|

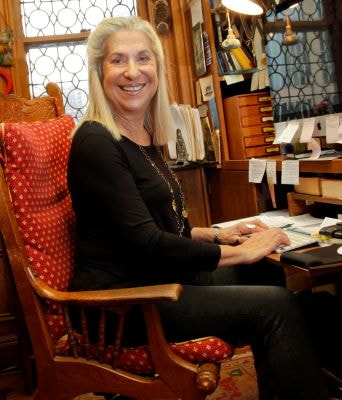

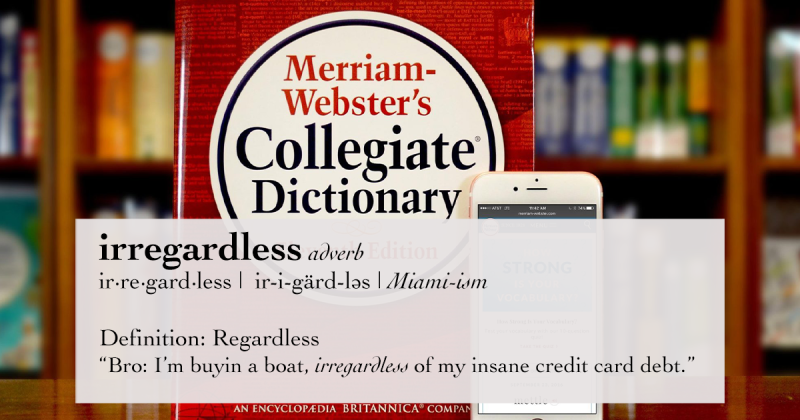

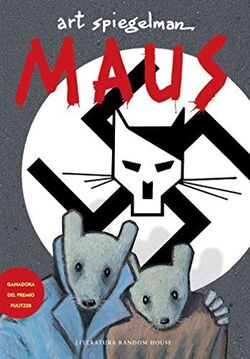

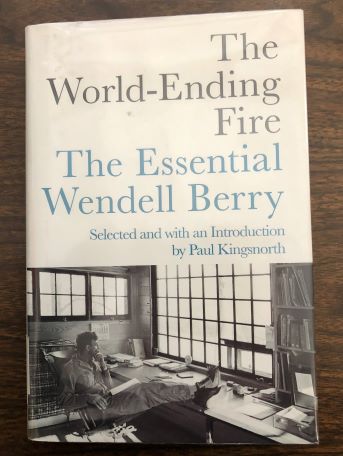

Whenever these three great articles were -- imagined? assigned? written? spawned? -- could writer or editor have imagined them materializing on one Thanksgiving weekend screaming for a coda of peaceful and gratifying reading? This is exactly what happened to this reader, after a lovely run of children, spouses, grandchildren and friends. I settled down for a quiet morning of going through The Times and the New Yorker and came away with enough depressing news, well handled, but also found three lengthy articles that demanded full attention. All three articles are written by women, about singular women, whose work has captivated me over the years. (I recognize not everybody can get over the paywall of these two great publications, but many can qualify for X number of freebies per month. I urge you to try. Meantime, here is my enthusiastic summation.) Everybody Knows Flo From Progressive. Who is Stephanie Courtney? By Caity Weaver in the NYT Sunday Magazine I was a Flo fan the first time she emerged on the television, wearing her white outfit and a knowing smile, maybe even a wink. She was selling Progressive Insurance – I tend to forget brand names from commercials – but she was also selling herself. I’m in control. I know stuff. Some of her best work was done in the presence of men and motorcycles. (obviously to appeal to motorcycle drivers, which I am not, but I admire people who va-room on the open road.) Flo (I have to be reminded that her name is Stephanie Courtney) reminded me of one of the great bits in the movie “Something Wild,” when bad-girl Melanie Griffith utters something lewd to a motorcycle cop (the writer-director-actor, John Sayles.) Okay, Flo caught my “attention,” and I became a fan of the commercials, including the three sidekicks (mentioned in the NYT but not named) – a goofy guy, a whiny woman, and a stable brother. They mostly play off Flo, as she makes snarky comments off in a corner, and all are welcome in a world of annoying commercials. Writer Caity Weaver goes light on biographical material but provides heartwarming description of how this comedy-club also-ran improvised her way into what seems to be a fortune. (check out the caviar anecdote.) For anybody curious about how films/commercials are done, Weaver also provides lavish info on a shoot in a frequently-used home in the LA region – lights and electric cords and snacks for the workers. I have a friend who rents her house near the beach for TV shoots. I know more than I did about this world. But basically, I also know more about the now-rich woman with the knowing smile who can materialize on my screen any time she wants. *** https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/11/27/a-friend-died-with-her-novel-unfinished-could-i-realize-her-vision The New Yorker materializes in most weeks, and also pops up on the Web, with experts and timely reporting from hideous parts of the world (Hamas, Trump, climate, etc.) The magazine has morphed from a fey weekly to a daily e-necessity, under the guidance of David Remnick, a friend from sportswriting days (tapas in Barcelona during the 1992 Olympics), later a reporter in Moscow, and now a most obviously un-Ross, un-Shawn editor of the New Yorker. Congratulations, David. The Nov. 27 issue materialized with the cover depicting eight folks around an urban apartment dining room (view of the Empire State Building behind the celebrants) eight glittering color screens amid the remains of turkey, wine, candles. “That’s me!” blurted our grand-daughter, Anjali, who on Thanksgiving took part in a memorable dinner for 17 – 17! – prepared by two adults with very demanding jobs. The elder table had a lot of talking. The younger table materialized into the New Yorker cover of one of the best editions, ever, if you ask me (Zadie Smith! David Sedaris! Roz Chast!) One captivating article “Ghost, Writer,” was by Leslie Jamison, a writer who was asked by her dying friend, Rebecca Godfrey, to complete a copious fictional biography of the art doyenne, Peggy Guggenheim. Godfrey leaving left specific instructions and references for Jamison, challenging her to convert them, including a Rosebud cluster of final words. The book aside, Jamison surely immortalizes her dead friend, also giving a sketch of a real biographer at full tilt.  Photo, Nicholas Calcott, 2023. Brooklyn Museum. Photo, Nicholas Calcott, 2023. Brooklyn Museum. Just before the Jamison article is: Joyce Carol Oates’s Relentless, Prolific Search for a Self by Rachel Aviv I knew I would be fascinated by the article because I once was fascinated by Joyce Carol Oates herself, in a brunch interview (me, of her.) Oates had just issued a book about boxing and I was writing a sports column for the NYT (remember sports columns in the NYT? This is what they were like.) https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/04/sports/sports-of-the-times-a-heavy-weight-looks-at-boxing.html?unlocked_article_code=1.BU0.3IKu.2xDusXfh_jjr&smid=url-share Oates was fascinated by boxing. I love boxers…but I hate boxing, what it does to people’s brains. We sparred over coffee and bagels, or whatever, and I was sorry when the interview ended. Since then, I have toyed with the NYT book review staple in which writers are asked what three writers they would invite for dinner. A lot of writers, being writers, mooch a fourth guest. Nobody is ever going to ask me that question for the Book Review but I have my answer prepared: William Shakespeare (what about that painting in the National Portrait Gallery?), Jesus Christ (not a writer, perhaps, but a Jewish preacher), Thomas Wolfe (who taught me to read, and think, and care) and Joyce Carol Oates because…well, because. Oates was complicated, and she remains complicated in the lengthy “Personal Statement” by Rachel Aviv in the current New Yorker. I’m not even going to try to summarize. I just know I read every word, and urge others to do the same. *** Note: I just glanced again at the New Yorker’s table of contents. Barbra Streisand’s book, by Rachel Syme. A book review by Thomas Mallon. An essay by Hilton Als. A review of the Bernstein movie, by Anthony Lane. Still a few hours left for reading at the end of the Thanksgiving holiday. One of the many great things from The New York Times recently has been a canvass of 17 – count ‘em, 17 - opinion columnists of a cultural icon that best exemplifies the United States. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/06/20/opinion/nyt-columnists-culture.html After perusing the list, my first reaction was how many Times opinion writers chose highly accessible television series – many of which I have never seen. Please, this is not a value judgment. We all need entertainment/stimulation that is more enjoyment and less work. I’m likely to be watching the Mets – my patience with these poor slumping mugs is not endless – and coming soon, the Women’s World Cup of soccer, a quadrennial delight. And I spend way too much time gaping at the Bureau of Wishful Thinking, hoping for a few guilty verdicts, and soon. The NYT’s feature demonstrates that many of its best and the brightest commentators have a life, which helps them understand this vast and divided country as well as relax and enjoy. I was tantalized by all 17 choices, but a few that stuck with me that most: ---Bret Stephens got me by picking the film “Pulp Fiction.” Sometimes, just for fun, I go fishing on Youtube for the last 20 minutes or so, starting with Harvey Keitel as Winston Wolf a mob fixit man wearing a tux who cleans up a very messy murder scene. The movie ends with John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson as two gunslingers who foil a hapless couple trying to stick up a diner. I don’t know if that segment is about America or rather about LA a very distant generation ago but either way I love it. ---David Brooks wrote: “I nominate Blind Willie Johnson’s 1927 rendition of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” Brooks added: “Johnson is playing his slide guitar in a way you’ve never quite heard a guitar played, and he is not really singing so much as humming, groaning and intoning. There are few words, just verbal renderings of woe.” ---Nick Kristof wrote: Horatio Alger’s “first blockbuster novel, published in 1867 as a serial, was ‘Ragged Dick.’ Its hero is a 14-year-old shoeshine boy who sleeps on the streets of New York City. While Dick is illiterate and likes to gamble, he has a good heart, a willingness to work hard and a strong sense of honesty.” This being my personal therapy website, I came up with my own quirky visions of America: --- “The Sopranos” – the only series I have watched in the last 40 years. Not just for Tony and Carmela but also the Italian hitman Fiorio (“Mr. Williams") muscling the smug golfing doctor into the water hole or the cool one-legged Russian woman who dumps Tony. I still ponder what the final episode meant. --- For novels about America, I could choose Mark Twain, but I will stick with Thomas Wolfe, who taught me how to read and feel as a teen-ager. Most of his books are based in Asheville, N.C., but I would nominate “O Lost,” a revision of “Look Homeward Angel,” with the first section (inexcusably excised by the original editor) about of a teen-ager standing on the highway south of Harrisburg, sassing Confederate soldiers as they march toward Gettysburg, summer of 1863. That boy will become Thomas Wolfe’s father in North Carolina. The fissure in the United States that summery day is as real as today’s news. ---Every Thanksgiving, our son David plays the classic Scorsese film, “The Last Waltz,” the final concert of The Band – four Canadians and Levon Helm from Arkansas, with guests as diverse as Muddy Waters, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Emmylou Harris, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, the Staples Singers, Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan, singing “Forever Young.” However, if I have to choose one icon that catches America, I will go classical. I think of the long flights I used to take, over the Great Lakes or the Rockies in daylight, or the reverse flights, heading home in the midnight hours, the twinkling necklaces of highway, lone cars, small towns, rivers, so much space, so much promise, so much beauty, from 30,000 feet. Then I think of the composer from Bohemia, somehow getting himself to deepest Spillville, Iowa, feeling the vast space, hearing America’s great asset, the spirituals and the soulfulness of the Blacks, and how Antonin Dvorak put it together in “Symphony No. 9 --From the New World." (And if I have a choice, conducted by, himself an icon, Leonard Bernstein): Your choices/suggestions/comments?

