|

It’s too hot to go out in Southwest France, report my cousin Jen and her husband Sam. Bulletin: Wildfires in Nouvelle Aquitaine and Gironde, Meanwhile, London was bracing for 104-degrees Fahrenheit – which would set a record. Back in the southwest corner of Virginia, they are still digging out after the aptly-named Dismal River suffered a flash flood last week. I know that portion of Virginia, from my days on the coal beat. Decades of strip-mining – lopping off the tops of mountains to get at the coal – have destroyed the watersheds of Appalachia. (I wrote a book called “One Sunset a Week,” about a miner’s family in adjacent Russell County. Every time the heavens erupted, the rains washed down detritus from strip-mining, known as “red dog.” That was 1974.) If only the governors and senators of Appalachia knew about this. Perhaps they might do something. The prototypical politician from Appalachia is Joe Manchin of West Virginia. He must know the ultimate flood is coming because he’s fitted himself out with a yacht, anchored outside Washington. When the Potomac rises, Commodore Manchin is going to float safely downstream – but to where? The Commodore has been busy. Last week, he slipped up behind the helpless ancient figure of Mother Nature and whacked her with a coal shovel and stole her pocketbook. He did it by voting against the tax bill that would have at least recognized the danger of rising temperatures, and the role of fossil fuel, not only all around the world but in his home state of West Virginia. His Inner Republican said he was being a guard dog for fiscal sanity, blah-blah-blah, but we know better. We know that decisions that affect the future of world ecology are made by the (white) (old) men who are either rich or wannabes. The Commodore is not only a scientific authority but also a coal baron, via his family business. It’s in trust, the Commodore tells us. He knows nothing – just like it was a shock to him that his daughter, Heather Bresch, presided over a drug company, Mylan, when the price of EpiPens – used to treat allergic reactions -- soared to $600 a shot. This was a shock to the Commodore. These kids today never tell their parents anything. Maybe the flood on the Dismal River in neighboring Southwest Virginia was a shock to the Commodore. Maybe the flood in Yellowstone National Park was a shock to the Commodore. Maybe the heat wave in far-off Europe would be a shock to the Commodore, if he heard of it. But the Commodore doesn’t have time to monitor events in such distant places. He just wants to balance the books, like a good Republican, although he is nominally a Democrat, and make sure energy moguls continue to make an honest buck, so they can all afford yachts to escape the cataclysm, so they can float off to some safe place, like maybe the Marshall Islands. Oh, wait. The Marshall Islands are going under, day by day. But don’t tell Commodore Manchin. He is heroically standing up for his constituency – energy barons, coal-mine operators. He’s a man of the people. A few of them. * * * I seem to be writing a lot about Commodore Manchin these days:: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/write-about-west-virginia-she-said https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/watching-manchin-thinking-about-the-the-sopranos  Borrowed from that great asset, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news Borrowed from that great asset, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news (Laura Vecsey is a terrific news reporter; she proved it in two capitals of major states. She once almost bought a bit of land in a scenic portion of northern West Virginia that George Washington had surveyed. The other day Laura offered some friendly advice to her father, who was thinking about writing about the baseball post-season: “You know West Virginia; write about that.” So here goes.)

