|

The Daily Miracle is waiting every morning at the top of the driveway, courtesy of a diligent delivery lady, who never misses a day.

Friend of mine at the New York Times plant in College Point, Queens, calls it “The Daily Miracle,” because it returns every day (with the collaboration of thousands of journalists in Manhattan, in Queens, and all over the world. This bundle in a blue bag is a miracle even though everybody knows young people don’t read newspapers, but there are enough of “us” who want to hold the paper in their hands and flip pages and peruse, peruse, peruse. (The plant also prints 50-odd dailies and weeklies – part of the miracle but also the foresight of the people who run the NYT.) Take this from an octogenarian who must have his fingers on “the paper,” there is another miracle in the journalism world – the ever-changing website of the same New York Times, thousands working around the world in all the continents and all the time zones. As we speak. Nothing like flipping electronic pages in the middle of the day to keep up with the judicial progress against the larcenous and bumptious Trumps. Or waking up and checking what has happened in the Middle East since the cut-throats came across the border to kill and kidnap on Oct. 7. We get the news and the embellishments from a great news-gathering organization (where I used to work), and that is a miracle because it took decades of insight and doubt and trial and error to save the blue-bag Daily Miracle but also to create the alter ego known as nytimes.com. The evolution of newspaper into the journal that never sleeps is documented in a new book, “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism,” written by Adam Nagourney, one of the many great reporters, who is still working there. For 43 years, I knew, I witnessed, I even managed to grumble and whine about the changes being foisted on us. (I do not do change well. I can provide witnesses.) I was around as a news reporter in the ‘70’s, when bulky and balky Harris terminals swallowed entire masterpieces after hours of pecking away at the keyboards, even though we had pushed, poked, whacked the “Save” keys. A living technology pioneer-saint named Howard Angione talked some of us out of our rages. Later there was another saint named Charlie Competello. Meanwhile, our bosses competed in their lairs. Some of them understood the online era at first and some did not. The book goes into Shakespearean length to show the decades of the long knives, over policy, over technology, and over flat-out human emotions. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”—King Henry the Fourth, Part Two, William Shakespeare. Top editors feared the managing editors they had just appointed and even publishers and family had a mix of human strengths and weaknesses. But four decades of friction came and went – and the NYT is in Ukraine and the Middle East and all over the United States. I’m not getting into personalities in this review. I just want to bear witness to the foresight and talent and perseverance of the owners and the editors and the reporters – and the readers. I had the honor of working for national editors Gene Roberts and Dave Jones and the great copy editors on that staff. I remember being assigned to the federal pen in Marion, Ill., where a lifer bank robber had completed his bachelor’s degree in a prison program. I turned in my article and copy editor Tom Wark called me and said, “This is not up to Vecsey standards…could you run this through the machine again?” I tried. The NYT had dozens and dozens of great editors like him. Later I worked for Abe (Rosenthal) and Arthur (Gelb) as a Metro reporter in the 70s. They could forget about you for weeks…but then they could give you an assignment that made you glad to be a journalist. (The end of the Vietnam War, 1973, as seen by cynical veterans in a steamy bar in deepest Queens, my choice of venue.) The computer age was under way when I returned to Sports in the 80s. Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, with his snarky sense of humor, held an occasional lunch meeting with us in Sports. One day I played grumpy-lifer and asked why the NYT needed the color that was starting to appear in the paper. The publisher said, as I recall: “We live in color. We dream in color. The Times needs color.” Look at the great reporting by Amelia Nierenberg and brilliant photos by Hilary Swift on grieving Maine in the past week. Of course, Arthur was right. The book describes how the Times dispatched long-time editor Bernard Gwertzman to bridge the gap between the traditional NYT and the infant Web-era NYT. One day, Gwertzman held a lunch with Sports types ad one of our many great reporters complained about his scoops going on line so early that his good pals on other major papers were poaching his work. Gwertzman was unflappable: “A year from now, we won’t be having this discussion,” he said. He was right. The reporter became a star in the Web age, too. (Recently, the NYT blew up its talented sports section. That decision will undoubtedly be in the next NYT history book.) But for now, Adam Nagourney has given Times readers (and Times lifers) a thorough view of the comings and goings of talented, driven journalists. I am in awe of the lavish meals and copious alcohol consumed by our leaders, often followed by sharp managerial decisions ...placed between career shoulder blades. Nagourney reminds us how long it took for female journalists and gay journalists to get a fair break to use their talents. Good for him. The editors argued and decided and changed courses. But somehow, somehow, The New York Times is better than ever, 24 hours a day. In print. Online. Either way, a daily miracle. ###

