|

I am so thrilled that the New York Times obituary editors ran a lovely obituary of Joe Christopher, a member of the early New York Mets – and my friend over the decades.

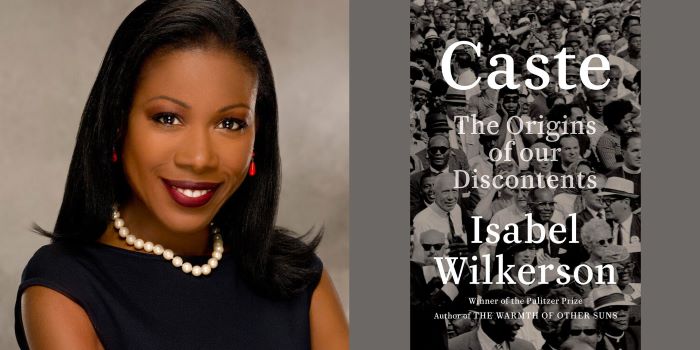

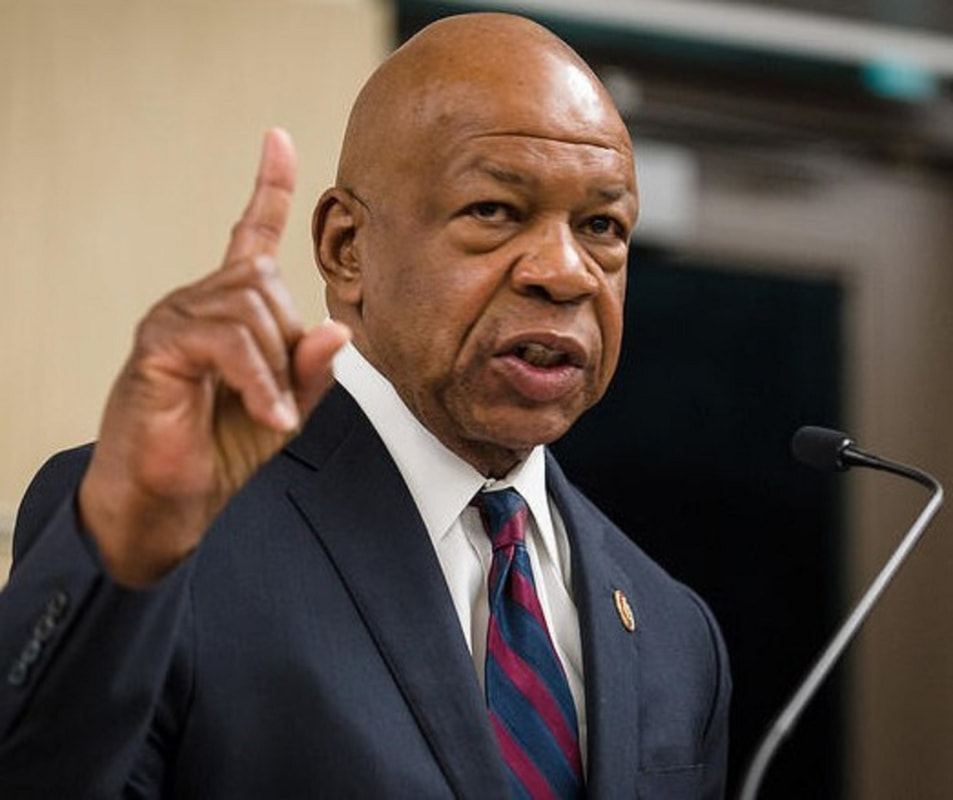

Joe touched a chord in me because he was mysterious and deep. I have learned more since he passed last week, from his daughter Kameahle Christopher. I also collected memories of Joe from two of his old teammates. In case you miss the NYT obit, here it is (for those who can access it). It is written by Richard Sandomir, now an obit writer, but previously a star sports-media critic (back when the NYT had a sports section.) https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/05/sports/baseball/joe-christopher-dead.html I became intrigued by Joe Christopher in the first year of the Mets when he was a backup outfielder. Joe was from St. Croix, apparently the first player born in the Virgin Islands to play in the major leagues. He was a mix of cultures and languages, introverted, but also comfortable chatting with some of the young Chipmunk writers covering the club. “I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am,” he would say, softly. Sometimes he would chat with me about mysterious religious trends. I don’t claim I understood, but I think he sensed he had a friend. He was up and he was down with the Mets but in 1964 he played regularly and batted .300. (The obit tells how in the final game he dropped a bunt single in front of old Ken Boyer of the Cardinals to pretty much clinch the distinction of being a .300 hitter. In the pressbox in St. Louis, I almost cheered out loud.) His career sputtered again in 1965 and he was soon gone from the majors. Recently, two former teammates had nice things to say about Joe: Larry Elliott, a fellow outfielder in 1965, sent this memory: “I was trying to break up a double play against Philly. I did not get down in time and Ruben Amaro hit me in the back of my head with a throw. It was my fault. I was in the hospital for five days and Joe was the only one to come and visit me." My e-pal, Bill Wakefield, sent his memory of 1964, when he was a rookie out of Stanford and reported to the Mets’ spring hotel in St. Petersburg, Fla. “The front desk says, yes, we will give you a room, and assign your roommate. So I take my suitcase to the room. Open the door, and inside is a startled Joe Christopher. I said, ‘I’m Bill Wakefield and I’m your roommate.’ He seemed surprised but said, fine” (Wakefield doesn’t need to note that Blacks and whites were not rooming together in those days. And Christopher, who had been introduced to segregation in the U.S., was surely aware of that.) Shortly, Wakefield received a call from Lou Niss, chain-smoking, worry-wart travel secretary of the Mets “Come to come to the lobby immediately. I assume it's to get instructions -- don't drink in the hotel bar -- that's Casey's spot -- don't be late for the bus -- wear shower shoes on the bus not spikes, etc. “He says – ‘ Bill we are moving you in with Larry Elliott -- make the change immediately.’ And sort of as an afterthought, he said -- I paraphrase – ‘Baseball has made progress but we are not ready for black and white roommates yet." “I have no idea -- I just want to do all the right things. So I go back down to the room -- Joe is still there -- he kind of smiles at me -- and I said Lou Niss has assigned me a different room. “I always worried that Joe thought I had complained and that was the reason for the switch. I really didn't care. "So I packed up and moved to Larry's room.Joe never mentioned it again. He and I became pretty good friends. “Joe and I laughed about it over the course of the season. He even got a big smile on his face and would say ‘Nice going, Roomie!!!’ Great guy.” I have one more memory of Joe, who could wiggle his ears with the best of them. A knot of Mets writers were taking the sun behind the Mets’ dugout during a game in Chicago in May of 1964. As the Mets frolicked to an unforgettable 19-1 final score, Joe would trot in from right field after each inning, levitating his cap with his ears – just for the writers’ sake.” Joe’s major-league career fizzled but we kept running into each other. In the late 60s, I was in Puerto Rico writing for Sport Magazine about Frank Robinson managing a team in the winter league. I was at a game in Caguas when I spotted Joe playing for Santurce…and we agreed he would ride back in my rental. Then he won the game with a grand-slam homer in the ninth inning and the fans were so annoyed that they made motions to tip my car over. We laughed about it all the way back to Santurce. I always reminded him how he almost got me killed. Joe and I ran into each other in the 1980s near Times Square. He was carrying a large rectangular portfolio used by artists to protect their work. He came up to the Times for a while, but I never saw his work -- part of the mystery of Joe. The other day, I chatted with Kameahle Christopher, a paralegal with Amtrak, who lives outside Baltimore, and asked about her dad’s inner life. “He was interested in pre-Colombian art,” she said. “He was in touch with the ancients, the Olmecs and Mayans. He was into numerology…would ask your birthday, would predict things,” Kameahle said. “He was gifted spiritually.” I asked her about her dad’s childhood and she said he was raised in Oxford, a small settlement in St. Croix. “He grew up in a small house in the mountains,” she said. “He walked everywhere, and when he came home at night, he learned to follow the North Star. He said, “‘I’m not going to grow up like this.’ Nobody had ever left the islands. He endured hardships, but he used to tell himself, ‘I’m Joe from Oxford…and if I have to walk, I’ll walk.” In his later years, Joe wanted a job teaching baseball; “he carried his baseball gear in his car,” Kameahle said. Joe would coach somebody for the joy of it, remembering how much he had learned from coaches like Rogers Hornsby, Sheriff Robinson, Paul Waner – and his driven roommate with the Pirates, Roberto Clemente. After talking with Kameahle Christopher, I felt I knew her dad better – where his inner strength came from, standing in the clubhouse, a marginal Met, telling young writers from New York: “I’m a better ball player than you guys think I am." Kameahle’s loving portrayal made me miss him even more. ## Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize when she worked for The New York Times. Later, she wrote a best-selling book about the great northward migration of Black Americans. In the process, Wilkerson earned a ton of airline miles, allowing her to fly first class much of the time. In addition to the few extra inches of space, Wilkerson was able to do research for her new book -- on the caste system in the United States. Even when she presented her boarding pass for Seat 3A, she was still treated as a stranger, a lower caste, as a female and as an African-American. Confused flight attendants stared at her and suggested she just keep walking to the back of the bus. Wilkerson also had to endure jostling for overhead-rack space from white male passengers. Anybody who is Black, or has friends and relatives of color, knows the drill. A few days after the 2016 election, Wilkerson settled into her first-class seat and noticed “two middle-aged white men with receding hairlines and reading glasses” who quickly bonded, with one stranger telling the other: “Last eight years! Worst thing that ever happened! I’m so glad it’s over!” The two instant buddies then celebrated from Atlanta to Chicago, assuming that the new President would be "good for businss." I am 100 percent positive that Trump's appeal to money guys helped advance the racism loose in the country. . Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” came out in mid-2020, before the little lovefest of assorted cut-throats and sociopaths and bigots and other Trumpites at the Capitol. I just caught up with “Caste” and found it compelling, as Wilkerson compares America’s enduring racial prejudice with the age-old caste system in India as well as the caste system that killed at least 6 million Jews and others regarded as untermenschen in Nazi Germany. Wilkerson points out how Hitler studied how whites in America marginalized and terrorized Blacks long after the so-called Civil War. Wilkerson also points out that contemporary Germany does not display statues and markers of the Hitler days, whereas the U.S. is only now coming to grips with Black youngsters having to attend schools named after Robert E. Lee, that old secessionist-slavemaster. It never went away. Wilkerson also presents dozens of examples of lynching and mutilation of Blacks, under slavery and long into the 20th Century, and still going strong in spirit. Trying to understand the American system in terms of the Indian caste system, Wilkerson flew overnight from the U.S. to London to attend an academic conference on caste, attended mostly by people of Indian ancestry, whether English or Indian or other nationalities. She immediately realized that the elite castes – even among academics -- were identifiable by lighter (Aryan) skin as well as a deep aura of entitlement, whereas members of the Dalit (Untouchable) caste – even with doctorates and other professional titles - - were of darker skin and reserved demeanor. She became friendly with a highly educated Dalit at the conference who described how his sister had cried about her dark skin when it was time to seek a husband. From her new friend, Wilkerson learned about Bhimrao Ambedkar, who renounced his Hindu standing and became a leader of the Dalits in the time of Gandhi. Her education about India will surely be the reader's education. As I read Wilkerson’s book, I thought about the new demographics in the U.S., as it heads toward a “minority” majority in the next decade or two. The white terrorists who stormed the Capitol in January are quite likely feeling marginalized by the talented and poised people of color who have become more evident in recent years. Some kind of change was gonna come -- or so some of us thought. It's been in the public consciousness for decades -- with the great Sidney Poitier embodying a possible new era in the 1967 movie ”In the Heat of the Night." For other examples, Wilkerson mentions the intelligent and handsome and poised couple that lived in the White House from 2009 to 2017, plus examples of changing America all over public life. As the pandemic endures, I gain information on the evening news from professionals like Dr. Kavita Patel of Washington, D.C., Dr. Vin Gupta of Seattle, Dr. Lipi Roy of New York and Dr. Nahid Bhadalia, with their kind and patient faces, with their knowledge and passion. The international look of today’s medical experts reminds me of that very good movie, “Gran Torino,” when Clint Eastwood, an auto worker with dark secrets from his military service in Korea, meets his new physician. (I'll never forgive Eastwood for his ugly televised rejection of Barack Obama, but his movie shows the growth of an aging bigot in a changing Detroit.) Last week, on MSNBC, Lawrence O’Donnell presented the viral immunologist who helped develop the Moderna vaccine -- -- Kizzmekia Shanta Corbett, Ph. D., who turns 36 on Jan. 26. Dr. Corbett saw the code for this new virus as it popped in from China, early in 2020, and linked it, in her mind, with anti-virus codes available here -- “over a weekend,” apparently. The rapport was clear between Dr. Corbett and O’Donnell, who is proud of being of Irish descent in Boston, and is one of the most open champions of African-Americans in public life. However, at the same time, a huge swath of white Americans is acting out in public, scorning vaccinations and masks, storming the Capitol a year ago, yelling racial insults at police while trying to brain them with heavy weapons. Many white Americans grew up thinking they had an edge over anybody with darker skin. Isabel Wilkerson’s powerful book points out the growing strains on the old American caste system. * * * Dwight Garner, one of my favorite writers at the NYT, reviewed “Caste" in July of 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/31/books/review-caste-isabel-wilkerson-origins-of-our-discontents.html Lawrence O'Donnell's interview with Dr. Corbett -- real life, not a movie:  Diwali, Trafalgar Square, 2020 Diwali, Trafalgar Square, 2020 When Kim Ng, of Chinese descent, was appointed general manager of the Miami Marlins on Friday, she became the first female to hold that role in top American sports. Americans like to congratulate ourselves on being the land of opportunity, which it has been, although under duress from our child-kidnapper-in-chief in the past four nasty years. When voters elected Kamala Harris, part Jamaican, part Indian, and female, as the vice president nearly two weeks ago, this was cause for celebration in the U.S. -- although not by militia-type worthies with rifles on their hips who came out of the woods to help "supervise" the polling. As for the rifles -- only in America. Oddly enough, this opportunity stuff goes on in other countries, too. Currently in London, under the leadership of Mayor Sadiq Khan, of Pakistani ancestry, large-scale celebrations of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, are being held in public places. This is not new. Two decades ago, my wife and I were in London (for a Giants football game!) when we ran into a modest Diwali celebration, some music, some dancing -- and we saw four female police officers, in classic bobby uniform, dancing along with the celebrants. Only in London. Canada has its own share of vibrant minorities. I was reminded of this in the Saturday NYT in a touching profile of an orphan, from India, who lobbied his way to adoption in Toronto and now runs a high-end restaurant there. When he was 8, Sashi was a street kid, abandoned, taken into a home in Tamil Nadu, operated by a small Canadian outfit, Families for Children. There are places like that all over India. My wife, Marianne, used to escort children from Pune to the U.S. for pre-arranged meetings with their adoptive families. ("I am the stork," was her motto. I think her total of kids was 24.) The U.S. was not the only country involved in adoptions. Canada was, and Norway had a large presence in India. Children in these orphanages know what is going on: they are on display. They are not shy about asking foreign visitors: "Take me with you." (My wife still talks about the sadness of a girl, heading to her teen years, who had realized she was not being adopted.) But as Catherine Porter writes in her poignant story in the NYT, young Sashi, with the desperation of a survivor, spotted Sandra Simpson of Canada, a return visitor to the orphanage, and he persuaded her to take him to Toronto and adopt him into her large brood. How Sash Simpson became a top chef, four decades later, is a tribute to his drive to get in the back door of a restaurant, and do any job, and keep learning. He made his own luck, with the help of the Simpson pipeline, and others. His restaurant -- Sash -- is hurting during the pandemic, but he gives the impression that he forced his way this far, and will survive. Only in Canada. Then there is Ireland, where Hazel Chu, of Chinese heritage, has become mayor of Dublin, replacing Leo Varadkar, of Indian heritage, the first gay mayor of Dublin. With my Irish passport (courtesy of my grandmother), may I say: "Only in Ireland." What a waste. Nearly four years, over 235,000 lives, untold damage to the environment, friends betrayed, alliances broken. What a waste. But now we have a chance to start over, and I want to credit one source for the grace and vision and strength behind this chance to recover -- the Black public figures who made such a big difference. In the same year that a white police officer openly ground a Black man’s life into the pavement, the best and brightest helped elect a centrist who might, just might, pull some disparate parts together again. The tone of this election year was set by Blacks who have been preparing for years, for decades, for centuries, for this moment. One great part was former President Obama sinking a feathery impromptu shot as he strolled through a gym – one and done – and as he kept moving he said, over his shoulder, “That’s what I do” -- Just as when he sang “Amazing Grace” in a church honoring slain members. The tone of this election year was set early by Sen. Kamala Harris who began a primary debate by reciting racial injustices to one of her competitors, former Vice President Joe Biden. He blinked and took it, seemed to be listening, and months later he had the grace to select this accomplished lawyer/prosecutor/campaigner as his running partner. Grace under pressure, by both. * * * Now I want to praise four others who raised the grace level in this country: Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland passed last year, after setting a high level of righteousness in Congress. I witnessed him leading some sports/drugs hearings years ago, and ever since I have referred to him as The Prophet. In his final months, he admonished balky witnesses, “We’re better than this.”

