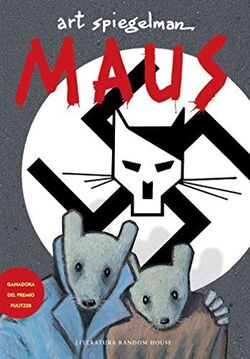

How strange, to be reading a book about the Holocaust while another slaughter takes place. For no good reason, I missed reading Art Spiegelman’s classic book, “Maus,” a graphic novel about his parents’ survival, of sorts, from Auschwitz. I always meant to read it since the first part was published in 1986, but just did not until now. However, when school boards and mayors and other American worthies began to ban this Pulitzer-Prize winning book as too controversial for young people, I realized I had to join the millions who had read it. I tried to take it out from the wonderful Nassau County library system only to discover I was 31st in the electronic waiting line – but fortunately there was a Spanish-language copy available from a few towns away. With my moderate Spanish and a handy dictionary – and the graphic panels displaying cruelty and hope – I read it. Meanwhile, a latter-day Hitler has decided to take over a neighboring people, even if he has to kill thousands, maybe millions, of them – “Man’s inhumanity to man,” to quote the Robert Burns poem, all over again, "a boot stamping on a human face – forever," in the words of George Orwell. Art Spiegelman was documenting it decades ago, as his aging father began to tell how the world fell apart in the late 30s in Poland, when the Nazis were flexing their muscles and most locals were none too hesitant to cooperate. Chapter by chapter, Spiegelman portrays himself, already an adult cartoonist with a political bent, getting his widower father to tell the story of his courtship and marriage and the inexorable plodding toward Auschwitz, followed by a reunion of the parents and the path to Rego Park, Queens, and the Catskills in the summer – heaven on earth, sort of, for people who have lived in Nazi hell. The artist portrays Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs, the British as fish, the French as frogs, and the Swedish as deer. What would the Russians be, if and when we get to a similar re-telling of this horror? Perhaps, lumbering, dim-witted bear cubs, with an old and rabid bear sending them off to mutual slaughter, up against a Ukrainian people with a (Jewish!) hero/president, trying to rally the world. As the father talks to his son, he tells how he and his wife went underground, surviving with the help of the occasional kindly Pole, and then how they survived in adjacent camps, he by being fluent in English and German as well as Polish – and learning skills that make him valuable to the warden, who feeds him, protects him. The father tells of death, step by step, of men around him. It’s a horror show, but also a testimony to the will to live – now being seen by Ukrainians who fight bravely for what is theirs, while many elderly and children are sent to relative safety. Spiegelman’s masterpiece is worth finding – buying -- and assimilating. In “Maus,” people are flawed, one way or the other, but the urge to survive against the wicked is strong. For the people of Ukraine, my heart goes out. I was trying to figure how to express thankfulness, and fortunately others have done it for me.

On Wednesday’s editorial page of the New York Times is a lovely essay by Tish Harrison Warren, an Anglican priest. (“This Year, Exercise Your Thankfulness Muscles”) Her fifth and last suggestion was “Take a gratitude walk,” about her young daughter who “invented something called the Beautiful Game,” finding sights that touch the heart. My responses to her essay: SIGHT 1: Fall Colors: I lifted my eyes off the printed page and saw the northern sky outside our home, with autumnal trees. Even though some people are figuring out that trees are vital in the struggle to save the planet, trees nevertheless are under attack in traditionally leafy suburbs like ours. The Town of North Hempstead, which pretty much allows leaf blowers and tree choppers to spew gas fumes and dust, making our suburb feel like an airport runway, is fretting over trees getting lopped off. These privacy-giving autumnal colors above are on our property, and we are grateful. SIGHT 2: A Young Nurse: The other day I had a common procedure as an outpatient at Glen Cove (Northwell) Hospital. The young nurse who prepped me was getting married – three days later. When they shooed me out a few hours later, I could still remember, over her mask, the glow of her eyes. I was thankful for skill, and youth, and hope. SIGHT 3: A Crowded Restaurant: The other evening, I took a walk around our town and slowed down outside Gino’s on Main Street. Since my wife sussed out the pandemic early in 2020, in our caution, we have not eaten out – not a terrible loss because she is such a good cook – but there are familiar places we miss in our town: Diwan on Shore Rd. and DiMaggio’s on Port Blvd. and Gino’s. I peeped in a side window at Gino’s and saw every table and every booth filled, the staff moving fast, and I hallucinated about a Gaby’s salad and a daily special and those hot chewy rolls and the cheesecake a la nonna for dessert. We’ll be back soon, I keep saying, but in the meantime I am thankful for the bustle at Gino’s. SIGHT 4: Books About Thanksgiving. I am currently reading “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer, about very different strains of English immigration in the New World. I never fully understood what it meant for settlers to call their new home New England – but as I watch a very divided country display major stress faults, I am more thankful than ever for the “New England” emphasis on education, producing a high level of literacy and study. May it prevail. As the U.S. Thanksgiving loomed, I took another book off our shelves, “Mayflower,” by Nathan Philbrick, who tries to re-create the fall of 1621: We do not know the exact date of the celebration we now call the First Thanksgiving, but it was probably in late September or early October, soon after their crop of corn, squash, beans, barley, and peas had been harvested. It was also a time during which Plymouth Harbor played host to a tremendous number of migrating birds, particularly ducks and geese, and Bradford ordered four men to go out “fowling.” It took only a few hours for Plymouth’s hunters to kill enough ducks and geese to feed the settlement for a week. Now that they had “gathered the fruit of our labors,” Bradford declared it time to “rejoice together…after a more special manner.” The term Thanksgiving, first applied in the nineteenth century, was not used by the Pilgrims themselves. For the Pilgrims a thanksgiving was a time of spiritual devotion. Since just about everything the Pilgrims did had religious overtones, there was certainly much about the gathering in the fall of 1621 that would have made it a proper Puritan thanksgiving. But as Winslow’s description makes clear, there was also much about the gathering that was similar to a traditional English harvest festival—a secular celebration that dated back to the Middle Ages in which villagers ate, drank, and played games. Countless Victorian-era engravings notwithstanding, the Pilgrims did not spend the day sitting around a long table draped with a white linen cloth, clasping each other’s hands in prayer as a few curious Indians looked on. Instead of an English affair, the First Thanksgiving soon became an overwhelmingly Native celebration when Massasoit and a hundred Pokanokets (more than twice the entire English population of Plymouth) arrived at the settlement and soon provided five freshly killed deer. Even if all the Pilgrims’ furniture was brought out into the sunshine, most of the celebrants stood, squatted, or sat on the ground as they clustered around outdoor fires, where the deer and birds turned on wooden spits and where pottages—stews into which varieties of meats and vegetables were thrown—simmered invitingly. In addition to ducks and deer, there was, according to Bradford, a “good store of wild turkeys” in the fall of 1621… The Pilgrims may have also added fish to their meal of birds and deer. In fall, striped bass, bluefish, and cod were abundant. Perhaps most important to the Pilgrims was that with a recently harvested barley crop, it was now possible to brew beer. Alas, the Pilgrims were without pumpkin pies or cranberry sauce. There were also no forks, which did not appear at Plymouth until the last decades of the seventeenth century. The Pilgrims ate with their fingers and their knives (117-118). * * * I am also thankful for readers of My Little Therapy Site, who contribute so much. Coming soon after Diwali, and with Chanukkah and its celebration of life following so closely, can you share any thoughts about thankfulness? * * * (With thanks to the website Reformation 21, Lancaster, Pa., for the excerpt from the Philbrick book: https://www.reformation21.org/about-reformation21 With thanks for the essay by Tish Harrison Warren: www.nytimes.com/2021/11/21/opinion/thanksgiving-gratitude.html?searchResultPosition=1ition=1  Clint Smith at Monticello Clint Smith at Monticello I just read a great new book: “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America,” by Clint Smith. Smith’s main point is that people, northerners and southerners, are now learning things about slavery they were not told in school -- the depths of depravity by which a female slave could be labelled a “good breeder” by her owners, and other aspects of good old-fashioned American enterprise. Many people in this country still see slavery through a sentimental haze: slaves were better off here than they would have been in Africa; they were handled benevolently at the plantations. You know, good people on all sides. Nowadays mayors and school boards and governors are trying to forbid controversial or academic critiques of America. (Some of these moronic governors are aiding Covid by not mandating vaccinations and masks at work and school.) Smith’s book about slavery lies is a companion to the so-called “Big Lie” about alleged election fraud and the merry tourists who flocked to the Capitol last Jan. 6. For all the chicanery and cowardice in high places, the worst parts of slavery are impossible to hide as Smith makes his rounds. As a one-time news reporter, I respect his shoe-leather approach -- visiting hot spots of the slave trade. A staff writer for the Atlantic – and a poet – Smith interviewed tour guides and museum directors as well as tourists, plus participants in Confederate commemorations. The new cadre of historians and guides make it clear that that people, white people, mostly male, not only performed violent deeds but also knew what was being done, mostly in rural and southern states. Smith begins where, in a sense, the country began – Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, where he "owned" slaves while preparing to write the Declaration of Independence. While he put pen to paper, his white staff put whips to the backs of Black slaves. Background music for Jefferson. At Monticello, Smith chats with two visitors -- white, Fox-watching, Republican-leaning women, who hear a guide talk about Jefferson’s long association with a female slave. Speaking to Smith, who is Black, the two women seem aghast. Smith quotes one of them: “’Here he uses all of these people and then he marries a lady and then they have children,’ she said, letting out a heavy sigh. (A reference to Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, who bore at least six of Jefferson’s children. The two were never married.) ‘Jefferson is not the man I thought he was.’” That is the theme of the book – many Americans in position of responsibility and knowledge deliberately deflected what was known about slavery. And not just in the South. I know somebody who did college research on commerce in New England, and never came across the mention of slaves in Yankee states. Then again, in a 2020 farewell to the great John Thompson, I praised a recent book about Frederick Douglass and noted that in all my school years in New York (with many history electives in college), I never heard the name "Frederick Douglass." (To be clear, I did know his name, just not from school. Our parents were part of a Black/white discussion group, and they extolled heroes like Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, and all of the children have learned from our parents.) Smith points out that the Dutch and English, who pushed out the Lenape natives, welcomed slaves on the oyster-laden shores of lower Manhattan, and used them for labor, and shipped thousands to farms and other towns. New York was the second largest entry port, distributing slaves culled from Africa. Those who died were tossed, unmarked, into a pit near Wall Street. One chapter in this book about slavery jarred me because I did not see it coming – a visit to the dreaded Angola Prison in Louisiana. Smith explains his visit to Angola by pointing out that Black prisoners worked for free or for pennies, at the penal equivalent of plantations. In fact, Angola had a big house, where the warden and his family were served by trusted Black prisoners. Prisons as plantations: As it happens, I have heard the metallic clank of the heavy door slammed behind me in three different prisons – and all three stories involved Black men. (See the links below.) Smith’s itinerary includes: Monticello Plantation, Va.; the Whitney Plantation, La.; Angola Prison, La.. Blandford Cemetery, Va., Galveston Island, Tex, where emancipation was belatedly revealed to Blacks, leading to the recent proclamation of a new national holiday -- Juneteenth; New York City; and Gorée Island, Senegal, the legendary focus for the African slave trade. In a moving Epilogue, Smith interviews his own elders for stories of prejudice, slavery and downright brutality they experienced or heard from their own elders. Clint Smith’s book makes it clear that white America knew more about slavery than it discussed -- just as many of our "public servants" like to talk about sight-seers who had a fun day in the Capitol last Jan. 6, brandishing flagpoles, gouging eyeballs and shouting racial epithets. It never went away. It’s who we are. * * * Two book reviews in the NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html Three of my stories from prisons, when I was a news reporter: https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/09/archives/frazier-sharp-in-tough-prison-talk-show-frazier-sharp-as-he.html https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/02/archives/new-jersey-pages-a-scholar-in-the-new-alcatraz-felon-finds-himself.html https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/12/archives/carter-reacts-stoically-to-denial-of-new-trial-i-hope-im-still.html * After writing this piece, and reading the thoughtful comments, I discovered a new book: “Land,” by Simon Winchester, a writer with great and varied interests. (We met in 1973 when he was posted to Washington by The Guardian.) Now living in the U.S., Winchester is writing about the creation and development of land.