Using tango music and the physical concussion of boots stomping on the floor, the ballet follows the unwanted little girl who grows into a dance-hall performer who captivates Juan Perón. But she is followed by her childhood self, a waif in a plain white gown, who quietly materializes at key moments, to haunt Evita. Perhaps the best part of this ballet, from choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, is performed by the eyes – with camera closeups revealing the emotions of Evita, (Dandara Veiga), fearing her past will be revealed. My wife and I have decided that this ballet might be the best we have ever seen. *** I have always been something of a snob about TV -- soaps, game shows, series (i was obsessed with "The Sopranos.") However, while staying close to home in recent years, I have opened my mind, at least a bit. Every Saturday and Sunday morning, we seek out the Aerial America series on the Smithsonian channel -- hour-long views of the states. Sometimes we “visit” states we do not know very well – like New Mexico and Arizona. My wife, born in Connecticut, with genes from early settlers of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, loves the aerial views of New England. Today the series returned to Maine, which we discovered in the past decade from visiting her uncle Harold, who lived in Bath, a few yards from the Kennebec River, which he had helped dredge before World War II. Harold is gone now, but the Smithsonian cameras take us to coastal scenes so familiar we could taste the fresh catch at Bet's Fish Fry in Boothbay, A swoop over Brunswick showed the home of author Harriet Beecher Stowe near downtown Brunswick – with an old red-brick mill converted into urban offices and shops – “Look, there’s our Thai restaurant!” If we were a bit younger, if there were no Covid, we’d be visiting more of Maine, and other parts of this blessed continent. In recent months, we have seen documentaries of singers who have been part of our adult lives. Joni Mitchell was honored by the Gershwin award, at the Kennedy Center, beaming in the front row, as people praised her music, her idealistic messages. Joni has been recovering from a stroke, but -- spoiler alert: -- on this recent night, she agreed to go to the microphone and in an older, huskier but still blatantly Joni voice, she totally aced the Gershwin standard, “Summertime.” https://www.google.com/search?q=joni+mitchell+honored+at+kennedy+center&rlz=1C1GCEA_enUS874US874&oq=Joni+Mitchell+honor&aqs=chrome.3.0i512j69i57j0i512l3j0i22i30l4.18076j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:4cc10676,vid:C815lySYh9w Another documentary showed how Roberta Flack started singing classical music – not an easy path for a young Black woman -- and over the years how she took control of her own career. We try not to miss the series, “Now Hear This,” with American conductor-violinist Scott Yoo traveling all over the world to talk music with classical musicians. In all the fields I have covered, I have loved shop talk – from coal miners, from athletes, from politicians, who know their field and, if encouraged, will divulge tricks of the trade. The other night, Yoo explored how Robert Schuman may have been bipolar, interviewing a doctor/musician who can talk and play Schumann. Finally, CNN has been running a series with the actress, Eva Longoria, exploring the food of Mexico, region by region. Longoria, born in Texas of Mexican ancestry, visits contemporary restaurants in Mexico City and is at her best visiting the countryside, chatting respectfully with the earnest women who farm and cook and also trek into the cities to sell their wares.

Recently, Longoria was in the Yucatan peninsula, not just Merida, but the tidal flats where she learned to sift for salt. She also watched the deliberate process of the regional specialty -- baked pork, cochinita pibil -- in a covered pan, underneath a layer of dirt, overnight, for 8 to 12 hours. https://www.cnn.com/videos/travel/2023/03/06/yucatan-mexico-cochinita-pibil-eva-longoria-origseriesfilms.eva-longoria-searching-for-mexico It’s been two decades since I’ve been to Mexico – a soccer match against the USA. It brought back memories of reading travel adventure books by Richard Halliburton in grade school. (Longoria did not mention the human sacrifices into deep wells that Halliburton explored so many decades ago. ) Longoria’s series makes me want to go back to all the places I've visited -- Puebla, Monterrey, and next time Oaxaca. For the moment, I’m thankful to contemporary television for the documentaries that take us so many places, At the moment, Sunday afternoon, TV will take me to another corner of the world -- Oakland, A's vs. Mets. Ever since Roger Angell passed last week, friends have been e-mailing about how great he was, and asking how well I knew him.

