|

It’s too hot to go out in Southwest France, report my cousin Jen and her husband Sam. Bulletin: Wildfires in Nouvelle Aquitaine and Gironde, Meanwhile, London was bracing for 104-degrees Fahrenheit – which would set a record. Back in the southwest corner of Virginia, they are still digging out after the aptly-named Dismal River suffered a flash flood last week. I know that portion of Virginia, from my days on the coal beat. Decades of strip-mining – lopping off the tops of mountains to get at the coal – have destroyed the watersheds of Appalachia. (I wrote a book called “One Sunset a Week,” about a miner’s family in adjacent Russell County. Every time the heavens erupted, the rains washed down detritus from strip-mining, known as “red dog.” That was 1974.) If only the governors and senators of Appalachia knew about this. Perhaps they might do something. The prototypical politician from Appalachia is Joe Manchin of West Virginia. He must know the ultimate flood is coming because he’s fitted himself out with a yacht, anchored outside Washington. When the Potomac rises, Commodore Manchin is going to float safely downstream – but to where? The Commodore has been busy. Last week, he slipped up behind the helpless ancient figure of Mother Nature and whacked her with a coal shovel and stole her pocketbook. He did it by voting against the tax bill that would have at least recognized the danger of rising temperatures, and the role of fossil fuel, not only all around the world but in his home state of West Virginia. His Inner Republican said he was being a guard dog for fiscal sanity, blah-blah-blah, but we know better. We know that decisions that affect the future of world ecology are made by the (white) (old) men who are either rich or wannabes. The Commodore is not only a scientific authority but also a coal baron, via his family business. It’s in trust, the Commodore tells us. He knows nothing – just like it was a shock to him that his daughter, Heather Bresch, presided over a drug company, Mylan, when the price of EpiPens – used to treat allergic reactions -- soared to $600 a shot. This was a shock to the Commodore. These kids today never tell their parents anything. Maybe the flood on the Dismal River in neighboring Southwest Virginia was a shock to the Commodore. Maybe the flood in Yellowstone National Park was a shock to the Commodore. Maybe the heat wave in far-off Europe would be a shock to the Commodore, if he heard of it. But the Commodore doesn’t have time to monitor events in such distant places. He just wants to balance the books, like a good Republican, although he is nominally a Democrat, and make sure energy moguls continue to make an honest buck, so they can all afford yachts to escape the cataclysm, so they can float off to some safe place, like maybe the Marshall Islands. Oh, wait. The Marshall Islands are going under, day by day. But don’t tell Commodore Manchin. He is heroically standing up for his constituency – energy barons, coal-mine operators. He’s a man of the people. A few of them. * * * I seem to be writing a lot about Commodore Manchin these days:: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/write-about-west-virginia-she-said https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/watching-manchin-thinking-about-the-the-sopranos  Borrowed from that great asset, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news Borrowed from that great asset, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news (Laura Vecsey is a terrific news reporter; she proved it in two capitals of major states. She once almost bought a bit of land in a scenic portion of northern West Virginia that George Washington had surveyed. The other day Laura offered some friendly advice to her father, who was thinking about writing about the baseball post-season: “You know West Virginia; write about that.” So here goes.)