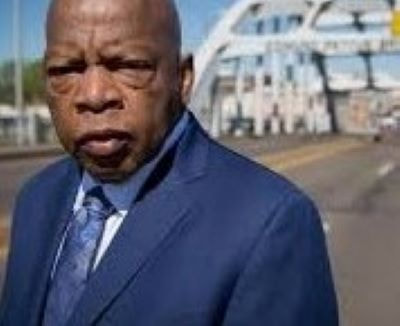

Rep. John Lewis also did not make it to this election, but he had been setting an example since the police beat on him back in the ‘60s, at lunch counters and on the Pettus Bridge. He survived that, served in Congress, seeming so innocent but actually a living holy man, tempered in the flame. Stacey Abrams lost a narrow race for governor in 2018, and soon used her intelligent smile, her knowledge, her persuasiveness, to help register voters – Black voters – in the South, where the desire to vote means standing on line in heat or rain for many hours, by Republican plan. This week, Abrams’ work helped throw two Senate races in Georgia into runoffs, early in January. Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina changed history by endorsing Joe Biden, who had just gone through two disastrous primaries in the frozen North. Clyburn is one of the most composed of politicians, no bluster, no swagger, just serene confidence. He read the mood of South Carolina perfectly, and gave the nation a Democratic candidate who could balance the disturbed posturing and fatal incompetence of Donald Trump. * * * The positive effect on this nation will carry over into the new year, the new regime. Trumpites gloried in their man depicting Philadelphia, any urban setting, as dangerous, but a white President and a Vice President who is part Jamaican and part Indian live up to the professed ideals of this country. As it happens, my family has some Jamaican and some Indian ancestry, as well as Black American, and Latino, and Asian, all kinds of Europeans, including the lady I live with who can trace herself to William the Conqueror and early New England settlers. One young man in the family – with some Black ancestry -- called his grandmother in a nearby Atlanta suburb on Saturday to deliver the news that Biden had won. * * * And Saturday evening, a joyous, liberated, masked, socially-distanced, horn-honking, all-colors-of-the rainbow-crowd in a parking lot in Delaware greeted the new look of the Biden and Harris camps -- people who seemed to like each other, and love their children and speak comfortably of making this country work for everybody. The mixed racial makeup in that crowd seemed to match the impromptu crowd in the streets of Minneapolis when George Floyd was murdered, only this time not to protest but to cheer, to smile, to breathe, Maybe, just maybe, things get better. “I suspect that seeing NYC burn arouses strong feelings in you,” writes a friend from Queens, long living overseas.

* * * We sat in our den with a visitor from Moscow and watched smoke pour out of the Parliament building. This was October of 1993; our friend was frightened because her son was a journalism student in Moscow and she knew he would get up close, to observe, to report, maybe to protest. Now it is our turn. My wife and I sit in the same den and watch our country – places we have lived and visited – quiver with rage. One over-reaction and we could have Moscow-on-the-Hudson, Tienanmen-Square revisited. I feel the way our friend must have felt that warm autumn day when she watched smoke rise above the Moskva River. New York is my hometown and it’s in my blood, ever since my father took me around, teaching me names and histories. I still see New York through the prism of being 5 years old and watching Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an old white wizened president, campaign through Queens in an open limo during a cold drizzle, or being 7 and having my father call from the office and say our team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, had just signed Jackie Robinson. I see New York from memories of gentle folk, bootstrappers from Queens, who met sometimes in my family living room, in a discussion group strictly maintained at a 50-50 black-white ratio. So many white people have lived more comfortable lives because of the enslavement of so many black people. We can’t get past it. It would be interesting if we could go back in time with those nice people, long gone, and in 2020 terms discuss America’s Original Sin. Now, from my safe perch in a nearby suburb, I feel viscerally sick when I see video or photos of broken windows, burning cars, confrontations. People are expressing their horror at the murder, caught on a smartphone camera, of George Floyd by four police officers in Minneapolis. I feel proud of the Americans who have flocked, mostly in peace, to express their believe that Black Lives Matter. The Floyd family has cited religion to score violence and revenge, but this is not a cool time, and I know there are bad actors, white and black, who want to cause anarchy and fear. The rock-throwers and the window-breakers will give racists a chance to break heads in the name of law and order. (Tom Cotton, you old op-ed sage, I’m talking about you.) I’ve been lucky to travel all over the States -- Minneapolis-St. Paul, Atlanta, Seattle, LA, Chicago. For two years in the early 70s, we lived, on assignment for the Times, in Louisville, Ky., -- five homesick New Yorkers nevertheless blessed with two stimulating years. The other day, from Louisville, I saw a story that gave me hope, or rather temporary hope – a human chain of white women at the front of a protest, ahead of black protestors, sending a physical and emotional message: “We got you.” Our next-door neighbor in Louisville would be so proud of these protestors. Rabbi Martin Perley had built bonds with the African-Americans of the 60s, so that when Louisville seemed ready to go up during a protest, he joined other civic leaders in walking the city’s West End, urging people not to take out their rage on their town. So I was proud of the white women of Louisville who went up front, but then I read about the police shooting of a well-known BBQ merchant on the West End, who may have fired a pistol in response to looting outside his door. So we’re back where we started with George Floyd. Now it is our turn in the TV den to watch nightly confrontations in New York. I spy a street or building or bridge and know exactly where it is. I have walked there and chatted with fellow New Yorkers; I have ridden the buses and subways; I drive comfortably all over my hometown. In my home borough of Queens, the Cuomos lived 10 blocks to the east of my family and the Trumps lived 10 blocks to the west of our busy, noisy street. Most days, Cuomo is hectoring New Yorkers to stay smart about social distancing and keeping an eye on the bumblings of the mayor. On Friday that disturbed and dangerous president brayed that George Floyd would be so proud of the big stock-market leap. What a jackass. Trump is the Republicans’ kind of guy. We are all paying for the anarchy and hate and stupidity he has emitted. Still, I take hope when I see blacks and whites, Latinos and Asians, mostly young, demonstrating their idealism, while we sit in front of the tube, like our friend from Moscow once did. As of Monday morning, the Brett Kavanaugh hearing is still on for Thursday.