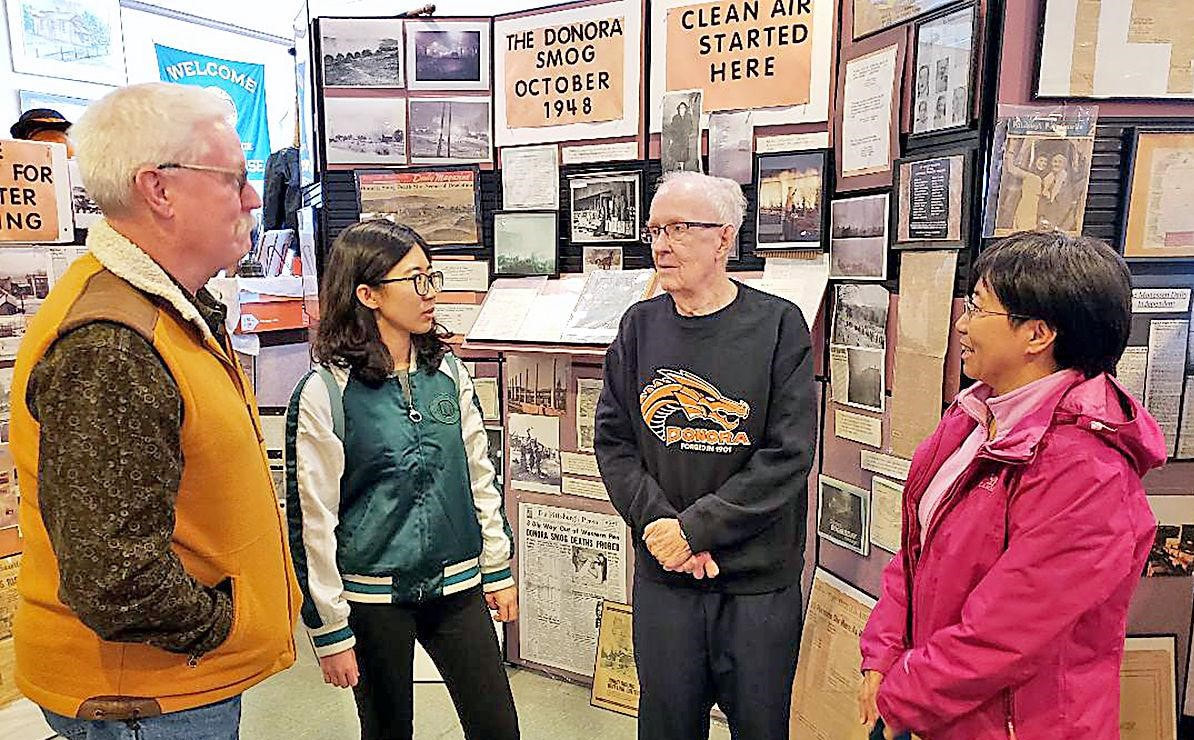

Joe Manchin was not in the spotlight when I was covering Appalachia in the early 70s. The governor of West Virginia back then was Arch A. Moore, who later did 32 months for campaign corruption. Manchin later became governor and is now a senator. Nominally a Democrat, he is doing his best to blow up bills that would protect the ecology and the people. He says his stance has nothing to do with the energy stock he divested. “It’s in a blind trust,” he often says. The governor now is Jim Justice, allegedly the richest man in the state. Some governors might be concerned about the water supply or the bleak future of the coal industry, but Jim Justice spends much of his psychic energy coaching the girls’ basketball team in East Greenbrier, W.Va., far from the capital of Charleston. He also wants to coach the boys’ team in East Greenbrier, but school officials are thwarting that little whim of his. Stay tuned. * * * West Virginia is not all grim coal camps and refuse from hilltop strip mining; the coal seams run out below the northernmost sector. One of my best friends recently spent a long weekend with three of her long-time girl friends in a remote cabin in the woods – had a great time, even though the fall colors had not yet arrived. She talks with great affection of her first couple of years in a West Virginia college. * * * The reason I love old-timey country music is from a few summers as a kid, spent in upstate New York, where you could tune in Kitty Wells, Hank Williams, the Carter family – clear as a bell, through the mountains, straight from WWVA in Wheeling. * * * One of my first trips to coal country was to report on Dr. Donald L. Rasmussen, who carried around slides of dead miners’ lungs – ravaged from years of work underground, inhaling coal dust. Some coal-company doctors used to tell miners that coal dust would cure the common cold, but. Dr Rasmussen displayed the grisly slides at public hearings or outside the headquarters of coal companies. * * * I also got to meet a member of the House of Representatives who cared – Ken Hechler, a World War Two vet, a New Yorker, and a writer, who settled in West Virginia and became an advocate of the miners, the poor, and ran for office – living to be 102. Hechler had a protégé, Arnold Ray Miller, a working miner who had absorbed the inequities of the business. In 1972, Miller – backed up by volunteers, those dreaded out-of-state college students, ran for president of the corrupt United Mine Workers. I traveled around with Miller’s cadre during the campaign; after the 1970 murder of the Yablonski family in western Pennsylvania, the campaign was under close protection – insurgent watchmen outside hotel rooms, everybody armed. Miller won the election in 1972, but nothing much improved. * * * In March of 1972, I rushed from Kentucky to West Virginia to cover the flooding of a valley, when a coal-mine refuse pond gave way in heavy rain, killing 125 people alongside Buffalo Creek, early on a Saturday morning. I interviewed next-of-kin and neighbors and learned that the company had sent a worker named Steve to bulldoze more earth onto the failing dam, high in the hills. That is to say, the company knew the danger but did not bother to warn the families downstream. My reporting helped inform a successful class-action suit, that did not bring back the dead. * * * The coal-mine carnage and the current conflict of interest by public servants would have been no surprise to one of the greatest figures in West Virginia history-- Mother Jones. Born in Cork, Ireland (home of strong women, I believe) Mary Jones left the potato famine for Toronto, lost her husband and four children, and became an advocate of organized labor in the U.S. – particularly West Virginia. (She often praised the valor of Black laborers.) To know more about her: https://history.hanover.edu/courses/excerpts/336jones.html https://www.biography.com/activist/mother-jones The people of West Virginia deserve better. In 2016, they voted, 68 to 26 per cent for Donald Trump, who soon abolished as many pro-ecology bills as he could. Many miners understand theirs is a dying industry. But guess who bellied up to Trump in the swarm after one of Trump’s first speeches? None other than Blind-Trust Manchin. Where is Mother Jones when West Virginia needs her?  Dr. Charles Stacey, black shirt, gives a tour to two Chinese students and their college prof. Dr. Charles Stacey, black shirt, gives a tour to two Chinese students and their college prof. There’s a new TV series with Jeff Daniels playing a sheriff with tangled loyalties, in a faded steel town in the Mon Valley of Pennsylvania. As soon as I heard about it, I said, “Hey, wait, I know that place.” I came to know it, and root for it, in 2009-10, when I was working on the biography of Stan Musial, the great star of the St. Louis Cardinals, who grew up where the Monongahela River twists between the hills and fading towns and dormant steel mills. Humankind has since screwed up a lot more places, probably irrevocably. The Mon Valley was a signpost, a warning, of what we were doing. After the steel mills and coal mines were played out, some people were still living in, essentially, the ruins. That is the site of the new series, “American Rust,” from the book of the same name, by Philipp Meyer, which had just come out in 2009, when I began my research on Musial and his roots. Musial’s dad had migrated from Poland to work in the mills, joined by immigrants from Europe and Africa and the east coast. I read that the new series was filmed in studios in modern high-tech Pittsburgh, but some of the exteriors were shot in Monessen, just across the Stan Musial Bridge from Donora, where Musial grew up. He played basketball and baseball for Donora High, but his first baseball tryout was conducted in Monessen, where the St. Louis Cardinals had one of their many farm teams. From what I read, Daniels’ TV town is as gray as the smoke-filled skies from the 1948 Halloween killer smoke cloud, known as “The Donora Smog.” (Stan Musial’s dad, Lukasz, breathed too much of that smog, trapped under an inversion on that October night, and was dead two months later – too much American rust in his lungs.) Musial was no longer capable of giving interviews when I worked on the book – he would die in 2013 -- but other people took me around the valley. One of my tour guides was a local hero named Bimbo Cecconi, a former Pitt football star and coach, now living up near Pittsburgh, who walked the hills of Donora and told me about the athletes from his hometown – Deacon Dan Towler of the Los Angeles Rams and Arnold Galiffa who played at West Point, and three generations of ball-playing Griffeys – Buddy and Ken and Ken Junior. Bimbo escorted me to the Donora Public Library where Donnis Headley became a helpful source. When the Donora microfilm machine was out of commission, she directed me across the river to the Monessen library, where I read old clips about Musial and the two towns. My other guide was Dr. Charles Stacey, who had been the superintendent of schools, and still lives on the main street, McKean Ave. Dr. Stacey gave me a black T-shirt with the legend Donora Smog Museum, which he had opened in the shell of a former Chinese restaurant. Dr. Stacey was also a mentor to Reggie B. Walton, once a football star on the verge of gang trouble, who willed himself to a historically Black college and a federal judgeship in Washington, D.C. Judge Walton is a Republican who has delivered decisive and apolitical rulings. As I walked around with Dr. Stacey, I expressed interest in talking to Judge Walton A week later, my home phone