|

The message came from a colleague in one of the danger spots in the world.

“I hope that you've got a column in you on Beckenbauer's passing. I'd love to read it.” Ummm, frankly, I had not thought of writing a word about the passing of Franz Beckenbauer, the great German soccer player, last Sunday. I figured the NYT had already mustered two of their surviving sports experts who produced a worldly obituary of the man known as “Der Kaiser.” Beckenbauer was “Der Kaiser” for his smooth play in winning a World Cup on the field in 1974 and another World Cup as the manager of the German team in 1990. I saw Beckenbauer glide serenely through his final years with the Cosmos in the strange new world. Like a lot of great world footballers at the end of their careers, he seemed to be in the U.S. for the money as well as the serenity of living relatively un-noticed in the streets and restaurants. Beckenbauer had a great rep for having played the 1970 World Cup semifinal with a dislocated collarbone (some reports say the collarbone was broken.) For his strange adventure in the U.S., he was surrounded by teammates who out-shone him in charisma – Pelé, just to drop a name, plus the rock-steady defender Carlos Alberto and the solipsistic striker Giorgio Chinaglia. Then Der Kaiser went home. In 1990, in Rome, I was impressed by Beckenbauer after winning the World Cup as German manager. He was giving a press conference at the front of the swarm of soccer scribes, and spotted Lawrie Mifflin of The New York Times, who had covered his Cosmos days. She was standing on a chair to ask a question, and Beckenbauer said, "Hello, Lawrie. How's New York?" The NYT obit by Rory Smith and Andrew Das more than handles the Beckenbauer career and his life, inevitably more complicated than 90 minutes on the pitch. The most impressive thing I know about Der Kaiser is that he was part of the classic Monty Python skit about the big match between philosophers – Greeks vs. Germans, three and a half minutes of inspired name-dropping and turgid pondering. Twenty-one famous philosophers and one footballer. Franz Beckenbauer – “a bit of a surprise,” emotes the classically British commentator. For laughs, the skit needed a famous footballer in the midst of the thumb-sucking, and it has Beckenbauer. ( I have consulted the Web and written to a couple of knowledgeable colleagues, but nothing suggests it was really Beckenbauer.) The point is, one suave sweeper gives a classy note to the big event. I don’t even know how the DVD found its way into our household, but I used to watch it whenever grandson George paid a visit, and we howled at the hapless posturing by men in robes, men in suits. Franz Beckenbauer’s greatest moment. What did he think of it? Wish I knew. *** Note to my pal in a danger spot: Hope this answers your question. Be safe. GV *** The NYT obit: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/08/world/europe/franz-beckenbauer-dead.html Bless its heart, Wiki has a lush section about the Philosophers’ match: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Philosophers%27_Football_Match I am so thrilled that the New York Times obituary editors ran a lovely obituary of Joe Christopher, a member of the early New York Mets – and my friend over the decades.

