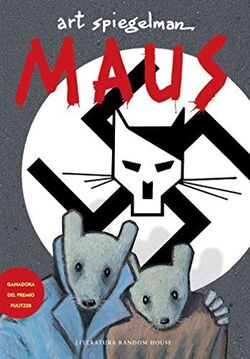

How strange, to be reading a book about the Holocaust while another slaughter takes place. For no good reason, I missed reading Art Spiegelman’s classic book, “Maus,” a graphic novel about his parents’ survival, of sorts, from Auschwitz. I always meant to read it since the first part was published in 1986, but just did not until now. However, when school boards and mayors and other American worthies began to ban this Pulitzer-Prize winning book as too controversial for young people, I realized I had to join the millions who had read it. I tried to take it out from the wonderful Nassau County library system only to discover I was 31st in the electronic waiting line – but fortunately there was a Spanish-language copy available from a few towns away. With my moderate Spanish and a handy dictionary – and the graphic panels displaying cruelty and hope – I read it. Meanwhile, a latter-day Hitler has decided to take over a neighboring people, even if he has to kill thousands, maybe millions, of them – “Man’s inhumanity to man,” to quote the Robert Burns poem, all over again, "a boot stamping on a human face – forever," in the words of George Orwell. Art Spiegelman was documenting it decades ago, as his aging father began to tell how the world fell apart in the late 30s in Poland, when the Nazis were flexing their muscles and most locals were none too hesitant to cooperate. Chapter by chapter, Spiegelman portrays himself, already an adult cartoonist with a political bent, getting his widower father to tell the story of his courtship and marriage and the inexorable plodding toward Auschwitz, followed by a reunion of the parents and the path to Rego Park, Queens, and the Catskills in the summer – heaven on earth, sort of, for people who have lived in Nazi hell. The artist portrays Germans as cats, Poles as pigs, Americans as dogs, the British as fish, the French as frogs, and the Swedish as deer. What would the Russians be, if and when we get to a similar re-telling of this horror? Perhaps, lumbering, dim-witted bear cubs, with an old and rabid bear sending them off to mutual slaughter, up against a Ukrainian people with a (Jewish!) hero/president, trying to rally the world. As the father talks to his son, he tells how he and his wife went underground, surviving with the help of the occasional kindly Pole, and then how they survived in adjacent camps, he by being fluent in English and German as well as Polish – and learning skills that make him valuable to the warden, who feeds him, protects him. The father tells of death, step by step, of men around him. It’s a horror show, but also a testimony to the will to live – now being seen by Ukrainians who fight bravely for what is theirs, while many elderly and children are sent to relative safety. Spiegelman’s masterpiece is worth finding – buying -- and assimilating. In “Maus,” people are flawed, one way or the other, but the urge to survive against the wicked is strong. For the people of Ukraine, my heart goes out. Bob Mindelzun was a great soccer teammate. He knew the sport, had played it in Poland, and was big enough and fast enough to be one of the best players on our team. He laughed easily and was good company on the buses and subways that took us to road games in Queens and Brooklyn. He spoke English with a thick accent, which was not unusual in Jamaica High School in central Queens. I remember teammates from Italy, France, Sweden, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, and I think Greece. Our great captain, Bob Seel, had learned his soccer in the German-American clubs of Ridgewood. We did not talk about backgrounds, not in the mid ‘50s, when the world was still processing what exactly had happened in the ‘30s and ‘40s. The wounds were so recent that words like “Shoah” and “Holocaust” were not part of our vocabulary, not yet. After graduation, I kept in touch with many accomplished and interesting friends from Jamaica; five of my teammates became doctors, including Dr. Robert Mindelzun, radiologist and professor at Stanford University. I have not seen him since graduation, but lately I realized that Bob came from Eastern Europe. Recently, we talked on the phone, and I asked a few questions, and he said, “Would you like to see my book?” Yes, I said. Please. Bob wrote and published, in 2012, a book entitled “The Marrow of Memory,” about the terrible journey of his father and mother and their only child, from bombed-out Warsaw, thousands of miles further north into Russia, first to the Komi region, with its Finno-Ugric tribal history, near the Arctic Circle, to camps for refugees, the most endangered of whom were Jews, like the Mindelzuns. In this time of pandemic….and a rampaging American president…it is easy to blurt that life has never been this dangerous. Bob’s book tells of other times.  