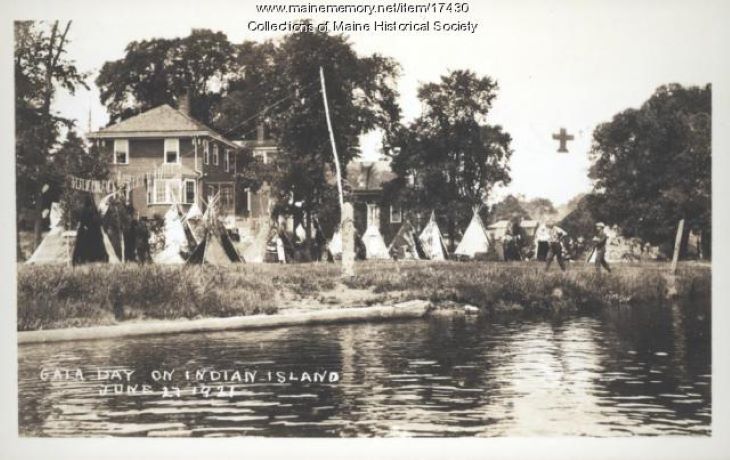

Let me say, he was grand company in a pressbox watching a game. I always thought he seemed liberated by his mid-life discovery, his strange hobby, writing about baseball. It began as his left-brain, right-brain activity, when he wasn’t editing temperamental fiction writers or conducting in-house business at the New Yorker or dealing with the vicissitudes of life. He enjoyed the hell out of this other world, and it showed. He also loved paddling his kayak or sailing along the Maine coast when he wasn’t writing about Pete Rose or Reggie Jackson or the baseball denizens of the Pink Poodle, his hangout in Arizona during spring training, or editing what any sportswriter would respectfully call “real writers.” Now and then, he would pop into Yankee Stadium or the Mets’ ballpark, without the weary pack-mule trudge of the beat writer or old-fashioned sports columnist (been there, done that) lugging a laptop, expected to produce profundity on deadline, halfway through the season, 81 up, 81 to go, plus the endless autumn trek. As we all said in our alibis for why we were not Roger Angell: we had deadlines. While we were pecking away, he could hang back and chat up a ball player who grasped that this older guy knew the game and was not looking for a few quick quotes. I admired the working friendship he developed with, let’s say, Dan Quisenberry, a submarine-style relief pitcher with the Kansas City Royals, who was cool enough to explain his technique. Roger also took seriously the first female writers in the press box and – gasp – the locker room, who were professionals, just like men, if you can imagine. So, how well did I know him? I got off to a dumb-ass start. It must have been 1968 when I sat next to a guy near 50 and we introduced ourselves and he said something about “New York” and I thought he meant the new weekly magazine so I wished him luck with the new publication. To his credit, he did not correct me, nor did he back away from this dolt. Later I deduced that he wrote for the New Yorker and began subscribing, not just for his occasional baseball pieces but for the great eclectic literacy of the magazine. I still subscribe to the New Yorker in the age of Editor David Remnick – a great guy who started as a daily sportswriter, for goodness’ sakes. The arrival of the New Yorker—the print version – is a highlight of this pensioner’s life. Did I learn anything from Roger Angell? The best part was the way he thought independently and observed the sub-marginal things and had the time and space and license to elaborate. Plus, he had talent -- could play with themes and details, knowing exactly what he was doing. He was a model, but then again, in our collective world, no journalist should lack for models. My parents were journalists and I came along in the pioneer Newsday sports department in the 60s, with crusty old editors and the new breed of chattering younger types, known as Chipmunks. And then there were books that made me want to write longer and better. In the early 60s, I sought out “Bull Fever” by Kenneth Tynan, a London drama critic who roamed to the corridas of Spain, or “Cars at Speed,” by Robert Daley (son of the noted Times columnist, Arthur Daley), who had bolted to Europe to write about the Grand Prix – and life in the old world – and ignited my wanderlust. In the same period, I read “Night Comes to the Cumberlands,” by Harry Caudill, a lawyer from an old Kentucky family, whose lament for the defaced mountains made me want to go to Appalachia and see what was left. So many great writers, out and about, dealing with current issues, from their heart, from their eyes, from their brains, writing at entertaining length. Over the decades, I was always happy to spot Roger Angell in the press box. I cannot remember what we talked about, but it was fun. When I retired at the end of 2011, I kept up by phone when I particularly loved something he had written, and I called when he had a death in the family. When my wife and I started visiting her elderly uncle in coastal Maine, I called to tell Roger how much we loved his other world. My wife says I should have told him that some Angells popped up in her sprawling family tree from New England in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Finally, a confession: Every year, readers would look for Roger’s annual Christmas poem, hailing and pairing people with exotic and yet topical names. For decades, every December, I scanned the poem for my name, but it never appeared. I never told him how sad I was. Other than that, Roger Angell was, just as you imagined, great company as well as great reading. * * * In case you missed: Obit by Dwight Garner: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/sports/roger-angell-dead.html Tyler Kepner’s appreciation: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/23/sports/baseball/roger-angell.html And a labor-of-love sampling of Roger’s work, from Lonnie Shalton, lawyer in Kansas City and a true lover of baseball: http://lonniesjukebox.com/hot-stove-192/ It is dawning on me that the United States will never truly acknowledge the civilizations that were disrupted and ignored on “our” quest to take over a continent. People who arrived here as slaves are one issue; I am talking here about the people who were here first – Native Americans, indigenous people, “them.” The examples of ignorance just keep on coming. I am thinking of some highly moronic words by Rick Santorum, a former senator from Pennsylvania, who has no respect for the civilizations that existed for many centuries before Europeans arrived. I am also thinking of a stirring article in the April 19 issue of the New Yorker about an academic who spent a lifetime studying the language of the Penobscot people in Maine, helping save the language, to be sure, but in the end not giving a penny of his sizeable fortune to the Penobscot cause. Let’s start with the blather from Santorum, who served two terms in the Senate, and recently spoke at the Young America’s Foundation “summit,” which was titled, “Standing up for Faith and Freedom.” But whose faith, whose freedom? “There was nothing here. I mean, yes we have Native Americans but candidly there isn’t much Native American culture in American culture,” Santorum said. Questioned about it, Santorum yammered on a bit. Never mind: we have had seen into his dark and ignorant heart. “Rick Santorum is just saying what the majority of Americans silently believe – the only ‘real history’ is US history,” said Brett Chapman, a Native American attorney and descendant of Chief Standing Bear, the first Native Indian to win civil rights in the U.S. “Everything centers around it,” Chapman added. “Many claim to appreciate and respect Native history yet know nothing about it. Let’s not act like he’s some lone wolf out there on this.” I looked it up. Santorum’s father, Aldo Santorum, was an Italian emigrant, from Riva del Garda, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, and his mother, Catherine (Dughi), was born in Pennsylvania, of half Italian and half Irish ancestry. As a proud carrier of an Irish passport, via my late grandmother from County Waterford, I think I can safely say: Irish and Italian immigrants were scorned by Anglo settlers who had already begun smugly looting North America, with God on their side. As of today, Santorum still has his paid forum with CNN. * * * The other example of disrespect of Native Americans is the article by Alice Gregory in the New Yorker: “How Did a Self-Taught Linguist Come to Own an Indigenous Language?” Gregory describes how Frank Siebert, a quirky scholar, became fascinated with the dying language of the Penobscot, whose reservation is based on Indian Island in the Penobscot River in Maine, north of Bangor. Siebert arrived on the modest ferry from the mainland, sought out an elderly keeper of the language, and began keeping records by his own quirky methods. Admirably, Siebert hired assistants like Carol Dana, a member of the tribe, who shared his interest and energy. Leaving his wife, Marion, and two daughters behind, he was based on the island, cataloguing the language but apparently without forming the bond or identity with the people. The research and the memory of Carol Dana, now 70, , inform this stunning article, nine pages long, which I devoured in one sitting, and which I recommend most heartily.

