|

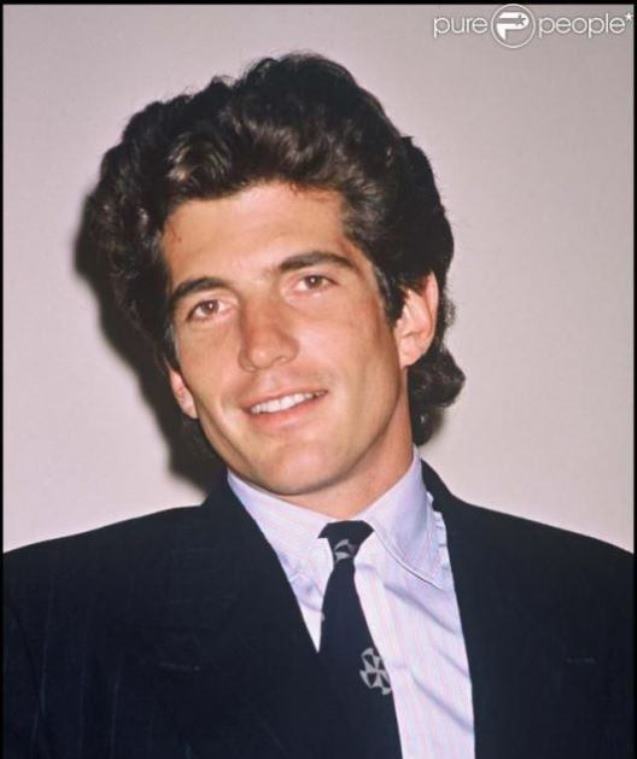

The classical music station was playing “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” by Ravel. It was beautiful, and I didn't know it, and I wondered why WQXR-FM was playing it on the second day of September while I was driving home from the US Open. Then I remembered: the Open of 1997, and another princess who died on Aug. 31, and how I saw her once at Wimbledon. Journalists see public figures, even on the sports beat: Jimmy Carter under the stands at Turner Field. Lyndon Baines Johnson on opening day in Washington, D.C. Hillary Clinton visiting the press box in Wrigley Field. And John F. Kennedy, Jr., right in front of me in Madison Square Garden. Coolest guy in the world. And Princess Diana at Wimbledon. I’ll never forget the eyes. The old press tribune was directly alongside the Royal Box. Princess Diana was on the guest list one day in the late ‘80s. We all checked her out early, and went back to our business. Later, I turned my head and caught those piercing eyes, looking back at us. Perhaps she wondered who that raffish lot was, as we chattered and gestured our way through the afternoon – a fitting Shakespearean upstairs/downstairs balance to the swells in the Royal Box. She should have heard some of the Brits with lurid commentary, imitating plummy royal accents. I’d like to think she would have laughed. Her two little boys were scuttling around the box, watched by helpers. Their mom was checking things out, with the curiosity we read about, her concern for the underclass, that is to say, us. I don’t know that she cared much about the tennis. She certainly seemed to be a seeker. * * * One evening in the mid ‘90’s, John F. Kennedy, Jr., was sitting in front of me at the Garden, a couple of rows up, behind where Spike Lee sits, facing the Knicks bench. He arrived late, wearing a nice suit, probably just came from work. He was by himself, and he appeared to be starving, keeping one eye on the game as he devoured a hot dog. Then he went to work on a large sack of fries. Just to Kennedy’s left, a boy around ten years old was staring at him. Either the boy knew who was sitting next to him, or he was salivating from the proximity of the fries. Kennedy popped in a few more fries. Did not turn his head. Did not smile or try to ingratiate himself with the boy. But like a point guard making a blind pass, Kennedy held out the bag of fries and shook it. The boy knew a good thing, took a handful. I don’t think he said a word but then again, JFK, Jr., was not looking for thanks. That was not necessary between a couple of guys who understood each other perfectly. The pass. The dunk. Kennedy understood hunger; the boy understood generosity. * * * After hearing Ravel’s “Pavane” on the car radio, I came home and googled up the music, written in tribute to a patron from the Singer sewing machine family, Winnaretta Singer, who was in a lavender marriage with the Prince de Polignac. Our age has few princesses, few princes, worth noting. I remember Diana’s piercing eyes, and how JFK, Jr., could see out of the corner of his eye. (Thirty years ago I wrote this sports column in The New York Times.)

