|

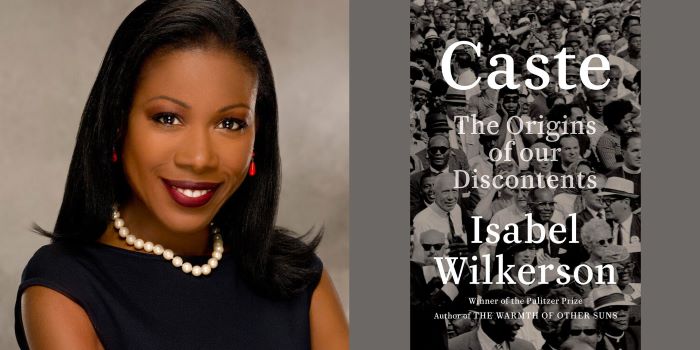

Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize when she worked for The New York Times. Later, she wrote a best-selling book about the great northward migration of Black Americans. In the process, Wilkerson earned a ton of airline miles, allowing her to fly first class much of the time. In addition to the few extra inches of space, Wilkerson was able to do research for her new book -- on the caste system in the United States. Even when she presented her boarding pass for Seat 3A, she was still treated as a stranger, a lower caste, as a female and as an African-American. Confused flight attendants stared at her and suggested she just keep walking to the back of the bus. Wilkerson also had to endure jostling for overhead-rack space from white male passengers. Anybody who is Black, or has friends and relatives of color, knows the drill. A few days after the 2016 election, Wilkerson settled into her first-class seat and noticed “two middle-aged white men with receding hairlines and reading glasses” who quickly bonded, with one stranger telling the other: “Last eight years! Worst thing that ever happened! I’m so glad it’s over!” The two instant buddies then celebrated from Atlanta to Chicago, assuming that the new President would be "good for businss." I am 100 percent positive that Trump's appeal to money guys helped advance the racism loose in the country. . Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” came out in mid-2020, before the little lovefest of assorted cut-throats and sociopaths and bigots and other Trumpites at the Capitol. I just caught up with “Caste” and found it compelling, as Wilkerson compares America’s enduring racial prejudice with the age-old caste system in India as well as the caste system that killed at least 6 million Jews and others regarded as untermenschen in Nazi Germany. Wilkerson points out how Hitler studied how whites in America marginalized and terrorized Blacks long after the so-called Civil War. Wilkerson also points out that contemporary Germany does not display statues and markers of the Hitler days, whereas the U.S. is only now coming to grips with Black youngsters having to attend schools named after Robert E. Lee, that old secessionist-slavemaster. It never went away. Wilkerson also presents dozens of examples of lynching and mutilation of Blacks, under slavery and long into the 20th Century, and still going strong in spirit. Trying to understand the American system in terms of the Indian caste system, Wilkerson flew overnight from the U.S. to London to attend an academic conference on caste, attended mostly by people of Indian ancestry, whether English or Indian or other nationalities. She immediately realized that the elite castes – even among academics -- were identifiable by lighter (Aryan) skin as well as a deep aura of entitlement, whereas members of the Dalit (Untouchable) caste – even with doctorates and other professional titles - - were of darker skin and reserved demeanor. She became friendly with a highly educated Dalit at the conference who described how his sister had cried about her dark skin when it was time to seek a husband. From her new friend, Wilkerson learned about Bhimrao Ambedkar, who renounced his Hindu standing and became a leader of the Dalits in the time of Gandhi. Her education about India will surely be the reader's education. As I read Wilkerson’s book, I thought about the new demographics in the U.S., as it heads toward a “minority” majority in the next decade or two. The white terrorists who stormed the Capitol in January are quite likely feeling marginalized by the talented and poised people of color who have become more evident in recent years. Some kind of change was gonna come -- or so some of us thought. It's been in the public consciousness for decades -- with the great Sidney Poitier embodying a possible new era in the 1967 movie ”In the Heat of the Night." For other examples, Wilkerson mentions the intelligent and handsome and poised couple that lived in the White House from 2009 to 2017, plus examples of changing America all over public life. As the pandemic endures, I gain information on the evening news from professionals like Dr. Kavita Patel of Washington, D.C., Dr. Vin Gupta of Seattle, Dr. Lipi Roy of New York and Dr. Nahid Bhadalia, with their kind and patient faces, with their knowledge and passion. The international look of today’s medical experts reminds me of that very good movie, “Gran Torino,” when Clint Eastwood, an auto worker with dark secrets from his military service in Korea, meets his new physician. (I'll never forgive Eastwood for his ugly televised rejection of Barack Obama, but his movie shows the growth of an aging bigot in a changing Detroit.) Last week, on MSNBC, Lawrence O’Donnell presented the viral immunologist who helped develop the Moderna vaccine -- -- Kizzmekia Shanta Corbett, Ph. D., who turns 36 on Jan. 26. Dr. Corbett saw the code for this new virus as it popped in from China, early in 2020, and linked it, in her mind, with anti-virus codes available here -- “over a weekend,” apparently. The rapport was clear between Dr. Corbett and O’Donnell, who is proud of being of Irish descent in Boston, and is one of the most open champions of African-Americans in public life. However, at the same time, a huge swath of white Americans is acting out in public, scorning vaccinations and masks, storming the Capitol a year ago, yelling racial insults at police while trying to brain them with heavy weapons. Many white Americans grew up thinking they had an edge over anybody with darker skin. Isabel Wilkerson’s powerful book points out the growing strains on the old American caste system. * * * Dwight Garner, one of my favorite writers at the NYT, reviewed “Caste" in July of 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/31/books/review-caste-isabel-wilkerson-origins-of-our-discontents.html Lawrence O'Donnell's interview with Dr. Corbett -- real life, not a movie: Colin Phelan is 23, a writer and teacher in Massachusetts, a recipient of a Fulbright-Nehru scholarship to India next year, and a friend of a family close to us. Our friend raved about his website, so I volunteered to take a look and was knocked over by what he knows, what he cares about. Back home in the States during the pandemic, Phelan has not lacked for adventures – taking his bike across country, going into Great Sand Dunes National Park in Colorado as fearsome sand tornadoes swirled ominously ahead, and so on. Passing through St. Louis, he discovered a World Chess Hall of Fame – who knew? -- and perhaps because he gets hammered by his students in their early teens, he explored the museum. Of course, he did. The exhibits fascinated Phelan with the various themes of chess sets around the world, and he also began to understand the role India played in the worldwide popularity of chess.  