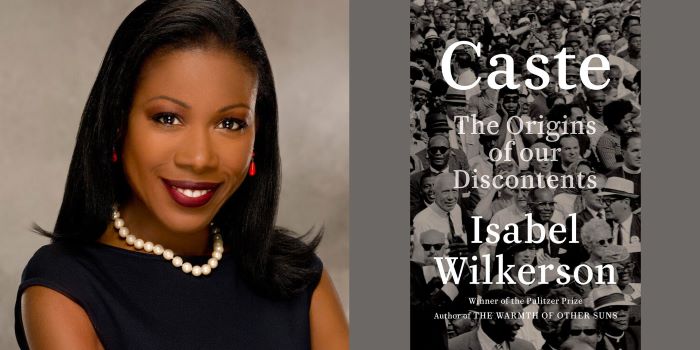

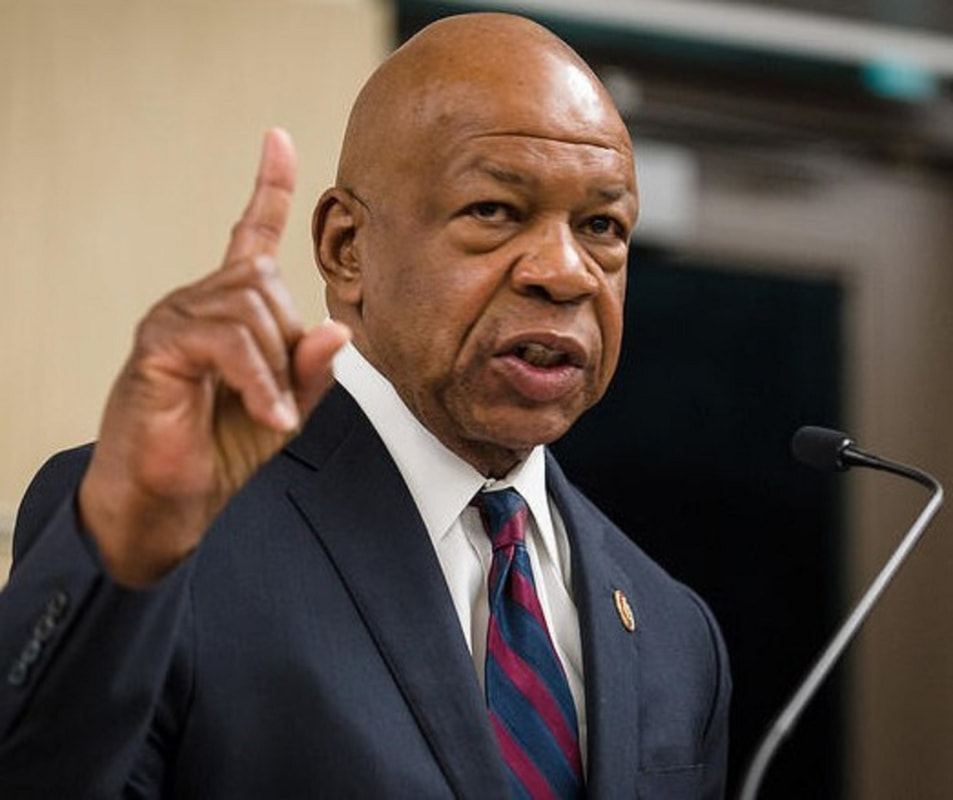

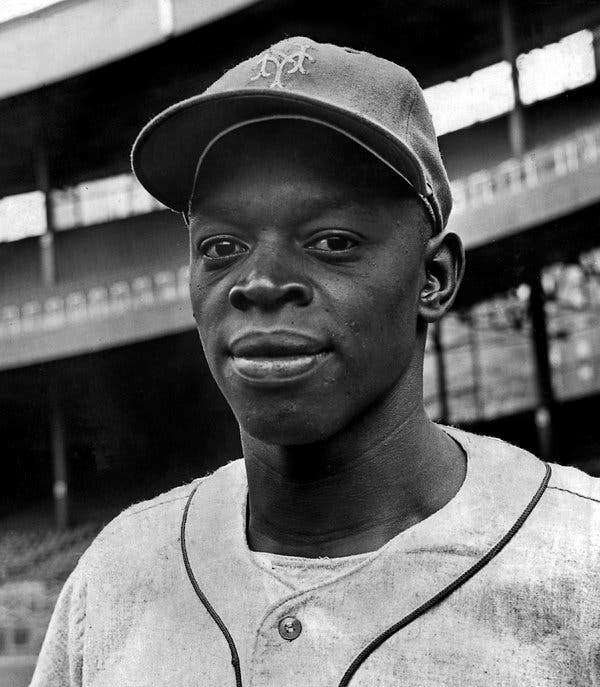

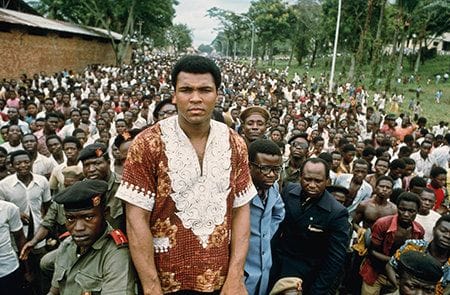

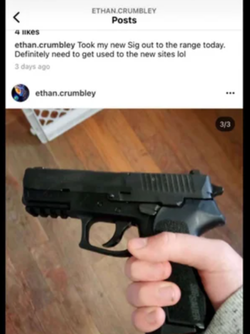

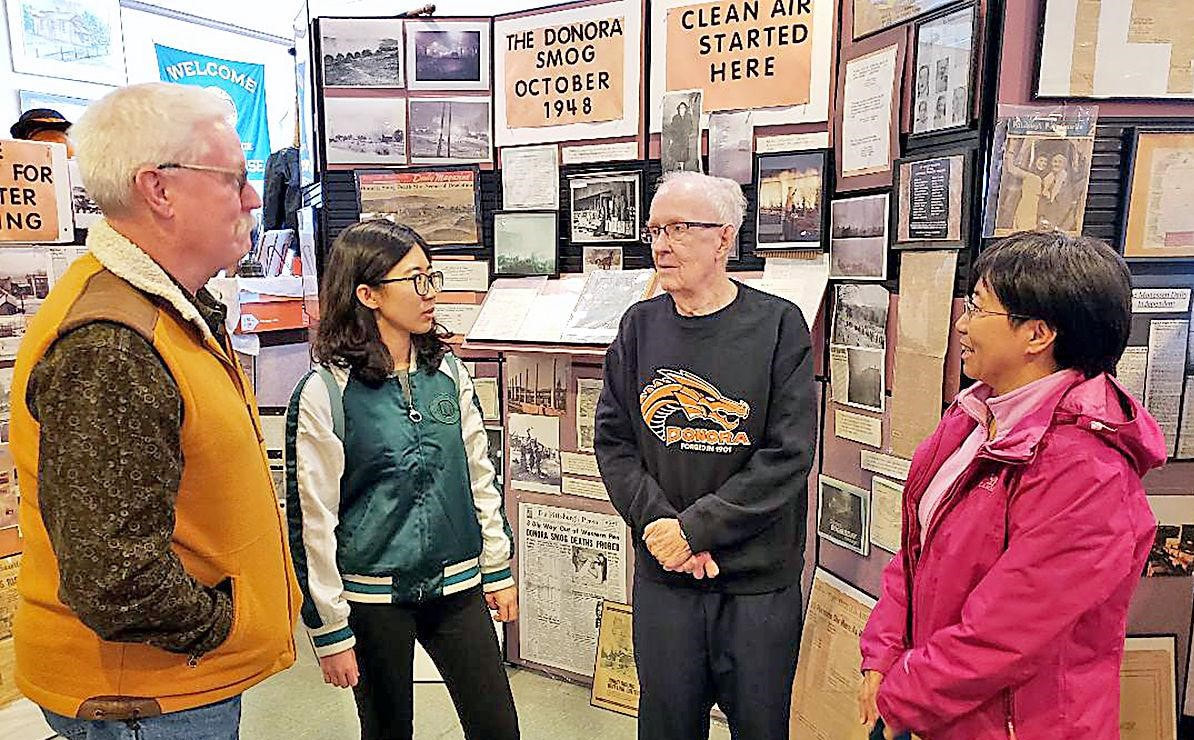

Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Here on the Manhasset-Port Washington tectonic plate (if there is such a thing), some people still feel the rumbling from Jim Brown, local guy, who died Friday at 87. They remember the earth trembling when Brown crashed into opponents in most of his five sports. (Correct: five sports.) They also remember the impact of his loyalty, when he chose to come home to Long Island. Brown was many things to many people (including a felon serving a few months for misbehavior toward women.) Bad side and all, Brown was surely an epic figure out of ancient legends – from Beowolf to Babe the Blue Ox to John Henry, the steel-drivin’ man. Some people remember, first-hand. I called my pal and neighbor, Paul Nuzzolese, who played three sports at Schreiber High in Port Washington. Paul’s family used to run a visible ice-and-wood business with trucks rumbling all over the metropolitan area. Paul played guard in football, was on the basketball team, and was a lefty pitcher on the Port baseball team. The plan for Jim Brown was to throw off-speed, not give the big guy something he could hit. And if you could induce Brown to chop a grounder, it was wise to avoid a collision. Were baseball opponents intimidated by the sight of Jim Brown on the basepath? Paul called me back Sunday morning after he recalled pitching at home against Manhasset, and being taken out when the game was tied after a regulation seven innings. That gave him a good view of Brown's 360-foot perambulation of the bases: "Brown hit a squibbler down the first-line," Nuzzolese said. "You know how hard it is to field a squibbler." Harder with fully-grown Jim Brown hustling down the basepath. (No names mentioned of the Port fielders.) The ball got past the first baseman, into right field, and Brown took off for second, and continued toward third. The Port third baseman waited for the throw, but was wary of Brown barrelling down on him, and needless to say Brown wound up scoring on the aforementioned squibbler. Port lost the game, but the fielders retained their knees, and their wits. Still, like Jim Thorpe and Michael Jordan, Brown was not a great hitter. “It was his fourth sport,” Paul said respectfully on Friday when he heard his old opponent was gone. In order, Brown played football in the fall, basketball in the winter, was a high jumper in track and field, and somebody will have to explain to me how he managed to play baseball and lacrosse in the spring. There are tales of Brown playing in a baseball game, and when Manhasset was not in the field, he would leap a fence to and take a turn at the high jump, and then return and take his turn at bat. How did Brown come to Manhasset, at the base of Manhasset Bay, a few minutes from Port Washington? Born on Feb. 17, 1936, in coastal St. Simons, Ga., Brown came north with his mother, who cleaned houses in adjacent Great Neck. But Manhasset introduced the young man to civic leaders and coaches who promised him he would be comfortable in their school, and he wound up registered at Manhasset. He soon made himself felt – particularly on the football field. Paul Nuzzolese, 86, was a guard, bulked up over 200 pounds, who saw and felt Jim Brown up close. He recalls a fellow lineman -- “Big Joe, six-foot-three, built like Hercules, had a collision with Brown in the open field – never was the same.” My friend was talking on the phone from Florida; I could hear the shudder in his voice. (I have to proudly add: My pal Nuzzolese is now a member of the Wagner College athletic hall of fame.) As good as he was in football, Jim Brown was said to be the best lacrosse player who ever lived. It was impossible to dislodge the ball from the webbing at the end of his lacrosse stick, tight in his powerful hands. The legend is that Lefty James, the football coach at Cornell, wandered over to watch a Syracuse-Cornell lacrosse game one spring and blurted, “My God, they let him carry a stick?” (I think my late pal Dick Schaap, who played a bit of lacrosse, may have told me that story.) The money was in the National Football League, and Brown was the best, or very close to it. His path took him to the movies and some notoriety in his so-called private life and also a major role in Black activism of the ‘60s and well into this century. All of that is covered in the great coverage in Saturday’s New York Times and surely everywhere else. And then there were the homecomings. In 1984, Brown had mellowed enough to accept the induction into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, but obdurate as he was, he would only show up if the ceremony was held in his adopted hometown of Manhasset. He honored Ken Molloy, civic leader, and Ed Walsh, football coach, and others who treated him with respect, more than just a five-star athlete. I made the short drive to cover Brown’s induction. In the informal moments, I introduced Brown to my son, then 14 years old. “Nice to meet you, David,” Brown said, in that deep voice, shaking hands vigorously. I distinctly remember a crunching sound, although David does not quite remember it being quite that bad. Brown came home other times. One of his Manhasset teammates, Mike Pascucci, had done well in business, and had become a booster of one of the great institutions on Long Island, or anywhere – then named Abilities, Inc., now named the Viscardi Center, after the founder, Dr. Henry Viscardi – in nearby Albertson, L.I., where people are helped to work, to play, to live. (FYI: Edwin Martin, a frequent contributor to this site, was a long-time leader of the Viscardi Center and is a pioneer of services for the disabled; his wife Peggy has been an activist for easing young people into jobs.) Clearly, the Viscardi Center attracts good people. Once a year or so, Pascucci would invite his old teammate to visit the center. “They had a celebrity night,” Paul Nuzzolese recalled Friday, “They’d get athletes like Jack Nicklaus, Gale Sayers, Mike Schmidt, signing autographs. I saw Jim Brown get down on his knees and talk to those kids, and he would say how proud he was to be there.”  Jim Brown never lost his dedication to causes. I ran into him in the ‘90s, at some gathering in the city, I cannot remember the cause – health care and support for broken old football players, or racial causes. Whatever. Jim Brown was wearing a fez over his rugged skull, displaying a familiar hard look below the fez. Omigosh. I felt we were back in the late 60’s maybe in People’s Park in Berkeley, maybe outside Madison Square Garden or some other place that needed an attitude adjustment. The old days were back: Harry Edwards. Bill Russell. Roberto Clemente or Curt Flood giving writers a seminar in the clubhouse. Richie Havens. Nina Simone. Protest songs. The hallowed John Lewis. I saw a puzzled look on the face of a Black journalist, half my age, and I kind of giggled. Jim Brown’s scowl made me feel young again. And on the Manhasset-Port Washington peninsula, the earth still shudders from the powerful athlete who once played here. Isabel Wilkerson won a Pulitzer Prize when she worked for The New York Times. Later, she wrote a best-selling book about the great northward migration of Black Americans. In the process, Wilkerson earned a ton of airline miles, allowing her to fly first class much of the time. In addition to the few extra inches of space, Wilkerson was able to do research for her new book -- on the caste system in the United States. Even when she presented her boarding pass for Seat 3A, she was still treated as a stranger, a lower caste, as a female and as an African-American. Confused flight attendants stared at her and suggested she just keep walking to the back of the bus. Wilkerson also had to endure jostling for overhead-rack space from white male passengers. Anybody who is Black, or has friends and relatives of color, knows the drill. A few days after the 2016 election, Wilkerson settled into her first-class seat and noticed “two middle-aged white men with receding hairlines and reading glasses” who quickly bonded, with one stranger telling the other: “Last eight years! Worst thing that ever happened! I’m so glad it’s over!” The two instant buddies then celebrated from Atlanta to Chicago, assuming that the new President would be "good for businss." I am 100 percent positive that Trump's appeal to money guys helped advance the racism loose in the country. . Wilkerson’s book, “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” came out in mid-2020, before the little lovefest of assorted cut-throats and sociopaths and bigots and other Trumpites at the Capitol. I just caught up with “Caste” and found it compelling, as Wilkerson compares America’s enduring racial prejudice with the age-old caste system in India as well as the caste system that killed at least 6 million Jews and others regarded as untermenschen in Nazi Germany. Wilkerson points out how Hitler studied how whites in America marginalized and terrorized Blacks long after the so-called Civil War. Wilkerson also points out that contemporary Germany does not display statues and markers of the Hitler days, whereas the U.S. is only now coming to grips with Black youngsters having to attend schools named after Robert E. Lee, that old secessionist-slavemaster. It never went away. Wilkerson also presents dozens of examples of