Oy, it’s back – the theme of Donald Trump as prototypical Queens lout.

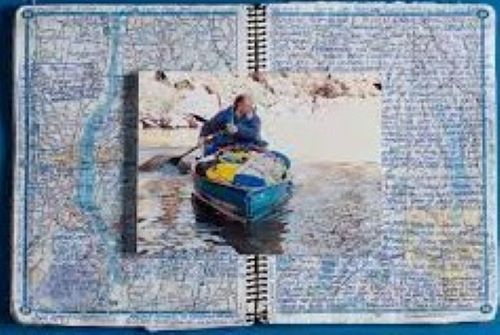

I gather this from this Sunday’s NYT, a review by Joe Klein of a new book by Maggie Haberman, both of whom I admire greatly. But somehow the lumpen masses of Queens County are still being connected with the disturbed, amoral thug who has terrorized the U.S. and the world since 2016. As it happens, I grew up on a busy street, about half a mile from the Trumps to the west and the Cuomos to the east. Many of my friends went to grade school with Freddie Trump, older brother of Donald, and say good things about him. But in the big picture, nobody is typical of Queens, which ranged from ethnic western Queens to the remaining open spaces of eastern Queens. In the middle was Jamaica High, one of the best schools in the city. (Nasty little Donald was sent off to private schools, where, theoretically, money would buy protection if not character uplifting.) Was central Queens to blame for the criminal tendencies of Donald J. Trump? That premise annoys me because I could name dozens of friends and acquaintances who worked for success in more socially-acceptable ways. I will name only a few – Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who grew up a block of so from the Trumps, who came through a hard childhood to become a major voice in feminism and journalism (Letty has a new book), and Steven Jay Gould, a grade or two younger than me, who became a major scientist. Nowadays, I follow the very public activity of two other Jamaica grads -- Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee from Yale, representing an urban ward in Houston, and Jelani Cobb from Howard, a bad right fielder for Jamaica (he says) but a terrific journalist and professor. I submit that the striving ethos of Queens produced those four above, and thousands more, beyond the larcenous Trumps. From our little chunk of Queens in mid-to-late-‘50s: the professor and NASA scientist, two civic activists from Jamaica Estates, our Class President-for-Life who has been air-lifted into Alaska in the winter to serve as teacher and community volunteer, and several judges, including one long settled in Washington State. I could tell you about my Black pal in the Jamaica chorus who had to lobby against being stereotyped into vocational classes, and now has a doctorate and a career in a government agency. (We sang the school song at his recent Significant Birthday celebration.) I could tell you about the Cleftones, who sang under-the-streetlights doo-wop harmony for decades. Then there was the Holocaust survivor who played soccer at Jamaica and became a doctor out west. We had five doctors on the Jamaica soccer team. One could also sing. One became a med-school dean. One has been working at a Queens hospital in the worst of the Covid pandemic. And speaking of doctors, one of the wittiest and smartest kids in Jamaica Estates graduated from college and then realized she could have become a doctor – and she did, years later, and has had an admirable career. Two guys in the same radio-journalism class with me turned out to be well-known political activists for decades. And another teammate (a doctor) and his kid sister (an academic) lived next door to the Trumps for a while. She remembers how her ball would bounce into the Trump yard and Terrible Little Donald, 4 or 5, would pounce on it and say, “It’s in my yard. It belongs to me.” Kind of like classified government papers, you might say. By the way, the drive to excellence was not just a Jamaica High phenomenon. At nearby Forest Hills High, the star jump-shooter, Stephen Dunn, played at Hofstra and became a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet. At Van Buren High, which sprung up in our eastern neighborhoods, a future lawyer, Alan Taxerman (the late and lamented Big Al to readers of this site), was sure he was the smartest kid in the universe, until he noticed that Frank Wilczek actually was. (Wilczek later won the Nobel Prize in physics – see Van Buren’s hall of fame.) And then there were Central-Queens people who went into business, education, government, law, library work. Was there something in the air or the water of Central Queens that led thousands of us to socially-acceptable lives? Joe Klein – again, a long-admired colleague – mentions elders making snide references to other ethnic groups. Were we all Archie Bunkers? I ask this because my household was a meeting place of the Discussion Group, organized by two upwardly-bound subway motormen, one white, one Black, kept at 50-50 ratio, comprised, by definition, of Queens bootstrappers with ideals. My brother Peter recalls being a little kid, sitting at the top of the stairs, listening to loud voices and loud opinions -- but then refreshments would be served and voices would soften, laughter would commence. It was a lesson for the next generation. You could care – and you could get along. What was the motivation for we rustics out there in Queens? Were we different from kids in “The City” A friend of mine was running with a fast little group from Manhattan, and I tagged along, impressed by how they knew the music clubs and museums and parks of Manhattan. (One of our new friends, a very nice girl named Gloria, actually lived on Park Avenue, facing the new Lever Building, and went to the very elite and public Bronx Science. I often wonder what became of her.) As I look back, going into The City (by subway) reminds me of the John Travolta character in “Saturday Night Fever,” when he visits his dancing partner, who has moved up in the world. She shames him into losing a brutish edge to his Bay Ridge behavior. But that, remember, was just a movie. We in Central Queens were pushed by post-war ideals and ambitions, many of our teachers setting examples of inclusivity. (By the way: New York City could not run Jamaica High in the 21st Century, so the city closed it down, history and potential be damned. See Jelani Cobb’s article: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-new-yorker-analyzes-the-end-of-jamaica-high) I tend to avoid all books about Trump. Just the journalism and the copious glimpses of Trump on the tube plus half a dozen meetings with Trump in less horrible times are quite enough for me. I love the reporting by Maggie Haberman, and the many insightful works of Joe Klein. But being caught up in a Trumpian caricature makes my Central-Queens skin crawl. A 300-pound man is gliding down the river in a canoe. His appearance, his shabby belongings stuffed into every corner, are straight from the last thousand homeless people you saw, under the bridge, on the subway bench. But Dick Conant did it differently. He had the intellect and knowledge of the med-school applicant he once had been. He could paint. He carried hard-covered books in his canoe, and some days he just lazed by the river and read. He also could read the river, could decipher the maps, could extract knowledge from other riverman (and more than a few riverwomen) he met on his missions along the Intracoastal. People on the banks, people seeing him lug his jumbled belongings through the streets, stopped to talk to him, were stunned by his intellect, by his knowledge, and also by his tales of a girlfriend named Tracy waiting for him back there somewhere. People never forgot him. America – free-falling into cruel anarchy these days – is built upon wanderers. It’s in our blood. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn and Jim. Daniel Boone and family making their way through the Cumberland Gap in 1769 as if it belonged to them instead of the natives. Lewis and Clark, ditto, toward the Northwest. John Ledyard’s canoe trip down the Connecticut River from New Hampshire – in 1773. The guy hitch-hiking on Route 66, singing to himself, a regular Chuck Berry. Dick Conant struck a chord. Sometimes the people on the riverbank, meeting this strange hulk, ingesting hot sauce the way other people suck on a Tic-Tac, grew quiet, as if confronting some inner wanderer. Hmmm, they thought. Hmmm. That’s what Ben McGrath, a writer for the New Yorker, thought a few yards from his home on the Hudson River, where the Dutch once encountered the Lenape. McGrath was fully nested, job, wife, growing family, but he was fascinated by this articulate and charismatic giant who secured his canoe near McGrath’s backyard. Hmmm. In the interests of journalistic/literary curiosity, McGrath chatted him up, and vice versa. And when the big man pushed off, McGrath went with him, in a way. Dick Conant was canoeing downriver for perhaps the last big jaunt of his wandering days, and McGrath tried to stay in touch. Then one day on a bad stretch of North Carolina river, the canoe turned up, but not the man. An authority found McGrath's name scribbled on a river map and called him, and McGrath wrote a haunting piece for the New Yorker. He was now into it, big-time, collecting every name and phone number and e-mail address Conant had scribbled somewhere. The only name and address missing was that of Tracy, the lost love Conant always said was waiting for him back in Montana, or somewhere. Now, McGrath has written a touching book entitled “Riverman: An American Odyssey,” recently published by Alfred A. Knopf, including photos of Conant, and photos of a few of his paintings. How did a college soccer player (Albany State) come to be most at home on rivers? McGrath writes about the large and complicated Conant family (he likes every Conant he meets) and all have their version of what happened to kid brother Dicky: too many drugs, too much booze, the late 60’s. (The book is worth it for the meeting at Woodstock between Dick Conant and Jimi Hendrix.) There is a one-sentence allusion to the young boy's quick exodus from a church summer camp: inexplicably, McGrath lets it sit there for many chapters before another quick allusion or two as to why Dicky left that camp, and never seemed the same. That human mystery aside, “Rivertown” is a touching ode to all river towns, most of them falling apart, a century past their prime, but inhabited by people still in touch with the water rushing past. I’ve known rivers (see below): Hannibal, Mo., two visits in the late ‘50s: Louisville, Ky., when my young family rode our bikes alongside the Ohio; as a news reporter, accompanying ecologists on a canoe glide on the Youghiogheny, a tributary of the Monongahela; Uncle Harold Grundy’s cottage in Bath, Maine, a few steps from the Kennebec he had dredged before WW II -- I never appreciated river towns as much as I do now, via the mobile Conant. McGrath solves no mysteries. He writes that Conant either sighted or imagined Tracy, a latter-day Dulcinea, an American Beatrice. Conant drank and danced gracefully in river-town bars, telling people how he was soon going soon to be with Tracy; women were charmed by his eloquent faithfulness; but he never got back. (Unless he’s there now.) ("Cathy, I'm lost, I said, though I knew she was sleeping ("I'm empty and aching and I don't know why." --- "America," Paul Simon.) McGrath writes the book half expecting Conant to ring him from some river town and fill him in on the empty canoe, about his recent adventures. The alternative is to slip onto the river in a suitable craft, just to see what’s out there. *** From the classic poem by Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," Gary Bartz has recorded his version: “I’ve Known Rivers.”  How strange, to be reading a book about the Holocaust while another slaughter takes place. For no good reason, I missed reading Art Spiegelman’s classic book, “Maus,” a graphic novel about his parents’ survival, of sorts, from Auschwitz. I always meant to read it since the first part was published in 1986, but just did not until now. However, when school boards and mayors and other American worthies began to ban this Pulitzer-Prize winning book as too controversial for young people, I realized I had to join the millions who had read it. I tried to take it out from the wonderful Nassau County library system only to discover I was 31st in the electronic waiting line – but fortunately there was a Spanish-language copy available from a few towns away. With my moderate Spanish and a handy dictionary – and the graphic panels displaying cruelty and hope – I read it. Meanwhile, a latter-day Hitler has decided to take over a neighboring people, even if he has to kill thousands, maybe millions, of them – “Man’s inhumanity to man,” to quote the Robert Burns poem, all over again, "a boot stamping on a human face – forever," in the words of George Orwell. Art Spiegelman was documenting it decades ago, as his aging father began to tell how the world fell apart in the late 30s in Poland, when the Nazis were flexing their muscles and most locals were none too hesitant to cooperate. Chapter by chapter, Spiegelman portrays himself, already an adult cartoonist with a political bent, getting his widower father to tell the story of his courtship and marriage and the inexorable plodding toward Auschwitz, followed by a reunion of the parents and the path to Rego Park, Queens, and the Catskills in the summer – heaven on earth, sort of, for people who have lived in Nazi hell. The artist portrays Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs, the British as fish, the French as frogs, and the Swedish as deer. What would the Russians be, if and when we get to a similar re-telling of this horror? Perhaps, lumbering, dim-witted bear cubs, with an old and rabid bear sending them off to mutual slaughter, up against a Ukrainian people with a (Jewish!) hero/president, trying to rally the world. As the father talks to his son, he tells how he and his wife went underground, surviving with the help of the occasional kindly Pole, and then how they survived in adjacent camps, he by being fluent in English and German as well as Polish – and learning skills that make him valuable to the warden, who feeds him, protects him. The father tells of death, step by step, of men around him. It’s a horror show, but also a testimony to the will to live – now being seen by Ukrainians who fight bravely for what is theirs, while many elderly and children are sent to relative safety. Spiegelman’s masterpiece is worth finding – buying -- and assimilating. In “Maus,” people are flawed, one way or the other, but the urge to survive against the wicked is strong. For the people of Ukraine, my heart goes out. Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize when she worked for The New York Times. Later, she wrote a best-selling book about the great northward migration of Black Americans. In the process, Wilkerson earned a ton of airline miles, allowing her to fly first class much of the time. In addition to the few extra inches of space, Wilkerson was able to do research for her new book -- on the caste system in the United States. Even when she presented her boarding pass for Seat 3A, she was still treated as a stranger, a lower caste, as a female and as an African-American. Confused flight attendants stared at her and suggested she just keep walking to the back of the bus. Wilkerson also had to endure jostling for overhead-rack space from white male passengers. Anybody who is Black, or has friends and relatives of color, knows the drill. A few days after the 2016 election, Wilkerson settled into her first-class seat and noticed “two middle-aged white men with receding hairlines and reading glasses” who quickly bonded, with one stranger telling the other: “Last eight years! Worst thing that ever happened! I’m so glad it’s over!” The two instant buddies then celebrated from Atlanta to Chicago, assuming that the new President would be "good for businss." I am 100 percent positive that Trump's appeal to money guys helped advance the racism loose in the country. . Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” came out in mid-2020, before the little lovefest of assorted cut-throats and sociopaths and bigots and other Trumpites at the Capitol. I just caught up with “Caste” and found it compelling, as Wilkerson compares America’s enduring racial prejudice with the age-old caste system in India as well as the caste system that killed at least 6 million Jews and others regarded as untermenschen in Nazi Germany. Wilkerson points out how Hitler studied how whites in America marginalized and terrorized Blacks long after the so-called Civil War. Wilkerson also points out that contemporary Germany does not display statues and markers of the Hitler days, whereas the U.S. is only now coming to grips with Black youngsters having to attend schools named after Robert E. Lee, that old secessionist-slavemaster. It never went away. Wilkerson also presents dozens of examples of lynching and mutilation of Blacks, under slavery and long into the 20th Century, and still going strong in spirit. Trying to understand the American system in terms of the Indian caste system, Wilkerson flew overnight from the U.S. to London to attend an academic conference on caste, attended mostly by people of Indian ancestry, whether English or Indian or other nationalities. She immediately realized that the elite castes – even among academics -- were identifiable by lighter (Aryan) skin as well as a deep aura of entitlement, whereas members of the Dalit (Untouchable) caste – even with doctorates and other professional titles - - were of darker skin and reserved demeanor. She became friendly with a highly educated Dalit at the conference who described how his sister had cried about her dark skin when it was time to seek a husband. From her new friend, Wilkerson learned about Bhimrao Ambedkar, who renounced his Hindu standing and became a leader of the Dalits in the time of Gandhi. Her education about India will surely be the reader's education. As I read Wilkerson’s book, I thought about the new demographics in the U.S., as it heads toward a “minority” majority in the next decade or two. The white terrorists who stormed the Capitol in January are quite likely feeling marginalized by the talented and poised people of color who have become more evident in recent years. Some kind of change was gonna come -- or so some of us thought. It's been in the public consciousness for decades -- with the great Sidney Poitier embodying a possible new era in the 1967 movie ”In the Heat of the Night." For other examples, Wilkerson mentions the intelligent and handsome and poised couple that lived in the White House from 2009 to 2017, plus examples of changing America all over public life. As the pandemic endures, I gain information on the evening news from professionals like Dr. Kavita Patel of Washington, D.C., Dr. Vin Gupta of Seattle, Dr. Lipi Roy of New York and Dr. Nahid Bhadalia, with their kind and patient faces, with their knowledge and passion. The international look of today’s medical experts reminds me of that very good movie, “Gran Torino,” when Clint Eastwood, an auto worker with dark secrets from his military service in Korea, meets his new physician. (I'll never forgive Eastwood for his ugly televised rejection of Barack Obama, but his movie shows the growth of an aging bigot in a changing Detroit.) Last week, on MSNBC, Lawrence O’Donnell presented the viral immunologist who helped develop the Moderna vaccine -- -- Kizzmekia Shanta Corbett, Ph. D., who turns 36 on Jan. 26. Dr. Corbett saw the code for this new virus as it popped in from China, early in 2020, and linked it, in her mind, with anti-virus codes available here -- “over a weekend,” apparently. The rapport was clear between Dr. Corbett and O’Donnell, who is proud of being of Irish descent in Boston, and is one of the most open champions of African-Americans in public life. However, at the same time, a huge swath of white Americans is acting out in public, scorning vaccinations and masks, storming the Capitol a year ago, yelling racial insults at police while trying to brain them with heavy weapons. Many white Americans grew up thinking they had an edge over anybody with darker skin. Isabel Wilkerson’s powerful book points out the growing strains on the old American caste system. * * * Dwight Garner, one of my favorite writers at the NYT, reviewed “Caste" in July of 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/31/books/review-caste-isabel-wilkerson-origins-of-our-discontents.html Lawrence O'Donnell's interview with Dr. Corbett -- real life, not a movie: One of my main regrets from my long association with the Commonwealth of Kentucky is that I have never met Wendell Berry. He was already a name in the papers – the poet who wrote with a pen or pencil, the agrarian who warned against forgetting the old ways of farming. He is still at it, age 87, somehow surviving without a computer or television, on his land in Port Royal, and still publishing whenever he feels like it. Finally, finally, with fires raging and tornados rampaging and strip-mine detritus floating past his farm on the Kentucky River, I picked up one of Berry’s most recent books, “The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry,” Selected and with an Introduction by Paul Kingsnorth, published by Counterpoint Press in 2017. Well, never too late – at least to read and honor Wendell Berry, if not to act on his warnings. Those issues were already out there from 1970-72, when my family moved to Kentucky for the Times, for me to cover Appalachia, and, as my wife puts it, “George lived in Harlan and I lived in Louisville.” Certainly, I covered what Wendell Berry preached – the damage from gouging coal from the fragile surface of the Cumberland Mountains; the need to farm intelligently and personally, not by corporation; the sellout by politicians who scorned the land for their own profit. (See: Manchin, Joe, a/k/a Blind Trust Joe, Commodore Manchin, and Worse.) But why didn’t I try to flash my NYT credentials and try to arrange an interview with Wendell Berry and his wife-partner-fellow-agrarian Tanya Berry? Goodness knows, I got around Kentucky. I met Harry Caudill, whose book “Night Comes to the Cumberland” made me want to go to Appalachia, to write about it. I got an epic private tour of Gethsemani Abbey outside Bardstown, and met the monk-colleagues of Thomas Merton, a few years after he died in 1968. I visited Pauline Tabor, the famed madam of Bowling Green, Ky., at her tasteful home with her majolica collection. I went campaigning with Happy Chandler on his nostalgia-trip final campaign. I got to know the McLain Family Band out of Berea. I also met Jean Ritchie, originally from Viper, Ky., the personification of Kentucky folk music, who also lived in our home town on Long Island. In Louisville, we lived next door to Rabbi Martin Perley, brave civil rights advocate, and his wife, Maie Perley, a writer. And I depended on the superb journalism of the weekly paper, The Mountain Eagle ("It Screams!") in Whitesburg, bravely issued by Tom and Pat Gish. And I interviewed Sen. John Sherman Cooper when he announced his retirement (in an era when Kentucky Republican senators were not necressarily vile.) Oh, yes, and I interviewed Loretta Webb Lynn of Butcher Holler, Ky., on the morning after she won country music’s Entertainer of the Year in 1971, and we stayed in touch. So you tell me: why didn’t I try to meet Wendell Berry?  His words and messages are very much out there. My Appalachian “correspondent,” Randolph Fiery, originally from West Virginia, often cites Berry as a spiritual and ecological inspiration, so I took out the book from the great Nassau County library system. Berry had me in the first pages of the first selection, “A Native Hill,” written in 1968 – in which he describes his odyssey in his 20s from academic and writer in the great cities to return to the land, owned by his family for six or seven generations. He follows the trickle of water toward the larger streams below: “As the hollow deepens into the hill, before it has yet entered the woods the grassy crease becomes a raw gully, and along the steepening slopes on either side. I can see the old scars of erosion, places where the earth is gone, clear to the rock. My people’s errors have become the features of my country.” Berry’s words touch off memories of the first house we bought, out east of Louisville, in an old place called Prospect. Builders had carved a freaking golf course into the plateau and our new house sat on the western edge, facing undulating plains – including a family cemetery. (The realtor promised us there would be no further development.) A trail led downhill, following the trickles, toward Harrod’s Creek. I loved walking alone in the woods – well, until a few months later a chunk of rock landed on our back lawn, nearly missing our youngest child -- from dynamite by a crew expanding the sub-division. Turned out the real-estate agent had lied, so we moved much closer to town, but my love of the woods remained. Now I recognize the very same flow of land in Berry’s descriptions of his family farm – from utilitarian Indian paths to dirt roads widened by soldiers and now, not far from his home, “its modern descendant known as I-71, and I have no wish to disturb the question of whether or not this road was needed.” I think of how many times I – or my family of five – barreled back and forth along I-71 toward home (New York) or the nearest city with baseball and other urban pleasures, that is, Cincinnati. Turns out, Wendell Berry’s farm – where he still farms and writes – is an hour to the East End of Louisville. But I never tried to interview Berry about ecology or strip mining or the diminution of family farms.  Berry’s beliefs resonate in his articles over the decade. In the chapter “Family Work,” Berry laments the long hours modern children spend cooped up in school: (“why should anyone be surprised if, under these circumstances, children should become ‘disruptive’ or even ‘ineducable’”) And in “Economy and Pleasure,” he describes the joy of taking his 5-year-old grand-daughter out to work the two-horse team in plowing some family land, and how she took to the reins. (I will not divulge her charming comment at the end of this utilitarian joy ride; she addresses her grandfather as “Wendell.” Cool.) For me, the last chapter was the best – “The Rise,” from 1969, as Berry describes a six-mile canoe sojourn down the Kentucky River – in mid-December – when the water was high, bringing him closer to modern life on the shores. The chapter reminds me of times I went out on Harrod’s Creek.with my friend, Dr. Sid Winchell. In "The Rise," Berry takes the reader to the time of the Shawnee and the arrival of Gen. George Rogers Clark to the still peaceful flow of the Kentucky River, even with all the debris floating alongside the canoe. Berry’s long life of farming and writing and loving the land awaken my sensibilities. I already mourn the new “settlers” in our wooded corner of the suburbs, who cannot wait to hack down trees, despite the first aid trees furnish a grievously wounded planet. Wendell Berry has been preaching to us for more than half a century. Long may he write. By pen or pencil, of course. *** (Mea culpa: written on a ThinkPad, using a Word program, issued by the Weebly site, via the Internet.) *** https://berrycenter.org/ Nice article by Silas House in 2020: https://gardenandgun.com/feature/wendell-berry-the-poet-of-place/ Maybe it’s the pandemic, but people seem to be forgetting the dangers of alcohol and gambling.