Joe touched a chord in me because he was mysterious and deep. I have learned more since he passed last week, from his daughter Kameahle Christopher. I also collected memories of Joe from two of his old teammates. In case you miss the NYT obit, here it is (for those who can access it). It is written by Richard Sandomir, now an obit writer, but previously a star sports-media critic (back when the NYT had a sports section.) https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/05/sports/baseball/joe-christopher-dead.html I became intrigued by Joe Christopher in the first year of the Mets when he was a backup outfielder. Joe was from St. Croix, apparently the first player born in the Virgin Islands to play in the major leagues. He was a mix of cultures and languages, introverted, but also comfortable chatting with some of the young Chipmunk writers covering the club. “I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am,” he would say, softly. Sometimes he would chat with me about mysterious religious trends. I don’t claim I understood, but I think he sensed he had a friend. He was up and he was down with the Mets but in 1964 he played regularly and batted .300. (The obit tells how in the final game he dropped a bunt single in front of old Ken Boyer of the Cardinals to pretty much clinch the distinction of being a .300 hitter. In the pressbox in St. Louis, I almost cheered out loud.) His career sputtered again in 1965 and he was soon gone from the majors. Recently, two former teammates had nice things to say about Joe: Larry Elliott, a fellow outfielder in 1965, sent this memory: “I was trying to break up a double play against Philly. I did not get down in time and Ruben Amaro hit me in the back of my head with a throw. It was my fault. I was in the hospital for five days and Joe was the only one to come and visit me." My e-pal, Bill Wakefield, sent his memory of 1964, when he was a rookie out of Stanford and reported to the Mets’ spring hotel in St. Petersburg, Fla. “The front desk says, yes, we will give you a room, and assign your roommate. So I take my suitcase to the room. Open the door, and inside is a startled Joe Christopher. I said, ‘I’m Bill Wakefield and I’m your roommate.’ He seemed surprised but said, fine” (Wakefield doesn’t need to note that Blacks and whites were not rooming together in those days. And Christopher, who had been introduced to segregation in the U.S., was surely aware of that.) Shortly, Wakefield received a call from Lou Niss, chain-smoking, worry-wart travel secretary of the Mets “Come to come to the lobby immediately. I assume it's to get instructions -- don't drink in the hotel bar -- that's Casey's spot -- don't be late for the bus -- wear shower shoes on the bus not spikes, etc. “He says – ‘ Bill we are moving you in with Larry Elliott -- make the change immediately.’ And sort of as an afterthought, he said -- I paraphrase – ‘Baseball has made progress but we are not ready for black and white roommates yet." “I have no idea -- I just want to do all the right things. So I go back down to the room -- Joe is still there -- he kind of smiles at me -- and I said Lou Niss has assigned me a different room. “I always worried that Joe thought I had complained and that was the reason for the switch. I really didn't care. "So I packed up and moved to Larry's room.Joe never mentioned it again. He and I became pretty good friends. “Joe and I laughed about it over the course of the season. He even got a big smile on his face and would say ‘Nice going, Roomie!!!’ Great guy.” I have one more memory of Joe, who could wiggle his ears with the best of them. A knot of Mets writers were taking the sun behind the Mets’ dugout during a game in Chicago in May of 1964. As the Mets frolicked to an unforgettable 19-1 final score, Joe would trot in from right field after each inning, levitating his cap with his ears – just for the writers’ sake.” Joe’s major-league career fizzled but we kept running into each other. In the late 60s, I was in Puerto Rico writing for Sport Magazine about Frank Robinson managing a team in the winter league. I was at a game in Caguas when I spotted Joe playing for Santurce…and we agreed he would ride back in my rental. Then he won the game with a grand-slam homer in the ninth inning and the fans were so annoyed that they made motions to tip my car over. We laughed about it all the way back to Santurce. I always reminded him how he almost got me killed. Joe and I ran into each other in the 1980s near Times Square. He was carrying a large rectangular portfolio used by artists to protect their work. He came up to the Times for a while, but I never saw his work -- part of the mystery of Joe. The other day, I chatted with Kameahle Christopher, a paralegal with Amtrak, who lives outside Baltimore, and asked about her dad’s inner life. “He was interested in pre-Colombian art,” she said. “He was in touch with the ancients, the Olmecs and Mayans. He was into numerology…would ask your birthday, would predict things,” Kameahle said. “He was gifted spiritually.” I asked her about her dad’s childhood and she said he was raised in Oxford, a small settlement in St. Croix. “He grew up in a small house in the mountains,” she said. “He walked everywhere, and when he came home at night, he learned to follow the North Star. He said, “‘I’m not going to grow up like this.’ Nobody had ever left the islands. He endured hardships, but he used to tell himself, ‘I’m Joe from Oxford…and if I have to walk, I’ll walk.” In his later years, Joe wanted a job teaching baseball; “he carried his baseball gear in his car,” Kameahle said. Joe would coach somebody for the joy of it, remembering how much he had learned from coaches like Rogers Hornsby, Sheriff Robinson, Paul Waner – and his driven roommate with the Pirates, Roberto Clemente. After talking with Kameahle Christopher, I felt I knew her dad better – where his inner strength came from, standing in the clubhouse, a marginal Met, telling young writers from New York: “I’m a better ball player than you guys think I am." Kameahle’s loving portrayal made me miss him even more. ## In the terrible year of 1968, with war raging in Vietnam, with MLK and RFK being assassinated, a sound emerged from a funky pink house in the Catskill mountains that some of us had been awaiting, whether we knew it or not. “It’s like you’d never heard them before and like they’d always been there,” Bruce Springsteen would say, several decades later. This is true. I can attest to the feeling of desperation in the late ‘60s, and how it was tempered by the music from five troubadours – one from Arkansas and four from Canada. (Toronto was a melting pot for music that would be heard around the world.) The five musicians brought their separate gifts, in a visual mishmash of floppy country thrift-shop clothes, indistinguishable in their very white slouches. But gradually we sorted out Richard Manuel from Rick Danko from Levon Helm – the token southerner -- from Garth Hudson – now the last survivor, with his weird beard and instrumental sounds – and from Robbie Robertson, who died Aug. 9 at the age of 80. Robertson’s life is captured in the excellent NY Times obituary by Jim Farber: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/09/arts/music/robbie-robertson-dead.html Robertson came off as the dominant Band member in the documentary, “The Last Waltz,” by Martin Scorsese, which was made as the Band broke up, with a glorious final concert cast, in San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom on Nov. 25, 1976. Scorsese was obviously taken by Robbie Robertson’s charisma and intelligence and ambition, which helps explain why the boys were breaking up the band. When the movie was released in 1978, Marianne and I took our youngest, David, to see it in The Village (Dave clarifies all in his comment, below) -- the start of a family tradition. Every year at Thanksgiving, David pops in a DVD of “The Last Waltz,” as we give thanks for life and also the music and point of view of the Band, including Jaime Royal "Robbie" Robertson. I had a few glimpses of The Band. In 1974, as a news reporter, I was assigned to cover the Long Island and Manhattan stops of a national tour by Bob Dylan, and the five musicians who had melded as members of Dylan’s band. The only Band member I actually met was Levon Helm, when he was cast by Michael Apted to portray Loretta Lynn’s father in the movie, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Another time, I saw Danko and a haggard Manuel perform at a Pete Fornatale fund-raiser for a food charity, in the Village, not long before Manuel committed suicide. In 1980, there was a “grand opening” for the movie “Coal Miner’s Daughter” in Nashville. Maybe a bit sloshed, Levon played backup to Loretta and Sissy Spacek as they sang some of Loretta’s greatest hits. He was so modest, did not need attention. I never did meet or eyeball Robbie Robertson, but his mystique grew in his post-Band years. People came to know that his mother, Rosemary Dolly Chrysler, was a Mohawk, raised on the Six Nations Reserve near Toronto. His actual father (who died young in a car accident) was not named Robertson but rather was a gambler who was Jewish. “You could say I’m an expert when it comes to persecution,” Robbie Robertson wrote in his memoir, “Testimony,” issued in 2016. One of my favorite Robbie Robertson songs is “Stage Fright,” about a singer – maybe Bob Dylan himself, who comes off very nicely in Robertson’s book, offering a functional car to the young guitarist coming to play backup in Dylan’s band. https://www.google.com/search?q=lyrics+stage+fright+the+band&rlz=1C1GTPM_enUS1061US1062&oq=lyrics+stage+fright&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBwgAEAAYgAQyBwgAEAAYgAQyBggBEEUYOTIICAIQABgWGB4yCggDEAAYhgMYigUyBggEEEUYPNIBDzEzMDU5MzU3NTRqMGoxNagCALACAA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 Others think the song is about young Robbie Robertson himself. Still coalescing as a band, the five musicians made a pilgrimage to a soul-music center in Arkansas, and invited Sonny Boy Williamson for some soul-food in a Black neighborhood. Home-boy Levon tried speaking polite Arkansan to a couple of white cops, only to have the five run out of town. Another of my favorite Robbie songs is “Acadian Driftwood,” about French settlers on the Canadian coast, some of whom later migrated southward to join relatives in Louisiana, only to realize they were still outsiders: “Set my compass north, I’ve got winter in my blood.” As the settler prepares to go “home” to Canada, the language shifts into French: “Sais tu, Acadie j'ai le mal du pays” (Do you know, Acadia, I'm homesick.) In later decades, Robertson performed and wrote music that reflected his Mohawk genes: https://www.samaritanmag.com/musicians/qa-robbie-robertson-why-he-kept-quiet-years-about-his-heritage