|

"There are 9,388 graves in the cemetery, most of them in the form of white Latin crosses, a handful of them Stars of David commemorating Jewish American service members. As antisemitism rises again in Europe, they seem somehow more conspicuous." ---Roger Cohen, The New York Times. "D-Day at 80" -- June 6, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/06/world/europe/dday-80th-anniversary-veterans-remember.html Marianne Vecsey noticed the same thing, back in the mid-70s, when we drove with our young children to Normandy, in the sweet damp spring. Part of Marianne's ancestry goes back a thousand years to Normandy, but this was not about us. This was about the Allies who died during the invasion, now 80 years ago. We live in New York; we tend to notice stars amidst the crosses. "You hear the number, but when you stand there, and see the graves with crosses and stars, it sinks in. It's stunning, actually," Marianne said on D-Day 2024. Roger Cohen had the same reaction. Of course he did. Roger is one of the greatest Times writers of any generation -- fearless, perceptive, the voice of the underdog, the champion of the fallen. I've spent great times with Roger running around Germany during the 2006 World Cup or watching him suffer for his Chelsea F.C., in some New York pub. I've read his poignant tribute to his mother, to all who suffer, in his 2015 book, "The Girl From Human Street." https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/22/the-girl-from-human-street-review-roger-cohen-memoir-motherodyssey-of-loss I miss him in New York -- Brooklyn, to be specific, but now he is right where he should be, in the middle of it, as Paris Bureau Chief, preparing his masterful text for the 80th "anniversary." Marianne and I and "the kids" made the same pilgrimmage north from Paris, borrowing a friend's chugging sedan, heading toward the tangy air of salt water, toward Mt. St. Michel. (I had learned to love Mt. St. Michel, reading Richard Halliburton in grade school.) Now we were there, in a scruffy little gite near the beaches, in a spring so damp that sheets did not dry on the line. We saw the Bayeux Tapestry, of course we did, and then we headed to the beach. Funny, as we sat atop one of the sandy cliffs, we heard distinct German voices behind us -- three cars, three sporty couples, no longer the enemy, just modern Europeans on spring holiday, to see the Normandy beaches, the landing now three decades in the past. We took in the logistics of that landing, what it was like to be in those landing craft. The only person I knew who had been in one of those boats was Lawrence Peter Berra of St. Louis; but Yogi never talked about it, just as his teammate Ralph Houk barely alluded to his battlefield commission at the Battle of the Bulge. Veterans don't talk much. Marianne learned that when she was a lifeguard at a village pool on Long Island. Some of the older town workers had been in the war, but never shared details. Now it is 80 years, and centenarians will talk, particularly if a master journalist like Roger Cohen asks the right questions, the right way. People talk to Roger. Read his words; look at the photos. Marianne stored the visual memories, the visceral impact, of the Stars and the Crosses. She's an artist -- has a lifetime of paintings out there.

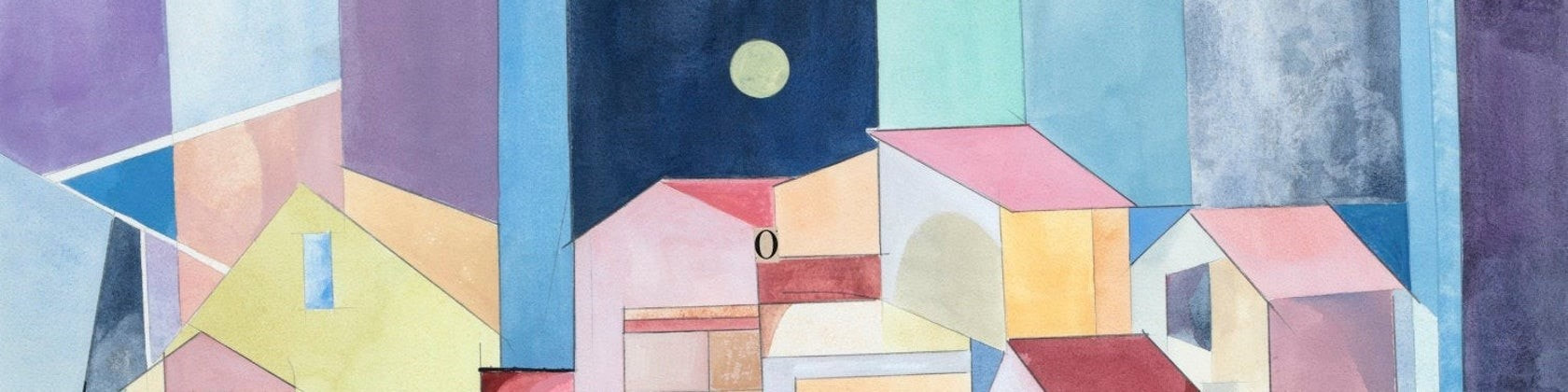

We loved our April in Paris, staying in a sous-sol in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The Metro. The Louvre. The Bois. Then we came home and resumed normal lives, and one night Marianne waited for the family to go to sleep, and she painted her geometric tribute. This month Roger Cohen has been, as always, in the right place, recalling the Canadians, the Europeans, the Americans, who stayed behind, in Normandy. Happy Father’s Day…Best Wishes at Juneteenth….and hopes for a good and healthy summer for all.

My first present – there are others – was a lovely essay in The New York Times written by one David Vecsey. The essay proved (once again, to me) that it is hard for me, being the least talented and versatile among the five members of our family. Marianne is an artist (more on that momentarily) and has a dozen other skills. Laura was a poet first and then a really good news reporter and sports columnist at four major papers around the country, and is now a real-estate maven upstate. Corinna worked in journalism (in Paris, later in New York) and is now a lawyer and consultant to feelgood projects in Pennsylvania. David could have (should have) been a sports columnist but after some time in the Web world, he learned newspaper editing from some good teachers at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and passed the editing test and tryout at the Times a decade ago, to our delighted surprise. So….a father and husband can brag on Father’s Day. My wife did it all. As David attests in his story, I was at the ballpark or typing in my room, putting in an appearance for meals or a catch or hoops or maybe a drive to Jones Beach or the city. I did take each of them with me on road trips to deepest America, not for games but for real life. Marianne did the hard work, the parenting. And it shows. They are all good parents. They all can cook. They all have spouses, Diane and Peter and Joelle, who match them, skill for skill, energy for energy, will for will, value for value. How blessed we are. David is usually busy putting the last bit of polish on articles for the Print Hub (that is to say, “the paper.”) He’s been working at home the past year, and instead of riding the railroad he has been able to develop other corners of his brain. In his younger days, he watched his mother cook, and sometimes went to the New York Philharmonic with her when I was away. He also watched her paint, in her “spare time,” late at night, her newest work materializing when we woke up in the morning. Over the years, she won prizes, appeared in nice shows and galleries, sold around 300 paintings, some of them now around the world. Recently, David asked if she had slides of her work, and yes, she had some tucked here and there. So he commandeered the slides, put them through the magic visual part of his computer, and turned some of them into posters and greeting cards, with themes and connections only his active mind could make. He has put them online, displayed them at crafts shows on Long Island, placed them in some nice shops, mailed the work to Berlin, to England, and corners of the U.S. It’s all on a very modest scale, and by Dave’s decree, some of the money is going to charity. The point was never money, it was the art, the work, the product, the result. I sit back and enjoy the smartphone pings from our scattered family. They are the best gift, on Father’s Day. * * * You should be able to open David’s story online today: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/19/insider/george-vecsey-fathers-day.html?searchResultPosition=1 For information on David’s project, Marianne’s work: https://www.etsy.com/shop/vecseyprinthub/ For many years, Marianne painted in the midnight hours, when the kids were asleep and I was on the road somewhere. After a few hours of sleep, she got up and made school lunches and checked her lesson plans and drove off to teach art.