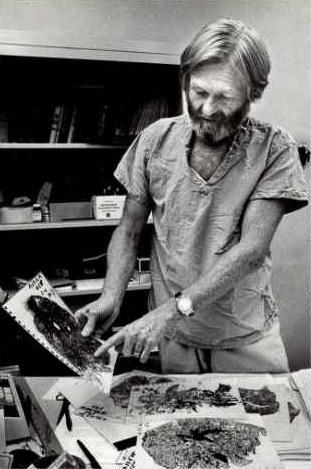

Joe Manchin was not in the spotlight when I was covering Appalachia in the early 70s. The governor of West Virginia back then was Arch A. Moore, who later did 32 months for campaign corruption. Manchin later became governor and is now a senator. Nominally a Democrat, he is doing his best to blow up bills that would protect the ecology and the people. He says his stance has nothing to do with the energy stock he divested. “It’s in a blind trust,” he often says. The governor now is Jim Justice, allegedly the richest man in the state. Some governors might be concerned about the water supply or the bleak future of the coal industry, but Jim Justice spends much of his psychic energy coaching the girls’ basketball team in East Greenbrier, W.Va., far from the capital of Charleston. He also wants to coach the boys’ team in East Greenbrier, but school officials are thwarting that little whim of his. Stay tuned. * * * West Virginia is not all grim coal camps and refuse from hilltop strip mining; the coal seams run out below the northernmost sector. One of my best friends recently spent a long weekend with three of her long-time girl friends in a remote cabin in the woods – had a great time, even though the fall colors had not yet arrived. She talks with great affection of her first couple of years in a West Virginia college. * * * The reason I love old-timey country music is from a few summers as a kid, spent in upstate New York, where you could tune in Kitty Wells, Hank Williams, the Carter family – clear as a bell, through the mountains, straight from WWVA in Wheeling. * * * One of my first trips to coal country was to report on Dr. Donald L. Rasmussen, who carried around slides of dead miners’ lungs – ravaged from years of work underground, inhaling coal dust. Some coal-company doctors used to tell miners that coal dust would cure the common cold, but. Dr Rasmussen displayed the grisly slides at public hearings or outside the headquarters of coal companies. * * * I also got to meet a member of the House of Representatives who cared – Ken Hechler, a World War Two vet, a New Yorker, and a writer, who settled in West Virginia and became an advocate of the miners, the poor, and ran for office – living to be 102. Hechler had a protégé, Arnold Ray Miller, a working miner who had absorbed the inequities of the business. In 1972, Miller – backed up by volunteers, those dreaded out-of-state college students, ran for president of the corrupt United Mine Workers. I traveled around with Miller’s cadre during the campaign; after the 1970 murder of the Yablonski family in western Pennsylvania, the campaign was under close protection – insurgent watchmen outside hotel rooms, everybody armed. Miller won the election in 1972, but nothing much improved. * * * In March of 1972, I rushed from Kentucky to West Virginia to cover the flooding of a valley, when a coal-mine refuse pond gave way in heavy rain, killing 125 people alongside Buffalo Creek, early on a Saturday morning. I interviewed next-of-kin and neighbors and learned that the company had sent a worker named Steve to bulldoze more earth onto the failing dam, high in the hills. That is to say, the company knew the danger but did not bother to warn the families downstream. My reporting helped inform a successful class-action suit, that did not bring back the dead. * * * The coal-mine carnage and the current conflict of interest by public servants would have been no surprise to one of the greatest figures in West Virginia history-- Mother Jones. Born in Cork, Ireland (home of strong women, I believe) Mary Jones left the potato famine for Toronto, lost her husband and four children, and became an advocate of organized labor in the U.S. – particularly West Virginia. (She often praised the valor of Black laborers.) To know more about her: https://history.hanover.edu/courses/excerpts/336jones.html https://www.biography.com/activist/mother-jones The people of West Virginia deserve better. In 2016, they voted, 68 to 26 per cent for Donald Trump, who soon abolished as many pro-ecology bills as he could. Many miners understand theirs is a dying industry. But guess who bellied up to Trump in the swarm after one of Trump’s first speeches? None other than Blind-Trust Manchin. Where is Mother Jones when West Virginia needs her? Outside, the storms – political and meteorological – were raging. Inside there was a winter concert, by students and, later, enthusiastic alums.

