|

I’m finishing up a four-day sabbatical from watching baseball – although not necessary from thinking about baseball, talking about baseball, writing about baseball. Fact is, two friends – former ball players, now faithful e-mail correspondents, have added to this missive – and a few family Mets fans pulled me back into the game when I was supposed to be resting my brain. I had made a conscious decision to avoid the All-Star Game on Tuesday, plus that gimmick called the Home Run Derby on Monday. Like many Mets fans, I had my fill of mood swings in the first half of the season – the Mets stunk, too many pitchers I never heard of, too many rumors that Pete Alonso would be scuttled. But then the Mets made a gallant run in the month or so before the All-Star Game, rushing into third place. I watched so much that I could justify ducking the all-star events. Plus, I cannot stand network baseball -- too much witless testosterone from old stars, too much born-yesterday overkill from the network booth. I wanted the terrific Mets commentators – Cohen, Darling, Hernandez, plus Good Old Howie Rose on the radio -- to rest their lungs, their eyes, their wits. And I would do the same. However, on Tuesday evening, I was listening to the dulcet tones and expertise of Terrance McKnight on WQXR-FM, when I heard my cellphone popping. It was a family member griping about the garish uniforms on the all-stars, a comment backed up by two family Mets fans upstate. I flicked on the tv, saw the ridiculous gear --convinced all over again that Commissioner Rob Manfred has no feel for the sport. Bad enough baseball is now in bed with gambling dens. Now it is hustling overkill uniforms. Back to classical music. However, two friends were still buzzing about the all-star uniforms. I heard from Bill Wakefield, who pitched for the Mets in 1964 and has saved up a lifetime of memories. (Pitching to Willie Mays! Running around New York with Hot Rod Kanehl! Studying Casey Stengel up close!) Now a retired businessman in the Bay Area, Wakefield proposed baseball switch to uniforms sported by barnstorming teams with Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Good idea. Wakefield wrote about the first all-star game he remembered from his youth in Kansas City – a rain-shortened game in Philadelphia in 1952, won by diminutive lefty Bobby Shantz. Yes! I also heard it on the radio. Wakefield’s reverie triggered my memory of the first All-Star Game I attended – 1949, my father took me to Ebbets Field, great seats behind home plate. For whatever reason, one of my strongest memories is Andy Pafko of the Chicago Cubs, getting a hit, running the bases in the the Cubs’ traditional home uniform, with red logo. What a concept! I sent my Pafko memories to Wakefield, and also to my friend, Jerry Rosenthal, all-conference shortstop at Hofstra College in 1960, then two years as an infielder in the Milwaukee Braves farm system. Jerry – from Madison High in Brooklyn! – had the immense good fortune to study under farm-system coaches Andy Pafko (who had been traded to Brooklyn in 1951) and Dixie Walker (the Peepul’s Cherce in the mid 1940s.) Jerry, later a schoolteacher in Brooklyn, came through, as I knew he would, with his memories of Pafko and Walker. From Jerry Rosenthal:  I was thrilled by seeing that Andy Pafko baseball card! I will never forget Andy ; one of the finest men I ever met! During the Braves' minor-league spring training camp of 1962, in Waycross, Ga., I got up the courage to asked Andy about "the shot heard round the world"! It was in the "rec" room, after one of our afternoon games. Somehow, I was one of Andy's favorites. That was partly because I was from Brooklyn and we could talk knowledgeably about the old Dodgers and the wonderful Brooklyn culture of the early 1950's! By the way, Dodger fans loved Pafko! Andy told me that he actually cried when when the Dodgers traded him to the Braves! He also said that his time in Brooklyn were his happiest years in baseball!” (Jerry recalled how he asked about Pafko’s moment in 1951, watching Bobby Thomson’s home run sail over his head into the lower deck at the Polo Grounds.)