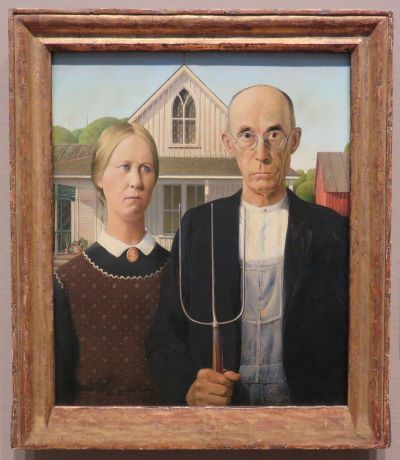

At some point she produced this large painting, which wound up in a gallery in Manhattan, and then in friends’ apartment on the Upper East Side. But now those friends are downsizing, and no longer have room for the painting, so they graciously offered it back to the artist. In the middle of a pandemic, with no station wagon anymore, we did not see retrieving it and squeezing it into our house, already crammed with books and art and kitchen utensils. Marianne mentioned her dilemma to our West Side friends, who are redecorating their apartment in the 50s. They know her work, and were interested, but the painting had been wrapped, and was sequestered in the basement of the East Side building. So they accepted it, sight unseen. Then came moving day, part of the daily buzz of the city, good times or bad times -- folks clutching modest bags of clothing on the subway, other folks engaging gigantic moving vans that block side streets, out-of-town children of privilege who come clumping down the elevated train stairs with one wheeled suitcase in an “emerging” neighborhood, getting dirty looks from ladies in the local peluqeria whose rents are about to double. (I witnessed that in Bushwick two years ago.) Now our friends were joining the sidewalk shuffle, taking 45 minutes to walk across town, spotting “dog runners and dog strollers in the park, empty buses plying Fifth, a fit couple racing up and down the Met Museum’s steps. The ‘Ancient Playground” at 85th and Fifth still temporarily closed,’” as the lady half of the couple wrote. I had warned that if they tried to carry the painting across town, one of those classic crosswinds that scream out of a side street could pick them up, clutching the painting, and deposit them in Oz, or New Jersey. But it did not come to that, because when the East Side porter delivered the 6-by 4-foot package near the front door, they realized it was so sturdy that blithely carrying it across town – for fun, for exercise – was out of the question. Now began the quest for wheels. They tried shoe-horning it into a city taxi, but it was four inches too long, so they tipped the driver for his effort, and waved farewell. The super helped them carry it to a busy corner and left them to their adventure. They hailed two panel trucks and tried to cajole the drivers into making an excursion, but both apologized for being busy. A plumber parked nearby offered to help but needed an hour to set up his crew. Tired of standing on the corner propping up a large painting, they called a messenger service, New York Minute, which promised to drop it at their building, as they took a taxi back home. An hour later, the painting arrived and they set it on the terrace for a few hours to give germs time to die. They still had not seen the painting that had occupied several weeks of logistics that could have sent a spaceship to a far-off docking station. (Did I mention that Marianne, in her other life as matchmaker, a/k/a the shiksa shadchen, had matched these two friends, not so long ago?) “Unwrapped, it was love at first sight. It’s Marianne’s Geometric Period, mixed media watercolor and oil,” our friend reported. “It miraculously fit on the pre-existing hooks opposite our bed.” They took a photo – the miracle of the smartphone—and beamed it to Marianne, who immediately recognized it from the period, decades ago, when she found a makeshift table that could accommodate larger canvases. She has sold around 250 paintings, some now dispersed around the world. She may not recall the year or the circumstances of each painting, but she recognizes each painting, remembers the creation. She has won awards in juried shows, has placed her work in slide form or real-life form, in Manhattan galleries, has received respectful “keep-painting” receptions from major galleries, some of them part of the art hustle of recent decades, no names mentioned. It all came back to her, including the review in NYT’s Long Island Section, by critic Phyllis Braff: One feels and imagines the aura of the Grand Canyon, Notre Dame, a night sky, a fall landscape or a cemetery in visions that are executed through rather innovative manipulations of small squares made vibrant with mottled, transparent watercolor tones. Color selections that tend to be symbolic, and exacting schemes of dispersing the painted units, are both important in carrying the message. This painting, part of Marianne’s most active period, is now hanging in the bedroom of a fashionable apartment, home to many soirees with art-conscious New Yorkers. But the main reward came when the lady wrote: The painting is now the last the last thing we see at night, and the first thing we see in the morning. Joy. Marianne’s painting has made the daunting crosstown trek from the East Side to the West Side. Its journey has also brought us joy. * * * The review in the NYT by critic Phyllis Braff: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/09/nyregion/art-unexpected-messages-in-geomettic-form.html?searchResultPosition=1 (The following ode to Iowa was written before all hell broke loose in the ramshackle "system" that was supposed to collate the Democratic caucus results Monday night. Even before the network failed to produce while the world was watching, visiting savants like Chris Matthews were questioning -- in front of the earnest citizens -- why Iowa got to hold the highly visible first "primary" scrimmage every four years. With these reasonable questions being raised, Iowa may lose its prominent spot. Shame. There ought to be a place for well-meaning Americana -- but maybe not with an ignorant and vicious wannabe dictator getting a free pass from his party enablers. Poor Iowa, caught up in the tumult. My original praise for Iowa and skepticism about a caucus:) They are highly motivated, conscientious American citizens. But what in the world are they doing? Why don’t they just vote? Then I remember, Iowa is different, or so they say. I’ve been there three times and liked all three visits. (More in a bit.) While trying to make sense of this caucus thing Monday evening, I remembered one of my favorite musicals – “The Music Man,” by Meredith Willson, that’s with two L’s, and don’t you forget it. A con man (Robert Preston) gets off the train in River City, Iowa (Willson was from Mason City) and tries to chat up the townspeople, only to receive a bunch of double talk, some of it polite. The result: “Iowa Stubborn.” That charming character trait emerged Monday in snow-covered Iowa (or “I-oh-way,” as some of the denizens insist.) “The caucus is like cricket,” I told my wife. (We once saw the great West Indies team play a tuneup in a Welsh country town.) “Cricket is easier,” she said, meaning – bat, ball, tea. This caucus thing determines who wins the delegates, who has the momentum, or maybe not. It’s a portrait of Iowa. The Grant Wood painting, American Gothic. I am affectionate about Iowa – after first noting that its populace does not at all resemble that of my home town of New York. My first trip to Iowa was in 1973 when Charlotte Curtis, the great Family/Style editor of the Times (herself a Midwesterner), sent me out to Iowa to write about a boy, 18 or 19, who had just been elected mayor of a little town. (I cannot find the story in the electronic files.) It was such a nice visit, at this cold time of year, as I recall. My second trip to Iowa was early in 1979 when Iowa was selected as one of the sites for the first American visit by Pope John Paul II, because of the huge farm preserve, judged a perfect site for the man from Cracow. After scouting out Des Moines, I had dinner with a couple who had met when he was posted to her town in the Altiplano of a South American country. We went to a Chinese restaurant, where they chatted with the staff in Spanish – a big Chinese contingent, emigrated via Latin America. My third trip to Iowa was on a perfect autumn day in 1979 as the square-jawed Pope strode the plains, waving to a bunch of Lutherans. He was young and strong, looking like a former linebacker for the Iowa Hawkeyes. I edged closer to get a look – and got blind-sided by an American Secret Service guy. When the Pope had moved on, I stood on the great plain and congratulated the nun who had facilitated the press visit. She was so happy that the day had turned out so beautifully that I could think of only one thing to do – I hugged the nun. That’s what I think about whenever I remember that day. Oh, one other Iowa impression: Our daughter Laura decided to spend her junior year abroad and chose Iowa City. Every few weeks the phone would ring and a plaintive voice would say: "It's dark out here."  "American Gothic," by Grant Wood. From the Art Institute of Chicago. My feet can find it whenever I climb the front steps. "American Gothic," by Grant Wood. From the Art Institute of Chicago. My feet can find it whenever I climb the front steps. Now, every four years, the great journalists from my cable-network-of-choice wander all over that state and I thrill to every coffee klatsch and every barber shop. The journalists can explain “quid-pro-quo” and “impeachment” perfectly, but they cannot explain what those folks are doing on the first Monday in February. (The aforementioned Laura watched caucus news from Iowa Monday night and texted us: "Nicolle and Rachel far better than Troy and Buck." Poor girl is having Super Bowl flashbacks.) Maybe Meredith Willson could have explained the caucus, but he was more interested in the busy intersection of chicanery and romance, and bless his heart for that. There is a current art exhibit in Washington, D.C., that I am hoping to see -- “Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975,” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

