|

I’m finishing up a four-day sabbatical from watching baseball – although not necessary from thinking about baseball, talking about baseball, writing about baseball. Fact is, two friends – former ball players, now faithful e-mail correspondents, have added to this missive – and a few family Mets fans pulled me back into the game when I was supposed to be resting my brain. I had made a conscious decision to avoid the All-Star Game on Tuesday, plus that gimmick called the Home Run Derby on Monday. Like many Mets fans, I had my fill of mood swings in the first half of the season – the Mets stunk, too many pitchers I never heard of, too many rumors that Pete Alonso would be scuttled. But then the Mets made a gallant run in the month or so before the All-Star Game, rushing into third place. I watched so much that I could justify ducking the all-star events. Plus, I cannot stand network baseball -- too much witless testosterone from old stars, too much born-yesterday overkill from the network booth. I wanted the terrific Mets commentators – Cohen, Darling, Hernandez, plus Good Old Howie Rose on the radio -- to rest their lungs, their eyes, their wits. And I would do the same. However, on Tuesday evening, I was listening to the dulcet tones and expertise of Terrance McKnight on WQXR-FM, when I heard my cellphone popping. It was a family member griping about the garish uniforms on the all-stars, a comment backed up by two family Mets fans upstate. I flicked on the tv, saw the ridiculous gear --convinced all over again that Commissioner Rob Manfred has no feel for the sport. Bad enough baseball is now in bed with gambling dens. Now it is hustling overkill uniforms. Back to classical music. However, two friends were still buzzing about the all-star uniforms. I heard from Bill Wakefield, who pitched for the Mets in 1964 and has saved up a lifetime of memories. (Pitching to Willie Mays! Running around New York with Hot Rod Kanehl! Studying Casey Stengel up close!) Now a retired businessman in the Bay Area, Wakefield proposed baseball switch to uniforms sported by barnstorming teams with Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Good idea. Wakefield wrote about the first all-star game he remembered from his youth in Kansas City – a rain-shortened game in Philadelphia in 1952, won by diminutive lefty Bobby Shantz. Yes! I also heard it on the radio. Wakefield’s reverie triggered my memory of the first All-Star Game I attended – 1949, my father took me to Ebbets Field, great seats behind home plate. For whatever reason, one of my strongest memories is Andy Pafko of the Chicago Cubs, getting a hit, running the bases in the the Cubs’ traditional home uniform, with red logo. What a concept! I sent my Pafko memories to Wakefield, and also to my friend, Jerry Rosenthal, all-conference shortstop at Hofstra College in 1960, then two years as an infielder in the Milwaukee Braves farm system. Jerry – from Madison High in Brooklyn! – had the immense good fortune to study under farm-system coaches Andy Pafko (who had been traded to Brooklyn in 1951) and Dixie Walker (the Peepul’s Cherce in the mid 1940s.) Jerry, later a schoolteacher in Brooklyn, came through, as I knew he would, with his memories of Pafko and Walker. From Jerry Rosenthal:  I was thrilled by seeing that Andy Pafko baseball card! I will never forget Andy ; one of the finest men I ever met! During the Braves' minor-league spring training camp of 1962, in Waycross, Ga., I got up the courage to asked Andy about "the shot heard round the world"! It was in the "rec" room, after one of our afternoon games. Somehow, I was one of Andy's favorites. That was partly because I was from Brooklyn and we could talk knowledgeably about the old Dodgers and the wonderful Brooklyn culture of the early 1950's! By the way, Dodger fans loved Pafko! Andy told me that he actually cried when when the Dodgers traded him to the Braves! He also said that his time in Brooklyn were his happiest years in baseball!” (Jerry recalled how he asked about Pafko’s moment in 1951, watching Bobby Thomson’s home run sail over his head into the lower deck at the Polo Grounds.)

Jerry wrote: "I finally asked him about Bobby's historic "shot." "I distinctly remember Andy saying: "I played many years with the Cubs, so I knew that that any hard-hit ball in the air that was pulled by a right handed hitter was going out! He added that "he could, at times, tell by "the crack of the bat" when the ball was gone"! He said he “heard it clearly." "Maybe that was because of the sparse crowd at the PG on that momentous day! "That iconic picture of Pafko looking up at the lower- left field deck is branded in the collective memory bank of even the casual baseball fan! "Most fans still think Bobby's homer was hit into the upper deck, maybe that was because it looked like Andy was looking high up! Andy told me that he always got this question: "Did you think you had a chance to catch the ball?" It was impossible to jump anywhere near a wall that was fifteen feet high! "Durocher actually commented on the rarity of homers being hit into the lower left field deck; most homers were hit into the overhang of the upper deck! Bobby hit a sinking line drive off a fastball! it quickly disappeared into the lower deck! "As fate would have it, Bobby Thomson was traded to the Milwaukee Braves and roomed with Pafko for a few years! They became close friends. At first, Bobby wore his number 23, the same number as when he was with the Giants, until he switched to 25 the next year. "I wore that hand-me-down number 25 jersey at Eau Claire. Wish I had that jersey today with "Thomson" embroidered in red thread on the inside. By the way, picture available.) "Here's a fact that most baseball fans never mention: Andy Pafko took over the third base position from Stan Hack in 1945 and played third base in the Cubs - Tigers World Series. "The Associated Press named Pafko to the All Star game as the starting third baseman, even though the game was not played in 45' because of the War. "So Andy was one of the rare major leaguers who made the All Star team playing two positions ( all told- Pafko played in five All Star games - one at third base and four as an outfielder ). "Pafko ended his wonderful ML career by being replaced in right field by Hank Aaron! Not a bad way to go out!" *** (Jerry, who was in several English classes with me at Hofstra, finished with a flourish:) "George, couldn't agree more about those beer-league uniforms worn by All Star players! It irritated me so much I watched part of the Republican Convention! "I took an antacid tablet and went to bed! " *** GV: I have the feeling baseball is going to come in handy in the months to come.

16 Comments

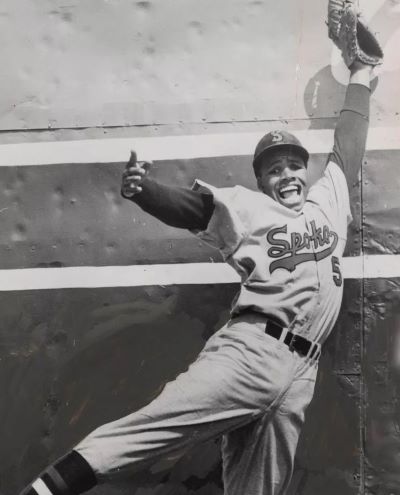

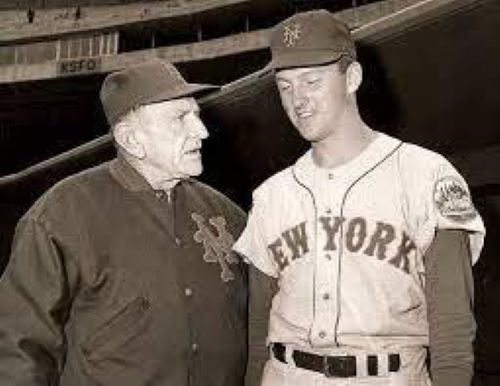

Bill Wakefield pitched only one season in the major leagues – 1964 – but he finds himself tied to Willie Mays, who died the other day at 93.