In his later years, Robertson gravitated to Los Angeles, but he continued to write and perform songs that spoke for outsiders, including himself -- part shtetl, part rez. ###  Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Here on the Manhasset-Port Washington tectonic plate (if there is such a thing), some people still feel the rumbling from Jim Brown, local guy, who died Friday at 87. They remember the earth trembling when Brown crashed into opponents in most of his five sports. (Correct: five sports.) They also remember the impact of his loyalty, when he chose to come home to Long Island. Brown was many things to many people (including a felon serving a few months for misbehavior toward women.) Bad side and all, Brown was surely an epic figure out of ancient legends – from Beowolf to Babe the Blue Ox to John Henry, the steel-drivin’ man. Some people remember, first-hand. I called my pal and neighbor, Paul Nuzzolese, who played three sports at Schreiber High in Port Washington. Paul’s family used to run a visible ice-and-wood business with trucks rumbling all over the metropolitan area. Paul played guard in football, was on the basketball team, and was a lefty pitcher on the Port baseball team. The plan for Jim Brown was to throw off-speed, not give the big guy something he could hit. And if you could induce Brown to chop a grounder, it was wise to avoid a collision. Were baseball opponents intimidated by the sight of Jim Brown on the basepath? Paul called me back Sunday morning after he recalled pitching at home against Manhasset, and being taken out when the game was tied after a regulation seven innings. That gave him a good view of Brown's 360-foot perambulation of the bases: "Brown hit a squibbler down the first-line," Nuzzolese said. "You know how hard it is to field a squibbler." Harder with fully-grown Jim Brown hustling down the basepath. (No names mentioned of the Port fielders.) The ball got past the first baseman, into right field, and Brown took off for second, and continued toward third. The Port third baseman waited for the throw, but was wary of Brown barrelling down on him, and needless to say Brown wound up scoring on the aforementioned squibbler. Port lost the game, but the fielders retained their knees, and their wits. Still, like Jim Thorpe and Michael Jordan, Brown was not a great hitter. “It was his fourth sport,” Paul said respectfully on Friday when he heard his old opponent was gone. In order, Brown played football in the fall, basketball in the winter, was a high jumper in track and field, and somebody will have to explain to me how he managed to play baseball and lacrosse in the spring. There are tales of Brown playing in a baseball game, and when Manhasset was not in the field, he would leap a fence to and take a turn at the high jump, and then return and take his turn at bat. How did Brown come to Manhasset, at the base of Manhasset Bay, a few minutes from Port Washington? Born on Feb. 17, 1936, in coastal St. Simons, Ga., Brown came north with his mother, who cleaned houses in adjacent Great Neck. But Manhasset introduced the young man to civic leaders and coaches who promised him he would be comfortable in their school, and he wound up registered at Manhasset. He soon made himself felt – particularly on the football field. Paul Nuzzolese, 86, was a guard, bulked up over 200 pounds, who saw and felt Jim Brown up close. He recalls a fellow lineman -- “Big Joe, six-foot-three, built like Hercules, had a collision with Brown in the open field – never was the same.” My friend was talking on the phone from Florida; I could hear the shudder in his voice. (I have to proudly add: My pal Nuzzolese is now a member of the Wagner College athletic hall of fame.) As good as he was in football, Jim Brown was said to be the best lacrosse player who ever lived. It was impossible to dislodge the ball from the webbing at the end of his lacrosse stick, tight in his powerful hands. The legend is that Lefty James, the football coach at Cornell, wandered over to watch a Syracuse-Cornell lacrosse game one spring and blurted, “My God, they let him carry a stick?” (I think my late pal Dick Schaap, who played a bit of lacrosse, may have told me that story.) The money was in the National Football League, and Brown was the best, or very close to it. His path took him to the movies and some notoriety in his so-called private life and also a major role in Black activism of the ‘60s and well into this century. All of that is covered in the great coverage in Saturday’s New York Times and surely everywhere else. And then there were the homecomings. In 1984, Brown had mellowed enough to accept the induction into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, but obdurate as he was, he would only show up if the ceremony was held in his adopted hometown of Manhasset. He honored Ken Molloy, civic leader, and Ed Walsh, football coach, and others who treated him with respect, more than just a five-star athlete. I made the short drive to cover Brown’s induction. In the informal moments, I introduced Brown to my son, then 14 years old. “Nice to meet you, David,” Brown said, in that deep voice, shaking hands vigorously. I distinctly remember a crunching sound, although David does not quite remember it being quite that bad. Brown came home other times. One of his Manhasset teammates, Mike Pascucci, had done well in business, and had become a booster of one of the great institutions on Long Island, or anywhere – then named Abilities, Inc., now named the Viscardi Center, after the founder, Dr. Henry Viscardi – in nearby Albertson, L.I., where people are helped to work, to play, to live. (FYI: Edwin Martin, a frequent contributor to this site, was a long-time leader of the Viscardi Center and is a pioneer of services for the disabled; his wife Peggy has been an activist for easing young people into jobs.) Clearly, the Viscardi Center attracts good people. Once a year or so, Pascucci would invite his old teammate to visit the center. “They had a celebrity night,” Paul Nuzzolese recalled Friday, “They’d get athletes like Jack Nicklaus, Gale Sayers, Mike Schmidt, signing autographs. I saw Jim Brown get down on his knees and talk to those kids, and he would say how proud he was to be there.”  Jim Brown never lost his dedication to causes. I ran into him in the ‘90s, at some gathering in the city, I cannot remember the cause – health care and support for broken old football players, or racial causes. Whatever. Jim Brown was wearing a fez over his rugged skull, displaying a familiar hard look below the fez. Omigosh. I felt we were back in the late 60’s maybe in People’s Park in Berkeley, maybe outside Madison Square Garden or some other place that needed an attitude adjustment. The old days were back: Harry Edwards. Bill Russell. Roberto Clemente or Curt Flood giving writers a seminar in the clubhouse. Richie Havens. Nina Simone. Protest songs. The hallowed John Lewis. I saw a puzzled look on the face of a Black journalist, half my age, and I kind of giggled. Jim Brown’s scowl made me feel young again. And on the Manhasset-Port Washington peninsula, the earth still shudders from the powerful athlete who once played here. A young Black man is shot knocking at the wrong door. A young woman is killed after her car pulls into the wrong driveway. And then there are the police shootings. People are trigger-happy, and I know when it got worse – back in 2016 when a real-estate grifter and reality-show character ran for the presidency. He was sending a message to a huge segment of America that it was time to get tougher. Just look the sneers and cheers behind the bad actor, as he goads them into action. People were getting dumber, by choice, and a swath of the country welcomed his message to gear up. America as a reality show was on my mind as I read an analysis of the late Jerry Springer by Jane Coastan in The New York Times on Saturday. She describes Springer as a kind of Dr. Frankenstein who got caught up in his own monster, but she also suggests that he knew what he was doing, all along. Reality shows pay well. I never watched the grifter’s show (having met him a few times) and I never watched Springer’s show, either but I did pay attention to him because he was another Queens guy (Forest Hills HS) and had gone into politics in Cincinnati when I was living down-river in Louisville. Turns out Springer and the more dangerous reality show buffoon were both descended from Germany – one was a Jewish refugee, born in a makeshift maternity ward in the Underground in wartime London, the other whose father attended Nazi Bund rallies and lived in posh Jamaica Estates, Queens. They both understood their audiences. One went into politics to play to the angry white people in America, the other went into television to play to people who liked life on the violent and kinky side. The young grifter also knew the violent side – somebody who would know has told me about the grifter’s father being bandaged all over, recuperating at home after some kind of organized beating. Lesson learned: Just give some orders and people will go out and break some bones. That’s what he was suggesting at his rally in Las Vegas in February of 2016. His subtle political message: How he would like to punch that heckler. Just let me at him! But America has become too soft to allow that kind of frontier justice. Still, thanks to the gun merchants and the Republican lawmakers and the sour Americans waiting behind their front doors, we have quickie frontier justice – and students being shot up in school, and legislators banning the elected messengers. Plus, Charlottesville. Good and bad on both sides, right? America has always had guns. I moved to cover Appalachia in 1970, and some journalist pals at the Louisville Courier-Journal (now terminally Gannett-ized) told me about the television journalist in 1967 (from dear, sweet Canada!) who ignored the warning not to intrude, and was shot dead. The recluse served a year. Yes, I thought about that every time I needed to knock on a door in some distant holler. But now the violence is spreading. People go to political rallies, packing. The grifter is finally facing legal justice, after a wasted year from the sclerotic Justice Department. And good grief, he's threatening to run again. RIP, Jerry Springer. All he did was give Americans what they liked in bestiality and incest and brawling. Seems so innocent now. (Marty Goldman has written this tribute to Michael Spivak, our mutual classmate at Jamaica High School in Queens in 1956, and something of a folk legend. Marty was the valedictorian and Michael was sixth in our class -- quite an accomplishment for both, considering there were over 850 June graduates. Let me hastily add: I was in the third quadrant.

