|

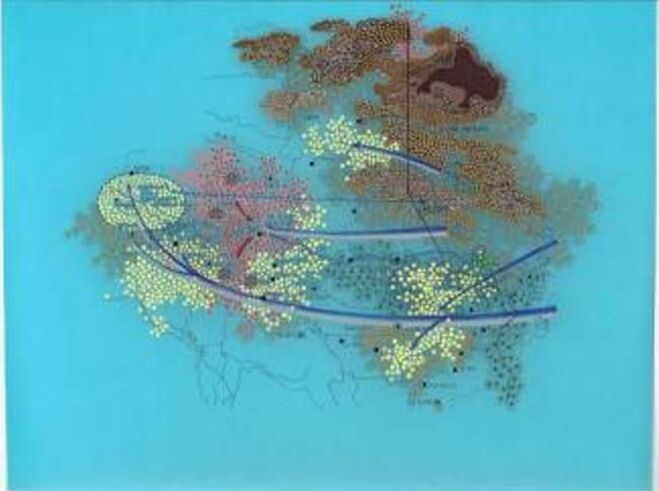

There is a current art exhibit in Washington, D.C., that I am hoping to see -- “Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975,” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Holland Cotter in The New York Times calls it “protest art” from the American point of view. But the “second, smaller” part of the show I most want to see is “Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past Is Prologue,” a view of the Vietnam War era through Vietnamese eyes – “far more than a mere add-on,” as Cotter put it. The Vietnamese people experienced that war – in some ways 180 degrees differently -- but it is safe to say all suffered. In 1991 I visited “post-war” Vietnam with a small group involved in child care. My wife was doing vital volunteer work by frequently visiting India but she also visited Thailand and the Philippines. I joined her on the trip to Vietnam to deliver goods to a hospital and visit facilities in both “North” and “South” Vietnam. I was most definitely not there to work or act like a journalist, but I could not help looking and listening to how “The American War” had impacted Vietnamese lives. Saigon, now called Ho Chi Minh City: We met a doctor doing complicated surgery. He let us gown up and observe a complicated facial procedure done by a visiting American doctor, the mutual language in the operating room being French. We got to spend enough time with the doctor to learn he had been on the “wrong” side when the North took over, and was sent to a camp deep in the countryside. I gathered that his family had assets, and he had a great reputation, and he was released from the camp and allowed to resume his profession, refreshing his skills at major hospitals in Asia. He was an asset. In a relaxed social setting, the conversation got around to how he was able to put the war behind him, to function, to move on. I totally paraphrase his answer; it has been a long time, after all. He said you cannot live in the past, you have to get back to “normal” as smoothly and quickly as possible. When I (subtly, I hope) asked about the lost years in the camps, he showed no bitterness. He was still a surgeon, putting people back together again. Life went on. Hanoi Region. We worked our way up north (baguettes and coffee on the beach; ancient ethnic villages; a growing crafts shop outside Da Nang) and we flew to Hanoi. On a chilly day, we took a jitney out to visit a rural orphanage. Our interpreter was a woman around 30 who worked in the sciences and was fluent in English. I happened to sit next to her. Far into the countryside, I noticed circular ponds scattered on the flat land. I asked the interpreter what the waterholes were for – fishing? rice? source of irrigation? Actually, she said, with no trace of emotion or agenda, they were holes left over from bombs. She did not mention Richard Nixon or Henry Kissinger or the “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi and Haiphong in late December of 1972. She remembered, she said casually, living at a school, and hearing the bombs, and later discovering children her age had been killed or injured. I did not ask any other questions. The orphanage was shabby, but the workers were doing the best they could. They let us hold children as we walked around. They had a handle on each child, would not release children for adoption if relatives claimed them. We were bringing some aid, and people were courteous. A young worker pointed at my ball cap, from the 1990 World Cup, and he said, “Maradona,” and I gave him the cap. And then we flew on. Now I read about the show at the Smithsonian about the remaining terrible divisions in the United States over the Vietnam War. I hope to see that show, as well as its companion piece about Vietnamese reaction to the American War – “more than an add-on,” indeed. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/04/arts/design/vietnam-war-american-art-review-smithsonian.html Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past Is Prologue: https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/chung My past articles about John McCain, American hero, and Vietnam: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/category/vietnam My article about the excellent crafts shop outside Da Nang: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/-happy-lunar-new-year Since I first wrote this piece on Saturday morning, my pal Mike Moran dug out the original column I wrote from my interview with John McCain in 1999. This is it:

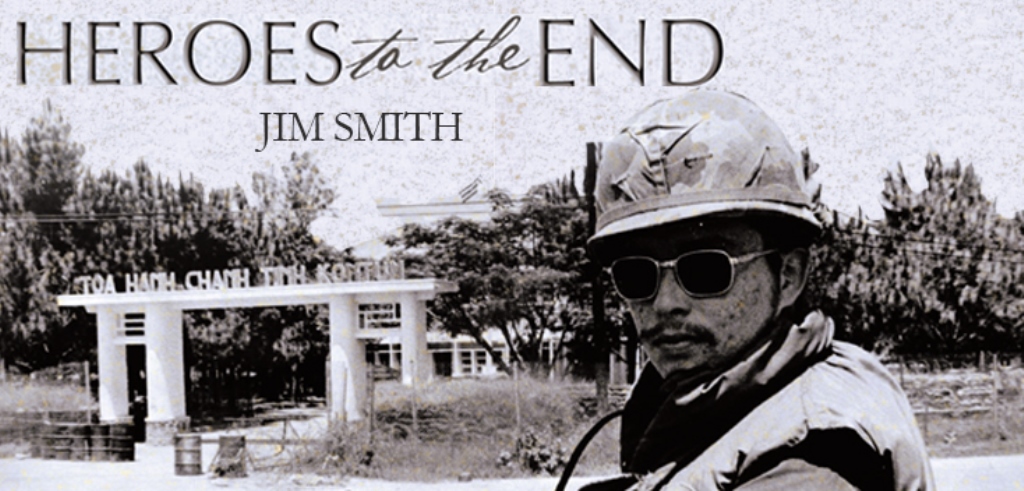

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/15/sports/sports-of-the-times-samaranch-wise-to-duck-the-senator.html 1. We all know how John McCain crashed into North Vietnam and was held and tortured for five-plus years. We’ve all seen the photos of his broken body, and we’ve all seen examples of his unbroken spirit. 2. My wife was on one of her child-care missions to India in the early ‘90s, and she sat next to a man on the flight out east. He said Sen. McCain was the leader of some vets who provided needed goods to Vietnam because they believed in putting something back. He gave my wife his card and said they could help ship material to orphanages or hospitals in Vietnam. 3. I was covering a Senate hearing into the International Olympic Committee. (Sen. McCain pretty much blasted an American Olympic official for a flip answer.) I had an interview scheduled with him at lunch break, and he disarmed me by chatting about sportswriting – a good politician, for sure, and good company. I said I knew something about him – and I told about my wife’s flight with McCain’s Vietnam-vet buddy. I asked the senator why, after what had been done to him, did he help provide goods to Hanoi? With his broken arms and shoulders, he gave a shrug that I can only describe as eloquent. The shrug said, it’s the right thing. (Then he went off again on the I.O.C. -- John McCain temper in action.) 4. I was watching live during the 2008 campaign when the lady in the red dress labelled Sen. Obama “an Arab,” and I saw John McCain’s instant reaction as he politely reclaimed the microphone, backed away, and said: “No ma’am. He’s a decent family man, a citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign is all about.” Sheer grace under pressure. 5. I had forgotten this until Brian Williams played it on MSNBC Friday night. At McCain’s concession speech in 2008, he began this way: My friends, we have come to the end of a long journey. The American people have spoken, and they have spoken clearly. A little while ago, I had the honor of calling Sen. Barack Obama — to congratulate him on being elected the next president of the country that we both love. In a contest as long and difficult as this campaign has been, his success alone commands my respect for his ability and perseverance. But that he managed to do so by inspiring the hopes of so many millions of Americans, who had once wrongly believed that they had little at stake or little influence in the election of an American president, is something I deeply admire and commend him for achieving. And he went on from there, more about the historic side of the election than about himself. I know he probably had somebody good writing the speech, but he delivered it, and he delivered it well. 6. Early on July 28, 2017, with Sen. Mitch McConnell glaring at him, Sen. McCain issued a thumbs-down on the proposal to gut the Affordable Care Act, known as Obamacare. He said the proposal did not meet his personal test. This means millions of Americans continue to receive medical care. 7. Earlier this month, the president of the United States talked 28 minutes about a defense-spending bill. The bill was named, by Congress, for Sen. John McCain, who was home in Arizona, dying of brain cancer. The president, still in office as of this writing, never mentioned the name of John McCain, American hero. 8. The latest news is that right through the weekend, the president, still in office as of Monday morning, did not have a good word to say about the life and death of a real American hero. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/26/us/politics/trump-mccain-funeral.html The one thing I forgot to say, explicitly, in the first version of this piece is how much I liked John McCain in person, and how I kept saying, during his campaigns in 2000 and 2008 and even when I was exasperated with some of his stands: "He's really a good guy." Our prayers are with Sen. John McCain and his family.  John Paul Vann, July 2, 1924 - June 9, 1972. Photo by Jim Smith John Paul Vann, July 2, 1924 - June 9, 1972. Photo by Jim Smith Jim Smith and I used to goof around in the Newsday sports department. He was going to college and covering high-school sports, just as I had started. Then he came up with No. 34 in the draft lottery and wound up in Vietnam, first as a typist, then on guard duty, then covering the war for Stars and Stripes. When he came back, he was different. They all were, the ones who came back. Years later, in 1991, my wife and I were in Vietnam through her volunteer child-care mission, and I came back with new friends and mostly good memories. I saw Jim at a game, and offered to show him photos. He shuddered. Didn’t want to go there. Now Smith is 67 and retired, and has written a touching and valuable book, “Heroes to the End: An Army Correspondent’s Last Days in Vietnam,” published by iUniverse, also available on e-book. The words come back. Tu Do Street. Hootch. Charlie. Tunnels. ARVN. Words from history. Words people live with. Jim is very clear about the journalism he produced, under orders to write only positive stories. But he has fleshed out the details with memories and notes he stashed and letters he sent home. He makes it clear that he was no hero. He had only four months up close to the fighting, in 1972, when casualties had been downsized, and he only began inching closer to combat near the end, so he would know what it was like. He came under fire twice, never fired a shot. Most Vietnam books go for the big picture – how LBJ and McNamara and Westmoreland and so many others ignored and misrepresented and lied. Smith’s book concentrates on the people who did the dirty work; some thought they should go harder, others thought it was all a waste. Smith fluctuated from dove to hawk. He kept his hair fairly short, so officers would give him stories. He concentrates on the mundane, the down time, the bitching, the carousing, but the old horrors creep in, nevertheless. Mostly he saw the humanity – some young Americans who discovered they were quite good at firing a machine gun from the door of a helicopter or seeking out Vietcong in the brush. They were warriors. Others were not. Smith was a reporter, glad to get back to base, to Saigon, to his apartment and civilian clothing and the girlfriend he almost brought home with him. The closest thing to a big picture comes from meetings with Lt. Col. John Paul Vann, who questioned the war and later was the hero of Neil Sheehan’s Pulitzer-Prize winning book, “A Bright Shining Lie.” “I had more respect for Mr. Vann – for that is what I always called him – than for anybody else I met in Vietnam.” After Vann died in a helicopter crash, Smith held back from punching a captain who said Vann had been a showoff. Smith displays admirable journalistic curiosity about the South Vietnamese, Montagnards and South Koreans he observed in combat. Then he came home to cover local news and we resumed goofing around during a fractious school-board feud in Great Neck. (How petty it must have seemed to a reporter back from war.) He married a colleague from Newsday, Lynn Brand, and they have a son, Peter. In retirement, Jim Smith is on the board of United Veterans Beacon House and is donating the profits from his book to veterans’ causes. He served. As he reminds us of that war, I would say he is inching closer to hero status all the time. Bruce Logan served two tours in Vietnam as an officer, and counted himself lucky when he returned to the United States. Now he and his Canadian wife, Elaine Head, consider Vietnam a second home.