When Siebert died on Jan. 23, 1998, Gregory writes, his collection was auctioned off by Sotheby’s: “The sale brought in more than $12.5 million. As stipulated in Siebert’s will, his daughters split the sum. Each bought a house for herself, and together they bought one for Marion. No provision was made for the Penobscot people.” Gregory drily notes that Siebert “bequeathed his dictionary and his field-work materials to the American Philosophical Society, a scholarly organization, founded by Benjamin Franklin, in 1743, which is housed in a stately brick mansion in Philadelphia, a nine-hour drive from Indian Island.” Gregory also notes that the society retains the intellectual property rights, and that visiting hours and conditions are rigidly controlled. She adds: “In copying down the grammar, the stories, and the vocabulary of the Penobscot, Siebert made them his. In dying, he made them the American Philosophical Society’s.” Siebert’s lack of generosity, the absence of respect, sounds cold, However, former Sen. Rick Santorum, no doubt speaking for a huge segment of the white majority, could reassure us all, there was nothing much in the Native American culture when we invaded, and surely there is nothing worth bequeathing to the Penobscot people now. ### Alice Gregory’s article in The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/19/how-did-a-self-taught-linguist-come-to-own-an-indigenous-language The Guardian's article about Santorum's ignorance: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/26/rick-santorum-native-americans-comments-outrage-cnn Uncle Harold took us on great drives around coastal Maine – the beaches, the woods, the little towns.