Book by my high-school soccer teammate, cover by his mother, Halina Mindelzun. 2012. Available, according to Amazon. Book by my high-school soccer teammate, cover by his mother, Halina Mindelzun. 2012. Available, according to Amazon. This little cluster of family, which had lived a comfortable urban life in cultured Warsaw, now had to survive. The Jewish Poles were particularly vulnerable, including the little boy. “They just had to see you with your pants down and you were done,” Bob said recently, a referral to the Jewish practice of circumcision. Leon and Halina and young Robert stayed together as long as they could in hideous conditions – minimal food, terrible sanitary and medical conditions. Early in the war, his father re-enlisted in the Polish army – as a truck driver, for the relative safety, and for many months he was away, on duty. “We did not know if he was dead or alive,” Bob said recently. There was always danger. Bob’s mother loved to dance, and once went to a social evening in a camp, where she was asked to dance by a Russian officer, as acrobatic as a professional folk dancer. At the end of the traditional kazotsky, he landed gracefully at her feet, and kissed her shoes. She understood the danger, and never went back to the social evenings. I was surprised by the number of photographs in the book – not just old family photos from vibrant Warsaw but also documents and photos from the war. Bob explained: The strength of rural life was the small villages, where even in wartime there were still amenities like photo shops, if you can imagine. Somehow, through all the upheavals, they kept a trove of photos and documents, many in this book. There was another advantage to living in the Arctic Circle: according to Dr. Mindelzun: up north there was much less disease than in the more southern regions. At the end of the war, the family was reunited in Warsaw, now bombed out by the Nazis, and came to realize many in their family had died or been killed. Others were in hiding, depending on good luck, the kindness of strangers. When the Cold War began to loom, the parents made the decision to emigrate to France – a tiny rented room in Belleville, a Paris suburb. They did not speak any French. The father, seeking a new trade, traveled all over Paris by Métro, the subway, only to be confused that so many stations had the same name: Sortie. The mother explained that was the word for Exit; it became a family joke among the three of them. For a time, the parents had to put their only child in an orphanage, but when they felt the menace of the Russians in the Cold War, they applied to several nations and were accepted by the United States. They arrived in Queens in 1953, still together. And that’s where the book ends. Bob alludes briefly to his father opening a modest luncheonette in Jamaica but he does not write about Jamaica High, with its great tradition of education. (The geniuses who run the city recently terminated Jamaica High but the beautiful building on the glacial hill, built to last forever, houses smaller schools.) He does not tell how he played soccer at Queens College and eventually took his parents with him when he began his medical career in the Bay Area. The father lived to 89, the mother to 93, and they told him stories of that awful time. He used great swatches of their tales in his book. Our friendly and skillful teammate joking in the fourth or fifth language of his young life, later married Naomi, an artist in the Bay Area, whose shimmering versions of his way stations grace the book. They have raised two children, one of them a doctor and writer. I asked my teammate to compare the time of his childhood to the dangers, medical and political, of today, and he said: “As unpleasant as this is, it doesn’t compare.” He has seen worse. This book is a memorial to all who perished, and those lucky enough to survive. Speaking of survivor-athletes, my friend Leo Ullman and his parents survived in wartime Netherlands, and he is the subject of a prize-winning documentary, “There Were Good People Doing Extraordinary Deeds…Leo Ullman’s Story:"

