|

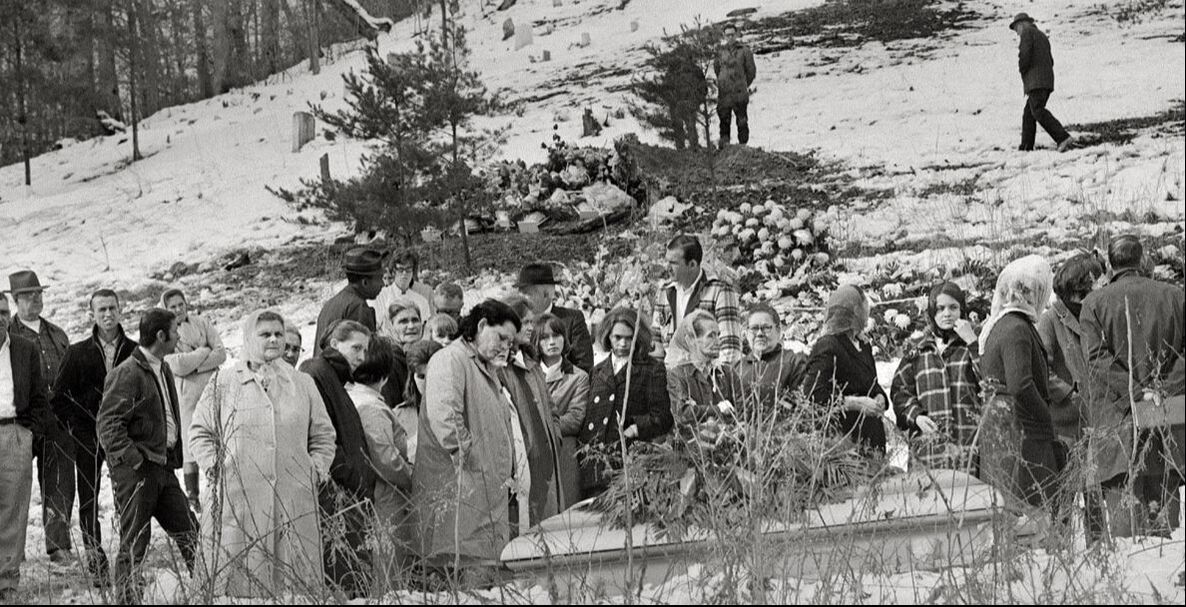

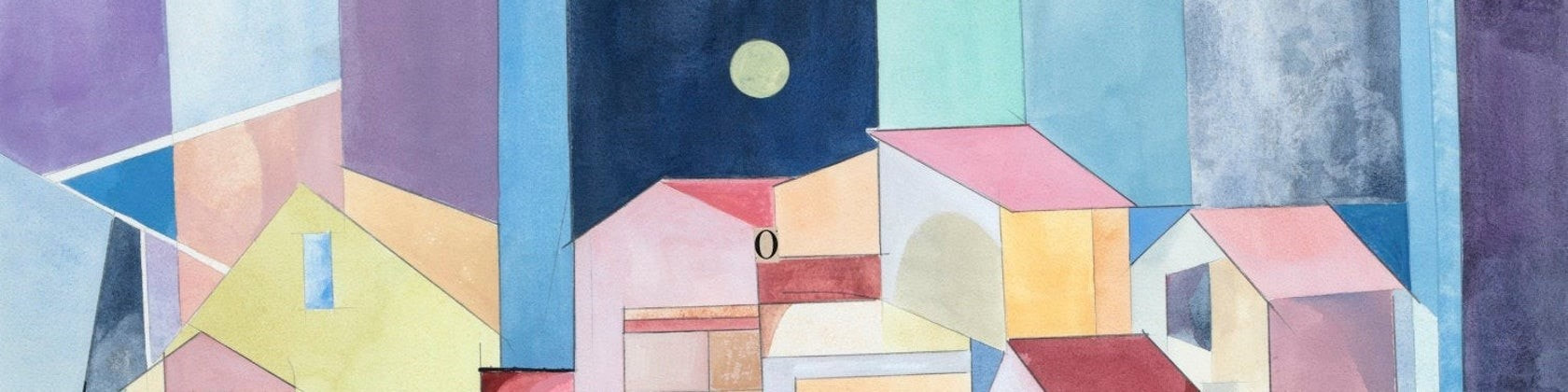

"There are 9,388 graves in the cemetery, most of them in the form of white Latin crosses, a handful of them Stars of David commemorating Jewish American service members. As antisemitism rises again in Europe, they seem somehow more conspicuous." ---Roger Cohen, The New York Times. "D-Day at 80" -- June 6, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/06/world/europe/dday-80th-anniversary-veterans-remember.html Marianne Vecsey noticed the same thing, back in the mid-70s, when we drove with our young children to Normandy, in the sweet damp spring. Part of Marianne's ancestry goes back a thousand years to Normandy, but this was not about us. This was about the Allies who died during the invasion, now 80 years ago. We live in New York; we tend to notice stars amidst the crosses. "You hear the number, but when you stand there, and see the graves with crosses and stars, it sinks in. It's stunning, actually," Marianne said on D-Day 2024. Roger Cohen had the same reaction. Of course he did. Roger is one of the greatest Times writers of any generation -- fearless, perceptive, the voice of the underdog, the champion of the fallen. I've spent great times with Roger running around Germany during the 2006 World Cup or watching him suffer for his Chelsea F.C., in some New York pub. I've read his poignant tribute to his mother, to all who suffer, in his 2015 book, "The Girl From Human Street." https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/22/the-girl-from-human-street-review-roger-cohen-memoir-motherodyssey-of-loss I miss him in New York -- Brooklyn, to be specific, but now he is right where he should be, in the middle of it, as Paris Bureau Chief, preparing his masterful text for the 80th "anniversary." Marianne and I and "the kids" made the same pilgrimmage north from Paris, borrowing a friend's chugging sedan, heading toward the tangy air of salt water, toward Mt. St. Michel. (I had learned to love Mt. St. Michel, reading Richard Halliburton in grade school.) Now we were there, in a scruffy little gite near the beaches, in a spring so damp that sheets did not dry on the line. We saw the Bayeux Tapestry, of course we did, and then we headed to the beach. Funny, as we sat atop one of the sandy cliffs, we heard distinct German voices behind us -- three cars, three sporty couples, no longer the enemy, just modern Europeans on spring holiday, to see the Normandy beaches, the landing now three decades in the past. We took in the logistics of that landing, what it was like to be in those landing craft. The only person I knew who had been in one of those boats was Lawrence Peter Berra of St. Louis; but Yogi never talked about it, just as his teammate Ralph Houk barely alluded to his battlefield commission at the Battle of the Bulge. Veterans don't talk much. Marianne learned that when she was a lifeguard at a village pool on Long Island. Some of the older town workers had been in the war, but never shared details. Now it is 80 years, and centenarians will talk, particularly if a master journalist like Roger Cohen asks the right questions, the right way. People talk to Roger. Read his words; look at the photos. Marianne stored the visual memories, the visceral impact, of the Stars and the Crosses. She's an artist -- has a lifetime of paintings out there.

We loved our April in Paris, staying in a sous-sol in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The Metro. The Louvre. The Bois. Then we came home and resumed normal lives, and one night Marianne waited for the family to go to sleep, and she painted her geometric tribute. This month Roger Cohen has been, as always, in the right place, recalling the Canadians, the Europeans, the Americans, who stayed behind, in Normandy. For decades, they were teammates in the sports pages of that great paper, Newsday.