Some Americans go back to confront their bad dreams in the cities and countryside. They are often touched by the conciliatory tone of word and deed. In a village outside Hanoi, Logan and Head were invited to a feast at the home of a woman named Phuong. In a matter-of-fact way, she described President Nixon’s Christmas bombing of 1972, the bodies and the rubble. The former officer expressed his sorrow for the carnage. “In response, Phoung turned her misted eyes to mine, laid her hand on my forearm and said, ‘I am so glad that you did not die in the war and that we are here to have dinner together in my house.’ “At that, everyone had a silent cry, for long ago pain, for the moment we had shared, and for the gift of forgiveness in Hanoi.” Logan and Head tell many stories like this in their book, Back to Vietnam: Tours of the Heart, published by JOTH Press, Salt Spring Island, B.C. and First Choice Press of Victoria, B.C. My wife and I had similar experiences in 1991 when we were visiting Vietnam as part of her child-care work. People casually divulged details of the war – but only if we asked. Mostly they demonstrated reconciliation, north with south, Vietnamese with Americans. Not everybody goes back. I have friends who lived through terrible times in Vietnam and do not care to go back. I was never there in wartime; I understand. I had a nice visit with Sen. John McCain once, and asked why he and his buddies help send goods to Vietnam. He shrugged, quite modestly, suggesting it was the right thing to do. I think about that when I see him on television. There is a good man in there. Like many combat veterans, Bruce Logan kept the war inside him, but he and his second wife, Elaine Head, visited Vietnam in 2006 with a group of veterans and their families. The book has touching stories of finding old foxholes, places where soldiers and civilians died, where horrible memories live, tempered by the forgiveness of the Vietnamese, that sometimes feels like a miracle. The glorious byproduct of the visits was gaining a family. In the World Heritage town of Hoi An, just outside Da Nang, Logan and Head met Le Nguyen Binh and his wife Quyen, who operate Reaching Out, a distributor of hand-crafted goods made by people who might be consider disabled. My wife and I have purchased some of their high-quality goods. (I wrote about Binh and Quyen in a previous post.) Binh and Quyen have made a standing offer for Logan and Head to live in Hoi An, and be cared for in their old age, perhaps even be cremated there. Not yet, Logan and Head say, politely. They still conduct tours for Americans who need to return to Vietnam. Their sweet book is graced by their anecdotes, their adventures, their bond with their other home. Every year on March 3, a few aging fraternity brothers gather among the plain white headstones of Long Island National Cemetery to remember Walter W. Rudolph. He died instantly on that date in 1969, a first lieutenant rushing to rescue a fallen comrade in Vietnam. They talk for a while, and then Jerry Lambert, the organizer of the pilgrimage, reads a portion of the Gettysburg Address: But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate -- we can not consecrate -- we can not hallow -- this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. This is a recent ritual, less than a decade old. Every fallen member of the military deserves no less – friends who remember, friends who show up, mourning the early death, perhaps even shuddering at the ambiguities of that war. A friend of mine goes home to West Point every Memorial Day, visits the graves of classmates who died in Vietnam. I think he said the total is somewhere in the mid twenties. Showing up is important. Jerry Lambert remembers his friendly, open brother from the Upsilon Gamma Alpha fraternity at Hofstra University, who sometimes wore the olive R.O.T.C. uniform around campus. Lambert does not remember much controversy about Vietnam in 1963, although surely some people were beginning to question the war by then. He recalls that some members of the R.O.T.C. were “gung-ho,” but others, like Walter Rudolph, “saw the military as a way to serve, possibly a career. In those years, they weren’t thinking about going to war in Vietnam.” So Lambert never had The Conversation with his friend about why the United States was escalating the war in Vietnam. There was no shadow over their two years together on campus. Lambert was older, having left a seminary to enroll in Hofstra, learning he would have to take two