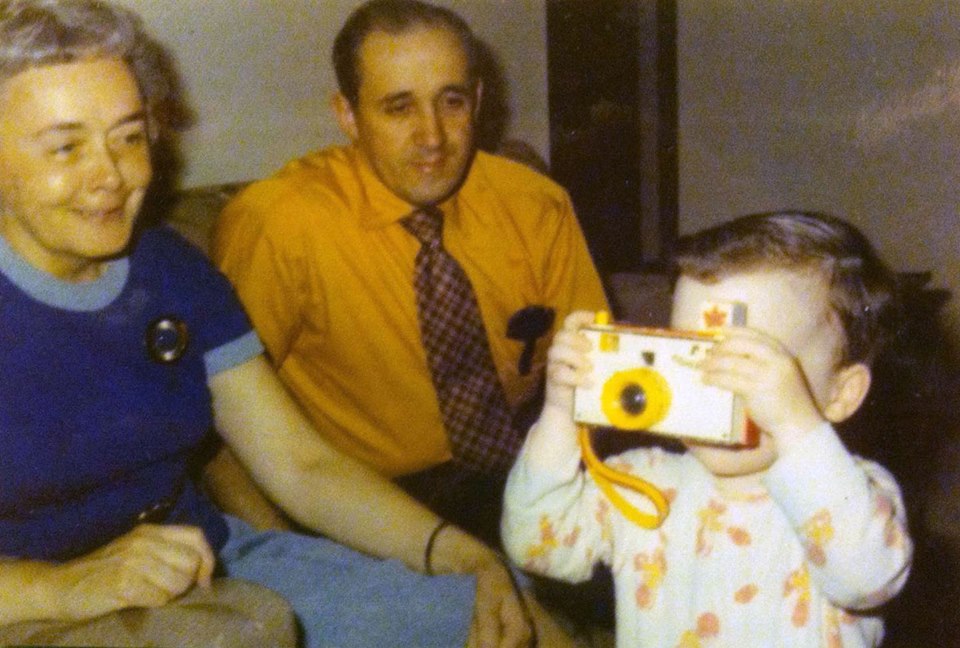

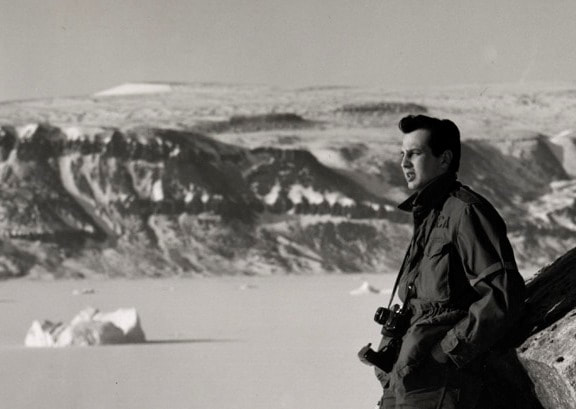

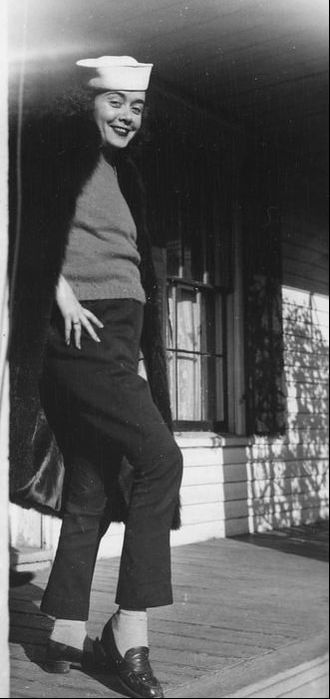

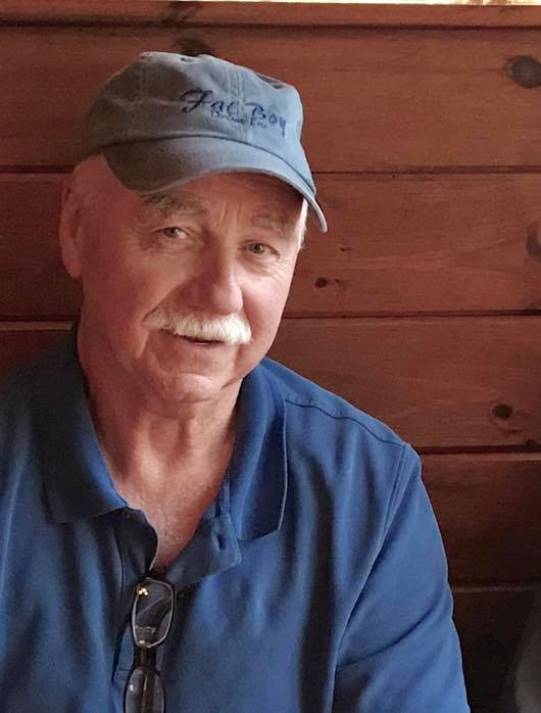

The tours invariably ended near Oak Grove Cemetery in his home town of Bath. “Why don’t we just drive in,” he would suggest. We would park on the narrow lane and walk to the single tombstone for his wife Barbara and their son Roger. Harold’s name was waiting for the date of his death. Roger had died in a car accident near home, after surviving a bullet and malaria in Vietnam. Barbara had lived a long and active life, caring for others, although wracked by bone disease and later diabetes. Harold often talked about her in the present tense, as in “Barbara and I take this road to Boothbay Harbor for the fried fish.” My wife, his niece, and I started visiting Harold Grundy after Barbara passed in 2014. We fell in love with that part of Maine, and at my own advanced age I found myself a new hero, as he casually told stories about surviving combat in the Pacific and building electronic surveillance outposts in Greenland and Guantánamo Bay. But he was wearing down, and it took a village of loved ones to usher him through pain and confusion before he passed on Jan. 4. People in cold climates cannot bury their dead in mid-winter. Harold, stubborn by nature, modest from his Quaker background, precise from his construction career, specified no ceremony, no fuss, for his burial. His two faithful surrogate children, Ace and Cookie, now living in Arizona and Connecticut, arranged for a no-frills burial on May 11. Eric came in from Florida. My wife and I were asked to represent the family, scattered and getting on in years. A few locals heard about the burial, and then a few others, and they got to the cemetery, some using walkers and canes to reach the casket, with the American flag neatly folded on top. The sun was bright, the breeze was chilly, and the funeral director read a few prayers -- as quick and simple as Harold had mandated. A very fit military guy in a red flannel shirt, who had worked with Harold at the surveillance base in Cutler, Me., stood at attention and whispered to me: “Best man I ever met.” Later, eight of us met at a tavern alongside the glistening Kennebec River. We toasted the family, and told a few stories. Ace told how Barbara and Harold used to take him along on so many family outings when he was a kid. And Ace told how Harold approached the mathematical challenge of building basement stairs: “He wasn’t telling me what to do. He was teaching me.” People smiled as they recalled how Harold always had fresh pies and pungent chowders on the stove for company. My wife, the oldest of her generation, remembered a Christmas right after the war, when three young couples were sharing a small house on the Connecticut shore, and how she witnessed Uncle Harold using a tiny saw on a wooden bowl. On Christmas morning, she found a beautiful bed for her doll’s house. Harold always made things. He and Barbara used to peddle his home-made toys at flea markets in the region, and later his friend Eric made a thriving web business out of wooden objects. Nobody wanted to leave the lunch. Cookie, so loyal and capable, who did the paperwork for Barbara and Harold for decades, proposed that our little community meet again next year. We went our separate ways, knowing that Harold was up on the hill at Oak Grove Cemetery, with Barbara and Roger. * * * I’ve written about Harold and Barbara and Maine: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/farewell-to-harold-grundy-of-the-greatest-generation https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/sometimes-a-good-idea-actually-works-out https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/dredging-the-river-in-1941-for-a-destroyer-in-2016 My wife’s uncle, Harold Grundy, passed early Thursday at the age of 95. He was an American hero – a carpenter who learned complex engineering skills, who kept Navy ships steaming in murderous waters in World War Two and later supervised the building of observation stations and nuclear plants. He was a survivor – of bombs in the Atlantic and Pacific, of winters in the Arctic, a wartime storm off England, a typhoon in the Pacific, and of life itself. His only child Roger came home wounded from Vietnam only to die from a car wreck on a Maine highway. His wife Barbara was wracked by diabetes -- and he took care of her, with the help of dear friends. Everybody knew him in Bath, Maine, Barbara’s home town. After Barbara died in 2014, Marianne recognized the need to visit her uncle once in a while. At 93, Harold would have thick, rich chowder on the stove and fresh fruit pies baking in the oven. Harold would take us on little outings from Bath – beaches and fish restaurants and back roads. He took us to coastal towns that looked like a setting for “Carousel” and fish-fry stands and old forts. He talked about Barbara in the present tense: “Sometimes Barbara and I drive up this road in the late afternoon.”