https://youtu.be/D6ic9DUJWws (Leo also has a huge collection of Nolan Ryan memorabilia, now the subject of a webinar:) https://stockton.zoom.us/rec/share/8EVPg60t84hxAdzwZty2unHcITV1jlBJTtfC5lPKm_SU9yj2EYl2Xw3-qUgPfzo.znc6g48IFlSD92Lj Not bad for a child who was sheltered in the Dutch countryside while his parents hid in an Ann-Frank type garret in Amsterdam -- and with the good will of this country back then, they made a success here, like my teammate and his family have done. (I am thinking of leaving this World Cup match post up for a while. Please feel free to chime in, whenever. The NYT is doing a great job from Russia. And my former Times soccer pal, Jeffrey Marcus, now free-lancing, has his own learned World Cup newsletter. To sign up: http://jointhebanter.com/about/) June 14. Russia 5, Saudi Arabia 0. Knowing nothing about either team, I put on Fox five minutes before kickoff. I noticed that Russia had a defender named Fernandes (from Sao Caetano del Sur, Brazil) and a defender named Ignashevich whose face looks like hardened cement and who does not sing the beautiful Russian anthem. (Turned out, he’s 38, hasn’t played for the national team since 2011, so he may be out of practice for singing the anthem. Or his lips don’t move.) Then I noticed a lanky midfielder named Golovin, with a Lyle Lovett hairdo, who reminded me of one of the most charismatic and talented leaders I have ever met, Mrs. Gollobin, the director of the Jamaica High School choir and chorus back in the day. She once snapped at me, “George, be a mensch,” and I straightened right up, in her presence, anyway. I decided to root for Aleksandr Golovin. Good choice. He set up the first three Russian goals for adept passes through the gaping Saudi players. I looked him up – 22, and being scouted by Juventus. He showed his youth by picking up a pointless yellow card in the final minutes. By the time he curled a free kick into the corner in the closing seconds for the fifth goal, Golovin had surely confirmed his ticket to Torino. Mrs. Gollobin would be proud of him. Having covered eight World Cups for the NYT way back when, and having written a book about them, (https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2014/0530/Eight-World-Cups-by-George-Vecsey-decodes-international-soccer-for-newbies,) I tried to compare this day (on the tube) with openers I attended: The fans were a classic World Cup mix; could have been anywhere -- international types who could afford a ticket. Pretty woman in a red and white folk dress; guys with goofy headgear. One other observation: how nice it is to hear old World Cup hands, J.P. Dellacamera and Tony Meola, working for Fox, and confirming that one does not need a British accent to call a match for U.S. television. How was your first match? What a perfect sign of spring -- survival and hope.