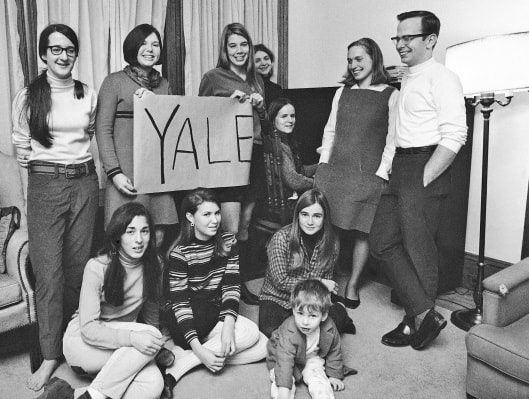

An early paragraph about the original inhabitants of this continent fits right in with the tone of this discussion: (Page 17) “The serenity of the Mohicans suffered, terminally. The villagers first began to fall fatally ill – victims of smallpox, measles, influenza, all outsider-borne ailments to which they had no natural immunity. And those who survived began to be ordered to abandon their lands and their possessions, and leave. To leave countryside that they had occupied and farmed for thousands of years – and ordered to do so by white-skinned visitors who had no knowledge of the land and its needs, and who regarded it only for its potential for reward. The area was ideal for colonization, said the European arrivistes: the natives, now seen more as wildlife than as brothers, more kine than kin, could go elsewhere.” Winchester’s newest book then goes in many directions. I look forward to reading the rest. I just read a powerful book about the first class of women at Yale University – in the fall semester of 1969.