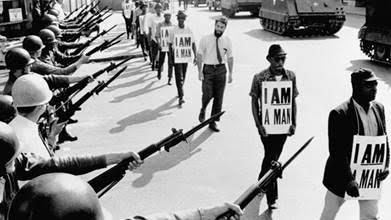

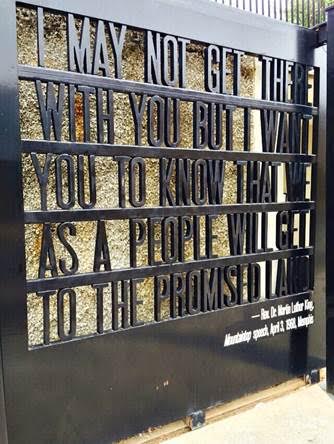

I find myself viscerally repulsed by the prospect of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford being verbally pawed over by part of the Senate committee. I recently watched a documentary of the Anita Hill questioning in 1991. Clarence Thomas was right, it was a high-tech lynching, only it was Anita Hill who was assaulted by (white) (male) senators. With deadpan zest, they made her enunciate every vulgar detail about her encounters with Thomas – her straight-laced, old-fashioned religious decency being poked and prodded. There in the clips is Joe Biden, good old Uncle Joe, (white) (male) (Democrat), blandly patronizing Anita Hill, oozing neutrality, handing off the ball to the big boys. (So much for Uncle Joe in 2020. Toastville.) I get the willies when I see two senators, blasts from the past, still doing their thing – Chuck Grassley from Iowa and Orrin Hatch from the great state of Ephedra. (Look it up.) Other senators are waiting to take their shot – Lindsey Graham, all the helium out of his psychic balloon since the death of John McCain, now just another (white) (male) Republican. Graham’s mind is already made up. He said so this past weekend. Then there is Mitch McConnell, probably the most outwardly vicious powerful senator I can remember, maybe going back to Joe McCarthy, supporting a cause I bet he doesn’t believe in, for the good of his party. They are all waiting to have a go at Dr. Blasey, knowing their window is closing to get Kavanaugh voted onto the Supreme Court to appease their base. Dr. Blasey’s allegation is tricky enough; we have all read and heard about the complications of memory, women recalling ugly things that happened, or that they now think happened. We also know many ugly things have happened. (See: Cosby, Bill.) Kavanaugh deserves a fair hearing, the presumption of innocence. What he also deserves is a detailed investigation by the FBI, now badly maligned by President Trump, who has his own legal troubles, shall we say. The New Yorker has published another article alleging harassment; a woman named Deborah Ramirez is claiming an ugly episode involving Brett Kavanaugh when they were both undergraduates at Yale. (The Times says it could not corroborate her claims in recent days, to the satisfaction of its own judgment.) In the New Yorker’s layered article, another woman is alleging misconduct by a young, entitled prep-school frat boy named Brett Kavanaugh with a reputation for drunkenness, at that time. None of this is easy. Reputations – lives – families – careers – are at stake. Twenty-seven years have gone by since Grassley and Hatch ran up the score against Anita Hill in the service of their party. Twenty-seven years. Where did the time go? I already had the creeps. They are getting worse. I am reminded of driving north from spring training that day, with black friends and white friends in two cars -- the looks of terror at some Holiday Inn in east Georgia, when they thought we were Freedom Riders rather than tired travelers, in psychic shock. How they hustled to accommodate us! In January, Black History Month, I wrote an essay about Martin Luther King, Jr. -- based on a radio documentary about King's connection to music, by his fellow Morehouse alumnus,Terrance McKnight of WQXR-FM in New York. That link is repeated as we approach the 50th anniversary of his death on April 4: www.georgevecsey.com/home/what-if-martin-luther-king-jr-were-alive-today Other people are remembering Dr. King this week. My friend Maria Saporta, who grew up with the King children in Atlanta, now issues the Saporta Report, about the business and life of Atlanta. She was previously the business columnist at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Saporta recently ventured to Memphis, where her friends' father was assassinated Her touching essay is linked here: https://saportareport.com/still-missing-martin-luther-king-jr-after-all-these-years/ And Lonnie Shalton, a "mostly retired lawyer from Kansas City who writes about baseball and other assorted topics," and is a good friend of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in that city, wrote about Dr. King. From Lonnie Shalton: I felt the need today to take a break from my Hot Stove baseball posts. Fifty years ago today, Martin Luther King delivered his last speech: “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” The following day, he was assassinated. I have written annual messages for the MLK holiday since 2002, and the one I sent in 2012 was about this speech. (Lonnie mentions a 2009 trip to Jordan, going to Mount Nebo, where Moses is said to have stood to view the Promised Land.) Fast forward from biblical times to April 3, 1968. Martin Luther King was in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers who were marching with a simple message: “I AM A MAN.” That night, at the Mason Temple, King gave what would be his last speech: "I've Been to the Mountaintop." King prophetically spoke of his likely early death and that he would not get to see the full fruits of his labor in the Civil Rights Movement. "I would like to live a long life; longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land." One of the Memphis hosts for that speech at the Mason Temple was Reverend Billy Kyles. The next day, Kyles drove to the Lorraine Motel to pick up King to take him to dinner. He joined King in his 2nd-floor room with Ralph Abernathy and went with King to the balcony to speak to supporters in the parking lot. A few seconds after Kyles left King alone on the balcony, James Earl Ray fired his shot. In the summer of 2011, Rita and I were in Memphis with our friends Larry and Diana Brewer. We visited the Lorraine Motel, which is now the "National Civil Rights Museum" featuring excellent exhibits on major milestones of the Civil Rights Movement. A compelling reminder of the times is a city bus that you can board, and when you sit near Rosa Parks, a recording is activated to tell you to move to the back of the bus. The museum tour begins with an introductory movie narrated by Reverend Kyles. At the end of the movie, we were informed that Kyles was in the building filming a piece with CNN newsman T.J. Holmes in anticipation of the opening of the MLK Memorial in Washington. We went to the second floor to watch the filming and then had the opportunity to visit with the gracious Reverend Kyles at almost the exact spot where he had been at that fateful moment in 1968. In the photo below, T.J. Holmes is on the left, Kyles is in the center and the two gentlemen on the right are retired sanitation workers who were among those 1968 marchers wearing "I AM A MAN" placards. The museum continues across the street to the rooming house from which James Earl Ray fired his shot. There are exhibits related to Ray's planning and capture, and we were reminded that Ray at the time was a fugitive from the Missouri State Penitentiary. Thanks to Terrance McKnight, Maria Saporta and Lonnie Shalton, for caring.

I was going to write about a heinous new development in baseball -- but other events intruded. As the Mueller investigation demands records from the Trump business, and the porno queen heads to court, the President shows signs of unraveling. In his pull-the-wings-off-flies mode, Trump had his garden-gnome Attorney General dismiss an FBI official just before his pension was official. On Friday evening, the retired general Barry McCaffrey issued a statement that Trump is a “serious threat to US national security.” Gen. McCaffrey fought in Vietnam, whatever we think of that war; Trump had spurious bone spurs. McCaffrey was later the so-called drug czar for the federal government, which is how I came to value his knowledge. So instead of writing about baseball, I am placing this note atop my recent posting because the ongoing comments are fascinating – from the Panglossian to the dystopian. I think it is important and life-affirming to be able to spot danger. Gen. McCaffrey has it. The majority members of Congress seem to have lost that ability. Meanwhile, Trump’s Russian pals keep pummeling the soft midsection of the U.S. while the President tweets and fires people long-distance, the coward. (This was my previous posting; comments ongoing.)

I haven’t posted anything in 12 days. Been busy. One thing after another. On Wednesday I stayed with the Mets-Yankees exhibition from Florida, even when people I never heard of were hitting home runs off people who won’t be around on opening day. But it was baseball, and really, in ugly times like this, isn't that what matters? Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling were going on delightful tangents after Darling said Kevin Mitchell had just emailed him. Kevin Mitchell – the guy the front office blamed for leading poor Doc Gooden and poor Daryl Strawberry astray? That guy. Terrible trade, Hernandez said. Ron and Keith meandered into tales of a nasty fight in Pittsburgh, started by my friend Bill Robinson, the first-base coach. The broadcasters recalled how Mitchell was destroying some Pirate, and both teams had to stop their usual jostling and flailing to save a life. The good old days. I loved the filibustering about 1986. The best impression I took from the three hours was the sight of Juan Lagares playing the sun, the wind and the ball with knowledge, grace, speed and touch. “That’s a real center fielder!” I blurted. Curt Flood. Paul Blair. Andruw Jones. Dare I say it, Willie Mays? Baseball. I was happy. * * * I need to write something but I keep getting distracted. I turn on the tube and think I see a traffic cam of an addled old man trying to cross Queens Boulevard -- the 300-foot-wideBoulevard of Death -- in my home borough of Queens. Is he carrying a baby as he lurches across 10 lanes of danger? The wind picks up. His comb-over flies up. Wait, that’s not any addled old man from Queens. What’s he carrying? It’s not a baby. He’s got the whole world in his hands. I watch with morbid fascination as he lumbers into danger. * * * I need to write something but I keep getting distracted. We’ve had two March snowstorms in a week. On Wednesday we lost power for five hours but my wife made instant coffee via the gas stove, and put together a nice supper, and we listened to the news on a battery-operated radio and then we found Victoria de los Angeles and “Songs Of the Auvergne," one of the most beautiful recordings we know. The juice went on in time for us to catch up with latest news about the porno queen and the Leader of the Free World. Gee, we didn’t have scandals like this with George W. Bush or Barack Obama. I watched for hours. * * * I need to write something but I keep reading instead. My old Hofstra friend, basketball star Ted Jackson, recommended I read “Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America,” by Patrick Phillips about rape charges and lynching and the forced exodus of blacks from Forsyth County, Ga., in 1912. As it happens, I have relatives, including some of color, who live just south of that county, now re-integrated in the northward sprawl of Atlanta. The denizens of that county in 1912 sound like the great grand-parents of the “very fine people” who flocked to Charlottesville last summer. It never goes away, does it? * * * I need to write something but I keep following the news. At the White House press briefing Wednesday, Sarah Huckabee Sanders spat out, with her usual contempt, the little nugget that the President had won a very, very big arbitration hearing involving the porno queen and $130,000 the President's lawyer shelled out from the goodness of his heart. Oops, the jackals of the press did not know about that. Thanks to Sanders, now they do. I got the feeling Sanders might be leaving on the midnight train for Arkansas. I envision Sanders trying to hail a ride on Pennsylvania Ave. but a stylish woman with a teen-age boy in tow beats her to the cab. That woman is leaving on the midnight plane for Slovenia. * * * I need to write something, but stuff keeps happening. (Note: This piece was filed Friday morning, just before John McCain announced he could not support this vicious bill. I have had great respect for McCain since I met him years ago. His action Friday may have doomed the legislation -- for now -- but these people keep coming back for their money.)