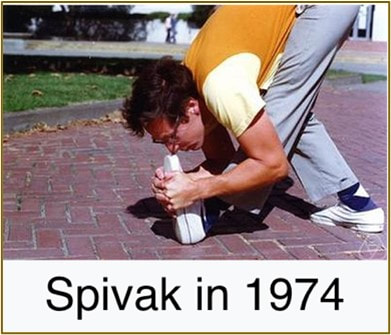

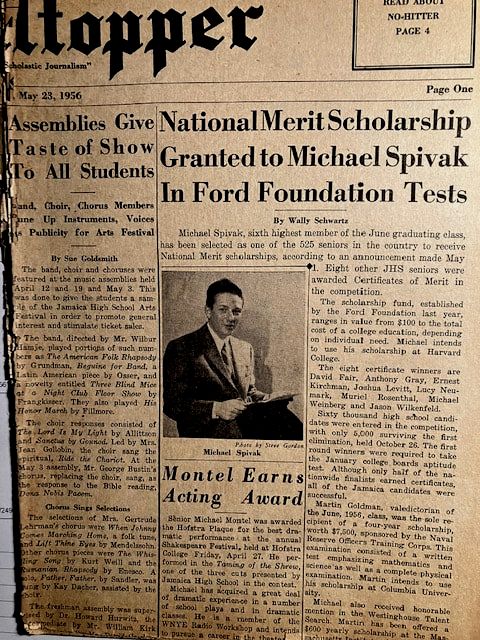

By Marty Goldman It is with sadness that I report the passing of our Jamaica High classmate, Michael Spivak. Michael may not have been known to everyone in the Class of ’56, but he was my friend and he just bowled me over with his math brilliance. He was barely 16 at graduation. There he received a top Math Prize, won an award for English and accompanied our Choir on piano. I remember a conversation we had while we were waiting to get into the JHS cafeteria. He was telling me about a book he was reading for pleasure - Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica, which explored the foundations of logic and set theory. At that point I realized that I didn’t have his degree of the curiosity, patience and deep intellect required to become a successful career mathematician. So, what became of this precocious, talented person? Simply this: his writings, sense of humor and reclusiveness made him a legend in the world of mathematics! After JHS, Harvard and a PhD in Math at Princeton under the renowned John Milnor, he began writing math textbook after textbook. However, these were no ordinary textbooks! Consider, for example, what is said about his 1967 book, Calculus. Bloggers call it, “The greatest Calculus book of all time,” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oave4Z939as) and “The most famous Calculus book in existence,” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=huSD6GysL6k). A review article by the Mathematical Association of America (MAA), states, “This is the best Calculus book ever written” (https://www.maa.org/press/maa-reviews/calculus-4). It was not his first Math book. Two years earlier, at twenty-five years old, he published a little textbook, Calculus on Manifolds: A Modern Approach to Classical Theorems of Advanced Calculus, which has been translated into Polish, Spanish, Japanese and Russian. This book explained what is known about Calculus on surfaces and volumes in higher dimensions – even beyond three. The book is described as, “elegant, beautiful, and full of serious mathematics,” in a review by the MAA. While writing his books, Spivak taught as a full-time Math Lecturer at Brandeis University. In 1967 he won a year-long National Science Foundation Fellowship to Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, where Einstein had taught and struggled, in vain, to develop a theory unifying gravity with the other fundamental forces in nature. When Spivak returned to Brandeis it was as Assistant Professor of Mathematics. At this point the usual academic career move for a mathematician would be to publish significant original research papers, which serve as the imprimatur for promotion to Associate Professor and, eventually Full Professor with tenure – a lifetime job. However, this was not the path followed by Michael Spivak, who turned away from the customary academic career in favor of an iconoclastic career as an author – a prolific, much-admired sole author – and eventually as a publisher and science popularizer. During his three years as Assistant Professor of Mathematics at Brandeis, Spivak continued to write books, while teaching classes. In 1970, his last year as Assistant Professor, he published the first two volumes of what would become a five-volume masterpiece with the daunting title, Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry. More later about the sensation this set of books produced in the math community. After leaving Brandeis, Spivak was no longer on a conventional academic track, although he continued to give lectures at universities like Berkeley and in Bonn, Germany. By 1975 the first edition of the five volume, Comprehensive Introduction was published. Thus, by age 35 Spivak had published seven books. His reputation among mathematicians was growing but it was increasingly difficult to track his whereabouts and impossible to learn anything about his personal life. He began to acquire a cult following. Spivak’s new projects were often surprising and witty. He created a Canadian TV series, Science International, featuring many short segments dealing with an eclectic assortment of topical scientific and technical issues. Science International was later brought to U.S. TV as, What Will They Think of Next? (IMDB). Next, he founded his own publishing house, Publish or Publish, which produced the second edition of his five-volume opus as well as other works by him and others. In order to deal with the difficult art of typesetting mathematical formulas in his publications he extended the equation-editing program, TEX (pronounced “tec”), and documented his contributions in a treatise entitled, The Joy of TEX. He also invented one of the first gender-neutral set of pronouns called the Spivak Pronouns and wrote The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Calculus. In 1985 he received the American Mathematical Society’s highest award for expository mathematical writing, the prestigious, Leroy P. Steele Prize for his five-volume Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry. His PhD advisor won the same award, years later. The citation from the American Mathematical Society reads, “In the ten years since its completion, this work has become a kind of classic of its own, providing the reader with important insights into the development of the subject, a well-selected set of central topics, and a unique and exhaustive annotative bibliography. Furthermore, it is written in a lucid and informal style that makes reading it a pleasure. An earlier "classic" by Spivak is his Calculus on Manifolds, one of the first books to make available to an undergraduate audience the basic concepts and techniques of differentiable manifolds and differential forms.” (Notices of the AMS., October 1985 Issue 243, Pgs. 575-576) His response was, “It was as gratifying as it was surprising to learn that I was to receive the Steele Prize for my books on differential geometry. When I made my first intrepid, not to say foolhardy, attempts to fathom the multi-media world of differential geometry, I certainly hadn't anticipated completing a work of such outlandish proportions. I hope this award will encourage others on similar ventures and show that they can be accomplished even from the periphery of the academic world.” (Notices of the AMS., October 1985 Issue 243, Pgs. 575-576)  Spivak had a lifelong interest in Physics and wrote a book called, Physics for Mathematicians: Mechanics. It is described in a Wikipedia article about him, which contains the photograph below, left. What is he doing in this photo and how is this pose even possible? It is rumored that in each of Spivak’s books there are hidden references to yellow pigs, an idea Spivak apparently came up with at a bar while drinking with David C. Kelly. Michael Spivak’s productive, colorful and unconventional life sadly came to an end on October 1, 2020, at age 80 in Houston, Texas. Details, unfortunately, are not available. We can all justly take pride in the lifetime of accomplishments of our classmate, Michael Spivak. *** From George Vecsey: My thanks to Marty Goldman for volunteering this informed essay. I only wish more had been written about Michael Spivak when he passed, after breaking a hip, according to snippets on the Web. One of Spivak's accomplishments has widespead implications these days: his scholarly creation of gender-neutral pronouns, very much an important subject these days. https://wiki.c2.com/?SpivakPronouns https://www.liquisearch.com/spivak_pronoun https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/105747 https://www.quora.com/What-impact-did-Michael-Spivaks-books-have-on-you-He-died-in-2020  The May 23, 1956, issue of the Hilltopper, with the lead story announcing that Michael Spivak had been awarded a National Merit Scholarship and that Martin Goldman had also earned a scholarship. The article was by Walter Schwartz, the editor for much of the year, which is why I call him "Chief." Hail to the chief for digging this clip from his files. ALLAN MISSED HIS WIFE Allan Fishkind took care of people, most notably his wife, Joan Smith. She was the star, the name on the bustling shop, Joan Smith Flowers, with her talent and hearty personality that charmed friends and clients alike. Allan, big and strong and dependable and low-key, drove the flower arrangements into toney clubs and hotels in the city or around our town, maintaining the shop, fixing stuff. Joan was the love of his life, and vice versa, both of them coming from earlier marriages, with children. With friends, Joan would unwind, tell stories of her Dickensian childhood, leaving home in her mid-teens, surviving in a Y. Allan did not tell stories. He was tall, like Joan, usually with an inscrutable smile on his face. Some attributed his mellow presence to what he called his health regimen. He also found time to take care of a blind friend who bravely lived in her own house. In the days after 9-11, he collected clothing and blankets and drove them to the collection point at the edge of the horror scene. In our old waterside commuter town, Joan and Allan were townies. I remember them talking about a bar that had line dancing on weekends or a spaghetti-and-meatball fest for some good cause. Allan took care of Joan during her illnesses, which neither discussed, even when the shop closed down. Two summers ago, they popped over to our deck, Joan as chatty as ever. My wife loved Joan, knew her well, and sussed out that Joan was saying goodbye, which turned out to be true, on Sept. 20, 2020. There was no service, no fuss, but Allan’s goal was to arrange a memorial bench for Joan at the edge of Manhasset Bay, across the street from Diwan, a favorite restaurant. He accomplished this on a sweet Sunday morning, Sept. 5, 2021, greeting friends from all their circles, giving a sweet talk about Joan, the star. Then he settled into a routine nobody could quite chart – but clearly, life without Joan was not the same. This past summer, Allan materialized on our deck, settled into a chair, and chatted about himself more than he ever had before – even alluding to his own youthful hard times. We made him an herbal tea, and he chatted some more. He looked thin, and it turned out that other friends were telling him he should check with a doctor, but he delayed until he was days away from death from pancreatic cancer. Word got around that Allan had been buried by a son, somewhere upstate, far from the town Joan and Allan had graced. When I go for a walk along the bay, I stop by Joan’s bench and think of both of them, together. Joan and Allan.  Caryle and Michele Caryle and Michele MY COUSIN CARYLE ADMIRED JUDITH JAMISON Among my earliest memories are two Spencer cousins. Art died last year and his kid sister Caryle passed this year. I can remember a lot of giggling when we were little and our families would get together. My wife and Caryle shared an interest in family genealogy, and would compare notes – and on the rare times we got together, Marianne says, Caryle retained an adult sense of humor. Also, my brother Peter loyally visited Caryle in her final, uncomfortable years. But the person who knew Caryle best is her daughter, Michele, now living in England. Michele wrote a lovely tribute, which includes the memory of her mom being “a bit of a tomboy, and loved being outdoors and in nature,” as a girl. Michele recalls walks on nature trails and horseback riding and bird-watching and home crafts, making Christmas decorations and fruit cakes “that took months of soaking in brandy and had the weight of a doorstopper.” Caryle fed local birds like cardinals and hummingbirds and took in stray cats and often had a horse or two nearby. Michele added: “What I most admired about her was her complete lack of prejudice or bigotry.” Then Michele added a surprise to me: “The second was her love of dance. She didn't make a show of it, so it's easy to think it wasn't that important to her. I've come to suspect it was a deep part of who she was. “Mom loved ballet and modern dance and took lessons in both during her early adulthood. She even took part in an interpretive dance troupe at our church. She loved musicals that featured dance, and I have many childhood memories of staying up late with her to watch old musicals on television. “What I didn't fully comprehend until many years later was the depth of her interest. That realization came at my college graduation. The commencement speaker was American dancer and choreographer Judith Jamison. Mom surprised me by not only having heard of her but knowing the full history of her career and having seen her dance with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. It was the only time I've ever seen her star-struck. She was desperate for an autograph but couldn't work up the nerve to approach her.” As it happens, I once interviewed Judith Jamison and was struck by her elegance, her intelligence, her long expressive hands and eyelashes. Whenever I think of my cousin Caryle, with her animals and her crafts, I will hold on to this vision of her, adoring the glamorous and thoughtful dancer. Historian of a Steel Town Charles E. Stacey never left his hometown. He went to school in Donora, Pa., alongside the Monongahela River, when the mills were running, and clogging the lungs, when Stan Musial was the most famous native. Dr. Stacey stayed in Donora and taught history, and one of his pupils was Reggie B. Walton, a football star with a brain and a will. “I can visualize him in American History, near the back, fourth row,” Dr. Stacey said a few years back. “Near the window. Totally attentive. Everybody liked and respected Reggie.” Reggie Walton went away to college, and law school, and became a federal judge known for his independence, his dedication to fight drugs. Charles Stacey became the superintendent of schools, and he and his wife, Sue, remained on McKean Ave., the main drag, with its empty movie theatres and restaurants. Somebody had to be the voice, the memory, of Donora, available to teach the history of the region to visiting students and reporters. When I was writing the biography of Stan Musial in 2011, I met Charles (“call me Chuck”) Stacey, who was running the Donora Historical Center, in a deserted storefront on the main drag. I asked if he could put me in touch with his star pupil, and a few days later my phone rang and a voice said, “This is Reggie Walton. Dr. Stacey asked me to call you.” And when Donora honored the star baseball player, Ken Griffey, Sr., not too long ago, Judge Walton made it back to be with his old teammate. The two stars stood alongside their teacher. Dr. Stacey died on April 25, at the age of 90. Every small American town deserves a Charles Stacey, who remembers the people who settled and worked and dreamed. Lucky Donora. It had Charles Stacey. BEAU GESTE BY AN OLD FRIEND Last month I heard from Sam Toperoff, athlete and writer, that Thierry Spitzer had died in a car accident. I remembered Thierry as an active pre-teen, but in fact he was 58. At the memorial for Thierry in the old neighborhood in Queens, I caught up with his sisters, AnneLise and Karine, and I told them my two daughters always felt Thierry had a certain life force, as a long-haired active kid. I hadn’t seen Thierry since he was an early teen but I knew he had worked for decades as a waiter at the Hotel Carlyle in the city. His dad, Philip Spitzer, who died last year, had been an agent for me and also for Sam Toperoff, who now lives in the French village near the Alps, a second home for Thierry’s mother Anne-Marie. Sam, being a writer, told me about the adult Thierry:“A very sweet and funny man. Less than two months ago, he was sitting in my big comfortable chair in the living room talking about how good it was to get back to the Carlyle after two years without work and how sad Manhattan was still. “He came over most summers to stay with his mother and Karine in the village. We talked sports as though we really knew stuff. We walked in the mountains when his knee permitted.” Thierry had played basketball and softball in the French village, and also played tennis. “I just remembered this,” Sam wrote. “Thierry was in the semi-finals of the big tennis tournament here, big crowd, tough match, and in the third set he called an opponent’s ball good after the judge had called it out and conceded the point, it cost him the match. I’ve never forgotten that. So revealing.” That's how I will remember Thierry. FAREWELL TO MY ROOMIE When Julie Bretz got me in touch with her dad early in 2022, Joe Donnelly and I greeted each other on the phone as “Roomie.” This dates back to when and the Newsday’s sports editor had us share a hotel room during the World Series in St. Louis, to save a few bucks. I just might have griped a bit about Joe's smoking…but forever more, Joe and I were “Hey, Rooms!” -- just like ball players. While others recall the great stories Joe wrote, let me talk about another skill of my roomie: Joe Donnelly could throw. When we called him “Joe D,” it was homage to another great fielder with a strong arm, many decades ago. I recall Newsday softball games but also a few baseball games at a mid-day empty Shea Stadium or Yankee Stadium, before the real players arrived for work. Joe could roam center field and his throw from the outfield would sting the palm of any infielder or catcher who stuck out a glove. Joe also played touch football – quarterback, of course. I recall him saying his model was Sonny Jurgensen of the Washington NFL team. He could throw the ball 30-40 yards, maybe more, with perfect aim. I know this because we Newsday people used to play touch football in the fall. In those days, Newsday was an afternoon paper, meaning deadlines were long after midnight, but somehow or other we would wobble into a park in nearby Hempstead around 11 AM. A few Mets who lived on Long Island would join us, for the running more than the competition, Joe would shuffle around, not trying to look or act like a pro quarterback, just another scribe who had worked late the night before. But when the ball was hiked, and he had a few counts of “one alligator, two alligator…” and everybody went running off in different angles and Joe would put the ball in somebody’s hands. Joe didn’t gloat or strut. Slinging the ball deep was what he did. Then we would go to a luncheonette and talk about the game, or our editors. Those Newsday games were a highlight of my life, my career, and I suspect it was the same for all of us. I still refer to my Newsday mates as “we” and “us,” just as old ball players refer to all their teams. Joe loved his family, loved to write, and loved being around sports, so in his spare time he would caddie or ref games or serve as an official scorer. and he incorporated the vocabulary into his daily life: For a great view of Joe Donnelly, you absolutely must read the tribute to him by Tom Verducci on the Sports Illustrated website: https:www.si.com/mlb/2022/12/13/joe-donnelly-obit RIP, Roomie. *** Two talented pioneers of sportswriting died this past year – Jane Gross and Robin Herman had to put up with a lot of resistance when they tried to be sportswriters. I am so glad I got to know them and work the locker room and the pressbox with them: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/10/sports/basketball/jane-gross-dead.html https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/02/sports/hockey/robin-herman-dead.html *** Two familiar faces from soccer passed a few days apart in December -- Grant Wahl, on the beat at the World Cup, and Alex Yannis, who was so kind to me when I started to show up in soccer press boxes for the Times. Nobody spans the eras of Yannis and Wahl better than Paul Gardner, whom I call "The Johnny Appleseed of Amercan soccer -- crossing the Atlantic with a Brit's birthright of soccer knowledge, and spreading the lore in his opinionated but yet charming way. Paul's expertise is still vital in the great resource, Soccer America: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#search/soccer+america+/WhctKKXpPXHtTXgdkrqkdzbkpTtmgjKXWwHWphkhvXsPFQmqQGPcCcXTFzpnWHNTblpQKJg Two-long time friends departed this past year:

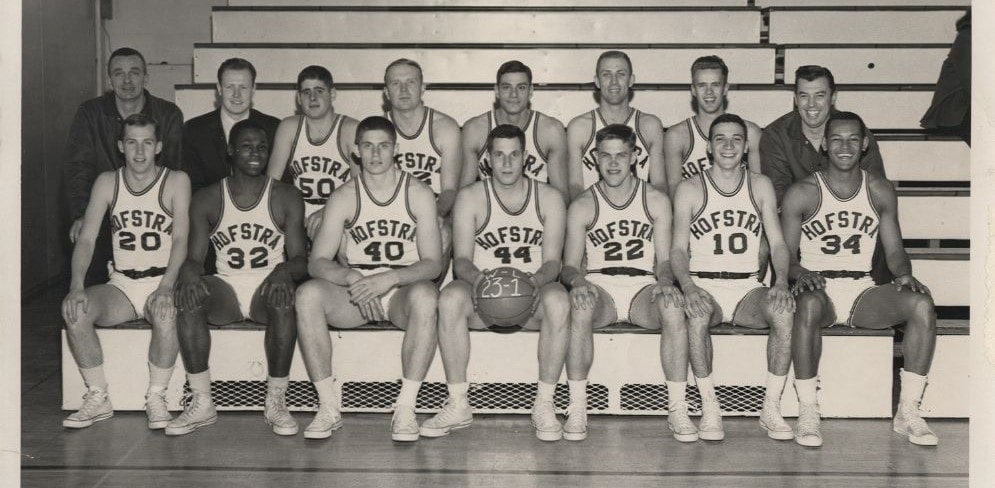

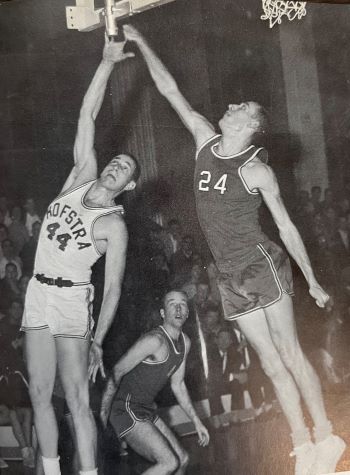

Joe Vecchione was the sports editor who monitored my path to sports columnist. He and his wife Elizabeth, with her charming Newfoundland presence and nursing career, became good friends. https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/joe-vecchione-my-boss-my-friend Stan Einbender and I went to school for nine straight years -- junor high, Jamaica High and Hofstra, where he was the captain and rebounder on the team with a 23-1 record when we were seniors. We both married artistic, strong-minded women. https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/rip-stan-einbender-family-man-rebounder-endodontist I hate that the pandemic has kept us from seeing friends, particularly Elizabeth Vecchione and Roberta Einbender. And finally: we think about Loretta Lynn, who made it so easy for me to help write her autobiography, "Coal Miner's Daughter." Loretta's daughter, Patsy Russell, has kept us in the loop. Laura Vecsey, our oldest, wrote her memories of being on the road with me and Loretta: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/talking-and-writing-about-loretta Loretta was part Cherokee, via her mother, Clara. When she and Mooney bought their ranch west of Nashville, she started to learn more about how the Cherokees were forced from their homes (just a little bit of American history the country never taught us, back in the day.) The Duck River is about 10 miles to the west of the Lynn ranch at Hurricane Mills. Loretta said she could hear the Cherokees crying as they marched along the Trail of Tears. She brought her pride with her on the stage. On Page 16 of the original hard-cover book, Loretta has a few words about Andrew Jackson and other Tennessee people who sent the Cherokees away. In his final hours, Grant Wahl wrote that he had been wrong. He had predicted that the Croatian star Luka Modric was too old at 37 to take the team any further, but after Croatia reached the semifinals on Friday, Grant wrote a mea culpa. Then he went on to write about the second World Cup quarterfinal of the day, and he died, at 48. The circumstances must be examined by American authorities. It’s way too easy for Elon Musk’s new toy to carry kneejerk claims that Grant Wahl was given the Khashoggi treatment, some kind of chemical bonesaw. But we don’t know, not yet. The New York Times and other responsible news agencies quickly examined Grant’s own recent articles mentioning his not feeling well in Qatar, and going to a clinic at the stadium, and he described how other journalists covering this marathon had the same symptoms, from long hours and work stress and crowded press rooms and Lord-knows what kind of travelling microbes. I’ve been there, done that, under the same conditions, during World Cups and other mass events. (More on that, below.)  Grant Wahl was one of the major journalists covering soccer, and had been right about so much, including the repressive air to this World Cup in Qatar, born from scandal – packets of $100 bills to delegates -- in the world soccer body, FIFA. One day at the World Cup, Grant wore a rainbow t-shirt, the universal symbol of support for gay rights, gay existence, and he was held by stadium police, until released. That takes courage. Most people learned after Grant’s death that the rainbow t-shirt was a tribute to his brother, Eric, who is gay. His brother linked the death to Grant’s speaking up for gays, and for thousands of itinerant laborers who have died building these pop-up stadiums in a country with enough money to buy FIFA, the most corrupt sports organization in the world. “They just don’t care,” Grant wrote about leaders of Qatar and FIFA. I read Grant’s posts from Qatar, on the personal website he was building after leaving Sports Illustrated during the ongoing pandemic. He was offering his experience and courage for paid subscriptions, but also made some free essays available. He was no home-bound typist – known as an Underwear Guy -- pecking away on a laptop. Grant Wahl was out there, fully credentialed, with the respect of the soccer community, and also with the eyes of the Qatar security force on him. In a very real sense, he was a lone wolf, existing on his own guts, his own instincts, his own strength, in a FIFA/Qatar environment that had no reason to like what he was typing. As soon as I heard about Grant’s death, I had a pang of déjà vu. I was also 48 during the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, a country I love, traveling to modern and hospitable cities, hundreds of miles apart. I stubbornly continued to jog at high altitude, taking in the bad air. After a few weeks, I was shot. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t move. Couldn’t think. Couldn’t type. Fortunately, my wife was with me, to witness that I was running down. I also had something Grant Wahl did not have these days – a home office. I called the NYT sports department and said I was dragging, and needed a day or three off, but my editors, my friends, Joe Vecchione and Lawrie Mifflin, agreed that I had another great assignment, the Goodwill Games in Moscow, coming up, and I needed to be strong for that. My editors told me to come home, see my doctor, and determine if I was strong enough to go back out to Moscow – which I was. One of the best assignments I’ve ever had. (Plus, my wife was with me, buying fresh vegetables and fruit at a farmer’s market in a nearby square.) I also had editors watching my back, whether as a news reporter or a sports columnist. To this day, even as a typist for my own Little Therapy Website, I consider every word, every opinion, from the vantage point of the great editors, who found mistakes, even reined me in sometimes, much as I griped. Journalism has its dangers. I’ve been sent to riots and shootouts and assassinations and coal-mine disasters where I had to be quick on my feet, but nothing like colleagues currently in brave, admirable Ukraine. Sometimes, “even in sports,” the hours, the travel, the diet, the microbes in crowds, can beat you down. We will learn more. What we know now is that Grant Wahl was doing his work, writing so well about a subject he loved, and he has passed, way too young. In the midnight hour on a murky Saturday night in late October of 1986, Shea Stadium was going mad.

