managed to establish that Bobbie was also an artist, a quilter of real talent. Until last week I did not know she was also an ace at crossword puzzles. Stan and Bobbie were also examples in the way they handled retirement, giving up their warm home on Long Island, finding a complex outside Philadelphia, with facilities that ranged from independent living to medical care. As usual, their friends were interesting and diverse. Bobbie and Stan became part of the daily life at their new home, taking part in the senior-olympic competitions. I found out only last week that, social worker to the core, Bobbie had arranged for people and their pets to visit the homebound. When I heard that Bobbie’s health was deteriorating, I called her a few months ago. She was the same person I had known for half a century -- asking about my family, my work. How was she? A little tired, she said. She passed on Jan. 22 at the age of 82. Our thoughts go out to Stan, Nancy, Ann and Ellen and their families. Thank you for sharing Bobbie. |

Categories

All

|