Phelan's blog also links warfare and chess, comparing the chess tactic of dominating the flank to one of the key moves of the Battle of Gettysburg, on July 2, 1863 -- how a professor from Bowdoin College in Maine, Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, told his troops to fix bayonets and rush downhill, into what became the gruesome but decisive Battle of Little Round Top. (Phelan caught my interest because, in my three years of college ROTC, Gettysburg was still being used as a key lesson in battlefield tactics, now of course outmoded, but still an object lesson in planning and reacting. I have walked the battlefield with our grandson George, who lives not far away. I recommended that Phelan read the magnificent restored first section of the novel, “O Lost,” by Thomas Wolfe, which takes place north of Gettysburg, a few days before the battle.)  Anthony Bourdain after dining with President Obama at Bun Cha Huong Lien in Hanoi, May 23, 2016. Anthony Bourdain after dining with President Obama at Bun Cha Huong Lien in Hanoi, May 23, 2016. Phelan has done most of the teaching in our interchange. His blog includes copious photos of chess sets from around the world – including a fruit-and-vegetable set – as he veers into an appreciation of Anthony Bourdain’s lust for life: “As a devotee to Anthony Bourdain’s ability to discover culture and companionship through food, I’ve for long tried to discover another means through which people wedged apart by language or other barriers can not only coexist, but catch glimpses of another’s personality and being,” Phelan wrote. I would not have expected poor Bourdain to pop up in a riff on chess, but there he is. Colin Phelan is living at a fast clip, so many interests and observations and opinions. Phelan has already had adventures on his first visit to Kolkata and Delhi, teaching English, learning the local languages. Now he’s back in the States for a school year, having adventures. Nice to be 23. * * * I have not begun to explore all the corners of this website. Please explore and enjoy: https://www.colinephelan.com/post/from-chaturanga-to-chess-successful-cultural-transmission-or-lost-in-translation  Like many people during the pandemic, we have been eating at home for well over a year – not hard duty for me, since my wife is a great and adventuresome cook. She’s mostly cooking and eating vegetables these days, cutting back on meat and dairy to combat allergies. That’s great with me, since I’d rather eat vegetables than meat, generally. I watched her prepare lunch today, noticing how many steps it takes to cook vegetables. (How astute on my part.) While she cooked, I did some scut work around the kitchen – and had time to free-associate with each dish, and the memories attached to them. 1. Okra Past. Soft and fresh, mixed with crispy breadcrumbs doused with an almond-milk version yogurt, in olive oil. The sight of okra brought me back to a friend many years ago, who had a house in rural Appalachia. The kitchen faced south to a sunny patch where two different crops grew right outside the window, plenty of sun. One crop was not my department. The other was okra, which he cut from the vine without having to walk outside.  2. Walnuts Past. In another pan, my wife mixed walnut pieces with onions and mushrooms, sprinkled with natural sugar. Why walnuts? She told me that on one of her child-care runs to Bangkok, she and colleagues would visit the outdoor markets and restaurants, in the relative cool of late evening. You could also purchase fish or meat, whatever vegetables you wanted, and a chef would toss it together in a wok, right in front of you. She said another stall specialized in shelled walnuts in a sweet sauce. My guess is, from memory, she aced it.  3. Corn on the Cob Past. Nothing makes me happier about summer than the arrival of fresh Long Island corn. While I chomp away, I think back to hot summer evenings while our father was at work: Mom would take our large family to Cunningham Park (in Queens), a few blocks up the steep glacial hill. We would carry a dozen ears of corn, or maybe two dozen, and commandeer a vacant fireplace and bench in the shade, and start a fire, and fetch water and boil the corn. My wife also has corn memories. On Sunday she nuked fresh corn in the microwave, but other times she twirls them over a flame, scorching them slightly, and sprinkling them with paprika. An Indian friend taught her that here on Long Island, but my wife also ate corn during her 14 child-care trips to India. She has memories of meals in affluent homes as well as shacks in the slums, where people shared whatever they had. (The Web says corn – maize – is mostly ground up for flour in India, but my wife set me straight: maize is also street food, strongly spiced, from stands in busy marketplaces – part of the life she came to love on her trips to Pune and Mumbai and other cities. Food is more than vibrant tastes on our tongue; food can be a Proustian reminder of seasons past. * * * Got any vivid memories of food in other places and times? Please share. ### The Chelsea-Manchester United match from frigid London put us in the mood for a taste of home.