A squiggly grounder by Mookie Wilson had somehow kept the Red Sox from winning the World Series that night – and fans were screaming, and nearly a dozen New York Times writers were pounding away at their laptops, shouting into phones, bustling noisily to update their early stories for the last print deadline of the evening. Enlightened cacophony. The sports editor, Joseph J. Vecchione, sitting behind us in the pressbox, was coordinating with the staff in the office, making dozens of decisions, on the spot. Then it was over. We had gotten it done, on deadline. A young Times news reporter, doing spot duty to cover fan madness, police activity, etc., watched the sportswriters (so often maligned as “the toy department”) do their jobs. When things quieted down, the young reporter said casually to the sports editor, “Wow, that was impressive,” or words to that effect. And Joe Vecchione said drily: “We do it every day.” If Joe had added, “Kid,” he would have sounded just like Clint Eastwood in “The Unforgiven.” That professional pride epitomized Joe Vecchione, my friend and advisor in my early days of writing the sports column. Joe passed Friday evening at 85, after years of suffering from Lewy body disease, cared for by his wife, Elizabeth, a wise and devoted nurse. They are parents of Elissa Vecchione Scott and Andrea Vecchione, with three grandchildren: Joe’s aura of family man was clear to people around him. He was a boss with values. I got to know him as a terse, decisive voice on the phone, in the 70’s, when he was an editor in the photo department, and I was a news reporter. Sometimes I was at breaking news and I had to coordinate with the photo editors. Joe was authoritative and efficient. Then he was plucked by Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Gelb to help form the new SportsMonday section, and he was there in 1980 when sports editor LeAnne Schreiber recruited me to be a reporter, filling in for Red Smith or Dave Anderson here and there. When LeAnne moved on, Joe became sports editor, and when Smith died in 1982, it was Abe Rosenthal’s decision to hire a new columnist, and it turned out to be me. Here is where the kindness and shrewdness of Joe Vecchione took over. I had been conditioned by 10 years as a Times news reporter, to keep any trace of myself out of the copy. Give sources. Quote authorities. No opinions. That was the old, gray NYT – and I was one of the foot soldiers, thoroughly indoctrinated. As a columnist, I knew the subject matter, and could write and report, but I was trying too hard to find a voice, hinting at my opinions. I was being too cute. Joe had some advice (and I paraphrase:) “Be yourself. Tell us what you think. People want to know how you feel, what you know, what is right and wrong. Don’t hold back. This is the way things are going these days. You have freedom.” He removed a decade of thoroughly valid reportorial rules, freeing me up to be a columnist. Joe also had an instinct for hiring and enabling good people, hiring columnists Ira Berkow and Bill Rhoden, relying on deputy editors like Bill Brink and Lawrie Mifflin, and he backed up his columnists. I benefited from this in 1990, when I was writing columns from the World Cup of soccer, held in Italy. The young American team, in its first appearance in 40 years, managed a taut 1-0 loss to the Italian team – a huge accomplishment. But I pointed out that Italy did not have great strikers – that is, players gaited to score goals from up close – and I wrote this was because their great national league imported scorers from Germany and Argentina and Brazil. I wrote: “The home-grown players do not develop the knack of scoring. Mussolini once lamented that his was a nation of waiters. It is not stretching the truth to say that Italy is currently a nation of midfielders.” The next day, the sports department got a call from an Italian-American reader who felt using the remark attributed to Mussolini was prejudicial. (Fact is, I love Italy and root for the Azzurri, except when they play the U.S.) The person in the office, taking the call, told the reader that the sports editor was okay with my comment. And who is the sports editor? “Joseph J. Vecchione.” That pretty much ended the conversation. Joe could be tough, and he had to make a lot of decisions. I once was whining in the office about something or other, and Lawrie Mifflin, the deputy sports editor and loyal friend of Joe’s and mine, told me, in effect, “You have no idea how much he has to handle every day” – including complaints from leagues, teams, player unions, sponsors, agents, public officials, fans, to say nothing of staff members. In Joe’s regime, we let it fly, and Joe fielded the complaints, kept most of it from our ears. Joe was sports editor for a decade, then moved back into the mainstream of the paper. He retired at 65 and the editors promptly brought him back to help the transition to the new building a few blocks away. Over the years, I was impressed by the masthead names, the serious people (some of whom condescended to sports personnel), who were his social friends. They trusted him – for core values, like honesty, like thoughtfulness, like culture. That is no small statement about a Times official, my friend, who helped move the sports department into the future. (Any insights/anecdotes about Joe? Please add them in Comments, below.)  Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, Jamaica ’56 and Hofstra ’60, passed on June 10. He had turned 83 on June 1, and had been in failing health for months, lovingly cared for by his wife, Roberta. This is a hard one for me to put together because Stan and I were in the same school for nine straight years -- Halsey Junior High and Jamaica High in Queens, then Hofstra College in Hempstead. Then Stan went to dental school and served as a dentist as a captain in the Army at Fort Lewis, Wash., and settled into his practice in New Hyde Park, marrying Roberta Atkins, helping her with their two children, driving around to dog shows all over the place, in with their English Mastiffs -- a big guy showcasing his big pets. We became much closer in the past two decades, as old Hofstra basketball and baseball guys (and one aging student publicist) got together at Foley’s in NYC. I would drive into the city and back, sometimes with other front-liners, Donald Laux and Ted Jackson. Basketball was our common denominator. Stan had a great souvenir of his season as a 16-year-old senior on the Jamaica varsity -- a scar on his forehead, from the city tournament in the old Madison Square Garden when he was hammered by Tommy Davis of Boys High. When Tommy became a star with the LA Dodgers, I would remind him that an endodontist on Long Island was looking to get him back.  Stanley in 59-60 season. Stanley in 59-60 season. I was at courtside on a sleepy January afternoon in 1960 when Hofstra lost on a long basket by Wagner at the buzzer. It turned out to be the only loss in a wonderful season – 23-and-1, but not good enough to get into a post-season tournament. Half a century later, we caught up with the villain who had beaten Hofstra with that long jump shot – Bob Larsen and a couple of teammates met a few old Hofstra guys at Foley’s, and I wrote about that in the Times., https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/sports/ncaabasketball/52-years-later-recalling-a-shot-that-sank-a-season.html In our old age, basketball was the link. Stanley had two season tickets at the Hofstra gym, right above the scorer’s table, and sometimes he would invite me. He became friendly with the coaches, first with Mo Cassara, then with Joe Mihalich, two basketball lifers who loved our old stories about the memorable coach, Butch van Breda Kolff, the old Knick. (Crude and also insightful, Butch was oddly formal, often calling his players by their full first names—Donald, Curtis, Stanley. As the publicist, I was “Grantland.”) Every October, Joe would invite us to a practice, let us sit behind the basket, give us frank insider critiques of his team. He called Stanley “Doc.” For one afternoon, my guys were part of the team, part of the school, again. I remember at one October practice, the star of the team, a shooting guard at 6-foot-3, also from Queens, was chatting with us, and was politely bemused that Stanley was the star rebounder at the same height. (I wrote about those sweet annual visits to our alma mater.) https://nationalsportsmedia.org/news/my-alma-mater-thrills-some-old-players- Just before the pandemic, Stan stopped getting around, because of Parkinson’s disease and other problems. We would talk on the phone and he would talk about Roberta’s art work and how well she took care of him…and proudly about their family: son, Harry, who had taken over the endodontist practice, (“better hands than me”) and his wife Macha and their children, Max and Remy, and Stan and Roberta's daughter, Margaret Morse, and her husband Richard and their children, Olivia and Henry. He always knew what they were doing. When I visited them last week, Roberta was masterfully managing a hospice operation. (I never heard him complain about his bad breaks with health, and he was always upbeat about the home care from aides like Kenia.) We sat by his hospital bed and we talked about the old days and our dwindling Hofstra guys, and his Yankees and his Rangers….and I praised how inclusive he was about his basketball world. This is what I told him: A decade ago, my wife and I were visiting our friends, Maury Mandel and Ina Selden up in the Berkshires, and Maury’s kid brother Joe and his wife Jean were also there. I suddenly blurted to the younger brother, ”Hey, I know you – from junior high school.” Turned out, Joe had been in the same class as Stanley – and had played on the same class team (Stanley was also on the school team.) I ostentatiously pulled out my cellphone and called Stanley: “I got Joe Mandel here, from Halsey.” They started chatting, more than six decades later, and Stanley told him, “You were a good point guard on our class team.” As any old schoolyard player knows, there is no higher compliment than being praised by a college star. Generous guy, Stanley. Then they started talking about the girls in their class. We continued that conversation the other day -- basketball and girls in our grade -- and for a few minutes, it was very nice to be 13 again. ** (It's so nice to see comments or emails to me, from old friends. Ken Iscol from junior high. Jean White Grenning and Wally Schwartz from Jamaica. A lot of the Foley's gang. Just to drop a few names. Roberta (I knew her brother, Jerry Atkins -- in grade school!) has held things together, admirably. The funeral is Monday at 11:30 AM at Beth David Cemetery, 300 Elmont Rd., Elmont, N.Y. 11003.) For the moment, please feel free to remember Stanley…and say hello to Roberta and the family… here…. They are monitoring the lovely comments here on this site. Thanks. GV Ever since Roger Angell passed last week, friends have been e-mailing about how great he was, and asking how well I knew him.