How sweet it was, to find shelter from all storms, to hear young people play and sing, with considerable skill. Our youngest grandchild was in one of the ensembles, but honestly the quality of the music and the spirit of the young people would have been an attraction by itself. This was Thursday evening at Schreiber High School in Port Washington, Long Island, which, as much as it changes, retains its home-town feel, on a peninsula, with a train line terminating there, and a real downtown -- 45 minutes by rail from Penn Station. The superb arts department produced one concert Wednesday and another on Thursday – an orchestra, a band, a choir, and then an ensemble for the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” A young woman gave a haunting flute solo; a young man led one section with a strong first violin; a young man played a specialty instrument that evoked the swirling of the sea. I was particularly captivated by the choir, having had the privilege of singing in Mrs. Gollobin’s chorus at Jamaica High School in the mid-‘50’s and admiring the choir members. I watched the faces of these young people as they put their hearts into “Rock of Ages,” and, I will confess, I remembered our chorus harmony from 1954-56, and I softly hummed to myself. I thought of the choir stars from Jamaica High – an alto who taught music at a university in Texas for many decades, and our two lead sopranos who came back for reunions, still beautiful and active well into their 70s. And then there was Eddie Lewin, star soccer halfback and lead in our musicals. (Lotte Lenya came to our performance of her late husband Kurt Weill’s operetta, “Down in the Valley,” with Lewin playing the lead role.) In later years, Eddie took a pause in his medical career to fulfill his dream of touring with “Fiddler on the Roof.” I thought about our choir and chorus while watching the young people of Port Washington as they performed so brilliantly in their own time. At the end, the leaders honored the tradition by calling all alumni of the music department to join them in Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Dozens of recent graduates filled up the sides of the auditorium. They were asked to call out their graduation classes – 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015 – and somebody said, “1976!” That was Jonathan Pickow, a well-known musician from our town, the son of Jean Ritchie, one of the great traditional folk singers and historians from her native Eastern Kentucky. (Ritchie Jean and her husband George Pickow – now both passed – lived high on a hillside in our town. First time I heard Ritchie was at Ballard High in Louisville, when we lived there, around 1971-2. She reassured Kentuckians that the steep hill on glacial Long Island made her feel she was still in Viper, Perry County. Jon has toured with Harry Belafonte, the Norman Luboff Choir and other choirs, has performed with Oscar Brand, Judy Collins, Theo Bikel, Odetta, Josh White, Jr., Tovah Feldsuh and my pal, Christine Lavin. And there he was, amidst musicians more than 40 years younger than him, talking respectfully of having been part of music programs at Schreiber High in Port Washington, back in the day. Music is classical; it provides shelter in all storms. * * * PS: Jean Ritchie wrote the classic protest song, "Black Waters," about strip-mining, which obviously the tone-deaf Mitch McConnell from Louisville has never heard. https://politicaltunes.wordpress.com/2014/01/31/jean-ritchie-black-waters/ https://www.nytimes.com/1984/04/16/arts/weill-s-opera-down-in-the-valley.html http://www.jonpickow.com/bio/ https://www.ket.org/education/resources/mountain-born-jean-ritchie-story/ https://www.allmusic.com/artist/the-cleftones-mn0000073914/biography The other night, the conscientious Chris Hayes did a documentary from West Virginia, with the impassioned Sen. Bernie Sanders.

