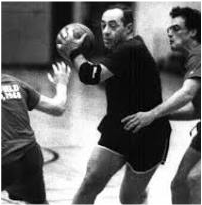

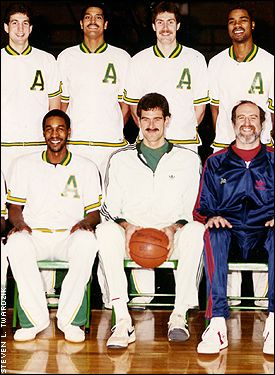

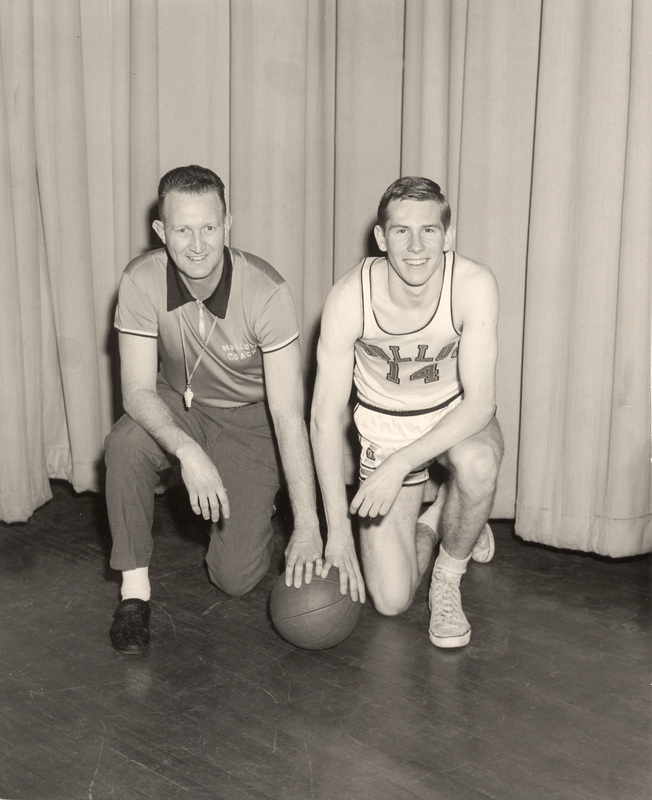

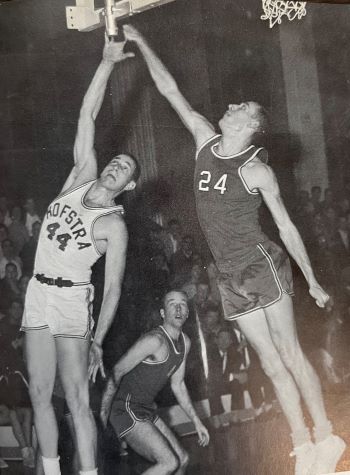

Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, 1960 Hofstra yearbook. Carol Studios. Stan Einbender, Jamaica ’56 and Hofstra ’60, passed on June 10. He had turned 83 on June 1, and had been in failing health for months, lovingly cared for by his wife, Roberta. This is a hard one for me to put together because Stan and I were in the same school for nine straight years -- Halsey Junior High and Jamaica High in Queens, then Hofstra College in Hempstead. Then Stan went to dental school and served as a dentist as a captain in the Army at Fort Lewis, Wash., and settled into his practice in New Hyde Park, marrying Roberta Atkins, helping her with their two children, driving around to dog shows all over the place, in with their English Mastiffs -- a big guy showcasing his big pets. We became much closer in the past two decades, as old Hofstra basketball and baseball guys (and one aging student publicist) got together at Foley’s in NYC. I would drive into the city and back, sometimes with other front-liners, Donald Laux and Ted Jackson. Basketball was our common denominator. Stan had a great souvenir of his season as a 16-year-old senior on the Jamaica varsity -- a scar on his forehead, from the city tournament in the old Madison Square Garden when he was hammered by Tommy Davis of Boys High. When Tommy became a star with the LA Dodgers, I would remind him that an endodontist on Long Island was looking to get him back.  Stanley in 59-60 season. Stanley in 59-60 season. I was at courtside on a sleepy January afternoon in 1960 when Hofstra lost on a long basket by Wagner at the buzzer. It turned out to be the only loss in a wonderful season – 23-and-1, but not good enough to get into a post-season tournament. Half a century later, we caught up with the villain who had beaten Hofstra with that long jump shot – Bob Larsen and a couple of teammates met a few old Hofstra guys at Foley’s, and I wrote about that in the Times., https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/sports/ncaabasketball/52-years-later-recalling-a-shot-that-sank-a-season.html In our old age, basketball was the link. Stanley had two season tickets at the Hofstra gym, right above the scorer’s table, and sometimes he would invite me. He became friendly with the coaches, first with Mo Cassara, then with Joe Mihalich, two basketball lifers who loved our old stories about the memorable coach, Butch van Breda Kolff, the old Knick. (Crude and also insightful, Butch was oddly formal, often calling his players by their full first names—Donald, Curtis, Stanley. As the publicist, I was “Grantland.”) Every October, Joe would invite us to a practice, let us sit behind the basket, give us frank insider critiques of his team. He called Stanley “Doc.” For one afternoon, my guys were part of the team, part of the school, again. I remember at one October practice, the star of the team, a shooting guard at 6-foot-3, also from Queens, was chatting with us, and was politely bemused that Stanley was the star rebounder at the same height. (I wrote about those sweet annual visits to our alma mater.) https://nationalsportsmedia.org/news/my-alma-mater-thrills-some-old-players- Just before the pandemic, Stan stopped getting around, because of Parkinson’s disease and other problems. We would talk on the phone and he would talk about Roberta’s art work and how well she took care of him…and proudly about their family: son, Harry, who had taken over the endodontist practice, (“better hands than me”) and his wife Macha and their children, Max and Remy, and Stan and Roberta's daughter, Margaret Morse, and her husband Richard and their children, Olivia and Henry. He always knew what they were doing. When I visited them last week, Roberta was masterfully managing a hospice operation. (I never heard him complain about his bad breaks with health, and he was always upbeat about the home care from aides like Kenia.) We sat by his hospital bed and we talked about the old days and our dwindling Hofstra guys, and his Yankees and his Rangers….and I praised how inclusive he was about his basketball world. This is what I told him: A decade ago, my wife and I were visiting our friends, Maury Mandel and Ina Selden up in the Berkshires, and Maury’s kid brother Joe and his wife Jean were also there. I suddenly blurted to the younger brother, ”Hey, I know you – from junior high school.” Turned out, Joe had been in the same class as Stanley – and had played on the same class team (Stanley was also on the school team.) I ostentatiously pulled out my cellphone and called Stanley: “I got Joe Mandel here, from Halsey.” They started chatting, more than six decades later, and Stanley told him, “You were a good point guard on our class team.” As any old schoolyard player knows, there is no higher compliment than being praised by a college star. Generous guy, Stanley. Then they started talking about the girls in their class. We continued that conversation the other day -- basketball and girls in our grade -- and for a few minutes, it was very nice to be 13 again. ** (It's so nice to see comments or emails to me, from old friends. Ken Iscol from junior high. Jean White Grenning and Wally Schwartz from Jamaica. A lot of the Foley's gang. Just to drop a few names. Roberta (I knew her brother, Jerry Atkins -- in grade school!) has held things together, admirably. The funeral is Monday at 11:30 AM at Beth David Cemetery, 300 Elmont Rd., Elmont, N.Y. 11003.) For the moment, please feel free to remember Stanley…and say hello to Roberta and the family… here…. They are monitoring the lovely comments here on this site. Thanks. GV “You have no idea what I’m talking about, do you?”