November 21, 1983. Monday The Game Stopped George Vecsey We were playing touch football when the President was shot. The fiancee of one of the players came running through the park, calling: ''The President's been shot in Dallas. They've closed the Stock Exchange.'' We knew enough to pick up our extra sweatshirts that had served as yard markers and quietly to go our separate ways to whatever security our homes would offer us. The news on our car radios told us what we did not want to hear. We were mostly in our 20's, a collection of young journalists and baseball players whose vagabond hours allowd us to play touch football at midday all through the fall. We had short haircuts and nicknames like Killer, Joe D, Big Ben, Rapid Robert, Jake, Little Alvin and Richie Swordfish. As I look at our old photographs, I am struck by the optimism in our faces. It seemed like a very good time to be in our 20's, and starting our adult lives. I think John F. Kennedy had something to do with that. Since the day we picked up our sweatshirts and trudged off the field, I have often thought of the double irony of playing touch football in Kennedy Park, named after early settlers of Hempstead, L.I., not for those Kennedys. Today the name Kennedy is on New York's major airport and public schools all over the country. Eight days ago in Frankfurt, my wife told me that the broad boulevard on which we were driving was named Kennedystrasse. Just playing touch football at the moment the shots rang out was irony enough. Looking at the old publicity pictures of him now, in the 20th-anniversary glut of memories, I am struck by how awkward and poorly conditioned John F. Kennedy looks holding a football. Of course, for years there have been suggestions that he suffered from Addison's disease, and he was in no shape to play football with his more robust relatives and friends. History has come to round out the picture of John F. Kennedy, but on that morning, we would have agreed that we were playing the same game the President played in his family compound at Hyannisport, Mass. We were young and so was the President of the United States. That meant a lot to me. Many people today will consider Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Harry S. Truman or Dwight D. Eisenhower as their President. Others may have the same feeling about one of those who came later. For me, John F. Kennedy will always be my President. In 1960 five very important things happened in my life: I was hired by a newspaper, I was graduated from college, I turned 21, I was married, and John F. Kennedy was elected President. For me at least, the narrow victory of the Senator from Massachusetts was a comet blazing across the sky, signaling that the 60's were going to be good years, different years. The words now seem full of dust from the history books, but in those days people talked excitedly about ''vigor'' and ''charisma.'' John F. Kennedy was an attractive young President before the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, before ballplayers used hair dryers and appeared in underwear ads. In 1960 he was all the glamour we had, he and his wife who spoke French and looked terrific in an evening gown. The touch-football pictures were partly hyped; the photographs with John-John playing under his desk must have been staged. But after the musty 50's, after Ike, after a President who could not articulate outrage about segregation or Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, after a President who played a marginal athletic activity like golf, some of us were good and ready for a new decade. Then the Kennedys hit the stage like a tumbling act in the circus, full of blaring horns and rolling drums, and with lots of photographs of John F. Kennedy about to throw a sideline pattern to Bobby or Ted. Once in the summer of 1959, at a beach in Southampton, L.I., I found myself waist deep in the surf a few yards from John F. Kennedy. Politically, it was no thrill; we were Stevenson Democrats in my family. But a Presidential hopeful who had young- looking friends, who went to the beach on a Sunday, seemed pretty good to me. The Kennedys became associated in my mind with sports and crowds and youth and good times. One afternoon in 1961, in an amusement park in upstate New York, my wife was almost knocked down by Robert F. Kennedy, who was making a fast visit with his wife, Ethel, and some of their children. He stopped and excused himself before rushing on. In October 1963, covering a football game in Annapolis, Md., I was almost mowed down by Robert Kennedy, who was leaving early through the press box. The Kennedys moved fast. Starting adult life the same year the youngest President was elected set up a visceral sense of identification: the Kennedys lost a child; my wife went through a difficult but successful first delivery. I could only wonder why the dice had been rolled that way. In this anniversary month, many historians now criticize John F. Kennedy's actions toward Cuba and Vietnam; I will never be convinced he would not have been smart enough to find sensible options toward both countries. But his time, Malcolm X's time, Robert Kennedy's time, Martin Luther King Jr.'s time, and Allard Lowenstein's time all ended too soon. In the days after the shooting in Dallas, football twice added to my sense of loss and revulsion. The National Football League went ahead with its games two days later, while the President was lying in state, a gesture of disrespect I have never been able to forget. And a week later, on a train heading for the Army-Navy game in Philadelphia, I heard some whisky-slick officers and their wives talking too loudly about how they had never been able to stand the Kennedys in the first place. In the years since Nov. 22, 1963, many of us who came of age in the early 60's found no elected public figures to admire. Some of us admired the feminists and Bob Dylan's songs and Lech Walesa and Bishop Romero of El Salvador, and we could not help but notice that a Black Muslim boxer named Muhammad Ali did more to get us out of Vietnam than any President did. I mourn the loss of a President who seemed so intelligent and courageous and witty and youthful at the time. I admit that I keep up with bits of news about John F. Kennedy's children, and I root for Jacqueline Onassis in her battle for privacy. And I cannot watch young people throwing a football in a park without thinking of that day when the fiancee of one of the players came running across the grass to tell us something that would end our game. * * * (I still pretty much feel the same way. I remember the feelings of intense hatred emanating from Texas in the days before the Kennedy trip. I’ve come to have more mixed feelings about the Kennedy myths. He was more sick than we understood; also more personally reckless. I’m not sure he would have advanced civil rights and anti-poverty programs as much as LBJ did; then again, I think JFK would not have led us much deeper into Vietnam, but we will never know, and that is part of the sadness. My thanks to the Times for letting me express myself, then and now.) Ken Griffey was between seasons on Nov. 21, 1969. He had just hit .281 for the Reds’ Gulf League team – his first year in pro ball -- and was waiting to play in Sioux Falls in 1970. He did what made economic sense for a young man and his pregnant wife – they went home, which in this case was Donora, Pa.