Yale, bless its crusty old heart, managed to enroll female students who were more than up to the academics of the great university, but also quite able to speak up – and act up -- for their rights. It was the 60’s, after all. That tumultuous year of 1969 is the backdrop for the book, “Yale Needs Women: How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant,” by Anne Gardiner Perkins, who arrived at Yale eight years after the first female undergraduates. After years of pressure, Yale finally joined many all-male schools that had accepted women, however imperfectly. Given the limit of 230 spots for women (along with the usual 1,000 spots for male freshmen, all regarded as “leaders”) the admissions department did a fine job, finding women with talent and guts to go along with the brains. Many pioneers depicted in the book do not come off as stereotypical silver-spoon, prep-school graduates but rather the best and brightest from all over – rock stars in their way, with the spirit of Tina Turner and Grace Slick and other icons. In Perkins’ book, these women are as diverse as any admissions director would dream: Among my favorites are Connie Royster, boarding-school grad, actor, African-American, worldly, teaching her instant good friend, Betty Spahn, white, from the Midwest, how to handle chopsticks; Kit McClure, from a New Jersey suburb, talking her way into playing her trombone on the all-male marching band, later cutting much of her red hair and helping form a rock band with a powerful feminist soul. Another pioneer was Lawrie Mifflin, who forced Yale to start a field hockey team – with real uniforms! with a real field! With a real coach! Lawrie became a journalist after shaming the all-male Yale Daily News into covering female sports. She later became a deputy sports editor at the Times -- and a good friend of mine -- and is today the managing editor of “The Hechinger Report” and was recently honored by Yale for her many accomplishments. Not all the women were activists at heart, but most were pushed into action by conditions: no locks in the bathrooms, not enough security at the dorms or around the campus, hardly any female teachers or administrators, and the feeling of being patronized in the classroom while also being hustled for dates (and more) by male students -- and male teachers. (The university still bussed in women from all-female schools, a long tradition.) Fortunately, the women had a champion in Elga Wasserman, with a doctorate in chemistry, who was appointed a sort of dean of women – but without the title, without the power. Wasserman fought for the women, minute by minute, but was eventually seen as a problem by the patrician president, Kingman Brewster, Jr. Two other heroes were a couple, Philip and Lorna Sarrel, he a gynecologist, she a pediatric social worker, who worked as a team to offer medical services and counseling, so much in demand that their one lecture class on sexuality was attended by over 1,000 students – women and men. Facing difficulties they probably could not have imagined, the women demonstrated, infiltrating clubby bastions, making the establishment aware of how things worked, and did not work. There was pain, including at least two rapes of women in the freshman class. Within the four years of their entry, the women had lobbied for more spots, challenging the quota of 1,000 male “leaders” who were accepted annually. Eventually, they achieved gender-free admissions, to the point of numerical equality today. Yale, being Yale, could attract these women -- and diverse men -- of excellence. On campus during the first four years of the pioneers were such future leaders as Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Janet L. Yellen, Kurt L. Schmoke and – sound the trumpets! -- from my old school, Jamaica High in Queens – Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, in her 13th term, now from Houston. Perkins has written a gripping guide on how to seek change in today’s world – as young people realize that our “leaders” are “leading” the U.S. in an assault on democracy and law, prejudices are seeping back, and young people face a future on a smoldering planet. The women of 1969 are admirable role models for all. * * * I mentioned the Yale book to my kid brother, Christopher Vecsey, a professor at Colgate University, which went coed a year after Yale did. Chris (he never tells me anything!) said Colgate held a symposium last April: “Women and Religion, Philosophy and Feminism,” featuring pioneers of 1970. Chris is also the editor of a book from the symposium: https://www.colgate.edu/news/stories/symposium-honors-professors-wanda-warren-berry-and-marilyn-thie * * * NYT review: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/13/books/review/yale-needs-women-anne-gardiner-perkins.html?searchResultPosition=1#commentsContainer NYT retrospective this fall: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/upshot/yale-first-women-discrimination.html I am thankful for the Wampanoags who flocked to the Plymouth settlement in November of 1621 when they heard white people firing off their guns, and stayed three peaceful days to partake of the “feast.” Nobody spoke of “thanksgiving,” but rather a celebration of survival. Tribal ways were more complex than most people today know; the Narragansetts in what became Rhode Island welcomed Roger Williams, banished from Massachusetts for his inclusive Christian beliefs. All the “Indians” deserved better than the genocide that was coming down on them. I am thankful for the Americans who arrived as slaves in shackles and were treated cruelly. I am thankful for the modern-day Africans who flee failed societies and continue to add talent and energy and spirituality to the United States. I am thankful for the Latino people in my part of the world, who do the hard work that immigrants always do. In recent months we have had painters, gardeners, plumbers’ assistants and a mason’s assistant around our house, most of them quite willing and skillful. Their children speak colloquial English and contribute in the schools; some are going to college – the American dream. I am thankful for the immigrants who served in the military, many of them on the promise of citizenship for their contributions. I am sickened by a country that welshes on its promises, both domestic and foreign. People come to America in hope, the way the “pilgrims” did, and their children are put in cages. I am thankful for some of the best and brightest in this country, who left their homelands, escaping the Nazis or the Soviets, for what America said about itself -- the promise of education and opportunities and honest government. I am thankful for the true believers who testified in Congress in recent days, speaking of their hope in America. Some of them are Jews, like Marie Yovanovich and Lt. Col. Alexander S. Vindman,, who served so diligently and speak so eloquently about this country. Lt. Col. Vindman acknowledged his father for bringing the family from Ukraine to America, saying: “Here, right matters.” They should put his saying on the next new dollar bills. For their pains, Yovanovich and Lt. Col. Vindman have heard sneering overtly anti-Semitic sentiments from some of the “patriots” in government. Shades of Father Coughlin in the ‘30s, Roy Cohn (Donald Trump’s mentor), with Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the ‘50s, and Richard Nixon blaming the Jews during his last days in the bunker in the ‘70s. In America, it never goes away. Finally, I am thankful for Dr. Fiona Hill, a non-partisan government expert on Russia, and an American by choice, a coal-miner’s daughter from Northeast England with a Harvard degree. (Having helped Loretta Lynn write her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” I heard Dr. Hill’s background and said, “They are messing with a coal miner’s daughter. Not a good idea.”) Dr. Hill caught everybody’s attention by speaking so knowledgeably in what sounded like the finest British accent to our unsophisticated ears but which Dr. Hill termed working-class. She besought the legislators not to swallow Russian propaganda. The Republican firebrands seemed to know they were outmatched; a few panelists scampered to safety. One of the remaining Republicans, Dr. Brad Wenstrup, R-Ohio, spoke of his non-partisan volunteer service as a doctor of podiatry in Iraq; it is also known that he administered to a colleague shot on a ball field, and rushed to a train crash near Washington. After delivering some remarks with a scowl, Dr. Wenstrup was not about to ask questions of Dr. Hill. After she requested the chance to respond, Dr. Hill produced the little miracle of the hearings: As Dr. Hill spoke passionately about fairness and knowledge, the anger drained from Dr. Wenstrup’s face. He was listening – he had manners -- he maintained eye contact -- and he seemed touched, perhaps even shocked, that she was speaking to him as an intelligent adult. How often does that happen in politics? “He’s going to cry,” my wife said. As Dr. Hill finished, she thanked Dr. Wenstrup, and he nodded, and we saw the nicer person behind the partisan bluster. (I am including a video, but nothing I find on line captures the ongoing split-screen drama that we saw in real time. Maybe somebody can find a better link of this sweet moment, and let me know in the Comments section below.) I am thankful for Dr. Fiona Hill’s educated hopes for a wiser country. I am thankful to Dr. Wenstrup for listening. I wish them, and Ms. Yovanovich, and Lt. Col. Vindman and all the other witnesses a happy and civil Thanksgiving. (In other words: Don’t yell at your cousin for not agreeing with you!) * * * (In the video below, you might want to skip forward 5 minutes or so, to the point where Dr. Hill asks, "May I actually...." . The video, alas, does not show the split-screen version.) It’s not the playoffs. It’s so much more. That’s the only way to think about the championship of Major League Baseball, grandiosely named The World Series.