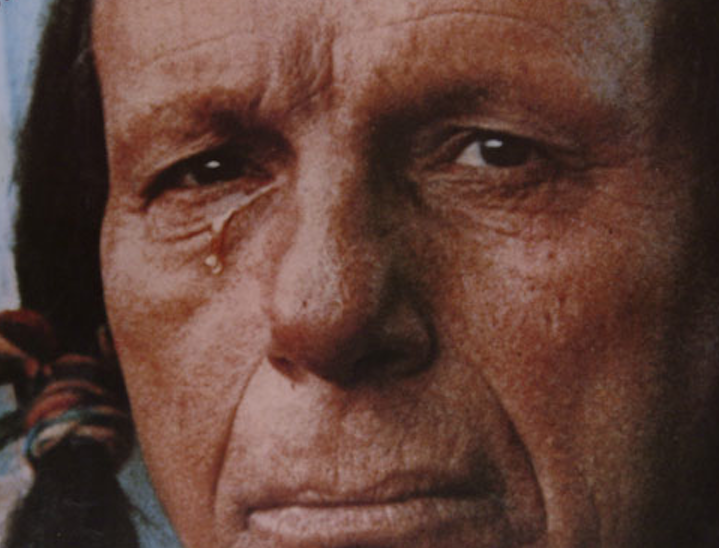

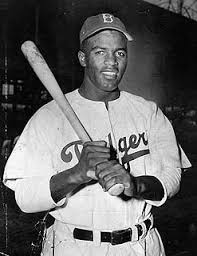

Lately, I’ve been seeing the image of the Native American with one tear rolling down his cheek. It was a highly popular commercial, for the ecology, from Earth Day, 1971. The man had paddled down a pristine river and sighted a modern Apocalypse of debris. That’s how I feel these days. It’s not just the natural disasters pounding Texas and Florida and the Caribbean and Mexico, places we know and love. It’s deeper. It’s the vision into the heart of darkness. I have dealt with the election of a cruel, ignorant and disturbed human being, believing he will be out within 18 months. He’s a symptom of something worse. The teardrop in my mind comes when I see stone-hearted members of Congress preparing to vote to take away health care from millions of people who need it the most -- fellow Americans, whatever that means anymore. I see politicians – and by that I mean Republicans – lobbying for votes, to stiff the poor and the sick. They are doing it for their donors, the Koch Brothers and villains like them, who want tax breaks, and do not care how they come, even at the penalty of taking away surgery from the ill and shelter for the aged. These donors would, essentially, kill for money, and so would their lackeys in Congress. Lindsey Graham. For a while, I thought he was showing touches of humanity but now he is front and center for the White Citizens Council, some of them doctors, for goodness’ sakes, who shuffle wordlessly behind Head Kleagle McConnell. They want money so they can keep going. Jimmy Kimmel is wise to this Cassidy guy. I hope Kimmel's rants do some good. Until McCain made his statement Friday, I could not count on three Republicans in the Senate to vote for the poor. Plus, I can think of a Democrat or two who would shaft people in their own states, for money. They do not want to care for their fellow humans. And they have the backing of some large and oily religious lobbies. I can remember when Americans told each other we were the good guys who helped win two World Wars. If you overlooked the Civil War, the war that has never ended, it was a workable image. This current collective meanness has been coming on for a while. It began when the McConnell-Boehner-Ryan coalition sabotaged Barack Obama for the crime of Presiding While Black. It’s about race, a lot of it. I’ve gotten pretty tough in my old age. I ascribe to the Iris Dement song, “No Time to Cry,” about how her father died and she had to keep going. But now I'm walking and I'm talking, Doing what I'm supposed to do. Working overtime to make sure I don't come unglued. I guess I'm older now and I've got no time to cry. Then I remember the Native American, so proud, so stoic, seeing what others are doing to his world. One tear. (Footnote: the man in the commercial, who went by the name of Iron Eyes Cody, was actually of Sicilian ancestry, Espera Oscar de Corti, and grew up in rural Louisiana. He portrayed Native Americans in movies, and married one in real life. He looked the part well enough that I remember his tear, 46 years later.) On Saturday, every major-leaguer will wear No. 42, to commemorate Jackie Robinson, the first African-American in the majors in the 20th Century.

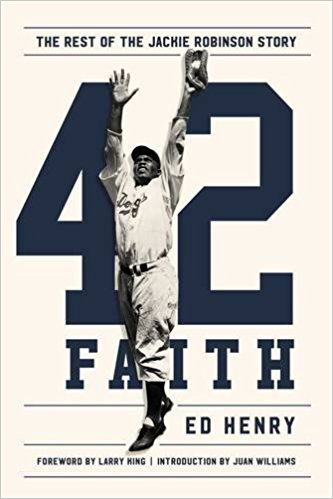

This will be the 70th anniversary of Robinson’s debut in Ebbets Field, Brooklyn – the beginning of a grueling season, a grinding decade. Jackie Robinson would die at 53. Many people think the ordeal heightened his diabetes, hastened his death. In a real way, he gave his life for a cause. This sense of Robinson as vulnerable point man for equality is never more relevant than in a time when Americans seem to be questioning their direction – when the Roberts Supreme Court can negate previous civil-rights legislation, letting us know that things are just fine now, we don’t need all those rules bolstering people’s rights to vote. By some cosmic happening, the Robinson anniversary and the return of baseball take place in the spring, in the time of Passover and Easter, celebrations of survival. Robinson’s own beliefs – the power that kept him going – is currently explored by Ed Henry in his new book, “42 Faith,” published by Thomas Nelson. Henry is the Fox News Channel chief national correspondent (and a friend of mine.) Henry is too young to have seen Robinson play or meet him but in his busy life he has admirably sought out people and places where Robinson’s history can be felt. Henry explores the magnetic pull of the ball park that used to be in Flatbush; the vanished hotel in Indiana where Branch Rickey gave shelter to the black catcher on his college team, the still-standing Chicago Hilton where a wise Dodger scout named Clyde Sukeforth interviewed a Negro League player named Robinson. Holy places, in a way. The story has been well told by Arnold Rampersad and Steve Jacobson and Roger Kahn, if not with this overt angle on faith: Robinson was a mainline Protestant who relied on his pastor, who taught Sunday school, who saw life through a framework of Christianity. He was sought out for the Brooklyn Dodgers by Branch Rickey, a man of religious dedication – who did not go to the ballpark on the Sabbath -- who had no qualms about wheedling his best players out of a thousand here, a thousand there. Aging Brooklyn heroes like Carl Erskine and Vin Scully recall the strength and complexity of Robinson, and aging fans recall the example of Robinson holding his natural fire, to establish himself, and his people. This was a big deal, the coming of Jackie Robinson. I remember being home in the spring of 1947 when my father called from the newspaper office to say that our team, the Dodgers, the good guys, had just brought up Robinson from the Montreal farm team, that he would open the season in Brooklyn. We (white, liberal) celebrated. Every year the major leagues celebrate with No. 42 on every uniform. Thanks to an inquiring journalist, the story goes on. Nice to be back in the NYT, twice in one day – courtesy of two hard hitters, Gordie Howe and Muhammad Ali. The Times resurrected a column I did in 1996, the morning after Ali’s stunning appearance, carrying the Olympic torch. Then by coincidence, they also used a column I prepared a year ago, when Gordie Howe had a stroke. Two great athletes in vastly different sports, one expanding his strong personality over the years, the other subordinating himself to his sport and his home of Canada. * * * Some thoughts on the farewell to Ali: I was asked to provide some color for the funeral for the lively New York television station, NY1, which, alas, I cannot access on Long Island due to cable rivalries. I spent a pleasant afternoon with Roma Torre, the anchor (and daughter of epic New York Herald Tribune journalist Marie Torre.) She let me share some of my glimpses of Ali, in Louisville, where I lived for a few years, and at boxing events. In between, we watched the farewell to Ali. It was fascinating to see Ali as touchstone for the religions and passions and politics of so many disparate people – the activist, Rabbi Michael Lerner of New York, Chief Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Nation (unidentified as a great Syracuse lacrosse player and teammate of another Greatest, Jim Brown), and so many Ali women, with his verbal gifts and his beauty. When I called home, my wife raved about Billy Crystal, for catching Ali (and Howard Cosell) just perfectly, telling how Ali stopped jogging at a swank country club in the New York suburbs after Crystal mentioned that the place was known to exclude Jews. The one over-riding impression of Ali was a man who did righteous things, in small and hidden and often funny ways – in contrast to his public bombast and occasional cruelties. I liked him even better afterward. * * * My column on Ali at the Atlanta Olympics revived my memory of how it came about – as pure afterthought, blessed inspiration, the next morning, on three hours of sleep, when I had committed to covering the first gold medal of the Games, for shooting. My strongest memory is of an Iranian woman in full chador, competing, making it a truly universal Olympics. But as I banged out my column smack on deadline for the first Sunday edition, I realized we (I) needed to get back to what it mean for Ali to materialize like that, high above the stadium, like a comet, glowing brightly. I consulted with our Olympic bureau chief, my pal Kathleen O. McElroy, and we got a short column done for the second edition, and for posterity. How sweet that the NYT would find it again this week (with a photo by the great Doug Mills, now taking photos of President Obama in the White House.) * * * It touched me to see Ali buried in Cave Hill Cemetery, in one of the most beautiful corners of Louisville – steep hills, limestone outcroppings, Beargrass Creek flowing through it, with tombs of many famous Louisvillians – veterans on both sides of that ghastly Civil War, plus George Rogers Clark, Joshua Speed, Barry Bingham Sr. and Barry Junior (who was so hospitable to me in my two-year stint as Appalachian Correspondent for the NYT) and Col. Harland Sanders (whom we once saw eating ice cream one night – in a Howard Johnson’s.) We almost bought a house in that funky old neighborhood of the Highlands – always sorry the deal fell through -- and when I returned for the Derby I would duck the Oaks on Friday and go jogging in the Highlands, including through Cave Hill Cemetery. When it quiets down, I’ll go back and pay respects to Ali. RIP. (Above: Bud Collins Interviews Muhammad Ali, 1968.) When the Times called and asked me to write something about Ali, I stuck close to the theme of personal fleeting encounters with Ali – once upon a time in America.