Jerry wrote: "I finally asked him about Bobby's historic "shot." "I distinctly remember Andy saying: "I played many years with the Cubs, so I knew that that any hard-hit ball in the air that was pulled by a right handed hitter was going out! He added that "he could, at times, tell by "the crack of the bat" when the ball was gone"! He said he “heard it clearly." "Maybe that was because of the sparse crowd at the PG on that momentous day! "That iconic picture of Pafko looking up at the lower- left field deck is branded in the collective memory bank of even the casual baseball fan! "Most fans still think Bobby's homer was hit into the upper deck, maybe that was because it looked like Andy was looking high up! Andy told me that he always got this question: "Did you think you had a chance to catch the ball?" It was impossible to jump anywhere near a wall that was fifteen feet high! "Durocher actually commented on the rarity of homers being hit into the lower left field deck; most homers were hit into the overhang of the upper deck! Bobby hit a sinking line drive off a fastball! it quickly disappeared into the lower deck! "As fate would have it, Bobby Thomson was traded to the Milwaukee Braves and roomed with Pafko for a few years! They became close friends. At first, Bobby wore his number 23, the same number as when he was with the Giants, until he switched to 25 the next year. "I wore that hand-me-down number 25 jersey at Eau Claire. Wish I had that jersey today with "Thomson" embroidered in red thread on the inside. By the way, picture available.) "Here's a fact that most baseball fans never mention: Andy Pafko took over the third base position from Stan Hack in 1945 and played third base in the Cubs - Tigers World Series. "The Associated Press named Pafko to the All Star game as the starting third baseman, even though the game was not played in 45' because of the War. "So Andy was one of the rare major leaguers who made the All Star team playing two positions ( all told- Pafko played in five All Star games - one at third base and four as an outfielder ). "Pafko ended his wonderful ML career by being replaced in right field by Hank Aaron! Not a bad way to go out!" *** (Jerry, who was in several English classes with me at Hofstra, finished with a flourish:) "George, couldn't agree more about those beer-league uniforms worn by All Star players! It irritated me so much I watched part of the Republican Convention! "I took an antacid tablet and went to bed! " *** GV: I have the feeling baseball is going to come in handy in the months to come.