His education had ended in high school. He and his older brother left Connecticut in 1940 for a job dredging the Kennebec River to accommodate the large warships being built for what was coming. From his cottage alongside the river, he would tell us about rowing explosives into the middle of the river. In wartime, his acquired technical and engineering skills were essential to the military; he helped win one war and fight the Cold War. He was the last survivor who had served at observation posts in Greenland and Cutler, Me., and Guantanamo Bay, keeping an eye on our new best friends from Russia. However, because he was technically a civilian employee (ducking the same bombs as the military personnel), he was denied a pension by the U.S. government. Somehow, he was not bitter. Harold moved all over the world, building sensitive structures. Recently, we mentioned that one of our daughters lives near the nuclear plants at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. “Don’t worry,” Harold assured us, “I can tell you we made them double strong.” He had a Zelig-like way of being everywhere. He once chatted with a young senatorial candidate named John F. Kennedy in a train station in Boston; Winston Churchill popped out of No. 10 Downing Street and said hello to Harold and a few other tourists. One time we were driving near the coast and Harold casually mentioned he had helped build a house for Margaret Chase Smith when she was a senator. With her politician’s memory, she once recognized him when she got off a government plane at Cutler, and asked him to accompany her on her visit. People seemed to detect the civility and knowledge behind his humble bearing. He was so valuable to a construction company that they often flew Barbara to join him overseas, and they helped with her medical treatment. When Harold was home in Bath, between projects, he and Barbara, with her crippling diabetes, expanded a house on Washington St. He built houses and boats and docks and staircases for banks and chicken coops that were more handsome and sturdy-looking than some homes along the highway. Harold and Barbara started a little woodworking business – in their spare time, you understand – which has become a major business for a close friend. Harold and Barbara had a legion of dear friends who helped them: Cookie, Ace, Eric, Martha A, Martha B, Ann, Germaine, Diane, Rich and Suzanne, Bill, his nephew Dr. Paul, many caring medical people in the area, Kristi at the Plant Home, and people in shops and banks and drugstores, who fussed over them, in a real community. Two years ago, the Peary MacMillan Arctic Museum & Arctic Studies Center at nearby Bowdoin College held an exhibition of 193 photographs Harold took when he was based in Greenland. Harold’s family – including siblings in their 90s and late 80s – came in from New England and Florida for a reunion, in Harold’s most public moment. Harold came from hardy stock -- Quakers named Watrous and Crouch and Whipple who settled the eastern Connecticut coast and people named Grundy and Clegg and Schofield who thrived in Lancashire during the Industrial Revolution. But even these rugged folk wear down. Harold was fading the last time we saw him, on his 95th birthday in September. He had moved into a lovely retirement home, but his energy was gone and he could not enjoy the party. On Wednesday night, Cookie, a surrogate daughter to Harold and Barbara, who supervised their paperwork, was visiting from Connecticut, to be near him. Harold passed as a wintry storm roared up the coast. Come spring, Uncle Harold will be interred in the lovely hillside cemetery where he used to take us to visit Barbara and Roger. In recent weeks, as I thought about Harold and Barbara and Roger, my mind moved to a song about the release from pain – “Agate Hill,” by Alice Gerrard, recorded by the great Kathy Mattea. As I type this in the snowstorm, I think of Roger and Barbara and Harold together, building and cooking and fishing on some celestial version of coastal Maine, and I hear a line from the song: “Wild and free again, oh it will be as then.”  IN MEMORIAL, GERMAINE BOYNTON Harold often talked about his in-law Germaine who lived further up US 1. She invited us to lunch last spring and cooked a French-Canadian specialty and showed us the work and studios of hers and her daughter Diane, two formidable and artistic ladies. Germaine passed in hospice Saturday morning, two days after Harold. All through this long holiday period, I have been thinking of people who set an example for the rest of us.