I base this on the recent approval of gambling outlets in New York State plus the avalanche of gambling advertisements on baseball broadcasts in the reign of Commissioner Rob Manfred. Um, does the name Pete Rose strike a familiar chord? Last I looked, that sick puppy is still banned for doing what the alluring TV ads urge people to do – bet the rent or the grocery budget on the wayward bounce of a baseball with Rob Manfred's signature on it., And the dangers of alcoholism seem to be minimized by a new movie directed (not produced, as I originally wrote) by, of all people, George Clooney, for whom I have high respect. Clooney has sent forward a movie, “The Tender Bar,” adapted from a fine book by J.R. Moehringer about his exposure to alcohol as a very young man, admiring his bartender uncle and missing his absentee father, leading to his eventual admission of powerlessness toward alcohol as an endangered adult. “The Tender Bar” movie is being hawked every couple of paragraphs on my incoming Web glut. I get the point. Little kid, hanging out in a pub, gets pulled into the life. I was tempted to push the button to watch the movie on my laptop, but then I read two rather different reviews of the movie in The New York Times. Critic A.O. Scott suggested the movie is lightweight, skipping from episode to episode: “Ít’s a generous pour and a mellow buzz.” But free-lance critic Chris Vognar takes a more critical look at the dangerous slide of a young man, made clear in the original book. Vognar writes: “…for a film with the word ‘bar’ in its title, it contains remarkably little insight about alcohol, where it’s consumed, and what it does.” The two critics talked me out of watching. Why, you ask, do I take gambling and drinking so seriously? I’ve seen gambling up close and have great respect for people who seek out Gamblers Anonymous and reinforce themselves, regularly. I have also seen alcoholism up close, having helped Bob Welch write his book, “Five O’Clock Comes Early,” about how he was having blackouts in his early 20s, jeopardizing his pitching career with the Los Angeles Dodgers, to say nothing of his life. By the time I signed on for his book, Bob was already sober from a hard month at a rehab center, and he was an advocate of daily reminders to stay sober. I later spent a family week at the center, and took a great deal from the process, from seeing endangered lives be turned around. Bob knew the dangers, and he verbalized them – part of the process. “I choose to be sober today.” As far as I know, he stayed sober for the rest of his life, which ended tragically young, 57, from an accident. Now I have a close friend who reminds himself daily how he, and Alcoholics Anonymous, saved his life. Why do these reviews of “The Tender Bar” strike close to home? As it happens, I live close to Moehringer’s home town, and have spent too many long minutes waiting for a red light to change, staring into the silhouettes in Moehringer’s pub. Plus, I have known several relatives of Moehringer, and have been apprised that he was not exaggerating his childhood. His book was great; I’ll skip the movie. Now, back to gambling. We all know how much money is gambled on sports, every day, everywhere. (The first college game I ever saw in the old Madison Square Garden was a dump, Kentucky stunningly losing to Loyola of Chicago.) I consider “Eight Men Out,” about the Chicago White Sox players who dumped the 1919 World Series, to be the best sports movie I know. Gambling did not go away when Pete Rose got busted for betting on baseball, including games in which he participated as manager (and, I am sure, as player.) I remember how the late baseball commissioner, Bart Giamatti, adamantly criticized all gambling --- including government-run lotteries. For Major League Baseball to permit gambling ads is dangerous; for New York State to permit gambling sites is also dangerous. (For that matter, I see that The New York Times, that great newspaper, is spending a ton of money to acquire a website, “The Athletic,” that is heavy into gambling odds. How does that impact the parent company when gamblers make or lose money via odds listed in that outlet?) We have a social brain fog that accepts drinking as a mellow haze that can be controlled, that encourages people to bet on capricious games. Then again, we see dopes like Novak Djokovic and Kyrie Irving and Aaron Rodgers misleading and blustering about vaccinations. Plus, an entire political party is going along with thugs invading the Capitol. Can we blame the pandemic for all this? I was trying to figure how to express thankfulness, and fortunately others have done it for me.

