|

(My late-in-life friend shares his mission to be sober, one day at a time. We speak the same language, because I gained so much from helping Bob Welch, the late baseball player, write a book about his sobriety. This email popped up on my screen over the weekend.)

(From my friend:) Blessed to share that today is my 34th Anniversary of Sobriety. (12/3/89) Amazing. Some of the gifts that keep on giving......

Dessert Saturday Night, the special Gelato; vanilla with blueberries and strawberries........a sugar, cinnamon topping. I took one spoonful, put my spoon down. Called the waitress over and asked, is there any liquor in this dessert. "Oh yes, the berries are soaked in rum." I told her she could take it back, I cannot eat that. Funny, it was called 'Fire and Ice'.........the fire was, in their understanding, the sugar-cinnamon topping was flamed a bit. Well, the fire here? The rum. I knew it right away. She gave me a different one, Apple Crumb!! I made it disappear. The lesson? I need to continue to be vigilant. Too much to lose. No guarantees. Continuing to be a student of this disease, the darn diploma hasn't shown up yet, so I keep learning. I saw that movie, “Maestro,” some of Leonard Bernstein's life, the ups and downs. He had a number of things I can identify with, and being honest, I was reminded of the wild scenes he mixed into. High performer, heavy partying. I might not be a maestro, I was the other. I could write more, but made the point to myself and you, some who knew me then and now. Some who share sobriety. All of you, the group of quality people I am a winner with. I like winning. On to another 24 hours of this life. Thanks for listening. One Day at A Time. ### (From GV) (This mentality works. I was indoctrinated by Bob Welch, the year after he became sober, after nearly blowing up a promising pitching career with the LA Dodgers. Bob had become a true believer, even when he had a bad day. I will never forget the day the Dodgers were eliminated from the playoffs by the St. Louis Cardinals, and I popped into the Dodger clubhouse as part of my columnist job. The Dodger clubhouse was nearly empty, and Bob explained: “A lot of the guys are out in the back getting hammered – but I choose not to.” By that time, I had inculcated Bob’s attitude. I almost never drink. Don’t need it. I had an earlier example: A family friend, Mary from Ireland, was one of the first women to be active in Alcoholics Anonymous. She made people think about addiction. So when my New York friend drops a reference to sobriety into one of our emails, or in person, we are speaking the same language. Thanks for the note, man.) Just in time for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day comes the ickiest New York Times series I have ever seen -- not that the Times’ coverage by the great reporter Nicholas Confessore and colleagues is icky but because the subject matter is so icky.