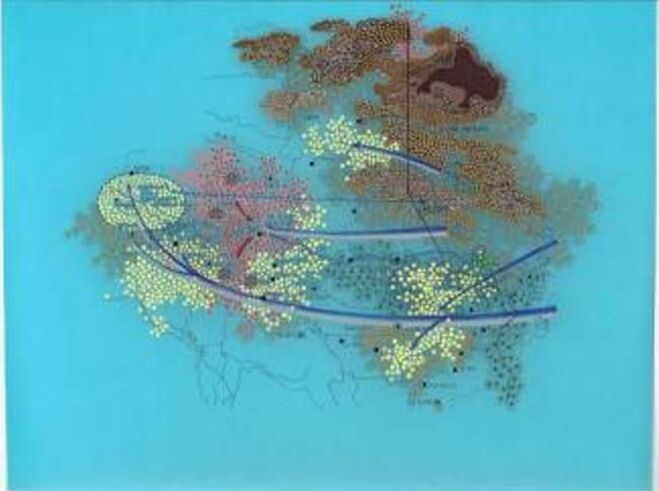

Holland Cotter in The New York Times calls it “protest art” from the American point of view. But the “second, smaller” part of the show I most want to see is “Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past Is Prologue,” a view of the Vietnam War era through Vietnamese eyes – “far more than a mere add-on,” as Cotter put it. The Vietnamese people experienced that war – in some ways 180 degrees differently -- but it is safe to say all suffered. In 1991 I visited “post-war” Vietnam with a small group involved in child care. My wife was doing vital volunteer work by frequently visiting India but she also visited Thailand and the Philippines. I joined her on the trip to Vietnam to deliver goods to a hospital and visit facilities in both “North” and “South” Vietnam. I was most definitely not there to work or act like a journalist, but I could not help looking and listening to how “The American War” had impacted Vietnamese lives. Saigon, now called Ho Chi Minh City: We met a doctor doing complicated surgery. He let us gown up and observe a complicated facial procedure done by a visiting American doctor, the mutual language in the operating room being French. We got to spend enough time with the doctor to learn he had been on the “wrong” side when the North took over, and was sent to a camp deep in the countryside. I gathered that his family had assets, and he had a great reputation, and he was released from the camp and allowed to resume his profession, refreshing his skills at major hospitals in Asia. He was an asset. In a relaxed social setting, the conversation got around to how he was able to put the war behind him, to function, to move on. I totally paraphrase his answer; it has been a long time, after all. He said you cannot live in the past, you have to get back to “normal” as smoothly and quickly as possible. When I (subtly, I hope) asked about the lost years in the camps, he showed no bitterness. He was still a surgeon, putting people back together again. Life went on. Hanoi Region. We worked our way up north (baguettes and coffee on the beach; ancient ethnic villages; a growing crafts shop outside Da Nang) and we flew to Hanoi. On a chilly day, we took a jitney out to visit a rural orphanage. Our interpreter was a woman around 30 who worked in the sciences and was fluent in English. I happened to sit next to her. Far into the countryside, I noticed circular ponds scattered on the flat land. I asked the interpreter what the waterholes were for – fishing? rice? source of irrigation? Actually, she said, with no trace of emotion or agenda, they were holes left over from bombs. She did not mention Richard Nixon or Henry Kissinger or the “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi and Haiphong in late December of 1972. She remembered, she said casually, living at a school, and hearing the bombs, and later discovering children her age had been killed or injured. I did not ask any other questions. The orphanage was shabby, but the workers were doing the best they could. They let us hold children as we walked around. They had a handle on each child, would not release children for adoption if relatives claimed them. We were bringing some aid, and people were courteous. A young worker pointed at my ball cap, from the 1990 World Cup, and he said, “Maradona,” and I gave him the cap. And then we flew on. Now I read about the show at the Smithsonian about the remaining terrible divisions in the United States over the Vietnam War. I hope to see that show, as well as its companion piece about Vietnamese reaction to the American War – “more than an add-on,” indeed. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/04/arts/design/vietnam-war-american-art-review-smithsonian.html Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past Is Prologue: https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/chung My past articles about John McCain, American hero, and Vietnam: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/category/vietnam My article about the excellent crafts shop outside Da Nang: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/-happy-lunar-new-year My birth-date pal, John McDermott, ex-difensore del club Italo-Americano di San Francisco, is better known as master photographer of subjects moving and still.