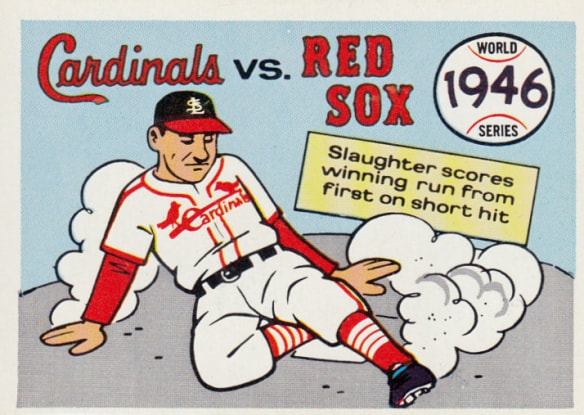

I love the World Series because it’s been around since 1903, albeit transferred from the sunlight of early October to the televised darkness of late October. The World Series deserves a sharp mental click of the brain when the league playoffs end and the World Series begins. It’s different. The Washington Nationals and Houston Astros are playing in the same event graced by Walter Johnson of the Washington Senators and Willie Mays of the New York Giants back in other days, when there were two distinct leagues, no playoffs, but two champions playing each other. Who will be the Country Slaughter of St. Louis racing home with the winning run of the 1946 World Series or Joe Carter winning the 1993 World Series with a walk-off homer for the Toronto Blue Jays? (I still call the 1946 World Series my favorite because it was the first one I noticed, age 7 -- players back from the war, Musial vs. Williams, two grand baseball cities, epic winning run.) World Series statistics exist in their separate category: Q: (Courtesy of my friend Hansen Alexander): What team has the best percentage of championships in the World Series? A: why, it’s the Toronto Blue Jays, 2-0, in 1992-93. Q: Which star is the first pitcher to lose his first five decisions in the World Series? A: As of Wednesday evening, it is the excellent Justin Verlander of Houston. (Not some palooka, but the two-time Cy Young Award winner with grass stains in an unusual place – on his name on the back of his uniform from diving for a dribbler Wednesday.) I heard that gloomy 0-5 statistic and immediately thought of the admirable Don Newcombe of my childhood team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, who had an 0-4 record in the World Series (all against the Yankees. The World Series is not merely part of the post-season. Do younger fans make that distinction? Or is it just another long and noisy event in the October TV calendar? Speaking of TV, I find it hard to watch these four-hour games, particularly with network breathless overkill of stats and story lines, bringing the world up to speed on these two teams. I am geared to the Mets’ TV and radio crews, speaking to knowledgeable home-team fans. To be fair, Ken Rosenthal and Tom Verducci have journalism credentials, and John Smoltz is an intelligent former star pitcher, but Joe Buck just wears thin, hour by hour by hour. It’s easy to root if you have a team in the World Series. Otherwise, there is a void. I was inclined to root for Houston – having fallen in love with that team that won the 2017 Series and is mostly intact, with alert and lean players who play the game the right way – and let the homers come as they will. I love Jose Altuve, my favorite non-Met. (Aaron Judge of the Yankees is second. I loved the clip of the two of them talking during the league series – 13 inches’ difference in height.) Plus, as a Met fan, I have come to think of Washington as an underperforming franchise, firing wise old managers like Dusty Baker and Davey Johnson, with sourpusses like Bryce Harper and Stephen Strasburg, but they let Harper walk last winter, and Strasburg seems to have matured, and the Nationals have, finally, jelled. There is one other factor to following the World Series when your team has long since scattered to the hinterlands – familiar faces. During Wednesday night’s marathon, I got an e-mail from my friend Bill Wakefield, who pitched for the 1964 Mets. He referred to “your guy,” meaning Asdrubal Cabrera, the wise old head who gave the Mets several seasons of skill and leadership and joyful noise. Cabrera was the one who ritually removed the helmet from the teammate who had just hit a homer. He made everybody better. Then he moved on. Cabrera was ticked last summer when the Mets did not bring him back for a stretch run, so he signed with the Nationals. He started at second base in the first two games in Houston (where the designated hitter rule is observed) and drove in three runs Wednesday. Root for “your guy.” Cabrera or Altuve? Either way, these two teams are adding to the lore and emotion and statistics of that very American stand-alone event called, you should pardon the expression, the World Series. It's amazing what you can find on line, from people you don't even know, who are updating ancestry information. New information pops up, virtually day by day.