lynching and mutilation of Blacks, under slavery and long into the 20th Century, and still going strong in spirit. Trying to understand the American system in terms of the Indian caste system, Wilkerson flew overnight from the U.S. to London to attend an academic conference on caste, attended mostly by people of Indian ancestry, whether English or Indian or other nationalities. She immediately realized that the elite castes – even among academics -- were identifiable by lighter (Aryan) skin as well as a deep aura of entitlement, whereas members of the Dalit (Untouchable) caste – even with doctorates and other professional titles - - were of darker skin and reserved demeanor. She became friendly with a highly educated Dalit at the conference who described how his sister had cried about her dark skin when it was time to seek a husband. From her new friend, Wilkerson learned about Bhimrao Ambedkar, who renounced his Hindu standing and became a leader of the Dalits in the time of Gandhi. Her education about India will surely be the reader's education. As I read Wilkerson’s book, I thought about the new demographics in the U.S., as it heads toward a “minority” majority in the next decade or two. The white terrorists who stormed the Capitol in January are quite likely feeling marginalized by the talented and poised people of color who have become more evident in recent years. Some kind of change was gonna come -- or so some of us thought. It's been in the public consciousness for decades -- with the great Sidney Poitier embodying a possible new era in the 1967 movie ”In the Heat of the Night." For other examples, Wilkerson mentions the intelligent and handsome and poised couple that lived in the White House from 2009 to 2017, plus examples of changing America all over public life. As the pandemic endures, I gain information on the evening news from professionals like Dr. Kavita Patel of Washington, D.C., Dr. Vin Gupta of Seattle, Dr. Lipi Roy of New York and Dr. Nahid Bhadalia, with their kind and patient faces, with their knowledge and passion. The international look of today’s medical experts reminds me of that very good movie, “Gran Torino,” when Clint Eastwood, an auto worker with dark secrets from his military service in Korea, meets his new physician. (I'll never forgive Eastwood for his ugly televised rejection of Barack Obama, but his movie shows the growth of an aging bigot in a changing Detroit.) Last week, on MSNBC, Lawrence O’Donnell presented the viral immunologist who helped develop the Moderna vaccine -- -- Kizzmekia Shanta Corbett, Ph. D., who turns 36 on Jan. 26. Dr. Corbett saw the code for this new virus as it popped in from China, early in 2020, and linked it, in her mind, with anti-virus codes available here -- “over a weekend,” apparently. The rapport was clear between Dr. Corbett and O’Donnell, who is proud of being of Irish descent in Boston, and is one of the most open champions of African-Americans in public life. However, at the same time, a huge swath of white Americans is acting out in public, scorning vaccinations and masks, storming the Capitol a year ago, yelling racial insults at police while trying to brain them with heavy weapons. Many white Americans grew up thinking they had an edge over anybody with darker skin. Isabel Wilkerson’s powerful book points out the growing strains on the old American caste system. * * * Dwight Garner, one of my favorite writers at the NYT, reviewed “Caste" in July of 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/31/books/review-caste-isabel-wilkerson-origins-of-our-discontents.html Lawrence O'Donnell's interview with Dr. Corbett -- real life, not a movie:  Rep. Elijah E. Cummings, 1951-2019 Rep. Elijah E. Cummings, 1951-2019 I started calling him “The Prophet” in 2008 during a tense Congressional hearing about the drug epidemic in Major League Baseball. With Biblical emphasis, Rep. Elijah E. Cummings scolded the stewards of baseball for tolerating the widespread usage of performance-enhancing drugs during the home-run frolics in the recent generation. His powerful figure and righteous stance was befitting the prophet who is honored by Jews, Christians and Muslims. “This scandal happened under your watch,” Representative Elijah E. Cummings, Democrat of Maryland, said in “Field of Dreams” gravity to Commissioner Bud Selig and Donald Fehr of the players union during the Congressional hearing last Tuesday. “I want that to sink in. It did.” That’s what I wrote back then, and I followed him from afar as he dominated Congressional hearings during the disgraceful time of Donald J. Trump, trying to motivate see-no-evil Republican representatives with a Biblical exhortation: “We’re better than this.” Amen. I was horrified to see how weary he appeared during those hearings early in 2019, and I was not surprised when he passed months later. He gave it all he had. Now Elijah Cummings is returning to Congress, in the form of a portrait by a young Black artist from Baltimore, Jerrell Gibbs. The story of the artist and the work is in the Sunday New York Times and, I am sure, elsewhere. But are “we” better than this? And who is “we?” I ask this as Elijah Cummings’ nation seems to be degrading itself, day by day. Just a few examples: --- A thick swath of adults are refusing to take Covid vaccinations that would protect themselves and their loved ones and other human beings – virus droplets as lethal as, well, bullets. -- Politicians in many states are conniving to make it more difficult for American citizens to vote. -- And people are scooping up all forms of rapid-fire guns to prepare for, well, for what? “I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children” – “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” Bob Dylan, 1963. (Talk about prophecy.) Let us swerve to 2021 – in the wake of the Rittenhouse decision in Wisconsin -- when parents in Michigan bought a very lethal pistol for their 15-year-old son. The boy (“in the hands of young children”) gives off appeals for help, and is ignored by his parents. His obsession with the weapon is noticed by school officials who, at the very least, notify the mother, whose reaction is to send her son a snarky (sign-of-the-times) text message: “LOL I’m not mad at you,” Jennifer Crumbley texted her son. “You have to learn not to get caught.” The next day, her son killed four classmates and wounded many others in the high school. Then she and her husband went on the lam and were flushed out in downtown Detroit. Now it appears that Mrs. Crumbley wrote a letter to none other than President-elect Trump in 2016, praising his stance on freedom to carry a gun.  “As a female and a Realtor, thank you for allowing my right to bear arms,” she wrote, according to The Daily Beast. “Allowing me to be protected if I show a home to someone with bad intentions. Thank you for respecting that Amendment.” She complained about parents at other schools where the “kids come from illegal immigrant parents” and “don’t care about learning.” In her own way, Jennifer Crumbley was prophetic. When I read her screed, I began to think of others - young guns, so to speak -- who scorn the country they allegedly serve. The sneer on the young man’s face reminds me of members of Congress named Gaetz, Hawley, Cawthorn, and the unleashed aggression in the mother’s “LOL” text reminds me of sneering warrior-representatives Greene and Boebert. Are “we” better than this? Soon the august presence of Rep. Elijah Cummings will take its place in the Halls of Congress. I hope his ideals will grace those who walk past.  Dr. Charles Stacey, black shirt, gives a tour to two Chinese students and their college prof. Dr. Charles Stacey, black shirt, gives a tour to two Chinese students and their college prof. There’s a new TV series with Jeff Daniels playing a sheriff with tangled loyalties, in a faded steel town in the Mon Valley of Pennsylvania. As soon as I heard about it, I said, “Hey, wait, I know that place.” I came to know it, and root for it, in 2009-10, when I was working on the biography of Stan Musial, the great star of the St. Louis Cardinals, who grew up where the Monongahela River twists between the hills and fading towns and dormant steel mills. Humankind has since screwed up a lot more places, probably irrevocably. The Mon Valley was a signpost, a warning, of what we were doing. After the steel mills and coal mines were played out, some people were still living in, essentially, the ruins. That is the site of the new series, “American Rust,” from the book of the same name, by Philipp Meyer, which had just come out in 2009, when I began my research on Musial and his roots. Musial’s dad had migrated from Poland to work in the mills, joined by immigrants from Europe and Africa and the east coast. I read that the new series was filmed in studios in modern high-tech Pittsburgh, but some of the exteriors were shot in Monessen, just across the Stan Musial Bridge from Donora, where Musial grew up. He played basketball and baseball for Donora High, but his first baseball tryout was conducted in Monessen, where the St. Louis Cardinals had one of their many farm teams. From what I read, Daniels’ TV town is as gray as the smoke-filled skies from the 1948 Halloween killer smoke cloud, known as “The Donora Smog.” (Stan Musial’s dad, Lukasz, breathed too much of that smog, trapped under an inversion on that October night, and was dead two months later – too much American rust in his lungs.) Musial was no longer capable of giving interviews when I worked on the book – he would die in 2013 -- but other