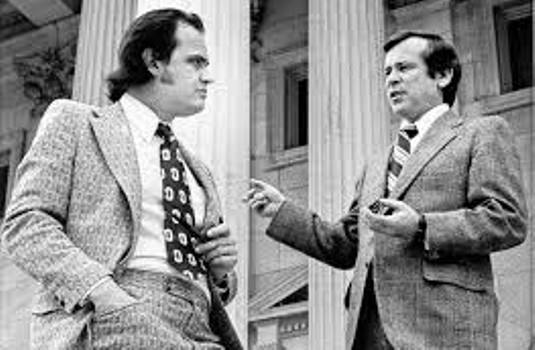

I couldn’t watch. The state already voted for the poseur, Donald Trump, last November by roughly 68 to 26 per cent over Hillary Clinton. It’s all so familiar. Living in Kentucky, I covered Appalachia for the Times from 1970 through 1972 and remained in close touch for many years afterward. I saw bodies fished out of Buffalo Creek after an earthen coal dam gave way. I saw the crusading Doc Rasmussen going to hearings with an autopsy slide demonstrating Black Lung. I covered a few coal-mine disasters and the Harlan strike of 1974, so grippingly captured by Barbara Kopple. So long ago. So courant. The only thing that has changed is that we know more. Technology has gotten better – and worse. Coal companies can push more detritus downhill into the streams and gardens of their own people and scientists can measure the damage to air and water and lungs more carefully. When I covered West Virginia, Rep. Ken Hechler was the Bernie of his day, speaking out against corruption and pollution. (Hechler passed recently at 102.) A miner named Arnold Ray Miller tromped around to speak against corruption in his union – and was elected president in 1972. There was often hope of change, of throwing out the rascals and the big-city corporations, but decades have gone by, and good people still want to work, and young people have no hope and are resorting to killer opioids pushed on them by the same kind of doctors who said coal dust was good for the common cold. Every reliable study says there is no future, no justification, for digging and burning coal, yet frauds like Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and Big Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who calls himself a Democrat, bow down to their masters from Big Coal. It is pathetic. The decency and the religion and the patriotism of people from West-by-God-Virginia make them susceptible to all kinds of drugs – crooked politicians, phony prophets of economic success. Hillary Clinton, in her own artless way, told people that coal mines would be shut down. So they voted against her. Of course, Sanders had won the Democratic primary in West Virginia, proving that people of that state are terribly bifurcated, at their own expense. One of the first things Trump did to Appalachia was to remove barriers to dumping waste into the valleys where people live. And Big Joe shook Trump’s hand after his first speech to Congress. My wife and daughter Laura (who used to cover rascals in Pennsylvania) told me the MSNBC program was terrific. Now it seems people in McDowell County are speaking up for health care and even Big Joe Manchin is getting the message that you can sell out your own state just so long. God bless Bernie Sanders and Chris Hayes and West Virginia, but I just couldn’t watch. Fred Thompson’s obituary reminded me of another time and place, when fewer public figures made me feel, well, I think the word is icky. In the very early ‘70’s, I was a New York Times Appalachian correspondent based in Louisville. There were giants in those days, who believed in government. Some of them were Republicans. I got to write about Sen. John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, Mayor Richard Lugar of Indianapolis and a young United States Attorney from Western Pennsylvania, Richard Thornburgh, who gave me a private seminar in jury selection that informs me to this day. One lovely fall day, I took a ride around Nashville with Sen. Howard Baker, who was running for re-election. He brought along his campaign manager, tall and droll, Fred Thompson. I don’t remember a word. My story included Baker’s Democratic opponent saying Baker was too liberal toward the antibusing movement. I only remember good conversations in the car and Fred Thompson’s pipe. For a lefty from New York, I was not at all surprised to see things from their perspective, and to enjoy their company. The Watergate break-in had taken place three months earlier. It was not mentioned in my story. None of us had any way of knowing Baker would be a major figure in the hearings, and that Thompson would become famous for whispering to Baker, as one of his chief assistants. I was not the slightest bit surprised when Baker was seen as a stalwart, honest man who examined the evidence against President Nixon. I followed their careers, as Thompson became an actor – well, he was always an actor – and a senator himself. Recently, I came across a story I had written in 1972, about possible legislation to limit strip mining – ripping coal from the surface of hilly Appalachia. The two proponents were Sen. Cooper from Kentucky (who was about to retire) and Sen, Baker from Tennessee, both Republicans, from coal states. I thought about the way current senators grovel in front of coal -- Joe Manchin of West Virginia (a nominal Democrat who sometimes seems like a nice guy) and Mitch McConnell of Kentucky (who does not, ever.) In the year of Trump and Carson and the nebbish Bush and the twerp from Florida I call El Joven, I remember a sunny day driving around Nashville with Howard Baker and Fred Thompson – and not feeling like I needed a shower afterward. What has happened? Two days in a row, the New York Times paid long and literate attention to two worthy people I happened to know – one a coal-region doctor, one a figure skater.