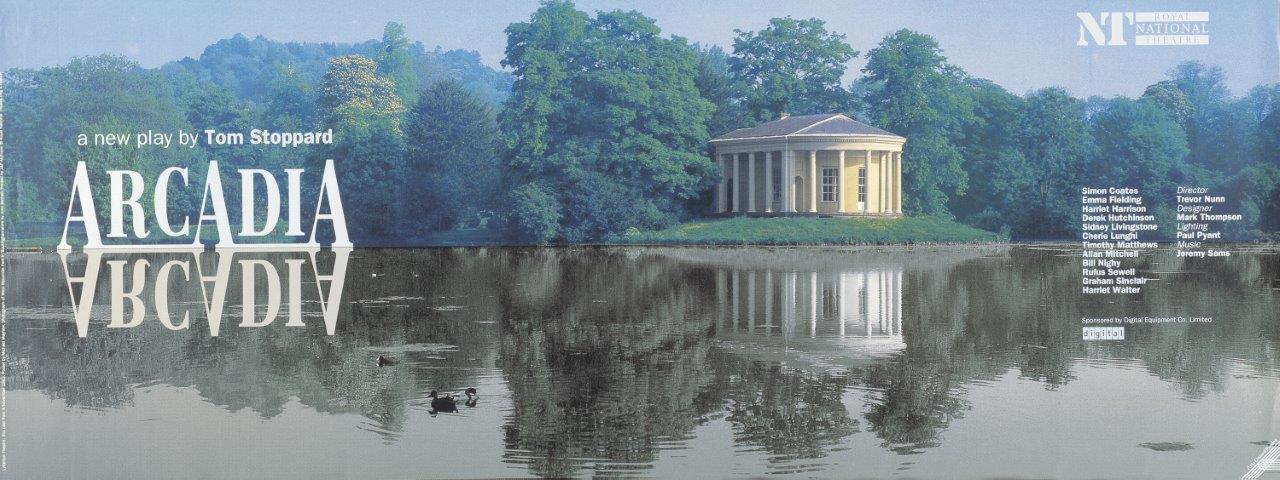

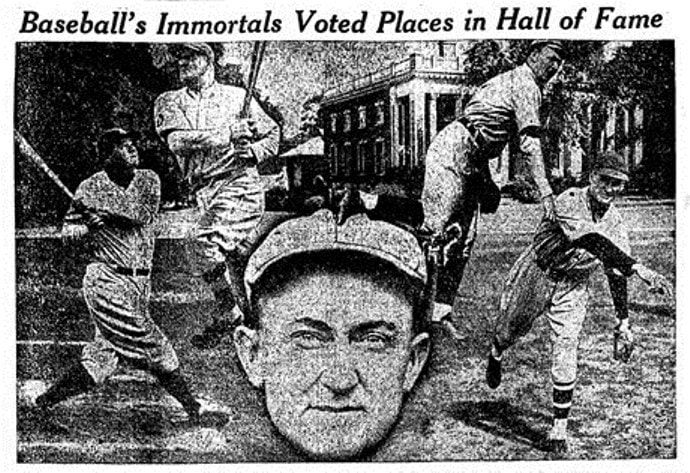

My wife and I were discussing her ongoing genealogy research of her maternal ancestors in Lancashire, England – so many relatives with the same names, from century to century. People with the same first and last names pop up in Manchester....or Liverpool....or Rhode Island....or Baltimore....or Kentucky.....or Australia....and some of them even back to England. She also researched my mother’s ancestry, in the same region -- centuries of women named Mary and Jane and Elizabeth (right out of the 16th Century history books) plus men named John and James and George. No direct links between families, at least not yet. We agreed there could be a play about the overlapping of the centuries – when suddenly we remembered that just such a play has already been written. “Stoppard!” one said. “Arcadia!” the other said. I refreshed my memory about "Arcadia," and the first thing I noticed was that the playwright, Tom Stoppard (Born Tomás Straüssler on July 3, 1937 in Zlín, Czechoslovakia) is having a birthday soon. Happy birthday, with thanks for one of the most beautiful evenings we have ever spent in the theater. It was July of 1993, and I was not scheduled to write at Wimbledon that day, so I started to duck out of the press tribune around 5, only to hear the cutting tones of my beloved colleague, Robin Finn, alerting the entire press crew: “So, Giorgio, the Missus has theater tickets tonight, huh?” Well, yes. Marianne had picked up tickets for the Stoppard play at the National Theatre on the South Bank, our favorite place in London, or maybe the world. Very often, she would see two plays in one day. This night we watched a play about a country estate in Derbyshire in 1809, where a man is tutoring his precocious charge, just entering her teens. The plot is complicated – Stoppard’s always are – but the main theme is about the maintenance of the mansion; to change or not to change? The action shifts to 1990 or so, when other humans are discussing the very same country estate. (Makes you think there just might always be an England, despite its “leaders.”) The centuries rock against each other like tectonic plates but the twains do not meet until – spoiler alert – the very last scene, when the two generations mingle on the stage. Stoppard can be highly intellectual and abstract, but suddenly my eyes were gushing, tears from nowhere. This is the best thing the theater can do – bring you to your knees, in emotion. My fine drama teachers at Hofstra taught us about “catharsis” – from the Greek, the cleansing, the purging. “Arcadia” made us think and feel deeply. In 2009, The Independent asked if Arcadia was the “greatest play of our age.” One review described “Arcadia” as “a serious comedy about science, sex and landscape gardening.” I also remember a murder mystery and physics mixed in. My best to you, sir. Perhaps you are writing? * * * More about “Arcadia:” https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-dance/features/is-tom-stoppards-arcadia-the-greatest-play-of-our-age-1688852.html https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/1993/apr/18/features.review7 https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/tom-stoppard When I was a little kid, my father used to bring home baseball record books from the newspaper office, including photos of the first class of five players elected to the Hall of Fame.