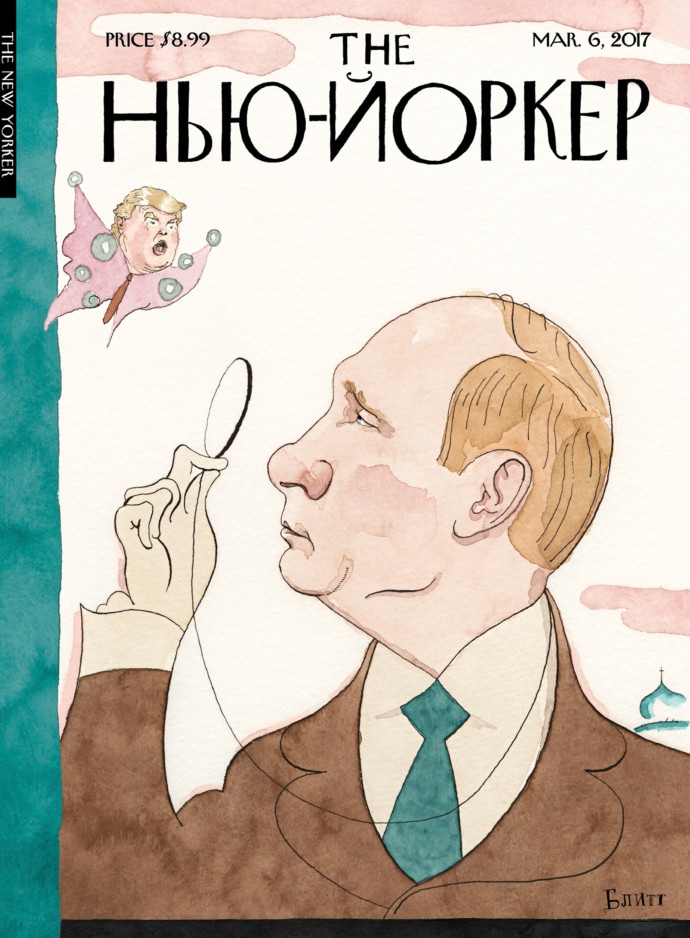

Man, do we need that. I’ve been moping with a head cold, or maybe it’s from the front pages, but along with Passover and Easter come the openings for the Mets and Yankees, and not a moment too soon. Soccer-buff Andy Tansey took this photo at the Mets/Willets Point IRT station. I remember the first day at funky little Jarry Park in Montreal in 1969. First game ever in Canada. I got there early and workmen were still touching up the premises. * * * Who doesn't love Opening Day? Lonnie Shalton, baseball buff in Kansas City, wrote his own appraisal of the big day. (He mentions a few things I typed -- and also lots of other baseball insights.) http://lonniesjukebox.com/hot-stove-71/ * * * Fresh paint may cover some of the flaws of the Mets. They have Syndergaard and DeGrom going in the first two games, and we’ll take our chances after that. The Mets don’t seem any better than last year – scary thought, that – but the owners did bring back old-reliable Jay Bruce, and maybe Conforto will be ready in late April, and maybe Céspedes can make it through a week or a month. At least the Mets are haimish – with familiar faces like Weeping Wilmer and Old Pro Cabrera and Prodigal Son Reyes. They are ours, for better or worse, or for right now. Having seen the first home game in 1962 in the Polo Grounds, I know that to be a Met fan is to root for the familiar, with all its goods and bads. The Yankees open in Toronto. Why is this Yankee team different from all other Yankee teams? Because they have a new look with Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton, both powerful, both charismatic. I’ve been conditioned by the recent dynasty to respect and enjoy the Yankees, as much against my religion as that is. Judge is so mature and Stanton is so poised. Plus, I read that good old John Sterling is working on his home-run call for Stanton – and that John had his cataracts removed and doesn’t have to fake his long-ball calls so blatantly. (What took you so long, dude?) This is all avoidance, of course. The world is screwed up. Russia incinerated some of its young people in a mall fire through incompetence the way our lawmakers and their NRA patrons put our young people in shooting galleries passing as classrooms. Did you see the faces of young Russians protesting the shoddy construction and careless operation that killed their contemporaries? This masterful photo by Mladen Antonov of Agence France-Presse mirrors the mournful but determined never-again postures of American youth last week. The world is indeed small. I can read a bit of Cyrillic – the young person with the long hair and olive jacket has a sign that says коррупция – Corruption. Can they haunt Putin the way protestors from Parkland are haunting Rubio and all the other “public servants” on Wayne LaPierre’s handout list? In the meantime, may the paint dry in Queens by Thursday morning. The New Yorker has long been a literary icon but through the odd couple of David Remnick and Donald Trump it has even ratcheted up its importance as a worldwide asset.