people took me around the valley. One of my tour guides was a local hero named Bimbo Cecconi, a former Pitt football star and coach, now living up near Pittsburgh, who walked the hills of Donora and told me about the athletes from his hometown – Deacon Dan Towler of the Los Angeles Rams and Arnold Galiffa who played at West Point, and three generations of ball-playing Griffeys – Buddy and Ken and Ken Junior. Bimbo escorted me to the Donora Public Library where Donnis Headley became a helpful source. When the Donora microfilm machine was out of commission, she directed me across the river to the Monessen library, where I read old clips about Musial and the two towns. My other guide was Dr. Charles Stacey, who had been the superintendent of schools, and still lives on the main street, McKean Ave. Dr. Stacey gave me a black T-shirt with the legend Donora Smog Museum, which he had opened in the shell of a former Chinese restaurant. Dr. Stacey was also a mentor to Reggie B. Walton, once a football star on the verge of gang trouble, who willed himself to a historically Black college and a federal judgeship in Washington, D.C. Judge Walton is a Republican who has delivered decisive and apolitical rulings. As I walked around with Dr. Stacey, I expressed interest in talking to Judge Walton A week later, my home phone rang and a man said, “This is Reggie Walton….” He said Charles Stacey had asked him to call me – one of the honors of my working life. I wonder if this new series will take note of this accomplished judge who came out of the American Rust. I learned other things from my days in the Mon Valley. -- “Monongahela” is of Native American origin, meaning “river with the sliding banks” or “high banks that break off and fall down.” --A young surveyor from Virginia, George Washington, was an aide to Gen. Edwin Braddock who was killed in action further downstream in the French and Indian War in 1755. -- The names of Monessen and Donora are both amalgamations. --- Monessen’s name is a salute to the German emigrées, from the industrial town of Essen. -- Donora was named by industrialist Andrew Mellon of Pittsburgh, who built a new steel town at the end of a freight line. Mellon honored W.H, Donner, an executive who had made a lot of money for him, and also honored Mellon’s young wife, whom he had brought over from Europe -- Nora McMullen. The Mellon marriage did not last long but the odd mixture of names survives in a gritty town with memories. I came away from my visits to Donora and Monessen with the same rooting interest I have for Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, further down the Appalachian chain, where I used to work. I cringe when I hear about the rampant use of opioids, the crime statistics, the dropouts, in Appalachia, and I gather that is the backdrop to this new series. I’ve seen a few of Jeff Daniels’ interviews on TV, and he always stresses that while he works in Hollywood or Broadway, he always goes home, to Michigan – “Fly-Over Country,” I heard him say, using the ironic term midwestern people use for their part of the country. Maybe I’ll catch some of “American Rust” sometime; (I don’t have Showtime on my cable package.) Some of the reviews I’ve read are not ecstatic, but I wonder: is Appalachia just not sexy enough for Americans? After all, “The Sopranos,” in tense urban New Jersey, was the best TV series I have ever seen, and “The Wire” made people pay attention to inner-city Baltimore. I just hope the writers – and the viewers -- do right by the Mon Valley. ###  Clint Smith at Monticello Clint Smith at Monticello I just read a great new book: “How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America,” by Clint Smith. Smith’s main point is that people, northerners and southerners, are now learning things about slavery they were not told in school -- the depths of depravity by which a female slave could be labelled a “good breeder” by her owners, and other aspects of good old-fashioned American enterprise. Many people in this country still see slavery through a sentimental haze: slaves were better off here than they would have been in Africa; they were handled benevolently at the plantations. You know, good people on all sides. Nowadays mayors and school boards and governors are trying to forbid controversial or academic critiques of America. (Some of these moronic governors are aiding Covid by not mandating vaccinations and masks at work and school.) Smith’s book about slavery lies is a companion to the so-called “Big Lie” about alleged election fraud and the merry tourists who flocked to the Capitol last Jan. 6. For all the chicanery and cowardice in high places, the worst parts of slavery are impossible to hide as Smith makes his rounds. As a one-time news reporter, I respect his shoe-leather approach -- visiting hot spots of the slave trade. A staff writer for the Atlantic – and a poet – Smith interviewed tour guides and museum directors as well as tourists, plus participants in Confederate commemorations. The new cadre of historians and guides make it clear that that people, white people, mostly male, not only performed violent deeds but also knew what was being done, mostly in rural and southern states. Smith begins where, in a sense, the country began – Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, where he "owned" slaves while preparing to write the Declaration of Independence. While he put pen to paper, his white staff put whips to the backs of Black slaves. Background music for Jefferson. At Monticello, Smith chats with two visitors -- white, Fox-watching, Republican-leaning women, who hear a guide talk about Jefferson’s long association with a female slave. Speaking to Smith, who is Black, the two women seem aghast. Smith quotes one of them: “’Here he uses all of these people and then he marries a lady and then they have children,’ she said, letting out a heavy sigh. (A reference to Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, who bore at least six of Jefferson’s children. The two were never married.) ‘Jefferson is not the man I thought he was.’” That is the theme of the book – many Americans in position of responsibility and knowledge deliberately deflected what was known about slavery. And not just in the South. I know somebody who did college research on commerce in New England, and never came across the mention of slaves in Yankee states. Then again, in a 2020 farewell to the great John Thompson, I praised a recent book about Frederick Douglass and noted that in all my school years in New York (with many history electives in college), I never heard the name "Frederick Douglass." (To be clear, I did know his name, just not from school. Our parents were part of a Black/white discussion group, and they extolled heroes like Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, and all of the children have learned from our parents.) Smith points out that the Dutch and English, who pushed out the Lenape natives, welcomed slaves on the oyster-laden shores of lower Manhattan, and used them for labor, and shipped thousands to farms and other towns. New York was the second largest entry port, distributing slaves culled from Africa. Those who died were tossed, unmarked, into a pit near Wall Street. One chapter in this book about slavery jarred me because I did not see it coming – a visit to the dreaded Angola Prison in Louisiana. Smith explains his visit to Angola by pointing out that Black prisoners worked for free or for pennies, at the penal equivalent of plantations. In fact, Angola had a big house, where the warden and his family were served by trusted Black prisoners. Prisons as plantations: As it happens, I have heard the metallic clank of the heavy door slammed behind me in three different prisons – and all three stories involved Black men. (See the links below.) Smith’s itinerary includes: Monticello Plantation, Va.; the Whitney Plantation, La.; Angola Prison, La.. Blandford Cemetery, Va., Galveston Island, Tex, where emancipation was belatedly revealed to Blacks, leading to the recent proclamation of a new national holiday -- Juneteenth; New York City; and Gorée Island, Senegal, the legendary focus for the African slave trade. In a moving Epilogue, Smith interviews his own elders for stories of prejudice, slavery and downright brutality they experienced or heard from their own elders. Clint Smith’s book makes it clear that white America knew more about slavery than it discussed -- just as many of our "public servants" like to talk about sight-seers who had a fun day in the Capitol last Jan. 6, brandishing flagpoles, gouging eyeballs and shouting racial epithets. It never went away. It’s who we are. * * * Two book reviews in the NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/books/review/how-the-word-is-passed-clint-smith.html Three of my stories from prisons, when I was a news reporter: https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/09/archives/frazier-sharp-in-tough-prison-talk-show-frazier-sharp-as-he.html https://www.nytimes.com/1972/10/02/archives/new-jersey-pages-a-scholar-in-the-new-alcatraz-felon-finds-himself.html https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/12/archives/carter-reacts-stoically-to-denial-of-new-trial-i-hope-im-still.html * After writing this piece, and reading the thoughtful comments, I discovered a new book: “Land,” by Simon Winchester, a writer with great and varied interests. (We met in 1973 when he was posted to Washington by The Guardian.) Now living in the U.S., Winchester is writing about the creation and development of land.