The Times ran a tree-part series about Tucker Carlson, the angry widdle man who apparently is bigger than O’Reilly, bigger than Limbaugh, bigger than Hannity. And in the very same Sunday issue was a Review article about J.D. Vance, the Yale-Law-School money-man who became famous for criticizing Appalachian people without pointing out the corporate and political causes (I’m talkin’ about you, Commodore Manchin.) Vance is now, goodness gracious, running for the Senate from Ohio. And in the Monday Times is a column by Michelle Cotttle pointing out that the hottest campaigner in Ohio – better teeth, slimmer figure, more elephant-part trophies – is Donald Trump, Jr., not the doughy, grumpy-looking J.D. Vance. Yuk. What do these three worthies have in common? The answer came to me: dysfunction, broken sons lashing out at the world without a tangible speck of compassion or solution. The political party that once boasted of family values is now being represented by angry boys left adrift by parents. According to the Times’s reporting, Carlson was abandoned by his mother, whose dissolute ways led her to Europe, leaving him to claim at an early age that this had nothing to do with him. The evidence is that young Tucker drank and groused his way through his teens and into his 20s, and when he found a persona it was a critic of the left. According to the Times, Vance’ mother had the same weakness now raging through the strip--mined, job-bereft, opioid-glutted region whose sons and daughters have migrated northward into Ohio. (I spent many years writing from Appalachia and its extensions, and wrote two books about the region, and feel great bonds with the many good parts as well as the bad.) The Times reports that Vance’s mother has been clean for seven years. God bless her. When does he go to work on his own bravado and anger? If he is running for the Senate, when does he grow a bit of compassion? The third member of the testy trio is young Trump, who apparently gets more attention than Vance out on the trail. He apparently stumbled around during college, and had several blocks of time in his youth when he did not speak to his father, who was giving the world a critique of his latest hottie, and making a habit of putting his hands on women. As it happened, I had a few glimpses of the Trump ménage before the frightening White House years. (We grew up half a mile and seven years apart; his late brother Freddie was a nice guy. We have since sampled Donald Trump’s emulation of his crooked-dandy father, his disdain for his homebody mother.) When I came back to Sports in the early 80s, Trump owned a low-rent football team in New Jersey called the Generals. He knew nothing about his team – the coach, the players, the rules – which he would prove at occasional press opportunities in his gilded hotel lobbies. His alarming inability to focus on details was pointed out by his blonde wife Ivana sitting next to him, and interjecting, in her lush Czech accent “No, Donald, Walt Michaels is the coach, not the general manager.” Ivana would patronizingly correct Trump about this and that, and at some point they were divorced. Whatever the three children really felt, if anything, they eventually knew which side to take, which has led them to today. So now one child of dysfunction campaigns for another child of dysfunction while a third child of dysfunction yammers at immigrants and minorities and liberals. What a trinity, so filled with pain and anger, passed on by an earlier generation. As Mother’s Day and Father’s Day approach, it is time to give thanks for parents who stuck it out, who were a presence, who tried, who disciplined when they could, who gave, who loved, in their ways. (Mom and Pop, I never thanked you enough. You were always on our sides.) It is human to feel compassion for these three broken men, whose pain is on such public display. May they process their rage, may they learn to do less damage. May they heal. But more important, may this country heal, somehow. Maybe it’s the pandemic, but people seem to be forgetting the dangers of alcohol and gambling.