Three generations have come through that hard town of zinc plants on the Monongahela River. Ken’s father, Buddy, was a great three-sport athlete at Donora High, whose teammate in basketball and baseball was a skinny kid named Stan Musial. Years later, Musial would softly let it be known he had no problem playing with or against African-Americans because he had grown up with them as teammates. Ken Griffey was also a three-sport athlete. Baseball was his weakest sport, but he signed with the Reds, and they taught him to hit. His first-born, Ken, Jr., happened to arrive on Stan Musial’s 49th birthday. They love that bond, the old Cardinal and the retired Mariner. Somewhere I have a gorgeous color photo of Musial in a gaudy sport shirt and Junior in a Mariner uniform, both smiling. It was taken by Dick Collins, who photographed generations of Hall of Fame celebrations. If I ever get the photo scanned, I’ll put it up here. Meantime, Junior and Musial are linked forever, albeit with a melancholy date. Stan the Man referred to John F. Kennedy as “my buddy.” They met one day in September of 1959 in Milwaukee when the campaigning senator from Massachusetts spotted the Cardinal bus, and sought out Musial, asking if he would campaign for him. In October of 1960, Musial went on the road for a week in what are now called Red States. He had a rollicking good time travelling with James A. Michener, Byron (Whizzer) White, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Jeff Chandler, Ethel Kennedy and Joan Kennedy. In the 2011 biography, Stan Musial: An American Life, another of the campaigners, Angie Dickinson, raves about the athlete who made everybody laugh. Musial always said he lost all nine states for the President, but it was more like 2-7. Musial and JFK met again at the White House before the 1962 All-Star Game. The President noted that people thought he was too young and Musial too old to ply their respective trades. They laughed about that, two guys who knew they had it pretty good. On Nov. 22, 1963, a lot of people did not feel like putting one foot after another, but Musial showed up at his restaurant and asked customers if everything was all right with their dinners. One customer who was there that night said he thought Musial showed up because people needed to see his familiar face. Truth or imagination, it was a nice thought. All of us of a certain age remember where we were that day. * * *. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch has a nice Thanksgiving feature on Stan the Man:: http://www.stltoday.com/gallery/sports/baseball/professional/reasons-why-stan-is-the-man/collection_052e6c5c-2516-56b5-b71d-4ae37a07c6e1.html#0 THIS JUST IN: DAVID VECSEY WROTE A SWEET MEMORY OF THE SUMMER WHEN HE AND JUNIOR WERE BOTH BEING PRODUCTIVE IN SEATTLE. http://idaveblog.weebly.com/1/post/2012/11/happy-birthday-ken-griffey-jr.html |

Categories

All

|