An early paragraph about the original inhabitants of this continent fits right in with the tone of this discussion: (Page 17) “The serenity of the Mohicans suffered, terminally. The villagers first began to fall fatally ill – victims of smallpox, measles, influenza, all outsider-borne ailments to which they had no natural immunity. And those who survived began to be ordered to abandon their lands and their possessions, and leave. To leave countryside that they had occupied and farmed for thousands of years – and ordered to do so by white-skinned visitors who had no knowledge of the land and its needs, and who regarded it only for its potential for reward. The area was ideal for colonization, said the European arrivistes: the natives, now seen more as wildlife than as brothers, more kine than kin, could go elsewhere.” Winchester’s newest book then goes in many directions. I look forward to reading the rest. However she did it, Naomi Osaka found a way to catch the attention of all the people around her.

She dropped out of the French Open Monday, saying she has been suffering from depression since 2018. Whatever the circumstances, however she did it, she now gets better help, I hope. Osaka rang the alarm by saying she didn't want to talk to the media, but now it is clear this is much more than a tantrum by a young adult. My one question now is: who knew about her trouble? Who let it get this far? Did she have a worldwide number for a qualified counselor who knew her, who was reachable 24 hours a day? One more thing: Tennis -- with a capital T -- is also to blame. I once knew a doctor who was appalled at the lack of consistent care these great athletes receive. Nothing was available for the next doc-on-call in the next continent to make a diagnosis. Maybe it's better now. But there Naomi Osaka was, in yet another great setting, in yet another Slam tournament, needing to shut it down. Everybody's meal ticket. Did her parents know? Her coach? Her agent? Her hitting partner? Her physio? I am way out of tennis these days and know nothing of her and her "entourage." But she had to draw the line somewhere, and the media is a fine target, I don't blame her. The tennis writers and commentators I know would be the first to say: brave lady, get some help, then come back. If you can. If you want. Be safe. * * * Here is Matthew Futterman's breaking news story from Paris: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/sports/tennis/naomi-osaka-quits-the-french-open-after-news-conference-dispute.html?searchResultPosition=2 * * * (The following is my earlier piece.) How much is it worth to not speak to the scurrilous wretches known as tennis writers? It is refreshing to know that professional tennis pays so well that Naomi Osaka can willingly pay $15,000 to avoid one short session with the assassins and cut-throats of the press. This was the going rate when Osaka ducked the media after her first round at the French Open on Sunday. She had promised not to speak, citing the threat to “mental health” from exposure to the troublemakers with pens and recording machines. Up to now, Osaka has been known for becoming the best female player in the world and also becoming the highest paid female athlete in history, making $34.7-million dollars last year, according to Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kurtbadenhausen/2020/05/22/naomi-osaka-is-the-highest-paid-female-athlete-ever-topping-serena-williams/?sh=3a174251fd33 As the daughter of a Haitian father and Japanese mother, representing Japan and growing up in the United States, she has worldwide appeal, and has often spoken out maturely on gender and racial issues. But suddenly, at 23, apparently on her own, she issued a manifesto that she would not appear at the mandatory conferences after every match. Having covered these post-match conferences since I was younger than Osaka is now, I can attest to the rambling and scattershot tone of these sessions. Most of the accredited media members are from the tennis press – they know the sport, they are solicitous of the players, asking questions about on-court strategy, questionable officiating, luck of the bounce, and upcoming tournament plans. (“Will you be playing at Indian Wells this season?”) Of course, there are also outliers – columnists, news reporters, and nowadays people representing websites and electronic media, looking for a snippet of quote or tantrum or tears. Over the years, I have seen most of the enduring players adjust to sudden swerves of questions just as they adjust to swirling winds or glaring sunlight or capricious surfaces. Nobody gets to major tournaments without learning to cope. Serena Williams deflects questions and criticisms with a combative mode. Her older sister Venus Williams does it with a distant manner; she doesn’t really know anything about this or that. But when they want, both are mature activists for themselves and good causes. Many of the enfants terribles had their own defense mechanisms – John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors ramped up their obnoxious level, Andre Agassi retreated into a “whut?” response, Ivan Lendl could get haughty. Guys being guys. It got them through. The best female players were even younger when they came along, facing questions that often veered into personal issues. Some of the female prodigies seemed preternaturally poised – Chris Evert, of course, as well as Pam Shriver and Steffi Graf and Tracy Austin and Martina Hingis and Ana Kournikova most of the time, even when some male reporters seemed to be summoning their inner Humbert Humberts in person and in print. Female players had marvelous role models – the pioneers who fought for respect and prize money, most notably Billie Jean King. Some women had to face sniggering sexuality questions, most notably from the Beastie Boys of the British press, at post-match press conferences. I remember one female player being asked whether she was wearing an engagement ring from the woman in the family box. The volunteer steward at the Wimbledon interview room in the '80s was a mannered scion of a major British firm, who would wave off some personal questions – “please, tennis questions only.” I have seen John McEnroe and Martina Navratilova tell him politely they were more than equal to the questions. Which they surely were. Up to now, Naomi Osaka has been able to handle herself – on the court and in the media conferences. Her manifesto seems to have come from within, without advice from family or agent or coach or friends. Nobody seems to know the origin of her phrase “mental health,” but surely Osaka has seen players be mad or hurt by questions after a loss or a dispute. Perhaps she has been, also. I can only hope she is talking with people who care for her, including veterans of the tour – Evert and Navratilova. I would suggests she check in with a Black pioneer like Leslie Allen of New York City, who was on the tour back in the day when prize and endorsement money was measured in tens and hundreds. Unless there is more to Osaka’s angst than we know, she needs to remember that if she can face down the great players on today’s tour, she can handle the Beastie Boys (and Girls) in the media room. We’re the easy part. What a waste. Nearly four years, over 235,000 lives, untold damage to the environment, friends betrayed, alliances broken. What a waste. But now we have a chance to start over, and I want to credit one source for the grace and vision and strength behind this chance to recover -- the Black public figures who made such a big difference. In the same year that a white police officer openly ground a Black man’s life into the pavement, the best and brightest helped elect a centrist who might, just might, pull some disparate parts together again. The tone of this election year was set by Blacks who have been preparing for years, for decades, for centuries, for this moment. One great part was former President Obama sinking a feathery impromptu shot as he strolled through a gym – one and done – and as he kept moving he said, over his shoulder, “That’s what I do” -- Just as when he sang “Amazing Grace” in a church honoring slain members. The tone of this election year was set early by Sen. Kamala Harris who began a primary debate by reciting racial injustices to one of her competitors, former Vice President Joe Biden. He blinked and took it, seemed to be listening, and months later he had the grace to select this accomplished lawyer/prosecutor/campaigner as his running partner. Grace under pressure, by both. * * * Now I want to praise four others who raised the grace level in this country: Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland passed last year, after setting a high level of righteousness in Congress. I witnessed him leading some sports/drugs hearings years ago, and ever since I have referred to him as The Prophet. In his final months, he admonished balky witnesses, “We’re better than this.”