rang and a man said, “This is Reggie Walton….” He said Charles Stacey had asked him to call me – one of the honors of my working life. I wonder if this new series will take note of this accomplished judge who came out of the American Rust. I learned other things from my days in the Mon Valley. -- “Monongahela” is of Native American origin, meaning “river with the sliding banks” or “high banks that break off and fall down.” --A young surveyor from Virginia, George Washington, was an aide to Gen. Edwin Braddock who was killed in action further downstream in the French and Indian War in 1755. -- The names of Monessen and Donora are both amalgamations. --- Monessen’s name is a salute to the German emigrées, from the industrial town of Essen. -- Donora was named by industrialist Andrew Mellon of Pittsburgh, who built a new steel town at the end of a freight line. Mellon honored W.H, Donner, an executive who had made a lot of money for him, and also honored Mellon’s young wife, whom he had brought over from Europe -- Nora McMullen. The Mellon marriage did not last long but the odd mixture of names survives in a gritty town with memories. I came away from my visits to Donora and Monessen with the same rooting interest I have for Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, further down the Appalachian chain, where I used to work. I cringe when I hear about the rampant use of opioids, the crime statistics, the dropouts, in Appalachia, and I gather that is the backdrop to this new series. I’ve seen a few of Jeff Daniels’ interviews on TV, and he always stresses that while he works in Hollywood or Broadway, he always goes home, to Michigan – “Fly-Over Country,” I heard him say, using the ironic term midwestern people use for their part of the country. Maybe I’ll catch some of “American Rust” sometime; (I don’t have Showtime on my cable package.) Some of the reviews I’ve read are not ecstatic, but I wonder: is Appalachia just not sexy enough for Americans? After all, “The Sopranos,” in tense urban New Jersey, was the best TV series I have ever seen, and “The Wire” made people pay attention to inner-city Baltimore. I just hope the writers – and the viewers -- do right by the Mon Valley. ### Tom T Hall passed on Friday, He was a country songwriter who informed my work, telling stories about people. He observed every-day life, regular people, and made them real, with a large dollop of insight and sympathy and wit. I read the lovely obituary in the Sunday NYT by Bill Friskics-Warren and I tried to remember when I first heard Tom T Hall. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/21/arts/music/tom-t-hall-country-musics-storyteller-is-dead-at-85.html I think it was after I had been one of the first reporters on the scene for the terrible mine explosion in Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. I came back many times, met a lot of survivors – “the widders,” as they say. Turned out, Tom T. Hall was there soon after. He and a buddy drove a pickup from his home in Olive Hill, Ky., not far from the coal region, and he observed with a storyteller’s eye, including the sheriff and the undertaker whom I had met. Maybe he had read my stories, maybe not. Didn’t matter. He put it to music, got it perfect. (The “pretty lady from the Grand Ole Opry” is Loretta Lynn, who had come off the road to play a charity concert in Louisville in 1971, for the survivors. That’s how I got to know Loretta, and later helped her write her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.”) In the next years, I collected cassettes of Tom T Hall’s best albums and songs and would play them as I drove around Appalachia. . Some of his best songs were about lost or unrequited love: “Tulsa Telephone Book” -- Readin' that Tulsa telephone book, can drive a guy insane Especially if that girl you're lookin' for has no last name. “The Little Lady Preacher” -- (A picker remembers the gospel singer he backed up every Sunday morning: “She’d punctuate the prophecies with movements of her hips.”) We never met, but I took my young family to see him in New York in the mid-70s. I learned that he had settled in the lush outskirts of Nashville with his wife, Miss Dixie, herself a fixture in Music City, who passed a few years back. I owe Tom T Hall a great debt because he helped me recognize the best parts of people, as flawed as we all are. Only he put it to music and he sang it. In honor of Tom T Hall – a requiem for the older friend who taught him to pick, and other stuff.  Michael Apted, young director Michael Apted, young director (I was gearing up to write something about my despicable ex-neighbor from Queens, who is trying to take the country down with him. Then I read the obits of two people who enriched my life, in several senses of the word, and realized I need to pay homage to Michael Apted and Tommy Lasorda.) * * * I was afraid of what Hollywood would do with Loretta Lynn’s book, and her life, and her roots in Eastern Kentucky. Having been the Times’ Appalachian correspondent, I was blessed to get to know her and be asked to write her autobiography, and have her tell me great stories that made the book “Coal Miner’s Daughter” so easy to put together. Then the book was marketed to Hollywood. From a vast distance, I heard rumors that this producer or that director wanted to put out a steamy version, a Beverly Hillbillies knockiff, of her colorful life. But then, way out of the loop, I heard that the Hollywood gods had lined up producer Bernard Schwartz….and screenwriter Tom Rickman….and British director Michael Apted. I exaggerate sometimes that when I say that I was invited to an early private screening in Manhattan and brought a fake mustache and a wig and a raincoat I could put over my head like gangsters do when they are arraigned. I did fear the worst. Then the movie began in the little screening room and I saw Levon Helm, as Loretta’s daddy, coal dust all over his face and hands, coming home from the mine and being met by his daughter, played by Sissy Spacek, and instead of goofus cartoon figures they were tender father and daughter, giving thanks that he had survived another shift underground. I could breathe. No disguises necessary. “The good guys won,” Rickman told me later. Michael Apted, best known for his “Up” documentaries, was a principal good guy. He has died at 79. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/movies/michael-apted-dead.html I got to meet Apted a few months later at the “grand opening” in Nashville, where my wife and I were treated like one of the gang. Levon, Sissy and Loretta (if I may call them by their first names) gave an impromptu concert at the hotel, and the next day “we” took a chartered bus up to Louisville. I chatted with Apted for a few minutes and told him how much I loved the movie, how fair it was to the region and how it lived up to what we had tried to do with her book. I still remember one sentence: “I am no stranger to the coalfields.” Later, I looked it up and saw he was born in posh Aylesbury and grew up in London, but the point was, Michael Apted was a serious film-maker who traveled and learned and listened. For a more distinct Appalachian feel, he incorporated some locals into the movie, just as Robert Altman did in the movie “Nashville.” I never met Apted again, but I am eternally gratefully to him and Schwartz and Rickman and the talented performers. * * * I knew Tom Lasorda better. I met him in the early 80s when he was already a celebrity manager with his monologues about “bleeding Dodger-blue blood.” He made it his point to know the New York sports columnists and including us as bit actors in his own personal production..