Not to stereotype him, but he is at his best covering the world sport of soccer. (Yes, that is Roby Baggio's voice on his cellphone.) John is now living in Italy, making art out of the Dolomites and the streets of Napoli. He recently put together the video above for a sports seminar he was giving in Verona. You will recognize Maradona, Baggio, Beckham, Klinsmann, Ronaldo, plus Olympic sports. Click it on, above. * * * Lonnie Shalton is a financial-services lawyer in Kansas City who issues occasional sports blogs that never fail to entertain and stimulate me. (I know him through Bill Wakefield, the Kansas City kid who had a very nice 1964 season for the NY Mets.) Lonnie's latest, in honor of the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr, is about Negro League Baseball, a passion of his. On this blog, he presents the history,with photographs, of the only woman selected for the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Hot Stove #90 - Martin Luther King Jr. Day (2019) - Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles Lonnie Shalton [When my law firm added Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday in 2002, I began an annual message within the firm about why we celebrate the holiday. The distribution was later expanded outside the firm, and since 2016 the message has been circulated as a Hot Stove post. Below, my 18th annual MLK message.] One of the best ways to appreciate Martin Luther King Jr. Day is to visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Not just for the memorabilia collection – although that is well worth the trip. There is also a compelling civil rights lesson. As one walks through the baseball exhibits, there is a parallel timeline along the lower edge that places Negro Leagues history in context with civil rights milestones. In a new exhibit added last year – “Beauty of the Game” – the museum honors the contribution of women both on and off the field. The exhibit features three women who played in the Negro Leagues (Mamie “Peanuts” Johnson, Toni Stone and Connie Morgan), plus one executive, Effa Manley. Effa Manley is also featured in another well-known museum. She is the only woman ever inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. There are 324 men. Below is her plaque at Cooperstown: Abe and Effa: Effa Louise Brooks grew up in Philadelphia and moved to Harlem after graduating from high school in 1916. She met Abe Manley in the early 1930’s and they married in 1933. They were both baseball fans. Effa went to games at Yankee Stadium (“I was crazy about Babe Ruth”). Abe went to Negro League games when he lived in Pennsylvania and became friends with many of the players. He also once owned a semipro team. Legend has it that Abe and Effa met at Yankee Stadium during the 1932 World Series. Effa and Abe each brought an interesting backstory. Effa’s maternal grandparents were German and Native American. Her father might have been her mother’s black husband or white boss. Whatever the correct story, Effa lived her life as a black woman married to a black man (actually four, the marriage to Abe plus three short-termers). Abe was in the numbers racket and some of his excess funds would come in handy to own a baseball team. At least two other Negro League teams were similarly capitalized – it’s not like there was a lot spare capital in the black community. Negro National League (NNL): The original Negro National League was formed in 1920 at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City. The KC Monarchs joined the league and became one of its premier teams. The league was forced to disband during the Depression, but it was revived in 1933. However, the Monarchs did not rejoin, but instead became a member of the new Negro American League (NAL) formed in 1937. In 1935, Abe Manley formed the Brooklyn Eagles as a franchise in the NNL. He moved the team to Newark the following year, and the team played as the Newark Eagles from 1936 to 1948. Effa became Abe’s partner in the business and soon took over the day-to-day operations. Abe liked the social side – traveling with the players and swapping stories – the team was his “hobby” according to Effa. She did almost everything else: setting playing schedules, booking travel, managing payroll, buying equipment, negotiating contracts, dealing with the press and handling publicity. She was a trailblazer on creative promotions to draw fans. She was also very active in the community and counselled her players to do the same. She became the public face of the Eagles. Effa was also an active participant in league matters. There, not to the pleasure of some owners, she was outspoken and demanding. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords (and, like Abe, a numbers runner), was president of the league in the early years. His initial take on Effa: “The proper place for women is by the fireside, not functioning in positions to which their husbands have been elected.” Sportswriter Dan Burly wrote that Effa was a “sore spot” with other owners “who have complained often and loudly that ‘baseball ain’t no place for no woman. We can’t even cuss her out.’” Greenlee learned to deal with Effa, and this leads to a Satchel Paige story. In Larry Tye’s biography of Satchel, the author writes that “[Effa] also was renowned across blackball for her willingness to battle on behalf of both the Newark Eagles and civil rights, her pioneering role as the sole woman of consequence in the fraternity of the Negro Leagues, and her flirtations and more with her husband’s ballplayers.” It is that last item that lends some context to the Satchel story. Paige had played for Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1936 and then jumped to a Dominican Republic team for 1937. He was potentially returning to the states in 1938, but Greenlee was tired of chasing him and sold his contract to the Eagles. As Effa told the story in a 1977 interview, “Satchel wrote me and told me he’d come to the team if I’d be his girlfriend…I was kind of cute then too…I didn’t even answer his letter.” Satchel’s letter was a little ambiguous: “I am yours for the asking if it can be possible for me to get there…I am a man tell me just what you want to know, and please answer the things I ask you.” Satchel instead pitched in Mexico in 1938 and never joined the Eagles. But Effa’s role was memorialized in the press: Effa became a force in the league. She pushed for a more businesslike operation and rules to deter players from jumping teams. She argued for an outside commissioner. Her hard work and perseverance brought a grudging respect. In the end, as shown in the photo below, she was “in the room where it happens.” Effa as Civil Rights and Community Activist: Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. came to national attention in 1955 in the bus boycott in Montgomery. That was 21 years after Effa Manley led a civil rights boycott. Effa was an influential member of the local chapter of the NAACP and the Citizens League for Fair Play. In 1934, she spearheaded the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign that called for a boycott of Harlem retail stores that would not hire black clerks. One of the key moments was a pivotal meeting between Citizens League leaders, including Effa, and the owner of Blumstein’s, a major department store. The result was a big success. In April of 1939, Billie Holiday (below) released “Strange Fruit” – the protest song that reenergized the fight for anti-lynching