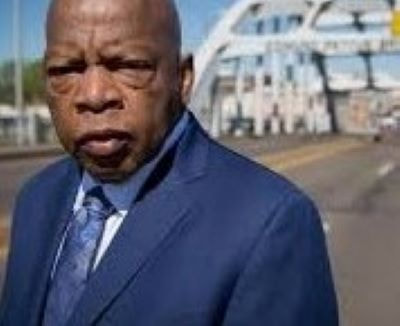

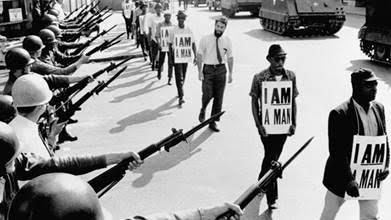

Rep. John Lewis also did not make it to this election, but he had been setting an example since the police beat on him back in the ‘60s, at lunch counters and on the Pettus Bridge. He survived that, served in Congress, seeming so innocent but actually a living holy man, tempered in the flame. Stacey Abrams lost a narrow race for governor in 2018, and soon used her intelligent smile, her knowledge, her persuasiveness, to help register voters – Black voters – in the South, where the desire to vote means standing on line in heat or rain for many hours, by Republican plan. This week, Abrams’ work helped throw two Senate races in Georgia into runoffs, early in January. Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina changed history by endorsing Joe Biden, who had just gone through two disastrous primaries in the frozen North. Clyburn is one of the most composed of politicians, no bluster, no swagger, just serene confidence. He read the mood of South Carolina perfectly, and gave the nation a Democratic candidate who could balance the disturbed posturing and fatal incompetence of Donald Trump. * * * The positive effect on this nation will carry over into the new year, the new regime. Trumpites gloried in their man depicting Philadelphia, any urban setting, as dangerous, but a white President and a Vice President who is part Jamaican and part Indian live up to the professed ideals of this country. As it happens, my family has some Jamaican and some Indian ancestry, as well as Black American, and Latino, and Asian, all kinds of Europeans, including the lady I live with who can trace herself to William the Conqueror and early New England settlers. One young man in the family – with some Black ancestry -- called his grandmother in a nearby Atlanta suburb on Saturday to deliver the news that Biden had won. * * * And Saturday evening, a joyous, liberated, masked, socially-distanced, horn-honking, all-colors-of-the rainbow-crowd in a parking lot in Delaware greeted the new look of the Biden and Harris camps -- people who seemed to like each other, and love their children and speak comfortably of making this country work for everybody. The mixed racial makeup in that crowd seemed to match the impromptu crowd in the streets of Minneapolis when George Floyd was murdered, only this time not to protest but to cheer, to smile, to breathe, Maybe, just maybe, things get better. The above quotation came from Ronny Thompson, a Georgetown basketball player back in the day, describing the leadership style of his coach, that is to say, his father.

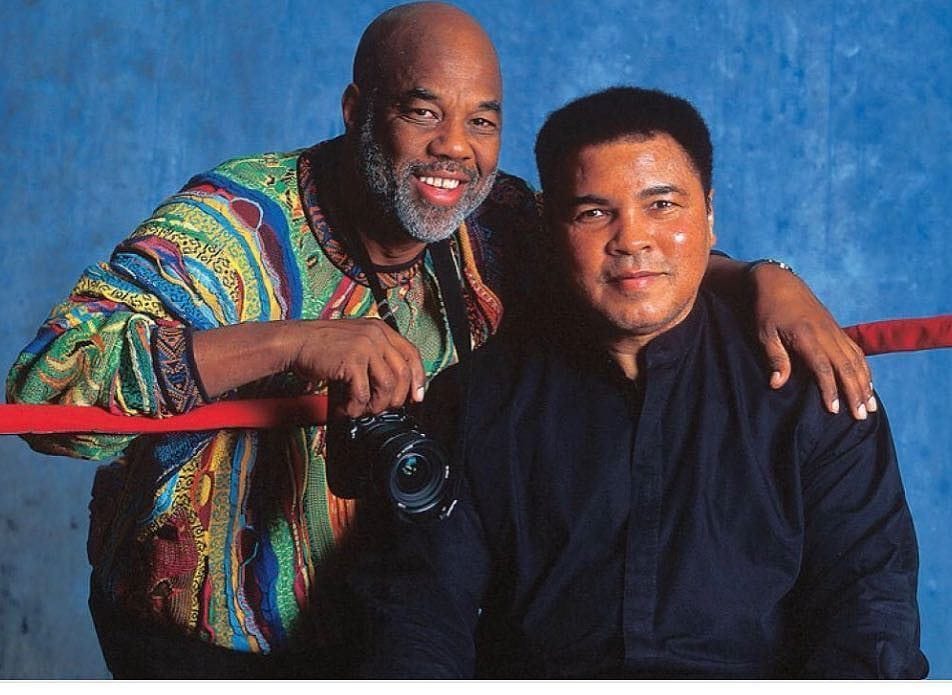

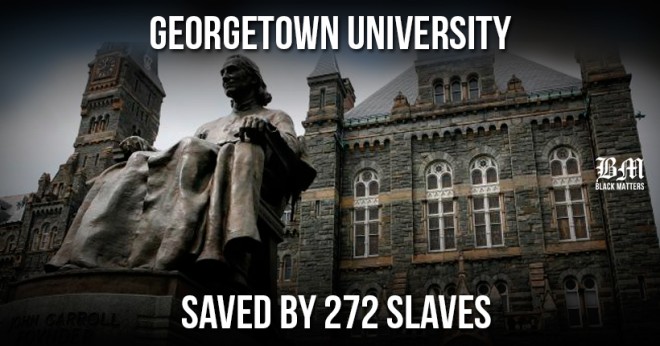

John Thompson, Jr., the long-time basketball coach at Georgetown University, died Sunday night at 78. He did things his way, defying any definition imposed by others. If you praised some aspect of his leadership or coaching, he bristled, blustered, maybe even dropped an epithet. I got a first-hand view of his bombast in 1984, days before Georgetown won the national Division I basketball championship. I had called the president of Georgetown, Father Tim Healy, to assess the impact of Thompson on his players, almost all of whom were Black. ''This is a man from the Washington area who is taking kids who don't have two coins to rub together and is literally teaching some of them how to use a knife and fork,” Father Healy said in my column before the Final Four. “He knows just what he's doing, “ Father Healy continued. “And we at Georgetown support him in what he's doing.'' At the press conference before the Final Four in Seattle, Big John went off, loud and clear. I distinctly remember him denying that he ever taught anybody to eat properly and I distinctly remember him saying: “I ain’t no Jesus Christ.” He did not mention Fr. Healy or The New York Times (or me) but it was clear he had read the column and was not amused. John Thompson surely had a powerful role in the lives of many of his players. Of the players who stayed with the program, the graduation rate was said to be 97 percent. Some left early, to be sure, but while they were there, they all had to play relentlessly, without any frills to their game. Thompson once said a certain player would be all right as soon as he dropped “the old Boogaloo” from his game – meaning, fancy moves, fancy passes. He expected people to know what he meant by “the old Boogaloo.” No definitions. In Thompson’s time, Georgetown had an academic advisor, Mary Fenlon, a former nun, on the bench. Fenlon, who passed in late 2019, was said to be witty and sociable, but in public she was as inscrutable as Thompson. His model player was Ronnie Highsmith, an Army vet who was four years older than the stars and would lend physicality on the court and discipline off the court. The players succeeded, under Thompson's model of discipline and education. As it happens, I am currently catching up with the biography, “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom,” by David W. Blight, published in 2018. (I believe that I went through grade school through college without ever hearing a mention of Douglass.) The book tells how Douglass, the escaped slave, educated himself to become a writer and speechmaker and caustic critic of Abraham Lincoln when he saw fit. His larger-than-life persona pushed America toward the Emancipation Proclamation. America has gained from black critics and activists. Early in my career, I ran into powerful figures like Harry Edwards, the academic, and Jim Brown, the football player, and Bill Russell, the basketball winner (for whom Thompson was an understudy for two years.) Nowadays, athletes like LeBron James and Maya Moore and Renee Montgomery are setting a tone, just as John Thompson did once as a protest. My friend and colleague, Harvey Araton, AKA The Rebbe of Roundball, has a knowing column on Thompson, the activist, in the Tuesday NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/31/sports/ncaabasketball/john-thompson-georgetown-ewing.html?searchResultPosition=2 Like Frederick Douglass, John Thompson did not talk about his feelings, his inner reactions. He had a posture and he stuck to it. Ronny Thompson’s evaluation of his father was perfect. * * * My column quoting Father Healy: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/03/26/sports/john-thompson-s-wall.html?searchResultPosition=1 https://www.nytimes.com/1993/02/19/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-coaches-get-some-sympathy.html https://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/11/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-rookie-has-earned-his-minutes.html?searchResultPosition=1 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/31/sports/ncaabasketball/john-thompson-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1 “I suspect that seeing NYC burn arouses strong feelings in you,” writes a friend from Queens, long living overseas.