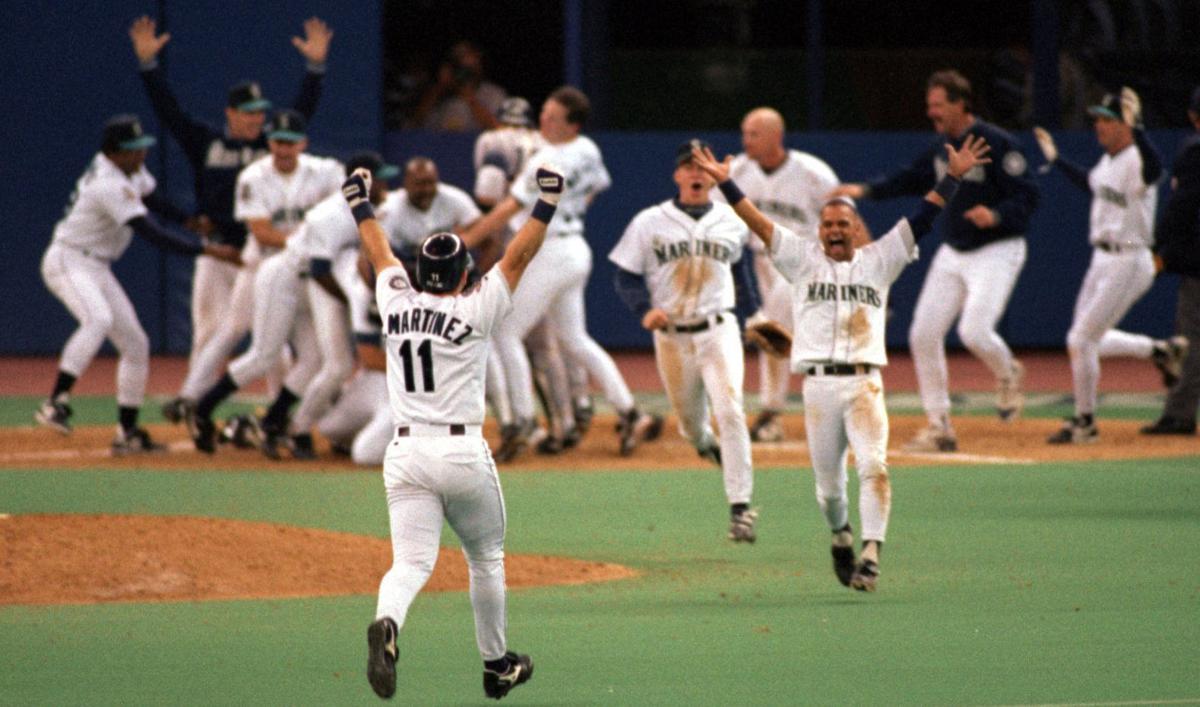

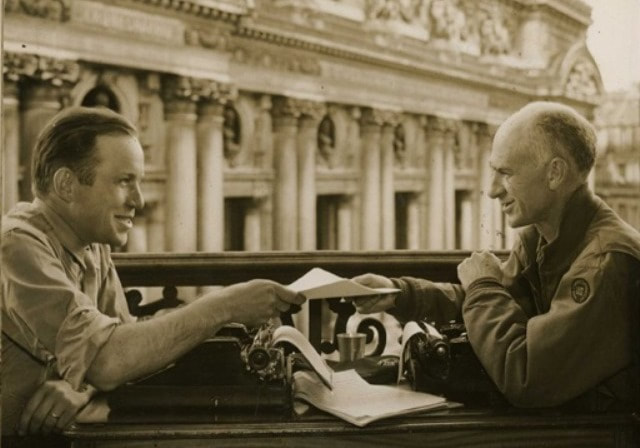

How stodgy and old-fashioned they looked in old photos – faces and bodies and uniforms that seemed clunky by “modern” standards of 1946 and 1947. Yet there they were, the first “immortals” – chosen in 1936 for the emerging Hall of Fame: Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth. I saw Cobb and Ruth at the first Old-Timers Game in Yankee Stadium at the end of 1947; Ruth was dying, in his camel’s-hair coat, his voice crackling on the primitive public-address system. He was an immortal, but he was most surely mortal. In 1947, we were also living in a time of Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial – and Jackie Robinson. More immortals. When I saw them play, did I stop to study them carefully, so I would have an engraved memory of their swing, their mannerisms? Nah. Not smart enough. We live in the moment, but I was minimally wise enough, as a young sportswriter in the ‘60s, to know I was in the presence of immortals -- Koufax and Gibson, as good as it gets; Mays and Clemente and Aaron and Frank Robinson. And when I was around the New York Yankees from 1995 to 2013, it was a privilege to watch Mariano Rivera break off that cutter that was equal-opportunity unhittable. He dominated in a modest way, no gestures, no celebrating, because, as he often says, he “respects the game.” I must add, it was also a privilege to watch Jeter and Williams and Posada and Pettitte, year after year; they soothed the ancient sting of my Yankee-tormented childhood as a Brooklyn Dodger fan. How could I hate a team that had those guys? I recently met a rabbi on Long Island who raved about a trip he had taken to Israel in the company of the evangelical Christian Mariano Rivera. I am sure Rivera’s rabbinical admirer is celebrating today, as Rivera has become the first baseball immortal to be elected unanimously. Considerating the cranks and crackpots and purists in my colleagues, this is huge. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/22/sports/baseball/mariano-rivera-hall-of-fame.html I did not have the same surety about Roy Halladay and Mike Mussina (NYT writers are not allowed to vote for awards, and I follow those rules in retirement.) The voters have confirmed Halladay and Mussina as Hall of Fame pitchers, so congratulations. And did you see Tyler Kepner’s absorbing insider explanation of what Rivera taught Halladay about the cutter? It would cost Rivera a few bucks in a clubhouse kangaroo courthouse. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/20/sports/hall-of-fame-roy-halladay.html In Rivera’s first season, 1995, I got to watch one of the best post-season series ever played, a best-of-five division thriller between the emerging Yankees and what seemed to be the emerging Seattle Mariners. The difference in that series was Edgar Martinez, a designated hitter at the peak of his game. He was unspectacular in demeanor but dominant in hitting a ball. Just before the fifth and final game, I wrote an “early” column – for the first national edition – quoting Reginald Martinez Jackson, Yankee star and by then Yankee advisor, raving about Edgar Martinez, no relation. Reggie’s raves are best read in context of my revised column, after Martinez had clubbed the Mariners into the next round: https://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/09/sports/95-playoffs-sports-of-the-times-one-martinez-is-raving-about-another-martinez.html Do I think of Edgar Martinez the way I think of Ruth, or Mays, or Koufax, or Rivera? No, but there are four or five levels of Hall of Fame players. I hate the designated-hitter rule; it has led to the current plague of launch-arc/strikeout flailers. But Edgar was not a launch-arc guy. Read how Reggie dissected his professional swings in that marvelous 1995 division series. I cannot hold being a designated hitter against Martinez; he played where they told him to play. Designated hitters gotta live, too. I remember Edgar dominating an epic series, sending Junior Griffey sliding home with a joyous cat-in-the-hat smile, (Think Buck Showalter ever wonders why the Yanks did not activate young Derek Jeter for the post-season….or why Buck did not keep young Mariano Rivera on the mound after getting two outs?) That epic coastal series was the time of Edgar Martinez, not Mariano Rivera. Now they go into the Hall together. Like Johnson, like Mathewson, like Wagner, like Cobb, like the Babe himself – by definition, tightly monitored by baseball fans and players and officials and voters: immortals, all.  Anna Duchene, Brussels, 1954. Anna Duchene, Brussels, 1954. Hal Boyle’s columns were big wherever the Associated Press was used. He was Everyman, from Kansas City, writing for Middle America, with no political bias and plenty of heart. I knew Boyle, from bowling in the Associated Press league when I was a 16-year-old copyboy. He was a jovial man whom I recall with cigar and perhaps a beer, laughing easily with everybody. He had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1945 – for his coverage of the European war -- but you would never know it. https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/harold-v-hal-boyle Now, as a recovering columnist, I am reading Hal Boyle’s columns. In 1954, he visited my Irish-born grandaunt in Brussels and wrote about the atomization of her family from World War II. (I recently came upon my mother’s cache of photos and clippings of her lost Belgian-Irish relatives.) Decades later, Hal Boyle holds up in hard-cover form; very few columnists do -- Mike Royko, Jimmy Breslin, a few story-tellers, writing about the human condition. Like the best journalists, Boyle has a fine eye for details – the bullet hole in Madame Duchene’s front doorway -- from the day a Scottish soldier she had been hiding bolted from the Gestapo, and was gunned down in the street. (He lived to old age but Madame Duchene’s daughter, Florence, and her son, Leopold, did not.) I cannot access Boyle’s column on line, but I wrote about that family in 2006: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/09/sports/soccer/09vecsey.html Boyle paints a portrait of the grandaunt I never met. On the 10th anniversary of following the Allies into Europe, he spent a few hours at her home – get this -- 7, rue Sans-Souci. (Street Without Care) Again, like the best journalists, Boyle is there to observe, to ask questions. His compassion for the old lady with her memories and her medals, surely has roots in his mother’s childhood in poverty-ridden Ireland. I never finished his collection – the aptly-named “Help, Help! Another Day!” – from a poem by Emily Dickinson – but now I am enjoying his changes of pace: communing with the graves of men who died on the Normandy killing beach, or staying in a camp deep in the Catskills, listening to the sounds of night. Perhaps his most poignant column came from defying the third or fourth rule of journalism – never succumb to the cheap device of quoting taxi drivers. But Boyle happened to ride in the cab of a philosopher who was mourning a beloved wife who had died years earlier. The man advised Boyle to cherish his own wife, and life itself, and Boyle was wise and talented enough to make a column out of his encounter. (Boyle’s own wife would die young, and he would follow, from a heart attack, at only 63.) Many great journalists are full of themselves, to the point of grimness, but Boyle was jolly, in a melancholy Irish way. He was as much at home in the camaraderie of a beer frame as he had been with the sights and sounds of combat. One thing I just learned from skimming his columns: his own meter was always running. I am convinced: what I am about to tell you is no coincidence: At that bowling alley – Beacon Lanes, 76th and Amsterdam, second floor – the coat-check was run by a highly loquacious and secure black man, who seemed to have the word “autodidact” glowing proudly like theater lights on his forehead. The man liked to chat about the books and poems he had read – most notably “Thanatopsis,” by William Cullen Bryant, using the Greek word for “consideration of death.” At 16, I looked forward to my weekly chat with the brother. Now, 63 years later, I pick up Hal Boyle’s collection. His latest column is from Jan. 9, 1964, called “Nostalgia Is a Medicine to Cure the Blues,” with one-line observations about things you don’t see much anymore. One of them was: “Anybody with a claim to culture could prove it by reciting aloud the concluding lines of William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis.” This means, to me, without a doubt, that Hal Boyle, Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist of the Associated Press, had been chatting with the same vibrant coat-check man at the Beacon Lanes in the season of 1955-56. With that discovery, I feel a great kinship with the man who visited my grandaunt in war-ravaged Brussels. I wish I had read more of Hal Boyle, had asked more questions, back in the day. But I did bowl with him. In the final hours of an ugly year, I stuck with the tried and true.