16 Comments

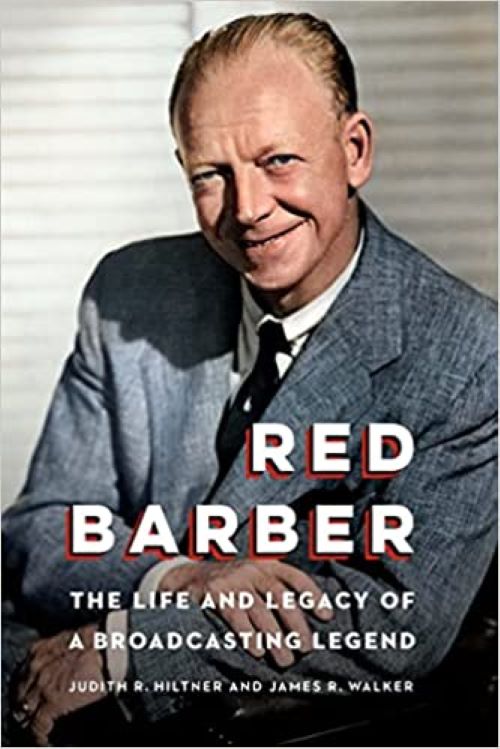

I worked myself into a tantrum last Friday when Max Scherzer was making his first start for the Mets. I wanted to see the game, plus hear what the Mets’ knowledgeable TV triumvirate of Cohen-Hernandez-Darling had to say about it. Then I found out that Major League Baseball had farmed out this game to some Apple outlet, with unfamiliar broadcasters. Yes, the very same Rob Manfred operation that now welcomes gambling commercials. (Coming next year: commercial patches on uniforms. Baseball goes Nascar.) I knew enough to instantly switch to Good Old Howie Rose, of course – baseball is a great sport for radio, with lifers like Rose -- but people who could not access WCBS-AM radio (upstate New York, for example) were stuck with the gimmick -- noisy strangers hawking silly “probability” statistics but clueless about the daily workings of the Mets. Baseball clearly has no shame. * * * Totally by coincidence, I have been reading a biography of one of the great baseball broadcasters of all time, Red Barber, who introduced my brain, my heart, my ears, to the Brooklyn Dodgers, starting in 1946. My earliest baseball memories are riding around Queens with my father, with Red Barber on the car radio, and listening to night games in our back yard, via a radio that occasionally emitted shocks from a faulty connection in the garage. Red Barber’s melodic southern accent calling a Jackie Robinson foray on the third-base line, on a warm summer night, outdoors? The best. Later I got to know Red in the Yankee Stadium press room, in the 60’s, after he had switched over to the “big ball park in the Bronx” – his alliteration, not Mel Allen’s. Walter Lanier Barber had respect for the game itself, and for the intelligence of the listener, and for the rules and codes of life. I did not know, back then, that Barber was also a lay preacher, but what I did know was that he stood up for the right thing, by his standards, and he offered a measured response when things did not go the Dodgers’ way. He was not an overt rooter, did not refer to ”we,” did not make excuses for Dodgers. On the final day of the 1950, the Dodgers had Cal Abrams thrown out at home, and then lost the pennant on a home run by Dick Sisler. I can remember listening in my family house, as Barber delivered what I took as a sermon of sorts, that life would go on, there would be another season. It helped me get through another Yankee World Series – a piddling issue, to be sure, but he gave hope; there were more important things in life. Now I know Red Barber better, through a valuable new book, “Red Barber: The Life and Legacy of a Broadcasting Legend,” by Judith R. Hiltner and James R., Walker, published by the University of Nebraska Press, which often issues serious sports biographies and histories. Red Barber deserves this adult biography. The book takes me to Barber’s southern childhood, his hard-working father and idealistic mother, a very segregated world, and even Barber’s youth as an entertainer doing – gasp – minstrel music, mimicking stereotypes of Black music. As the young and very ambitious man, morphed into a broadcaster, he was lucky to be instantly taken with a young nurse named Lylah Scarborough, also very southern, but with a difference: she had played with Black children, and had treated Blacks in her profession. The book shows how Miss Lylah prepared Barber to adjust to the advent of Jackie Robinson in 1947, and also to enjoy the culture of the city. He never denied it: he was a work in progress, with help from his mother and his wife. Barber broadcast many sports, eventually on national networks, but his specialty was baseball, first in Cincinnati, then in Brooklyn. He had a code: he could drop folksy sayings (“rhubarb,” “catbird seat”) in his southern cadence, but he had to remain an adult on and off the air. He took his cue from his father, fighting for better contracts; he also learned from Branch Rickey, the innovative, educated and religious boss of the Dodgers. Barber knew he was speaking to Dodgers’ fans but he did not root – was not a “homer,” in the press-box slight. He also did not go along with certain broadcasting ways: calling the 1947 World Series, he told the national audience that Bill Bevens of the Yankees had not given up a hit with two outs in the ninth. The superstitious blamed Barber after Cookie Lavagetto broke up the no-hitter but Bevens assured Barber, heck, it was Bevens’ own fault for walking so many hitters. When a new owner named Walter O’Malley took over the Dodgers, Barber continued to tell the truth. Once he informed the radio audience that the opposing infield was playing deep for a double play because Carl Furillo, the Dodgers’ stalwart right fielder, was notoriously slow. Any true fan knew that already – the great Dick Young had labelled Furillo “Skoonj,” a slang Italian reference to snail -- but O’Malley dropped a snide remark on Barber the next day. Not long afterward, Barber was calling Yankee games, remaining his own man, once noting the sparse crowd (413 paid) for a late-season Yankee game. More broadly, as the book emphasizes, Barber’s austere presence became out of style. Time to move on. Barber spent his final decades back in Florida, still a national figure, from his Friday morning NPR “Morning Edition” conversations with Bob Edwards, plus writing and speaking and eventually caring for Miss Lylah when she developed Alzheimer’s. He died in 1992 and she in 1997. Sports broadcasting has continued to evolve. I would submit that the booth of Cohen-Hernandez-Darling bristles from the individual gifts of all three, starting with honest calls from Cohen and his enlightened questioning of his booth mates -- former ballplayers, a genre that Barber disdained. Hernandez offers the perspective of a fiery on-field leader and Darling offers the perspective of a Yale star who does his homework. My guess is that Red Barber – who was always looking for another protégé like Vin Scully -- could have worked with all three of them. Baseball fans will enjoy this serious biography of an evolving adult who set a high standard for broadcasters, players and fans. Red Barber could get excited. Here is his classic call of the game-saving catch by Al Gionfriddo in the 1947 World Series -- watch Joe DiMaggio make a rare show of frustration. Barber's exclamation of "oh....doctor!" was not a stock phrase of his. He just blurted it.