years of R.O.T.C., surprised to find he could fire a rifle fairly well. Walter Rudolph was a psychology major, a member of the track and field team, a blocking back on the UGA touch football team that did well against the jock fraternities. “The girls liked him,” Lambert said. Rudolph had a visceral sense of humor, one time picking up Lambert’s leprechaun physique and holding him overhead, like modest free weight. “He came from the North Shore,” Lambert said, referring to Manhasset in Nassau County, whereas Lambert still lives in what he describes as a more modest section of Westbury in the middle of Long Island. His fraternity brother carried himself with a sense of assurance. Officer material. Lambert recalls his own mandatory trip to Whitehall Street, the recruiting center in lower Manhattan, immortalized in Arlo Guthrie’s Alice's Restaurant. A doctor, new to the military, told him he had a heart murmur and said, “You can go home now.” The enlisted men on guard collared Lambert at the door, and told him, wait a minute buddy, he had to go through the procedure. But within a few hours, he was officially out of the military. He assumes he would have served if cleared. Sometime in August of 1969, Lambert heard that his fraternity brother had been killed in action in Gia Dinh – then a separate city just outside Saigon, now incorporated into greater Ho Chi Minh City. “Why Walter?” Lambert remembers thinking. “That awful war got him.” Rudolph became one of the estimated 58,000 Americans killed in Vietnam. Hofstra put up a plaque to honor its dead on the former gym on the main quadrangle, and organized a scholarship honoring Rudolph and Stephen B. Carlin, another fallen Hofstra soldier from that era. A decade ago, Lambert suffered through a personal depression, but he came through it. One day he and his wife, Judy, were visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial -- Maya Lin’s Wall in Washington, D.C. He had heard criticism of the undulating wall, set pretty much below surface level, like entering some other world, and he was prepared to hate it. Instead, he instantly felt it was one of the most beautiful monuments in the world. He found his friend’s name, placed his fingertips on it, and “somehow, Walter’s name started to transform me. I could feel my self-involvement start to go away.” Lambert, 71, and his wife operate their own company, bicycleposters.com, and frequently travel to cycling events, including charity rides organized by the Lance Armstrong Foundation; a cousin of his died young of cancer. He is something of an organizer. Sometime around 2003 or 2004, he rounded up some other old members of UGA, which has since been folded into TKE, a national fraternity. “I was embarrassed at not doing this thing sooner,” Lambert said. The visit to the cemetery usually includes Bob Gary, Frank Pittelli, Paul Koretzki and Tony Galgano, all fraternity brothers from the early 60’s. The white headstones stretch in all directions on the flat earth of central Long Island. Many have crosses; some have the Star of David. Some service members died in action; others died in old age; some spouses are buried alongside them. The cemetery is plain and utilitarian, with few flowers or stones or other decorations, at least in late winter, but the cemetery is inclusive in the best sense. There is no politics, no history, no judgments. When Lambert escorted me to his buddy’s headstone last week, I kept hearing the mournful voice of Johnny Cash, the American icon, who would have turned 80 on Feb. 26. In his classic Vietnam song, Drive On, Cash wrote: He said, I think my country got a little off track, Took 'em twenty-five years to welcome me back. But, it's better than not coming back at all. Many a good man I saw fall. And even now, every time I dream I hear the men and the monkeys in the jungle scream. Drive on… Americans are getting the hang of welcoming our people back. I’ve seen Vietnam guys at recent military funerals I covered – not quite regulation uniform, longish hair, letting their freak flag fly, the air of the outsider still with them. Drive on… Maybe soon New York City welcomes back the men and the women from Iraq, and after that from Afghanistan. Out on Long Island, on the anniversary of Walter Rudolph’s death, Jerry Lambert and his brothers will stand guard. * * * Note Below: Cash's version on American Recordings has way more kick to it: While waiting for Tet to start on Jan. 23, I think about two friends of mine from the modern Vietnamese diaspora.