Hardly an issue arrives without at least one article about the tentacles of money and power between the United States and Russia and beyond. In the March 6 issue is “Active Measures,” by Evan Osnos, Remnick and Joshua Yaffa, exploring just what Vladimir Putin is up to. At the core is Remnick’s own expertise from his long posting in Moscow. (He started as a young sportswriter, great company at the Olympics.) The March 6 cover is the annual homage to the New Yorker’s dandified mascot, Eustace Tilley, monocle and all, inspecting a yappy butterfly with orange hair. Putin’s normal expressionless face seems to show a trace of amusement: “Who is this strange little fellow?” The March 13 issue has an article by Adam Davidson entitled, “Donald Trump’s Worst Deal,” which could be almost anywhere. In this case it is about Trump sending his entrepreneurial daughter Ivanka-the-Brand to supervise a “luxury” (well, what isn’t?) hotel going up in a grubby corner of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. This Trumpian deal staggers like Trump’s desperate lunges for success in Russia but in this case some investors are from Iran. The Trump involvement is said to have been terminated in December -- after American voters chose this great American businessman as their president: its obligations and secrets glow like Chernobyl. Literature has not been ignored by the New Yorker. In the past two weeks there have been two magnificent pieces: In the March 6 issue is a short story by Zadie Smith (“Crazy They Call Me,” from the song) imagining the inner voice of Billie Holiday in her final days: every word, every detail, is exquisitely placed, phrase by phrase, leading to the final cry from the soul the reader knew was coming. In the March 13 issue is a poem by Robert Pinsky titled “Branca” -- an ode to the pitcher Ralph Branca who passed recently at 85. Mixing his pitches, the poet refers to Branca’s Calabrian name, his huge family of origin, his instant friendship with Jackie Robinson, and his victimization by enemy spying in the signature moment of his long and admirable life. The New Yorker is best held in the hand, read at leisure as a ritual, early in the work week. In this age, great journalism is being done by the Times and Washington Post on the split second, on the web, and the New Yorker has kept pace. As of Thursday morning I recommend the great Jelani Cobb’s dissection of the latest blathering by Dr. Ben Carson, who equated slavery with immigration. (I have often thought that Carson’s problems with language and reality stem from an infusion of too much anesthesia during the pediatric brain surgery he apparently performed for decades, masterfully. Or, is he doing a Pee-wee Herman imitation?) Cobb, as one would expect, goes beyond my flippancy. The New Yorker also features Roger Angell on the traditions of the magazine, and also occasional pieces on, thank goodness, baseball. * * * I hope these links can be accessed; a subscription to the New Yorker includes full access to the web site. Remnick et al: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/06/trump-putin-and-the-new-cold-war Davidson: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/13/donald-trumps-worst-deal Smith: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/06/crazy-they-call-me Pinsky: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/13/branca Cobb: http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ben-carson-donald-trump-and-the-misuse-of-american-history?intcid=mod-latest Angell: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/looking-at-the-field The two Korean athletes’ selfie in the Olympic Village – now flashed around the world -- reminds me of another Korean gesture for common humanity.

It happened at the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul -- the first nearly complete set of Games after the American boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the inevitable Soviet payback at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. After the futile boycotts – making athletes pay for the failures of nations -- the two behemoths were back in the Olympic business in 1988. Just before the games began, I was at a reception at the media center. Koreans are more than generous in plying visitors with food, drink, gifts – and fellowship. (“They remind me of my relatives in Brooklyn,” a news-reporter friend of mine said. “They get up close to you, and they laugh and cry.” He loved them for it.) At this reception, a South Korean host mingled among the visiting journalists and spotted an American (me) and a Russian, both alone, both within arm’s length. He hooked one arm around me and his other arm around the Russian. "We should all be friends,” he urged us. “Come on, shake hands.” The Russian was as bemused as I was. I had no issue with Russians – had been in Moscow in 1986 for the Goodwill Games, midsummer, warm hearts, leaving me with a permanent affection for the people. But, geez, two journalists at a reception? Two strangers? A handshake? Really? The guy looked at me, and I looked at him, and he gave a very Russian shrug, and I did my best to imitate, as if to say, “что вы говорите” – whatever you say. We shook hands, I think the Korean took a photo, and we retreated to separate corners of the hospitality tent. Enough freaking brotherhood for one evening. Now I wish I had the photo, but that was before the age of digital. Nowadays, a North Korean and South Korean athlete meet in the village and take a selfie. Somebody else takes a photo of them. It goes around the world. We all take heart in this. Now we learn the North Korean athlete’s story is a bit more complicated. The latest article includes the phrase “coal mine.” But bless the people who care. Two of the most touching columns I have read about these Games were written by Roger Cohen and Frank Bruni in the Times. Cohen described the spiritual journey of an Egyptian volleyball player who wore a hijab in competition. (I don’t know anybody who writes better about Islam in the modern world than Cohen.) Bruni wrote about the high points of competition that made him cry. (I’m going to sound like a jerk, but my memories of Michael Phelps and swimming events at previous Olympics bring back a strong whiff of chlorine, not much else.) I do remember grand moments, many outside the arena -- like a warm-hearted Korean urging me to put down my little dish of kimchi and shake hands with a Russian. Watching the current Inoculation Frolics, I was reminded of my recent reading of the superb biography, “Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman,” by Robert K., Massie.