That’s when I started to really like David Stern. It was 1980, and I was just back after a decade in the Real World, now trying to write something scrutable about the finances of pro basketball. I had been referred to David Stern, then the lawyer/financial adviser with the National Basketball Association. After a decade in the Appalachians rather than Madison Square Garden, I remembered the N.B.A. as a haimish mom-and-pop outfit. Now, apparently, the players were making money, which meant the owners were making even more. Stern started giving me a primer on cable television, and why NBA championships were going to be seen in prime time, by millions and millions. I must have given him my usual blank look whenever finances are discussed. (My wife knows that look well.) Stern gave that big but lethal smile and said he would try to make it simple for me. That first meeting set the tone for a long and respectful, if rather sporadic, relationship. Stern, who died on New Year’s Day at 77, is the best sports commissioner I ever covered – making the most impact and lasting 30 years in the job. In addition to his killer-shark business instincts, he also displayed human responses Most sports executives treat reporters like the fools and outsiders we are, but Stern patronized me in a rather respectful way, to let me know I was worthy of a rudimentary education. He was a business maven with the golden touch, who seemed to invent players named Bird and Magic and Michael. Amazing. He also retained at least a feel of the old funky N.B.A. The first league social function I attended – the dinner at an All-Star Game, can’t remember when or where – had its share of business types and current stars but also members of a diverse family: old office fixtures who had worked for the N.B.A. going back to the Maurice Podoloff era, plus several current female basketball players, and a lot of black faces. Two things showed me the human side of David Stern: ---Micheal Ray Richardson had to be banned for life after testing positive once too often. I’ve seen sports leaders grow vindictive, take it personally, when their hired hands let them down, but Stern, talking to a knot of reporters, shook his head at the banishment of the charismatic but hapless star. “This is tragedy,” he said. And I liked him even more. ---One time I wrote a column praising another sports official for taking a stand against prejudice, and on a Sunday morning I got a call at home from Stern praising the column, privately, between us. I was not lulled into misjudging him. I was not totally surprised when Rod Thorn, a star player and long-time insider, hardly a bomb-thrower, disclosed that Stern was acerbic, demanding, around the office. Neither did I think Stern was running a charity. When labor issues arose, he would tell reporters that he was open to any deal that would help both sides. Showing that frightening smile, he would say: “I’m easy. Easy Dave.” Oh, yeah. The league was changing. The N.B.A. opened offices overseas, hired women – women—with language skills and contacts to do-good causes. My friends in the international press, based in New York, started to get credentials for Knicks games because the league had plans beyond the borders. One night, a couple of Italian journalists gave a KOBE 7 soccer jersey of AC Milan to the Lakers’ star, who grew up in Milan. The N.B.A. was not in Sheboygan anymore. (It used to be; you could look it up.) Last example: A couple of decades ago, the New York Times tried to expand its horizons, with a special sports magazine. To attract influential advertisers, the Times held a little dog-and-pony show somewhere in Madison Square Garden, as I recall. A handful of us were to give little talks to the heavy hitters. I gave a rather introverted and whiny talk about how dedicated we journalists were, as if we were humanitarian priests and nuns feeding the poor in El Salvador or something. At the reception afterward, Easy Dave sidled over to me, and with nobody else in earshot he said, “You really don’t get it, do you? These people want to hear about the stars you meet, the games you cover, the places you go. They don’t want to hear shop talk. They want stories. Excitement. Glamor.” As soon as I saw those teeth flashing, I knew he was right. I never had another sports executive criticize me more directly, more privately, more accurately. (Honorable mention: George Young of the football Giants and Fay Vincent of baseball.) I could see why David Stern built the NBA into a world force. I tried to learn something from him. And now I will miss Easy Dave. Sometimes you witness history -- but it looks just like a basketball game.