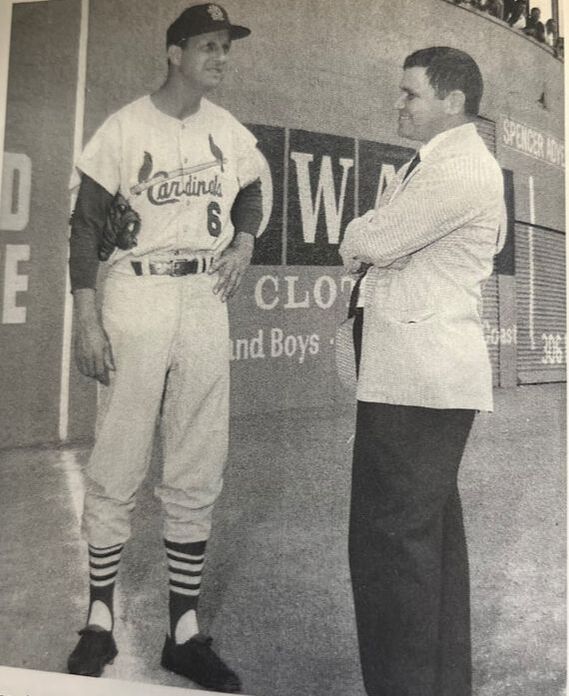

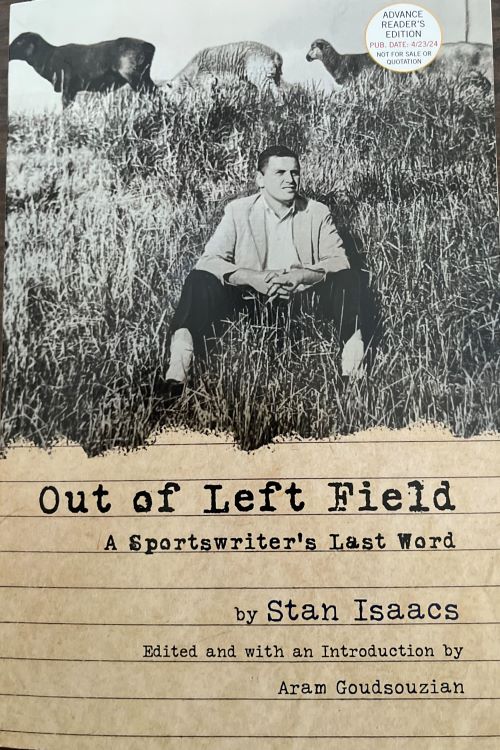

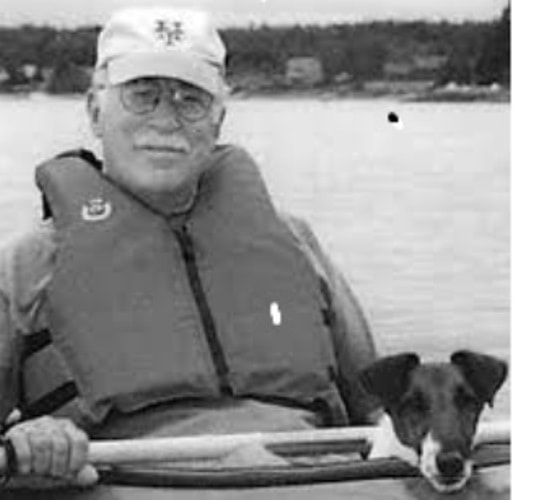

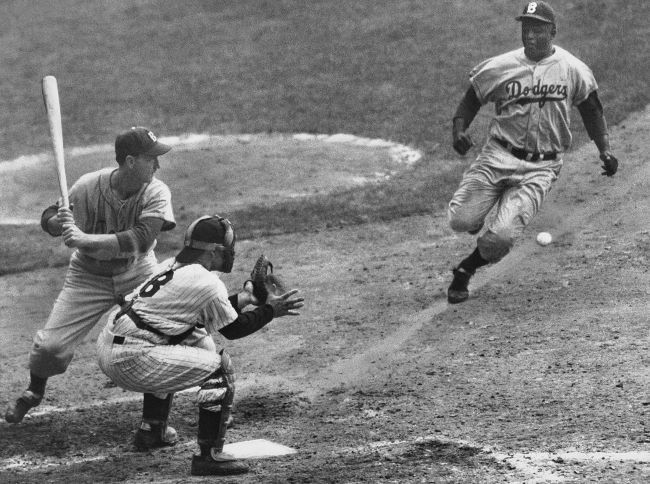

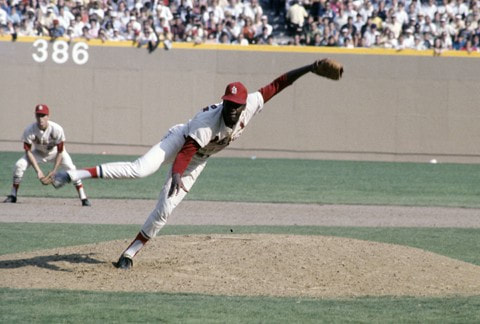

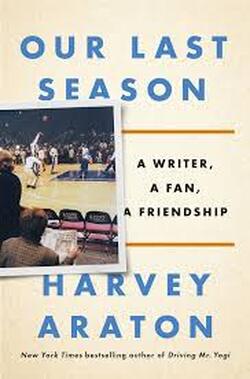

Steve Jacobson could cover anything, and ask probing questions, Stan Isaacs saw life from his natural position – way out, left field. They were my colleagues and my friends and my inspiration when I worked at Newsday in the 60s. We even played touch football together. Stan passed in 2013 but his words are being revived in an autobiography, “Out of Left Field: A Sportswriter’s Last Word,” to be published in April by the University of Illinois Press. Steve is very much with us in a current podcast celebrating a magnificent book he wrote in 2007: ”Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The Players Who Integrated Baseball – and America,” by Lawrence Hill Books. Steve’s book is, alas, out of print at the present time (as Casey Stengel used to say), but just in time for Black History Month, Jacobson -- known as Jake -- has been celebrated in a podcast by Steve Taddei, from his perch in the Bay Area. “I found ‘Carrying Jackie's Torch’ at the public library,” Taddei wrote in an e-mail. “The book fit in well with ‘Leadership Lessons From the Negro Leagues,’ because it gave me perspective to the adversity my heroes of the 1960's and 70's went through and overcame on their journey to the Major Leagues.” It is no secret that the evils of segregation, which kept Black players out of “organized” ball were not magically dispersed by Jackie Robinson’s first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Robinson took the first curses from opposing dugouts, the blatant reluctance of some Brooklyn teammates, and the daily problems of living in a considerably racist nation. And it was still going on when Steve Jacobson was interviewing players in the 60s. One of the most approachable was Jim (Mudcat) Grant, a star pitcher, who one day challenged Steve to expand his questions: talk to other Black players who ran into the walls of segregation. Years later, that’s what Jake did – hearing how Black players at first could not stay in hotels with their white teammates, how they had to eat brown-bag lunches in team buses, how Black players felt underrated by their managers and teammates. Always a dogged reporter, Jake sought out players we knew from our working years --Tommy Davis who always greeted writers from “my hometown” of Brooklyn, Ed Charles, the spiritual center of the 1969 championship Mets, Bob Gibson, the great pitcher who used his hard veneer to keep hitters – and reporters -- at bay, and Dusty Baker, whose winning personality has carried him to an enduring career as manager. Henry Aaron. Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby. In this podcast, Steve Taddei spoke by phone with Jake (and me, a little) and near the end, Anita Jacobson, Jake's wife, tells about the hotel pool in Florida, where the Mets took spring training, circa 1965. The formidable Anita -- who cooks, and teaches cooking-- recalls what she and my wife Marianne did when another white mother pulled her child out of the pool rather than share chlorine water with a Black child. Life was like that for the Black baseball people who carried Jackie’s torch. Steve Jacobson worked hard to get memories of the Black players, and now Taddei has honored what Jacobson did in his book. Here’s the podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/leadership-lessons-from-the-negro-leagues/id1646816110?i=1000644226588 *** And here is the glorious scoop of the day: Stan Isaacs’ words are back in print. In his retirement, Stan was writing his memoirs, but after the crushing death of his vibrant wife, Bobbie, in January of 2012, Stan’s heart was broken, and the book was unfinished when he slipped away 15 months later. Fortunately, Aram Goudsouzian, an editor for the University of Illinois Press, became interested in the genre of sportswriters – starting in the late 50s, in their chattery, irreverent, fearless and informed glory in the 1960’s. The Chipmunks: Stan Isaacs. Larry Merchant of the Philadelphia Daily News and Leonard Shecter of the New York Post and a dozen or more chatterers. “I’ve been working on a book about sportswriters and the big political and cultural shifts of the 1960s, and in the course of my research I read Mitchell Nathanson’s excellent biography, Bouton,” Goudsouzian wrote in an e-mail. “In the notes he had a record of Stan’s unpublished memoir, which I thought might be a good primary source for my own book. So I emailed Nathanson about it, and he put me in touch with Stan’s daughter Ellen, who sent me an electronic copy. As I read it, I had the sense that it should be published – though it needed editing, it had Stan’s distinctive voice and a lens into the shifts of the Chipmunks’ era.” Never having met Stan, Goudsouzian gave the manuscript some nips and tucks, and undoubtedly some enlightened surgery to highlight the inner Isaacs. Stan knew himself as a quirky lefty, coming out of the Depression and the politics of the 1930s, and he tells his best stories in this book. The photo on the cover? One night, covering the Yankees in the old ballpark in Kansas City, Stan chose to watch the game from the hill behind right field, patrolled by a few sheep. Vintage, definitive Stan Isaacs. They were wonderful days -- and I carried them with me to the Times in 1968, blessed with the skills and attitude of Isaacs and Jacobson and the other Chipmunks. I am extremely proud of my career at The Times, but like ball players who have loyalty to more than one ball club, I still refer to both Newsday and the Times as "we." Jacobson’s world, Isaacs’ world, are definitely from another time. Nowadays, young people do not read newspapers…and newspapers die….and even a great paper like The New York Times has chosen to blow up its sports section, with its tradition of reporters and columnists licensed to report and comment. Miraculously, in these hard times for sports sections, Stan Isaacs still patrols left field and Steve Jacobson still carries Jackie’s torch. Together again. In its time, it was eagerly awaited at mailboxes, week after week, for the words and pictures by masters.