laws. Effa took up the cause that summer with the first of her “Anti-Lynching” days at the ballpark. The ushers wore “Stop Lynching” sashes and collected money from the crowd for anti-lynching causes. [Anti-Lynching Law Update: Since 1901, some 240 attempts have been made in Congress to pass an anti-lynching law. All have failed. In 2005, the Senate issued an apology for its past legislative failures. Lynching is no longer the common form of racist killing, but symbolically, it has remained a blemish. Last month, the Senate unanimously passed an anti-lynching bill – ironically, the presiding officer during the Senate vote was Cindy Hyde-Smith who recently used the term “public hanging” as an “exaggerated expression of regard” for a campaign supporter. The bill was not brought up in the House before the session ended, so the process will need to start again in 2019.] Other civil rights and charitable causes were regularly given fund raising nights at Eagles games. During the war, funds were raised for bonds and relief efforts. Effa recruited or shamed other teams into participating to raise funds for the NAACP, the Red Cross and community hospitals, among others. As a local paper wrote, “She was one of the few blacks who had a little money, and she put some back into the community.” And by her actions if not her words, Effa fought for the equality of women in management long before it was fashionable. The Eagles Players: Abe and Effa’s Eagles had three future Hall of Famers in the infield in the late 1930’s. They were referred to as the “Million Dollar Infield” although this was hyperbole – most players (black or white, stars or not) were not making big money in those days. The first baseman was Mule Suttles, one of the great power hitters in the Negro Leagues. [That’s Mule with Effa below. Effa always dressed fashionably, usually with a fine hat, even at the games. But a photographer talked her into wearing a team cap for this photo op.] The third baseman was Ray Dandridge. It was said that a train could go through his bowlegs, but that a baseball never did. Shortstop Willie Wells was so good that he was touted as a replacement for the Dodgers’ Pee Wee Reese who had been drafted for the war in 1942. It was the right major league team, but the wrong year – the Dodgers would break the color line with Jackie Robinson five years later. Newark continued to add good players who helped the Eagles to mostly winning seasons in the 1940’s. The Million Dollar Infield was joined by four more future Hall of Famers: Leon Day, Biz Mackey, Monte Irvin and Larry Doby. The team won the NNL pennant in 1946 and then beat the NAL Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League World Series. The World Series glory was short lived. The good young ballplayers were being recruited by the majors and the Negro Leagues began to decline. Effa Manley v. Branch Rickey: Even before the successful 1946 season, Effa felt the sting of losing a star to “organized” baseball. After Brooklyn’s Branch Rickey signed the Monarchs’ Jackie Robinson in 1945, his next two big signings were in April of 1946: Roy Campanella of the Baltimore Elite Giants and Don Newcombe of Effa’s Newark Eagles. Robinson made it to the majors in 1947, and the other two soon followed. Effa of course did not like losing good players, but she realized that integration of baseball was a victory for the community. But what rankled her was that Rickey was poaching players without any recognition that Negro League teams had developed the players. She thought compensation was justified, but Rickey refused. Despite some bad press for interfering with the integration of baseball, Effa would not be silenced. And her perseverance paid off. Her stars Larry Doby and Monte Irvin both had feelers from Branch Rickey, but ended up with teams who were willing to compensate the Eagles. Branch Rickey was set to sign Doby, but backed off when Cleveland owner Bill Veeck entered the picture. Rickey knew it would be good to have a second team integrate, especially one in the American League. So Doby signed with the Indians in July of 1947. Veeck knew that Effa had no leverage to get compensation for Doby. But Veeck was no Branch Rickey. The Indians paid $15,000 to the Eagles. More importantly, Effa had established a precedent that ultimately benefitted all of the Negro League teams (as so noted on her Cooperstown plaque). The Manleys sold the Eagles after the 1948 season, but Effa still had a connection to her star Monte Irvin: the terms of the sale provided that the Manleys and the new owners would share any money received if a major league team paid for one of the players. This was potentially a moot point when Branch Rickey signed Irvin with no intent to pay the Eagles. Effa fought back claiming that the Irvin had a contract and that she would contest the signing. Rickey backed off and Effa made a deal with Horace Stoneham of the Giants for $5,000. After paying lawyer fees and giving a share to the new owners, Effa got $1,250. She used the money to buy a mink stole. Some Major League Highlights of Former Eagles: Larry Doby broke the color line in the American League in July of 1947. The next year, he became the first black player to hit a home run in a World Series, helping the Indians win their second title (they have not won since). Newcombe was the NL Rookie of the Year in 1949 and was both the MVP and Cy Young winner in 1956. In 1951, Monte Irvin led the NL in RBI’s and was instrumental in the famed comeback by the Giants to catch the Dodgers to force a three-game playoff for the pennant. Irvin got a hit in each playoff game, including a homer to help win the first game. In Game 3, Newcombe started the game, but was relieved in the ninth by Ralph Branca who gave up the famous 3-run homer to Bobby Thomson. The Giants then met the Yankees in the World Series where Irvin became part of history by playing in the first all-black Series outfield alongside two fellow former Negro Leaguers (Willie Mays of the Birmingham Black Barons and Hank Johnson of the Kansas City Monarchs). Irvin ignited a Game 1 victory for the Giants by stealing home in the first inning on Yogi Berra. Irvin went on to hit .458 in the Series, but the Yankees won in six games. Irvin was on a Series winner in 1954 when the Giants beat the Indians. After the Eagles: After the Eagles were sold, Effa continued her work in community and civil rights organizations. But her true cause was keeping alive the history of the Negro Leagues and pushing for the induction of Negro League players into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. She finally saw some movement in the early 1970’s as Satchel Paige was inducted in 1971, followed by five other players through 1975. To emphasize that many more should be inducted, Effa self-published a book with sportswriter Leon Hardwick in 1976 titledNegro Baseball – Before Integration. Included are 73 biographies of players she felt should be considered for enshrinement. Progress remained slow with only three more players being added before the special committee to add Negro Leaguers was disbanded in 1977. The 80-year-old Effa Manley still had her voice, “Why in the hell did the Hall of Fame set that committee up, if they were going to do the lousy job they did?” She fired off letters to the Hall of Fame, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and C. C. Johnson Spink, publisher of The Sporting News: “I would settle for 30 players, but I could name 100.” Spink’s