Now I wish I had not found this one. In the final week of an unsettling year, a young soldier – an immigrant, yes – risked his life once, twice, three times, four times, to save people in a horrendous fire in the Bronx. And then he went back a fifth time and did not survive. A week before, I had filed my final post of the year -- a reminder (to myself) to light a candle rather than curse the darkness. (Whole lot of cursing going on.) Emmanuel Mensah from Ghana personified the selflessness we all like to think we could demonstrate, if we had to….if it presented itself…. I came up with other examples, people I actually know. My friend Mendel of Jerusalem is a rabbi and family therapist (and writer, and runner, and Mets fan from Queens) who volunteers as a counselor with EMT units. We met for lunch on Long Island during his home visit. He told me that while trained medics deal with the physical part of a crisis, Mendel finds anybody who needs support. He never knows what language or accent he will hear when he takes somebody’s hand. They could be Jewish or Muslim or Christian. He does not care. He ministers. He lights the candle. Then I thought about my wife’s uncle Harold from Maine. He recently turned 95 and can no longer have home-made fish chowder and pie waiting for us when we drive up U.S. 1. Harold says he would like to be “with family” – aging, scattered -- but his “family” is right there in Bath, where he has lived most of his life. There is Ace, a surrogate son who returns regularly from the Southwest, and Cookie, a surrogate daughter who drives up from southern New England; they have skillfully handled the complicated details of a loved one who lives a very long time. There is Eric, whose family has been intertwined with Harold and his late wife Barbara. There is Martha, who drives Harold to the doctor even as she works full-time. There is Ann, the friend and nurse who has given diligent counsel. There is Germane and her daughter Diane, and Rich and Suzanne, and Bill, an in-law, and Kristi, retired Army colonel and nurse, who watched over Harold in a lovely retirement complex, as long as it was feasible. We have witnessed the best example of a classic American town, actually bustling with work (building warships on the Kennebec River, which Harold dredged in 1941) and the good will of people who know who they are, where they are from. But let’s double back to Emmanuel Mensah, from Ghana. The Times says he joined the Army National Guard and recently passed basic training. He planned to go on active duty, but before he did, there was a fire in the building. At the end of a dark year, I visualized Emmanuel Mensah’s military training – the preparation to protect people, to back up your buddies, to serve. In the months to come, I count on that developed impulse to follow rules. I suspect Emmanuel Mensah’s fine instincts as a human being, from his homeland of Ghana, were encouraged by the American military: when bad stuff is happening, go toward it. Emmanuel Mensah, an immigrant, saved lives in his final minutes on this earth. In the new year, his example shines.  Harold Grundy has visited 66 countries and 49 states. He likes to tell people about the construction he supervised in top-security places like Greenland and northern Maine and Guantanamo Bay. He also ducked bullets and bombs in Europe and Asia while delivering goods during World War Two. Whenever he and Barbara came home to Bath, Maine, they updated the pins on the map – which became the summary of his grand life, soon to reach 95 years. Barbara has been gone for a few years, and recently Harold – my wife’s uncle – began to need more care. He was in the right place – a cottage on the grounds of The Plant Home, alongside the Kennebec River, a 100-year-old retirement home, beautiful and comfortable, idealistically designated for people from the region. Harold held on by himself as long as he could, but when he began to need more care he was moved to the main house. The staff was fussing over him – everybody fusses over him – but he was feeling the huge change, even with a private room overlooking the river he dredged in 1940. How to deal with the tremendous sense of upheaval in his life? Harold is surrounded by good friends from Bath, a real town with thriving shipbuilding and generations of people with long memories and loyalties. Ace, his faithful surrogate son, has been visiting from Arizona. Cookie, a loving surrogate daughter and friend of Barbara’s, has been driving up from Connecticut. Ann, a retired nurse, has been volunteering her expertise. And Martha has been offering rides to doctors. Eric takes him out for breakfast. Dr. Paul, a nephew, has popped in, from his peripatetic life. This is the essence of community. We should all be so lucky. Still, understandably, Harold was having trouble adjusting. Ace and Cookie agreed that he needed more personal touches in his new room, but he was divesting traces of his life, including the map, with all the blue and green and red thumb tacks. The other day, my wife and I dropped in to meet the director of the Plant Home -- Kristi Hyde, a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, who served several active nursing tours overseas. This was our first meeting. Ms. Hyde invited us to sit at her desk. She sat squarely and leaned forward and looked my wife in the eye and asked how she could help. I had a flashback to three years in ROTC in college, when we were taught the fundamentals of leadership. (The military knows how to teach responsibility – thank goodness, I say.) Marianne said: “Harold has this map in the cottage…” Ms. Hyde smiled and said (as I recall), “We need to get that over here.” Twenty-four hours later, that large map (with the wooden frame that Harold, a master carpenter, had built) was placed on a wall outside the home’s activities room, where people pass all day. We took him downstairs to show him, and told him Ace and Cookie and Kristi Hyde had wanted that map to be with him. Harold smiled – and pointed – and began telling us stories about a few of his postings – Jamaica, Nigeria, Three Mile Island, and the perilous missions during World War Two. We stayed 15 minutes. There are always new stories. We’re back home now, and Harold is reportedly adjusting to his room squarely facing the river he helped dredge in 1940. He often tells how he ferried explosives into the middle of the river to help the blasters. His life keeps rolling, alongside the Kennebec. When Harold Grundy helped dredge the Kennebec River in 1941, he knew how deep the channel was, and where it ran.