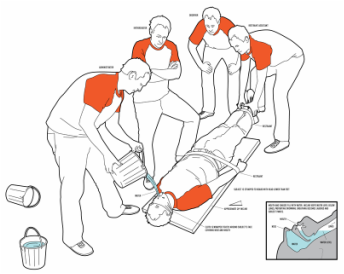

In the spring of 1767, smallpox was rampaging through Russia. Catherine II, the German-born, French-speaking empress of Russia, saw a beautiful young countess die in mid-May. After that, Catherine took her young son and heir, Paul, into the countryside, avoiding all public gatherings. Catherine was well aware that smallpox vaccination was being done in western Europe and the British colonies. (Thomas Jefferson, 23, the squire of Monticello, had himself inoculated in 1767.) She sent for Dr. Thomas Dimsdale, 56, of Edinburgh, who arrived in August of 1768 and cautiously tried to inoculate other women before the empress, just to prove his process worked. (Massie notes that Dimsdale proclaimed Catherine, 39, “of all that I ever saw of her sex, the most engaging.”) However, Catherine bravely insisted she go first and he took a sample of smallpox from a peasant boy, Alexander Markov, and inoculated the empress on Oct. 12, 1768. She developed the anticipated modest amount of pustules and illness but was back in public by Nov. 1. The doctor inoculated 140 people in St. Petersburg and another 50 in Moscow, including Catherine’s son and grandson. Before Dimsdale returned to Scotland, she rewarded him with 10,000 pounds and a lifetime annuity. By 1800, over 2 million Russians had been inoculated. The final word belongs to Voltaire, as it often does. The French philosopher was a regular correspondent with Catherine, although they never met. Massie writes: “Catherine’s willingness to be inoculated attracted favorable notice in western Europe. Voltaire compared what she had allowed Dimsdale to do with the ridiculous views and practices of ‘our most argumentative charlatans in our medical schools.’” Fortunately, in these enlightened times, we do not have any “argumentative charlatans.” Totally by coincidence, I am reading the wonderful biography by Robert K. Massie, “Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman,” and happened upon her very strong opinion of torture.

Catherine was one of the most intelligent monarchs in history – a minor Prussian princess imported to Russia as a wife for the insipid heir. She read and spoke French fluently and educated herself from lovers and advisors; she communicated with Voltaire and Diderot and other philosophes. And she soon took over the crown from her dangerously helpless husband, Peter III, who quickly died at some remove from her. In 1765, as empress, Catherine wrote series of “guiding principles” (Massie’s words), a Nakaz, which suggested changes in Russian laws. Even an empress had to run them past ministers and parliament, and she saw her thoughts whittled down considerably, but on July 30, 1767, she issued: “Instruction of Her Imperial Majesty Catherine the Second for the Commission Charges with Preparing a Project of a New Code of Laws.” One of the strongest passages was about torture. Massie, writing about the 18th Century, makes no link to the 21st Century, but he does note her words: What right can give anyone authority to inflict torture upon a citizen when it is still unknown whether he is innocent or guilty? By law, every person is innocent until his crime is proved…The accused party on the rack, while in the agonies of torture, is not master enough of himself to be able to declare the truth…The sensation of pain may rise to such a height, that it will leave him no longer the liberty of producing any proper act of will except what at that very instant he believes may release him from that pain. In such an extremity, even an innocent person will cry out, “Guilty!” provided they cease to torture him…Then the judges will be uncertain whether they have an innocent or guilty person before them. The rack, therefore, is a sure method of condemning an innocent person whose constitution is weak, and of acquitting the guilty who depends upon his bodily strength. Massie adds: “Catherine also condemned torture on purely humanitarian grounds: ‘All punishments by which the human body might be maimed are barbarism,’ she wrote.” I note from the Internet that several people have noted the link between her Nakaz and current events. (Catherine also condemned many facets of serfdom, or slavery.) She continued to rule with dependence on force and undoubtedly things went on (like the mysterious death of her husband) that were not unlike what took place in the dungeons of the KGB – or the interrogation pits of the American government. Nearly 250 years later. Catherine’s common sense and ideals still ring true When the photos started arriving from Crimea and eastern Ukraine, I had a flashback.