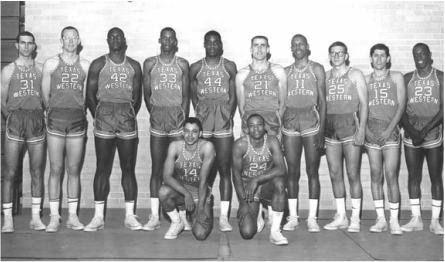

That’s what happened with me, 50 years ago, when I covered the final weekend of the NCAA tournament. Nobody called it March Madness back then. It was merely the semifinals and the finals. The final was between the all-white University of Kentucky team and Texas Western, which usually played seven men, all of them African-American, or Negroes, the name of the time. Everybody knew it was a big deal – nothing like the March on Washington in 1963 or anti-war protests in that tumultuous decade. This was a game, a final. Nobody dug out details to prove it was the first all-white vs. all-black final, although everybody sort of knew it. There was no hubbub on the Web. Actually, there was no Web. Get this: the N.C.A.A. final Saturday afternoon was shown on tape delay that evening. I was there, a young reporter for Newsday, driving down to Florida to cover spring training, and my boss suggested stopping off in Maryland to cover the games. Of all the papers in the land, “we” at Newsday (transient reporters switch their “we” just as ballplayers do) were probably the most socially conscious sports department in the country, writing about race and gender and money and politics. Before the final, our perceptive columnist, Stan Isaacs, wrote of Texas Western: “All of the first seven are Negroes. That shouldn’t be significant one way or another, except that many people make it noteworthy with snickers about the ethnic makeup of the team.” In the University of Maryland field house there was no overt tension – just black players coming out physically, setting a tone. Our professional code said no rooting whatsoever, but I must have been emotionally involved in the game. I come from a liberal New York family that idolized Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson. My dad called home from his newspaper office in 1947 to tell us our Brooklyn Dodgers had officially elevated Jackie Robinson. Yet the stories from opening day hardly mentioned that Robinson was the first black player in the major leagues since the 19th Century. Imagine how that event would be covered today. Fans and reporters watched Texas Western block and defend and rebound, winning the national championship by a 72-65 score. And afterward I wrote that six of the seven Texas Western players were from up north –suggesting they were unafraid, had a point to make. “All seven players who got into Saturday’s final game are Negroes,” I wrote. “They play well together and Kentucky did not seem ready for the way they play.” I watched for details of the upset – handshakes, politeness, all around. Kentucky’s Pat Riley (from upstate New York) and Louie Dampier (from Indianapolis) visited the winners’ locker and congratulated them. I recall how Adolph Rupp, the fabled coach of Kentucky, unpopular with us in New York, exuded respect, chirping that Texas Western was well coached, played hard, deserved to win. Rumor says he raged, used racial words in his own locker room, but Riley, perhaps being loyal to his old coach, has told me that Rupp was sportsmanlike that day. Four years later, I moved to Kentucky as a regional news reporter for The New York Times. By then, Rupp had used black walk-on players; I drove to Lexington to do a story about his first black scholarship player. I remember Rupp’s jovial chirping at me – “How does a feller from New York like our little part of the world?” He had gone with the times, like Bear Bryant and other coaches. (Confession: I became hooked on UK from living there; when Duke’s Christian Laettner took his killer shot in 1992, I instinctively jerked my head in blatant body English, to no avail.) Over 50 years, Texas Western-UK has come to have epic meaning. (The winning school is now named University of Texas, El Paso.) Thirty years after the game, I wrote a reprise for The Times. Recently, the surviving players have been talking about it leading up to the actual anniversary on March 19. So much has come from that low-key day in Maryland in 1966 – players like Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Michael Jordan, coaches like John Thompson and Nolan Richardson, maybe even a cool former Harvard Law Review president with his lefty moves on the White House court. If reporters like me typed gingerly that day -- if whites did not overtly sulk and blacks did not overtly exult – chalk it up to the unspoken understanding that this was only a game, in a time of more momentous events all around us. Ted Cruz, the lawyer who scorns election ambiguities and disclosure rules, also scorns “New York values.”