We both got to see Willie Mays up close – me as a young sportswriter, realizing that Mays was uncomfortable with the new breed of mostly-New-York writers (The Chipmunks) who asked him layered questions. Willie was not the bubbly young star described by the writers who had covered him back in his Polo Grounds days, when he was a kid out of Alabama. Wakefield was a rook out of Stanford University in 1964. He saw Willie Mays at 60 feet, 6 inches – close enough to justify the Willie Mays baseball card he had treasured as a kid in Kansas City, Mo. I was not surprised this week when I received an email from Wakefield, talking about 1964. The two of us have Casey Stengel and Hot Rod Kanehl and Willie Mays in common, “Willie's passing is being covered with proper respect by the finest sports writers in the nation. I agree with all their tributes. I cannot add to their wonderful admiring thoughts,” wrote Wakefield, now retired in the Bay Area. “But…my modest contribution to my friends,” Wakefield continued. “Everyone has a personal take on what a hero's passing at 93 means to them. “1951 - Card below - Butch and I ( age 10) open baseball card bubble gum packages on our front porch in KC. "Hey here's a Willie Mays - " My observation - Willie is EXACTLY 10 years older than me. Willie 5/1931 Billy W. 5/1941. Thanks to my dear mom Bobbie -- didn't get thrown out and I've still got the card!!!!!!” (GV: Mothers get the rap for tossing out old cards and autographs, in the name of order.) Wakefield continued: “1961 - I'm playing first year with Cardinals -- Lancaster Red Roses -- I'm 20 and Willie is 30. I wonder - maybe at some point I'll face Willie.” Then it was 1964, and Wakefield was a rook with the hideous but amusing Mets, studying Casey up close. The man on the trading card materialized in Wakefield’s life on May 15, 1964, as the Mets flew west for a weekend series with the Giants. They actually had a 4-2 lead in the eighth inning when….but let the great and invaluable website, Retrosheet, tell the story: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B05150SFN1964.htm There is no suggestion that Willie nearly hit one out – just a fly ball to Jim Hickman. Wakefield got 6 outs against a terrific team. Wakefield started against the man on the playing card on May 31 in Shea Stadium. This time he gave up a run-scoring single to Mays in the first inning, and was removed after two innings. The game went on so long that Casey was ruminating about putting Larry Bearnarth in the game -- not a bad idea, except that the two college boys had already pitched in that game. Bearnarth and Wakefield did the most logical thing – dressing in civilian clothes and slipping into the stands and sipping a cold beer and witnessing manager Alvin Dark switching Mays to shortstop for the 10th, 11th and 12th inning. (Dark had used Mays for one inning the previous season: https://www.cbssports.com/mlb/news/photo-of-the-day-willie-mays-shortstop/ The second game in 1964 went 23 innings and, of course, the Giants won. Wakefield would see Mays again in August in Shea Stadium: “I throw Willie a good sinker ( I thought) down and in ( It WASN'T a low hard slider!!) -- he hits it out off the scoreboard in right center …inside-out swing . Loud LOUD!! crowd cheer -- Mets fans / Willie fans!!” No shame in being stung by Mays, who would finish with 660 home runs. Wakefield’s list of Mays sightings continued to 1973: “I play in an Old-Timers game at Shea -- vivid memory -- I'm the old timer and Willie is still active player (his last year) for the Mets. Pre-game Mets Clubhouse exchange - DiMaggio (The DiMaggio) is dressing next to me -- Willie comes over. Big smile.” "Hey Joe" - and I get a head nod!!” “Willie is 42 I'm 32.” “2024 -- I still have my Willie card. Willie passed away at 93. “RIP, Willie. A sad day. My hero.” Some of the greatest players ever – Ted Williams, for example – speculated that Mays was the best. This judgment certainly came out in the stirring obituary by Richard Goldstein for The New York Times:puhttps://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/18/sports/willie-mays-dead.html And there was a lovely column by Kurt Streeter, the last NYT sports columnist before that newspaper entered a compact with some sports website. I had no issue with Streeter describing Mays as stumbling with the Mets in the 1973 World Series. Bless his heart, Willie stayed active into athletic old age, and he lived to be 93 – and people remember him for “the catch” in the 1954 World Series. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/18/us/willie-mays-death-baseball-legacy.html Bill Wakefield can proudly display his Willie Mays card, and he can recall Willie’s three innings at shortstop in that monumental game in 1964. I did not remember Mays’ four career innings at shortstop but they must have invaded my brain, because I once wrote about picking an all-star team in the mythical Game to Save the World. As I recall, my choices for outfield were Ted Williams, Henry Aaron and Babe Ruth (with apologies to the likes of Roberto Clemente, Joe DiMaggio, Stan Musial and Mickey Mantle.) And what about Willie Mays? Just like Alvin Dark,I put Willie at shortstop, on the theory that Mays, whether at center field or shortstop, was the greatest baseball player ever. *** On the 50th anniversary of Willie Mays’ immortal catch, I wrote about how Arnold Hano wrote a slim masterpiece of a book about the game: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/29/sports/baseball/hazy-sunshine-vivid-memory.html?_r=0 ### It’s October and the Mets are in the post-season, so right away it is obvious that this new book is a heavy case of fiction.

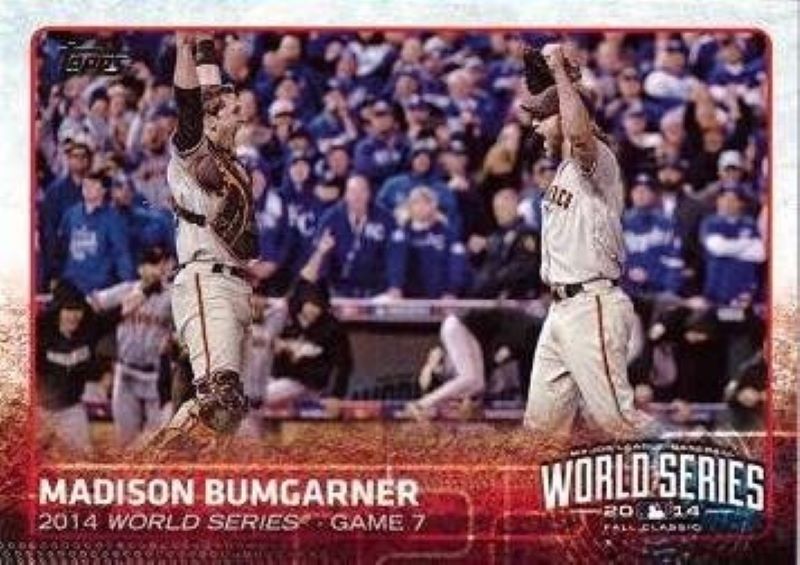

The 6-foot-5 rookie pitcher and the young catcher are having an affair. Roomies. Love at first flashing of the signals. Hence the novel “Curveball,” by Eric Goodman, published this week by Post Hill Press of New York and Nashville. Goodman is such a Mets fan that he handles the sweet ironies of the Met condition – off the top of my head, including Casey and the bed-sheet banners. Marvelous Marv missing two bases, not one. Swoboda’s diving catch. Mookie’s dribbler. Santana’s no-hitter with an asterisk from an ump. DeGrom-the-Pheenom, vanished without a kind word. Nowadays the Mets have an owner who wants to build a gambling den next to the ballpark in Queens, and call it an oasis for the working class. And meantime the franchise falls apart. Oy. Then again, the Mets have always been a sweet-and-sour franchise. Now Eric Goodman, Yale ’75, has written a second novel about the improbable poignancy of the Mets, even using the real name of the franchise because, you know, you couldn’t make up this stuff. The Curveball in question is tossed by life – a 6-foot, 5-inch pitcher with a wingspan, whose father and grandfather nicknamed him Two-J’s, that is, Two Jews. Jesse Singer figured out long ago that he is gay, and he doesn’t try to have it both ways. He is gallant to the sweet young woman who offers to be his decoy; but he knows he is attracted to the young Mexican catcher, Ramirez, nicknamed “Rah,” who is going to make the team this spring of springs. Jewish Joe Singer has been in an Eric Goodman novel before – “Days of Awe,” which in 1992 prompted me to write a sports column in The New York Times. (Honest, a sports column in The Times, the olden days. You could look it up.) https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/27/sports/sports-of-the-times-commish-a-literary-heavy.html Jewish Joe Singer got in trouble for not reporting a random suggestion (from his bookie father) to affect a game for gambling purposes. This was back when Baseball Commissioners like Bart Giamatti and Fay Vincent scorned gambling; Jewish Joe’s career veered into foul territory. “Curveball” contains three generations – Grandfather Jack has a lusty lady friend in South Florida. Father Joe is seeking modern treatment for prostate cancer that involves a new procedure in, of all places, Portugal. And Jess Singer is trying to make the varsity Mets squad, without calling attention to himself. The novel reflects how many players have been forced to keep their secrets. Glenn Burke played for the Dodgers and came out in 1982 when he retired, and he died young. Billy Bean, who played six years in the majors and came out when his career was over, and to baseball’s credit has beeb the official senior vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion. (Bean is currently fighting acute myeloid leukemia; his effective counterpart in the book is named Dean.) Goodman does a fine job depicting the conflicts of a young player – even as the Web leaks rumors about the rookie pitcher. Goodman’s other baseball novel – three decades ago! – brought Jewish Joe Singer to the “days of awe,” the very early fall, the time of Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax, who found their own ways to honor the Jewish holy days. The lore of real-life Jewish superstars. The Mets in this novel put a little extra pressure on the broad back of rookie Jess Singer – Number 32, once worn, and never to be worn again, by Sandy Koufax, once hailed in a winter baseball writers’ skit as “Sandy/you’re a Jewish Walter Johnson/you’re a dandy." In this knowing, compelling novel, Two-J’s path is his own. So many bad things going on, sport is the least of it.