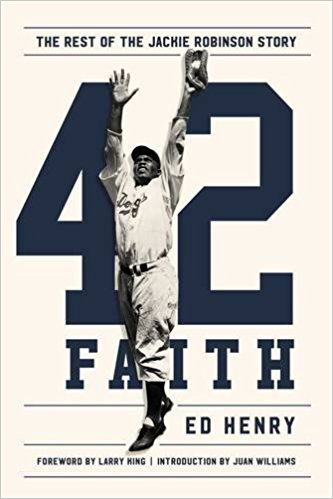

* * * We sat in our den with a visitor from Moscow and watched smoke pour out of the Parliament building. This was October of 1993; our friend was frightened because her son was a journalism student in Moscow and she knew he would get up close, to observe, to report, maybe to protest. Now it is our turn. My wife and I sit in the same den and watch our country – places we have lived and visited – quiver with rage. One over-reaction and we could have Moscow-on-the-Hudson, Tienanmen-Square revisited. I feel the way our friend must have felt that warm autumn day when she watched smoke rise above the Moskva River. New York is my hometown and it’s in my blood, ever since my father took me around, teaching me names and histories. I still see New York through the prism of being 5 years old and watching Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an old white wizened president, campaign through Queens in an open limo during a cold drizzle, or being 7 and having my father call from the office and say our team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, had just signed Jackie Robinson. I see New York from memories of gentle folk, bootstrappers from Queens, who met sometimes in my family living room, in a discussion group strictly maintained at a 50-50 black-white ratio. So many white people have lived more comfortable lives because of the enslavement of so many black people. We can’t get past it. It would be interesting if we could go back in time with those nice people, long gone, and in 2020 terms discuss America’s Original Sin. Now, from my safe perch in a nearby suburb, I feel viscerally sick when I see video or photos of broken windows, burning cars, confrontations. People are expressing their horror at the murder, caught on a smartphone camera, of George Floyd by four police officers in Minneapolis. I feel proud of the Americans who have flocked, mostly in peace, to express their believe that Black Lives Matter. The Floyd family has cited religion to score violence and revenge, but this is not a cool time, and I know there are bad actors, white and black, who want to cause anarchy and fear. The rock-throwers and the window-breakers will give racists a chance to break heads in the name of law and order. (Tom Cotton, you old op-ed sage, I’m talking about you.) I’ve been lucky to travel all over the States -- Minneapolis-St. Paul, Atlanta, Seattle, LA, Chicago. For two years in the early 70s, we lived, on assignment for the Times, in Louisville, Ky., -- five homesick New Yorkers nevertheless blessed with two stimulating years. The other day, from Louisville, I saw a story that gave me hope, or rather temporary hope – a human chain of white women at the front of a protest, ahead of black protestors, sending a physical and emotional message: “We got you.” Our next-door neighbor in Louisville would be so proud of these protestors. Rabbi Martin Perley had built bonds with the African-Americans of the 60s, so that when Louisville seemed ready to go up during a protest, he joined other civic leaders in walking the city’s West End, urging people not to take out their rage on their town. So I was proud of the white women of Louisville who went up front, but then I read about the police shooting of a well-known BBQ merchant on the West End, who may have fired a pistol in response to looting outside his door. So we’re back where we started with George Floyd. Now it is our turn in the TV den to watch nightly confrontations in New York. I spy a street or building or bridge and know exactly where it is. I have walked there and chatted with fellow New Yorkers; I have ridden the buses and subways; I drive comfortably all over my hometown. In my home borough of Queens, the Cuomos lived 10 blocks to the east of my family and the Trumps lived 10 blocks to the west of our busy, noisy street. Most days, Cuomo is hectoring New Yorkers to stay smart about social distancing and keeping an eye on the bumblings of the mayor. On Friday that disturbed and dangerous president brayed that George Floyd would be so proud of the big stock-market leap. What a jackass. Trump is the Republicans’ kind of guy. We are all paying for the anarchy and hate and stupidity he has emitted. Still, I take hope when I see blacks and whites, Latinos and Asians, mostly young, demonstrating their idealism, while we sit in front of the tube, like our friend from Moscow once did. On Thursday, a federal judge characterized the public statements of Attorney General William P. Barr as “distorted” and “misleading” in his early descriptions of Robert S. Mueller III's report last year. I missed the name of the judge at first, but later the name drifted from the television in the next room. “Oh, my God, that’s Reggie Walton!” I blurted, a bit informal toward a prominent judge. I learned about Federal Justice Reggie B. Walton a decade ago when I was writing a biography of Stan Musial, the great baseball player from Donora, Pa. I was blessed to have two mentor-guides to that hard-times steel town: Bimbo Cecconi, one of Pitt's great athletes, and Dr. Charles Stacey, the former school superintendent and a town historian who was proud of both Musial and Walton. “You ought to talk to Reggie Walton,” Dr. Stacey said. Later, on his own, he called his star pupil and suggested he give me a ring. That is the Donora connection – the pride of people who survived the mills and the streets and the hard times. There was a history to Judge Walton. His parents worked hard -- the job market was always tougher for African-Americans -- and had high hopes for their son. Reggie was a competitor, who goaded his football teammates not to quit against much bigger teams, but he also ran with a tough crowd. In his senior year of high school, he thought he was going to a fist fight between two gangs from opposite sides of the Monongahela River. Somebody pulled a sharp object and a boy from the other side was stabbed. Reggie Walton helped him get medical help, and then he decided to make himself scarce from gang activity. People in town pointed him toward West Virginia State University, a historically black college, to play football, and maybe to study. The football was all right, but the studying was better. Reggie Walton is now a federal district judge in Washington, D.C., who has been in the news a few times since being appointed by President George W. Bush. In 2005 the judge broke up a street brawl near the courthouse, and in 2007 he presided over the trial of I. Lewis (Scooter) Libby, for outing a C.I.A. agent. The jury convicted Libby and the judge sentenced him to 30 months, but President Bush set him free, and President Trump later pardoned Libby. The judge was reportedly not amused, either time. I finally got to meet Judge Walton in 2011 as he prepared for the perjury trial of Roger Clemens in the steroids frolics. Maybe because of his former school superintendent, Judge Walton agreed to meet me, on the grounds that we not discuss Clemens, at all. I thought maybe I could slip in a question or two, but after five minutes in his office, I knew better than to try to make a fancy journalistic feint through Judge Walton's defense. Nobody pulls the okey-doke on Judge Walton. I was in the courtroom in the first hour of the Clemens trial, when the prosecution alluded to a witness who had been ruled off limits. The highly-paid defense lawyer stuck up his hand and made an objection and the judge called a timeout, saying he needed a few minutes to think it over. After consulting his colleagues in back chambers, the judge declared a mistrial. This year Judge Walton was assigned a case questioning whether the attorney general had accurately portrayed the Mueller report long before the public could see it. The judge alluded to “inconsistencies” from the attorney general. In football terms, the liaison between the president and the attorney general has produced a dirty game for the past three years -- lots of grappling in the mud, kneeing and gouging in the pile. All I know is, when the oblong football skitters loose in a legal scrimmage, I want it to roll near Reggie Walton, from Donora, Pa. The article I wrote in 2011 before the brief Clemens trial:

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/03/sports/03vecsey.html Judge Walton's official website: https://www.dcd.uscourts.gov/content/senior-judge-reggie-b-walton We sat in front of the tube Sunday night and made that exclamation, watching a politician kiss his husband and then deliver a gracious and hopeful speech.

The love in the room was tangible, following months of campaigning by Mayor Pete in far corners of the United States, where he was treated with respect and affection by wide swaths of the population. In the narrow sense, this was not a triumph, since Buttigieg had just been ignored/rejected by voters in South Carolina, who had other agendas, quite understandable. But Buttigieg knew he had taken his youth and hope and skill to the American public and received votes, delegates, and promise of a future. So, yes, this scene was not something we had thought we would see in a national election, any time soon. In a way, it reminded me of the hope of turning, dare I admit it, 21 in the election year of 1960, and seeing a candidate I thought represented youth and idealism, John F. Kennedy, beating Richard M. Nixon. For anybody believing in equal opportunity, there was pride in that religious barricade coming down, but much more it was the hope of another generation coming along, that would sort things out, or so we hoped. More to the point, Buttigieg’s speech, clearly without prompters or notes, celebrating values like honesty and equality and facts, reminded us of a speech at the Democratic convention in 2004, by a senator, of color. My wife caught it live, and told me about it, and said Barack Obama would be president, and soon, because he could express the hope and ideals of the nation. Four years later, we saw an appealing family, husband and wife and two little girls, walk onto a stage in Grant Park, Chicago, to acknowledge being elected president. “Did you ever think you’d see that?” I can only speak for myself, but the magical sight reflected to my upbringing, the highly “progressive” political values of my family – the adoration for Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband, the records by Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson in our house, and the discussion group of working class people in Queens, intentionally maintained at 50-50, black and white, that sometimes met in my family’s living room. How often do you see family ideals expressed on worldwide television from a jammed lakeside park in Chicago? For all the birther crap being spread about the Obamas, this was a family victory. Now it is a gay couple, Pete and Chasten, married, kissing in front of the world, celebrating the reality that Mayor Pete had been accepted – chosen in primaries and caucuses – particularly by older folks, in a time when younger people are much more comfortable with gender diversity. And then Mayor Pete gave a speech that reminded us of Barack Obama in 2004. Nobody knows what will play out in the coming days and months. I won’t even go into the glaring and dangerous failures of the current president. I only know that Mayor Pete kissed his husband, and gave a great speech, and that made us feel better, if only for the moment. “Did you ever think you’d see that?” It's Black History Month in the U.S. -- time to acknowledge people who have succeeded despite the shackles of slavery and segregation -- America's original sin, still hanging over us.