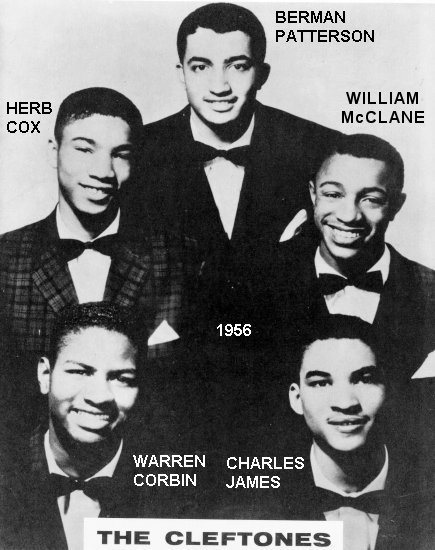

We know what Cruz is doing – going after the evangelical vote by raising that old specter, the urban type, with noses and accents and odd names and weird food tastes. You know. The city where America’s children go if they think they can make it there. Cruz was going after Donald Trump – and welcome to that – by making him typical of New York. But as somebody who grew up a crucial half mile from the Trumps, I have to admit, the Donald, in his own vulgar way, represents a sub-group, his home borough of Queens. Simon & Garfunkel. 50 Cent. My Jamaica High chorus members, The Cleftones, who played PAL basketball for the 103rd Precinct. Bernadette Peters. And I remember my friend’s older sister, when I was 10 or so, raving about “that Tony Benedetto from Astoria”. The man is still singing, but now to Lady Gaga. Many of us from Queens form a yappy lot. Is it the vital separation from “The City” – Manhattan? Looie Carnesecca, for many years from Jamaica Estates, says New York pizza is the best because of the water. Is it the brackish water of Flushing Bay and Jamaica Bay and Newtown Creek that makes Queens people tend to mouth off? Or is it the relative space and light that grows characters? John McEnroe. Jimmy Breslin. Howard Stern. Fran Drescher. Christopher Walken. Trump is a mouthy rich boy, but Cruz prodded him into the first dignified moment of his campaign, maybe of his life. Trump stuck up for us, the people with the New York values. Athletes? The common ingredient of Queens jocks is the need to handle the ball. Point guards. Control freaks. Bob Cousy-Dick McGuire-Kenny Anderson-Kenny Smith- Mark Jackson-Nancy Lieberman, who took the A train from Far Rockaway to Harlem to get a game. Peter Vecsey, who played for Molloy and writes about hoopsters. And from Jamaica High and St. John’s, Alan Seiden, known in the P.S. 26 schoolyard as “And One,” because he called a foul every time he took a shot. Bob Beamon, from Jamaica High, was a dunker, not a passer. He could leap. Leaped to a world long jump record in Mexico in 1968. The thing about Queens is that the subway and elevated lines all head west, toward The City. I remember slouching in class at JHS 157 in Rego Park, watching the No. 7 El rumble toward The City. Trump lived a few blocks from the last stop on the F Line but I wouldn’t bet he ever took the train. Probably got chauffeured to his prep schools. With all this glorious diversity around him, somewhere along the line Trump developed outsize prejudices. This tells me he never spent much time with Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard. He would have a different facial look if he had. Queens College graduates: Jerry Seinfeld. Ray Romano. Howie Rose, Mets voice. Cruz is playing to the base, the red-hots who cheered him in South Carolina and might caucus for him in Iowa on Feb. 1. His code words of “New York values” are an insult to the Chinese in Flushing and the Koreans along Northern Blvd. and the Latinos around 82nd St. and the South Asians around 74th St. -- and my friend Alton Gibson from South Jamaica who disregarded his guidance counselor’s advice to take vocational classes, and got himself advanced degrees and a good career. Those New York values. Mario Cuomo from South Jamaica who married the beautiful Matilda Raffa and led a life of good works and talented children. In Queens, we talk and write and sing and dream. Letty Cottin Pogrebin. Stephen Jay Gould. Stephen Dunn, zone-busting guard and Pulitzer Prize winning poet. Francis Ford Coppola. Sam Toperoff. Lucy Liu. Russell Simmons. Idina Menzel. Michael Landon. Cyndi Lauper. Joe Austin, Mario Cuomo’s coach for life. The bright young woman from the English class in Jamaica High a decade ago, now a college graduate doing advance work for Bernie Sanders in New Hampshire. The bright young woman from two decades ago, now getting her teaching certificate in the grand building on the hill. Those voices Those accents. The great spices emanating from open doors and adjacent apartments in Astoria and Bayside and Hollis and Ozone Park. The dreams. The drives. The New York values. A former college basketball star I know sees way too much of the New York Knicks and Philadelphia 76ers.