But sport teaches you to hope, to endure – an experiment in a test tube. Take Edwin Diaz of the New York Mets. Last March his Puerto Rican national teammates piled on him in a victory scrum in the World Baseball Classic. The weight, the motion, crumpled his right knee. Within minutes, fans and players and doctors alike knew he would not pitch for a long time, or maybe ever. The gloom took over. If you ask me, the loss of Sugar Diaz caused the Mets to go into a shell, made stalwarts like Pete Alonso and Jeff McNeil try to over-hit the ball, put pressure on creaky elder pitchers – effectively ruining an entire season. Mets fans (and Mets writers) tend to think we are experiencing the mood swings of all humanity. We are from New York, representing New York, and we tend to think it is the center of the universe. So the loss of Edwin Diaz and his sizzling sideways slider put the entire planet off kilter (including things that really are important.) The season was empty. Darkness enveloped the land. The world was out of kilter, without the loudspeaker blasting the Edwin Diaz entrance anthem, “Narco,” recorded by an Australian known as Timmy Trumpet. Would we ever hear it again, see it again, cheer it again? Tonight (Monday, March 11, 2024) we heard it again, in an exhibition game in Florida. After a year of rehab and work, Diaz made his return in a spring exhibition game in the Mets’ home ball park in Florida. An electrical failure seemed a bad omen in the first inning, blacking out 10 minutes of tv, but the game returned, and in the fourth inning, the screen showed Diaz slipping into the bullpen, to warm up, as if he had never been away. In the top of the fifth inning, the sound system blasted the music of Timmy Trumpet, the ritual in our souls from the 2022 season. Edwin Diaz jogged to the mound and struck out three straight Miami hitters – all of them major-leaguers, not bushers filling out a road exhibition roster. His slider slashed at an impossible straight line from 90 degrees to 270 degrees, across the plate. Three straight strikeouts. Not even the emotional Mets fans could have hoped for this. Then Diaz skipped off to the home dugout to be embraced by staff and teammates. Back home in Long Island, all the bad stuff in the news – the fighting, the starvation, the threats, the bombast, the stupidity -- was temporarily overshadowed. Between innings, Diaz was interviewed Michelle Margaux, the sideline reporter, and I scribbled down phrases in quite decent English, like, “I feel good…amazing…in front of the crowd…I was making pitches….I want to say thank-you…I spent time with my family, my kids, I had time with my friends, and I was working hard…I missed my teammates…we are a family, really close….” Sugar Diaz said he had missed the trumpet at the ball park – but at home, he added, his two children often played “Narco,” the blare of Timmy Trumpet, which clearly revived the spring in the reconstructed knee of Edwin Diaz. So maybe this is the start of something – light instead of dark, warmth instead of wind, perhaps even, do I dare say it, sanity instead of madness. I am not sure I love the new ownership of the Mets – making Pete Alonso dangle, listening way too much to the analytics dweebs who value lusty longball swings rather than professional hitting strokes. In the Cohen stewardship, I have been brushing up on my Italian, the quote from Dante’s Inferno, that I memorized years ago: “Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate.” (Abandon all hope, ye who enter.) In the daily grind of baseball, the buzz lasts only one night. But after watching the sliders of Sugar Diaz, I have hope, and that is something. I am so thrilled that the New York Times obituary editors ran a lovely obituary of Joe Christopher, a member of the early New York Mets – and my friend over the decades.

Joe touched a chord in me because he was mysterious and deep. I have learned more since he passed last week, from his daughter Kameahle Christopher. I also collected memories of Joe from two of his old teammates. In case you miss the NYT obit, here it is (for those who can access it). It is written by Richard Sandomir, now an obit writer, but previously a star sports-media critic (back when the NYT had a sports section.) https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/05/sports/baseball/joe-christopher-dead.html I became intrigued by Joe Christopher in the first year of the Mets when he was a backup outfielder. Joe was from St. Croix, apparently the first player born in the Virgin Islands to play in the major leagues. He was a mix of cultures and languages, introverted, but also comfortable chatting with some of the young Chipmunk writers covering the club. “I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am,” he would say, softly. Sometimes he would chat with me about mysterious religious trends. I don’t claim I understood, but I think he sensed he had a friend. He was up and he was down with the Mets but in 1964 he played regularly and batted .300. (The obit tells how in the final game he dropped a bunt single in front of old Ken Boyer of the Cardinals to pretty much clinch the distinction of being a .300 hitter. In the pressbox in St. Louis, I almost cheered out loud.) His career sputtered again in 1965 and he was soon gone from the majors. Recently, two former teammates had nice things to say about Joe: Larry Elliott, a fellow outfielder in 1965, sent this memory: “I was trying to break up a double play against Philly. I did not get down in time and Ruben Amaro hit me in the back of my head with a throw. It was my fault. I was in the hospital for five days and Joe was the only one to come and visit me." My e-pal, Bill Wakefield, sent his memory of 1964, when he was a rookie out of Stanford and reported to the Mets’ spring hotel in St. Petersburg, Fla. “The front desk says, yes, we will give you a room, and assign your roommate. So I take my suitcase to the room. Open the door, and inside is a startled Joe Christopher. I said, ‘I’m Bill Wakefield and I’m your roommate.’ He seemed surprised but said, fine” (Wakefield doesn’t need to note that Blacks and whites were not rooming together in those days. And Christopher, who had been introduced to segregation in the U.S., was surely aware of that.) Shortly, Wakefield received a call from Lou Niss, chain-smoking, worry-wart travel secretary of the Mets “Come to come to the lobby immediately. I assume it's to get instructions -- don't drink in the hotel bar -- that's Casey's spot -- don't be late for the bus -- wear shower shoes on the bus not spikes, etc. “He says – ‘ Bill we are moving you in with Larry Elliott -- make the change immediately.’ And sort of as an afterthought, he said -- I paraphrase – ‘Baseball has made progress but we are not ready for black and white roommates yet." “I have no idea -- I just want to do all the right things. So I go back down to the room -- Joe is still there -- he kind of smiles at me -- and I said Lou Niss has assigned me a different room. “I always worried that Joe thought I had complained and that was the reason for the switch. I really didn't care. "So I packed up and moved to Larry's room.Joe never mentioned it again. He and I became pretty good friends. “Joe and I laughed about it over the course of the season. He even got a big smile on his face and would say ‘Nice going, Roomie!!!’ Great guy.” I have one more memory of Joe, who could wiggle his ears with the best of them. A knot of Mets writers were taking the sun behind the Mets’ dugout during a game in Chicago in May of 1964. As the Mets frolicked to an unforgettable 19-1 final score, Joe would trot in from right field after each inning, levitating his cap with his ears – just for the writers’ sake.” Joe’s major-league career fizzled but we kept running into each other. In the late 60s, I was in Puerto Rico writing for Sport Magazine about Frank Robinson managing a team in the winter league. I was at a game in Caguas when I spotted Joe playing for Santurce…and we agreed he would ride back in my rental. Then he won the game with a grand-slam homer in the ninth inning and the fans were so annoyed that they made motions to tip my car over. We laughed about it all the way back to Santurce. I always reminded him how he almost got me killed. Joe and I ran into each other in the 1980s near Times Square. He was carrying a large rectangular portfolio used by artists to protect their work. He came up to the Times for a while, but I never saw his work -- part of the mystery of Joe. The other day, I chatted with Kameahle Christopher, a paralegal with Amtrak, who lives outside Baltimore, and asked about her dad’s inner life. “He was interested in pre-Colombian art,” she said. “He was in touch with the ancients, the Olmecs and Mayans. He was into numerology…would ask your birthday, would predict things,” Kameahle said. “He was gifted spiritually.” I asked her about her dad’s childhood and she said he was raised in Oxford, a small settlement in St. Croix. “He grew up in a small house in the mountains,” she said. “He walked everywhere, and when he came home at night, he learned to follow the North Star. He said, “‘I’m not going to grow up like this.’ Nobody had ever left the islands. He endured hardships, but he used to tell himself, ‘I’m Joe from Oxford…and if I have to walk, I’ll walk.” In his later years, Joe wanted a job teaching baseball; “he carried his baseball gear in his car,” Kameahle said. Joe would coach somebody for the joy of it, remembering how much he had learned from coaches like Rogers Hornsby, Sheriff Robinson, Paul Waner – and his driven roommate with the Pirates, Roberto Clemente. After talking with Kameahle Christopher, I felt I knew her dad better – where his inner strength came from, standing in the clubhouse, a marginal Met, telling young writers from New York: “I’m a better ball player than you guys think I am." Kameahle’s loving portrayal made me miss him even more. ## They pitched for the Mets in different centuries – Jacob deGrom at the start of his career, Roger Craig near the end of his.