They have never met, but both are making a success of their lives in this new age. Binh sells gorgeous crafts from Hoi An town, near Da Nang. Qui sells delicious pancakes and shrimp pho in St. Louis. I met Le Nguyen Binh while accompanying my wife on a child-care mission to Vietnam in 1991. We were walking through the coastal village of Hoi An, part of the Cham ethnic empire, with a cluster of residents following us. I noticed a young man in a wheelchair, smiling, listening intently, keeping pace with us. We started chatting in English, and it wasn't hard to figure out that with his language skills and intelligence and interest in computers, he was going to find his place as Vietnam became part of the modern world. We traded names and numbers, and stayed in touch. Now Binh runs an outfit called Reaching Out Vietnam, which employs people with disabilities who make jewelry and scarves and other goods. He has also founded Tien Bo (Progress), a self-help group for able-bodied people, and has also founded a computer training center. This story gets even better. Binh has since married Quyen, and they have a son named Vung, which means Sesame. A few years ago, Binh flew to a conference in Washington, D.C., and arranged a side trip to New York, staying at the very hospitable Crowne Plaza Hotel near LaGuardia Airport, where he was instantly the star resident. I could not meet him the first day, so he took off on a sight-seeing jaunt into Manhattan. Imagine the courage of a Vietnamese man, confined to a wheelchair since a medical accident in his mid teens, taking the bus to the train, negotiating the cavernous subway corridors of midtown, visiting the Empire State Building on his own. The next day I drove Binh into Manhattan, down through Harlem, alongside Central Park, to the Metropolitan Museum, which made access so easy from the garage. We found our way to the Van Goghs, where, by sheer luck, a docent was giving a lecture on, as I recall, The Flowering Orchard. I looked at Binh in his wheelchair and have never seen a more beatific smile in my life. “This is why I came here,” he said. Binh flew home to Hoi An, to resume his work. Whenever my friends are sight-seeing in Vietnam, I try to steer then to Hoi An. Last year Reaching Out was again judged one of the best small businesses in Hoi An. I just heard the other day – Binh and Quyen are expecting another child in May. * * * My other friend, Qui Tran, runs the family restaurant, Mai Lee, in a shopping center right near the Brentwood stop on the MetroLink rail line in St. Louis. When I am out in St. Louis pushing my Stan Musial biography, my buddy Tom Schwarz and I stop at Mai Lee for banh and spring rolls. Qui’s parents, Sau and Lee Tran, made their exodus from Vietnam, arriving in St. Louis in 1980. At first, Lee Tran worked in a Chinese restaurant but in 1985 she figured a way to sell her national dishes in her own place. Mai Lee now bustles at lunch and dinner, with the entire Tran family trying to keep pace with the crowds. “The new Mai Lee was worth the wait, believe us. And a weekend night crowd showed a superb mix of adults and children, grandparents and grandchildren, all ages and colors and sizes, and speaking many languages. A joyous experience,” wrote Joe Pollack and Ann Lemons Pollack in their popular dining review, St. Louis Eats and Drinks. It’s not hard to notice Qui. He’s the one with huge tattoos on huge muscles, bristling with confidence. The next generation. The American dream. I call him “my Vietnamese soul brother.” I doubt my two friends will ever meet, but they are linked in my heart. The word Vietnam evokes all kinds of images in the United States; when I hear the name these days, I think of beautiful scarves, succulent dishes, brains and muscles and courage. Happy Tet. |

Categories

All

|