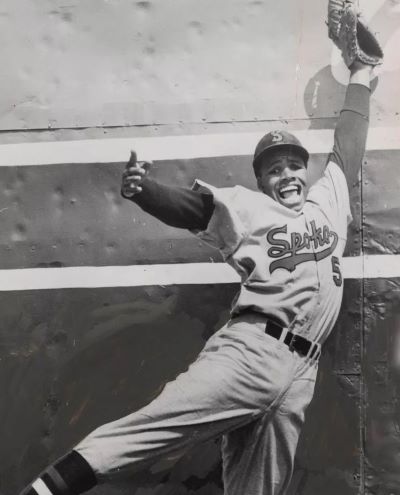

Tommy Davis in his short stint in minors at Spokane. Tommy Davis in his short stint in minors at Spokane. Tommy Davis always remembered where he was from. Whenever the Mets would play in Los Angeles, the assorted chipmunks and walruses of the large NYNY media corps would tromp over to the Dodger clubhouse to schmooze with the team that used to play in Brooklyn. As soon as he sighted familiar faces – or heard familiar Noo Yawk accents – Tommy would turn to his teammates and announce: “Hey, these guys are from my hometown.” And he would chat with reporters about one thing or another. Tommy Davis was always a New Yorker at heart This comes across in the lovely obit in the Times, by Glenn Rifkin, that describes Tommy and Sandy Koufax celebrating with a made-in-Brooklyn victory dance in the clubhouse after a 1-0 victory. One thing that would always come up – that is, I would bring it up – was the damage Tommy did to one of my best friends from school. It went back to March of 1956, in the PSAL basketball playoffs, then held in the old Garden between 49th and 50th streets. Tommy was one of the mainstays of the Boys High team (now Boys and Girls High) and he showed an eye fore talent by cajoling his pal Lenny Wilkens, a feathery guard, into playing one semester for Boys, but Wilkens --now a Hall of Fame pro player and coach-- was out of eligiblity by the playoffs. In a second-round game, Boys was playing Jamaica High, the defending city champion from 1955. One of the Jamaica regulars was my pal since the seventh grade, Stanley Einbender, a very solid forward. Stanley was waiting for a rebound when, from the upper stratosphere of the Garden, came Herman T. Davis, Jr., of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Davises. On his way downward Tommy happened to clip Stanley on the forehead, producing blood, and requiring Stanley to leave the game for medical attention. Boys won -- it would have won anyway -- and Stanley became the rock of a great Hofstra team from 1957-60, with a not very noticeable scar on his forehead. Later he became an endodontist and we are friends to this day. In our 20s, whenever I ran into Tommy – particularly in the Dodger clubhouse, with other Dodgers listening – I would tell the tale about how he clobbered my pal in Madison Square Garden, and that my friend was now a dentist looking for revenge. Tommy loved that story. Tommy Davis showed great perseverance in playing on, after a gruesome broken ankle while sliding when he was a young star. His gait was affected, but as the obit notes, the designated hitter rule, that began in 1973, kept him in business. Whenever I got too snooty about the DH being a “gimmick,” I thought of Tommy Davis struggling to run the bases, and I toned it down a notch or two. They never met, but one wintry Sunday a decade ago, Tommy was in Queens, at a memorabilia show, signing his autograph. I greeted him, and ostentatiously took out my cellphone and called Stanley, an hour east on the Long Island Expressway and said, “Here’s your chance.” But Stanley couldn’t make it, for one reason or another. I would have loved to be there for a second meeting of these two brothers of the backboard. * * *