They both won over the fans – deGrom for his long-haired exuberance in his early years: Craig for his gnarly perseverance near the end. DeGrom was shut down this week, at 35, facing perhaps two years after Tommy John surgery; Craig died at 93. *** In deGrom’s final years with the Mets, I always felt I was watching his last game. The Mets never hit for him; that flaw was not of his making. He had so many injuries, yet he gritted himself through five, six, seven innings before trudging off the mound, leaving behind a streak of strikeouts but not so many victories (82-57 record in nine truncated seasons with the Mets.) In a time of gigantic bullpen staffs and strangely influential analytic types, deGrom seemed temporary, vulnerable, doomed in a professional sense, despite the pitches that curved and slid and sizzled. It was pure baseball joy to watch him – fielding like the shortstop he once had been in college, swinging the bat like the daily hitter he could have been (and who is to say, maybe still could be?) He was a complete ball player, except for the flaws. Then he was gone, like a main figure in one of baseball’s strange layer of supernaturalism in “The Natural” or “Damn Yankees,” or “Field of Dreams.” Flash. Bang. Gone. Why did Jake go? Without getting into the dollars, it seems to me that the Cohen Mets made a respectful, calculated offer, based on the belief that deGrom’s apparatus would fall apart one day soon. The Mets front office seemed to be waiting for a sucker franchise whose officials did not read the papers or listen to talk radio or consult the available analytics. I have a parallel theory: As the Mets fell apart at home in the post-season last year, fans booed Chris Bassitt as he trudged off the field. “Shame!” I yelled at the TV. Fans in grand old franchises like St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, would not boo, even as a season was going down the drain. At the time, I wondered what Jacob deGrom, from central Florida, felt about that display of venom from Big Town? Was my question answered when deGrom took all that money from Texas and departed without one overt farewell or explanation or thank-you to Mets fans, at least one that crossed my consciousness? Whaever. I hope Jacob deGrom comes back -- in some vestige of that floppy youthful mop of hair and that nasty arsenal of pitches. Life owes him a few breaks. *** Roger Craig had a different kind of career. He turned up with the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers, tall and slender, ahead of that lefty from Brooklyn, Sandy Koufax. He helped win the World Series – in 1955, “This Is Next Year” -- and then he went west with the Dodgers and helped win the 1959 World Series. In 1962, Craig was part of the expansion team in New York that had to fill the awful Dark Ages void left by the Dodgers and Giants. Craig’s mellow North Carolina accent and kind disposition helped influence a clubhouse after too many losses. In 1963, on a losing streak of 18 games, Craig switched from his No. 38 to No. 13 and was the winner when Jim Hickman hit a grand-slam home run against the looming left-field stands. In those two epic formative years in the Polo Grounds, Craig left his mark on the club – as did Richie Ashburn formerly of the Phillies and Gil Hodges formerly of the Dodgers. Never underestimate experience and leadership. Let me say this about the Dodger presence, commemorated in Roger Kahn’s classic book, “The Boys of Summer,” about the Bums of Ebbets Field. That team had many strong personalities and mature leaders, including Pee Wee Reese from border-state Kentucky, who set a tone in the clubhouse. In the last months of Ebbets Field, Cap’n Pee Wee noticed a young outfielder, Gino Cimoli, showered and dressed and heading for the door, in the still-promising late afternoon. “Gino,” Reese drawled. “If you’re in a hurry to get out of the clubhouse, you’re in a hurry to get out of baseball.” Cimoli sat down, maybe had a beer, maybe chatted with Dodgers around him. The Brooklyn Dodgers were a true team. Roger Craig came along in that milieu, and he passed it along to a motley squad of “Amazing Mets.” He pitched and he often lost and talked baseball and looked the writers in the eye and answered questions. In 1964 Craig was liberated, helping the Cardinals win a World Series. Later, as a coach, he taught a generation of pitchers to throw a split-finger fastball. Later, Craig managed the San Francisco Giants to a championship -- courtly, wise, always remembering familiar faces from those epic 1962-63 season in the rusty old Polo Grounds. When Roger Craig passed, Ross Newhan, long-time baseball writer for the Los Angeles Times, wrote this on Facebook: “Roger Craig, the original Humm Baby, died Sunday at 93, and I couldn't be sadder. There was no manager's office I more enjoyed walking into, no spinner of stories I more enjoyed inscribing. He won two World Series as a pitcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers, moved to L.A, and eventually became manager of the dreaded Giants, who never seemed quite as dreaded with Humm at the Helm. He was quite the guy, and I know my sadness is shared by Corona's Marshall family, Michelle being his granddaughter and Riley his great granddaughter, both frequent visitors to his San Diego Counthome. RIP Roger, you were one of a kind.” I think I can speak for the writers from those years: Ross Newhan got it right about Roger Craig. ### As of this moment, the worst seasonal record in the history of the major leagues still belongs to the 1962 Mets – 40 victories, 120 losses, for a nice round percentage of .250.

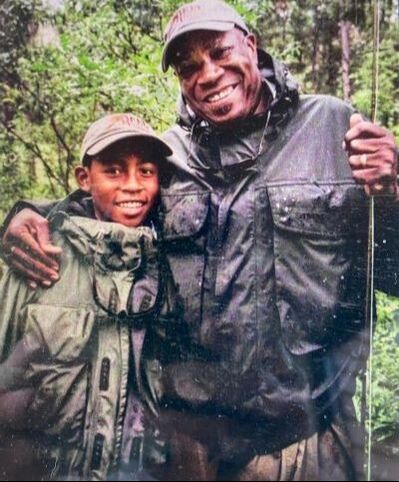

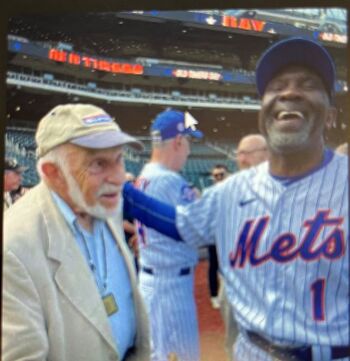

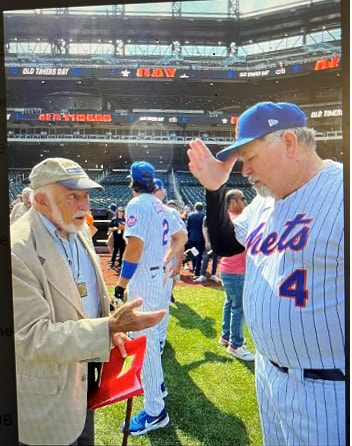

However, it looks as if the Oakland A’s – 11-45- .196 as of Tuesday morning -- might break that record. A lot of people who love the Mets are rooting for Oakland to somehow avoid a new low, and leave that honor to Casey Stengel’s 1962 Amazin’ Mets. Is that twisted? Not from my point of view. The 1962 season remains memorable – the first season for an expansion franchise created to replace the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants, who had bolted to California in 1958. The Mets were often terrible, but they were also a lot of fun, with Stengel diverting attention from all those losses. Now, 61 years later, many Mets’ fans – and also some vintage Mets players -- are saying they could easily live with that distinction. “Keep the record!!!” texted Bill Wakefield, who had a decent year as a reliever in 1964. “I want that to be forever,” says Howie Rose, the Queens kid living out the dream by broadcasting Mets games on the radio. He will be honored by the Mets Wednesday evening and will throw out the first pitch – as fans display their Howie Rose bobblehead dolls. Rose goes back to 1962 when he was 8 years old and his father took him to the Polo Grounds to see the new team. “Being a narcissistic kid, I thought it was all for me,” Rose told me over the phone on Monday. The Mets beat the Cardinals and Gil Hodges hit what turned out to be his last home run. Rod Kanehl – the scrappy minor-leaguer who came to be a folk hero of the early Mets – hit the first grand-slam homer in Met history! Complete game by Roger Craig! Felix Mantilla 4-for-4! My man Joe Christopher playing center field! “It was a year-long celebration,” Rose said, noting that the Mets somehow won a World Series only seven years later. Amazing. “You had to be there,” Rose said. Craig Anderson was there at the start – a Lehigh College graduate, obtained from the Cardinal organization, one of the many “university men” that Casey and Edna Stengel relished. Anderson was the winning pitcher in both ends of a doubleheader against the Milwaukee Braves, raising the Mets’ record to 12-19. Maybe they were not so terrible, some people said. They promptly lost 17 straight, and finished the season at .250. Anderson was up and down with the Mets the next two years, and ended his major-league career with 19 consecutive losses – which was the record going into the 1992 season when another Met, Anthony Young, kept losing. “When Anthony Young approached my 19 straight losses,” Anderson texted Monday, “I wrote him and said I hoped he did not break my record, to no avail. He had good stuff and bad luck. I did the best I could but lost some starts when relievers failed me. So that’s baseball…” Anthony wound up losing 27 straight decisions with the Mets and Cubs, and died in 2017. Craig Anderson, 84, watches the Oakland Athletics stumble, as the A’s ownership allows the franchise to dwindle, to make it easier to get out of town, to Las Vegas. (And why not, given MLB’s dangerous new flirtation with sports gambling?) Some people would welcome another team breaking the Mets’ 1962 record. Keith Hernandez, who helped win World Series for St. Louis and the Mets, said on a TV broadcast last week that the Mets and their fans should be glad to get rid of the streak. But Craig Anderson is not so sure. He took heart from the old-timers’ day in Queens last summer, a lavish reunion including a few original Mets. Anderson added: “Don't forget a truly professional man, Gil Hodges, on and off the field!” “After the recognition that my teammates and I received last August, I truly feel about playing on the first Mets team was a special moment in my career,” Anderson continued, saying his team was “a small part of baseball history and Mets fans made us feel special too. “So let our record stand. Mets fans proved to me that former players, win or lose, are still special” -- Craig Anderson, 1962 Original Met, and Proud of It.” ### Let me start by saying Babe Ruth is my favorite athlete, all-time.