* * * I met Dr. Donald L. Rasmussen once – at a Black Lung meeting in Beckley, W. Va. Miners, wrecked in their 40s, were milling around, coughing and brandishing tattered papers of denial for medical benefits. In the swarm was a tall and red-headed doctor, as out of place as a Viking in a Bosch painting. Doc Rasmussen was one of those outsiders come to foment trouble among the innocent folk of Appalachia (as the coal lobby would say.) He carried a small rectangular box that could have held cigars or chocolates. Inside was a gray object, grainy and desiccated – a slide from a miner’s lung, available only upon autopsy. That’s when I learned about Pneumoconiosis – Black Lung Disease. Most miners had it, the doctor said. This was after decades of coal-region doctors attesting that coal dust was good for you – cured the common cold. Doc Rasmussen taught generations of miners and any federal welfare officials that would listen what miners’ lungs looked like after a few years underground. The coal companies never did run him out of Beckley. He died at 87 on July 23. Don’t know if Sam Roberts ever heard of him before, but he did right by Doc Rasmussen. * * * I met Aja Zanova when I was doing Martina Navratilova's book. Aja was tall for a figure skater, head up, shoulders out, one of the straightest shooters I ever met. Her career as a world-level Czech figure skater was cut short by the Soviet domination, and she defected to the United States, part of the Czech diaspora. I was lucky to meet her husband, Paul Steindler, the New York restaurateur, who was dying. Aja served as a surrogate big sister to Martina. I would run into Aja at tennis and skating events all over the world. She had news and opinions and was good company. She outwaited “our good friends” from the East (as Martina’s stepfather Mirek called the Soviets) and eventually she went back to Prague, greeted by 50,000 people in Wenceslas Square. The new Czech government gave her a medal and restored some long-confiscated family real estate. Aja wryly told me how some old acquaintances looked her up, said they had always been on her side. She died on July 30 at 84. I don’t know if Margalit Fox knew her, but the obit in the Times caught her strength. * * * I was toying with commemorating Jerry Garcia and Mickey Mantle, who both died in August of 1995, but here is my column linking them. Better I should honor Doc Rasmussen and Aja Zanova. The 40th anniversary of Buffalo Creek kicked up all kinds of flashbacks.