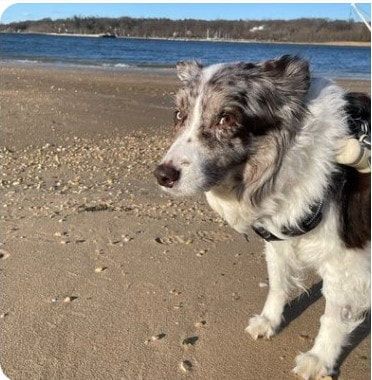

Let me say, he was grand company in a pressbox watching a game. I always thought he seemed liberated by his mid-life discovery, his strange hobby, writing about baseball. It began as his left-brain, right-brain activity, when he wasn’t editing temperamental fiction writers or conducting in-house business at the New Yorker or dealing with the vicissitudes of life. He enjoyed the hell out of this other world, and it showed. He also loved paddling his kayak or sailing along the Maine coast when he wasn’t writing about Pete Rose or Reggie Jackson or the baseball denizens of the Pink Poodle, his hangout in Arizona during spring training, or editing what any sportswriter would respectfully call “real writers.” Now and then, he would pop into Yankee Stadium or the Mets’ ballpark, without the weary pack-mule trudge of the beat writer or old-fashioned sports columnist (been there, done that) lugging a laptop, expected to produce profundity on deadline, halfway through the season, 81 up, 81 to go, plus the endless autumn trek. As we all said in our alibis for why we were not Roger Angell: we had deadlines. While we were pecking away, he could hang back and chat up a ball player who grasped that this older guy knew the game and was not looking for a few quick quotes. I admired the working friendship he developed with, let’s say, Dan Quisenberry, a submarine-style relief pitcher with the Kansas City Royals, who was cool enough to explain his technique. Roger also took seriously the first female writers in the press box and – gasp – the locker room, who were professionals, just like men, if you can imagine. So, how well did I know him? I got off to a dumb-ass start. It must have been 1968 when I sat next to a guy near 50 and we introduced ourselves and he said something about “New York” and I thought he meant the new weekly magazine so I wished him luck with the new publication. To his credit, he did not correct me, nor did he back away from this dolt. Later I deduced that he wrote for the New Yorker and began subscribing, not just for his occasional baseball pieces but for the great eclectic literacy of the magazine. I still subscribe to the New Yorker in the age of Editor David Remnick – a great guy who started as a daily sportswriter, for goodness’ sakes. The arrival of the New Yorker—the print version – is a highlight of this pensioner’s life. Did I learn anything from Roger Angell? The best part was the way he thought independently and observed the sub-marginal things and had the time and space and license to elaborate. Plus, he had talent -- could play with themes and details, knowing exactly what he was doing. He was a model, but then again, in our collective world, no journalist should lack for models. My parents were journalists and I came along in the pioneer Newsday sports department in the 60s, with crusty old editors and the new breed of chattering younger types, known as Chipmunks. And then there were books that made me want to write longer and better. In the early 60s, I sought out “Bull Fever” by Kenneth Tynan, a London drama critic who roamed to the corridas of Spain, or “Cars at Speed,” by Robert Daley (son of the noted Times columnist, Arthur Daley), who had bolted to Europe to write about the Grand Prix – and life in the old world – and ignited my wanderlust. In the same period, I read “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” by Harry Caudill, a lawyer from an old Kentucky family, whose lament for the defaced mountains made me want to go to Appalachia and see what was left. So many great writers, out and about, dealing with current issues, from their heart, from their eyes, from their brains, writing at entertaining length. Over the decades, I was always happy to spot Roger Angell in the press box. I cannot remember what we talked about, but it was fun. When I retired at the end of 2011, I kept up by phone when I particularly loved something he had written, and I called when he had a death in the family. When my wife and I started visiting her elderly uncle in coastal Maine, I called to tell Roger how much we loved his other world. My wife says I should have told him that some Angells popped up in her sprawling family tree from New England in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Finally, a confession: Every year, readers would look for Roger’s annual Christmas poem, hailing and pairing people with exotic and yet topical names. For decades, every December, I scanned the poem for my name, but it never appeared. I never told him how sad I was. Other than that, Roger Angell was, just as you imagined, great company as well as great reading. * * * In case you missed: Obit by Dwight Garner: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/sports/roger-angell-dead.html Tyler Kepner’s appreciation: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/23/sports/baseball/roger-angell.html And a labor-of-love sampling of Roger’s work, from Lonnie Shalton, lawyer in Kansas City and a true lover of baseball: http://lonniesjukebox.com/hot-stove-192/ I called her Pretty Girl whenever she sat by my side. She must have known I was smitten, because she let me pet her and talk to her even if her immediate family members were right there. She was a Blue Merle Australian Shepherd, a highly desirable breed, tooled to chase sheep up a steep incline, sorting out dawdlers. She could muster her speed and power when let loose in safe terrain but she was gentle and domesticated in Dave and Joelle’s house, near us. She had beautiful color and soft hair and a sleek face. She could have been a model.  Max Scherzer Max Scherzer She was named Blue, for her right eye, alongside her darker left eye. Exactly -- just like Max Scherzer, the traveling pitching star, currently with the Mets. When I see Scherzer blowing hitters away, I think of Blue. (The web says 5 per cent of Blue Merle Australian Shepherds have one blue eye, a genetic variant.) (The web also says a small percentage of humans has one blue eye, from a common ancestor 6-10,000 years ago.) I never saw Blue show a temper, even when Isabel’s cat or Greta’s cat sauntered by. Blue tolerated the felines, shared food space and floor space. She was beautiful; she had nothing to prove. I am not a dog person (and my wife has major dog allergies), but I did love our highly neurotic and foul-smelling cocker spaniel named Ebony, adopted while I was out of town, and good sport that I am, I walked her and washed her, and in turn she cuddled at my feet when I was reading or napping. I always referred to her as “my last dog,” but I still get sad when I think about her (and think I smell her, two decades later) whenever I lie down on my couch for a nap. Most of my family loves dogs. My mother adored Taffy, whom she walked for exercise while gallantly fighting back Multiple Sclerosis, and my sister Janet and brother Peter both have dogs these days. Laura and Diane had Griffey, a springer spaniel who could haul driftwood out of heavy surf north of Seattle. When Laura was a sports columnist out there, she knew and liked Ken Jr., who asked why she named her dog Griffey. “Annoying….and cute,” she said, and Ken seemed okay with that. More recently, they had a little Lhasa Maltese mix, whom I nicknamed The Yapper, in homage to Donnie Iris and the Jaggerz and their hit song, “The Rapper:” The Yapper used to snap and snarl at me, even when I was feeding her or taking her for a walk. But as she got older and wiser, she sat at my feet and let me pet her. Peter and Corinna had Ginger, an English bred Yellow Lab whom Corinna took for long pre-dawn walks in the neighborhood, and when Ginger was fading, she was replaced by Finnbar Octavian, whom they also love. David and Joelle adopted Blue 10 years ago from the great North Shore Animal League, near us in Port Washington. She was said to be six months old, but maybe she was older, because she was so mature. In her first years, Blue had the energy of a teen-ager. We’d go in the back yard and I would boot a soft soccer ball into a far corner. and she’d bolt to get it, as if it were a wayward sheep. A couple of years ago, I sent a ball into a corner and she gave me a baleful look, one blue eye and one dark eye, as if to say, “Uh, I don’t do that stuff anymore.” Either way, she was still beautiful. A month or two ago, she stopped eating much, and began losing weight and her coat became splotchy and she mostly sat and watched. Her family sought good veterinary care, and the verdict was stomach cancer. While Blue could still get around, David took her to Bar Beach, where she loved to romp at low tide, and Dave posted it on Twitter. I came by to hug her one more time, and on Friday family members received a photo from Dave, of an empty collar with the name "Blue" on it. Marianne wrote: "She’s running up the mountain, free again. ❤ to her, on her way." Speaking of hills to climb again, may I offer this song, by Alice Gerrard, sung by Kathy Mattea.