An intense player and demanding coach once upon a time, my friend has the distinct feeling he is observing a crime being committed. We both knew players, decades ago, who dumped games, shaved points, to satisfy gamblers on one side of the point spread. Some (not all, I suspect) got caught. Many had their lives ruined; a few went to jail. That is not the problem with the 76ers and Knicks, whose cumulative record was a ghastly 10 victories and 63 losses, as of Friday morning. The players are doing their earnest best to win but the owners are doing their dishonest best to keep the talent level down, in order to choose a top star in next spring’s college draft. It enrages my competitive friend to see teams in the National Basketball Association skimping on salaries. He calls me and rails: What is the ethical difference between NBA teams ironically dumping games in plain sight by “virtue” of dumping salaries and the old point shaving by players? My outraged hoopster friend asks if some of the executives’ activities are not some kind of crime, or at least a significant breach of competitive integrity? Why do the NBA poobahs allow such a public breach of faith with its fan base, the ultimate victims. Are the poobahs’ eyes shut to this “gaming of the system?” I wonder if there is not some eager prosecuting attorney out there who could investigate the business tactic of tanking an entire season. And what about the wealthy patrons who pay outrageous prices for seats and so-called food in Madison Square Garden? These folks did not accumulate their riches by being pushovers in their business lives. Is there not a potential class-action suit festering among the expensive suits at courtside? Adam Silver, the still-new commissioner of the NBA, may be preoccupied by his announced goal of allowing gambling on his sport. Gambling used to be considered a vice. Now it is a way of raising money because people don’t like paying taxes for roads and bridges. Meanwhile, Silver has part of his league playing with inferior rosters in an attempt to reload, cover up past personnel mistakes, and take advantage of a system that is anti-competitive. My friend used to dive for loose balls and rage against indifference. Now he sits in front of the tube and watches the Knicks and 76ers stagger around, according to the schemes of their ownerships. I know of a former college player who got caught taking a few dollars to shave a few games. He’s never re-connected with teammates who would love to see him. He lives a clean life, after what he did. But the owners of NBA clubs sit in the front row and smirk. Shouldn’t there be laws against owners blatantly trying not to win? Whether it’s the owners or the players, dumping a game or a season emits the same foul odor. For a public figure compared to Hamlet or some of the major saints, Mario Cuomo had a fiendish side.

I once reminded him the way basketball players of St. Monica’s parish in South Jamaica, Queens, used to take advantage of two tile pillars smack in the middle of the court. While Sunday Mass was being held on the main floor, the Leprechauns or the Shannons would usher in new victims to the basement. Joe Austin, Cuomo’s coach for life, taught his players to run the old pick-and-roll play on the valid theory that a tile pillar cannot be whistled for setting a moving pick. When Cuomo was governor – a huge source of pride for those of us who grew up around Jamaica – I reminded him how unsuspecting visitors got our brains bashed in. His laugh was long and villainous, from deep in the chest, as he mirthfully remembered suckers decked out on the floor of the rec hall. That was fun, he said. The man had articulate empathy for the poor, the marginal, of his home state, of his nation, of the entire world, but strangers in the basement of St. Monica’s – tough luck, man. From what I heard, he carried this rugged ethic to the basketball games in Albany during his long tenure as governor. In 1993, he told Kevin Sack of the Times: “I'm the most formidable figure on the court because I own the league.” He added, “They all work for me and I am notoriously ungrateful to people who make me look bad.” He was proud of being a jock, a minor-league outfielder until he was beaned in the pre-helmet days. He reveled in the ringer names he used in the amateur leagues -- Glendie LaDuke or Matt Denty or Lava Labretta (because he was ''always hot,” the governor of New York once told me. Cuomo had a long memory, good and bad. For his inaugurations, he invited his gremlin mentor, Joe Austin, who ran a great baseball program on the field of Jamaica High School, when he wasn’t working the night shift at the Piels brewery. Cuomo would address remarks to “Coach,” and when Austin passed, Cuomo made sure that a street and park near the old Jamaica field were named for him. We had a minor connection to the Cuomos – somebody in our extended family became a friend of theirs when the family moved into the twisting back streets of Holliswood. Matilda Cuomo visited our house once, a lovely lady, and my parents voted at the same hall as the Cuomos. The governor spoke well of our relative -- even when she became a hard-core Palinite. He was a beacon to those of us who learned our lessons well in central Queens – that Jamaica Estates and Hillcrest are inextricably linked to South Jamaica and Hollis, that we are in this together. He brokered a housing agreement in Forest Hills when it seemed impossible. Maybe reason and compassion would work elsewhere. In July of 1984, my wife and I were sitting in an outdoor restaurant in Santa Barbara, listening to a couple of stockbroker types at the next table discussing the Democratic convention up the coast, where Mario Cuomo had delivered his epic speech. The two money guys told each other that Reagan would sweep the 1984 election, but that Cuomo was now the favorite for 1988. And they were Republicans. It never happened. Mario and Matilda Cuomo remained New Yorkers, perhaps a regional taste. He had wielded his elbows on the court, and maybe that kept him from needing to wield his elbows for the presidency. Don’t give up.