There was no time or space for two other impressions of Ali, so I am getting to them here, both from 1996. The Anniversary. In March of 1996, I drove down to North Philadelphia to Joe Frazier’s gym, to talk about the 25th anniversary of their first fight in 1971. I knew Ali could no longer discuss that fight, but Smokin’ Joe could. I found him smoldering, resentful over the way Ali had pulled racial attitudes on him, calling him a gorilla and mocking the way he spoke. "I won that fight," Frazier said about 1971. "Guess I won the other two, also. I'm here talking to you, right?" He was crowing about still being able to work out and drive a car and talk to me, quite intelligently, his speech slightly difficult to follow because he grew up in a coastal region of South Carolina where the African dialect of Gullah was an influence. I could understand Smokin’ Joe just fine. He felt that Ali – sometimes he called him “Clay,” his birth or slave name – was duplicitous, manipulative, vicious. Two of Frazier’s children were at the gym – Marvis, preacher/boxer/companion, and Jackie Frazier-Lyde, his athlete daughter, now a municipal judge. Both were a tribute to Joe, and to their mother, adults with brains and compassion. They told him, Dad, you have to get over it. I knew Joe and Marvis to be good people. They had recently driven from Philly to Long Island in a major January snowstorm to attend the funeral of a dear friend, arriving at the synagogue after the service and staying a long time. I felt for Smokin’ Joe, who passed in 2011. In the mirror of time, Ali was diminished by his treatment of Frazier. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/03/sports/perspective-boxing-25-years-haven-t-softened-blows-frazier-finally-earned.html?pagewanted=all The Olympic Torch. A bunch of reporters were sitting in the press tribune at the Olympic Stadium, speculating on who would have the honor of carrying the torch on its final segment – a famous athlete? A King or a Carter? An artistic symbol of the new South? I don’t think any of us were prepared for the slow, deliberate trudge of the figure in white, one hand quivering, one hand carrying the torch up a narrow pathway. When we realized who it was, we gasped and then we did something banned in press boxes – we stood and exchanged high fives. Muhammad Ali. Perfect. Everybody understood the forces within that diminished figure – the draft, the conversion, the hyperbole, the beauty, the fights, the path from alien radical to stricken native son. That happened on a Friday night, too late for the Saturday paper. A few hours later for the Sunday paper I wrote this short, personal, emotional tribute less to Ali himself than to the Atlanta organizers who, perhaps to my shock, totally got it. (With a major nudge from Dick Ebersol of NBC.) http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/sports/year_in_sports/07.19.html * * * (Finally, my thanks to so many people who have responded to my column in the Times. My praises to the professionals who produced and distributed the Ali tribute in about 170,000 copies of the final edition of the Saturday paper – including one on my doorstep.) Sometimes you witness history -- but it looks just like a basketball game.

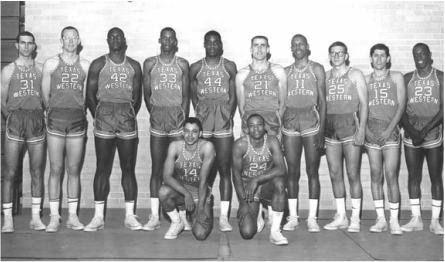

That’s what happened with me, 50 years ago, when I covered the final weekend of the NCAA tournament. Nobody called it March Madness back then. It was merely the semifinals and the finals. The final was between the all-white University of Kentucky team and Texas Western, which usually played seven men, all of them African-American, or Negroes, the name of the time. Everybody knew it was a big deal – nothing like the March on Washington in 1963 or anti-war protests in that tumultuous decade. This was a game, a final. Nobody dug out details to prove it was the first all-white vs. all-black final, although everybody sort of knew it. There was no hubbub on the Web. Actually, there was no Web. Get this: the N.C.A.A. final Saturday afternoon was shown on tape delay that evening. I was there, a young reporter for Newsday, driving down to Florida to cover spring training, and my boss suggested stopping off in Maryland to cover the games. Of all the papers in the land, “we” at Newsday (transient reporters switch their “we” just as ballplayers do) were probably the most socially conscious sports department in the country, writing about race and gender and money and politics. Before the final, our perceptive columnist, Stan Isaacs, wrote of Texas Western: “All of the first seven are Negroes. That shouldn’t be significant one way or another, except that many people make it noteworthy with snickers about the ethnic makeup of the team.” In the University of Maryland field house there was no overt tension – just black players coming out physically, setting a tone. Our professional code said no rooting whatsoever, but I must have been emotionally involved in the game. I come from a liberal New York family that idolized Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson. My dad called home from his newspaper office in 1947 to tell us our Brooklyn Dodgers had officially elevated Jackie Robinson. Yet the stories from opening day hardly mentioned that Robinson was the first black player in the major leagues since the 19th Century. Imagine how that event would be covered today. Fans and reporters watched Texas Western block and defend and rebound, winning the national championship by a 72-65 score. And afterward I wrote that six of the seven Texas Western players were from up north –suggesting they were unafraid, had a point to make. “All seven players who got into Saturday’s final game are Negroes,” I wrote. “They play well together and Kentucky did not seem ready for the way they play.” I watched for details of the upset – handshakes, politeness, all around. Kentucky’s Pat Riley (from upstate New York) and Louie Dampier (from Indianapolis) visited the winners’ locker and congratulated them. I recall how Adolph Rupp, the fabled coach of Kentucky, unpopular with us in New York, exuded respect, chirping that Texas Western was well coached, played hard, deserved to win. Rumor says he raged, used racial words in his own locker room, but Riley, perhaps being loyal to his old coach, has told me that Rupp was sportsmanlike that day. Four years later, I moved to Kentucky as a regional news reporter for The New York Times. By then, Rupp had used black walk-on players; I drove to Lexington to do a story about his first black scholarship player. I remember Rupp’s jovial chirping at me – “How does a feller from New York like our little part of the world?” He had gone with the times, like Bear Bryant and other coaches. (Confession: I became hooked on UK from living there; when Duke’s Christian Laettner took his killer shot in 1992, I instinctively jerked my head in blatant body English, to no avail.) Over 50 years, Texas Western-UK has come to have epic meaning. (The winning school is now named University of Texas, El Paso.) Thirty years after the game, I wrote a reprise for The Times. Recently, the surviving players have been talking about it leading up to the actual anniversary on March 19. So much has come from that low-key day in Maryland in 1966 – players like Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Michael Jordan, coaches like John Thompson and Nolan Richardson, maybe even a cool former Harvard Law Review president with his lefty moves on the White House court. If reporters like me typed gingerly that day -- if whites did not overtly sulk and blacks did not overtly exult – chalk it up to the unspoken understanding that this was only a game, in a time of more momentous events all around us. There are many things wrong with Donald Trump. Many things. But whether his family name was changed is not one of them.