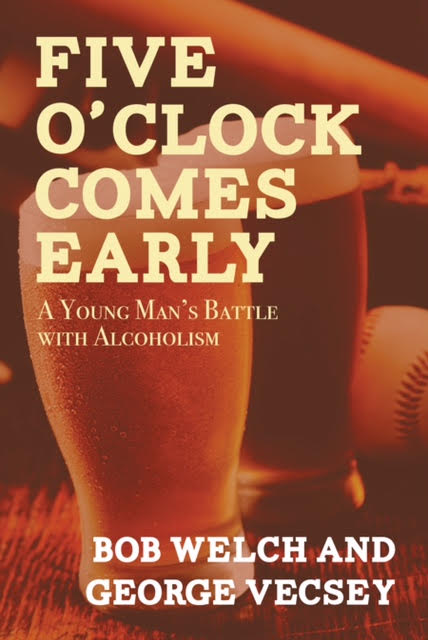

I base this on the recent approval of gambling outlets in New York State plus the avalanche of gambling advertisements on baseball broadcasts in the reign of Commissioner Rob Manfred. Um, does the name Pete Rose strike a familiar chord? Last I looked, that sick puppy is still banned for doing what the alluring TV ads urge people to do – bet the rent or the grocery budget on the wayward bounce of a baseball with Rob Manfred's signature on it., And the dangers of alcoholism seem to be minimized by a new movie directed (not produced, as I originally wrote) by, of all people, George Clooney, for whom I have high respect. Clooney has sent forward a movie, “The Tender Bar,” adapted from a fine book by J.R. Moehringer about his exposure to alcohol as a very young man, admiring his bartender uncle and missing his absentee father, leading to his eventual admission of powerlessness toward alcohol as an endangered adult. “The Tender Bar” movie is being hawked every couple of paragraphs on my incoming Web glut. I get the point. Little kid, hanging out in a pub, gets pulled into the life. I was tempted to push the button to watch the movie on my laptop, but then I read two rather different reviews of the movie in The New York Times. Critic A.O. Scott suggested the movie is lightweight, skipping from episode to episode: “Ít’s a generous pour and a mellow buzz.” But free-lance critic Chris Vognar takes a more critical look at the dangerous slide of a young man, made clear in the original book. Vognar writes: “…for a film with the word ‘bar’ in its title, it contains remarkably little insight about alcohol, where it’s consumed, and what it does.” The two critics talked me out of watching. Why, you ask, do I take gambling and drinking so seriously? I’ve seen gambling up close and have great respect for people who seek out Gamblers Anonymous and reinforce themselves, regularly. I have also seen alcoholism up close, having helped Bob Welch write his book, “Five O’Clock Comes Early,” about how he was having blackouts in his early 20s, jeopardizing his pitching career with the Los Angeles Dodgers, to say nothing of his life. By the time I signed on for his book, Bob was already sober from a hard month at a rehab center, and he was an advocate of daily reminders to stay sober. I later spent a family week at the center, and took a great deal from the process, from seeing endangered lives be turned around. Bob knew the dangers, and he verbalized them – part of the process. “I choose to be sober today.” As far as I know, he stayed sober for the rest of his life, which ended tragically young, 57, from an accident. Now I have a close friend who reminds himself daily how he, and Alcoholics Anonymous, saved his life. Why do these reviews of “The Tender Bar” strike close to home? As it happens, I live close to Moehringer’s home town, and have spent too many long minutes waiting for a red light to change, staring into the silhouettes in Moehringer’s pub. Plus, I have known several relatives of Moehringer, and have been apprised that he was not exaggerating his childhood. His book was great; I’ll skip the movie. Now, back to gambling. We all know how much money is gambled on sports, every day, everywhere. (The first college game I ever saw in the old Madison Square Garden was a dump, Kentucky stunningly losing to Loyola of Chicago.) I consider “Eight Men Out,” about the Chicago White Sox players who dumped the 1919 World Series, to be the best sports movie I know. Gambling did not go away when Pete Rose got busted for betting on baseball, including games in which he participated as manager (and, I am sure, as player.) I remember how the late baseball commissioner, Bart Giamatti, adamantly criticized all gambling --- including government-run lotteries. For Major League Baseball to permit gambling ads is dangerous; for New York State to permit gambling sites is also dangerous. (For that matter, I see that The New York Times, that great newspaper, is spending a ton of money to acquire a website, “The Athletic,” that is heavy into gambling odds. How does that impact the parent company when gamblers make or lose money via odds listed in that outlet?) We have a social brain fog that accepts drinking as a mellow haze that can be controlled, that encourages people to bet on capricious games. Then again, we see dopes like Novak Djokovic and Kyrie Irving and Aaron Rodgers misleading and blustering about vaccinations. Plus, an entire political party is going along with thugs invading the Capitol. Can we blame the pandemic for all this? Much has been made – deservedly – about what Don Newcombe accomplished on the field but much less has been written about how he saved lives.

