|

Sometimes you witness history -- but it looks just like a basketball game.

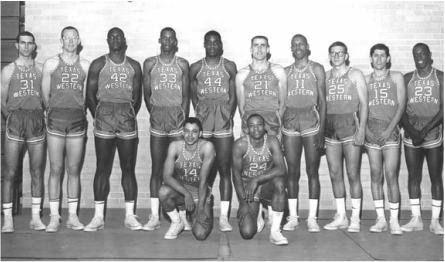

That’s what happened with me, 50 years ago, when I covered the final weekend of the NCAA tournament. Nobody called it March Madness back then. It was merely the semifinals and the finals. The final was between the all-white University of Kentucky team and Texas Western, which usually played seven men, all of them African-American, or Negroes, the name of the time. Everybody knew it was a big deal – nothing like the March on Washington in 1963 or anti-war protests in that tumultuous decade. This was a game, a final. Nobody dug out details to prove it was the first all-white vs. all-black final, although everybody sort of knew it. There was no hubbub on the Web. Actually, there was no Web. Get this: the N.C.A.A. final Saturday afternoon was shown on tape delay that evening. I was there, a young reporter for Newsday, driving down to Florida to cover spring training, and my boss suggested stopping off in Maryland to cover the games. Of all the papers in the land, “we” at Newsday (transient reporters switch their “we” just as ballplayers do) were probably the most socially conscious sports department in the country, writing about race and gender and money and politics. Before the final, our perceptive columnist, Stan Isaacs, wrote of Texas Western: “All of the first seven are Negroes. That shouldn’t be significant one way or another, except that many people make it noteworthy with snickers about the ethnic makeup of the team.” In the University of Maryland field house there was no overt tension – just black players coming out physically, setting a tone. Our professional code said no rooting whatsoever, but I must have been emotionally involved in the game. I come from a liberal New York family that idolized Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson. My dad called home from his newspaper office in 1947 to tell us our Brooklyn Dodgers had officially elevated Jackie Robinson. Yet the stories from opening day hardly mentioned that Robinson was the first black player in the major leagues since the 19th Century. Imagine how that event would be covered today. Fans and reporters watched Texas Western block and defend and rebound, winning the national championship by a 72-65 score. And afterward I wrote that six of the seven Texas Western players were from up north –suggesting they were unafraid, had a point to make. “All seven players who got into Saturday’s final game are Negroes,” I wrote. “They play well together and Kentucky did not seem ready for the way they play.” I watched for details of the upset – handshakes, politeness, all around. Kentucky’s Pat Riley (from upstate New York) and Louie Dampier (from Indianapolis) visited the winners’ locker and congratulated them. I recall how Adolph Rupp, the fabled coach of Kentucky, unpopular with us in New York, exuded respect, chirping that Texas Western was well coached, played hard, deserved to win. Rumor says he raged, used racial words in his own locker room, but Riley, perhaps being loyal to his old coach, has told me that Rupp was sportsmanlike that day. Four years later, I moved to Kentucky as a regional news reporter for The New York Times. By then, Rupp had used black walk-on players; I drove to Lexington to do a story about his first black scholarship player. I remember Rupp’s jovial chirping at me – “How does a feller from New York like our little part of the world?” He had gone with the times, like Bear Bryant and other coaches. (Confession: I became hooked on UK from living there; when Duke’s Christian Laettner took his killer shot in 1992, I instinctively jerked my head in blatant body English, to no avail.) Over 50 years, Texas Western-UK has come to have epic meaning. (The winning school is now named University of Texas, El Paso.) Thirty years after the game, I wrote a reprise for The Times. Recently, the surviving players have been talking about it leading up to the actual anniversary on March 19. So much has come from that low-key day in Maryland in 1966 – players like Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Michael Jordan, coaches like John Thompson and Nolan Richardson, maybe even a cool former Harvard Law Review president with his lefty moves on the White House court. If reporters like me typed gingerly that day -- if whites did not overtly sulk and blacks did not overtly exult – chalk it up to the unspoken understanding that this was only a game, in a time of more momentous events all around us.

Ed Martin

3/15/2016 10:25:23 pm

What George Vecsey is all about in one column. Thanks

George Vecsey

3/16/2016 08:26:46 am

Ed, thanks. It's something I've cared about, from learning from my parents. Best, GV

Thor A. Larsen

3/16/2016 10:04:55 am

George,

George Vecsey

3/17/2016 09:05:56 am

Thor, thanks, certainly playing on the soccer team was a cultural experience -- team had European and American (North, South and Central) roots. (Nowadays, the team representing the four schools within the old building has mostly Caribbean and African guys.) 3/17/2016 06:55:24 am

George and I began an email dialog leading up to the 1999 Women’s World Cup that has developed into a meaningful relationship. I was attracted by his meaningful insight into the people and stories behind the events.

George Vecsey

3/17/2016 09:09:36 am

Alan, I remember listening to Marty Glickman calling the St. John's at Kentucky game, early 50's, Solly Walker first black player to appear on that court, I believe. Lot of tension and Marty, with his own horrible brush with prejudice on the 1936 American track team, put a lot of himself into Solly Walker that night.

Hansen Alexander

3/19/2016 07:09:19 pm

Why George, I remember the game vividly, but our memories are from completely different angles. It was the one time when an athletic game of historical social importance escaped my youthful comprehension. I later covered the Billy Jean King--Bobby Riggs tennis match--from the Astrodome--for college radio--and knew its historic purpose the instant I walked into the joint and heard the hopeful roars of the women that night. But the Kentucky--Texas Western game for me was completely about the short handed Wildcats, that night, as Conley, one of the Kentucky forwards, had the flu or mono, or whatever, and literally played only on defense, making it 4 against 5 when Kentucky had the fall. I can still hear the voice of the late Kaywood Lefwood, on WHAS Radio, Louisville, as the not always consistent sound weaved through the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains, and Dampier passed to Argento in the back court, Riley then a forward doing most of the scoring, Kentucky's big stiff center That Jerez sort of a rebounder, and Conley missing, standing at the other end of the court waiting for Texas Western to come down with the ball. I have no earthly idea why Rupp did not play somebody else at forward, I'm sure there was an explanation that I have long forgotten. I have never heard of a game before or since in which a Coach did that. And you would have thought a national power such as Kentucky would have had a decent bench. I always thought the big racial barrier issue at Kentucky had been in football, where, I vaguely recall, the first black football player was what we used to call "clotheslined" intentionally and paralyzed. I'd have to look it up. I was a Kentucky fan in those days because of Riley, who I had seen in high school. And I kept score of all games I listened to on the radio.

George Vecsey

3/20/2016 08:37:30 am

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MSnLqS2s5s

Hansen Alexander

3/20/2016 02:23:52 pm

Thanks so much George. And of course it is Ledford Floor at the Rupp Arena. 3/23/2016 08:34:53 am

George, wonderful piece! Incredible memory. Extraordinary history. Thank you for reminding (and educating) us all. 3/23/2016 10:48:00 am

There was an impressive list of the post-graduation accomplishments of the Western Texas players. Almost all led constructive lives and many stayed and gave back to their community. 12/21/2016 09:48:28 pm

Great read. It’s interesting to read about people’s road to success. How, if you put in enough work and effort, it will pay off. Definitely motivational. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|