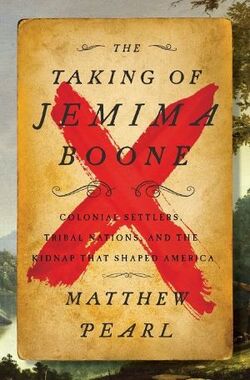

On Wednesday’s editorial page of the New York Times is a lovely essay by Tish Harrison Warren, an Anglican priest. (“This Year, Exercise Your Thankfulness Muscles”) Her fifth and last suggestion was “Take a gratitude walk,” about her young daughter who “invented something called the Beautiful Game,” finding sights that touch the heart. My responses to her essay: SIGHT 1: Fall Colors: I lifted my eyes off the printed page and saw the northern sky outside our home, with autumnal trees. Even though some people are figuring out that trees are vital in the struggle to save the planet, trees nevertheless are under attack in traditionally leafy suburbs like ours. The Town of North Hempstead, which pretty much allows leaf blowers and tree choppers to spew gas fumes and dust, making our suburb feel like an airport runway, is fretting over trees getting lopped off. These privacy-giving autumnal colors above are on our property, and we are grateful. SIGHT 2: A Young Nurse: The other day I had a common procedure as an outpatient at Glen Cove (Northwell) Hospital. The young nurse who prepped me was getting married – three days later. When they shooed me out a few hours later, I could still remember, over her mask, the glow of her eyes. I was thankful for skill, and youth, and hope. SIGHT 3: A Crowded Restaurant: The other evening, I took a walk around our town and slowed down outside Gino’s on Main Street. Since my wife sussed out the pandemic early in 2020, in our caution, we have not eaten out – not a terrible loss because she is such a good cook – but there are familiar places we miss in our town: Diwan on Shore Rd. and DiMaggio’s on Port Blvd. and Gino’s. I peeped in a side window at Gino’s and saw every table and every booth filled, the staff moving fast, and I hallucinated about a Gaby’s salad and a daily special and those hot chewy rolls and the cheesecake a la nonna for dessert. We’ll be back soon, I keep saying, but in the meantime I am thankful for the bustle at Gino’s. SIGHT 4: Books About Thanksgiving. I am currently reading “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer, about very different strains of English immigration in the New World. I never fully understood what it meant for settlers to call their new home New England – but as I watch a very divided country display major stress faults, I am more thankful than ever for the “New England” emphasis on education, producing a high level of literacy and study. May it prevail. As the U.S. Thanksgiving loomed, I took another book off our shelves, “Mayflower,” by Nathan Philbrick, who tries to re-create the fall of 1621: We do not know the exact date of the celebration we now call the First Thanksgiving, but it was probably in late September or early October, soon after their crop of corn, squash, beans, barley, and peas had been harvested. It was also a time during which Plymouth Harbor played host to a tremendous number of migrating birds, particularly ducks and geese, and Bradford ordered four men to go out “fowling.” It took only a few hours for Plymouth’s hunters to kill enough ducks and geese to feed the settlement for a week. Now that they had “gathered the fruit of our labors,” Bradford declared it time to “rejoice together…after a more special manner.” The term Thanksgiving, first applied in the nineteenth century, was not used by the Pilgrims themselves. For the Pilgrims a thanksgiving was a time of spiritual devotion. Since just about everything the Pilgrims did had religious overtones, there was certainly much about the gathering in the fall of 1621 that would have made it a proper Puritan thanksgiving. But as Winslow’s description makes clear, there was also much about the gathering that was similar to a traditional English harvest festival—a secular celebration that dated back to the Middle Ages in which villagers ate, drank, and played games. Countless Victorian-era engravings notwithstanding, the Pilgrims did not spend the day sitting around a long table draped with a white linen cloth, clasping each other’s hands in prayer as a few curious Indians looked on. Instead of an English affair, the First Thanksgiving soon became an overwhelmingly Native celebration when Massasoit and a hundred Pokanokets (more than twice the entire English population of Plymouth) arrived at the settlement and soon provided five freshly killed deer. Even if all the Pilgrims’ furniture was brought out into the sunshine, most of the celebrants stood, squatted, or sat on the ground as they clustered around outdoor fires, where the deer and birds turned on wooden spits and where pottages—stews into which varieties of meats and vegetables were thrown—simmered invitingly. In addition to ducks and deer, there was, according to Bradford, a “good store of wild turkeys” in the fall of 1621… The Pilgrims may have also added fish to their meal of birds and deer. In fall, striped bass, bluefish, and cod were abundant. Perhaps most important to the Pilgrims was that with a recently harvested barley crop, it was now possible to brew beer. Alas, the Pilgrims were without pumpkin pies or cranberry sauce. There were also no forks, which did not appear at Plymouth until the last decades of the seventeenth century. The Pilgrims ate with their fingers and their knives (117-118). * * * I am also thankful for readers of My Little Therapy Site, who contribute so much. Coming soon after Diwali, and with Chanukkah and its celebration of life following so closely, can you share any thoughts about thankfulness? * * * (With thanks to the website Reformation 21, Lancaster, Pa., for the excerpt from the Philbrick book: https://www.reformation21.org/about-reformation21 With thanks for the essay by Tish Harrison Warren: www.nytimes.com/2021/11/21/opinion/thanksgiving-gratitude.html?searchResultPosition=1ition=1  As soon as the final out settled in Freddie Freeman’s glove, I felt a surge – not quite the relief I felt when the Covid vaccine arrived in my arm but rather the excitement of a great swath of free time, suddenly arriving. Book time. I wasn’t reading hard-covered books during the warm months, but I kept taking notes about books I wanted to read. Now, no more long evenings obsessively watching the hapless Mets organization fall apart, in the person of Jacob deGrom’s pitching arm. Now, World Series over, free at last. The first book has been “The Taking of Jemima Boone,” by Matthew Pearl, about the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s most spirited child, on July 14, 1776. I was drawn to the subject because Daniel Boone was all over Kentucky when I lived in Louisville for two years, as the Appalachian news correspondent for the NYT, wandering the region. Boone's statue and name were all over the Commonwealth of Kentucky, as I drove on twisting roads that had been paths for him to explore, to hunt, to escape. But somehow I never wrote about him in all the time I roamed around Kentucky. Now Matthew Pearl, a novelist by trade, has written a taut drama, with a thick index in the back, assuring me that he was using source material and not only his novelist’s imagination. It’s a tricky time to be catching up on an American icon, most known for barging into Native American territory, often fighting for land, as well as for his life. The U.S. is re-evaluating its memorials to slave-owning Confederate generals, as well as explorers like Columbus. What to do about Daniel Boone? The reason Jemima Boone and two other girls in their early teens became prisoners is that Daniel Boone could not, would not, stay in coastal towns but pushed west through the Cumberland Gap and on, losing a son, driven by a tropism for space and land and “freedom.” This American icon was taking other people’s land -- at gunpoint – but his relationship to the people of the land was more complicated than that. He became part “Indian” in style and spirit. He was captured by a complex chief, Blackfish, who adopted Boone as a son, and recognized him as a kindred soul, with skills and courage. Boone, of course, was planning his escape. The actual “taking of Jemima Boone” occupies the taut first 75 pages of this book – how she tried to fight off the men who surrounded their canoe, how she left signals for the man she knew would come looking for her, and how she bonded, in a way, with the son of Blackfish, who treated her with respect, by all versions. Pearl, the novelist, resists going too far in suggesting a romance between captor and captive. In fact, one of the things I have learned from recent reading about New England settlement is that Indian males almost never raped, although some did “marry” their captives. It never came to that in this Kentucky encounter, but the details seem to have survived (with revisions, with exaggerations, surely) into the 19th Century, and then the 20th, and now the 21st. Matthew Pearl makes it real. Daniel Boone kept going, all the way to Missouri, where he and his wife Rebecca and Jemima Boone all died – of old age. He has two graves, one in Missouri, one in Frankfort, the Kentucky capitol. I recommend “The Taking of Jemima Boone” as a well-written and well-researched visit to a distant time, leaving complexities in a nation now re-examining (at long last) its myths and heroes.  I rarely read fiction these days; so much to learn from non-fiction. In spurts of reading, I have belatedly learned about Neanderthals and evolution and DNA, as well as the earliest “settlers” of New England. This has been spurred by my wife’s vast personal research in the genealogy of her family, from England and Scotland. Next in my reading list: “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer I was drawn to the book by a review by Joe Klein in The New York Times, with this overview: “Albion’s Seed” makes the brazen case that the tangled roots of America’s restless and contentious spirit can be found in the interplay of the distinctive societies and value systems brought by the British emigrations — the Puritans from East Anglia to New England; the Cavaliers (and their indentured servants) from Sussex and Wessex to Virginia; the Quakers from north-central England to the Delaware River valley; and the Scots-Irish from the borderlands to the Southern hill country. I consulted the index and found this one reference: “When backcountrymen moved west in search of that condition of natural freedom which Daniel Boone called ‘elbow room…’” Do these four separate waves of emigration explain why the United States, perhaps more than ever, seems to be several different countries, with rival impulses and outlooks? Does it explain Red and Blue states or regions? I look forward to learning what Fischer has to say.