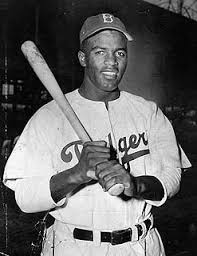

AN APPRECIATION OF TOMMY DAVIS (AND BROOKLYN) FROM MY FRIEND JERRY ROSENTHAL (great shortstop at Hofstra, Madison High and Milwaukee Brave farm system): George, thanks for remembering Tommy Davis, one of Brooklyn’s greatest athletes! I played against Tommy in the Parade Grounds League back in the mid-50’s. Tommy played center field on the Brooklyn Bisons, alongside Lenny Wilkins. I played third base on the Brooklyn Avons. My James Madison High School teammate, Teddy Schreiber played shortstop on the Avons. Those were the halcyon days of amateur baseball in Brooklyn. The Dodgers were going strong and baseball was the only game in town! Life was good! The Parade Grounds is located adjacent to Prospect Park. In those days, it was made up of of 13 diamonds which were fully occupied on weekends - from 8 AM to 6PM. Diamonds 1 & 13 were the showcase fields usually featuring the best senior division teams ( ages 16-18 ). Sometimes a playoff game would draw up to two thousand fans along with a dozen scouts. The Bisons were a long established Black team in the Parade Grounds. Make no mistake about it, there were no integrated teams back in the 50’s! However, the Bisons did have a few white ballplayers on their club. How ironic! After my final high school season in 1956 , I was invited to Ebbets Field to try out for the “Brooklyn Rookies,” a promotional team that traveled around the Metro area playing highly rated amateur teams. Davis had already signed and was playing at Hornell , N.Y. in the New York Penn League. I didn’t make the Dodger Rookies team which was a major disappointment! However, two weeks later I was invited to attend a tryout at the Polo Grounds. Willard Marshall, the scouting director of the hated New York Giants, asked me if I was interested in signing a class D contract. I was thrilled by the offer, but college was in the offing. As a minor leaguer in the Braves organization (61-63 ) the only guys I followed in the Sporting News were Tommy Davis, Koufax, Joe Torre, Bobby Aspromonte and Joe Pepitone, all Parade Grounds alumni. While playing for the Yakima Bears in ‘62 in the Northwest League, I realized that Tommy was having an incredible year with the Dodgers! .He looked like the second coming of Willie Mays! Another great year in 63’ and then the devastating broken ankle injury. What a tragedy! The lack of recognition and the gross underpayment of Davis was emblematic of the way ball players were treated before the monumental efforts of Marvin Miller and Curt Flood! I wish today’s MLB players were more aware of the history! The fact that Tommy hung around the major leagues for another 13 years, shuttling from one club to another is testament to the toughness and resiliency he developed back in Brooklyn on the hardscrabble fields of the Parade Grounds. Best, Jerry On Saturday, every major-leaguer will wear No. 42, to commemorate Jackie Robinson, the first African-American in the majors in the 20th Century.