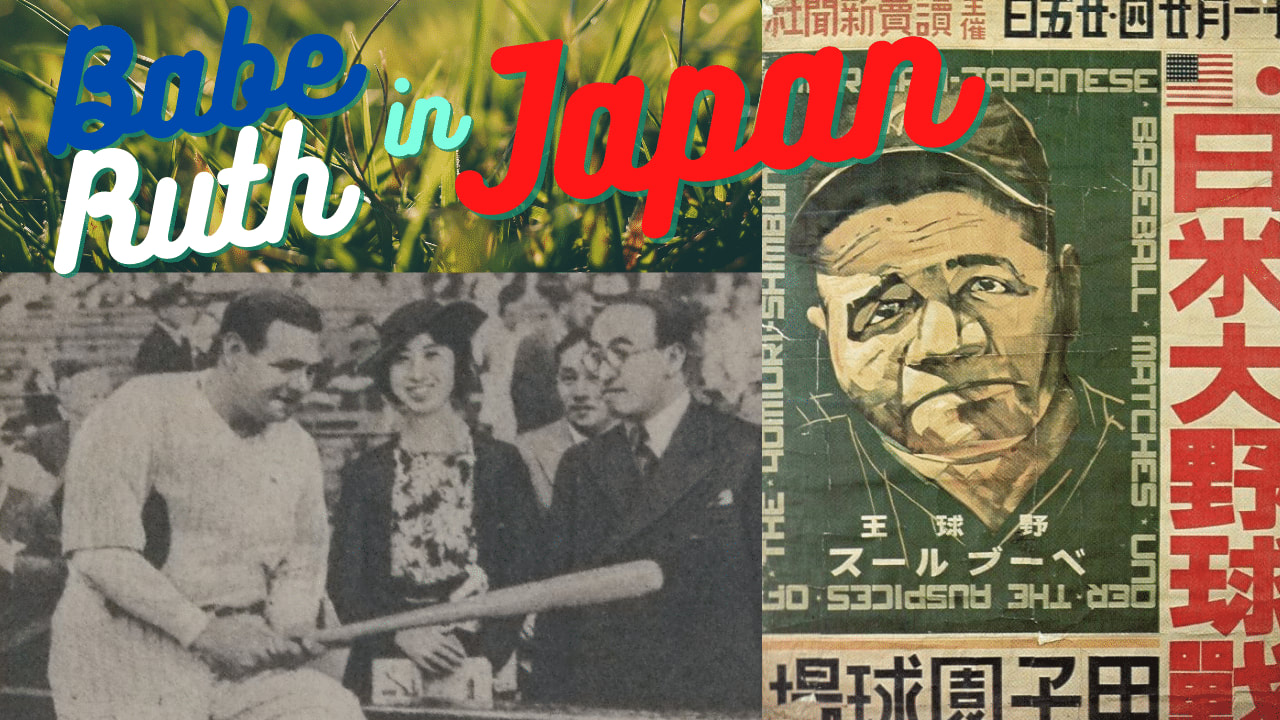

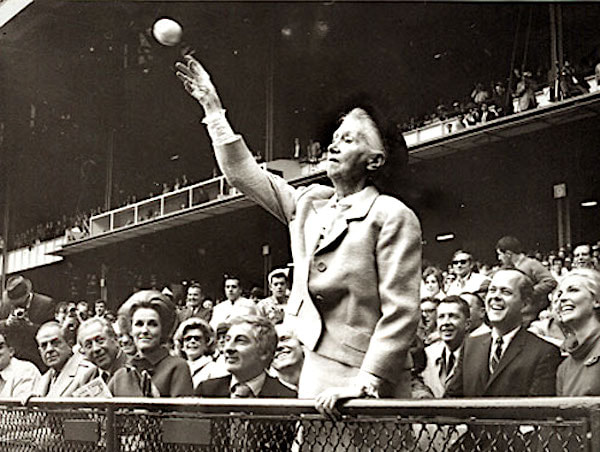

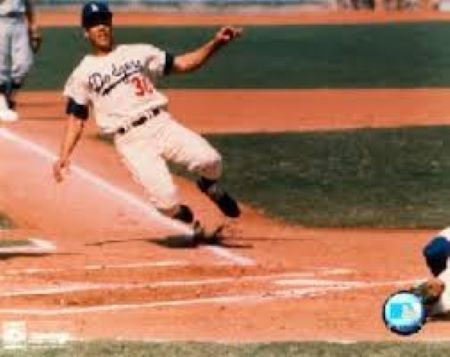

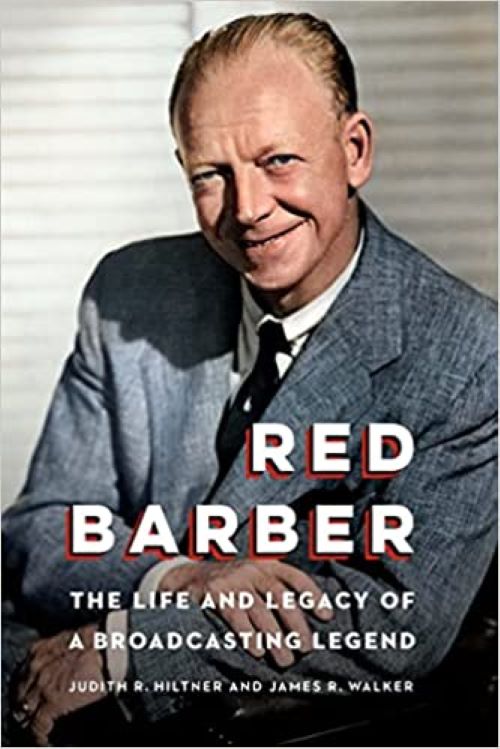

Not just because I witnessed him, last game of 1947, clearly sick, addressing a crowd in Yankee Stadium. Not just because he had coached for my Brooklyn Dodgers for a while. Not just because I later met his daughter who talked about “Daddy.” I consider him my favorite athlete because he could pitch and he could hit and he could entertain fans just by being “The Babe.” Now I can say, I have also seen Shohei Ohtani pitch and hit in the same game, for the World Baseball Classic, holding off the Americans with skill and power and flair, just like the Babe. Whatever else is wrong with the world at the moment – don’t get me started – there is this versatile champion from Japan, thrilling fans around the world. By now, you undoubtedly know that Ohtani saved Japan’s victory over the United States late Tuesday evening (Eastern time), closing the game by striking out his Los Angeles Angels teammate, Mike Trout, with a hellacious slider that broke clear across the plate. If there is anything you don’t already know about Tuesday’s championship, try to log on to Tyler Kepner’s column in the Times, written right after the game. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/22/sports/baseball/shohei-ohtani-world-baseball-classic.html Tyler touched all the bases, with gusto and knowledge, writing: “ The tournament, it is safe to say, is no longer taking off. It is already in orbit.” The Babe, it is said, saved baseball by hitting more home runs than anybody had ever done, 29, while still a starting pitcher for the Boston Red Sox in 1919. In the same year, some members of the Chicago White Sox conspired to lose the so-called World Series, in a gambling plot, followed by sleazy legal maneuvers by the hangin’ jury of the baseball leadership. The Yankees purchased Ruth, who promptly hit 54 home runs and entertained the world (including Japan, on a barnstorming visit) for a decade and a half. Now, Shohei Ohtani has pushed the baseball tournament toward the grand tournament for the world’s most popular sport, soccer/football, the World Cup. In its own quadrennial tournament last fall, Argentina’s elder superstar Lionel Messi held off France’s young superstar Kylian Mbappé in an exciting final. Baseball still has a long way to go, around the world, but at least Ohtani has nudged his sport into the discussion of world events. Ohtani made baseball a 24-hour spectacle. I confess, as a notorious early bird, that I have rarely caught a glimpse of Ohtani (or, for that matter, Mike Trout.) I’m a Mets guy, a National League guy. But now Ohtani, with one inning of smoke, has inserted himself into worldwide consciousness. I woke up Wednesday morning and found an email from our friend Fumio, who used to live across the street on Long Island – such nice people, I think of him and Akie every day. back home in Japan. I replied to Fumio that as a baseball fan and a journalist, I recognized that the “story” was this poised young superstar holding off his Angels teammate and the American all-stars. It is now 105 years since Babe Ruth pitched and hit the Red Sox to a “world” championship. Imagine. One hundred and five years. An accomplishment I can legitimately label “Ruthian.” A week ago, I wrote about a terrific new biography of Jim Thorpe, by David Maraniss. I was particularly tantalized to read that the great American athlete, while at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, had been friendly with a young teacher named Marianne Moore. Yes, exactly, the same Marianne Moore who soon moved to Brooklyn and became a famous American poet into very old age. Finding Miss Moore in a Thorpe biography touched off my recollection that in 1968 the worldly president of the New York Yankees, Michael Burke (whom I miss to this day), invited her to throw out the first ball on opening day. The mention of Marianne Moore also touched the heart of the writer, Sam Toperoff, who has been my friend and inspiration since he was a basketball player/scholar at Hofstra College in the late 1950s. Within 24 hours, I received Sam's email from the Hautes-Alpes department of France, containing references to two poets who won Pulitzer Prizes, 49 years apart – Marianne Moore (1952) and our friend Stephen Dunn (2001.) Sam wrote: “Dear George—After my first book came out, I got a call from the editor to tell me Marianne Moore loved it and wanted to talk with me about it. She invited Faith and me to tea on a sunny Sunday. She lived in a brownstone downtown, very near the Tombs. The fall of 1965, I think. She was, when she opened the door, indeed Marianne Moore, the old lady whose poetry I had studied as a student and taught as a professor at Hofstra. “Yes, I was intimidated. But the editor had told me she wanted to meet me because she thought me very brave to have endured all I had written about in my book when in fact for me it was just a normal accounting of my lower middle-class family life as I had lived it up to that point.” (NB: Sam’s first book was “All the Advantages,” circa 1965, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize by the Atlantic Monthly Press.) Sam recalled how Miss Moore “served tea and cookies she had baked herself. Marianne Moore! All was sort of stiff and formal until somehow the subject of baseball came up — I knew from her poetry she loved the game. Then she went off on the Dodgers. Remember, she had spent most of her writing life in Brooklyn; she had just moved to Manhattan. Well! She loved Pee Wee Reese, spoke poetically about him, how he glided, how effortlessly he played, how good he was for Jackie. Marianne Moore! She also lauded Red Barber for making her life so rich in her Brooklyn apartment. That was mostly what we talked about with Miss Moore that long afternoon — the Brooklyn Dodgers! “I signed my book for her; she signed her last collection for me. And we went home. Her volume sits on my shelf next to Stephen Dunn.” Before Stephen Dunn became a poet, he was a zone-busting jump-shooter teammate of Sam, who, on long bus rides into the wilds of Pennsylvania, encouraged Stephen to use the rest of his brain. My college athlete pals (I was the student publicist) followed Stephen’s fame and also his terrible battle with parkinson’s disease, which rendered him unable to recite his own work in later years, although he wrote to the end. Sam wrote: “As Steve was dying — I only thought he was ailing, damn it — he sent me a poem called ‘Final Bow.’ That’s when I got the message. Then when his collection came out, this was the poem he used to say goodbye, so he had orchestrated his own exit, the son-of-a-bitch. It’s a superb and funny and serious poem. “Hell, why don’t I type it, forgive me if I cry:” Final Bow In my sleep last night When the small world of everyone Who’s mattered in my life Showed up to help me die, I mustered the strength To rise and bow to them A conductor’s bow, that deep Bending at the waist, right arm across my stomach, the left behind my back. At first it seemed like the comedy of aging had revised and old scene-- how, with time running out, I’d make the winning shot In my schoolyard of dreams, Only now I was wearing an unheroic gown, apparently willing to look foolish-- for what? What no longer mattered?-- before I lay again down. ---Stephen Dunn, 2021 Sam wrote: “I take that last poem of his as something of a challenge: How to go out the right way.” Stephen died on his 82nd birthday in 2021. Sam added: “And yes, I did cry. I love this poem. I love him, his talent, his courage, his exit.” Larry Merchant writes, in the good old New York Post, about Marianne Moore:

https://storyoftheweek.loa.org/2019/10/poetry-in-motion.html It's bad enough that Baseball Commissioner Rob (Roll ‘Em) Manfred has brought about a sleazy era of gambling on the sport that has banned Pete Rose for life.