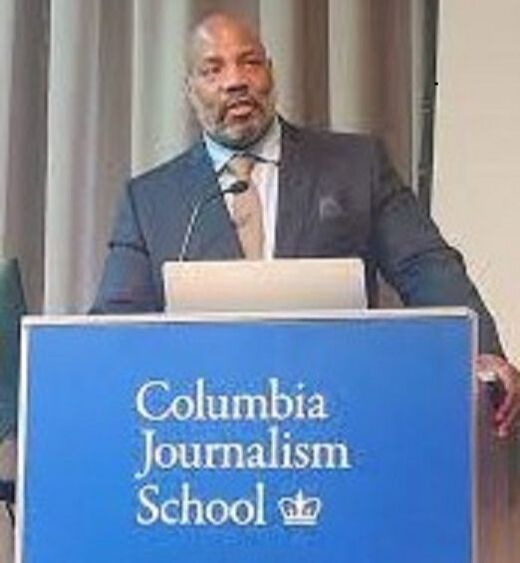

Clint Smith at Monticello Clint Smith at Monticello I just read a great new book: “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America,” by Clint Smith. Smith’s main point is that people, northerners and southerners, are now learning things about slavery they were not told in school -- the depths of depravity by which a female slave could be labelled a “good breeder” by her owners, and other aspects of good old-fashioned American enterprise. Many people in this country still see slavery through a sentimental haze: slaves were better off here than they would have been in Africa; they were handled benevolently at the plantations. You know, good people on all sides. Nowadays mayors and school boards and governors are trying to forbid controversial or academic critiques of America. (Some of these moronic governors are aiding Covid by not mandating vaccinations and masks at work and school.) Smith’s book about slavery lies is a companion to the so-called “Big Lie” about alleged election fraud and the merry tourists who flocked to the Capitol last Jan. 6. For all the chicanery and cowardice in high places, the worst parts of slavery are impossible to hide as Smith makes his rounds. As a one-time news reporter, I respect his shoe-leather approach -- visiting hot spots of the slave trade. A staff writer for the Atlantic – and a poet – Smith interviewed tour guides and museum directors as well as tourists, plus participants in Confederate commemorations. The new cadre of historians and guides make it clear that that people, white people, mostly male, not only performed violent deeds but also knew what was being done, mostly in rural and southern states. Smith begins where, in a sense, the country began – Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, where he "owned" slaves while preparing to write the Declaration of Independence. While he put pen to paper, his white staff put whips to the backs of Black slaves. Background music for Jefferson. At Monticello, Smith chats with two visitors -- white, Fox-watching, Republican-leaning women, who hear a guide talk about Jefferson’s long association with a female slave. Speaking to Smith, who is Black, the two women seem aghast. Smith quotes one of them: “’Here he uses all of these people and then he marries a lady and then they have children,’ she said, letting out a heavy sigh. (A reference to Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, who bore at least six of Jefferson’s children. The two were never married.) ‘Jefferson is not the man I thought he was.’” That is the theme of the book – many Americans in position of responsibility and knowledge deliberately deflected what was known about slavery. And not just in the South. I know somebody who did college research on commerce in New England, and never came across the mention of slaves in Yankee states. Then again, in a 2020 farewell to the great John Thompson, I praised a recent book about Frederick Douglass and noted that in all my school years in New York (with many history electives in college), I never heard the name "Frederick Douglass." (To be clear, I did know his name, just not from school. Our parents were part of a Black/white discussion group, and they extolled heroes like Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, and all of the children have learned from our parents.) Smith points out that the Dutch and English, who pushed out the Lenape natives, welcomed slaves on the oyster-laden shores of lower Manhattan, and used them for labor, and shipped thousands to farms and other towns. New York was the second largest entry port, distributing slaves culled from Africa. Those who died were tossed, unmarked, into a pit near Wall Street. One chapter in this book about slavery jarred me because I did not see it coming – a visit to the dreaded Angola Prison in Louisiana. Smith explains his visit to Angola by pointing out that Black prisoners worked for free or for pennies, at the penal equivalent of plantations. In fact, Angola had a big house, where the warden and his family were served by trusted Black prisoners. Prisons as plantations: As it happens, I have heard the metallic clank of the heavy door slammed behind me in three different prisons – and all three stories involved Black men. (See the links below.) Smith’s itinerary includes: Monticello Plantation, Va.; the Whitney Plantation, La.; Angola Prison, La.. Blandford Cemetery, Va., Galveston Island, Tex, where emancipation was belatedly revealed to Blacks, leading to the recent proclamation of a new national holiday -- Juneteenth; New York City; and Gorée Island, Senegal, the legendary focus for the African slave trade. In a moving Epilogue, Smith interviews his own elders for stories of prejudice, slavery and downright brutality they experienced or heard from their own elders. Clint Smith’s book makes it clear that white America knew more about slavery than it discussed -- just as many of our "public servants" like to talk about sight-seers who had a fun day in the Capitol last Jan. 6, brandishing flagpoles, gouging eyeballs and shouting racial epithets. It never went away. It’s who we are. * * * Two book reviews in the NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html Three of my stories from prisons, when I was a news reporter: https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/09/archives/frazier-sharp-in-tough-prison-talk-show-frazier-sharp-as-he.html https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/02/archives/new-jersey-pages-a-scholar-in-the-new-alcatraz-felon-finds-himself.html https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/12/archives/carter-reacts-stoically-to-denial-of-new-trial-i-hope-im-still.html * After writing this piece, and reading the thoughtful comments, I discovered a new book: “Land,” by Simon Winchester, a writer with great and varied interests. (We met in 1973 when he was posted to Washington by The Guardian.) Now living in the U.S., Winchester is writing about the creation and development of land.