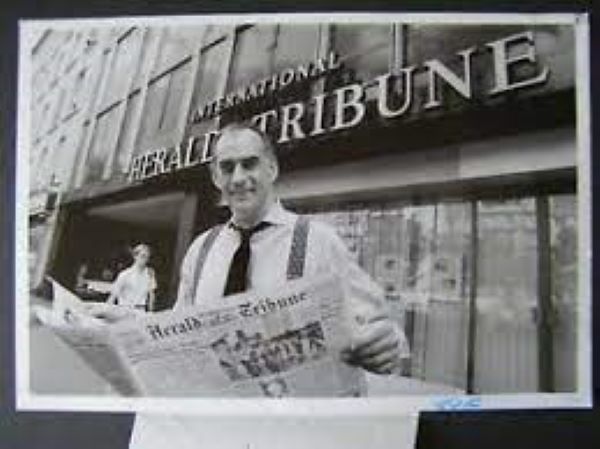

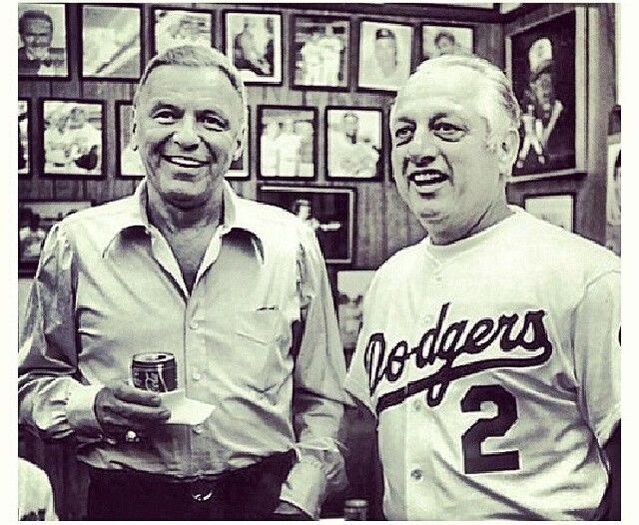

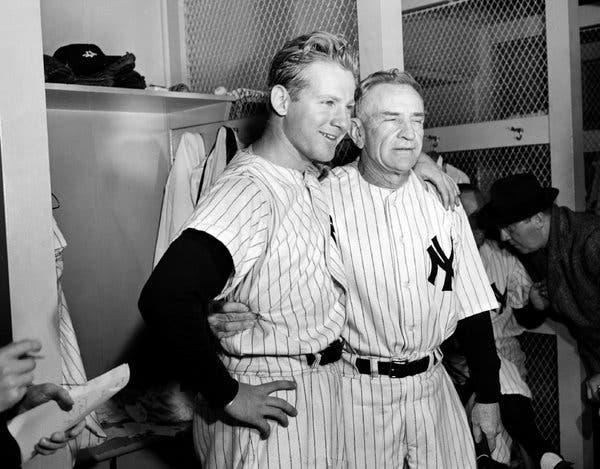

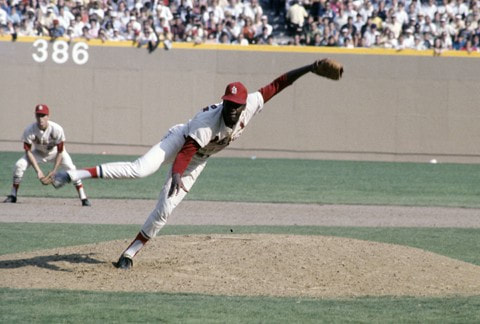

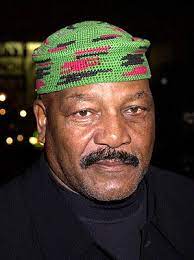

For Blue: "Agate Hill." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Adm_rbwCZJU (This is one of those pieces I hate to write, but am compelled to do.) It was March in 1953 and I bumped into John Vinocur in the GG subway, the local that ran underneath Queens Blvd. John was a year behind me in Junior High 157 but we had gotten to know each other on the daily ride to Rego Park. The headlines in the papers – everybody read a paper in those days – The Daily News! The Times! The Trib! The Mirror! – and these were just the AM papers -- were about the death of Joseph Stalin on March 5. The question was, would the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S. be lessened or heightened by whoever came next, a fun discussion in any decade. John was a news junkie and so was I and we chatted animatedly, and no doubt loudly and ostentatiously, until the GG local had arrived at our stop. I thought of that subway ride when I read that John passed Sunday in Amsterdam, yet another great city he knew from his time as reporter and editor at the Associated Press, International Herald Tribune, New York Times and Wall Street Journal. He lived the dream that was perhaps in our brash Queens minds on that March morning of 1953. The obituaries tell of his accomplishments and hint at his bluster. I know somebody who worked in the Paris office of the IHT for a year in the early 80s – “dashing and vibrant” were the words she used. That was when the IHT was an eccentric wing of the Times, its office never far from the Champs Elysées, its product a must-read for ex-pat or vacationing Americans, long before the Internet. News from home! Sports scores! It was the offshoot of the paper being hawked by Jean Seberg – “New York Herald Tribune!" – in Paris, as Jean-Paul Belmondo sharks her, in the 1960 movie “Breathless.” That was the same world sought out by John Vinocur, who had played a little basketball at Forest Hills High, went to Oberlin, and then off to France, where he played semi-pro basketball. The hoops were part of his rep, and he often mentioned it to me, knowing I would be properly impressed. At some point, John went to work for the Associated Press in Paris, earning good assignments like the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. Here is eager young John Vinocur, covering the massacre of Israeli athletes, described by another deceased pal of mine, Hubert Mizell, late of the St. Petersburg Times. "A native New Yorker, he… matriculated to backwater France, learning the language from natives and picking up money playing semi-pro hoops.” Hubert then describes how John “ignored police warnings and scaled a fence to get close to Building 31.” That would be John from Queens, scaling a fence. I can find no reference in his obit to how John got his job at the Times, but as I recall it, John was working for the AP in Paris when the movie “Last Tango in Paris” came out, portraying the club world of Paris in all its seediness, and John went to one of the raunchier clubs and wrote about it, and somebody at the NYT noticed. That’s how it worked: somebody likes your clips. John worked in the home office of the NYT for a while but my guess is he was used to being The American in Paris, so he went back. We ran into each other over the years, and would share opinions of New York sports, our Queens voices the loudest in any brasserie or café, still bonded from the GG local subway. *** If you can leap the paywall, you can find Sam Roberts’ obituary of John Vinocur here: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/06/obituaries/john-vinocur-dead.html *** And just to get a feel of the dream, Paris in the 60s, here is the clip from “Breathless:” Henry Aaron. Tommy Lasorda. Jim (Mudcat) Grant. Poring over the magnificent two-page spread in the Times, honoring prominent people who passed in 2021, I realized I could write reams about stars I knew from the locker rooms. I could also recall famous people I met here and there – Colin Powell, streetwise New Yorker ---- Vartan Gregorian, kind Armenian wise man -- and Larry Flynt, seedy champion of pornography, who happened to be a hilarious and incisive interview. But my heart, at year’s end, is remembering relatives and friends I got to know up close, who have left a personal gap. As Arthur Miller wrote: Attention must be paid. Aunt Lila. She was my wife’s aunt – helped raise her -- but she also became my aunt, jolly and chubby with a beautiful smile and a generous hug, over the decades, sidling up to me and asking about our children, our work (she had an admirable curiosity), and whether I knew the Lord. Her children and grandchildren cared for her in old age, shuttling her from northeast Connecticut to suburban Long Island, keeping her going, medically and socially. At a reunion last summer at a daughter’s home, Aunt Lila was wan, low on energy, and Marianne sat by her all afternoon, sensing this might be the last time, which it turned out to be. But Aunt Lila’s smiles and hugs and kind acceptance linger on. Captain Curt. Once a point guard on very good basketball teams at Hofstra, Curt Block became a publicist at NBC and had other memorable gigs. (As a young reporter, he interviewed young Cassius Clay, and had the presence of mind to keep the rudimentary tape, re-discovering it in old age.) When aging baseball and basketball players (and one scribe, me) began to meet periodically at Shaun Clancy’s great place, Foley’s, Curt took the slow train up from Philadelphia and became the greeter, the treasurer, the captain, sitting in the middle, enjoying everybody else’s stories, moving the ball around, as he had against Hofstra’s opponents, back in the day. He quietly alluded to impending heart surgery, and last summer he went to sleep and did not get up. Because of the pandemic, the old boys have not been able to meet since, to uniformly mourn our quiet leader. Neighbor and Nurse. Ann Schroeder was a nurse in the Bath-Brunswick area of Maine. She got to know my wife’s Uncle Harold (older brother of Aunt Lila) and she became a volunteer guide to his old-age miseries. We got to know her through her detailed emails, explaining Harold’s health problems, what was being done, so we could assure his relatives that he was surrounded by skilled, loving friends in that wonderful area that has become our own sentimental home. After Harold passed, we stayed in touch – via health newsletters Ann sent. She casually alluded to her own breathing issues, and last summer she noted that she was now on hospice, and then the e-mails stopped. In keeping with this understated woman, her service was private.