Baseball is also the former holier-than-thou business that banned Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle for fronting for gambling dens after their retirement. They were reinstated, but then Rose got busted for life for violating gambling rules. Nowadays baseball runs blatantly insulting commercials of young males displaying their insecurities by betting on sports events. Some hitter in a distant ballpark smacks a double off the wall and the young man leaps from his chair, as if he himself hit the damn ball. Encouraging gambling is Rob Manfred’s game, and maybe Steven A. Cohen’s world, on deck. The Mets’ owner is pushing to see if he can get away with building a gambling den a dice throw away the ball park named after a bank. Cohen has been an activist owner since taking over the Mets – getting rid of a lot of deadwood in the organization and spending millions upon millions for better players plus activists like Billy Eppler and Buck Showalter. Those are the current conditions, and Cohen spends and spends. (He also showed great showman instincts by staging two of the best feelgood events I’ve ever seen in a ballpark – the retirement of the No. 17 of Keith Hernandez, and reviving the Old Timers’ Game and festivities, including a dying John Stearns, and survivors of Mets’ stalwarts Tommie Agee, Alvin Jackson and Bill Robinson. Events like these do not just happen. They take money, and staff, and good instincts on the part of the still-new owner. One suspects Cohen will even go ahead and sign Carlos Correa, unless Correa truly has a lead leg. Cohen is no fool. He avoided getting stung by over-paying for the five-innings-a-week pitcher, Jacob deGrom, despite the grand memories of when deGrom was healthy. (As for deGrom’s cold-blooded “I’m rich! I’m rich!” smile when he bolted from the Mets with nary a kind word about the good times in Flushing: As we say in Queens, Yeccch!) Cohen understands the process of making more and more money. He has noticed the bleak concrete emptiness of parking lots -- “50 acres of asphalt" -- to the west of New Shea Stadium, and he has envisioned late-model cars bringing lucky tigers escorting handsome women, with money to burn. Or at least, that is the image. Fortunately, the governments of New York city and state still have a chance to veto a gambling den on very public land. (Wait, don’t Mets fans park their cars there 81 home games a year? Isn’t traffic bad enough in that tangled sector?) According to the Wall Street Journal, Cohen held an open house for interested Queens types the other day. No fool, Steven A. Cohen. He played down the lust for a gambling den by saying he just wanted to hear the opinion of the Queens folks – known for their cagey urban instincts (sussing out the criminality and bullying of former Queens resident Donald Trump.) At the open house, my Queens homeys seemed to voice a skeptical attitude toward the gambling den. According to the WSJ, the folks who showed up – for a ballpark frank! – voiced preference for live music, dining, art exhibits and festivals rather than gambling. The WSJ reported that Laura Shepard, a community organizer for the transit advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, told Cohen that the development should be a destination that people can walk, bike or take transit to — not just drive. “Personally, I don’t want to see the casino,” she said. “Most people want more green space, concerts and community events.” There is a lot of communal pride in Flushing-Corona-Jackson Heights-Forest Hills swath of Queens, home to a hundred languages and food tastes. This is the same region that fought back an attempt to build a soccer stadium on the crowded public fields of Flushing Meadows park a couple of decades ago. A big-time soccer stadium will soon be built where the chop shops once hunkered. Isn’t that enough upgrade for anybody? The locals should tell Cohen and Manfred: Go gamble somewhere else. Go to Atlantic City, that once bled the great businessman Donald J. Trump. Go to hilly Connecticut where white marauders once slaughtered Indigenous people near the site of today’s Foxwoods -- tainted grounds, now packed with roulette wheels and poker tables and sporty folks. Here’s one idea for Stephen Cohen’s “50 acres of asphalt:” Mara Gay of the New York Times recently wrote: “More and more, living in New York is out of reach not just for working-class or middle-class residents but nearly anyone without a trust fund.” I bet Steven Cohen could make a few bucks from something actually needed, like moderate-cost housing. Then, there is this. One of the great New York City treasures of recent decades – an Irish/baseball pub, if you can imagine, named for a gremlin sportswriter, Red Foley – had a trove of baseball souvenirs covering every inch of wall and ceiling across the street from the Empire State Building. But the pandemic forced the proprietor, Shaun Clancy, to close down (paying his workers for at least a month, out of heart.) Shaun is now cooking at a refuge for the homeless on the Gulf Coast of Florida; he chats up the weary while doling out something filling and maybe even healthy. I bet you – pardon the expression – that if Steven A. Cohen erected a Foley’s II on the ”50 acres of asphalt,” Shaun would dust his vast souvenirs from its storage place, and oversee a renaissance of Foley’s II. And patrons could teeter discreetly to the 7 Line or the LIRR station, staying off the highways. Win-win. Steven A. Cohen, meet Shaun Clancy. (Sept. 6: When the glorious season went downhill) What can you say about a baseball team that died? That it was talented and spirited. That it played with vestiges of old-timey baseball. That it had Edwin Diaz jogging in from the bullpen, accompanied by Timmy Trumpet. That it ran out of gas in the final month.* From spring training to Labor Day, the Mets found ways to win, sometimes with power, sometimes with guile and bunts, sometimes despite two iconic pitchers showing signs of mortality. Mets fans reassured each other that this was one of those rare seasons in the team’s torturous history. Buck Showalter, glowering in the dugout, had all the information in his meticulous, finicky mind, in his little black notepad. In the second half of the season, the Atlanta Braves asserted themselves (“They are the World Champions,” Good Old Howie Rose said on the radio recently.) There are theories about why the Mets fell apart. The pitchers caught up with Pete Alonso and Francisco Lindor. Not enough power from the two catchers. The late-season acquisitions were exposed. (Tired of watching Daniel Vogelbach take third strikes?) DeGrom and Scherzer could not pitch late into games. The “organization” showed mixed messages in bringing up three callow prospects late in the season, without time to adjust to the majors. But I’ll tell you the worst thing to happen to the Mets in 2022:, when a record-setting 122 Mets hitters were hit by pitches. The worst was when Starling Marte was whacked on his right hand on Sept. 6. Marte was the soul of the Mets, a refugee from the lower depths of the majors, with an athletic strut, a knowing smile, the ability to steal a base, hit a homer, bounce against the wall to make a catch. I always liked him with the Pirates. With the swagger of Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the late heavyweight champion, Marte was always on the move, connecting with fans, perpetual motion. But Marte did not play until the wild-card series, a full month later -- stealing a base or bouncing into the outfield wall, with a splint on his aching right middle finger. By the time Marte got back, the Mets’ fire was gone. The final month was sour, particularly in the three wild-card games. ---When Max Scherzer was bombarded for four homers in the opening game, a lot of Mets fans -- so colorful, so verbal, so passionate -- took the low road with yowls and boos for Scherzer. Shame on them. I bet St. Louis fans didn’t boo anybody as the Cardinals went down and out, at home. --- In the Mets' third and final game with the Padres, while Joe Musgrove was mowing down the Mets, Showalter asked the umpires to check him for a foreign substance on face or uniform. The umpires poked at Musgrove’s ears, which only made Musgrove even more resolute, as he pitched seven