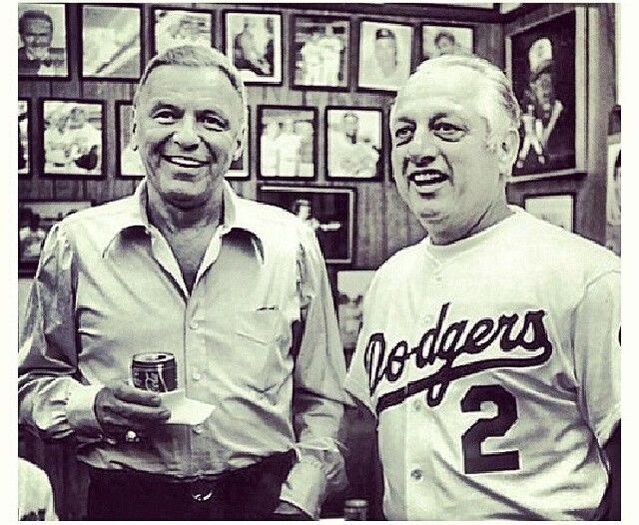

One time he told me that “Frank” had been at the game the night before. I guess I looked blank and he sneered at me and shouted, “Frank! Frank! Frank Sinatra!” Wherever he was, Lasorda’s clubhouse office might be home to show-biz or restaurant types, plus Mike Piazza’s father, Vince, Lasorda’s childhood pal. One time, in a big game in LA, the Dodgers had a lead in the late innings and there was a commotion in the dugout as Jay Johnstone ran out to right field and waved off some directive. Later we asked Lasorda what happened, and he said he tried to send Rick Monday out to play defense – a normal tactic -- but Johnstone had run past him, saying, “F--- you, Tommy, I’m not coming out!” Lasorda told it -- laughing, proud of Johnstone’s stand – particularly since it had not cost the Dodgers. I was working on a book with Bob Welch, the pitcher and my late friend, about his being one of the first athletes to go through a rehab center for alcoholism. I knew Lasorda had made a brief visit to the center during Bob's family week, and I wanted his recollections, but Lasorda was evasive. Finally, on the road, he agreed to talk to me in his hotel suite, blustering, raising his voice, as if somebody were listening in the next room. “He’s not an alcoholic!” Lasorda shouted. “He can take a drink or two! He just has to control it!” – totally against what recovering addicts know to be true. I will give Lasorda credit for giving me the time…and his point of view. Whenever we met, he always said hello. Whatever his personal life was like, he loved wearing Dodger Blue. In his bombastic showboat way, he incorporated peripheral types, like a New York sports columnist, into his world, and he made us enjoy our little part of it. * * * Richard Goldstein and Tyler Kepner have told many great tales of Lasorda’s life: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dodgers.html?searchResultPosition=1 Just in case you missed it, there is a marvelous series on PBS this week called “Country Music.”

I watched the first two-hour installment Sunday night instead of the Mets and Dodgers, which says a lot. (Okay, I peeked at the score periodically on my cellphone.) The educator Jacques Barzun is remembered for writing, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball….” I would add country music to that observation. It has been there, the rhythms and words of the complicated American heart – particularly by the expanded definition and parameters submitted by Ken Burns, the producer of the 16-hour series. “Country Music” is lavishly arranged for the next full week on PBS (two hours, repeated the next two hours, at least on New York’s Channel 13.) Burns and Dayton Duncan, the writer, have expanded the definition of country music way beyond the sequins-and-overalls very-white image to a more inclusive version that pays homage to black/gospel/race/soul music. Burns and Duncan consciously blur the lines, showing copious footage of black churches, black performers and black fans, sometimes mingling with whites far more openly than I would have imagined. My time as Appalachian correspondent for the Times, later helping Loretta Lynn and Barbara Mandrell write their books, gave me marvelous access from the wings of the Grand Ol’ Opry and on the buses and concerts and other good stuff. I did not see much of a black audience, but Burns and Duncan have the footage and sound tracks to include blacks – plus, Elvis Presley, bless his dead heart, always acknowledged his overt inspirations from southern soul music. But country music is, ultimately, built on the strains and the sentiments straight from the British Isles (and the complicated heritages there.) I have always maintained that when the brilliant Dolly Parton opens her sensual mouth and lets the thoughts and the music flow, she is in touch with hardy people who emerged from the hills of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, who had the courage to get on a boat and sail across the ocean – often to escape back into the hills of that new world. Dolly, for all her glitz, is a medium. The women – Kathy Mattea, Dolly Parton, Rosanne Cash and Rhiannon Giddens, lead singer of the old-timey Carolina Chocolate Drops – carry the first segment. The series opens with Mattea (you should know her work) describing her arrival in Nashville from West Virginia, at 17, too young to perform, but able to work as a guide in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Lovingly, she points at the Thomas Hart Benton painting, “The Sources of Country Music,” as compelling the best museum docent you ever heard. The first segment, and I can only assume the entire series, has the same high level. This is serious stuff about America, about us. What did I learn? I had no idea Jimmie Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” was as widely popular as he was from 1927 to 1933, when he was cut down by equal parts hard living and tuberculosis. I thought he was more of a regional phenomenon. Rodgers lived the music he sang, and sold tons of records (for Joe Biden’s record player, and the old Veep is not alone.) Rodgers made his last record in New York City, propped up by shots of whiskey between takes. There is a poignant photo of Rodgers on a lounge at Coney Island, enjoying the sun, a day or two before he died, at 35. Then came the special train ride home, the old railroad hand heading back to Mississippi. The documentary should have ended with the Iris DeMent version of the Greg Brown song, “The Train Carrying Jimmie Rodgers Home,” with DeMent’s voice a mournful train whistle cutting through the southern night. But that’s just me, an Iris groupie. The first segment includes DeFord Bailey, a black harmonica player, an early staple on the Opry, and Ralph Peer, who turned country music into a lucrative industry, and the Carter family (I got to see Mother Maybelle perform in her later years), plus commentary from Charlie Pride and Wynton Marsalis, as well as Merle Haggard and Mel Tillis, both interviewed before their deaths, in the past few years. The second installment, Monday night, will focus on the Depression, using the Stephen Foster dirge, “Hard Times,” for its title. The Mets will be playing in Colorado, trying to hold on, but I will be watching “Country Music.” That about says it. It took a lovely post by a friend to remind me that Mardi Gras is about to morph into Ash Wednesday.

Bill Lucey, a writer and editor in Cleveland, puts out a thoughtful website about (a) baseball, (b) journalism, and (c) life itself. His post today is about how he should observe Lent this year. His examination of his faith should be read on its own, not in my paraphrasing: https://www.dailynewsgems.com/2019/03/the-meaning-of-giving-up-for-lent.html Lucey's article prompted me to recall Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday from my own perspective, having been raised (and raised well) as a Roman Catholic. I know my two sisters and their families will be observing Lent. (We took two close relatives to our beloved Mama’s in Corona a few years back –during Lent -- and they had to pass up some of the glories of deli and pastry. Oy. That is faith.) Today’s post by my colleague prompted two memories: 1. As the oldest of five, I was fortunate to walk to church on some weekdays with my Irish-born grandmother, always in black. Sometimes she would take me to a luncheonette on Jamaica Ave., for breakfast after church – but maybe not during Lent. I don’t remember. (Kids, ask questions of your grandparents…and your parents. Get their views, their histories.) 2. My most vivid memory of Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday is from 1971, when I was a news reporter for the NYT, based in Louisville. I had just covered my first coal-mine disaster, in Hyden, Ky., and was still reporting on it. On Feb. 23, however, I was in central Tennessee, covering a story on an army base. I had no clue about Mardi Gras until I had to wake up before dawn to drive across to a hearing in Eastern Kentucky. Barreling due east on the interstate, I messed with the radio dial (much more fun in the pre-digital age) and found a lively station – WWL, New Orleans, 50,000-watts. This post began as a memory of Lent, a spiritual journey, but somehow it is turning into a tribute to the great clear-channel stations of North America – the ones that would keep you going on cross-country drives. (Grand Ole Opry on Long Island on Saturday nights; one Phillies-Cardinals thriller all the way out to Chicago.) https://www.radiodiscussions.com/showthread.php?617480-50-000-Watt-Stations-on-North-American-Clear-Channel-Frequencies This time, pre-dawn on Feb. 24, 1971, I listened to the overnight DJ on WWL raving about Mardi Gras, which was slowly winding down on the littered and sodden streets of New Orleans. He talked about the beads, the drinks, the costumes, the food, the pretty women, the people leaning off their elegant balconies in the French Quarter, shouting and personifying the slogan: “Laissez les Bon Temps Rouler!” And there I was, in the dark, on I-40, heading to a hearing about poverty and neglect in Appalachia, taking in reports of the last bursts of sensuality in New Orleans. Mardi Gras turning into Ash Wednesday, mile by mile. That was Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday, 1971. Now, stirred by Bill Lucey in Cleveland, I have to figure some way to honor Lent. Thanks, man. Outside, the storms – political and meteorological – were raging. Inside there was a winter concert, by students and, later, enthusiastic alums.

