|

There was so much horror in America from 9/11 that I certainly did not think about David Skepner. But every year when crisp weather reminds me of a lovely morning in 2001, I think about him.

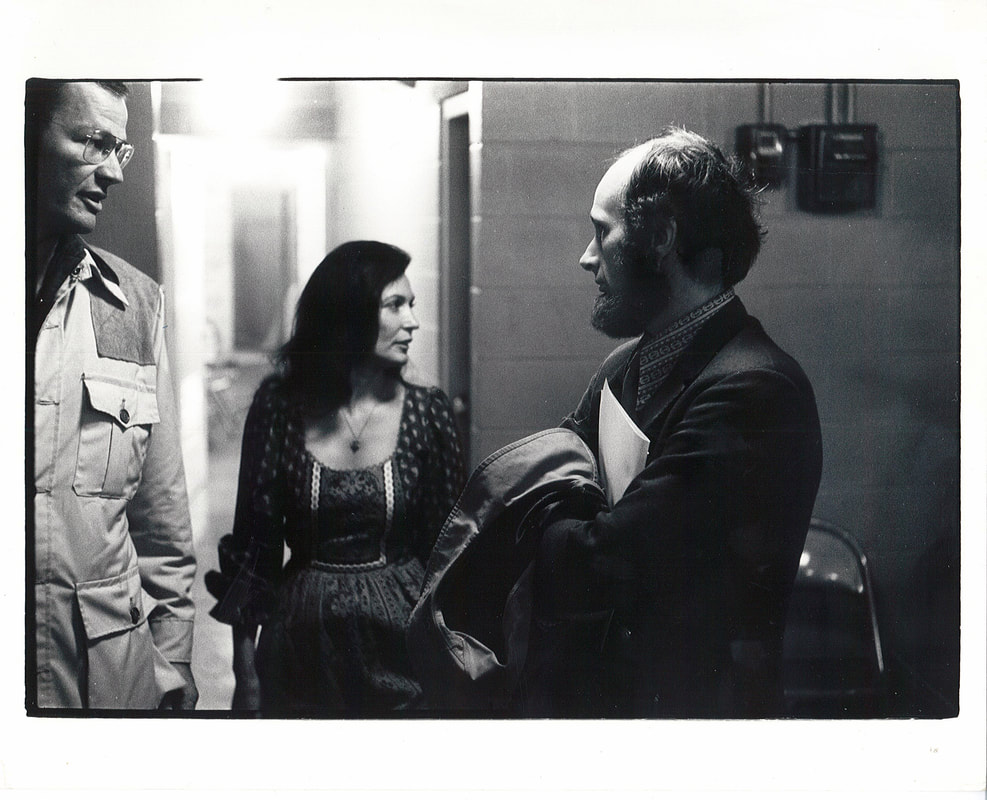

David was Loretta Lynn’s manager-for-life, a Beverly Hills guy come to Music City. He was assigned by the home office of MCA to supervise her career, and he moved to Nashville and helped turn her into a worldwide star. In 1972 he fielded a request from the New York Times’ Appalachian correspondent – me – for an interview with Loretta, who was already dominating country music on her charm, beauty and voice. He did not invent her but he made sure she got the attention she deserved. I knew her music, of course, and found out from a two-fisted county judge in Eastern Kentucky that Loretta had pulled her band off the road to play a benefit in Louisville for the families of 38 coal miners blown to kingdom come in the Hyden disaster I covered. I was touched by her zeal to make some money for her people. Loretta won the Entertainer of the Year award in October of 1972, the first woman to be honored. The next morning, she did the national dawn TV shows and then Skepner ushered me into her room where she was tucked back into bed. I got a great interview – everybody always did – and the great Charlotte Curtis gave it prominent display in the NYT. Two years later David decided the world needed a Loretta Lynn bio – and he promptly asked Pete Axthelm of Newsweek to write it. Ax had done a great cover story on Loretta but he couldn’t do the book (we would always laugh about that when we met) and so I got the call. That meant, time on the road with Loretta. David was the gatekeeper – a big dude, probably 6-foot-3 with matching persona and a big iron on his hip, as the song goes. I don’t believe he was ever in the service but he was a big military buff, who wore olive jackets and blue caps with Navy insignias and belonged to a pilots’ association. Travelling with Loretta, security was always an issue, particularly when Mooney Lynn, her husband, was not around. I had been around guns in the mountains, but whenever we were indoors David would put the huge pistol (I have no idea what type) on a nearby table. I asked him if he could point it in the other direction – and cover it with his ball cap -- and he laughingly obliged. David could be officious -- but he made things happen. Her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” leaped from her verbal ability into a best-seller, as David had known it would. And so did the movie, with so many talented people falling into place. A lucky boy, I was along for the ride. At some point, David and I became friends. I moved from Kentucky back home to New York and we stayed in touch. Whenever I went to Nashville, we would meet at a Thai restaurant near Vanderbilt and he would catch me up. In 1986, Loretta and David stopped working together – her call. He managed other acts (Dixie Chicks, Riders in the Sky) but whenever she needed professional advice – from somebody she could trust -- she would call David, and he was fine with that. Weeks after 9/11, I called a friend in Nashville for something or other, and she asked if I had heard about Skepner, which sounded ominous, and she filled me in: When 9/11 started to happen, David went into emergency mode. As a military guy, he undoubtedly saw this as war, and he wanted to be prepared. All circuits in full-red-tilt operation, he rushed down to gas up his car because…you never know…and as he stood there, pumping his own gas, he fell down, dead before he hit the ground. Normally, David Skepner’s passing would have been noted in Music City but not in those first horrible days. Eventually, an article said David had one sister, but gave no more personal details. Loretta went into a shell after Mooney passed in 1996 – so I never talked with her about David’s passing. But I used to call a few friends down there and we would talk about him as a force of life, who kept things together for Loretta. Now, every year when 9/11 approaches, I think about David Skepner. Of all the people who died that day, I knew him best.

Janet Vecsey

9/10/2017 07:00:14 pm

What a sad story. But of course interesting. Want to share it on FB, but unable. I saw it earlier (maybe Laura shared). But the stories go by so fast it's hard to get them back.

Mendel

9/11/2017 10:48:59 am

Beautiful, George. Careful descriptions in the face of indiscriminate violence makes the world a kinder, more gentle place. 9/11/2017 11:51:11 am

George—I always enjoy your ability to put meaning into the lives of the many important unknown people behinds the scenes.

George Vecsey

9/11/2017 03:49:22 pm

Thanks to Janet and Mendel. Alan, when the movie came out, I was invited to the "grand opening" in Louisville, where I used to live.

Altenir Silva

9/15/2017 08:51:41 pm

Dear George,

bruce

9/19/2017 10:05:13 am

george,

Russell

2/12/2018 10:25:09 pm

I stumbled upon this tonight by chance and it fills my soul. David was my Artist Manager professor at Belmont University here in Nashville in the late 1990’s. I was quiet but David pressed me out of my shell.

George Vecsey

2/13/2018 08:36:42 am

Dear Russell: Wow, what a lovely note. I'm so glad you found this. I didn't hear about David for many days, until Loudilla Johnson called me and asked if we were okay, and then she asked, "Did you hear about David Skepner?" At that point, she said, there hadn't been anything in the Tennessean (when it was still the Tennessean and had not been Gannett-ized) I'm glad there was a memorial for David. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|