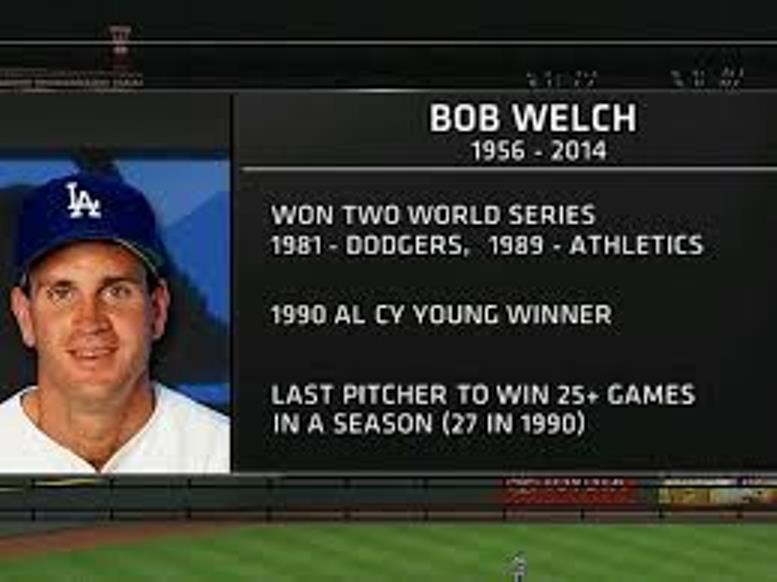

Newcombe, who died this week at 92, put himself out there, as the rugged face of beating back addiction, day by day. He was one of the first public figures to talk about addiction – before Betty Ford, before other prominent people. Newk was at his most formidable around the Los Angeles Dodgers, his old team. He was the Dodgers’ “director of community relations,” which meant he spoke about race and addiction and good citizenship, offering himself as a prime example, how he had wrecked his career as a pitcher (and pinch-hitter deluxe), by drinking. He gave testimony of how he had gone sober, on his knees, promising his wife he would never drink again. The amazing thing about this tough guy is that he did it by himself – just stopped. Most alcoholics rely on daily reinforcement, the meetings, the written word, the prayer to a higher power. Newk just stopped. This guy was so tough, he would not take gas or injections at the dentist, to deaden the pain. He never went to a rehab center, never went to AA meetings for himself, but he did not recommend that path for anybody else. He told other people that rehab worked, and that they should seek it, and sometimes he accompanied them right into the center. He also stalked players, or at least they thought he did. My friend Bob Welch was having blackouts at 23, destroying a promising pitching career, and his life, during the 1979 season. When I helped him write his book about rehab – “Five O’Clock Comes Early: A Young Man’s Battle With Alcoholism,” Bob told me how he hated Newcombe, was sure Newk was stalking him. And maybe Newk was. A big man, 6-foot-4, 220 pounds, with a prominent jaw and nose making him even more formidable, Newk had the run of the ball park. He wore elegant suits and snappy straw fedoras and would wander through the clubhouse, chatting with people. He was hearing how Bob had passed out in public, how the Dodgers had sent somebody to get him into his hotel room. At the end of the 1979 season, the Dodgers had a program with a major sponsor, and staged an intervention with Bob, and got him to The Meadows in Arizona. Bob came back and pitched for more than a decade and won the Cy Young Award with Oakland; he was sober when he passed suddenly in 2014. Newk was also there for Maury Wills when his life was crumbling and for Lou Johnson, the heart of the 1965-6 team, who came to the Dodgers for help. Newk said: “We’ve been waiting for you.” Newk made public speeches, represented the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and other outfits dealing with addiction. In between, he spoke about Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, his teammates and would-be mentors in Brooklyn. He told of the night that Robinson got weary of the black hotel in St. Louis with no air conditioning, and said, that’s it, I’m checking in at the Chase, with the white Dodgers, and did just that. Jackie and Campy died young; Newk carried their flames; he did it his way, as the song goes. In 1987, just before the 40th anniversary of Robinson’s debut, Al Campanis, the Dodger general manager (who was my friend), made some foolish and meandering statements about how black players lacked the “necessities” to be managers. This was a chance to say, well, racism is everywhere, you never know about people, but Newk knew Al Campanis, knew how Al had taught Robinson to play second base in the minors in 1946, knew that Al hung out with Latino scouts at the ballpark. During the uproar, Mike Francesa and Christopher Russo interviewed Newk on WFAN radio. and Newk said Campanis was no racist, he just bumbled a bit, and he labelled the end of Al’s career a “tragedy.” Newk was loyal to the truth as he knew it. In recent years, whenever I thought of the Los Angeles Dodgers, my last link to Brooklyn was the big man in the elegant suits who had the run of Dodger Stadium. Newk was a staple on old-timers’ day and other days of remembrance but he was as courant as the latest celebrity caught abusing one thing or the other. We have lost a good one. * * * Richard Goldstein’s obituary on Newk: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/obituaries/don-newcombe-dead.html Newk and Lou Johnson: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/14/sports/johnson-ex-dodger-tells-of-cocaine-habit.html Newk and Maury Wills and others: https://www.dodgersnation.com/don-newcombe-proud-of-his-accomplishments-in-the-community/2015/04/17/ Newk’s stats: check out the batting average and the home runs. The Dodgers usually have good hitting pitchers – the real baseball, none of this DH foolishness: https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/n/newcodo01.shtml Another view of Newk’s work with the Dodgers: https://www.mercurynews.com/2019/02/19/one-evening-with-don-newcombe-his-important-message-his-long-odds/ The Kavanaugh hearings have reminded me of two milestones in my own life.