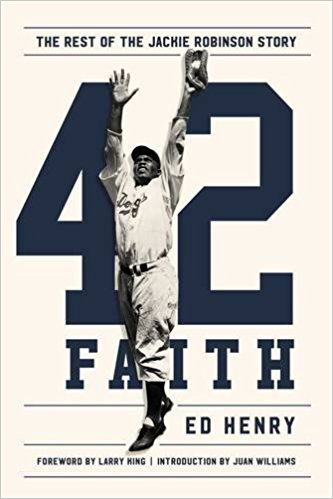

This will be the 70th anniversary of Robinson’s debut in Ebbets Field, Brooklyn – the beginning of a grueling season, a grinding decade. Jackie Robinson would die at 53. Many people think the ordeal heightened his diabetes, hastened his death. In a real way, he gave his life for a cause. This sense of Robinson as vulnerable point man for equality is never more relevant than in a time when Americans seem to be questioning their direction – when the Roberts Supreme Court can negate previous civil-rights legislation, letting us know that things are just fine now, we don’t need all those rules bolstering people’s rights to vote. By some cosmic happening, the Robinson anniversary and the return of baseball take place in the spring, in the time of Passover and Easter, celebrations of survival. Robinson’s own beliefs – the power that kept him going – is currently explored by Ed Henry in his new book, “42 Faith,” published by Thomas Nelson. Henry is the Fox News Channel chief national correspondent (and a friend of mine.) Henry is too young to have seen Robinson play or meet him but in his busy life he has admirably sought out people and places where Robinson’s history can be felt. Henry explores the magnetic pull of the ball park that used to be in Flatbush; the vanished hotel in Indiana where Branch Rickey gave shelter to the black catcher on his college team, the still-standing Chicago Hilton where a wise Dodger scout named Clyde Sukeforth interviewed a Negro League player named Robinson. Holy places, in a way. The story has been well told by Arnold Rampersad and Steve Jacobson and Roger Kahn, if not with this overt angle on faith: Robinson was a mainline Protestant who relied on his pastor, who taught Sunday school, who saw life through a framework of Christianity. He was sought out for the Brooklyn Dodgers by Branch Rickey, a man of religious dedication – who did not go to the ballpark on the Sabbath -- who had no qualms about wheedling his best players out of a thousand here, a thousand there. Aging Brooklyn heroes like Carl Erskine and Vin Scully recall the strength and complexity of Robinson, and aging fans recall the example of Robinson holding his natural fire, to establish himself, and his people. This was a big deal, the coming of Jackie Robinson. I remember being home in the spring of 1947 when my father called from the newspaper office to say that our team, the Dodgers, the good guys, had just brought up Robinson from the Montreal farm team, that he would open the season in Brooklyn. We (white, liberal) celebrated. Every year the major leagues celebrate with No. 42 on every uniform. Thanks to an inquiring journalist, the story goes on. I always thought Chaim Tannenbaum was from Quebec. He was the lanky male presence behind the beloved Kate and Anna McGarrigle, instrumentals and passionate tenor – particularly singing the lead on “Dig My Grave.” Talk about soul: Chaim Tannenbaum, singing gospel. One night the sisters decamped in Symphony Space or Town Hall or somewhere, and Chaim was nowhere to be seen. The sisters sang a song or two before a fan shouted lustily, “Where’s Chaim?” The ladies shrugged as if to say, deal with it. Maybe Chaim had a philosophy class to teach at Dawson College in Montreal. That was his day job. Kate passed in 2010 and the torch is carried by Loudon, by Martha, by Rufus, in their ways. And at the age of 68, Chaim released his first solo CD, “Chaim Tannenbaum,” last year. Never too late. One of his songs is “Brooklyn 1955,” about, you know, Next Year. Turns out, Chaim is from Brownsville. Who knew? We fans thought Next Year would never come, but the Brooklyn Dodgers beat the dreaded Yankees in that World Series and bells rang all over the Borough of Churches. (I can attest; I was in a soccer match in Brooklyn that afternoon.) In this tribute, Chaim strums and sings about the hallowed Dodgers long before pre-hipster Brooklyn, catching the mood of a borough finally having its moment. He’s been in Montreal for decades, and his Brooklyn history is a bit vague: people were already committing white flight in the early ‘50s, and Brownsville is not the total hellhole he describes. But he is right. Brooklyn, 1955, was a time and a place. Stick with the video because at the end the great Red Barber recites the defensive lineup from the 1952 World Series -- my eventual friend George Shuba in left, plus Billy Cox, “The Hands,” at third base. And Barber promises that sometime that afternoon the fans would be “tearing up the pea-patch” in Ebbets Field, one of his signature phrases -- a southerner talking about a pea-patch. In Brooklyn. (Below: Young Chaim Tannenbaum sings “Dig My Grave,” a cappella, 1984, Red Creek Inn in Rochester N.Y. with Anna McGarrigle, Kate McGarrigle and Dane Lanken, bass vocal.) We were driving through upstate New York and I saw a sign for Oriskany Falls.