How sweet it was, to find shelter from all storms, to hear young people play and sing, with considerable skill. Our youngest grandchild was in one of the ensembles, but honestly the quality of the music and the spirit of the young people would have been an attraction by itself. This was Thursday evening at Schreiber High School in Port Washington, Long Island, which, as much as it changes, retains its home-town feel, on a peninsula, with a train line terminating there, and a real downtown -- 45 minutes by rail from Penn Station. The superb arts department produced one concert Wednesday and another on Thursday – an orchestra, a band, a choir, and then an ensemble for the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” A young woman gave a haunting flute solo; a young man led one section with a strong first violin; a young man played a specialty instrument that evoked the swirling of the sea. I was particularly captivated by the choir, having had the privilege of singing in Mrs. Gollobin’s chorus at Jamaica High School in the mid-‘50’s and admiring the choir members. I watched the faces of these young people as they put their hearts into “Rock of Ages,” and, I will confess, I remembered our chorus harmony from 1954-56, and I softly hummed to myself. I thought of the choir stars from Jamaica High – an alto who taught music at a university in Texas for many decades, and our two lead sopranos who came back for reunions, still beautiful and active well into their 70s. And then there was Eddie Lewin, star soccer halfback and lead in our musicals. (Lotte Lenya came to our performance of her late husband Kurt Weill’s operetta, “Down in the Valley,” with Lewin playing the lead role.) In later years, Eddie took a pause in his medical career to fulfill his dream of touring with “Fiddler on the Roof.” I thought about our choir and chorus while watching the young people of Port Washington as they performed so brilliantly in their own time. At the end, the leaders honored the tradition by calling all alumni of the music department to join them in Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Dozens of recent graduates filled up the sides of the auditorium. They were asked to call out their graduation classes – 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 – and somebody said, “1976!” That was Jonathan Pickow, a well-known musician from our town, the son of Jean Ritchie, one of the great traditional folk singers and historians from her native Eastern Kentucky. (Ritchie Jean and her husband George Pickow – now both passed – lived high on a hillside in our town. First time I heard Ritchie was at Ballard High in Louisville, when we lived there, around 1971-2. She reassured Kentuckians that the steep hill on glacial Long Island made her feel she was still in Viper, Perry County. Jon has toured with Harry Belafonte, the Norman Luboff Choir and other choirs, has performed with Oscar Brand, Judy Collins, Theo Bikel, Odetta, Josh White, Jr., Tovah Feldsuh and my pal, Christine Lavin. And there he was, amidst musicians more than 40 years younger than him, talking respectfully of having been part of music programs at Schreiber High in Port Washington, back in the day. Music is classical; it provides shelter in all storms. * * * PS: Jean Ritchie wrote the classic protest song, "Black Waters," about strip-mining, which obviously the tone-deaf Mitch McConnell from Louisville has never heard. https://politicaltunes.wordpress.com/2014/01/31/jean-ritchie-black-waters/ https://www.nytimes.com/1984/04/16/arts/weill-s-opera-down-in-the-valley.html http://www.jonpickow.com/bio/ https://www.ket.org/education/resources/mountain-born-jean-ritchie-story/ https://www.allmusic.com/artist/the-cleftones-mn0000073914/biography The other night, the conscientious Chris Hayes did a documentary from West Virginia, with the impassioned Sen. Bernie Sanders.