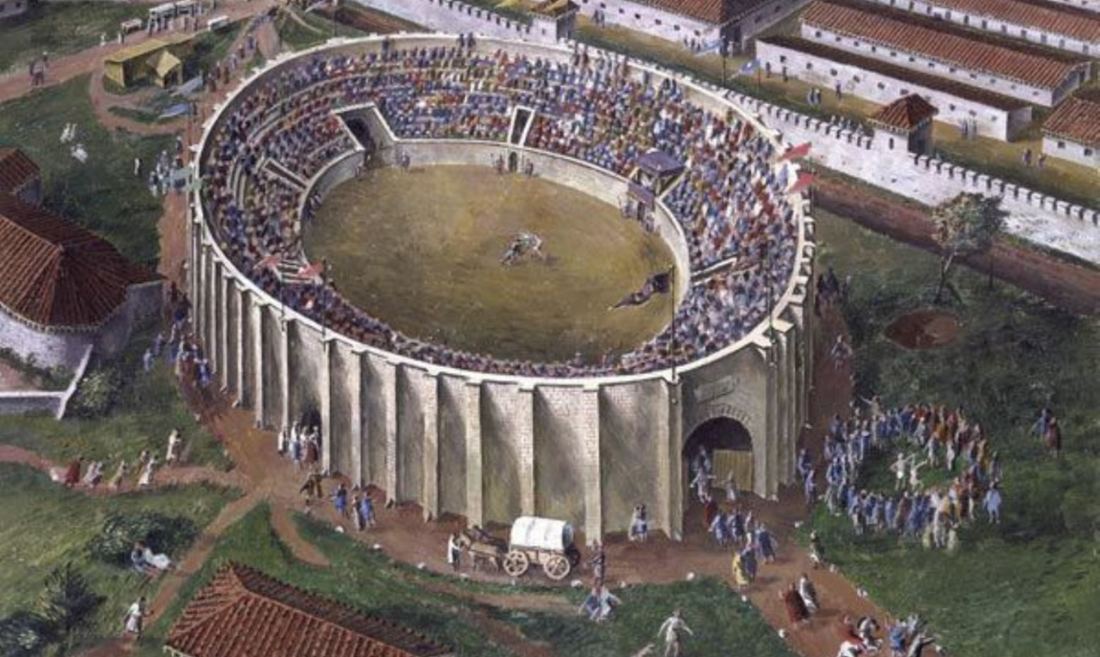

Our local classical station, WQXR-FM, was playing the top 100, as chosen by listeners. It was reassuring to hear music that stirred people and soothed people in other dark times, with other crackpots and despots flailing around, and the music survived. Then again, we have seen votes go wacko in a democracy. When the Gilbert and Sullivan spectacle, “Pirates of Penzance,” popped up in 10th place, my reaction was, “Wait, WTF, how did that get in there?” The WQXR–FM web site had the same reaction: Was it was the work of Gilbert and Sullivan superfan sleeper agents? Or is everyone just really excited about the end-of-year New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players production of Pirates at the Kaye Playhouse. (It turns out that it very well might be both, as the New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players staged a campaign to launch the opera into the countdown — and it clearly worked. Trolls. Bots. Hacking. Malware. Whatever they are. Sounds like a job for Super-Mueller, but Our Civic Protector is said to be otherwise occupied with his investigation into more serious shenanigans. Other than the jolt of Gilbert and Sullivan coming in 10th in any classical music ranking, it was a joy to hear oldies soothe the dark days and nights as 2018 slunk off into history. Beethoven had four symphonies in the top 10, including his Ninth, with the rousing “Ode to Joy,” now becoming a staple ‘round midnight on Dec. 31. Some of the most familiar music can be considered chestnuts, but I was happy to hear them, knowing that new and adventuresome and inventive music will be presented by John Schaefer on “New Sounds” and by Terrance McKnight on his weeknight show. Plus, as 2018 ebbed, I heard some of my favorites, Dvorak and Copland and Vaughn Williams and Smetana and Bartok and Barber and Ravel and Satie and Lenny Himself, conducting his “West Side Story: Symphonic Dances,” which always makes me feel 16 again, walking the streets of my home town, feeling, “could be, who knows?” In the symphonic version, I could hear the lyrics of Stephen Sondheim: Could it be? Yes, it could Something's coming, something good If I can wait Something's coming, I don't know what it is But it is gonna be great. Happy New Year. I had forgotten that I once scored on a header in the ancient amphitheater at Caerleon, Wales.

I was reminded of my stirring athletic feat – sending the ball spinning into the corner of an admittedly spectral goal – when I recently read a terrific book: “The Edge of the Empire: A Journey to Britannia; From the Heart of Rome to Hadrian’s Wall,” by Bronwen Riley. I read about the book in a review in the Times by Jan Morris, which was good enough for me. People don’t know enough about the Roman Empire. Or, rather, I don’t. I’ve encountered Roman ruins in Ephesus, Turkey, and southern France and silver mines in Wales, and I speak just enough French, Spanish and Italian to realize the debt to Mother Latin. But somehow I got through college without ever taking a course in the Roman Empire. Quid pudor est (What a shame, courtesy of Google Translate) So, about the header. My epic goal took place while we were touring Wales, oh, a few decades ago, with our former Long Island neighbor, Alastair, who had retired to his home in Wales, with a view of the Brecon Beacons, the hills to the south. Alastair had a Scottish surname but was a true Welsh patriot who loved driving us around to chorus recitals and old ruins and vacated railroad lines from his youth. (Whenever Alastair crossed the Severn River bridge from England back home to Wales, he would mutter something about “them” – the country in the rear-view mirror.) On this lovely summer day, Alastair drove south from Brecon, telling us about the great rugby teams of his youth in these old coal-valley towns. We reached flatter ground where the Usk River widened, and Alastair found the old Roman amphitheater, now just vestigial green mounds and a few outcroppings of stone, surrounding a lush green lawn. In Roman times, the outpost was known as Isca Augusta. Riley’s book taught me that the Roman amphitheaters all over the empire conformed to style: outbuildings for entertaining Roman dignitaries on inspection tours. I did not know that the same spectacles in Rome were repeated in the colonies – animals fighting animals, gladiators fighting animals, gladiators fighting gladiators. This primal gory spectacle was the National Football League of its time. The old arena was empty, as far as I could see, as we entered through one of the passageways. The ground underneath felt firm. Once we were inside, the grassy mounds surrounding the arena were higher than my head. I felt as if I were in Wembley or Olimpico or Bernabeu, some of the modern stadiums in outposts of the Roman Empire. Still fit, in my 40s or 50s, I felt the urge to jog…to open it up, to let it go. Down at the other end, I imagined a rectangular goal and some pigeon of a keeper, just ripe to be juked out of position. Just like CR7 or Ibra these days, I closed in, leaped in the air and connected with a gorgeous service from my wing, and I flicked the ball into the nets, as thousands roared. Well, not thousands. Nobody cheered. Right about then, I noticed a little knot of children with an escort, in one of the runways, against the rocky sideline, staring at this daft old bloke. I decided not to tear off my shirt to celebrate – bad form with a dozen tykes staring at me. That was my goal. We continued our drive through Alastair’s homeland. A few years later, he inconsiderately dropped dead while shopping for food for his border collie, which put an end to our annual post-Wimbledon visits to idyllic Welsh summer – flower-festooned pubs (with good food!) alongside the Usk canal, plus his occasional glider sorties from the nearby Black Mountains. Wales all came roaring back to me after the Times book review for Bronwen Riley’s book. She describes how Julius Severus, the newly-appointed governor of Britannia, traveled the 1486.9 miles from the bustling Rome docks in the year 130 to supervise the building of Hadrian’s Wall. (One thing I learned was that the famed Roman galleys did not, repeat not, rely on slave labor, but instead were powered by well-trained military men, many earning their citizenship through 20 years of expert labor.) The book describes the over-land portion of the journey in Britannia, stopping briefly at the growing town of Londinium (London) and then heading west to Isca Augusta (Caerleon), and then north to Deva (Chester) and on to the growing wall. That is right: Hadrian managed to get his wall built, thereby separating neighbors and relatives, brutally and cruelly. Omnia mutantur magis ... (The more things change… in Latin.) Those Roman emperors could really build things, back in the day. They built an arena in Isca Augusta that I visited one green summer day, thinking not of Romans but of a dashing header, smack, into a make-believe net. * * * Jan Morris’s recent review in the NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/22/books/review/the-edge-of-the-empire-by-bronwen-riley.html When friends in Jerusalem and the Upper West Side send the same link, it makes sense to read it -- and pass it on. Roger Angell, 98, has some thoughts on election day and citizenship.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/get-up-and-go What could be more American than an essay on voting by a hallowed member of the writers' wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame? Enjoy....and vote. http://www.joedarrow.com/sports-figures/ (The art was a bonus. I found it on line, and consider my posting it here as an endorsement for any artist who can put these three dudes in the same work.) The following is a contemporary version of the classic warning of the Holocaust, by the Rev. Martin Niemoeller. This was written by my friend, Arthur Dobrin, the Leader Emeritus, Ethical Humanist Society of Long Island, and professor emeritus, Hofstra University.)

First they mocked the handicapped and then they boasted about assaulting women. And I did nothing. Then they called black people stupid and Muslims terrorists. And I did nothing. Then they called Mexicans rapists and the press the enemy of the people. And I did nothing. Then they called political opponents traitors and those who body-slam critics “my kind of people.” And I did nothing. Then they posted pictures of dollar bills over Stars of David and said transgendered people couldn’t serve in the military any longer. And I did nothing. Then two African Americans were shot dead in a supermarket, pipe bombs were sent to critics of the administration and eleven Jews were murdered in a synagogue. And now the president laments the hate in the country and then tweets about baseball. * * * (The incident in the video has played out dozens of times, and the message continues: take matters into your own hands. Trump’s behavior, as he foists himself upon a grieving Pittsburgh, reminds me of George Orwell’s immortal warning in the novel, “1984:” If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face, forever. Trump’s impact on the U.S.A. and the world is more and more apparent. Nearly half this country voted for this man. At the same time, the pastor’s daughter, Angela Kasner Merkel, has announced she will leave the chancellor’s post of Germany in 2021. She witnessed two totalitarian regimes – Nazi and Communist – and became a beacon of humanity in a world growing darker by the day. My thanks to Arthur Dobrin. Barack Obama Gave a Speech on Television.