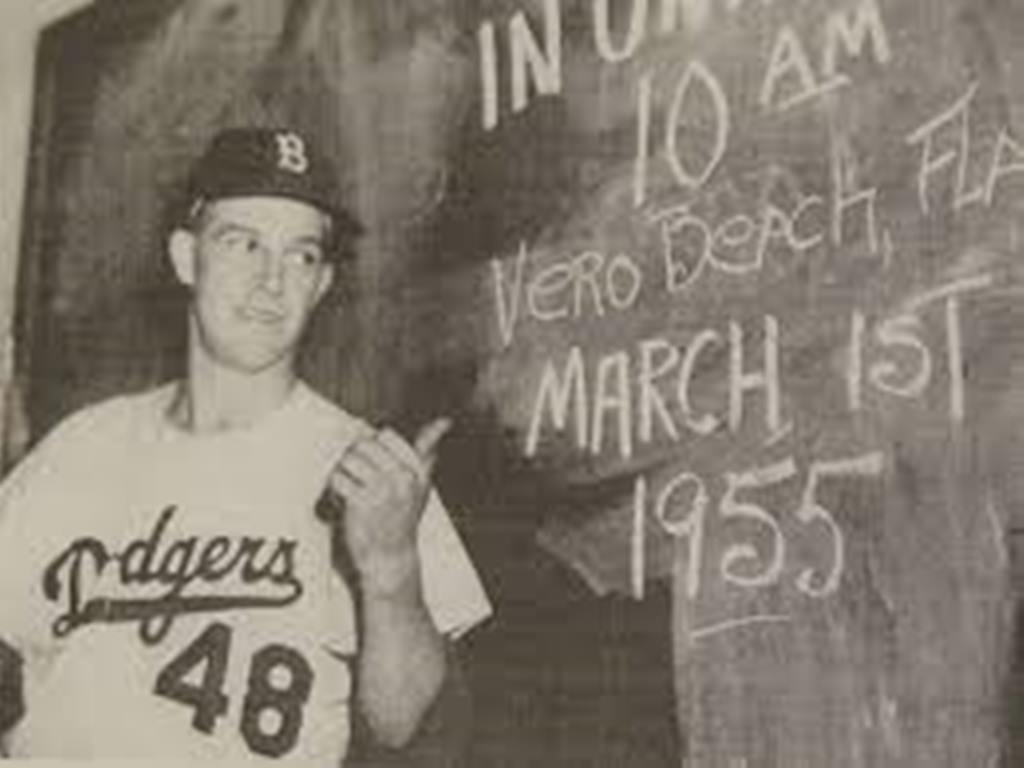

Right away, I flashed to a ball park in Brooklyn on the last day of the 1954 season, the Dodgers and Pirates playing out the string. Before Sandy Koufax became Sandy Koufax, before Clayton Kershaw was invented, there was Karl Spooner. I was there, one of 9,344 fans. A lefty from the minors, who had shut out the hated Giants on Thursday, came back and shut out the Pirates on Sunday. Eighteen innings in his first two games. Seven hits. Twenty-seven strikeouts. No runs. One of the best two-game debuts in major-league history. As my friend and I took three subway lines back to Queens that day, we envisioned the career ahead for Karl Spooner. As Brooklyn Dodger fans always said, wait til next year. Next year arrived, and Spooner had an 8-6 record, and the Dodgers finally won a World Series. But he had already blown out his shoulder in spring training of 1955, and never again pitched in the majors. Nowadays, there might be an operation for it, but by 1958, he was retired and living in Vero Beach, Fla., the training base of the team that had just deserted us. He died in 1984 at the age of 52. I ascertained via the Internet that a ball field is named for Spooner in Oriskany Falls, so my brother and I made a detour and asked a nice man at the filling station for directions. “I saw him pitch in 1954,” I said. I asked whether people in town still remembered Karl Spooner, and he said a few. I did not ask for their names or numbers; I had my own memories. We found the field down the hill. This being America in 2014, nobody was on the ball field – no league game, no kids playing choose-up, no game of catch. There was a modest sign, painted in Dodger blue, and on the other side facing the field is a resumé of Spooner’s career, from childhood to Ebbets Field. The records were compiled by Dr. Rich Cohen. “My friend, my doctor,” said my kid brother Christopher Vecsey, a professor at Colgate University. They umpire Little League games together, and every spring they gambol in a game of town ball, the ancestor of modern baseball. Dr. Cohen has also written a lovely biography of Spooner for SABR: http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b6f00e89 My brother said he might take his grown son, who still pitches in an adult league, to this field. He can imagine his son taking aim at the short porch in right field. I strolled out to the mound and approximated a left-handed delivery, in homage to the man I saw pitch in 1954. I spent a lovely day in Brooklyn on Wednesday. As soon as Mike From Whitestone turned downhill, I felt the surging image of Duke Snider slugging the ball over the screen and into Bedford Ave.