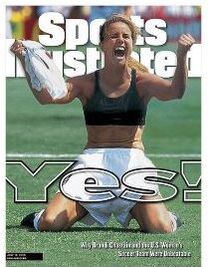

Kids don’t read today, which means the average age for readers of print news is probably in the 50s, heading toward the 60s. That’s the best way I can explain the rot that has struck Sports Illustrated. There’s no money in it – certainly not for the speculator-gravediggers who make money by investing in once-great papers and magazines and then writing if off on their taxes. Rich people know how to do that. But once upon a time, Sports Illustrated arrived mid-week, and was a legitimate excuse to spend an hour or three reading it. I started out by reading Robert Creamer on baseball and Dan Jenkins on football and then in my working time I never knew where Gary Smith or Frank Deford had been – mainstream or oddity sport. Whatever the subject, it read better in SI. And the photos. As a working scribe, I ran into the masters like Walter Iooss, Jr., Heinz Kluetmeier or Neil Leifer, deservedly full of themselves. SI also hired the best free-lancers and paid them well. Now a few photography empires have cornered the market – even buying up the photo files of fading empires like SI. My friend John McDermott has watched the fading of the magazine free-lance market for photographers. From his home in Italy, he shared his memories of the golden days of magazines – Newsweek, SI, and others. “I worked for SI a lot. It was soccer that got me in the door initially. I had a meager portfolio and somehow got an appointment to see a photo editor. I think they didn’t know anyone who shot soccer so they gave me a chance. First job was to shoot England v. Italy at Yankee Stadium in 1976 during the Bicentennial Cup. I don’t think I did very well, but maybe they just didn’t know the difference. “I started to get more work for them, and on other things, mainly ‘personality pieces,’ the lengthy back-of-the book stories focused on an athlete. I did Dwight Clark, Matt Biondi, shotputter Maren Seidler, Stanford tennis program and coaches, basketball player Chris Webber and others. More soccer including NASL championships, the Cosmos, Pele’s Farewell Game, Beckenbauer, Maradona’s first game with Argentina in Europe, the 1990 US World Cup team. Pebble Beach golf. “Best assignment ever was a twelve-page essay on rugby where they just told me ‘go and shoot rugby, start with the Monterey Tournament and then figure out what else you can do.’ They sat on it for a year, then during a slow period, a baseball strike, they ran twelve pages, which for SI was a very big deal.” John recalls working with writers like Kenny Moore, Demmie Stathopoulos, Frank Deford, Clive Gammon and Ron Fimrite. Great names, great talents. SI made a newspaper columnist want to check the weekly column in the back of the magazine, to see what Rick Reilly did in his flashy way or what Steve Rushin did in his thoughtful way. A lot of SI writers were good company – friends like Michael Farber on the hockey beat, Grant Wahl on the soccer beat, my neighbor and friend Walter Bingham, Sally Jenkins on the tennis beat. (I now refer to Sally as “the last sports columnist,” meaning she maintains the high level at the Washington Post once demanded at dozens of major papers.) One of my best assignments, ever, was the 1991 Pan-American Games in Cuba – hanging with two SI reporters, Alex Wolff and Merrell Noden. (Our new best friend and interpreter, Ziomara, nicknamed them Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford, as I recall, for their American movie look.) If I had to pick one classic article from Sports Illustrated, it would be William Nack’s farewell to Secretariat, in 1990 – when the greatest horse of all was put down in extreme old age. Bill put his skill and intensity into everything he did, but particularly horse racing. He covered Secretariat’s Triple Crown and he remained in touch into equine old age on the farm in Lexington, Ky. (I got to pet the giant red beast, swaybacked by then – with the help of a few contraband sugar cubes -- during Derby week in 1989.) A year later, Nack got the call from a friend to get himself down to Bluegrass country to say goodbye to Big Red. Knowing how long it took for him to write, I bet he shed many tears while writing his elegant ode to a dear friend. SI had the space, and the color pages, and the freedom for Bill Nack, and so many others, to write what they knew and felt. Then people stopped reading newspapers and magazines. The New York Times blew up its sports section a few months ago, in favor of taking stuff off a website. The great Baltimore Sun has just fallen to scavenger types. This will sound snide, but when I heard investors were preparing to put down Sports Illustrated, I had to catch myself thinking, “You mean, it is still publishing?” In its time, it was a giant. *** Bill Nack’s farewell to Secretariat: https://www.si.com/horse-racing/2015/01/02/pure-heart-william-nack-secretariat A partial list of SI writers. (Not counting the great photographers.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Sports_Illustrated_writers *** Please, recall your favorite SI articles – and favorite SI photo spreads – and include them under “Comments.” GV The Daily Miracle is waiting every morning at the top of the driveway, courtesy of a diligent delivery lady, who never misses a day.