I had tears in my eyes. I was sad for what we have surely lost – an intelligent, verbal president who speaks of values. When the former president mentioned Michelle Obama and their daughters, I felt empty, as if thinking of good neighbors who have moved away. He delivered a civics lesson at the University of Illinois, urging young people to vote -- clearly political but so rational and timely that it rose above partisanship, to become a warning: Where have we gone? What have we done to ourselves? He cited the white-power people who stomped in psychic jackboots through Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, in plain daylight, not even bothering with hoods. He evoked the man who is still president as of this writing, who claimed there were good people on both sides. Barack Obama asked, plaintively: “How hard can that be? Saying that Nazis are bad?” My wife said that should be a bumper sticker. A president who can write and read and speak his native language. Imagine. On Friday in Illinois, he was at his best in the national and global bear pit -- Laurence Olivier performing Shakespeare’s speech for Mark Antony in “Julius Caesar:” “So are they all, all honorable men.” The previous president spoke against stereotyping people, saying he knew plenty of whites who care about blacks being treated unfairly, saying he knew plenty of black people who care deeply about rural whites. Then he added: “I know there are evangelicals who are deeply committed to doing something about climate change. I’ve seen them do the work. I know there are conservatives who think there’s nothing compassionate about separating immigrant children from their mothers. I know there are Republicans who believe government should only perform a few minimal functions but that one of those functions should be making sure nearly 3,000 Americans don’t die in a hurricane and its aftermath.” Like Shakespeare, he was making a bigger point: there is a malaise loose in the land. At one point he said Donald Trump is “a symptom” and not “the cause.” In other words, Trump is an illness that has been coming on for years. I nodded grimly, in my den, thinking of the McConnells and Ryans, who have sat by maliciously, allowing a Shakespearean character, the worst of the buffoons, the worst of the tyrants, to tear things apart. Was I imagining, the other day, that these politicians were squirming in their seats in the cathedral, along with their fidgety wives, listening to the orations for John McCain, wondering if anybody would ever confuse them with patriots? On Friday, Barack Obama gave notice to the young people of many shades and facial characteristics in his audience: you are the largest population bulge in this country, but in 2016, only one in five of you voted. “One in five,” the playwright emoted, enunciating his own words. “Not two in five or three. One in five. Is it any wonder this Congress doesn’t reflect your values and your priorities? Are you surprised by that? This whole project of self-government only works if everybody’s doing their part.” The television showed the college students nodding, or averting their eyes. Will they remember this warning at mid-term elections in early November? So many distractions these days. So easy to get lost, twiddling thumbs in the social media. Shakespeare was borrowing stories from earlier centuries but Barack Obama has been active in public life. On Friday he returned to the stage to deliver artful words, dramatically delivered, surely from the heart. How many reminders, how many chances, do we get? *** The transcript of Barack Obama’s speech (really worth reading): https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/9/7/17832024/obama-speech-trump-illinois-transcript I’ve been reading a lot of books lately.

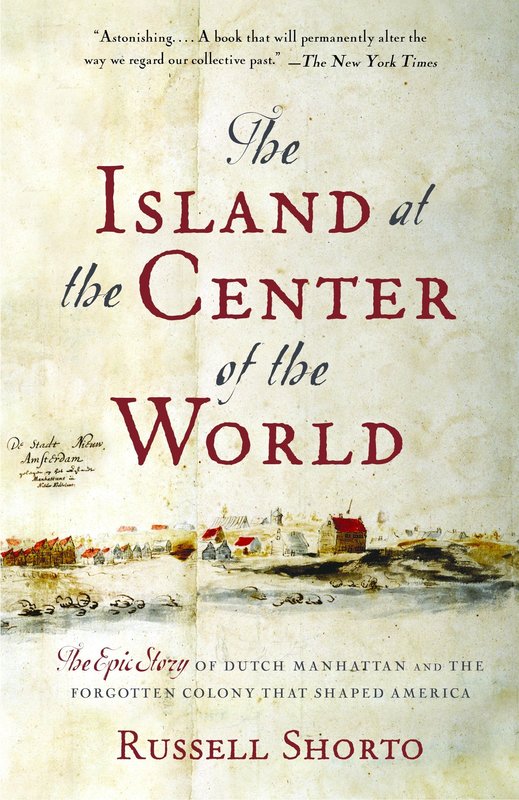

I think I know why. My latest has been a gripping history of the first settler to advocate local government and polyglot culture among people he labelled “Americans” -- a new concept in the mid-17th Century. Adriaen van der Donck was perhaps the first “New Yorker” – except that it was still named New Amsterdam in his time. Of course, my discovery is a trifle late. The book, “The Island at the Center of the World,” by Russell Shorto, was first published in 2004. I don’t know how I missed it, until our friends Ina and Maury gave us a copy recently. New Yorkers know the names of Peter Minuit and Peter Stuyvesant, executives sent to the New World to regulate commerce for the Dutch West India Company. Van der Donck, trained in the law, was also sent to New Amsterdam to help the company make more money, but he saw the mélange of Dutch and England, French and Spanish, Africans and Native Americans, and he realized they constituted something far more than company workers. Van der Donck was sent as a lawman to another Dutch region, Fort Orange, now Albany, where he learned Indian languages and encouraged trade and visited their villages. Native Americans were somewhat free to bargain, to visit, to argue and even sue. Why don’t we know more about him, and more about the contribution of Dutch society? For that matter, why don’t we know about the petition signed on Dec. 27, 1657, by 31 English settlers, protesting the persecution of Quakers. (Not one signee was Quaker.) And, while they were speaking up for Quakers, the English protesters proclaimed: “The law of love, peace and liberty in the states extending to Jews, Turks and Egyptians, as they are considered sonnes of Adam, which is the glory of the outward state of Holland, soe (sow? GV) love, peace and liberty, extending to all in Christ Jesus, condemns hatred, war and bondage.” The petition was signed in the Long Island village of Vlissinge, today known as Flushing, the home of the Amazing Mets and a bustling Chinatown and the start of a thriving Korean diaspora moving eastward along Northern Blvd. (the roadway of Tom and Daisy Buchanan.) The Flushing Remonstrance – issued at the end of the time of Adriaen van der Donck -- is one of the great statements in the history of North America. It has rarely been more relevant than now, when “sonnes of Adam” are being separated psychologically, as children are grasped from their parents by agents of an increasingly cruel state. In a way, the current regime led me to read this book about Dutch settlers. The puffy, petulant face of a child tyrant -- as well as his dissonant voice, the President as shrill earworm -- have driven me from the news channels (and the repetitiveness of most commentators, and the commercials for old-age “remedies.”) Lately, I have taken to sitting near the evening music on WQXR-FM and reading books. My wife, as part of her family genealogy studies, just finished “Domesday: a Search for the Roots of England,” issued by Michael Wood in 1986, and also a classic television documentary. One more point about books: one of the heroes of Russell Shorto’s book is Charles Gehring, an American scholar, who has spent much of his career on an un-numbered floor in a state building in Albany, translating historic Dutch handwritten documents into contemporary English. This book adds to my immense respect for scholars like Gehring – and Shorto – and Wood. They help us see ugly times in the 21st Century, in perspective. * * * The Flushing Remonstrance: https://www.nyym.org/flushing/remons.html |

Categories

All

|