Every day something bad comes out about Trump – his faux “university,” his ludicrous litany of products real and discontinued, and worst of all, the public events where Trump’s people sucker-punch protestors who just happen to have dark skin. Apparently, he lied about consulting police before cancelling his rally in Chicago Friday night. Trump is, to use his own fourth-grade word selection, a nasty, nasty guy. (When he says “dude” it's a code word for blacks.) I was calling some of Trump’s sucker-punch supporters Brown Shirts long before I heard that his family name may have been altered a generation or three ago. Brown Shirts do not depend on a discarded name from the other side. Now it turns out that the Trump family from a posh section of Jamaica Estates, Queens, may have been named Drumpf back in Germany. Trump, typically, has been known to claim he had Swedish origins. Well, who believes him on anything? Into the mix comes a British comedian selling ball caps (at cost) that say “Make Donald Drumpf Again” – a twist on Trump’s subliminally racist slogan. The first lot of ball caps sold out. I don’t find John Oliver funny. I came upon him in 2014 when he was goofing on the American interest in the soccer World Cup, those silly people. This was after a quarter century of American involvement in the great event, with pubs and television ratings flourishing during the World Cup in Brazil. But Oliver yukked it up, giving me the impression he has a tin ear about the country where he makes a considerable living. (I gather, to his credit, he is also having fun with the scandals of FIFA, the world soccer body.) Fact is, the basic act of changing a name, legally or otherwise, is part of the American experience, part of assimilation. Changing names is as American as apple strudel. Some people changed their names to make them sound more American. But I grew up a yooge half mile away from Trump’s posh enclave, and I knew German-Americans up the block who kept their name – and their vestigial accents, harder to shed – shortly after the War, with no need to hide their life’s journey. My soccer captain at Jamaica High spoke German before he spoke English, he told me the other day. Nowadays, the newer waves, the Garcias and the Patels, do not change their names; we have moved on. We also change pronunciations. The Hungarian-American family that adopted my father had long since anglicized their pronunciation to VES-see, but as a tour guide in Budapest once lectured me, my surname is quite familiar there, and is pronounced VAY-chay. (Bud Collins was the only person who called me VAY-chay. Bud knew that stuff.) What’s in a name? Donald Trump is a creep, a dangerous creep. If his family changed its name, a comedian sniggering about it on the tube does not help the dialogue.  Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953) It is Black History Month, which means I always learn something. This Black History Month has caused me to re-think my position on the first woman, or women, who should be on an American bill. But first: Three years ago, Terrance McKnight of WQXR-FM did a documentary on a composer I had never heard of, Florence B. Price. The other night, PBS ran a visual documentary on Price, and by now her music was more familiar to me, ranging from traditional classical to black gospel. One of the experts (mostly black, via Arkansas Public Television) compared her to one of my favorites, Antonin Dvorak, who used folk music (in the deepest sense of the phrase) of two worlds, Bohemia and America. Artists generally have it hard, but black artists have it harder. The PBS documentary showed how Price was inspired by classical music but segregation and economics held her back. She always had to be double good. (Sound familiar?) In one pathetic episode, already accomplished, Price wrote a letter to Serge Koussevitzky, the legendary director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, asking to compose for him, and she felt the need to call attention to being “Colored.” He never wrote back. Yet she had her triumphs. Mainstream conductors and critics and performers took her seriously, notably in her adopted home town of Chicago. In one of the great moments in American history, Marian Anderson performed at the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial, April 9, 1939, after Eleanor Roosevelt had forced the issue. Anderson sang a hymn by Florence B. Price, her friend. In the Arkansas documentary, an elderly black woman recalls, half a century later, being young and seeing a black woman singing to 75,000 people. The old lady daubs her eyes with a handkerchief. I bet you will, too. How hard it was, how hard it is, to be black in America. Just look at the dignity of people who have been poisoned in Flint, Mich., because of the incompetent and heartless regime of a latter-day plantation massa, Gov. Rick Snyder. But there are triumphs. Look at the lovely front-page photo of President Obama, speaking at a mosque in Baltimore, calling for a cessation of prejudice, as children smile in awe. We have seen those smiles on black service members when Obama visits the troops and on black citizens when Obama goes out in public. So there is that. But Black History Month reminds us how hard America has been on any black who aspired. That is why I am wavering in my position that Eleanor Roosevelt should be on a bill. I think she may be the greatest woman yet produced by the U.S.A., but her greatness may have been in her advocacy of the underprivileged, for people of all colors. Now I think the next bill (lose Andrew Jackson off the 20, not Alexander Hamilton off the 10) should be a tribute to the great women of color in America. Who? How many? I leave that to historians. But when that glorious bill arrives, somebody should play the classical music of Florence B. Price. Below: The multitalented Terrance McKnight accompanies Erin Flannery in “To My Little Son,” by Florence B. Price: Kathleen McElroy used to be the deputy sports editor at the Times. She was calm and smart and knew her sports, including the one called foo’ball. She is, after all, from Texas.

She was running our Olympic bureau in Atlanta in 1996 when the bomb went off after midnight, and she took charge, dispatching us into the darkness and the confusion. Later she moved up at the Times, editing the Sunday and Monday editions. She was the duty officer when the Columbia exploded in 2003. Somewhere along the line, she became part of our family, either my third sister or my third daughter -- not that she lacks for family, with sisters galore and the memory of Lucinda and George McElroy, both formidable. Kathleen’s middle initial is O. Not everybody knows that it stands for Oveta, as in Oveta Culp Hobby, who operated the Houston Post for decades – and under whose leadership George McElroy became the Post’s first African-American columnist. We always figured Kathleen was one of those out-of-towners who arrive in New York, scout out the restaurants and shops, discover a nice apartment, and stay forever. They are some of the best New Yorkers. But foo’ball may have been a tipoff. She is a Southwestern person. Kathleen chose to leave the Times, earning a scholarship to the University of Texas. This fall she defended her dissertation -- "Somewhere Between 'Us' and 'Them' -- Black Columnists and Their Role in Shaping Racial Discourse" -- and received her Ph. D. She is now teaching journalism at Oklahoma State University, with emphasis on the African-American experience. The other day Kathleen sent me a text message that said, “I want to make a difference.” We miss her at family gatherings, and expeditions around the city for the perfect barbecue or the perfect curry. She will make a difference. We’ve managed to catch some of the wonderful Ken Burns documentary on the Roosevelts on Public Television – a great vision of America, as vital as today’s front page.

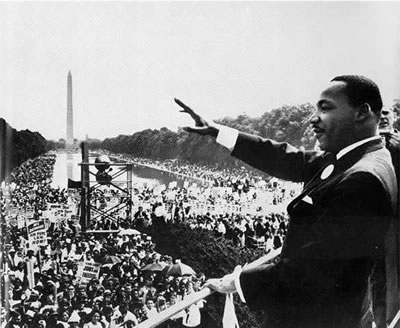

In the parts we’ve seen, I recalled my slight personal connections to Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt. As a young reporter, I interviewed Theodore Roosevelt’s younger daughter, Ethel Carow Roosevelt Derby, by then in her eighties, in Oyster Bay, Long Island. I almost blew the interview right away by referring to her father as a hunter. He was not a hunter, she snapped; he was a sportsman. (I had seen those heads in the museum.) The documentary refers to him often as a hunter. Mrs. Derby would not be amused. As a five-year-old, in a household that loved Franklin and Eleanor, I was taken to his campaign through New York on a miserable rainy day, Oct. 21, 1944. I recall being on a hillside, watching the motorcade on Grand Central Parkway. The car was open, and his face was pasty white. The web says he told the crowd in Ebbets Field that he had never been there before, but claimed he had grown up a Brooklyn Dodger fan. He died six months later. That romp through the boroughs did not help. Eleanor Roosevelt was a staple in the politics and affection of my family. Later we read books about how she pressured her distant husband into absorbing information about the plight of so many Americans. Two things I have heard about Eleanor Roosevelt lately: When I was working on the Stan Musial biography, I learned that Musial had joined a tour for John F. Kennedy in 1960, which included Angie Dickinson. The actress became a knowledgeable source about that campaign, telling me how she was addressing a crowd in the New York Coliseum on the Saturday before the election: “My big claim to fame is that I was making my speech, and I heard a hush and they wheeled in Mrs. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, and I got to say, ‘What I have to say isn’t important’– I almost was finished – ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the great Eleanor Roosevelt,’ and I got to introduce her.” Dickinson’s respect, half a century later, was palpable. I learned something about Mrs. Roosevelt recently while reading a very nice history book – Indomitable Will: Turning Defeat into Victory from Pearl Harbor to Midway, by Charles Kupfer, an associate professor at Penn State Harrisburg. In the first shocking hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the President assembled advisors and friends in the White House, including Edward R. Murrow, the CBS broadcaster (this was back when networks maintained serious news organizations.) FDR picked the brains of Murrow, who had access to the back rooms of the White House. Eleanor Roosevelt, who had fought for millions of poor people, who had fought for civil rights and women’s rights, cooked some eggs for Murrow. Kupfer’s book had me, right there, on Page 22. The Burns documentary had me as soon as I saw the insecure half-smile of young Eleanor Roosevelt, before she discovered the activist within. Her wise eyes take the measure of a country that has failed its people. She spends her own money to build experimental communities in deepest West Virginia. She sets an example. The camera cannot find too much of her. She reminds us of the men who went to war, the women who went to work, the blacks who wrote letters to the President, asking for help. Her face reflects the country many of us thought we were, or could have become. As I wrote this, I flashed on something else about the Burns documentary: Elizabeth Warren reminds me of Eleanor Roosevelt. The networks and the papers are gearing up for the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington on Aug. 28. I saw the saintly John Lewis on television the other night. Memories kick in. I was covering the Mets in Pittsburgh, and watched the march on television during the day, captivated by the mood, the words, the faces. Then I got on the bus from the Hilton, down by the famed confluence, to funky old Forbes Field up on the hill. At some point I got into a conversation with Maury Allen of the Post and Jesse Gonder and Alvin Jackson of the Mets, who had all been watching in their rooms. I’ve always treasured this memory of four people standing around the clubhouse, so enthused about Martin Luther King and the other speakers, and the people who had come so far, the joy and hope we felt. I’d forgotten that Jackson was the starting pitcher that night, lasting four and two-thirds innings against his old club, taking the loss in a 7-2 defeat. Gonder pinch-hit for Choo Choo Coleman with two on and no out in the ninth and hit into a force play. Roberto Clemente went 3-for-4 and drove in 3 runs. I can’t remember if we asked him about the march after the game. I’d like to think we did. Throughout the bad times and the good times, the memory remains of that march. The four of us had been sure, as the Sam Cooke song would say a few months later, a change was gonna come. Nowadays, the sour faces on Cantor, McConnell, Paul and Boehner seem straight from the bad old days. And we are assured by Chief Justice John Roberts that things are so good that we do not need a voting rights law anymore. Governors and legislatures do their best to deny access to voting. Fifty years ago I stood around a clubhouse with three friends and talked about the March on Washington. The box score from that game: http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B08280PIT1963.htm The history of the Sam Cooke song: http://www.americansongwriter.com/2009/07/behind-the-song-a-change-is-gonna-come/ A more recent story about the March on Washington: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/28/us/politics/28race.html?_r=0 Ladies and gentlemen, the late, great Sam Cooke: The national treasure Stevie Wonder says he is not going to perform in Florida or any other state with a right-to-blow-away-the-other-guy-if-you-don’t-like-the-look-on-his-face law.