I’ve seen those guys, the ones in the leather jackets who emerge from the crowd, filled with venomous purpose. A few days later it hit me. Moscow in 1986. Church. We were there for the Goodwill Games, the Ted Turner sports jamboree, one of the great events I have ever covered. Crazy Ted, wandering around Moscow, the holy fool, screaming about saving the elephants. The city, warm and gentle in high summer, hospitable if threadbare in the time of glasnost. Older Russians getting tears in their eyes when they talked about the suffering in World War Two. My wife and I decided to go to church one Sunday morning, found a neighborhood Orthodox church, still open under the terms of Communism. There was incense, singing, a ritual up front, while in the back, older worshippers, mostly women, moved from corner to corner, bowing their gray heads reverently, kissing icons of their beloved saints. We were taken back to another time. The mood matched the feeling we received out in the street. While I worked at sports events, my wife took municipal buses to lavish circuses in distant neighborhoods. Old ladies appointed each other to watch out for her, made sure she got off at the right stop. We had also seen the old ladies brandishing umbrellas at traffic police who displeased them. This was their city, their world, still. Now, in church, in the heady cloud of incense, they prayed and kissed the icons. Then, a few young men materialized, wearing dark leather jackets in summer heat. Three or four of them meandered through the maze of icons and paintings, but not reverently, not at all. They stared at the worshippers, moving among them, nothing physical, but most intimidating. People ignored the thugs. I felt, well, I am an American, they might not want to menace me. In my pocket was a press badge that said: Игры доброй воли. I can still read it in Cyrillic and pronounce it. Goodwill Games. My wife and I stayed close to the thugs, spoke to each other in English. I have no idea if we affected them in the slightest. There was no recognition. They sauntered through the church, and left by a side door. I had not thought of them in decades. (I think more about Chernobyl, which had taken place a few weeks earlier, and still casts its poisonous shadow on the world.) But when the photos emerged from Crimea and eastern Ukraine recently, I felt a twinge in the pit of my memory. Putin kisses icons now. It’s a different time. Thugs still emerge from the shadows, thrusting their shoulders and elbows around. Really? It’s that easy? Wave a red card and people go away?