By sad coincidence, two of America's great strivers passed within days of each other, and have been honored in lavish and literate obituaries by two star writers in The New York Times. Katherine Johnson and B. Smith both had singular success in demanding fields, breaking barriers and stereotypes. Mrs. Johnson escaped segregated schools to qualify as a mathematician for NASA, and later made the pre-computer calculations that helped take American astronauts into space. (My Appalachian buddy, Randolph Fiery, points out in a Comment below just how difficult it was for Mrs. Johnson's parents to seek a high level of education for their precocious daughter, involving a long trek over the mountains of West Virginia.) Katherine Johnson and her black female colleagues were later depicted in the movie “Hidden Figures.” She died at 101 on Monday in Virginia and was honored in an obituary by Margalit Fox. “NASA was a very professional organization,” the obituary quoted Mrs. Johnson telling The Observer of Fayetteville, N.C., in 2010. “They didn’t have time to be concerned about what color I was.” B. Smith began as a model, wrote and was a television host and designed household goods, but was best known for the restaurant bearing her name in the Theater District of Manhattan. She died at 70 on Saturday on Long Island. The obituary by William Grimes told how Barbara Smith from Pennsylvania was a dynamo in childhood: “I inherited a paper route, I sold magazines, had lemonade stands, I was a candy striper and into fund-raising,” she told The Times in 2011. “I’ve always enjoyed being busy.” She had her self-image, and she was not shy about describing it: “B. Smith’s brand is about is bringing people together," she said, speaking of herself in the third person, as basketball superstars do on occasion. "I think that if Martha Stewart and Oprah had a daughter, it would be B. Smith,” she told National Public Radio in 2007. The success and resolve of Katherine Johnson and B. Smith, as they ignored stereotypes, would be inspiring anytime. In Black History Month, the accounts of their accomplished lives lit up my day. * * * (The obits are too long to reproduce here, so I am enclosing the links to the NYT website. People who do not subscribe can pull up a certain amount of free links per month. Other obits of these two achievers will surely be on the web -- GV.) Katherine Johnson: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/science/katherine-johnson-dead.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage B. Smith: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/23/obituaries/b-smith-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1 Back in the day, when sports columnists were a daily presence, my job description included having an opinion on the national college football championship. Often, this entailed being in warm places on New Year’s Day, which is the best thing I can say about covering the loopy methods of judging teams with differing schedules playing in different bowl games. Bowl games got me to Pasadena or Miami. What can I say? Now that I am retired, I pay no attention to any form of football. Instead, I am free to follow another highly imperfect ratings system, closer to my heart and ear – the annual vote for the best classical music, as conducted by the invaluable station emanating from my home town (and live on the Web) WQXR-FM, 105.9 on the dial. The station has been conducting this poll since the mid-‘80s, asking listeners to rank their favorites. The results are played in the annual countdown in the last week of the year, generally reflecting the programming of the station – the old favorites, often presented one movement at a time. During the countdown, the station also conducts a running blog (results not updated as quickly as listeners would like) including commentary from the faithful in distant states and foreign lands. Many of respondents are passionate about wanting" More variety! More medieval music! More Reich and Glass! More music by African-American composers! More music by women! Plus, there is the rampant suspicion that some Gilbert & Sullivan supporters pack the ballot box, just like voters in some towns and states I could name. And some listeners question whether Gilbert & Sullivan is actually classical music. I pass on that one. My feeling is, the annual countdown reflects the tastes of people who support WQXR and live classical music in New York. More power to them. Still: every year I make a small list of music I play at home, and I hope some of it will slip into the countdown. As my friend Vic Ziegel, who introduced me to the strange charm of the racetrack, used to say about the track announcer: “At least give my horse a call.” In the past few couple of years, I have been trending toward chamber music at home because it is self-contained, providing a welcome alternative to the toxic earworms on the air waves. --In an ugly time, I have become infatuated with Ravel’s “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” for its beauty and pace and dignity. --I often choose “Butterworth/Parry/Bridge,” its three composers taking me back me to lazy summer days, visiting a friend in the Brecon Beacons of Wales. -- I was rooting hard for something by Florence Price, the composer whose work is often championed by the wonderful Terrance McKnight on his evening gig, not just in Black History Month, either. --Because we are blessed to have two good friends comprising half of the New Zealand String Quartet, we have their works by Bartok, among others. -- But the work I was really hoping for was Sir William Walton’s Violin Concerto, performed by Kyung-Wha Chung. I still remember the first time I heard it: I was a news reporter in the late ‘70s, driving to meet some nuns in jeans and sweatshirts who did the Lord’s work in the South Bronx. But when this stunning piece appeared on my car radio, I sat and listened for the full half hour. Alas, this beautiful piece is not easily found on vinyl or CD – and is not in the WQXR top 120, either. Not even, in racetrack parlance, a call. The 2019 list does include many things I love, including a few pieces by Erik Satie, Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings,” and – No. 4 in the poll -- Dvorak’s “From the New World.” The older I get, the more I appreciate Dvorak, for his music and also for his love for two worlds, Bohemia and America. I missed it live, but there on the list at No. 68 was a very modern already-classic, "The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace," by Karl Jenkins, first performed in 2000, which I heard for the first time in the past year. However, the piece that really knocked me out was No. 109, Gustav Mahler’s “Symphony No. 8 in E-Flat, Symphony of a Thousand,” by the San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas conducting, with wonderful soloists and choruses. It made me stop what I was doing and just listen. At the end, Beethoven placed six in the top 10. I have no quarrel with the selections because the voters care about “their” music. It’s up to us to seek out the music we love, and play it, and pay for it, early and often. Happy New Year. * * * The current results: https://www.wqxr.org/story/wqxr-classical-countdown-2019/ Plus, check out the blog with informed and passionate comments by listeners: . And for comparison, the two most recent results. https://www.wqxr.org/story/wqxr-2018-classical-countdown/ https://www.wqxr.org/story/wqxr-2017-classical-countdown/  In this ugly time, I tear up when reminded of the knowledge, the eloquence, the idealism of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama. Sometimes, I entertain the fantasy that Mrs. Obama will offer herself as a candidate for President – not that I would subject her, or her family, to the viciousness of another campaign, another presidency. Besides, any ephemeral hopes have been dashed by reading Mrs. Obama’s stimulating book, “Becoming,” which confirms what has seemed apparent: since she was young, Mrs. Obama has felt a visceral distaste for politics. In her book, she recalls qualifying for the elite Whitney M. Young Magnet High School, which entails a long two-bus commute, but also introduces her to new friends like Santita Jackson. Sometimes, after school, she is invited to the Jackson home, which takes on a frenzy when the man of the house, Jesse Jackson, is in town, making plans for one campaign or another. One day Michelle and Santita find themselves “conscripted” into marching in the annual Bud Billiken Day Parade on the South Side. “The fanfare was fun and even intoxicating, but there was something about it, and about politics in general, that made me queasy,” she writes. When she comes home that afternoon, her mother, the stalwart Marian Shields Robinson, is laughing, saying: “I just saw you on TV."  Michelle Robinson Obama has always known her own mind. She was enough of a realist to admit that she had fallen for a charismatic summer intern at the law firm she had worked so hard to join. Barack Obama had many plans and dreams, and in her telling, she had enough faith in him that she would change her own life around. That is the first half of the book – how Michelle was raised by Fraser and Marian Robinson, and her older brother, Craig, a basketball star at Princeton, and strong-willed, talented relatives. The richness of her family life – the wisdom of her parents – challenges any stereotypes of African-American life that might get thrown back at the Obamas, to this day. The second part of the book is about Michelle Obama’s reactions to her husband’s abrupt rise to presidential candidate. Mrs. Obama describes how campaign aides failed to prep her for public appearances, leaving her to improvise. She realized she was no longer primarily a lawyer or community organizer but a political spouse who can jangle a campaign with one impromptu phrase. A born organizer, she seems to have impressed upon the handlers: That won’t happen again. She describes election night in 2008, when her husband, seemingly so confident, watched on television, and how her mother reached out and patted his shoulder. Mrs. Obama describes how much she already admired Laura Bush from afar, for her poise and advocacy of books. During the transition, she quickly came to like Mrs. Bush’s husband, and has often been photographed hugging and laughing with him.