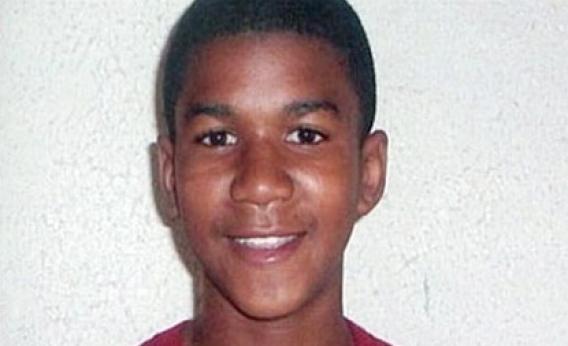

With all due respect, I think Stevie ought to sing one song in Florida and other trigger-happy states. That would be “Saturn,” released in 1976 in his “Songs in the Key of Life” album, about an interplanetary visitor who is going back home “where the people smile.” The singer is boggled by the ecological waste and wars of this alien planet. In this version, Stevie describes earthlings “with a gun and Bible in your hand.” In some lyrics on the Web, that line is absent. Guess it cuts too close to the bone. There is a lovely youtube version by Panoply – they could splice in some facial photos of Rick Perry, Jan Brewer, Rick Scott and that thoroughly character-less smirk of Gov. Ultrasound of Virginia. The key sentence is, “Tell me why are you people so cold.” Sing it, Stevie: http://www.youtube.com/watch?sv=WnVGczH8rWk Saturn Packing my bags -- going away To a place where the air is clean On Saturn There's no sense to sit and watch the people die We don't fight our wars the way you do We put back all the things we use On Saturn There's no sense to keep on doing such crimes There's no principles in what you say No direction in the things you do For your world is soon to come to a close Through the ages all great men have taught Truth and happiness just can't be bought-or sold Tell me why are you people so cold I'm...... Going back to Saturn where the rings all glow Rainbow, moonbeams and orange snow On Saturn People live to be two hundred and five Going back to Saturn where the people smile Don't need cars cause we've learned to fly On Saturn Just to live to us is our natural high We have come here many times before To find your strategy to peace is war Killing helpless men, women and children That don't even know what they are dying for We can't trust you when you take a stand With a gun and Bible in your hand And a cold expression on your face Saying give us what we want or we'll destroy I'm...... Going back to Saturn where the rings all glow Rainbow, moonbeams and orange snow On Saturn People live to be two hundred and five Going back to Saturn where the people smile Don't need cars cause we've learn to fly On Saturn Just to live to us is our natural high..... http://www.metrolyrics.com/saturn-lyrics-stevie-wonder.html My extended family includes children the same color as Trayvon Martin, only slightly younger.

Two of them are young men who could easily be walking around their neighborhood outside a major southern city, with a bag of candy in their hands. Their lives became a little more jeopardized Saturday night when the jury ruled George Zimmerman not guilty for starting trouble with a gun on him, courtesy of our gun culture. I understand the legal concept of reasonable doubt, but I have trouble with it when the oh-so-reasonable defense attorney (with his Queens accent) is willing to do his own racial profiling of a teen-age witness as a Haitian. Got that. Haitian. Kenyan. Outsiders. Not "us." That’s where we are going in this country – brave vigilantes walking around loose, plus long voting lines in poor districts, and the cuts in food stamps and planned parenthood, and other blatantly malicious acts. I firmly believe that Zimmerman acquired his courage not only from the big iron he was packing but from the message from the yowlers on the talk radio and the Murdochite channels, plus members of Congress – the Boehners and McConnells, the Cantors and Pauls -- who rule with a smirk, letting everybody know they are not cooperating with that Kenyan Socialist. That’s been going on for more than four years. The tone is set. Zimmerman is just a symptom. *-- Walking With Skittles As the holder of an Irish passport (as well as my American passport), I think I can safely ask just exactly what Bill O’Reilly is trying to say.

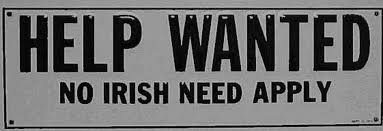

O’Reilly tried to wax profound last week after President Obama was re-elected with help from African-American and Hispanic votes. (One perky guest on MSNBC suggested a new motto for the Republican party: “Hello, Brown People.”) On Election night, O’Reilly said: “It’s a changing country, the demographics are changing. It’s not a traditional America anymore, and there are 50 percent of the voting public who want stuff. They want things. And who is going to give them things? President Obama.” O’Reilly added, “The white establishment is now the minority.” In noting the shift in America, O’Reilly seemed to be harking back to some golden era in America when the Cabots and the Lodges sat around the Boston Common and sang Kumbaya with the Flynns and, dare I say it, the O’Reillys. Was there ever a time in America when we were all just one happy family? After the settlers took the country away from the native Americans, that is. There were always newcomers to the land and the voting booths. They were noticeable by their clothes and their accents, if not their color. It isn’t quite clear to me whether some of my Irish ancestors (on my maternal grandmother’s side) ever ran into help-wanted signs that said NINA – No Irish Need Apply. Did those signs actually exist in large numbers in the 19th Century, as some people claim? In a way, it doesn’t matter. There are always newcomers, always outsiders. And it’s funny how new people want things, like work and housing and education and a chance to vote, without public officials in Ohio and Florida making it tough for them. O’Reilly seemed downright lachrymose when confronting the new reality – that voters of color now tilt the majority and helped re-elect a candidate who, despite being Kenyan and Muslim and, worst of all, an introvert, just might be the smartest person in the political room. The country keeps changing. Always did. Never touch anything in a store.

I still remember an African-American colleague telling me what she warned her two sons, decades ago. When they went to a department store or a toy store in New York, they were under strict orders to keep their hands at their sides, lest somebody get the wrong idea. Knowing how people love to touch things – and how hands-on is tolerated as a normal part of business – I could only cringe at the double standard my friend had to inculcate in her sons. The perceptions are still out there, even with an African-American president in the White House. Or maybe because of it. Take back our country. That sentiment careens around the Internet. What is worse is that versions of it are put forth by elected officials like Eric Cantor, the man with the most sour expression in Congress, who recently said Mitt Romney would “get us back on track.” Everybody knows the code. It was no accident that Cantor echoed the resentful tone that has been going around since November of 2008. The Trumps and Palins and McConnells of the country have been treating the president as an interloper, an outsider. Wonder why. I have no way of knowing what was bouncing around in the mind of George Zimmerman, 28, who allegedly followed and killed Trayvon Martin, 17, in Florida three weeks ago. Was this volunteer vigilante hopped up by the rhetoric in Congress and the campaign trails, that things are not quite right at the moment? Or does the traditional racist undertone of the country survive on its own, without blatant help from prominent politicians? Any of us with friends and relatives of color know the double takes and the stares. Children, particularly boys, are warned to watch their step when they go out. The photos of Trayvon Martin will break your heart. The sweet trusting smile. Surely, this young man heard the warnings from loved ones to be careful out in public. Even then, with the gun laws and the stand-your-ground law in Florida and the inflamed rhetoric going around, any caution Trayvon Martin had learned in his 17 years was not enough, as he ran into a stranger with his own notion of taking something back. Wat Misaka did me the honor of calling back Monday night and giving his viewpoint on Jeremy Lin.

We haven't seen each other since the summer of 2009, when he saw his name on a 1947-48 team plaque outside the Knicks' locker room. Misaka's comments are up and running on the NY Times site.On Tuesday night, Lin hit a 3-pointer in the final second for a 90-87 victory. I just looked it up: because of the strike, the Knicks don't play in Utah in this short season. Wat Misaka is going to have to do his rooting via the tube. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/15/sports/basketball/knicks-pioneer-roots-for-the-underdog-in-lin-george-vecsey.html?ref=sports |

Categories

All

|