Don’t despair. This is the lesson of Phil Jackson, who now returns to rescue the Knicks, indeed, rescue New York. I remember the night – the late night – in February of 1985, in a Mexican joint in Florida, when he lamented that he was done, finished, in the National Basketball Association. I’m a bit older than Jackson, can remember him coming along in the late Sixties, a thoroughly likable counter-culture guy from the Upper Midwest, who went with Bill Bradley to Allard Lowenstein anti-war rallies. The Knicks had virtually a whole team of cool guys. It was a great time to be around them, and not just because they eventually won two championships. However, by 1985, Jackson had convinced himself that he would never work in the N.B.A. again. His playing career was over, and he and Charles Rosen had written his book called, “Maverick: More Than a Game,” that revealed just where Jackson’s shaggy head was at – perhaps not a good idea in the N.B.A. job market. I was in spring training with the Mets in funky old St. Petersburg, and Jackson and his Woodstock buddy Rosen – once the star at Hunter College -- were coaching the Albany Patroons of the Continental Basketball Association, a league of bizarre travel connections to places as distant as Puerto Rico and Oshkosh, Wis. We went out for pizza after a game, along with Herbie Brown, who had coached the Israel Sabras, Detroit Pistons and Tucson Gunners, and they were telling horror stories about overnight drives and changes-in-Atlanta. Phil Jackson was morose. It was late at night, and he was morose. He was done. Cooked. His modest revelations into life style and politics had revealed himself to be a liberal, perhaps a troublemaker by Reagan-era standards. The N.B.A. was flush, with Erving and Kareem going out, Bird and Magic and Jordan in their prime. In Jackson’s fevered mind, there was no room for a perceived hippie. My role was to order the food and the beer and scribble down travel tales while his colleagues tried to talk Jackson off the conversational ledge. Have another nacho, Phil. Change planes in Atlanta a few more times. See what happens. It’s just a box of rain. I don’t believe anybody said that, but you never know. Next time I saw Jackson was in the Garden. He was an assistant coach with the Bulls, wearing a suit and a surprised look. The thing I remember most about his Jordan years was that he loved annoying Pat Riley and all the other Knick coaches and suits, but he moderated his antagonism out of respect to Red Holzman, his coaching godfather who was always at the games. Now Jackson has won 11 championships, not bad for a perceived anarchist. He has enough stature to force James L. Dolan to downgrade the absolute weakest link of the New York Knicks franchise, that is to say, James L. Dolan himself. The hippie as corporate savior. I wonder if Phil remembers that night in the Mexican joint. * * * My travel column from 1985: http://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/21/sports/sports-of-the-times-on-the-road-to-oshkosh-again.html I caught up with Charley Rosen in 1997, by which time he and Phil were pursuing separate muses: http://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/11/sports/novelist-and-a-coach-are-still-hanging-out.html Filip Bondy on Jackson the other day: http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/basketball/knicks/bondy-yipee-hippie-garden-exec-phil-long-bohemian-roots-article-1.1723057 The aggressive swarm of Seattle Seahawks reminded me of a young HC of the NYJ.

Not Bill Belichick, but Pete Carroll. Carroll was the new head coach in 1994. He had an outdoor basket put up in the Jets’ bunker, on the theory that team members might enjoy shooting hoops in their spare time. Some football people snickered at this unorthodox maybe-Left-Coast way of doing things. The Jets went 6-10 and Carroll was fired by the owner, Leon Hess, the oil man who used to tell a Times reporter to please not write that Hess had visited Jets’ camp because he was supposed to be in the office. Carroll later coached the Patriots and won a national title at Southern California, where he ran around at night with youth gangs, urging members not to tear up their world. Now the Seahawks have humbled the Broncos, showing not only speed and power but also the flexibility to make big plays. They could react, not just follow orders. I thought about the outdoor basket at the Jets’ bunker, and the new coach who had a somewhat different way of doing things. * * * There was another moral to the Super Bowl. The NFL tempted fate by putting a Super Bowl in a northern clime, in what is turning out to be a nasty winter. Some gloom-and-doom types, no names mentioned, forecast a blizzard. But the Giants built pro football in New York by selling a few hundred extra tickets on Sunday mornings when rain or snow or chill somehow dissipated and people felt like going out to watch a game. In New York, this glorious tradition is known as Mara Weather, after the family that still owns half the team. The Super Bowl was played on an early November or early April day. Mara Weather. Never, ever, forget it. Somebody said Jack Curran should have been a priest, and somebody else said, he was.

This old-fashioned man, who coached basketball and baseball, and lived his faith, passed on Thursday at 82. The obits all said he never married, that he passed up college coaching jobs so he could take care of his mother, and how he pitched batting practice for Molloy into his late ‘70’s. “How’s your arm?” I would ask when I called for some old-fashioned city wisdom. “Not bad,” he would say. He blew out the arm in the minor leagues, which pushed him into coaching two sports for nearly six decades. A few hours after Curran passed, I received an email from a reader I did not know. Write something about Coach, it asked. Of course, I did not need to write a word. Three of my favorite writers at the Times have captured him perfectly: Vincent Mallozzi on Curran’s 50th anniversary: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/08/sports/ncaabasketball/08curran.html Dan Barry: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/10/nyregion/father-basketball-long-into-overtime-after-45-years-coach-still-teaches-layups.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm And Bruce Weber, in the obituary: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/15/sports/jack-curran-a-mentor-in-two-sports-dies-at-82.html?_r=0 So nobody needs me. But as a son of the city, I can remember him as a scrawny, big-eared red-headed sub with the good St. John’s basketball teams, intense, observant. I can remember my brother Peter, later a landmark basketball columnist in this town, playing both sports for Curran. As a younger reporter, I thought Curran was a bit single-minded, and probably so did his players. The older we got, the wiser he became. Funny how that works. In recent years, I went to Curran for wisdom, for opinion, for honesty. He knew what he knew. When area baseball coaches went along with the aluminum-bat lobby, Curran put together anecdotal impressions of youngsters being skulled by line drives that never should have traveled that fast. He lobbied his school to vote against the bats. It was the right thing to do, and he did it. This is what I wrote: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/14/sports/baseball/14vecsey.html He was proud of graduates like Jim Larranaga who went on to coach George Mason in the Final Four: http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9403E7D71530F933A05750C0A9609C8B63 I must add, he agitated for every break, the way the John Woodens and Dean Smiths did. A friend who played for a Queens public school recalled how annoying Curran could be, pestering the refs and the umpires. But his players were well-taught, my friend added, and they were tough. Dan Barry noted the yin/yang of Jack Curran’s quotidian life, Mass, commuting across the bridge, coaching everybody, even kids on the opposing bench. Barry wrote how Curran balanced “his daily aggressive commands – ‘Box out!’ -- with that saying of St. Francis of Assisi he carries: ‘Preach the Gospel every day and when necessary, use words.’” Jack Curran kept that saying folded in his wallet. When people compared him to a priest, even in these complicated times, it was meant as an old-fashioned compliment. Comments about Jack Curran are welcome here. The scariest thing I ever saw on a basketball court was the maniacal grin of Art Heyman, 10 feet above the floor, as he wielded a pair of scissors.