column of June 20, 1977, seemed receptive to this crusade by a “furious woman.” She liked that description and saved the clipping. In 1978, Effa was the special honoree at the Second Annual Negro Baseball League Reunion. Monte Irvin was there and saw Effa wearing her mink stole. He asked if it was the one she got from her sale of Irvin’s contract to the Giants. “Yes, it still looks good and keeps me warm.” It would take another quarter century, but some 35 Negro Leaguers now have plaques alongside Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and other greats in Cooperstown. Effa’s Newark Eagles are well represented. The team played from 1936 to 1948, just 13 years. But that was enough time for seven Hall of Famers to play a good part of their career in Newark. [To put this in perspective, the Royals have played 50 seasons and produced one Hall of Fame player, George Brett.] The Eagles of course have another representative in the Hall of Fame – the team’s top executive, Effa Manley. She was inducted in 2006. Effa’s Hall of Fame induction was a posthumous award. She died in 1981 at age 84. Inscribed on her gravestone: “She Loved Baseball.” Lonnie’s Jukebox: Three selections today. For those of a certain age (teenagers in the 50’s/60’s), you may remember that you paid a quarter for three plays on the jukebox. These are free. First, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. I urge everyone to attend and buy a membership. When you walk through the Field of Legends, you will see two of Effa’s players, Ray Dandridge at third base and Leon Day in right field. The player she could not sign, the elusive Satchel Paige, is on the mound. This clipshows NLBM President Bob Kendrick describing the “Beauty of the Game” exhibit (2:30). Second, the 1992 movie A League of Their Own. This is on my mind because director Penny Marshall died last month, and scenes from the movie have been popping up on social media. I have always been a fan of the movie. From Geena Davis to Tom Hanks to Madonna, the acting is superb, although I single out as my personal favorite Jon Lovitz as the hilarious baseball scout. Joe Posnanski did a column on his 10 favorite things about the movie, and one of his points reminded me of the subtle civil rights message. The real-life “league of their own” was segregated just like its male counterpart. In a mere 15 seconds, the movie tells a very big story of the times. A black woman has left her seat – from what is obviously the segregated seating area down the right field line – to retrieve and throw back an errant ball. She does so with obvious talent, and the message is that she is not racially eligible to play in the game. See the cliphere. In 2014, Penny Marshall announced that she planned to direct another baseball movie, this one about the life of Effa Manley. The screenplay is by writer Byron Motley, the son of Bob Motley, the Negro League umpire who this past year was honored with his own statue on the Field of Legends (behind the catcher at home plate in the NLBM photo above). I checked in with Byron, and he tells me that the project is still moving forward and to “stay tuned.” Byron’s tribute to Penny is here. And third, the classic protest song “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye. As the turbulent 1960’s were coming to an end, Gaye was reevaluating his concept of music. He was “very much affected by letters my brother was sending me from Vietnam, as well as the social situation here at home.” So Marvin was receptive when Renaldo “Obie” Benson of the Four Tops brought him an untitled song that he was working on after seeing war protestors beaten by the police. Benson did not classify his piece as a protest song, “No man, it’s a love song, about love and understanding. I’m not protesting, I want to know what is going on.” Gaye added some of his own lyrics and gave the song its title. He went to Barry Gordy at Motown, but Gordy said that it was really a protest song and would be bad for business. When Gaye persisted, Gordy relented because he did not want to offend his star. The single was released in 1971, and it turned out fine for business – the song went to #2 on the pop charts and topped the R&B charts for weeks. The song is a soulful anthem about war abroad and socio-economic problems at home. Some 48 years later, the lyrics of the song continue to resonate: We don’t need to escalate You see, war is not the answer For only love can conquer hate Don’t punish me with brutality C’mon talk to me So you can see me What’s going on Listen here. Attachments area Preview YouTube video Billie Holiday Strange Fruit 1939 Billie Holiday Strange Fruit 1939 Preview YouTube video Women of the Negro Leagues Women of the Negro Leagues Preview YouTube video A League Of Their Own Black Woman Scene A League Of Their Own Black Woman Scene Preview YouTube video Marvin Gaye - What's Going On Marvin Gaye - What's Going On When friends in Jerusalem and the Upper West Side send the same link, it makes sense to read it -- and pass it on. Roger Angell, 98, has some thoughts on election day and citizenship.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/get-up-and-go What could be more American than an essay on voting by a hallowed member of the writers' wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame? Enjoy....and vote. http://www.joedarrow.com/sports-figures/ (The art was a bonus. I found it on line, and consider my posting it here as an endorsement for any artist who can put these three dudes in the same work.) Stan Musial would know how Brandi Chastain feels. The great St. Louis Cardinal slugger went through his final decades honored by a huge statue outside the ball park, which, alas, did not at all capture his unique corkscrew, crouching batting style. Musial hated it, but being a get-along kind of guy, he smiled and said very little in public. The latest abomination is a plaque for Brandi Chastain, the great soccer player who converted the game-winning penalty kick in the final of the 1999 Women’s World Cup. Chastain’s team nickname was “Hollywood,” given by teammate and locker-room leader Julie Foudy. Asked to fill out a team questionnaire, Foudy came to the question: Favorite Actress? She wrote: “Brandi Chastain.” Brandi has panache. She showed it upon making the championship shot in 1999, and, just like Cristiano Ronaldo and all the guys, she ripped off her jersey – in the center of the Rose Bowl – revealing an industrial-strength sports bra and just a few more inches of herself, an athlete at the peak. Chastain was a terrific full-field player, a footballer, smart and competitive. She was recently voted into the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame and honored with a plaque depicting, well, somebody named Ellsworth or Percy who won a club championship in golf or tennis back in the 1920’s. “Brandi Chastain is one of the most beautiful athletes I’ve ever covered. How this became her plaque is a freaking embarrassment,” tweeted Ann Killion of the San Francisco Chronicle. The plaque will apparently be re-done. Chastain was gracious about it, as reported by Victor Mather in The New York Times. (Check out the links with other examples of wretched sports iconography.) Musial, who died in 2013, generally took the high road about the statue by Carl Mose. I wrote about it in my biography of Musial, and my late friend, Bryan Burwell, sports columnist of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, gave his art critique in 2010:

http://www.stltoday.com/sports/baseball/professional/musial-statue-must-go/article_72b0bf1e-952f-582c-b52b-0b8ffe984b0f.html Stan the Man did like a much smaller statue by Harry Weber, part of a series of St. Louis ball players outside the ball park, including Cool Papa Bell, immortal Negro League star. This one captures Musial’s energy in his follow-through. Even on a plaque, Brandi Chastain deserves to look like herself and not Mickey Rooney or Jimmy Carter. I’m not an artist, but how hard is that? NB: The Reply/Comments section seems to be out. I cannot add a comment from here. The company had this problem a month ago and took a week to fix -- or give out information. I don't have the patience to deal with their tech department right now. Anybody with my email who has a comment, please be in touch. GV (Thursday: I can put one foot after the other, partially because of thoughtful columns by Nicholas Kristof and Gail Collins, and also because of the poem from Altenir Silva, writer friend from Rio: “I want to dedicate this poem written by the Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade (October 31, 1902 – August 17, 1987). Here in Brazil, we always read it, when we are looking for better days. Best – Altenir.”) What Now, José? By Carlos Drummond de Andrade The party’s over, the lights are off, the crowd’s gone, the night’s gone cold, what now, José? what now, you? You without a name, who mocks the others, you who write poetry who love, protest? what now, José? You have no wife, you have no speech you have no affection, you can’t drink, you can’t smoke, you can’t even spit, the night’s gone cold, the day didn’t come, the tram didn’t come, laughter didn’t come utopia didn’t come and everything ended and everything fled and everything rotted what now, José? What now, José? Your sweet words, your instance of fever, your feasting and fasting, your library, your gold mine, your glass suit, your incoherence, your hate – what now? Key in hand you want to open the door, but no door exists; you want to die in the sea, but the sea has dried; you want to go to Minas but Minas is no longer there. José, what now? If you screamed, if you moaned, if you played a Viennese waltz, if you slept, if you tired, if you died… But you don’t die, you’re stubborn, José! Alone in the dark like a wild animal, without tradition, without a naked wall to lean against, without a black horse that flees galloping, you march, José! José, where to? * * * (Wednesday: All right, Joey Nichols is elected. I have nothing coherent to say as of Wednesday but may bounce back soon. Meantime, all comments, suggestions, verbal hugs, second-guesses or flat-out told-you-sos are welcome in Comments. I'm turning on classical music. GV.) Monday: I have never watched any reality show, intentionally, but one time I accidentally clicked on somebody named Simon, who was cruelly dissecting a guest. “What a horrible person,” I thought, pushing the clicker. “Who would let him into their house?” Of course, I never watched Trump on his show because almost everybody in New York knew him as a dolt and a poseur, a punch line. He was Joey Nichols to our collective Alvy Singer. Say it together: “What an asshole.” We knew. Now it turns out that a significant chunk of the country does not know, cannot process information about Trump’s business dealings, is not offended by his ugly boasting about sexual misconduct. The country, founded by patriots and enlightened leaders, has been dumbed down by the reality-show persona. At the same time, people stopped reading newspapers. They cannot tell the difference between news-gatherers and the comedians on the tube. Grown people repeat stuff that has been proven false. Go into a school sometime and talk about issues on the front page (or web site) of the Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian. Blank looks. Trump is putting journalists in pens and mocking them. As he rolled over the cardboard Maginot Line of Republican challengers, Trump unleashed a barrage of incomplete sentences, incomplete thoughts, utter untruths, in the sing-song voice of an undeveloped human being. In a sing-song voice. Trust me, I’m telling you, in a sing-song voice. I have developed earworm, the condition when some piece of music is repeated so often that it bores its way into the eardrum, and stays there, repeating itself. It keeps repeating itself, believe me, in a sing-song voice. Other people are reporting earworm from this endless election. In the last catatonic days, I have been flopping in front of the tube like a beached whale, hoping that Steve Kornacki and Joy Reid on MSNBC, or maybe John King on CNN, will point at the state that confirms it is almost over. I’ve heard this condition described as “a great national nightmare” or a “societal nervous breakdown.” On Sunday evening, I made a break for it. I went upstairs and put chamber music on the CD player and read a new book I discovered in the library: “The Face of Britain: A History of the Nation Through Its Portraits” by Simon Schama – great stuff about Winston Churchill and Henry VIII and John and Yoko and the artists who tried to represent them. For a few hours, the earworm went away.  Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Joseph Cornell was already well known for his collages in small boxes during the mid-50’s when I was in high school. Our busy road (188th St.) dead-ends into Utopia Parkway just south of Cornell’s home, maybe three miles from my childhood home, but I don’t remember my cultured friends and teachers ever mentioning him. The Jamaica High School paper interviewed famous New York people and probably could have gained an interview with this introverted soul but, like me, the editors had not discovered him. I am thinking about Cornell because my daughter Laura just took his biography – “Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell,” by Deborah Solomon -- out of the library. It’s been around since 1997 yet it took me this long to read about this artist who lived with his widowed mother and his younger brother who was limited by cerebral palsy. Cornell is stereotyped as the hermit who stayed home on Utopia Parkway, caring for his mother and brother, and when the world quieted down at night he would snip others’ work and blend them with memorabilia of France, or incongruous mundane objects to create new form. I once met Louise Nevelson at a party. She made us roar by describing how she bellied into a dumpster to retrieve some artifact she could use in her sculpture. Cornell was no less driven. Somehow, he managed to work at menial jobs in the city, to support his family, while haunting the art galleries and bookstores at lunch hour and then take the train back to Flushing. People called him a a recluse but really he was a Zelig of an Outer Borough who knew Dali and Duchamp and de Kooning. Tony Curtis came to his house in a limo! Cornell sought out ballerinas and actresses, shopgirls and students. Audrey Hepburn sent back one of his boxes. Susan Sontag enjoyed his company. His work celebrates sensuality, small hotels in Paris, birds, mystery, beautiful women. He died in 1972 at the age of 69. The author informs us that his short, intense crushes were "platonic." I liked Cornell even better when I read that he loved the haunting music of Erik Satie, who lived in a squalid little flat in the outback of Paris. Cornell's boxes and Satie's compositions are a perfect fit. I have loved Cornell's work since my wife, an artist, introduced me to museums and galleries. Maybe I am particularly affected because I grew up in Queens, in a narrow house much like Cornell's. Next door, a few feet away, two brothers, waiters named Rocco and Luigi, practiced the scales and the arias on summer afternoons with the windows open, before going to work. In Queens, we knew that “it” was just a subway ride away. And all that time, maybe three miles up the road, Joseph Cornell was caring for his family and making his boxes. This very young baseball season has been so much fun, just to have the sport back but obviously for the 10-3 record through Sunday.