Friend of mine at the New York Times plant in College Point, Queens, calls it “The Daily Miracle,” because it returns every day (with the collaboration of thousands of journalists in Manhattan, in Queens, and all over the world. This bundle in a blue bag is a miracle even though everybody knows young people don’t read newspapers, but there are enough of “us” who want to hold the paper in their hands and flip pages and peruse, peruse, peruse. (The plant also prints 50-odd dailies and weeklies – part of the miracle but also the foresight of the people who run the NYT.) Take this from an octogenarian who must have his fingers on “the paper,” there is another miracle in the journalism world – the ever-changing website of the same New York Times, thousands working around the world in all the continents and all the time zones. As we speak. Nothing like flipping electronic pages in the middle of the day to keep up with the judicial progress against the larcenous and bumptious Trumps. Or waking up and checking what has happened in the Middle East since the cut-throats came across the border to kill and kidnap on Oct. 7. We get the news and the embellishments from a great news-gathering organization (where I used to work), and that is a miracle because it took decades of insight and doubt and trial and error to save the blue-bag Daily Miracle but also to create the alter ego known as nytimes.com. The evolution of newspaper into the journal that never sleeps is documented in a new book, “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism,” written by Adam Nagourney, one of the many great reporters, who is still working there. For 43 years, I knew, I witnessed, I even managed to grumble and whine about the changes being foisted on us. (I do not do change well. I can provide witnesses.) I was around as a news reporter in the ‘70’s, when bulky and balky Harris terminals swallowed entire masterpieces after hours of pecking away at the keyboards, even though we had pushed, poked, whacked the “Save” keys. A living technology pioneer-saint named Howard Angione talked some of us out of our rages. Later there was another saint named Charlie Competello. Meanwhile, our bosses competed in their lairs. Some of them understood the online era at first and some did not. The book goes into Shakespearean length to show the decades of the long knives, over policy, over technology, and over flat-out human emotions. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”—King Henry the Fourth, Part Two, William Shakespeare. Top editors feared the managing editors they had just appointed and even publishers and family had a mix of human strengths and weaknesses. But four decades of friction came and went – and the NYT is in Ukraine and the Middle East and all over the United States. I’m not getting into personalities in this review. I just want to bear witness to the foresight and talent and perseverance of the owners and the editors and the reporters – and the readers. I had the honor of working for national editors Gene Roberts and Dave Jones and the great copy editors on that staff. I remember being assigned to the federal pen in Marion, Ill., where a lifer bank robber had completed his bachelor’s degree in a prison program. I turned in my article and copy editor Tom Wark called me and said, “This is not up to Vecsey standards…could you run this through the machine again?” I tried. The NYT had dozens and dozens of great editors like him. Later I worked for Abe (Rosenthal) and Arthur (Gelb) as a Metro reporter in the 70s. They could forget about you for weeks…but then they could give you an assignment that made you glad to be a journalist. (The end of the Vietnam War, 1973, as seen by cynical veterans in a steamy bar in deepest Queens, my choice of venue.) The computer age was under way when I returned to Sports in the 80s. Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, with his snarky sense of humor, held an occasional lunch meeting with us in Sports. One day I played grumpy-lifer and asked why the NYT needed the color that was starting to appear in the paper. The publisher said, as I recall: “We live in color. We dream in color. The Times needs color.” Look at the great reporting by Amelia Nierenberg and brilliant photos by Hilary Swift on grieving Maine in the past week. Of course, Arthur was right. The book describes how the Times dispatched long-time editor Bernard Gwertzman to bridge the gap between the traditional NYT and the infant Web-era NYT. One day, Gwertzman held a lunch with Sports types ad one of our many great reporters complained about his scoops going on line so early that his good pals on other major papers were poaching his work. Gwertzman was unflappable: “A year from now, we won’t be having this discussion,” he said. He was right. The reporter became a star in the Web age, too. (Recently, the NYT blew up its talented sports section. That decision will undoubtedly be in the next NYT history book.) But for now, Adam Nagourney has given Times readers (and Times lifers) a thorough view of the comings and goings of talented, driven journalists. I am in awe of the lavish meals and copious alcohol consumed by our leaders, often followed by sharp managerial decisions ...placed between career shoulder blades. Nagourney reminds us how long it took for female journalists and gay journalists to get a fair break to use their talents. Good for him. The editors argued and decided and changed courses. But somehow, somehow, The New York Times is better than ever, 24 hours a day. In print. Online. Either way, a daily miracle. ### I have received so many emails and calls since the announcement that the New York Times’ sports section will be closed.

It seems like the best thing to do is try to answer many of them at once – and ask for your own reactions and your memories. From my standpoint, this has been coming on for a long time, since people stopped reading newspapers – a terrible trend for swaths of the country that no longer have the information to cope with government and business and health issues. When I see once-great papers like the Louisville Courier-Journal get Gannetized, my heart breaks. The sports sections were particularly vulnerable. While I was still working, valued colleagues, particularly sports columnists, began to be disappeared, sometimes en masse. Fortunately, The New York Times made a lot of good decisions – a web presence, color in the paper, and more valuable news and information about health and safety and cooking. Perhaps the best business decision was to use the sparkling printing plant in College Point, Queens, to print other newspapers. The Times now prints 60 papers, from dailies to weeklies, news and ethnic. That pays some bills around the paper. Since I retired at the end of 2011, the Times has flourished around the country and around the world, using other print plants. However, deadlines had to conform, with available press time, which ultimately meant the Times had to stop covering games -- Mets games, Yankee games, Giants games, Jets games, etc. To its credit, this great paper continued to report and comment about the major issues in sports – brain concussions, how money was made and spent, gender issues, racial issues. Inevitably, the excitement over the “local” teams was lost. I felt the absence of emotion. Readers felt it. Speaking for myself, in retirement I had more time to read the paper – the print version, in a blue bag, in my driveway every morning. My friends in the Times printing plant call it “the daily miracle,” and for me, it is. In recent days, I have been happy to see stars like Linda Greenhouse writing about John Roberts’ Supreme Court, and Michael Kimmelman writing about New York’s perennial albatross, Penn Station and Madison Square Garden. I love to find the great reports from Dan Barry and I love the wit of Vanessa Friedman, writing about style. The Health section every Tuesday sparked my interest in evolution. But now the sports department is going to be disappeared, while promising new jobs for great editors, great reporters. I hope they appreciate Kurt Streeter, whose most recent Sports of the Times column savaged the pro-gambling baseball commissioner and the owner of the A’s, as they prepare for the A’s to vacate Oakland for Las Vegas. Readers feel there is a hole in their lives. I can tell you about my sense of loss of the Sports Department – once a bustling clubhouse of colleagues, specialists, who schmoozed and kibitzed across their specific skills. They formed a team. The Times claims it will find suitable work in the many departments left. My reporter friends are great journalists, who can do anything -- Joe Drape, Jere Longman, John Branch, Ken Belson, Andrew Keh, and so on. In 2004, at the Summer Olympics in Athens, a demonstration broke out, and Juliet Macur went right toward it, getting tear-gassed but coming back with information. Juliet will be covering the Women’s World Cup of soccer in Australia and New Zealand later this month. She can do anything. So can they all. But something will be lost – particularly the presence in a sports setting of specialists like Tyler Kepner, the baseball columnist, who has been writing since he put out his own newspaper as a young kid in a Philadelphia suburb. I hope they can find a regular spot for his voice as he explains the goofy doings in his chosen sport. Meanwhile, the Times has spent a ton of money on a website, The Athletic, which apparently has people everywhere. I have glanced at The Athletic, and I gather it has a few colleagues of mine who used to work in newspapers. But I want to add that a lot of websites have box scores and opinions and transactions. I will continue to seek out columns by my friend Sally Jenkins in the Washington Post, whom I call “The Last Sports Columnist.” (Did you see her recent masterpiece on Martina and Chris?) For my daily fix of soccer and snark, I will continue to read columnist Barney Ronay and savvy reporters in The Guardian. Local NY sports? Newsday and the Post (even though I try not to ever pay anything to the Murdoch clan.) I am sure the byline stars from Sports will prosper in other parts of the paper. They are familiar with the style marshals, the wise old elephants in the office, who make sure the paper looks and reads professional. I always liked to watch the faces of colleagues in the pressbox as we dickered with the home office over a comma or a semi-colon. I appreciate the nostalgia for the Times sports section. Please feel free to share your opinions, your best memories. I can hardly wait to read the shop talk from Mark Landler, who does such a masterful job as the NYT’s correspondent based in London. Just the mention of coronations always makes me think of the great memoir of Russell Baker, who covered the 1953 ceremony for Queen Elizabeth, for the Baltimore Sun. (see below) Now, a great coronation output by Landler – my teammate during the Times’ coverage of the 2006 World Cup in Germany – on deadline, of the coronation of King Charles III on Saturday. (Landler was joined by a story on Queen Camilla by Megan Specia and a fashion Vanessa Friedman who has trained me to read her fashion essays.) Landler wrote a breaking news story with the lush details any Times reader would want – including, who was that lady in the blue-teal gown, carrying the sword? Why, it was Penny Mordaunt, the leader of the House of Commons – her very presence in the ancient ceremony another sign of inclusivity in not-your-grandparents’ England. Whether “we” should care about royals and coronations is another story. I checked, and my two rellies – Sam from the States and Jen from Australia – were not in their London base but rather in southwest France – and they were most decidedly NOT WATCHING. But I was, and so was the lady next to me, both of us with genes and family names and ancestry that go back to….well, in her case, William the Conqueror. (Me Mum was born in England but was decidedly a Churchill fan, not a royals fan.) Anyway, we gave the royals' production firm good marks for the visible Sikhs and Muslims and Buddhists plus the mention of Ephraim Mirvis, the UK grand rabbi, who was quartered near Westminster Abbey overnight to observe the Sabbath. (One favorite moment was the modern alleluia hymn sung and danced by the Ascension Gospel Choir, gracing the ceremony with their voices and their joy.) All of that was lavishly presented on the tube (anchored by Alex Witt, the weekend pro on MSNBC, with the indispensable Katty Kay back home in London, sending vital posts from a favorable spot on the parade route.) And soon the NYT will surely tell how its staff produced a masterpiece (color photos!) Speaking of shop talk: The landmark for coronation tales has less to do with young Elizabeth than with young Russell Baker, who had been posted in London by the Baltimore Sun, which in 1953 was a major, major American daily, always looking for young talent. Many decades later, as part of his memoirs, ("Growing Up" and "Good Times") Baker wrote about covering the 1953 coronation -- delightful details of how he scouted out a proper outfit for the ceremony, and how he packed a brown-bag lunch with two sandwiches and a few chunks of cheese and a tiny bottle of brandy to fortify himself during the long day. And how his wife, Mimi, was invited to a friend’s house where there was a TV set. Ever since Baker’s coronation tale was published, I consider it one of the inspiring great glimpses of a young journalist, being challenged by a great paper, and obviously succeeding, and how, decades later, Baker could recall the details of that assignment-of-a-lifetime. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/01/01/magazine/brown-bagging-it-to-buckingham.html **** Brown-Bagging It to Buckingham