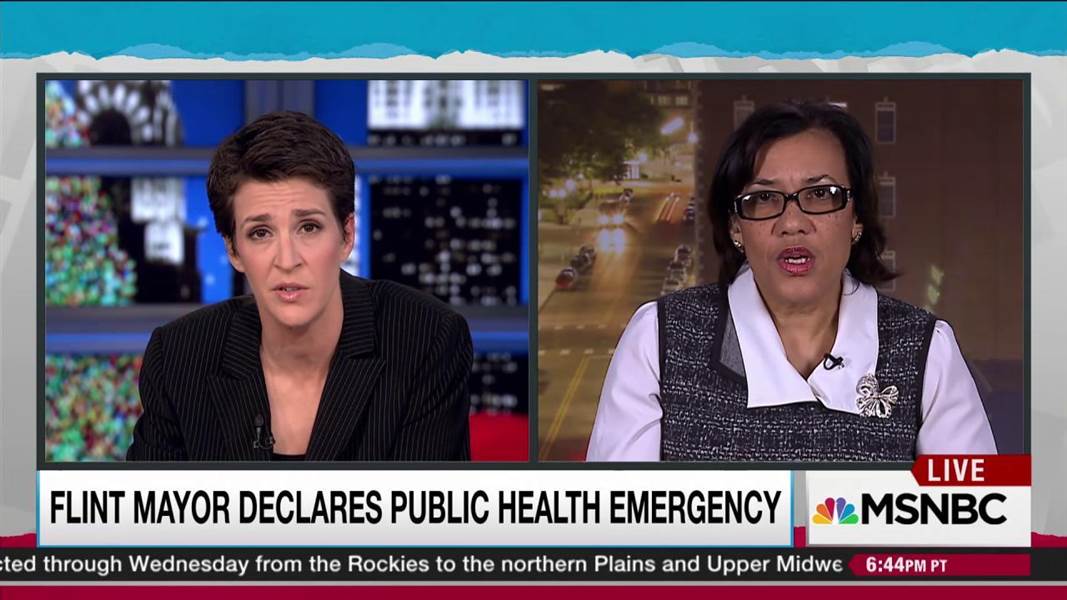

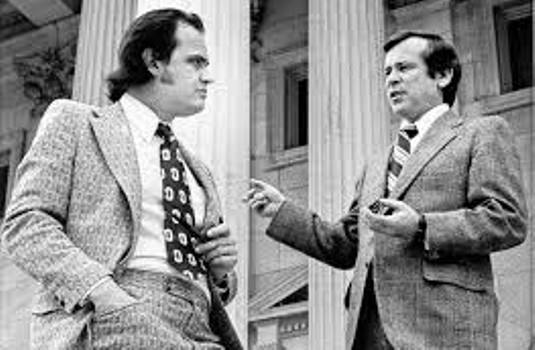

I couldn’t watch. The state already voted for the poseur, Donald Trump, last November by roughly 68 to 26 per cent over Hillary Clinton. It’s all so familiar. Living in Kentucky, I covered Appalachia for the Times from 1970 through 1972 and remained in close touch for many years afterward. I saw bodies fished out of Buffalo Creek after an earthen coal dam gave way. I saw the crusading Doc Rasmussen going to hearings with an autopsy slide demonstrating Black Lung. I covered a few coal-mine disasters and the Harlan strike of 1974, so grippingly captured by Barbara Kopple. So long ago. So courant. The only thing that has changed is that we know more. Technology has gotten better – and worse. Coal companies can push more detritus downhill into the streams and gardens of their own people and scientists can measure the damage to air and water and lungs more carefully. When I covered West Virginia, Rep. Ken Hechler was the Bernie of his day, speaking out against corruption and pollution. (Hechler passed recently at 102.) A miner named Arnold Ray Miller tromped around to speak against corruption in his union – and was elected president in 1972. There was often hope of change, of throwing out the rascals and the big-city corporations, but decades have gone by, and good people still want to work, and young people have no hope and are resorting to killer opioids pushed on them by the same kind of doctors who said coal dust was good for the common cold. Every reliable study says there is no future, no justification, for digging and burning coal, yet frauds like Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and Big Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who calls himself a Democrat, bow down to their masters from Big Coal. It is pathetic. The decency and the religion and the patriotism of people from West-by-God-Virginia make them susceptible to all kinds of drugs – crooked politicians, phony prophets of economic success. Hillary Clinton, in her own artless way, told people that coal mines would be shut down. So they voted against her. Of course, Sanders had won the Democratic primary in West Virginia, proving that people of that state are terribly bifurcated, at their own expense. One of the first things Trump did to Appalachia was to remove barriers to dumping waste into the valleys where people live. And Big Joe shook Trump’s hand after his first speech to Congress. My wife and daughter Laura (who used to cover rascals in Pennsylvania) told me the MSNBC program was terrific. Now it seems people in McDowell County are speaking up for health care and even Big Joe Manchin is getting the message that you can sell out your own state just so long. God bless Bernie Sanders and Chris Hayes and West Virginia, but I just couldn’t watch. Thousands of children and adults have been poisoned in Flint, Mich. On Wednesday night in Flint, Rachel Maddow – who has served as a national conscience in this latest tragedy mixing politics and pollution – held a “town-hall” meeting on MSNBC. The meeting provided information and a bit of catharsis for people in Flint -- but no detectable action or shame from the dim-bulb state government that has occupied poor towns in Michigan in recent years. However, Flint is not the only place where poisons have been let loose. More below. This horror in Flint has been coming for years, since Gov. Rick Snyder began appointing unelected “managers” to run some Michigan towns, many of them with large black populations. It looked like the bad old days of South Africa. To save a few bucks, Snyder’s brain trust chose to use water from a polluted river rather than Lake Huron. None of Snyder’s “experts” knew enough to install filters, so lead began showing up in the water – and in children’s bodies. Lately the governor has been standing around, looking a bit stricken, as people passed out donated water bottles, hardly a solution to the health crisis. On Wednesday night we learned that it might cost over $10,000 per house to replace the poisoned lead pipes. No work has started. The state government is now in the position of needing help from a federal government that it has vilified as the enemy -- kind of where we are in this country these days. Maddow has been shining a light on some states with Tea Party and Koch Brother types – North Carolina, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Michigan and Virginia. She reported on Bob McDonnell, then the governor of Virginia, for his fetish for highly personal medical scans of women, labeling him “Governor Ultrasound.” McDonnell and his estranged wife are now appealing prison sentences for corruption while Maddow has moved on to Flint, which badly needed a friend. America is good on polluting itself. The New York Times, in the Jan. 10 issue of its Magazine, ran an absolutely riveting article about how DuPont dumped its refuse in the water table of northern West Virginia for many years. A highly responsible mainstream Cincinnati law firm allowed one of its corporate lawyers to take up – and win -- a pollution case. But with pollution, there are no victories. I recently talked to Mike Glasser, a friend of a friend, who is taking chemo for cancer he believes was incurred while mixing chemicals amounting to Agent Orange. But it was not in Vietnam, where we dumped it willy-nilly. It was at Chanute Air Force Base in eastern Illinois, long closed, with people and animals and lakes and land showing signs of chemical damage. One young reporter, Bob Bajek, took up the issue for a local weekly, and managed to get a highly detailed story published pointing to chemicals used at Chanute more than 40 years ago. Bajek doesn’t work there anymore. One of his superiors said he stirred up trouble, writing things people didn’t like to read. * * * Here are two links by Bob Bajek: His reporting on the pollution: (click link below:) _ and the response to his work: (click link:) _ * * * None of this is new. May I recommend this version of “Black Waters,” performed by Kathy Mattea, from South Charleston, W. Va., as courant as when the great Jean Ritchie of Viper, Ky., wrote it in 1971. Mattea's prelude is worth hearing. Black waters are now flowing in Flint. Fred Thompson’s obituary reminded me of another time and place, when fewer public figures made me feel, well, I think the word is icky. In the very early ‘70’s, I was a New York Times Appalachian correspondent based in Louisville. There were giants in those days, who believed in government. Some of them were Republicans. I got to write about Sen. John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, Mayor Richard Lugar of Indianapolis and a young United States Attorney from Western Pennsylvania, Richard Thornburgh, who gave me a private seminar in jury selection that informs me to this day. One lovely fall day, I took a ride around Nashville with Sen. Howard Baker, who was running for re-election. He brought along his campaign manager, tall and droll, Fred Thompson. I don’t remember a word. My story included Baker’s Democratic opponent saying Baker was too liberal toward the antibusing movement. I only remember good conversations in the car and Fred Thompson’s pipe. For a lefty from New York, I was not at all surprised to see things from their perspective, and to enjoy their company. The Watergate break-in had taken place three months earlier. It was not mentioned in my story. None of us had any way of knowing Baker would be a major figure in the hearings, and that Thompson would become famous for whispering to Baker, as one of his chief assistants. I was not the slightest bit surprised when Baker was seen as a stalwart, honest man who examined the evidence against President Nixon. I followed their careers, as Thompson became an actor – well, he was always an actor – and a senator himself. Recently, I came across a story I had written in 1972, about possible legislation to limit strip mining – ripping coal from the surface of hilly Appalachia. The two proponents were Sen. Cooper from Kentucky (who was about to retire) and Sen, Baker from Tennessee, both Republicans, from coal states. I thought about the way current senators grovel in front of coal -- Joe Manchin of West Virginia (a nominal Democrat who sometimes seems like a nice guy) and Mitch McConnell of Kentucky (who does not, ever.) In the year of Trump and Carson and the nebbish Bush and the twerp from Florida I call El Joven, I remember a sunny day driving around Nashville with Howard Baker and Fred Thompson – and not feeling like I needed a shower afterward. What has happened? They were heading from Lexington to Chattanooga when the clouds lowered. When I spent a lot of time in the mountains, I loved to watch pockets of fog nestled in the hollows (pronounced "hollers.") Anjali noticed them, too. I would have posted the classic 1972 recording of "Rolling Fog" on the "Dobro" album by the Seldom Scene, with Mike Auldridge, but I couldn't seem to locate a single. So here is one of America's musical treasures (never mind the glitz), Dolly Parton, singing about East Tennessee. The year is full of fiftieth anniversaries, including the March on Washington and the terrible event coming up on Nov. 22.