She describes life in the White House, how close the family – including her mom -- felt to the mostly-black staff, and how much she relied on advisors to help with her interest in nutrition and gardening and with her wardrobe. She praises the President as a loyal husband and father. I know this is true because a journalist friend of mine, who often traveled on the Presidential plane, told me how day trips were planned to get the entourage back to Washington in time for the Obamas’ 6 PM supper in the White House. How Michelle Obama really felt about being a White House wife comes out in one of the most charming anecdotes in the book: On the evening of the Supreme Court ruling in favor of gay marriage, large crowds celebrated in front of the White House. Michelle and her older daughter, Malia, made a break for it, rushing past their guardians, finding an exit to a quiet corner of the garden, just to feel and hear the jubilant crowd. For a few minutes, they beat the system. There are many sweet memories in this book (written with the help of a talented journalist, Sara Corbett): the entire family meeting an elderly Nelson Mandela in his home, and feeling so comfortable with Queen Elizabeth, who motions for Michelle to sit next to her, referring to palace protocol as “rubbish.” The book includes gracious mentions of all the people who helped her, and minimal references to the candidate who tried to portray her husband as an illegal alien. I would have liked to hear what Michelle Obama really thinks of that man, but the Obamas live by smart lawyerly aphorisms: “Don’t do stupid stuff.” And “When they go low, we go high.” In its high-minded way, Michelle Obama’s book reminds me that this family has earned its independence, mostly out of the spotlight. We were lucky to have them. The present is superimposed over the past. The U.S. Open began Monday by doing the right thing. A statue of Althea Gibson, pioneer and champion, was unveiled at the National Tennis Center, where she never played, at least competitively. Billie Jean King, Zina Garrison, Leslie Allen, Katrina Adams and Angela Buxton, Gibson's old doubles partner, all spoke of how Buxton was first. The statue, by Eric Goulder, is striking, as was Althea Gibson. Buxton, 85 and in a wheelchair, flew from London to recall how she bonded with Gibson on a pioneering mixed tennis trip to India and other countries. This belated honor to the first African-American player to play -- and win -- the "national" tournament is a prime example that this grand New York event is never only about these few weeks. The Open is about continuity. For all the crass, hard edges to the contemporary Open, there is still a faint whiff of gentility from the old Nationals in Forest Hills. Maybe it was the grass and the clubby atmosphere that mellowed people out. While tennis patrons this year are eager to catch a glimpse of Cori Gauff, age 15, to see if she just might be “the next” Naomi Osaka, or “the next” Sloane Stephens, the old champions still grace this event, in person or in perpetuity. I think of them every year as I visit the Open. I was reminded of Gibson this past week when Art Seitz, long-time tennis photographer from Florida, sent photos of Gibson that he had taken over the years. Seitz said he often met Gibson and found her to be friendly within the tennis circle, particularly to the young players, as tennis evolved to the age of King to Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graf and Venus Williams and Serena Williams and so many others.  Power and form: Althea Gibson serving in Florida, after her career. Photo: Art Seitz Power and form: Althea Gibson serving in Florida, after her career. Photo: Art Seitz The old champions are part of the Open, and so is the old site -- Forest Hills from 1915 through 1977. As a Queens kid of 10 or 11, I started taking the IND subway to 71st St/Continental Ave., walking to the little oasis of the West Side Tennis Club. The place was so tiny, so intimate, that you could literally rub shoulders with players as they tried, politely of course, to reach their grass court for a match. As a Brooklyn Dodger/Jackie Robinson fan, I was eager for glimpses of Althea Gibson, the first African-American to play in the “national” tournament. She made her debut in 1950 and did not last long those first few years, but her athleticism and drive were obvious. She reached the finals in 1956 and won it in 1957 and 1958, after which she retired from tennis so she could make some money, as incongruous as that sounds today. Gibson played professional golf and I think I saw her play as part of the Harlem Globetrotters tour that came to New York every March. But money never reached Althea Gibson as tennis became big business, and old stars often returned to add their luster to the event. As a columnist who covered the Open and often Wimbledon, too, I was never aware of Gibson giving a press conference or showing up for big-bucks from sponsors and patrons. Except to get Gibson's autograph a time or two on the crowded walkways of the West Side Tennis Club, to my regret, I never met her. The best reflection of Gibson on Monday came from Buxton, a British player in the '40s and '50s, who had eagerly played doubles with Gibson, winning the 1956 Wimbledon doubles. Buxton said that as a Jew she was also somewhat of an outsider in those years. Buxton told the crowd at the unveiling how her family in London was host to Gibson when she played Wimbledon, and how Buxton's mother introduced the two players as "my daughters." In recent decades, Buxton would come around and chat with reporters, with obvious affection and a sense of mission about her friend Althea. In 2003, she told a reporter that Gibson was "tall and lanky and rather like Venus Williams.” Gibson was said to wish the Williams sisters, as great as they are, would rush the net more, but that is contemporary tennis. articIn later years, Gibson was ill, at home in New Jersey. She passed in 2003.

The city of Newark has put a statue of Gibson in a park, and now the USTA, through the of efforts of Katrina Adams, a former player and recently the president of the USTA. The talent and will of Althea Gibson are part of the Open, reflected by the current players, most of them tall and agile, like Gibson. We follow the new stars, and Althea Gibson’s image is with us forever -- on the lawns of the sedate little club a few miles away in another corner of Queens. * * * Obit, NYT, 2003: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/28/obituaries/althea-gibson-first-black-wimbledon-champion-dies-at-76.html?searchResultPosition=2 Current NYT article on the statue and how it got here: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/26/sports/tennis/althea-gibson-statue-us-open.html A Florida reporter's perspective of Gibson: https://www.nydailynews.com/os-xpm-2003-09-29-0309290251-story.html Gibson and "the Nationals" and Queens: https://www.6sqft.com/67-years-ago-in-queens-althea-gibson-became-the-first-african-american-on-a-u-s-tennis-tour/ The Facebook site for Art Seitz: https://www.facebook.com/ArtSeitz I was busy working on something else when I heard about Alvin Jackson Monday, so I kept going, with a heavy heart. Then I received emails from three pals, one an old ball player from Brooklyn saying, “From what I know, he was a class guy,” and one e-friend from West Virginia saying, “He sounds like a fine fellow,” and one pal at the Times, saying “I’m sure you knew him.”

Yes, I knew Alvin Jackson from April of 1962, knew him from games he won and games he lost, and I also knew him as a wide receiver in touch football. True. You can read the lovely obit in the Times and learn a lot of the details of his life: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/sports/baseball/al-jackson-dead.html I was a young sportswriter in 1962, first year I traveled. Jackson was a steady pitcher on a team that lost 120 of 160 games. Casey liked him for himself and also because Casey, who was childless, was proud of the Mets' considerable number of "university men," many of them pitchers. By Casey's standards, Jackson was a university man, but Jackson could also keep the ball low and he never lost his poise. When we interviewed Alvin after losses, he kept it inside, which I attributed it to the caution of a black man from Waco, Tex., who has learned not to show too much of himself. He also had occasional whooping laugh that he allowed to escape. We never got serious about much, but on Aug. 28, 1963, I watched Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech from the Mall in Washington, on the TV in my hotel room in Pittsburgh, and when I went down to catch the team bus to the ball park, I got into a conversation with Alvin and Jesse Gonder, the catcher, and Maury Allen of the (good old) New York Post. We agreed that something momentous had happened that day and I felt we all had gotten a glimpse of the others’ heart. https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-day-i-watched-dr-king-and-the-mets Alvin was living on Long Island in the off-season, and one of my colleagues at Newsday mentioned that we played touch football once or twice a week at a park in Hempstead. Jackson and most players had the same economic level as reporters, so sometimes he worked at a winter job, but most game days he showed up, ready for a run, ready to break a sweat. In 1963, another Met, Larry Bearnarth, who was living nearby, joined the game. They got their tension during the season. What they wanted was a workout. They never big-timed us, tried to call plays or ask for the ball. Joe Donnelly, who had a great arm, and I, who had no arm at all, were usually the quarterbacks. Let me say, it was a trip to be in a mini-huddle, calling a play involving somebody who pitched in the major leagues. I think Alvin and Larry were in the game on Nov. 22, 1963, when the fiancée of one of the players came running across the parking lot and delivered the terrible news. We all just went home. By 1964 Alvin was a club elder: "Wonderful gentleman," Bill Wakefield, a very useful pitcher on that squad, wrote to me in an e-mail. "He was very nice to me. Treated me (a rookie) like I was a veteran of the original Mets vintage. Great smile and laugh! Good pitcher. Not overpowering stuff, but knew how to pitch. Good guy." Jackson pitched one of the most masterful games of that first Mets era on the final Friday of the season, in St. Louis: He shut out the Cardinals, who were fighting for the pennant, by a 1-0 score, bringing the chill of winter into the city, but the Cardinals survived on the final day. https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B10020SLN1964.htm As Alvin’s career dwindled, he moved on, and then he was a pitching instructor for various organizations, including the Mets in later years. When we ran into each other, he was cordial; not all ball players remember your face. Once in a while, I would see him and make the motion of a quarterback throwing long, and he would give his whooping laugh, not needing to add, “as if you could.” He stayed on Long Island a long time. I never knew that his wife, Nadine, a lovely presence, was the chairwoman of a business department in a Suffolk high school. I just knew they were a dignified couple -- a university man and woman. Alvin Jackson brought dignity and discipline that rubbed off on teammates, on reporters in the locker room, and even on fans who could tell, from a distance, that he was indeed a very nice guy. I learned something very nice today.