We drove out to to the House of Dosas in the Indian enclave in Hicksville. Nobody was wearing Giant or Patriot gear. My wife waved at a little girl at the next table. She waved back, with a gold bracelet glittering on her tiny wrist. We had bhel puri, eggplant curry and rice, plus poori and potato masala, and my wife had spiced tea afterward. The waiter confided that they had just sent out for their own lunch – pizza, for a change of pace, he said with a laugh. We were now fortified for the long evening ahead. What a country. Do the rest of you have this reaction? I walked into a Staples store on Sixth Ave. and 23rd St. in Manhattan Thursday night, needing a few mundane items

I was helped by five – count ‘em, five – nice people with smiles and time and knowledge. One young woman met me at the door, pointed me in the right direction. One clerk dug out a 2012 datebook from a bottom shelf and another fitted refills for several pens, hardly big-ticket items and all requiring more than a few seconds of attention. And two cashiers could not have been more pleasant. Then I read Paul Krugman’s Friday column in The New York Times that Staples has a policy of hiring for service, rather than downsizing. Those polite and well-prepared people were not there by accident. I had the same experience on the phone the other night when I tried to cope with the hopeless non-instructions that came with a new HP printer. I was stunned to get through to Customer Support in Kolkata. The young man said “Calcutta,” the old Anglicized version, as if to reassure his grumpy caller, but we have a family affinity for India, and I knew I was in good hands. He talked me through the inscrutable process and the printer was humming in a short time. Meantime, we hear politicians braying about growing the economy, but the biggest fortunes seem to be amassed by entrepreneurs – no names mentioned -- who line employees against a brick wall and machine-gun ‘em down. I’m not good at the math, but my visceral impression is that I am going to give my business to companies that provide service, whether in person or from Kolkata. Doesn’t that make sense to you? _ The holiday mail brought photographs — American backdrops, Indian faces, in their late teens and early 20s. And in one card, news of a baby.