He was cutting his segment of the net after Oceanside High won the 1959 Nassau County tournament; I stopped taking notes to make sure he got down off the ladder without inadvertently doing harm to anybody, in his zeal. Life was always an adventure with Heyman, during a game or during conversation. You never knew wherethings were going. Artie died two weeks ago at the age of 71 in Florida. He would come and go in life, as he did in his mercurial pro basketball career, which consisted of six seasons, two leagues, and eight hitches with seven different teams, plus a few paper transactions with teams that decided they could not use him. He had so much talent coming along as a big-beamed 6-foot, 5-inch star at Oceanside and Duke that it was reasonable to envision him as the next big thing to Oscar Robertson. In fact, the award he won as the best college player of 1962-63 is now called the Oscar Robertson Trophy. Heyman must have had Robertson on the brain. When he was at Duke he used to take little sojourns to the Carolina coast, bringing along a lady friend and registering as Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Robertson. Once he was arrested because the girl was under 18. He was not without his flaws, which he knew as well as anybody. I found him interesting but then again I didn’t have to coach him, as Frank Januszewski did at Oceanside or Vic Bubas did at Duke. He could taunt opponents, take a punch at somebody for no reason, and toss elbows in practice, just out of meanness. He was big enough to insinuate himself toward the basket, like Robertson, and when the Knicks drafted him first in 1963-64, he scored an average of 13.4 points in 75 games – what turned out to be the best season of his career. The next year he was sitting a lot after Harry Gallatin, the rugged old forward, was brought back from the Midwest to coach the new breed. This really happened: I was with the Knicks in a hotel lobby in Providence, when one of the players, rolling his eyes, informed us that crazy Artie had been playing poker after a loss to the Celtics earlier in the night, and Gallatin walked by the open door and, in a gesture of friendship, asked if he could take part. “If you won’t let me into your game, Coach, I won’t let you into mine,” Artie said, and meant it. The next season he was at Cincinnati, and after that he was in the American Basketball Association. He had a bad back; the attitude was not so good, either. One year Heyman was playing for the New Jersey Americans, the forerunners of the new Brooklyn Nets. That is to say, before the Nets had Julius Erving from Roosevelt, L.I., they had Artie Heyman from Oceanside, L.I., a few miles away. After games Artie would beat it back across the George Washington Bridge to the East Side of Manhattan, where he ran a bar that catered to flight attendants and males. His career in the singles-bar trade was as disjointed as his basketball career or his persona. It was hard to keep things straight with him. I would diagnose him as having concentration issues; there was something sad about him, an inner lost child. I ran into him in Manhattan in his various bar cycles, would catch up on the phone when I could track down his number. About 15 years ago I ran into him in North Carolina. He did not look healthy, and he felt under-appreciated. It was a long way from Oceanside High, when he climbed that ladder with the sharp object in his hand and nobody dared turn away. With deep gratitude for all the fun last winter, my best wish for Jeremy Lin is that the Knicks will somehow decline to match the sumptuous contract from Houston.

Lin cannot play to his potential with the Knicks, who are now a two-man team – Carmelo Anthony and James Dolan. Anthony has been empowered by ownership to call for the ball and make his solitary moves toward the basket. Anthony is is a one-dimensional player with no concept of team motion. In their short time together, he displayed open scorn for Lin’s style of finding the holes and dishing to the open man. It was Anthony's team, Anthony's ball. Jason Kidd is old enough and wise enough to adjust to Anthony’s self-centeredness. Otherwise, he would not have signed on. But Lin needs to find his rhythm for a full season in the N.B.A. with teammates who will play with him. That won’t happen with the Knicks. As Howard Beck points out in his expert analysis in Saturday’s Times, the Knicks must respond to an offer sheet of $19.3-million for three years for Lin, as soon as next Wednesday. They have reason to wonder if he can become the point guard of the future. Lin should have equal skepticism about whether he can succeed with the ball disappearing into the Bermuda Triangle that is Carmelo Anthony. With any luck, Lin fakes to New York and takes a quick step to Houston. Wat Misaka did me the honor of calling back Monday night and giving his viewpoint on Jeremy Lin.