By Russell Baker Jan. 1, 1989 MY INTENTION WAS TO become a great novelist, not a foreign correspondent, so naturally I never expected to end up in Westminster Abbey covering the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The chain of events that put me there began in 1947. The Baltimore Sun needed a police reporter that year. The managing editor mentioned it to an editorial writer who lectured at Johns Hopkins, and the editorial writer mentioned it to a professor, who mentioned it to me and gave me a phone number to call at The Sun. I was to ask for a Mr. Dorsey. Newspaper work didn't really interest me, but some great novelists had started as newspaper men. Newspaper people could never be much better than hacks. Still, they did write, didn't they? What's more, they got paid every week. I began to feel reality taking residence in my soul. ''What's your experience?'' Mr. Dorsey, The Sun's managing editor, was asking when I came to his office a few days later. ''I've worked on the Johns Hopkins News-Letter.'' ''You realize you can never get rich in the newspaper business,'' Mr. Dorsey said. ''Rich?'' I tried to smile the smile of a man calmly resigned to a life of penury. ''I never expect to make a lot of money.'' Mr. Dorsey sent me away with a handshake and a loud snort. A week later, the phone rang while I was eating supper. ''This is Dorsey. If you still want to work for me, you can start Sunday at $30 a week.'' I was flabbergasted. Thirty dollars a week. That was Depression pay. This was 1947. A pair of shoes cost $9. I'd been in New York a few weeks earlier, and the prices there were incredible. A theater ticket had cost me $1.50, the hotel was $4.50 a night, a sirloin steak restaurant dinner, $3.25. Thirty dollars a week was an insult to a college man. ''I'll take it,'' I replied. A MISFIT AT POLICE REPORTING, after a year on the job I was falling behind at The Sun. New people were being hired, assigned to police coverage for a month or two, then moved inside. ''Moved inside.'' On The Sun, those words meant having your own desk, being sent on fascinating general assignments, and never having to humor a policeman again. Luckily for me, The Sun's famously miserable pay had sent morale so low by 1949 that there was constant personnel turnover. Everybody seemed to be looking for a job with better pay, and many were finding them. This left the paper perpetually short of experienced reporters. As a result, to get ahead you didn't have to be very good, you simply had to hang around. Being unmarried and living at home, I could get by on my Sun salary, which averaged $50 a week in 1949, so I could afford to hang around. By the end of the year, I was making a gaudy $70 a week. This was enough to get married on, if you were young and foolish enough to believe in happy endings, which was precisely how young Mimi and I were. Then there came a miracle. The telephone woke me around 10:30 in the morning. I normally didn't get to bed until 4, so it was still dawn on my personal clock, and I growled a sour hello. THE MARTINIS CAME, THEN THE food and the beer, and when we started to eat, Buck Dorsey said, ''How old are you?'' I said I was 27. ''How would you like to go to London?'' he asked. The question was so preposterous that at first I did not absorb its implication. Well, I said, a little hesitant, we had just had a new baby, and I wasn't sure it was a good time to go off and leave Mimi alone. ''Could I think about it a little while?'' I asked. Buck Dorsey was looking at me very strangely, and as the full weight of his great announcement broke over me, I understood why: He wanted me to go to London. ''I mean, how long would you want me to be away?'' I said. ''Probably two years,'' he said. ''That's the usual assignment for men we put in the London bureau. Of course, once you get there and find a place to live, you'd move your family over with you.'' Then Buck Dorsey was talking about the coming coronation of young Queen Elizabeth, which would be the great story during my time in London, but I was now too excited to pay close attention. I was going to escape the drudgery of the local newsroom, after all. I ROSE AT 4:30 ON CORONATION morning and started dressing in white tie and tails. Heavy rain was beating against the window and it had been raining all night, drenching a million people camped in the streets. What should have been a rosy June morning looked like the start of a wet, black nightmare. I was going to have to walk out into that downpour in fancy dress because I had been too stupid to apply for a permit to take a car to Westminster Abbey. If I had filled out the forms, authoritative windshield stickers would have been issued, and I could have ridden in splendor. But I had laughed at the idea. An absurd fuss, a preposterous waste of car-rental money. Living within a short walk of the Abbey, I could easily stroll up there on a lovely June morning. It wasn't just chintziness that impelled me to walk. The American in me was tickled by the idea of walking to a coronation instead of being chauffeured by a lackey. Thomas Jefferson had walked to the Capitol for his first Inauguration. Let the English see how Americans did these things. Watching the rain outside made me curse my foolishness. That short walk to the Abbey seemed short only because I had never walked it in pouring rain. Actually, it was at least a mile. And in top hat, white tie, tails Instructions had been firm about dress. People not entitled to wear ermine, coronet, full dress uniform, court dress, levee dress coats with white knee breeches, kilt, robes of rank or office or tribal dress must wear white tie and tails, with medals. I didn't have medals. Since I didn't have a dressy suit either, I rented the full rig from Moss Bros., famous among the haberdashery-wise throughout the Empire and always pronounced ''Moss Bross.'' Knowing there would be a coronation run on Moss Brothers, I went early and got a fairly decent fit. Because I'd never worn tails before, I got up a little earlier than necessary against the possibility I might have a breakdown getting into the thing. Mimi fixed a big breakfast. It was going to be a long day. I had to be in position inside the Abbey by 7:30 and wouldn't get out until 4 in the afternoon. The rain let up while we were eating. Mimi got the camera and, while Kathy and Allen watched, took snapshots of Daddy wearing his coronation suit to show their grandchildren. Whatever gods may be, they were with me that day. The rain faded to a weak drizzle, then stopped altogether just when it was time to start for the Abbey. No, I would gamble and leave the raincoat home. Walking to the Abbey in top hat, white tie and tails could be a great gesture only if it were done right. Wrapping up in a dirty raincoat would make it comical. Mimi was going to the house of Gerry Fay, London editor of The Manchester Guardian, to watch the day's events on television. There weren't a lot of television sets in London yet, but Gerry's house had one, and his wife, Alice, had invited several disadvantaged families like mine to come see the show. Because it was a big day for me, as well as for the Queen, I kissed Mimi and the children goodbye, said, ''Wish me luck,'' stepped out into Lower Belgrave Street and headed toward Victoria Station. Not a soul in sight from Eaton Square all the way to Victoria. I strolled briskly along through the heavy, wet air, getting used to the feel of the high silk hat on my head, happy to discover that it was not going to tip and fall off. In my hip pocket I had a half-pint flask of brandy to keep me awake during the long day. In my hand, I carried a brown paper bag containing two sandwiches and three or four chunks of yellow cheese. In my pockets, I had a sheaf of official cards issued by the Earl Marshal, conveying the Queen's command for policemen to pass me safely through all the barricades and instructing me which church entrance to use, how to conduct myself while eating during the ceremony (discreetly), and where to find toilet facilities in the Abbey. Rounding Victoria Station, I heard the hum of a great, damp concentration of humanity. Packed from curb to building line on both sides, all along the five-mile route of the coronation procession, people had spent the rain-soaked night on the sidewalks. How many there were I didn't try to guess. The papers said millions, overstating it a bit, as newspapers usually do when writing of crowds. Still, there were plenty. I had walked among them the night before. They were bedded down in sleeping bags and soggy quilts, under raincoats and makeshift oilskin tents. Many had brought camp stools, portable stoves, knapsacks, picnic baskets, knitting bags, radios. They brewed tea on the sidewalk, they read, they slept, they sang, they sat stoically in the rain with only a felt hat against the downpour, they dozed with heads pillowed against tree