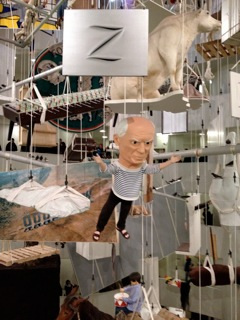

Then Jerry Blevins received a fractured arm and Travis d'Arnaud a fractured hand within minutes of each other as the Mets beat the Marlins. Since the first weird days of 1962, Mets fans have known that following this team demands great mood shifts. But this is ridiculous, after promising the Higher Power, just get me through this nuclear winter of Little Anthony and the No-Names and let me watch Juan Lagares chase fly balls. . Baseball is liberation from the yammering of cable news. . It’s sticking up for Bartolo Colon’s right to start opening day and watching him win his first three starts – and driving in runs in two consecutive games – and fielding his position, for goodness’ sakes. I went to opening day at New Shea, hordes of macho males (and females, too), whacked on alcohol or testosterone or who knows what, conducting the rites of spring that reminded me of Brueghel and Bosch, collaborating on their epic St. Patrick’s Day in the Lower Depths of Penn Station. Nobody watched the game. Back home, games are faster, so much faster so that you cannot click away and watch a snippet of a movie you never knew existed. Now, when you click back, there is already an out and a runner on first. Congratulations, baseball, for making those lugs stay in the batter’s box. The Mets and the Other Team in Town have opened with division rivals. This is a wonderful thing because the games have extra value for post-season possibilities, but more immediately because they bring home the familiar faces, the worthy oppositions. In the Madoff Era, the Mets have been the soft underbelly of the National League. Now they are going through the first two weeks – Bryce Harper and the Nationals, Andrelton Simmons and the Braves, Chase Utley and the Phillies, Giancarlo Stanton and the Marlins. But what is Ryan Howard doing lurking in the Phillies’ dugout? One thing I hate about contemporary big-biz baseball: the looming salary dump, further devaluing gallant players who got a bit old or a bit hurt. After two weeks, the timid, repressed optimist dares to whisper, “Wait…those teams aren’t that great right now.” Spring. Early spring. False spring. Who knows? Out-of-town box scores vanish from the printed page. You could spend an entire breakfast or commute checking the box scores. Now you have to read the front page. Yikes. But at least there is the two-week glory of watching Soft Hands Lucas Duda hitting to the left side, playing grounders like a big cat. Sandy Alderson was right. This guy is no oaf. Then again, how could the Mets send down Eric Campbell and open the season with a four-player bench? Campbell came back swinging hard -- and his throws from third base are special, too. Now the Mets have to replace two players who have been so vital in these early days. Meanwhile, on the team from another borough, Alex Rodriguez, the man we love to hate, is keeping the Anonymous Yankees almost respectable. Maybe he will shame the owners into paying him his bonus. Pay-Rod, the working man’s hero. Who woulda thought? Your thoughts? We recently visited friends for a lovely dinner and conversa-tion. The highlight just might have been seeing a new cycle of work by our hostess, Rosa Silverman. The nice thing about having a web site is being able to display art, just because. A giant foosball table for 11 players per side? Horses suspended in mid-air? Picasso in the sky with sandals? A giant tombstone cataloguing England’s soccer losses (no victories whatsoever)?

Maurizio Cattelan insists he is retiring, not that I believe him for a moment. But Sig. Cattelan certainly gives new meaning to the dreaded R-word. The Guggenheim Museum held a celebration of voluntary endings on Saturday night. The ramparts of the Frank Lloyd Wright building were jammed on the final weekend for the show – Sig. Cattelan’s letting it all hang out, so to speak. Just about his entire output of 51 years on this earth was suspended from the ceiling. I have seen many athletes take their leave of the arena, rarely on their own. When I was as young as the players, some of my friends on the Yankees would talk in hushed tones about a player who had been cut from the team. “Hey, did you hear about so-and-so? He died.” A bunch of people from various disciplines were asked by the Guggenheim to illustrate voluntary retirement. In men’s sports, retirement is often connected to that intimate item of sporting equipment known as the athletic supporter, or jock, which protects what any male athlete would say are his most treasured possessions. When a player retires, I reminded the audience, he is said to “hang up his jock.” Not being much of an athlete myself, I wanted to know if athletes actually “hang it up.” I contacted some of my athlete friends from my days at Hofstra College on Long Island. Stephen Dunn, who won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 2001, was a fine player on the basketball varsity that had a 23-1 record in 1959-60. Stephen was known as Radar for his long-range accuracy, and later played in a weekend professional league. When I asked Stephen about the end of his active basketball career, he wrote to me. (Yes, that Pulitzer-prize poet uses email.) “The jock strap, in this regard, has a kind of moral, uplifting quality to it,” Stephen wrote. “When I hung mine up it was a day of sadness, but only for me.” He added that only his wife noticed his “retirement” – and she did not think it was a big deal at all. Another friend from the old days, Lou DiBlasi, went on to be a high-school coach and has written a book about the legendary Tiny Twenty team of 1956. He also played on the undefeated Hofstra team in 1959. After their final victory, they held what he described as a “hang ‘em up ceremony,” which involved pounding some nails into a board, writing the names of the seniors, and hanging up their jocks, accompanied by, I am assuming, copious amounts of beer. The captain of that team was in the hospital for that final game, because of an appendectomy. They infiltrated the hospital with the beer and the board, and hung up his jock, too. At the Guggenheim, I gave what I hope was a brief talk on the history of retiring athletes’ numbers – Lou Gehrig’s No. 4 on July 4, 1939 (the day I was born; I remember the hubbub quite well.) The Yankees will soon run out of single-digit numbers after they retire Torre 6 and Jeter 2. Other speakers talked about forms of voluntary change – one man had given up the priesthood; a woman talked about contraception; a psychiatrist talked about endings in her field; a man did a spin on jarring black standup comedy that I loved; and somebody else talked about what I guess you could say is the ultimate form of voluntary retirement – suicide notes, themselves an art form. By contrast, “hanging it up” seems delightfully benign. We didn’t stay for the scheduled Courtney Love finale around midnight. As I left, I could see the young and the hip congregating underneath Maurizio Cattelan’s mock animal skeletons and newspaper headlines about the Brigati Rossi and busty nude sculptures. I’ll believe the retirement when I see it. Meantime: Bravissimo, Ingeniere. For some delightful reason, I have been asked to give a brief sporting flavor to the seven-hour retirement ceremony of sculptor Maurizio Cattelan at the Guggenheim Museum on Jan. 21. Cattelan is officially hanging ‘em up by suspending much of his artwork from the ceiling of the Guggenheim. That should be a trip.

As I imagined the farewell for a sculptor, I could not help but think about two sporting ceremonies I attended – both, bizarrely, on Sept. 28. The one on Sept. 28, 1947 was my first time in Yankee Stadium. I was 8, and it was the last game of the season, and the Yankees were honoring Babe Ruth, who was dying of throat cancer. (The Babe, in his outsize way, had three farewells – one that summer, the other next spring, before he died on Aug. 16, 1948. This was the middle one.) I can remember his camel hair coat and his damaged voice echoing around the Stadium’s rudimentary speaker system. The Stadium’s autumnal shadows enforced the gloomy tone, first set for Lou Gehrig in 1939, of dozens, nay, hundreds, of Yankee ceremonies, many of them honoring pinstriped heroes who often seem to die young. Those spectral sounds still seem to echo in the newest version of the Stadium – even though it’s across the street. A more upbeat ceremony took place on Sept. 28, 1982, at the farewell game for Carlos Alberto, a stylish defender from Brazil, who had finished his career with the Cosmos. They brought up his old team, Flamengo from Rio, in its red and black uniforms, and he played a half for each team, the way soccer farewells are done. I was new to the sport in 1982, but could not miss the love and respect the players had for Carlos Alberto, and for the game itself. As Carlos Alberto took a long tour around Giants Stadium, waving and shaking hands with the fans, the new-age speakers played Carly Simon’s “Nobody Does It Better.” Every time I hear that song, I think of smooth old Carlos Alberto. Now, the rankest outsider in that world, I will witness the addio to Maurizio Cattelan. With his diverse works dangling from the beams, the farewell at the Guggenheim is not likely to be anything like the one for the Babe or Carlos Alberto. I’ll furnish a report. |

Categories

All

|