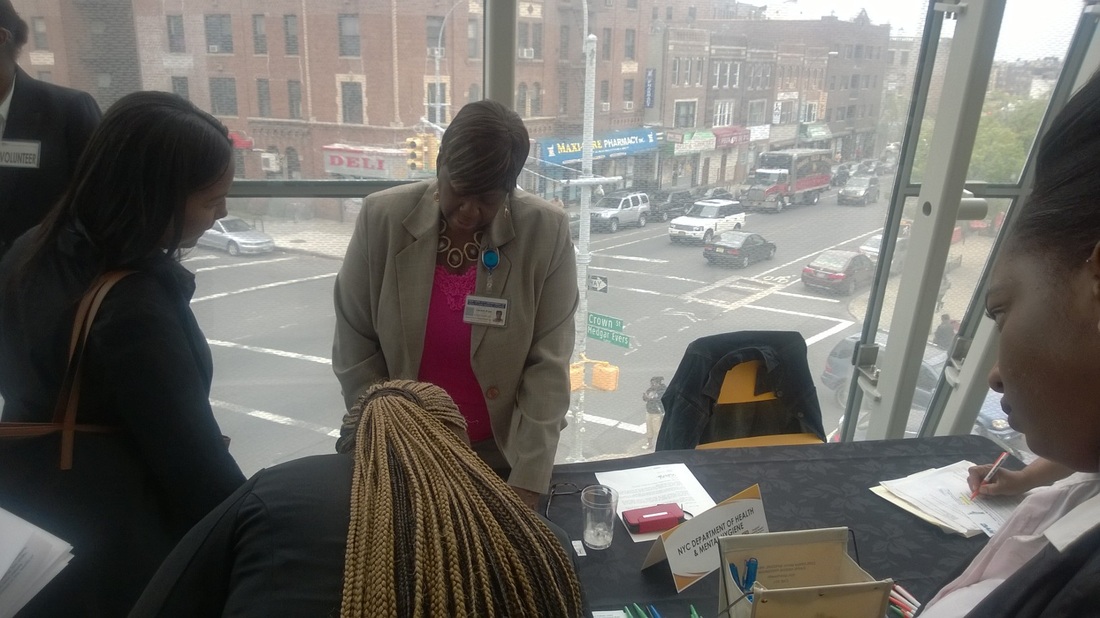

Mike parked near McKeever Pl. and I could feel my head swiveling like a compass needle to the apartment buildings where Ebbets Field used to be. But I was the only person talking about the Brooklyn Dodgers, about ancient history. The occasion was a career expo at Medgar Evers College, where several hundred very qualified students were seeking leads on jobs, on futures. I heard about the expo through Monica and Miguel Mancebo of Selective Corporate Internship Program (SCIP), which does such a fine job of preparing young people for the job market. The students saw my soccer book on the table and wanted to talk about their sport. One young woman from Trinidad plays defender for the Medgar Evers team; another young woman roots for VfB Stuttgart, from her home town; a volunteer told me she roots for Barça and her husband roots for Real Madrid. And Michael Flanigan, the director of development and major gifts officer at Medgar Evers, told me how he referees soccer matches in his spare time. I marveled at the résumés of the Medgar Evers students, their life stories, their work experience. Many of them have worked in kitchens, in day-care centers, in nursing homes. They see it as paying their bills. I told them to be proud of their work; they were learning the process, the system. Many of them want to be doctors and teachers, accountants and, good grief, journalists. I wanted to hire them all. I hope by now somebody has. |

Categories

All

|