trunks and lampposts. During the war, London's ability to ''take it,'' no matter how much punishment the Luftwaffe gave them, became such a cliche that it later turned into a small joke. On this cold, bitter, rainy night, with those good-natured hordes cheerfully camped on rainswept concrete, I had a glimpse of that peculiar British fortitude, dogged and indomitable in the face of adversity, which made them so formidable to Hitler. At the morning's soggy dawn, in my top hat and tails and graced, I hoped, with some of the elegance Fred Astaire brought to the uniform, I presented my credentials to the police guarding the barricades on the route to the Abbey. Miracle of miracles! The police recognized them, passed me through, waved me into the broad empty avenue called Victoria. The avenue ran straight to Westminster Abbey. I prayed I could make it before the skies opened again and stepped out as rapidly as I could without losing dignity before the damp mob staring at me. And, yes, now applauding me. A smattering of applause came off the sidewalks as I strode along. They had been waiting so long for something wonderful to appear. Now here was the first sign that wonders would indeed pass before their eyes this day. I fancied myself a vision for them, a suave, graceful gentleman in top hat, white tie and tails, signaling the start of a momentous event. At that moment, I was the event. The applause grew as I stepped along. Having always prided myself on shyness, modesty and distaste for theatrics, I was surprised to find myself not only enjoying my big moment, but also, here and there, where the applause seemed especially enthusiastic, tipping my silk hat to the audience. It wasn't until I got within a block or two of the Abbey that I understood what was happening. There I noticed a man in the crowd talking to a companion and pointing to my hand holding the brown bag with my lunch. At this, his companion laughed, then applauded vigorously: What delighted the crowd was the spectacle of a toff brown-bagging his lunch to the coronation. By this time, I was certain to reach the Abbey before the downpour resumed. That certainty and the pleasure of strutting a great stage exhilarated me. Triumphantly, I raised my lunch over my head and waved it at the crowd, and was washed with a thunder of cheering and applause that the great Astaire himself might have envied. A moment later, I passed into the Abbey for a long day's work. I HAD A GOOD SEAT IN the Abbey. It was in the north transept looking down from about mezzanine level onto the central ceremonial theater. It provided a clear, unobstructed view of the Queen and the throne in left profile. Opposite, in the south transept, sat the lords and ladies of the realm in scarlet and ermine. The few good seats allotted to American correspondents had been distributed by a lottery drawing, and I had got lucky. After being ushered up the ramp to the chair I was to occupy for the next seven or eight hours, I took a spiral note pad out of my pocket and began taking notes, just as I would have done at a three-alarm fire in Baltimore. This was by design. After worrying for weeks how to cover a coronation, I had decided to cover it pretty much the way I would cover any routine assignment on the local staff. I would show up, keep my eyes open, listen closely and make notes on what I saw and heard. My hope was to produce a story that seemed fresh, and I thought this might be possible if I treated it as though I'd just strolled into the newsroom one afternoon and the city editor had come dancing at me, shouting: ''They're having a coronation up at the Abbey in 10 minutes. Get up there as fast as you can.'' This was not the safe way to cover the coronation, but it offered the best chance of doing a good story. The safe way was to write the story before the coronation was held. This was also the surest way to produce a lifeless story. This idea I discarded quickly. For one thing, I was cocky about my ability to produce a fresh story of several thousand words under deadline pressure. I had always worked well on deadlines, maybe even better than when there was time to dawdle. So I entered the Abbey with no backup story ready to send in case of emergency, took out my spiral pad, and started jotting notes on what I saw. Tier upon tier of dark blue seats edged with gold. The stone walls draped with royal purple and gold. The stained glass of rose windows transforming the gray outer light into streams of red, yellow, green and blue high up against the Abbey roof. Many of these notes appeared almost unchanged. ''Yellow men and tan men, black men and pink men, men with cafe au lait skins and men with the red-veined nose of country squiredom.'' ''Malayans with bands of orange and brown-speckled cloth bound tightly about their hips. . . .'' ''Men dressed as Nelson might have dressed when he was sporting in London . . . like courtiers who dallied with the Restoration beauties of Charles II's court . . . like officers in Cornwallis's army. . . . ''. . . violins far away eerily unreal. . . .'' Writing to my mother later, I disposed of the coronation in a single paragraph: ''I am so sick of the whole business that I can't write about it. Suffice it to say that I was in the Abbey about 7 and didn't get out until 4 P.M. In this time, I ate two sandwiches, several chunks of cheese, went to sleep three times, and drank a half pint of brandy to keep my blood flowing. I was seated in the midst of all the African and Oriental potentates and had a fine view of the staircase leading down to the water closets, where I could see Africans in leopard skins and Chinese dressed like French admirals queuing up to wait their turn to make water. I came out of the Abbey, stiff as a board and woozy, and had to run through a cold driving rainstorm to find a taxicab. Then I had to write for six hours, producing that mass of type which ran in The Sun. I didn't feel that I laid an egg completely, because next day mine was the only story from any American newspaper which had parts reproduced in any of the London papers. Considering that papers like The New York Times and Tribune had 25 and 30 reporters to do the job, I felt we did fairly well.'' The humility in this last sentence was entirely bogus. By the time I wrote my mother, the reaction from Baltimore was in, and I felt I had done far better than fairly well. I felt I had scored an absolute triumph. The day following the coronation, I had a cable signed by 16 members of the city staff. It said: ''Magnificent. Your coverage worthy of the coronation, and of Baker.'' Pete Kumpa, one of the best newsmen on the staff and an old friend whose regular correspondence kept me posted on events in the home office, reported: ''Your story received here in the greatest admiration. Magnificent is the word.'' The greatest ego bloater of all, however, was a note from Buck Dorsey's wife, Becky, marked ''Very Personal.'' She reported various compliments about the coronation piece which Buck had received from various high and mighty types in the Sun hierarchy, then said: ''The nicest of all, Tom O'Neill, said, 'Buck, the boy knows how to use the English language. It's a finished piece, beautifully done.' '' O'Neill was the most dashing reporter on The Sun. Closing, Becky wrote, ''I do not know that Buck would approve of my telling you all this, but on thinking of that fine ignorant old face of yours, I couldn't help myself.'' I could have discounted praise from my friends on the city staff. They had been writing glowing reviews from my very first days in London. They were my cheering section back in Baltimore, and for good reason. Being picked from the local staff for The Sun's plum assignment abroad, I was a symbol of hope for them. If one man from the local staff could escape into the sweet world of foreign correspondence, there might be hope for all. They had a stake in seeing me succeed and wrote constantly, applauding and cheering me on to keep my morale high. Becky's report about Tom O'Neill, however, was not so easily explained away. Nothing could have done more to puff me with self-admiration than those few words about Tom O'Neill's remarks to Buck. I was not the type to have wildest dreams, but if I had been, the wildest I could have concocted would have had Buck Dorsey listening with the respect he always accorded his favorite reporter as the great O'Neill heaped me with praise. Two months after the coronation had crowned me with glory, my triumph was confirmed in a cable from Baltimore: ''Ten dollar merit raise effective next week for you. Happy August Fourth and all that. Love. Dorsey.'' That brought my salary up to $120 a week. I was a $6,240-a-year man. **** Russell Baker is a columnist for The Times. This article was adapted from his book, ''The Good Times,'' to be published by William Morrow & Company in June. (15 MARCH 2023. BEWARE THE IDES OF MARCH.)