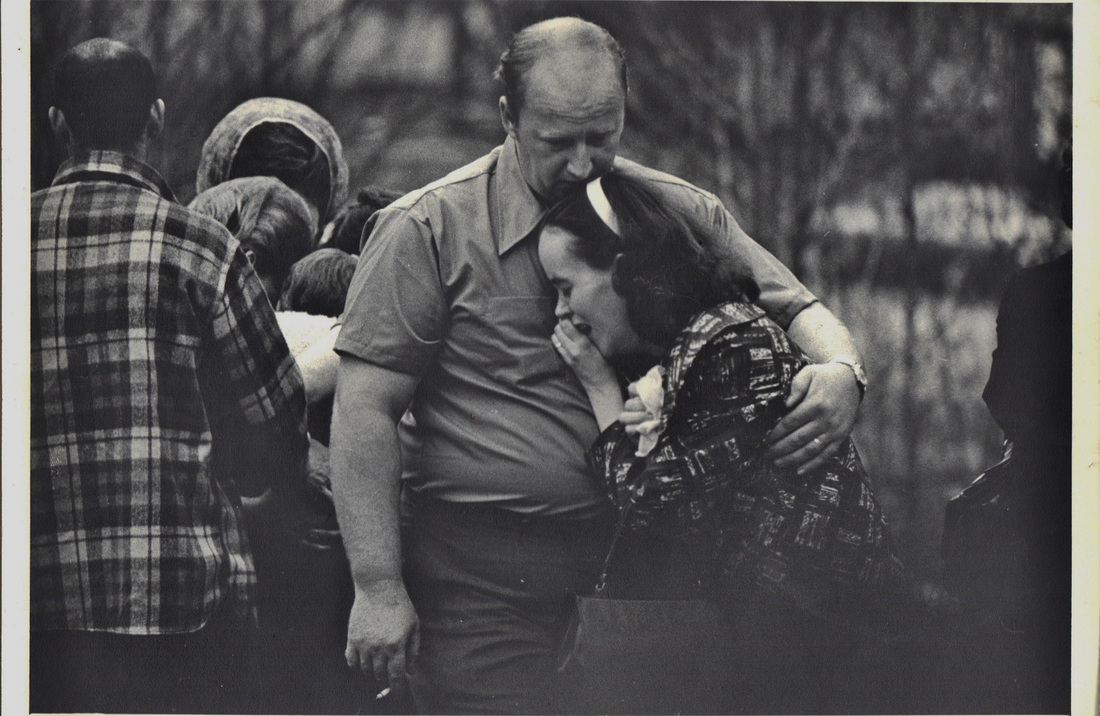

One of them was a glint of sunlight on a wire, stretched across the valley. I did not see the glint; fortunately, the helicopter pilot did. The official total of dead from the flash flood in Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, on Feb. 26, 1972, was 125, but it almost became higher. The helicopter episode came when somebody in authority offered The New York Times a place on an Army helicopter that was doing reconnaissance in the long narrow valley. As a reporter, you always accept these offers. I had been in helicopters before, but they always had doors and stuff. This one, as I recall, had a chain or belt stretched across a portal. I was strapped into my seat, but my inner core had the sensation of dangling out. It was eerie enough, trying to adjust to pickup trucks lying in creek beds, mobile homes stretched across roadways, lowlands flattened as if by a giant bulldozer, and knots of rescue workers, poking in the flotsam at every bend of the river. Not much was moving. We were heading uphill, where the coal company had placed an earthen dam to catch all the water and junk from the mine. Suddenly, I heard the pilot mutter something as he made an evasive veer, straight up, as I recall. We came to understand that he had spotted an electric or telephone line stretched across the valley. Forty years later, I have no idea how close we came. All I remember is the mixture of gravity and fear in my stomach. Whenever I think of Buffalo Creek, that little episode comes to mind. * * * The pistol adventure happened a few days later, when the Times home office asked me to check for more earthen dams in the region. I caught up with Ken Murray from Tri-Cities, who remains one of the great photographers of Appalachia. Ken and I had met right after the mine blew up at Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. We both went to the first funeral -- the shot man who had been using outdoor explosives indoors, during weather when methane gas is at its most explosive. We became a unit on subsequent assignments, with Ken contributing far more than this city boy ever could. This was when I learned to rely upon all the great photographers I have worked with. Ken and I drove around, looking for likely topography that might harbor an earthen dam. We were halfway up a hillside when the company guards caught up with us, clearly trespassing. I won’t say they were aiming their pistols at us, but they let us see the pistols. Ken and I were well aware that in 1967, the Canadian filmmaker, Hugh O’Connor, had been blown away after walking onto somebody’s property in rural Kentucky while making a documentary. My fellow journalists always told me that story – I think, to get a rise out of me, but they were surely doing me a favor, too. (The only time I ever had a gun actually pointed at me was by a very nervous young trooper wielding a nasty-looking shotgun during a riot in Baton Rouge in that same era. The trooper told me to produce my identification and I talked him through the process of my rummaging around in my pockets, and was he all right with that? I still do that whenever an officer tells me to produce my wallet. Nothing like play-by-play to calm testy officers with weapons.) Anyway, the coal guards interrogated us, until their boss arrived. As it happened , Ken and I knew the man from an earlier story we had done. He shook his head and said he was very disappointed in us. Meanwhile, Ken whispered, “Let’s get down to the state road; that’s public property.” We started putting one foot after another, telling our story walking, until we reached the highway. I told the foreman I had made a terrible mistake and would never get lost like that again, and we drove off. Didn’t find any earthen dams that day. Just guessing they’re still up there, waiting for the next hundred-year-rain in a week or two. Buffalo Creek.