We haven't seen each other since the summer of 2009, when he saw his name on a 1947-48 team plaque outside the Knicks' locker room. Misaka's comments are up and running on the NY Times site.On Tuesday night, Lin hit a 3-pointer in the final second for a 90-87 victory. I just looked it up: because of the strike, the Knicks don't play in Utah in this short season. Wat Misaka is going to have to do his rooting via the tube. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/15/sports/basketball/knicks-pioneer-roots-for-the-underdog-in-lin-george-vecsey.html?ref=sports By now, I can envision videos of Jeremy Lin’s amazing adventure of the past two weeks being downloaded from the United States to China in a new form of cultural exchange.

Lin is the Chinese-American basketball point guard from Palo Alto and Harvard who has scored 20 points in five straight games after nearly being cut from this erratic franchise. His foray against the Lakers and other teams would do wonders for the self-image of home-grown Chinese professionals, who do not believe they have the psyche or the soma to compete against Americans, even the discarded Yanks who wash up in the Chinese league. This confession of inadequacy is one of the many powerful points of one of the best books I have read about contemporary China – Brave Dragons: A Chinese Basketball Team, an American Coach, and Two Cultures Clashing by Jim Yardley, just published by Knopf. Confession: I know and admire Yardley, a colleague from The New York Times, formerly posted in Beijing, now in New Delhi. In 2008, Yardley caught up with Bob Weiss, a lifer player and coach in the National Basketball Association who, on a bucket-list kind of whim, had accepted a job coaching the pro team in Shanxi, a marginal team in the coal region of China. As it happens, Weiss wound up working with a Steinbrennerian character named Boss Wang, who treated him the way the American Boss used to treat Billy Martin – you’re up, you’re down, you’re in, you’re out. Weiss’ patience and curiosity kept him in this grim city, working for a tyrant, and opened up space and time for Yardley to meet itinerant Nigerian, Taiwanese, American, Kazakh and Chinese hoopsters. Eventually, the Chinese professionals grew to trust the Mandarin-comfortable Yardley, providing insights into their souls. “As we all know, Asian players are not as capable as players elsewhere.” This was the sentiment not of an outsider but of Liu Tie, a lanky former player who was often ordered by Boss Wang to coach the Brave Dragons instead of Weiss. Liu’s volunteered observation stunned Yardley, who writes that their dialogue “would run roughshod over political correctness parameters in the United States.” But Liu stuck to his beliefs: “We know we Chinese players are different than African American players. They are more physically gifted. We are not. But we believe that by working harder, bit by bit, it’s like water dripping into a cup. Over time, you finally achieve a full cup.” Many of the Chinese players exhibit deference when they see the skills of Donta Smith or Bonzi Wells, two Yanks who pass through, and they watch the admirable work habits of Olumide Oyedeji, a selfless Nigerian center who has passed through the N.B.A. But what they lack, just about everybody agrees, is the individualistic gall to “take it to the rack and stick it,” in the immortal words of Benny Anders, circa 1984, once a promising flash with the University of Houston. Since the international “take-it-to-the-rack” gap is freely admitted by Chinese pro players in Yardley’s book, the solution would seem to be a communal viewing of the recent rampages by their soul brother from California. Lin has played with schoolyard abandon and Ivy League intelligence in reviving a Knicks team that was going nowhere with its solipsistic superstars, Anthony and Stoudemire. So the question for the Knicks now is not how Lin is going to co-adjust with them, but rather how they are going to co-adjust to him. Lin has been penetrating on the best in the game, like Kobe Bryant and Pau Gasol of the Lakers, and if they shut him down, he kicks the ball to somebody else. This discipline is unheard of these days, in an age of N.B.A. players “who shoot when they should pass and pass when they should shoot,” in the caustic words of former Knick coach, Jeff Van Gundy. The fault is not in the genes or the hearts of the Chinese players; their coaches and bosses need to let the game evolve beyond ideology, into art with a purpose. On every level, Yardley’s book is a treat. Like so many of the best recent books on China, he takes us places we are not likely to be going, even as tourists. He takes us to the gyms and arenas as well as the hotels and restaurants and train stations of modern China. He lets us see China through the eyes of not-at-all-ugly Americans like Bob and Tracy Weiss, as they explore a new land. Yardley has the same empathy for Chinese working people as he does for an itinerant player from Kentucky or a failing point guard from Taiwan. For years I have thought that the ultimate book on Chinese basketball was Operation Yao Ming The Chinese Sports Empire, American Big Business, and the Making of an NBA Superstar, by my friend Brook Larmer, published by Gotham Books in 2005. Now it’s a tie. To prepare for covering the Olympics in Beijing in 2008, I read a dozen terrific books, including China Wakes: The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power by Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, Random House, 1995; River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze, by Peter Hessler, HarperCollins, 2001; and Oracle Bones, A Journey Between China’s Past and Present, by Peter Hessler, by HarperCollins in 2006. Yardley’s book on the Brave Dragons joins them. And the commerce goes both ways – Jeremy Lin videos are surely winging their way electronically to China, to show the next generation: dudes, you can do this. |

Categories

All

|