One milestone came in my last few years of full-court basketball, in my late 30s, with players ranging from recent high-school varsity players to elders in their 40s. From fall to winter to spring, every Monday in the late ‘70s, the players in “adult rec” changed in one wing of the locker room while the boys on the varsity changed in the other wing. Over a row of lockers, I could hear the current jocks talking about life and times, but mostly girls – that is, who did what, and how often, and with whom. It was graphic and it was personal. This was before social media. Whether it was true or not, it was out there. This did not sound like my high school jock experience in the 1954 and 1955 soccer seasons. I am told that teen-age sex had been discovered back then, but boys did not talk about it in open locker rooms. I went home and told our two daughters, both coming along in the schools, “Boys will talk.” And some girls would be treated as prey. My second milestone came up the other day when the nominee for the Supreme Court – the Supreme Freaking Court – was recalling his idyllic days as student-athlete in a prep school (a Jesuit school, at that.) He seemed to retain the impression that some girls were from their crowd while others were outside their “social circle.” (The Jesuit magazine, America, has withdrawn its support for Kavanaugh's candidacy.) What happened to the dignified lady who testified is now up to the FBI. What a wonderful idea -- calling in professionals instead of relying on dotty senators. The hearing reminded me of my week in a rehab center early in 1981, when I was 41. I was working on a book with Bob Welch, the young pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, who had gone into rehab after blanking out in alleys and hotel corridors on the road. Bob was now sober – had pitched well for the Dodgers in 1980 – and I wanted to know what rehab had been like for him. The center – The Meadows, in Wickenburg, Ariz., said I could attend for a week, but I would have to participate in group sessions, not merely observe. One of the first things I noticed at The Meadows was that some people started off accepting that they were powerless. They were sad, and tried to deal with the feelings that made them drink or take drugs or abuse sex. But others were adamant that they had no problem. Why were people saying these things about them? Why were they making up stuff? And most of all – with volume rising and face distended and arms flailing – why the f--- didn’t people believe them? Why was everybody against them? Bluster seemed to be their stock in trade. Ward off the accusations with a swat at the air, a sneer, a bellow. I learned a lot at The Meadows. The sessions shook off a few memories of shame when I drank too much, smarted off too much. I learned I did not have to drink when I didn’t feel like it, which is now almost all the time. I had a great teacher. My friend Bob Welch stayed sober (as far as I know), day by day, for the rest of his too-short life. He knew himself. He knew the nature of the beast. One time he and my teen-age son Dave and I were in a restaurant in Montreal, and Bob was doing the play-by-play of the dining room. “Look at that guy,” Bob would say. “He wants to pour for everybody. That’s so he can drink more. Watch.” Sure enough, the stranger would cajole his companions to top off their glasses, so he could refill his. I learned from dear friends like Bob Welch and my recent pal (he knows who he is) who fight off the beast, day by day, and acknowledge it, and share the struggle. The book, "Five O'Clock Comes Early." is still out there. C.C. Sabathia of the Yankees relied on it when he checked into rehab. I thought about Bob the other day when I was watching a candidate for the Supreme Court who, when confronted with touching testimony (if murky external details), resorted to baiting senators: What do you drink, Senator? Did you ever black out, Senator? Maybe that is the combative reaction of a former high-school jock who (as he reminded us a time or two) lifted weights and played hoops back then, all summer long. Doesn't seem very judicial to me. Channeling my late friend Bob Welch, I reacted to the visceral bluster on the screen. “Whoa,” I said. “Whoa.” Until last fall, Bob Welch and C.C. Sabathia had one thing in common – the Cy Young Award, as the best pitcher in his league one year.