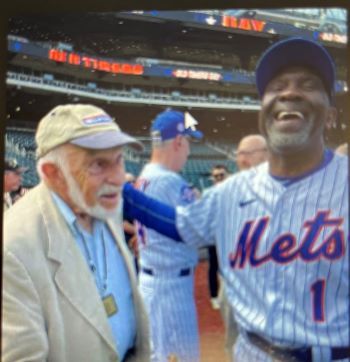

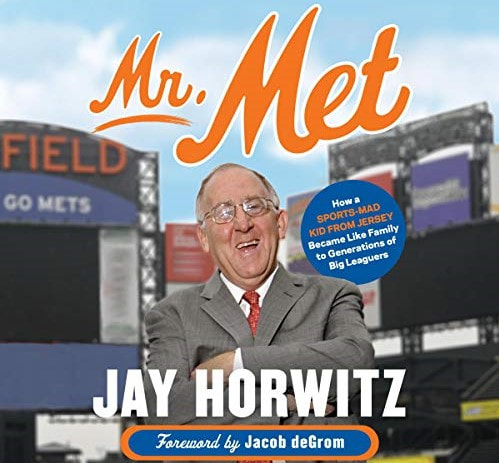

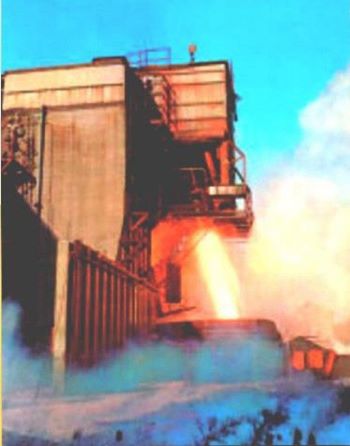

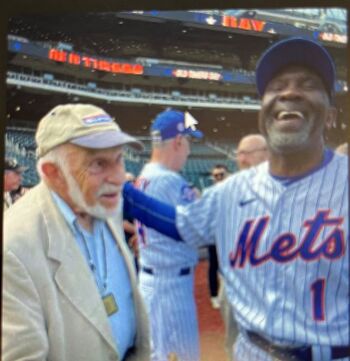

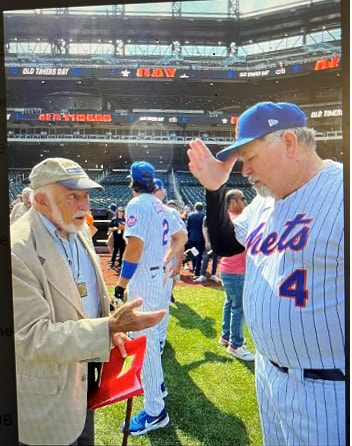

AS OF WEDNESDAY MORNING, I HAVE RENEWED CONTACT WITH THE WEB COMPANY. I'LL TRY TO ADJUST TO NEW CONDITIONS IN NEXT FEW DAYS. THANKS FOR THE NOTES, YOU HARDY FEW WHO NOTICED I HAD BEEN DISAPPEARED. TO BE CONTINUED. MAYBE. IT IS, AFTER ALL, THE IDES OF MARCH. GV Rupert Murdoch's star agitator, Tucker Carlson, is sharing the secrets of his squirrelly heart, via internal e-mail. He says he hates Donald Trump, as opposed to the slavish adoration he shows on Fox Fables. How to explain this? Your explanation is welcome on Comments. (below) Meanwhile, Alex Murdaugh is locked up, permanently. Rupert Murdoch may be out a billion dollars or more for emitting falsities about the Dominion company and called it "journalism," when he actually admits they are lies. I was wondering about the two blokes with similar names a couple of weeks ago, wondering if they are related, so I looked it up. “Originally, the name was a nickname for a person associated with the sea,” says the website, House of Names. The name Murdoch derives from one of two Gaelic names which have become indistinguishable from each other. The first of these, Muireach, means belonging to the sea or a mariner. The second name is Murchadh, which means “sea warrior.” As for the other man in the news: The name “Murdaugh” is “an altered form of Murdoch,” according to “The Dictionary of American Family Names.” I do not mean to make light of the terrible events in South Carolina that sent Alex Murdaugh, a so-called scion of an old family off to prison in handcuffs, convicted of the murders of his wife and younger son. And there are other deaths in the backdrop, including a Murdaugh family housekeeper who died, perhaps from falling downstairs, or perhaps not. (At the very least, the scion stole her insurance money.) That is a tale of privilege and money and also the contemporary usage of drugs. I wouldn’t have minded seeing an occasional mention of the family that profited from OxyContin (and the doctors and pharmacists and flat-out criminals who doled them out like candy, hooking thousands of poor people as well as a lawyer and “scion” with too many toys in lowland South Carolina.) We are left with the image of a wife apparently on the verge of separation, and one son (“the little detective”) discovering more piles of OxyContin, both murdered, and the older son sitting in court, thinking, what? Also in the news is the similarly-named Murdoch, Rupert, who has been infecting public discourse going back to his origins in Australia. He brought his sniggering style of “journalism” to Great Britain and then to the United States. I still remember when a quirky liberal tabloid, the New York Post, morphed into a Murdoch property in the 1970s. Soon we were treated to the Page Six gossip of a lightweight real-estate poseur who would brag about the women he had slept with, allegedly. For many, that was the first time they ever heard the name “Trump.” So we have Rupert Murdoch to thank for that. Recently, in the manner of ganglords, Rupert Murdoch turned on Donald Trump when he began losing at the polls. A Post headline referred to “Trumpty-Dumpty” after recent congressional elections. However, Fox television continued to make money from blather by its commentators – most scandalously in the wake of Jan. 6, 2021, when Trump’s legion of thugs attacked the Capitol. The most famous names on Fox – I cannot even type their names, and of course I never, ever, watch them – stuck with their on-air position that Jan. 6 was a picnic for gentle tourists. In their spare time, however, these paragons of Fox journalism ridiculed some of the buffoon lawyers supporting Trump, and they acknowledged that Trump did lose the 2020 election. But tell that to their viewers out there? People like Tucker Carlson worried about the company profits. “They endorsed,” Mr. Murdoch said under oath in response to direct questions about the Fox hosts Sean Hannity, Jeanine Pirro, Lou Dobbs and Maria Bartiromo, in a $1.6-billion defamation lawsuit by Dominion Voting Systems, the New York Times reported. “I would have liked us to be stronger in denouncing it in hindsight,” he added, while also disclosing that he was always dubious of Mr. Trump’s claims of widespread voter fraud. Now he tells us. Rupert Murdoch has testified that he knew his stars really did not believe the lies they were spewing on-air. He sounds a bit dazed from recognizing reality. But his words are out there. Rupert Murdoch does not believe what makes him rich. So much for journalism. Alex Murdaugh has been sentenced to two life terms. He’s yesterday’s news, sad and horrible news. Rupert Murdoch created a media empire that disregards truth – a television network that helped send thousands of thugs climbing into the American capitol building. Rupert Murdoch undermined a nation, leading to a Gaetz-Greene-McCarthy infestation in Congress. (Can he be deported?) Now his empire is being sued. Apparently, over half the Fox stock is owned outside the Murdoch dynasty. If Murdoch’s acknowledgements ultimately hurt the product -- bad ratings = defections by sponsors – the Murdoch dynasty could be in trouble. Your comments about the strange psycho-drama with Carlson and Trump, and the bizarre hiccups of reality from Rupert. Under "Comments:" In his final hours, Grant Wahl wrote that he had been wrong. He had predicted that the Croatian star Luka Modric was too old at 37 to take the team any further, but after Croatia reached