Harold Grundy – my wife’s uncle – still lives alongside the Kennebec in Bath, Maine. Just a mile up river, the Bath Iron Works has just finished the newest and biggest American destroyer, the $4.4-billion U.S.S. Zumwalt. From the back window of his cottage, Uncle Harold has watched the behemoth on test runs. Recently, he read in the paper that the skipper of the Zumwalt, the marvelously named Captain James A. Kirk, was curious about the history of the dredging of the river. At 94, Harold remembers it all – how the workmen lived in modest cottages near the river, how he carried dynamite in a primitive pickup truck along a bumpy dirt road, lifting 100-pound packs onto a modest skiff and ferrying it out to ships, whose drill shafts went 90 feet deep, loosening thick slabs of rock. They went out in almost all weather, sometimes sleeping on board, helping dump the excess rock far out at sea. After the river was dredged, Harold worked for the Merchant Marines, ferrying ammunition, serving in murderous combat in the South Pacific as the ship’s carpenter, ubiquitously called “Chips” by the sailors for the sawdust and slivers produced by their labors. He saw ships blown to bits all around him, saw sailors on stricken ships waving a solemn goodbye as they went down. When the war was over, the Merchant Marine gave him a handshake but because he was technically a civilian he receives no military pension. Oh, well. He worked for the military for many decades, helping build high-security structures all over the world. Last year, nearby Bowdoin College honored him with a show of the photos he took in Greenland and other sensitive places. I wrote about it: http://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-heir-of-quakers-who-kept-his-country-safe Living alone since the death of his beloved wife Barbara, Uncle Harold read about Captain Kirk’s admirable curiosity and wrote him a letter, sharing the copious details in his memory. A few days later, Captain Kirk paid a visit to Harold's house, a mile from the Bath Iron Works, but Harold was out running errands. The captain left a unique gift -- a handsome peaked cap, dark blue with gold braid, and the name of the U.S.S. Zumwalt printed across the front. On the back was the name: Hal Grundy. Uncle Harold keeps it inside, in a large clear baggie. It’s not for all weather. The Zumwalt left Bath on Sept. 7, heading toward San Diego and points beyond. Uncle Harold will follow her progress, knowing that he helped get her from the Bath Iron Works out to sea. Well done. We drove up to visit Marianne's uncle Harold, 94, last October. Recently we returned. We wonder why it took us so long to discover Maine. Every time I turn the wheel, the view changes. The people are individuals. It reminds us of Wales, another singular place we love. That is high praise. Friends from Long Island invited the three of us to their stone house on an inlet. Lena made an amazing Swedish specialty from fresh salmon and eggs and dill. Claes harvested rhubarb growing since they came here. (below) Harold has been living on the same street for 70 years, since he met Barbara when he came to help dredge the Kennebec River, which flows behind his home. In between, he helped build facilities for the military. (His photos were recently displayed by nearby Bowdoin College.) About 60 years ago he gave away one of his yellow construction helmets. Recently, somebody gave it back. People have histories in Bath, Maine.

|

Categories

All

|