Two other milestones are worth noting: the publication of a landmark book about Appalachia and the death of a landmark publisher. I got to meet Harry Caudill and Alicia Patterson, two strong-minded patricians. As a young sports reporter at Newsday on Long Island, I was aware of the publisher, with the tone of the country club and the vocabulary of a press room. She was descended from the newspaper family of McCormicks and Medills and Pattersons, and in 1939 she had been given a newspaper by her wealthy husband, Captain Harry F. Guggenheim. It was her toy, and she turned it into a great newspaper. You could hear her down the hall, conducting business with her editors, a presence -- jewelry glittering, glasses perched on her forehead. The boss. Miss P. I don’t claim to know what she did and said. I only know that all of us took energy from her. At Christmas parties, Stan Brooks – the same whirlwind reporting from the street for WINS radio today – used to don dress, glasses, stockings and high heels for a fantastic takeoff of Miss P, who loved it. You can read all about Alicia Patterson via her foundation: http://aliciapatterson.org/alicia-patterson The final praise for her is from Jack Mann, the irascible sports editor who gave me a career. Jack got himself fired in the summer of 1962 after a dispute with a managing editor while Miss P was out grouse-hunting or something. When she came back, she told Jack she could not countermand her editor. I never heard him badmouth her for that. A year later Miss P died during surgery for ulcers, at 56. The paper had glory years after her time, including the great run of New York Newsday, but it is now run by the Dolans. Some of us think it would never have slipped this way if Miss P had lived a few more decades. Harry Caudill’s voice reached the big cities, all the way from Whitesburg, Ky., where he was a lawyer. In 1963, he wrote a lament called Night Comes to the Cumberlands, about the colonization of Appalachia, where coal lay under the surface. His book made me care for Appalachia; seven years later I went to cover it for the New York Times. Things were about as bad as he said, but I was captivated by it. I got to meet Caudill, who goaded me to spend more time in the mountains. When A.M. Rosenthal, the great editor of the Times, was making a tour of the region in 1971, we had a nice lunch with the Caudills, who had the ear of the paper. The next summer Caudill called the home office to say an entire mountain had shed its coal slag, known as red dog, into a community. I was dispatched from vacation at Jones Beach to a bare-bones motel in Whitesburg, by which time a few families had raked the stuff out of their yards. Caudill saw disasters large and small, standing up to politicians who served the coal industry. He suffered from a war injury, and came down with Parkinson’s Disease, and committed suicide in 1990 at the age of 68, in his yard, facing Pine Mountain. http://www.kentucky.com/2012/12/23/2452306/chapter-5-harry-caudill-inspired.html By that time, I had written a book about a radical miner in southwest Virginia called, “One Sunset a Week.” Caudill’s book is still the most important book about Appalachia. Fifty years later. (Alicia Patterson, reading her paper; Harry Caudill tutoring a visitor, Robert F. Kennedy, who paid attention, who cared.) The 40th anniversary of Buffalo Creek kicked up all kinds of flashbacks.

One of them was a glint of sunlight on a wire, stretched across the valley. I did not see the glint; fortunately, the helicopter pilot did. The official total of dead from the flash flood in Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, on Feb. 26, 1972, was 125, but it almost became higher. The helicopter episode came when somebody in authority offered The New York Times a place on an Army helicopter that was doing reconnaissance in the long narrow valley. As a reporter, you always accept these offers. I had been in helicopters before, but they always had doors and stuff. This one, as I recall, had a chain or belt stretched across a portal. I was strapped into my seat, but my inner core had the sensation of dangling out. It was eerie enough, trying to adjust to pickup trucks lying in creek beds, mobile homes stretched across roadways, lowlands flattened as if by a giant bulldozer, and knots of rescue workers, poking in the flotsam at every bend of the river. Not much was moving. We were heading uphill, where the coal company had placed an earthen dam to catch all the water and junk from the mine. Suddenly, I heard the pilot mutter something as he made an evasive veer, straight up, as I recall. We came to understand that he had spotted an electric or telephone line stretched across the valley. Forty years later, I have no idea how close we came. All I remember is the mixture of gravity and fear in my stomach. Whenever I think of Buffalo Creek, that little episode comes to mind. * * * The pistol adventure happened a few days later, when the Times home office asked me to check for more earthen dams in the region. I caught up with Ken Murray from Tri-Cities, who remains one of the great photographers of Appalachia. Ken and I had met right after the mine blew up at Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. We both went to the first funeral -- the shot man who had been using outdoor explosives indoors, during weather when methane gas is at its most explosive. We became a unit on subsequent assignments, with Ken contributing far more than this city boy ever could. This was when I learned to rely upon all the great photographers I have worked with. Ken and I drove around, looking for likely topography that might harbor an earthen dam. We were halfway up a hillside when the company guards caught up with us, clearly trespassing. I won’t say they were aiming their pistols at us, but they let us see the pistols. Ken and I were well aware that in 1967, the Canadian filmmaker, Hugh O’Connor, had been blown away after walking onto somebody’s property in rural Kentucky while making a documentary. My fellow journalists always told me that story – I think, to get a rise out of me, but they were surely doing me a favor, too. (The only time I ever had a gun actually pointed at me was by a very nervous young trooper wielding a nasty-looking shotgun during a riot in Baton Rouge in that same era. The trooper told me to produce my identification and I talked him through the process of my rummaging around in my pockets, and was he all right with that? I still do that whenever an officer tells me to produce my wallet. Nothing like play-by-play to calm testy officers with weapons.) Anyway, the coal guards interrogated us, until their boss arrived. As it happened , Ken and I knew the man from an earlier story we had done. He shook his head and said he was very disappointed in us. Meanwhile, Ken whispered, “Let’s get down to the state road; that’s public property.” We started putting one foot after another, telling our story walking, until we reached the highway. I told the foreman I had made a terrible mistake and would never get lost like that again, and we drove off. Didn’t find any earthen dams that day. Just guessing they’re still up there, waiting for the next hundred-year-rain in a week or two. Buffalo Creek.