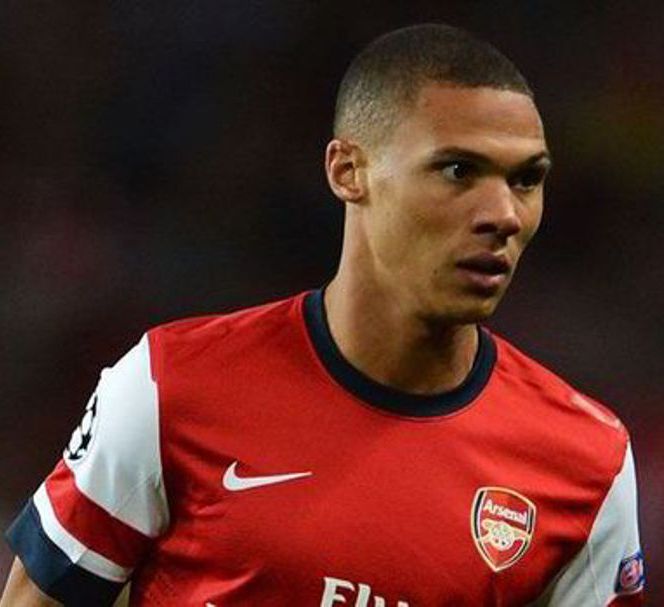

I’ve been obsessing about red cards since the United States and Russia began issuing sanctions in the past week. John Boehner can’t go to Russia? Does that apply in Congress, too? On Saturday, there was Roman Abramovich and his girl friend free to watch his club, Chelsea, rampage through Arsenal. But what if the West and Russia were to ratchet up the red cards, and the oligarchs and their money were not allowed into the West? What if the Nets’ owner, Mikhail Prokhorov, were not allowed to inspect Paul Pierce and Kevin Garnett, rusting away before his eyes? What about the billionaire who bought an $88-million pied-a-terre for his daughter on Central Park West? What’s the point of being an oligarch if you can’t go west for R&R? Why amass all that money in the first place? Speaking of sanctions, it’s time for soccer to wave the red card at referee Andre Marriner after his blatant mistake – and refusal to listen to reason – on Saturday. Chelsea was already leading, 2-0, in the early minutes. I thought Chelsea had a huge advantage, shooting from sunlight into shadow (sunlight! in London! in March!) but maybe it did not matter. Marriner correctly saw an Arsenal defender deflect a shot that was probably veering wide. Tweet! The ref promptly called a penalty kick for Chelsea and an automatic red card for Arsenal. Only trouble was, the ref waved the red card at No. 28 Kieran Gibbs rather than No. 15 Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain and his guilty fingertips, who had been closer to the goal. Anybody can make a mistake. But when the Arsenal players tried to explain, Marriner was too blockheaded to listen. His two assistants on the sideline were apparently daydreaming, so Gibbs went off. The authorities will switch the one-match suspension on Monday, but Marriner also needs time away, to learn how to reason. The match ended, 6-0, in favor of Chelsea, with José Mourinho demonstrating his seething super ego, the coldest stare this side of Putin. * * * Two other soccer observations: *-I’ve never been a fan of John Terry or Wayne Rooney, but both demonstrated their resourcefulness and skill in Champions League matches in recent days. *-I take back most things I ever said about the Dolans. James L. Dolan relinquished his wretched control of the Knicks this past week, and now Cablevision, owned by the Dolans, has added the Qatari station, beIN, to my cable package, just in time for the Clásico (Real-Barça, but you know that) on Sunday. Cablevision, le saludo. (And I forgot to thank fellow Queens-person Andy Tansey for calling my attention to the news about Cablevision.) People are comparing Vladimir Putin to the Russian tsar Peter the Great.

By some weird coincidence, I recently read “Peter the Great: His Life and World,” which earned Robert K. Massie the Pulitzer Prize in 1981. It is one of the greatest biographies I have ever read. Putin’s concern with expanding toward salt water may sound like Peter, but Putin does not demonstrate the curiosity and complexity of the tsar (1672-1725.) As tsar, Peter lived in the Netherlands for several years, learning how to build ships with his own hands. He encouraged European ways, first in Moscow, later in St. Petersburg. He also invaded, killed, tortured – all of that, too. In the current turmoil in Ukraine, the real comparison is between women. The other day at the naval base in Crimea, the wives of Ukrainian naval men stood watch outside the garrison. If Russian soldiers came any closer, they would have to face the women first. The stirring eyewitness report was in the Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/05/world/europe/no-bloodshed-in-a-standoff-at-an-airfield-in-ukraine.html The women had a spiritual ancestor in Catherine, the second wife of Peter the Great, who also faced potential disaster. Their union was one of the better love stories in history – a teen-age immigrant who impressed a tsar, became his wife, calmed him during his seizures, advised him, even cautioned him. And once accompanied him toward battle. In July of 1711, Peter got himself surrounded by Ottoman forces on a foray to the Pruth River, which flows from Ukraine toward the Danube. “In the center of the camp, a shallow pit had been dug to protect Catherine and her women,” Massie writes. “Surrounded by wagons and shielded from the sun by an awning, it was a frail barrier against Turkish cannonballs. Inside, Catherine waited calmly, whilke around her the other women wept.” For some reason, the Ottoman leader allowed Peter and his army to escape, in exchange for land that will sound familiar today. Peter lived to strengthen his empire, and the next year he re-married Catherine in a more formal ceremony. “Two years later, Peter further honored Catherine by creating a new decoration, the Order of St. Catherine, her patron saint, which consisted of a cross hanging on a white ribbon, inscribed with the motto, ‘Out of Love and Fidelity to My Country.’” Massie adds: “The new order, Peter declared, commemorated his wife’s role in the Pruth campaign, where she had behaved ‘not as a woman but as a man.’” The brave women outside the garrison in Crimea deserve a medal, also. |

Categories

All

|