An early paragraph about the original inhabitants of this continent fits right in with the tone of this discussion: (Page 17) “The serenity of the Mohicans suffered, terminally. The villagers first began to fall fatally ill – victims of smallpox, measles, influenza, all outsider-borne ailments to which they had no natural immunity. And those who survived began to be ordered to abandon their lands and their possessions, and leave. To leave countryside that they had occupied and farmed for thousands of years – and ordered to do so by white-skinned visitors who had no knowledge of the land and its needs, and who regarded it only for its potential for reward. The area was ideal for colonization, said the European arrivistes: the natives, now seen more as wildlife than as brothers, more kine than kin, could go elsewhere.” Winchester’s newest book then goes in many directions. I look forward to reading the rest.  Not too long ago, Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow were gracing the sports pages of The New York Times with their wise columns. Now they are both issuing books with their very personal views of the world. Harvey’s book is “Our Last Season: A Writer, a Fan, a Friendship,” about the bond between him and Michelle Musler, who for decades was a fixture in the stands just behind the Knicks bench in Madison Square Garden. Ira’s book is “How Life Imitates Sports: A Sportswriter Recounts, Relives and Reckons With 50 Years on the Sports Beat,” which just about tells it all. (In alphabetical order) Araton praises the wise businesswoman who was always there – for the Knicks and for him. He describes himself as the child of a project in Staten Island, who earns his entry into sports journalism while battling his own insecurities. As he works his way from the Staten Island Advance to the Post to the Daily News, his talent and earnestness impress not only editors and readers but also a fan literally looking over his shoulder in the Garden. Musler saw all – could read the body language, maybe even read lips, of the Knicks and the opponents and the refs. She had put her people skills to great advantage in the corporate world, undoubtedly by being wiser than the average (male) executive. The Knicks were her outlet, she freely told friends, her social life. Everybody knew her – the players, nearby fans, reporters, ushers, even the team PR man, who left a packet of media stats and releases for her before every game. How cool was that? Musler more or less adopted Harvey, counseled him, shaped him up, told him to aim big. She became friendly with Harvey’s wife, Beth Albert, and sometimes met Harvey after a game to debrief him on what she had seen from her perch. When he fretted whether he was worthy of the Times job being offered, she figuratively slammed him up against a steel locker and gave him what a high-school coach I knew called “a posture exercise.” And when his career took a sour detour, she shaped him up, to the point that in retirement he remains an extremely valuable contributor to the Times sports section. Harvey is still what somebody once called him: “The Rebbe of Roundball.” In return, Harvey came to know Michelle Musler – her strange childhood, her husband leaving her with five children, her career, her need to make money, her love of the Knicks. Her decades of working with male executives prepared her for a searing analysis of James Dolan, the miserable owner of the Knicks. As Michelle’s health deteriorated, Harvey would sometimes drive from New Jersey to Connecticut to the Garden to get her to a game. And when Michelle Musler passed in 2018, Harvey wrote a beautiful obit for the Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/obituaries/michelle-musler-courtside-perennial-in-the-garden-dies-at-81.html  Ira Berkow’s book is also personal – about a talented, ambitious kid from Chicago who made his way to New York and became a fixture in the Times and also in books, not all about sports. Ira has touched on most stars of the past half century – Muhammad Ali! Michael Jordan! He sized up O.J. Simpson, before and after! He had lunch with Katarina Witt! He shot baskets with Martina Navratilova! He also shot baskets with a retired Oscar Robertson! He schmoozed with Abel Kiviat, then America’s oldest living medalist! And he scrutinized a brash real-estate hustler named Donald Trump! One of my favorite segments is about Jackie Robinson – who broke baseball’s disgraceful color barrier in 1947. Ira recalls being 15, a high-school athlete himself, watching the Dodgers take on the Yankees in the 1955 World Series. In 2018, with JR42 long gone, Ira was being interviewed on TV about Robinson and came up with a description of how Jackie Robinson had faked the Yankees’ Elston Howard -- a catcher playing left field -- into throwing the ball to second base while Robinson steamed into third. Later, he remembered interviewing Robinson in 1968 about his thought processes in testing Howard, who was out of position because Yogi Berra was the catcher. Robinson seemed to deflect Ira’s analysis, but the audacious move remained in Ira’s fertile brain. A few years ago, Ira looked it up in the official play-by-play for the 1955 Series: it confirmed that Robinson, by whatever logic, had victimized Howard into throwing behind Robinson. This section confirms the instinctive genius of Jackie Robinson and also the enlightened journalistic observation powers of Ira Berkow. * * * Most of sports have been thrown off balance by the pandemic, but these very different books by Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow remind us how great sportswriters have enriched us by writing about the world, on and off the court. One of my favorite e-mail correspondents is Bill Lucey, a journalist and baseball fanatic in Cleveland. (We have never met.) Occasionally, Lucey writes a blog, but he goes beyond the stereotype of the guy-in-underwear-slapping-together-a-pronunciamento. He actually contacts experts for their opinions. The gall of him, working at his blog. His latest is a very well-written look at the acceptance of the word "irregardless" by an alleged authority in grammar. He writes about other innovations, including one taking place in Major League Baseball is this very shaky season. Ladies and gentlemen, readers of all ages, please open the following link and read Bill Lucey's erudite essay on the dumbing down of grammar: https://www.dailynewsgems.com/2020/08/due-to-popular-use-irregardless-now-a-word.html?fbclid=IwAR3KVy2cU0t54EnHZ1QlNKmzxe18NmFLXNpRytg6-2FnSrmFtEFqoGPLC90 * * * *- My little joke. One of my pet peeves is the misuse of the word "hopefully," particularly by sports broadcasters, but also by many people who speak in public. * * * And while you're at it, check out this site for very short plays. This one is by my friend Altenir Silva, from Rio and Lisbon, Yankee fan, writer in English, frequent presence on this site. He has written a shortie about Godot, as performed by Abbot and Costello. Honest. Of course, it has allusions to baseball. I told you, he's a Yankee fan. The link: https://www.scene4.com/0820/altenirsilva0820.html The first of December was covered with snow So was the turnpike from Stockbridge to Boston The Berkshires seemed dream-like on account of that frosting With ten miles behind me and ten thousand more to go ---James Taylor, “Sweet Baby James” Snowing again, this first of December. This typist has little to say on this left-over Sunday. Over the holiday, I’ve been reading “Poems of New York,” selected by Elizabeth Schmidt, while my wife is reading “Underland,” by a philosopher-explorer, Robert MacFarland. Thank goodness for writers. Pete Hamill is writing a book from his home borough of Brooklyn. Pete is among the three great print troubadours of my home town – along with Murray Kempton and Jimmy Breslin. (Dan Barry would make a quartet, when he is in print.) Hamill is not well, as documented by Alex Williams in the Sunday Times, but he is going to get his Brooklyn book done, he says. Also gutting it out is the great film director, Michael Apted, who has just issued his latest documentary – and, he says, his last – in the seven-year cycle about English youths who grew older, the ones who were lucky. I have a great debt to Michael Apted for putting Loretta Lynn’s story on the screen, after I helped her write her book, and Tom Rickman wrote a magnificent film script. I was afraid Hollywood would turn Loretta’s world into a segment of “Beverly Hillbillies,” but as Rickman told me about Hollywood: “Sometimes the good guys win.” I got to thank Apted when the movie had its premiere in Nashville and then in Louisville. Invited along for the chartered bus ride up I-65, I asked Apted how he got the feel for Eastern Kentucky and he talked about his roots in England – not just London – and he said, “I am no stranger to the coal mines.” Good luck with your new movie, sir. Today belongs to talented people like James Taylor and Pete Hamill and Michael Apted. A friend recently gave me a couple of poetry books, one by Seamus Heaney, the other a collection about my home town. I include a segment from Nikki Giovanni, about the sudden flashes of humanity you encounter just about anywhere in the city. This is about a blind woman, uptown. You that Eyetalian poet ain’t you? I know yo voice. I seen you on television I peered closely into her eyes You didn’t see me or you’d know I’m black. Let me feel yo hair if you Black Hold down yo head I did and she did Got something for me, she laughed You felt my hair that’s good luck Good luck is money chile she said Good luck is money. -- From “The New Yorkers” I’ll leave it there. Keep writing, Pete Hamill. I’m waiting on your Brooklyn book.  In this ugly time, I tear up when reminded of the knowledge, the eloquence, the idealism of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama. Sometimes, I entertain the fantasy that Mrs. Obama will offer herself as a candidate for President – not that I would subject her, or her family, to the viciousness of another campaign, another presidency. Besides, any ephemeral hopes have been dashed by reading Mrs. Obama’s stimulating book, “Becoming,” which confirms what has seemed apparent: since she was young, Mrs. Obama has felt a visceral distaste for politics. In her book, she recalls qualifying for the elite Whitney M. Young Magnet High School, which entails a long two-bus commute, but also introduces her to new friends like Santita Jackson. Sometimes, after school, she is invited to the Jackson home, which takes on a frenzy when the man of the house, Jesse Jackson, is in town, making plans for one campaign or another. One day Michelle and Santita find themselves “conscripted” into marching in the annual Bud Billiken Day Parade on the South Side. “The fanfare was fun and even intoxicating, but there was something about it, and about politics in general, that made me queasy,” she writes. When she comes home that afternoon, her mother, the stalwart Marian Shields Robinson, is laughing, saying: “I just saw you on TV."  Michelle Robinson Obama has always known her own mind. She was enough of a realist to admit that she had fallen for a charismatic summer intern at the law firm she had worked so hard to join. Barack Obama had many plans and dreams, and in her telling, she had enough faith in him that she would change her own life around. That is the first half of the book – how Michelle was raised by Fraser and Marian Robinson, and her older brother, Craig, a basketball star at Princeton, and strong-willed, talented relatives. The richness of her family life – the wisdom of her parents – challenges any stereotypes of African-American life that might get thrown back at the Obamas, to this day. The second part of the book is about Michelle Obama’s reactions to her husband’s abrupt rise to presidential candidate. Mrs. Obama describes how campaign aides failed to prep her for public appearances, leaving her to improvise. She realized she was no longer primarily a lawyer or community organizer but a political spouse who can jangle a campaign with one impromptu phrase. A born organizer, she seems to have impressed upon the handlers: That won’t happen again. She describes election night in 2008, when her husband, seemingly so confident, watched on television, and how her mother reached out and patted his shoulder. Mrs. Obama describes how much she already admired Laura Bush from afar, for her poise and advocacy of books. During the transition, she quickly came to like Mrs. Bush’s husband, and has often been photographed hugging and laughing with him.