innings, giving up one hit. I’ve known Showalter since his first days as Yankee manager, and I get a kick out of him and his old-school game tactics. But Showalter’s ploy against Musgrove looked cheesy. So the Mets’ season is over. No point in looking ahead. The three lead pitchers were wobbly in crucial series. Some contracts are up. The “prospects” never did get enough experience to show what they might do next year. But Mets fans have their memories – Nimmo’s catch, Escobar’s torrid September, McNeil’s batting title, gallant slides home, swarms on game-ending hits, and most of all, the trumpets for Edwin Diaz, now echoing in the Mets' empty ball park. With all due respect to the other baseball team in New York, and the classy slugger, Aaron Judge, for this worn-down Mets fan, it is now time for the old Brooklyn saying: "Wait til next year." --- * With homage to Erich Segal, author of "Love Story" This is why I love baseball: No matter how hard the new analytics types try to invent a new sport, the ashes of the old game, the real game, spark into flames again. On the day before Maury Wills passed, a current major-league player performed some derring-do worthy of the old master. Terrance Jamar Gore is not dashing into the Hall of Fame or even a steady spot on a major-league roster. But when a contending team needs what sports broadcasters like to call “foot speed,” plus “smarts,” Gore is often hailed from the minor leagues to bedevil pitchers, catchers and whoever is supposed to be covering the next base. Maury Wills did the bedeviling on a daily basis for 14 major-league seasons, winning three World Series for the Los Angeles Dodgers. His life – the ups, the downs – was described by Rich Goldstein in the NYT on Tuesday. Before I get to Terrance Gore, Wills’ spiritual descendant, I will share two visions of Wills: ---At the peak of his career as brilliant leadoff man for the light-hitting but championship Dodgers, Wills threw his smallish body at the next base and its surrounding dirt paths – enough to incur red abrasions, known in the trade as “strawberries,” on his hips. The off-season was not long enough to heal them, so by the following March Wills would be grinding his skin all over again. (Some old-timers wore sliding pads inside their uniforms but Wills and other players preferred uniforms tailored for their slight builds, hence perpetual strawberries.) ---Wills did not merely steal bases. He borrowed baseball wisdom from ancients like Casey Stengel, when the Old Man managed the new team in New York in 1962. I cannot pin down when and where this happened, but I heard about it since 1962: Casey was giving a pre-game sermon to some Mets about the value of the “butcher boy” – slashing the ball downward, better than a bunt. The Mets seemed bored by the lecture but Casey noted one astute pair of eyes belonging to Maurice Morning Wills, the Dodgers’ shortstop, at the edge of the circle. The Old Professor was happy to have one student. So that was Maury Wills. Baseball has since evolved into a perpetual home-run derby, with would-be sluggers armed by details like “launch angles” and “exit speed.” Speaking of home runs, both New York teams had long-ball frolics Tuesday evening—Aaron Judge hitting No. 60 and Giancarlo Stanton hitting a walk-off grand-slam homer for, yes, you got it, the Bronx Bombers, and the Mets coming back from a 4-0 deficit on a 3-run blast by Pete Alonso and a grand-slam by Francisco Lindor. Quite a night for “exit speed.” Before that, the Mets won a game last Sunday on the legs and wits of Terrance Gore, all 5 feet, 7 inches and 160 pounds of him. Gore is 31 and with a ball cap on his head he looks half that age. He has a .217 major-league batting average, higher than that of some lugs lunging at every pitch. He is a stolen-base specialist, used in vital circumstances in big games, and already has three World Series rings and would not mind running and sliding the Mets into this year’s Series. The Mets picked him up from the minors in August, and he got into the tie game when Tomas Nido led off the eighth inning with a single. Everybody knew why Gore was out there. The pitcher threw several times to first base to keep him close, but Gore confidently edged back onto the dirt basepath, busting for second as soon as the pitcher threw home. The catcher’s throw flew into center field and Gore scrambled up and darted to third, and he scored the tie-breaking run on a single by Brandon Nimmo. Home runs are fine. But even with the gigantic pitching staffs of today, the game should have room for a running specialist. And if you are not yet charmed by the concept of the running specialist, ladies and gentlemen, the professional pride and knowledge of Mr. Terrance Jamar Gore: Not all the old-timers wore uniforms at the grand celebration of antiquity. The old players, legends all, visited Queens on Saturday as the tradition of Old-Timers’ Day was honored after a gaping absence of 28 years. How wonderful it was to sit in my home cave and watch Frank Thomas, Jay Hook, Ken McKenzie and Craig Anderson from the first team in1962. They were good people then, helping Casey Stengel create the lovable myth of the Amazin’ Mets. Now, in the very young and very promising era of the new owner, Steven Cohen, the Mets brought back 60 old-timers to stand in for the Richie Ashburns and Alvin Jacksons who toiled so honorably in 1962. Wonderful touch: room on the field for family members representing Gil Hodges, Tommie Agee, Willie Mays and my departed friend, 1986 coach, Bill Robinson.  Steve Jacobson and Mookie Wilson Steve Jacobson and Mookie Wilson Mingling with the old-timers was my friend Steve Jacobson who helped cover the first season for Newsday and starred as columnist for decades. Steve, going on 89, was welcomed by Jay Horwitz, the haimish maestro of Mets alumni affairs, who also invited me as a surviving veteran of 1962. But I’m still ducking public gatherings during the pandemic, so I stayed home and waited for Steve to call me with the gossip. Steve said he wished he could have chatted with all of them, but there was such a crush, everywhere. He could have talked to Frank Thomas about hitting 34 homers and driving in 94 runs, and Ken McKenzie, who had the only winning record (5-4), and Craig Anderson, who won both ends of a May doubleheader over the Milwaukee Braves to raise the Mets’ record to 12-19 and cause manager Bobby Bragan to call the Polo Grounds a “chamber of horrors.” Oh, yeah. The Mets promptly lost 17 straight, en route to a 40-120 record. Steve also could have talked to Jay Hook, with his engineering degree, who won a game one day and told the writers it was like eating sour cherries but then tasting a sweet cherry. (All three 1962 pitchers present Saturday were part of Casey’s respected “University Men” – McKenzie from Yale, Anderson from Lehigh and Hook from Northwestern.)  Steve Jacobson and Ron Swoboda Steve Jacobson and Ron Swoboda Steve did have time to mingle on the field, wearing a Newsday ball cap, with his wife, Anita, snapping photos of him with epic Mets including Ron Swoboda and Mookie Wilson (who later would gambol in the outfield in the old-timers’ game, along with another sleek alum, Endy Chavez.) The part that Steve treasured most was having a few old Mets tell him he had been one of those sportswriters who did not throw them under the bus when they had a bad hour on the field. We were reporters, we were critics, but we were not rippers. Now the Mets are in a new era. Steven Cohen, a grown-up Mets fan, used his money to hire Billy Eppler, Buck Showalter, Francisco Lindor and Max Scherzer. Who knows if the Mets will hold off the Braves and go far in the post-season? But gestures like the recent Keith Hernandez number-retirement and Willie Mays number retirement (honoring the jolly first owner, Joan Whitney Payson, indicate a generosity of pocketbook and heart. (Speaking of not throwing people under the bus: a few old players and writers and fans have blasted the previous ownership of Fred Wilpon and Saul Katz for not putting enough money into the franchise. I have a friend who ran a center called Abilities, Inc., on Long Island, which helps people function better in work and social life. I am told that the Wilpon-Katz family was generous with money and energy.)