Now they have something else – rehab. Near the end of last season, Sabathia sought out a treatment center to face the addiction to alcohol that he was ready to acknowledge. “I started reading a lot while I was in rehab,” Sabathia wrote on March 7 in the Players Tribune website. “The first book I read was called Five O’Clock Comes Early. It’s by a former major league pitcher named Bob Welch, and it hit so incredibly close to home. Bob became a professional when he was only 21 years old and dealt with a lot of the same anxieties that I had felt, so he’d turn to alcohol for confidence. He ended up checking into a rehab facility, and when he came out on the other side of treatment he was a changed man. He ended up going on to have a great career after he got help.” Riley Welch read Sabathia’s story and alerted me. Riley is a ball player himself, a college and minor-league pitcher, now coaching pitchers in Honolulu. He’s always been proud of his dad, who died suddenly in 2014 at the age of 57. “It brings my family and me great pleasure and joy to see that now, almost thirty years after Five O'Clock Comes Early's initial release date, it is still helping someone live a healthier life,” Riley wrote to me. “I’m very proud that the book was able to provide inspiration for someone during a rough period in his life.” In 1980-82, before Riley was born, I helped Bob write his book, when his rehab was still raw and he needed to reinforce it every day – to verbalize that he was choosing not to drink when the guys were getting hammered in the back room of the clubhouse. Over the years, I’ve received dozens of letters from readers – almost always men – who said they were staying sober – that day – because of what they learned from Bob. I don't know if C.C. Sabathia knew Bob Welch. Bob won the Cy Young in 1990 with Oakland; Sabathia won his in 2007 with the Yankees. But baseball is a fraternity with frequent lodge meetings, and Sabathia grew up in the Bay Area, Bob’s long-time home, so maybe they did know each other. More importantly, Sabathia is taking an example from a pitcher who saved his career, his life, when he was just getting started. I can only imagine Bob’s enthusiasm when he heard that a colleague had taken the big step. Bob’s book was reissued in electronic form last year, with a new chapter I wrote after Bob’s passing. C.C. Sabathia’s testimony reminds Riley Welch that his dad is with us, with lessons to teach anybody with “the problem.” Riley added: “I know my father would be proud of C.C. for getting help when he needed it.” * * * Riley also enclosed a recent story by Barry Bloom, about how Bob Melvin, the Oakland manager, has put the bench commemorating Bob in a prominent spot at the spring ballpark. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/166395958/as-bob-melvin-appreciates-bob-welch-memorial There is no consolation for losing a friend way too young, but at least Bob Welch’s book on his alcoholism has a new life – in electronic form.

Bob died suddenly in June of 2014 at the age of 57. I wrote a tribute to him, how he went through rehab in 1980, at the age of 23, after nearly wrecking his pitching career. He stayed sober and wound up winning the Cy Young Award, but his real victory was sobriety. He set an example for others, particularly young people who think they are immune to being alcoholics at such an early age. Bob gives examples -- frightening, graphic, and illuminating -- of the acts and cover-ups of the alcoholic. His son Riley was the driving force behind the re-publication of Bob’s book. He wanted his dad to be remembered, for all the right reasons. I have written a new prologue and epilogue to cover the main points of Bob’s life after pitching. (There are also some links to stories about Bob, as well as a couple about alcoholism.) Bob always reminded people – and himself – that alcoholics need to be vigilant, day by day. I’m not an alcoholic, but I surely learned from Bob and my other friends that you don’t have to drink, at this moment. Of all the books I have written, this one has done the most good. Alas, the earlier versions of Bob’s book are out of print, but I hope anybody interested in “the problem” – particularly in the young -- will consider clicking off an e-copy of Bob’s book, via Open Road Integrated Media: http://www.amazon.com/Five-OClock-Comes-Early-Alcoholism-ebook/dp/B016XE7P18 Thank you, George Vecsey |

Categories

All

|