My wife refers to herself as The Stork because she used to fly with children, from Delhi or Mumbai, through taxing layovers in Europe, onward to American airports, to be greeted by family reunions. She would make her deliveries, then hop the next flight home, her stork work done. Marianne estimates that she escorted 30 children on 13 trips, sometimes with a companion, sometimes solo. Many of the families send photos and news — musical instruments, sports, graduations, weddings — and now a baby. The children, mostly girls, had been left in bus stations or on the steps of police stations, had been placed in orphanages, given the best treatment possible, offered first to Indian couples, and also treasured by Norwegian families, American families. We heard about the Indian children through Holt International of Eugene, Ore., which cares for children all over the world. Our contact, our friend, Susan Soonkeum Cox, arranged for me to visit a center outside Seoul, during the 1988 Olympics, to visit a man we’ve been supporting for decades, since he was a child. Susan later asked if I’d be interested in volunteering as an escort, and I said I thought my wife would be good at that. Marianne was more than good. Not only did she love India from her first minute, but she also became involved with an orphanage in Pune, sometimes called the Oxford of the East. She watched the skilled officials and workers, and sometimes jumped in where she thought she was needed, learning from Lata Joshi and other friends and officials there. One judge was balking at allowing adoptions because of rumors that children were used as servants in America. Somehow Marianne got an appointment with the judge and displayed her photo album of healthy smiling children, in the bosom of America. The judge, to his credit, got the point. The orphanage needed a new building. Somehow Marianne convinced a farmer to make some land available for a new building, which is now in use. She could operate in India because she loved the people — Hindu and Muslim, Parsi and Jain, all the castes. She was invited to wealthy homes for lavish meals and shared modest lunches at women’s shelters in the slums. And always at the end, an armful of children, meticulously approved by Indian and American authorities. Stork time. I don’t know how she did it, carrying multiples of children from a year old to 8-9-10 years old, with bathroom issues, food issues, language issues, children who knew they were going to a new home, but first having to go through customs, waiting rooms, cramped airplane seats, the faces of strangers. Marianne's aunt Bettina knew some flight attendants on that great airline, Pan-Am, until its lamentable collapse at the end of 1991; many of them moved over to Delta. They sometimes upgraded Marianne to business class, where she cajoled German or Scottish or American businessmen to hold a crying child while she changed another baby’s diaper. Once she was forced to stay overnight at a Heathrow motel, with an infant and a 7-year-old. When they went down for the buffet in the morning, the older child could not believe there was that much food in the world. She sampled, she ate, she laughed out loud at her fortune. I went with Marianne once, on a trip that began with missions to Thailand and Vietnam. Seeing India through Marianne’s eyes was an adventure. She had the cadence and she had the words and she had the body language. She was home. Our trip back was from Mumbai through Frankfurt to JFK. I was given a healthy boy of 2 or so; we bonded in minutes, doing guy stuff — he grabbed my beard, I elbowed him gently, we wolfed down our meals, I nicknamed him Bruiser and was more than a little sorry he already had a family waiting for him in the Midwest. A French seeker, in a robe and sandals, coming back from an ashram, spelled me at times on the first leg. Marianne’s child had a high fever. The Pan-Am attendants upgraded them, helped ice him down and keep him hydrated. On landing in New York in the middle of the night we rushed him to the hospital, where a medical SWAT team jumped in — discovering an ear infection. A few days later, he was with his new family out west. He’s in college now. On Marianne’s last run to her beloved Pune, she and our older daughter, Laura, brought home one more child — our grand-daughter Anjali. But first there was a farewell ceremony with our friend Mrs. Joshi. The boy in the red outfit in the photo, snuggling up with Marianne? I asked her about him the other day. Oh, she said, he was deaf. Whenever she was in Pune, she always had a child in her arms. I’ve never found a way to tell the story of Marianne’s love of the children, her love of India. She should write a book about her 13 trips, but she says she’s an artist, not a writer. The holiday card, the news of a baby, brought it all home. The Stork is a grandmother now. |

Categories

All

|