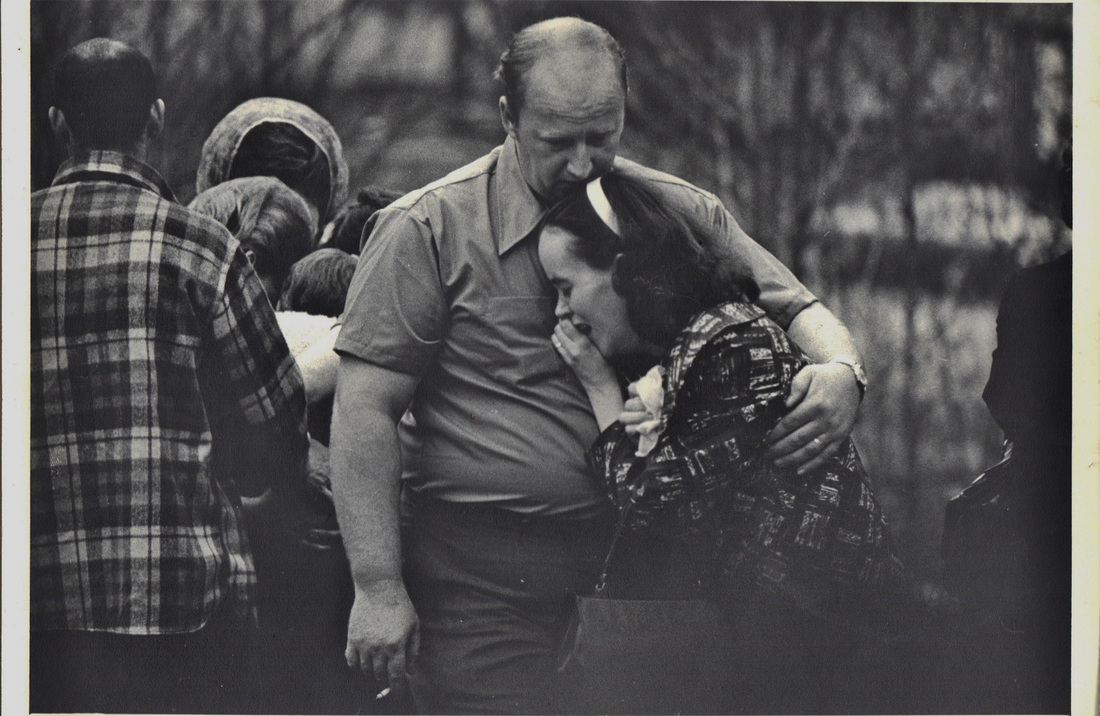

After 40 years, the name still haunts me. I think of people and homes and cars, scattered like toys, demolished by a capricious child. The morning of Feb. 26, 1972, looked pretty much like coastal Japan during the tsunami of 2011, except this destruction was man-made. The coal company had created an earthen dam near the top of the valley, to capture waste slag and water from the mine. Apparently, they never counted on a heavy rain. They called it a "hundred-year rain." I would hear that phrase every few months, somewhere. I was working in Kentucky as a national correspondent for The New York Times when I got the call. The dam had let loose near dawn on Saturday morning. By the time I drove across to West Virginia, the death toll was heading toward 125. I went to a shelter at the local school and found a man who had been up on the hill tending to his garden when the dam broke, and he watched the wall of water sweep his family away. This was my second coal disaster, after Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. My boss, the great reporter and editor, Gene Roberts, had prepared me for covering Appalachia by telling me that if you spoke quietly and carried yourself respectfully – not like the stereotype of the network broadcaster -- people would talk to you, because they needed to tell their story. The man described watching his house tumble down Buffalo Creek, with his wife and children inside. He said they had no warning, despite the heavy rain on Friday. They all knew the earthen dam was up on the hill. Perfectly safe, the coal companies said. Then again, coal companies claimed coal dust was good for you. Could cure the common cold. * * * In my first hours in West Virginia, I got very lucky, in the journalistic sense. This was before computers and the Internet and cell phones. I needed a landline to call my story to the office in New York, so I knocked on a door, and an old lady let me use her phone, and then she invited me to stay for supper. After we said grace, she and her grown son casually mentioned that a friend of theirs had been up on the hill trying to shore up the earthen dam that morning. As the water exploded from the dam, their friend had suffered a nervous breakdown and was in the Appalachian Regional Hospital down in the valley. Poor feller, they said. That piece of information told me the coal company had known the dam was in trouble for hours before it blew. Yet the valley was not warned. The next morning the sun was out, and I found a lawyer from the regional coal company. I indentified myself as a reporter from the Times, and casually asked about the relationship with the major energy company in New York. He said the company still had to investigate the cause, and he added, “but we don’t deny it is potentially a great liability.” When the story appeared in the Times the next day, the lawyer denied saying it, but I let them know I had very clear notes in my notepad. And to this day, I still have that notepad, sitting right here on my desk, and every notepad I have used since. You just never know. * * * With the 40th anniversary coming up, I got in touch with Ford Reid, who was a photographer for the Louisville Courier-Journal back then, and has remained my friend ever since. Ford was at Buffalo Creek for over a week. I asked him to jot down his impressions, and he described the narrow valley as looking like “pickup sticks.” Ford described the scene at the high school: “Families huddled in corners with Red Cross blankets and perhaps a few things they had managed to grab before scurrying up the hillsides to avoid the wall of water." Ford added: “Military search and rescue helicopters used the football field next to the school as a landing area. At the first sound of an incoming chopper, people would rush out of the building and toward the field, hoping that a missing relative or friend would step off the aircraft. When that happened, there were shrieks and tears of joy. But it didn’t happen often. Mostly there were just tears.” * * * We all went to funerals in the next days, hearing the plaintive wail of the mourners and the mountain church choirs, a sound that still cuts through me. My original reporting that the company had a man on a ‘dozer up on the hill during that heavy rain held up, as survivors told their stories of not being warned. In the years to come, the testimony of the survivors was used in three class-action suits that yielded a total of $19.3-million, according to the records. I do not know how that worked out for the 5,000 people displaced or killed by that flood. From what I see and hear, nothing much changes in Appalachia. Nowadays, I hear people talk about the solution for the energy crisis. The industry and politicians like to use the phrase “clean coal.” Aint no such thing. * * * For more about Buffalo Creek, I suggest: http://appalshop.org/channel/2010/buffalo-creek-excerpt.html http://www.wvculture.org/history/disasters/buffcreekgovreport.html http://wiki.colby.edu/display/es298b/Buffalo+Creek+Disaster-+WHAT |

Categories

All

|