After 40 years, the name still haunts me. I think of people and homes and cars, scattered like toys, demolished by a capricious child. The morning of Feb. 26, 1972, looked pretty much like coastal Japan during the tsunami of 2011, except this destruction was man-made. The coal company had created an earthen dam near the top of the valley, to capture waste slag and water from the mine. Apparently, they never counted on a heavy rain. They called it a "hundred-year rain." I would hear that phrase every few months, somewhere. I was working in Kentucky as a national correspondent for The New York Times when I got the call. The dam had let loose near dawn on Saturday morning. By the time I drove across to West Virginia, the death toll was heading toward 125. I went to a shelter at the local school and found a man who had been up on the hill tending to his garden when the dam broke, and he watched the wall of water sweep his family away. This was my second coal disaster, after Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. My boss, the great reporter and editor, Gene Roberts, had prepared me for covering Appalachia by telling me that if you spoke quietly and carried yourself respectfully – not like the stereotype of the network broadcaster -- people would talk to you, because they needed to tell their story. The man described watching his house tumble down Buffalo Creek, with his wife and children inside. He said they had no warning, despite the heavy rain on Friday. They all knew the earthen dam was up on the hill. Perfectly safe, the coal companies said. Then again, coal companies claimed coal dust was good for you. Could cure the common cold. * * * In my first hours in West Virginia, I got very lucky, in the journalistic sense. This was before computers and the Internet and cell phones. I needed a landline to call my story to the office in New York, so I knocked on a door, and an old lady let me use her phone, and then she invited me to stay for supper. After we said grace, she and her grown son casually mentioned that a friend of theirs had been up on the hill trying to shore up the earthen dam that morning. As the water exploded from the dam, their friend had suffered a nervous breakdown and was in the Appalachian Regional Hospital down in the valley. Poor feller, they said. That piece of information told me the coal company had known the dam was in trouble for hours before it blew. Yet the valley was not warned. The next morning the sun was out, and I found a lawyer from the regional coal company. I indentified myself as a reporter from the Times, and casually asked about the relationship with the major energy company in New York. He said the company still had to investigate the cause, and he added, “but we don’t deny it is potentially a great liability.” When the story appeared in the Times the next day, the lawyer denied saying it, but I let them know I had very clear notes in my notepad. And to this day, I still have that notepad, sitting right here on my desk, and every notepad I have used since. You just never know. * * * With the 40th anniversary coming up, I got in touch with Ford Reid, who was a photographer for the Louisville Courier-Journal back then, and has remained my friend ever since. Ford was at Buffalo Creek for over a week. I asked him to jot down his impressions, and he described the narrow valley as looking like “pickup sticks.” Ford described the scene at the high school: “Families huddled in corners with Red Cross blankets and perhaps a few things they had managed to grab before scurrying up the hillsides to avoid the wall of water." Ford added: “Military search and rescue helicopters used the football field next to the school as a landing area. At the first sound of an incoming chopper, people would rush out of the building and toward the field, hoping that a missing relative or friend would step off the aircraft. When that happened, there were shrieks and tears of joy. But it didn’t happen often. Mostly there were just tears.” * * * We all went to funerals in the next days, hearing the plaintive wail of the mourners and the mountain church choirs, a sound that still cuts through me. My original reporting that the company had a man on a ‘dozer up on the hill during that heavy rain held up, as survivors told their stories of not being warned. In the years to come, the testimony of the survivors was used in three class-action suits that yielded a total of $19.3-million, according to the records. I do not know how that worked out for the 5,000 people displaced or killed by that flood. From what I see and hear, nothing much changes in Appalachia. Nowadays, I hear people talk about the solution for the energy crisis. The industry and politicians like to use the phrase “clean coal.” Aint no such thing. * * * For more about Buffalo Creek, I suggest: http://appalshop.org/channel/2010/buffalo-creek-excerpt.html http://www.wvculture.org/history/disasters/buffcreekgovreport.html http://wiki.colby.edu/display/es298b/Buffalo+Creek+Disaster-+WHAT |

Categories

All

|