She describes life in the White House, how close the family – including her mom -- felt to the mostly-black staff, and how much she relied on advisors to help with her interest in nutrition and gardening and with her wardrobe. She praises the President as a loyal husband and father. I know this is true because a journalist friend of mine, who often traveled on the Presidential plane, told me how day trips were planned to get the entourage back to Washington in time for the Obamas’ 6 PM supper in the White House. How Michelle Obama really felt about being a White House wife comes out in one of the most charming anecdotes in the book: On the evening of the Supreme Court ruling in favor of gay marriage, large crowds celebrated in front of the White House. Michelle and her older daughter, Malia, made a break for it, rushing past their guardians, finding an exit to a quiet corner of the garden, just to feel and hear the jubilant crowd. For a few minutes, they beat the system. There are many sweet memories in this book (written with the help of a talented journalist, Sara Corbett): the entire family meeting an elderly Nelson Mandela in his home, and feeling so comfortable with Queen Elizabeth, who motions for Michelle to sit next to her, referring to palace protocol as “rubbish.” The book includes gracious mentions of all the people who helped her, and minimal references to the candidate who tried to portray her husband as an illegal alien. I would have liked to hear what Michelle Obama really thinks of that man, but the Obamas live by smart lawyerly aphorisms: “Don’t do stupid stuff.” And “When they go low, we go high.” In its high-minded way, Michelle Obama’s book reminds me that this family has earned its independence, mostly out of the spotlight. We were lucky to have them. Things are in the saddle/ And ride mankind. – Ralph Waldo Emerson

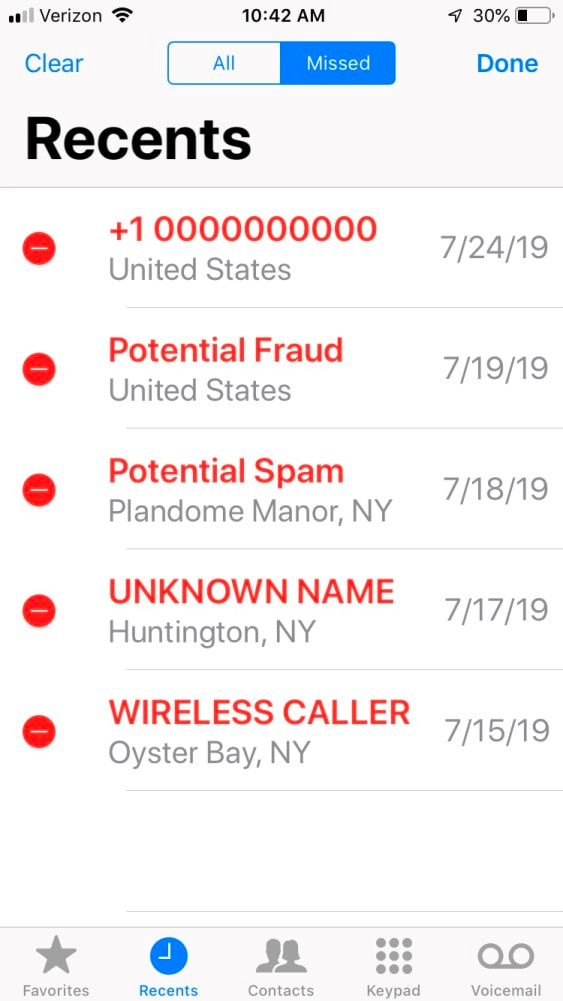

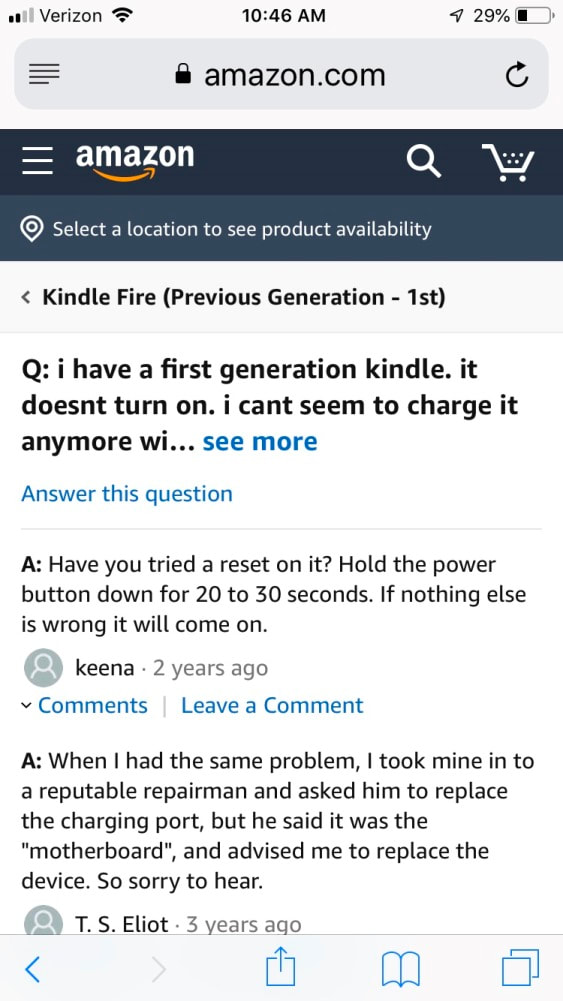

Salinger is going digital. I read it in the Times. This makes it possible to read the late and reclusive author on your device of choice, flicking words and sentences and paragraphs that the master put down on paper. Perhaps this is progress, or perhaps not, depending on the reliability (the planned obsolescence, the health of the battery) of your particular device. I say this with the cynicism of somebody who manages smartphones and laptops and TV remotes with perhaps better-than-average skill for somebody in my age group (that is to say, old.) I mean, I assemble this little therapy website. Lately I have spent far more time than I ever could have imagined in the clean, well-lighted Apple place where they administer what I have come to consider electronic methadone. There’s always something. As Salinger goes digital, here are two of my most recent adventures with gadgets: 1. I recently bought an iPhone 8 when my 6-Plus reached obsolescence, just as, I am sure, Apple intended. (It’s not the instruments, they tell you with a straight face, it’s the upgraded programs.) The adjustment has been easier than I expected, and there is one fascinating new feature involving robocalls, the price we pay for having a smartphone. I’ve learned not to answer when I see numbers not already linked in my Contacts. This way I avoid conversations with “Billy” or “Betty” in some call center in India. To my fascination, the new iPhone 8 categorizes unknown callers. Potential Fraud. (Casey Stengel called some of his early Mets “frauds.” Nothing personal. They just couldn’t play.) Potential Spam. (What a wonderful term – reminds an oldster of the vaguely meat product we ate during World War Two.) Unknown Name (Thanks for the warning.) Wireless Caller: (Could be just about anybody.) They all get banished to incoming Limbo. 2. The down side of technology is, of course, that stuff doesn’t work. Back in the dark ages, that is to say, 2012, my wife obtained a Kindle device for storing books. A family member gave her a few books about Turkey for our upcoming trip (that turned out to be epic.) But then we didn’t use the Kindle for years. The other day we found it on a shelf, and opened it, and I read the first few chapters of “Istanbul: Memories and the City,” by Orhan Pamuk, who has become one of my favorite (contemporary) writers. Then I got the bright idea of recharging the device. I used the proper plug but it all went dead. I had no booklet of instructions so I went on line and read about the sudden mortalities of Kindles, how they just stop working. From reading the wisdom of consumer-survivors, I determined that you first try re-booting it, and then give it a sharp smack with your hand, If that low-tech stuff doesn't work, and you possess the skills of a cat burglar, then you buy a little kit, pry the case apart, make your own repairs and replace the battery. Or, you “find someone” who repairs Kindles. Unless, of course, the “motherboard” (whatever that is) goes. Then it’s over. Go buy a new one, sucker. The great maw of Kindles has swallowed our few Turkey books, but my wife came up with a great solution – books, with pages and covers. Our house is full of books, plus, they just may be making a comeback against the novelty of gadgets that depend on batteries and kits and motherboards. Plus, in my town of Port Washington, L.I., we have have the Dolphin Bookshop, right near Manhasset Bay, and a few blocks up the hill we have the Port Washington Public Library (with a reading room overlooking the aforementioned bay.) The library is connected to a consortium that delivers books from libraries all over Long Island. The defunct Kindle? One more gadget to toss at the next electronic cleanup at the town dump. Holden Caulfield would not be surprised. All championships are miracles, somewhere, if you think about it.