Let's just say: the Mets are in a new era. I was happy to hear my friend Steve Jacobson bubble about his hours back at the ball park with similarly elderly Mets who once upon a time gave the fans so many memories -- some of them even good. We all need a momentary diversion from the 10 or 12 top terrors loose in the world.

The Mets do it for me -- playing a brand of ball I thought had gone out of style. As of Monday morning, they were tied with the Yankees for the best record in baseball. Nothing like big-market money. I think of all the years when I worked at appearing professionally neutral. Now that I am retired, I am free to watch the Mets – with two separate Met-centric smartphone message dialogues going at the same time. The Mets are so much fun to watch because they are defying the launch-angle, exit-velocity analytics trend that has rendered contemporary baseball so stultifying. It can be done. The Mets of recent years had the same bad habits of other teams – trying to put the ball over the fence and get their moon shots on TV and social media. Managers came and went – good grief, one general manager was a reforming player agent -- but New York money-guy Steve Cohen bought the team and brought in Billy Eppler as general manager and hired Buck Showalter as manager and now the Mets hitters are humbling teams with their lopsided shifts, hitting it where they ain’t, in the immortal phrase of Wee Willie Keeler. Jeff McNeil once was lost but now he’s found – propelling a home run now and then, when it comes naturally, with his good swing. Showalter is doing one of the most noticeably great managing jobs I have seen in a long time. I’m happy for him. Met him the winter before he took over the Yankees, a boy manager who had impressed Billy Martin with his knowledge as a fringe coach during spring training. Now he was getting his chance. I flew into Pensacola one morning in mid-February of 1992 and he drove me to his old neighborhood, more Alabama than Florida, introduced me to his pals at the gas station, in a town where his late father, a former Little All-American fullback and a high school principal-coach, was a legend, and then we stopped off to meet his mom. Ever after, when I was around his team, Buck he would point to me and say, “There’s George, he’s been to my hometown, he understands.” I wasn’t always sure what I understood, but, sure, Buck, sure. These days, he is a master at work in his dugout, intense, obsessive, usually with bench coach Glenn Sherlock at his side, as a sounding board. Have you ever seen coaches more alert, more pro-active, than Wayne Kirby (social director at first base), Joey Cora (performing acrobatics at third base), Eric Chavez (hitting coach, smiling reassuringly in the dugout) and Jeremy Hefner, (pitching coach, foxlike, alert to every nuance of his charges?) During the game, Showalter conducts little seminars with lifers like Max Scherzer and Francisco Lindor, while popping sunflower seeds into his mouth and making snarky comments to the umpires. Old school. Buck neglects nobody. He gets players into the lineup, before they get too rusty. He benched Mark Canha for a few days after the Mets spent more of Steve Cohen’s money for Tyler Naquin, and on Sunday Buck put Canha back in the lineup, and of course the pro responded. And for those hard-core fans, who spend their hot summer days and nights peering at the tube, it’s been a pleasure to watch the pitchers holding the Mets together when Scherzer was hurt, when Jacob deGrom was recuperating. The past week, those two aces have been back, as good as ever. Buck tried to nurse deGrom through the sixth inning on Sunday until Dansby Swanson broke up the no-hitter with a two-run homer and Buck nodded and gave deGrom the rest of the day off. It is a memorable season for Edwin Diaz, reviled in his first season in town, now having the best relief season ever seen – entering to the stirring trumpet music. On Friday Showalter recognized this was August, and they were playing the Braves, so he asked Diaz to pitch two innings and received six outs of Koufaxian brilliance. Luis Guillorme – once known primarily for having caught a wayward bat (the baseball kind) in the dugout – has been so good that Buck uses him in most days. day. Along with the Diaz entrance, the best show on the Mets is Guillorme and Lindor playing Marquis Haynes and Goose Tatum (ask your grandfather) with the ball as they trot off the field at the end of an inning. And I haven’t even mentioned Pete Alonso…or Starling Marte….or Brandon Nimmo…the other pitchers. (I am also taken with Carlos Carrasco, and his El Greco-painting serenity.) Entire odes could be written about the Mets -- and sometimes are, on our smartphone links-- during this compelling season that gives us a rest from all the other stuff. Suzyn Waldman speaks Bostonese. Chris Russo speaks Rabid Canine. Congratulations to both icons of the New York ear (and head, and heart) who have just been voted into the Radio Hall of Fame. Their endurance has demonstrated the power of the spoken (or sung) word, for people driving a car or working out or just lazing in a chair. Radio lives. And Suzyn Waldman and Chris Russo have endured for decades, from their early days on WFAN. Waldman is the radio compañera of John Sterling, the long-time play-by-play mainstay of Yankee games. Sterling, bless his heart, provides shtick and nicknames and operatic exaggeration to back up his long career of calling games. Suzyn Waldman (from Newton, Mass., and Simmons College; but you could hear that) had an earlier career in musicals – most notably playing Dulcinea in “Man of La Mancha.” Then she gravitated to talking about sports and was hired by WFAN. Was she a novelty act? She blew up that stereotype by doing what the best reporters do, on any beat. She hung out. She asked questions. And she won the respect of players, managers, coaches and the informed beat writers. From her time in the clubhouse, she knew what player was favoring a sore leg, or was in the doghouse, or had a weakness for a slider. The listener came to rely on her commentary, always politely but authoritatively following Sterling’s calls. Plus, she can follow the fickle bounces in distant corners of a stadium. Yankee fans soon realized: Suzyn Waldman knows her stuff. Not only that, but Waldman became such a moral force that she brokered a reunion between George Steinbrenner and Yogi Berra, who rightfully harbored a grudge against The Boss for having fired him. Blessed are the peacemakers, like Suzyn Waldman. Christopher Russo materialized as a sports reporter on the radio spectacle called “Imus in the Morning” – dominated by the equally brilliant and vicious Don Imus. Your ear could not miss Russo’s babbling patter that resembled Daffy Duck in the cartoons. When the station morphed into all-sports WFAN, he was paired with the opinionated Mike Francesa. (Imus called Francesa and Russo “Fatso and Froot Loops.”) In 1991, I wrote a column about Russo in which I unearthed his secret life: his mom came from England and was reportedly horrified by his diction; he had attended colleges in three different countries – England, Australia and the U.S., and before that he had attended a private school in New York State. Away from the live microphone, I detected a pleasant, centered, educated and ambitious kid who had taken speech therapy and did not mind admitting it. My headline (columnists got to write their own headlines in those days) was: “Mad Dog Is a Preppie.” He and Francesa were wired, babbling about game strategies the night before or pending trades or players who had popped off; I will admit there were times when I needed to see if the odd couple could flush out an owner or a commissioner or an agent. Nobody wanted to be hectored by Mike and the Mad Dog. It was compelling radio, in its way, as long as they lasted together. These days Russo is on Sirius. Sorry, a lot of new things like Sirius and podcasts are outer space to me. I’m a child of radio. I can still remember Edward R. Murrow scaring the hell out of me with his war dispatches from London when I was 4 and 5, and when we managed to survive that war, I found Arthur Godfrey’s jovial variety shows and Red Barber’s erudite calls of the sainted Brooklyn Dodgers. I discovered music on the radio – from Crosby and Sinatra to Aretha and Bob Marley and The Band and Dolly Parton, disk jockeys from the long-ago Jack Lacy on WINS-AM to William B. Williams on WNEW-AM (until I heard him destroying a vinyl record, live, on the air, by some new shaggy-haired kids from Liverpool.) Radio: Garrison Keillor, NPR, Jonathan Schwartz and Peter Fornatale on WNEW-FM, the doomed classical station WNCN, and nowadays an upgraded WQXR-FM particularly Terrance McKnight from Morehouse, 7-11 PM weeknights, the eclectic John Schaefer on WNYC and the great interviewer Brian Lehrer, WNYC, both AM and FM. Baseball? It was invented for the radio, or vice versa, never more than when the grubby forces of Major League Baseball condemn Mets or Yankee games to other networks. Radio is a vibrant medium, all on its own – and Suzyn Waldman and Chris Russo are deservedly in the Radio Hall of Fame. Ever since Roger Angell passed last week, friends have been e-mailing about how great he was, and asking how well I knew him.