the semifinals on Friday, Grant wrote a mea culpa. Then he went on to write about the second World Cup quarterfinal of the day, and he died, at 48. The circumstances must be examined by American authorities. It’s way too easy for Elon Musk’s new toy to carry kneejerk claims that Grant Wahl was given the Khashoggi treatment, some kind of chemical bonesaw. But we don’t know, not yet. The New York Times and other responsible news agencies quickly examined Grant’s own recent articles mentioning his not feeling well in Qatar, and going to a clinic at the stadium, and he described how other journalists covering this marathon had the same symptoms, from long hours and work stress and crowded press rooms and Lord-knows what kind of travelling microbes. I’ve been there, done that, under the same conditions, during World Cups and other mass events. (More on that, below.)  Grant Wahl was one of the major journalists covering soccer, and had been right about so much, including the repressive air to this World Cup in Qatar, born from scandal – packets of $100 bills to delegates -- in the world soccer body, FIFA. One day at the World Cup, Grant wore a rainbow t-shirt, the universal symbol of support for gay rights, gay existence, and he was held by stadium police, until released. That takes courage. Most people learned after Grant’s death that the rainbow t-shirt was a tribute to his brother, Eric, who is gay. His brother linked the death to Grant’s speaking up for gays, and for thousands of itinerant laborers who have died building these pop-up stadiums in a country with enough money to buy FIFA, the most corrupt sports organization in the world. “They just don’t care,” Grant wrote about leaders of Qatar and FIFA. I read Grant’s posts from Qatar, on the personal website he was building after leaving Sports Illustrated during the ongoing pandemic. He was offering his experience and courage for paid subscriptions, but also made some free essays available. He was no home-bound typist – known as an Underwear Guy -- pecking away on a laptop. Grant Wahl was out there, fully credentialed, with the respect of the soccer community, and also with the eyes of the Qatar security force on him. In a very real sense, he was a lone wolf, existing on his own guts, his own instincts, his own strength, in a FIFA/Qatar environment that had no reason to like what he was typing. As soon as I heard about Grant’s death, I had a pang of déjà vu. I was also 48 during the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, a country I love, traveling to modern and hospitable cities, hundreds of miles apart. I stubbornly continued to jog at high altitude, taking in the bad air. After a few weeks, I was shot. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t move. Couldn’t think. Couldn’t type. Fortunately, my wife was with me, to witness that I was running down. I also had something Grant Wahl did not have these days – a home office. I called the NYT sports department and said I was dragging, and needed a day or three off, but my editors, my friends, Joe Vecchione and Lawrie Mifflin, agreed that I had another great assignment, the Goodwill Games in Moscow, coming up, and I needed to be strong for that. My editors told me to come home, see my doctor, and determine if I was strong enough to go back out to Moscow – which I was. One of the best assignments I’ve ever had. (Plus, my wife was with me, buying fresh vegetables and fruit at a farmer’s market in a nearby square.) I also had editors watching my back, whether as a news reporter or a sports columnist. To this day, even as a typist for my own Little Therapy Website, I consider every word, every opinion, from the vantage point of the great editors, who found mistakes, even reined me in sometimes, much as I griped. Journalism has its dangers. I’ve been sent to riots and shootouts and assassinations and coal-mine disasters where I had to be quick on my feet, but nothing like colleagues currently in brave, admirable Ukraine. Sometimes, “even in sports,” the hours, the travel, the diet, the microbes in crowds, can beat you down. We will learn more. What we know now is that Grant Wahl was doing his work, writing so well about a subject he loved, and he has passed, way too young.  (Laura Vecsey was a terrific news reporter in upstate New York even before she became a sports columnist. She liked to tell me about the stuff a town clerk told her, or a farmer knew. She is revisiting her old reporting grounds as part of her new site, "You Know What I Mean?" ) By Laura Vecsey A Whole World In Your Own Backyard The Town of Malta seems a pretty boring place, until ... LAURA VECSEY The world, we all pretty much know, is a big place. Lots of continents, hundreds of countries, seas and oceans, mountains and deserts, billions of people. The enormity of the world makes it exotic — a feast too big to eat even for the most insatiable explorers and travelers. So why then I am talking about Malta, a nondescript town on a sandy patch of land in upstate New York’s Saratoga County? Ask my friend Lisa Smith. Last week, from her Japanese-Zen influenced home that fronts Willapa Bay in serene Seaside, Washington, Lisa Smith read a post I had written here about buying your first home. It was there, buried in the comments section, that the ever-curious Lisa Smith noted that my spouse, Diane, noted that the first home she ever bought more than 35 years ago was a townhouse in Malta. Malta! If that name stirs any sense of excitement, maybe it’s because the town of Malta carries the same name as the country of Malta, that archipelago between “Sicily and the North African coast — a nation known for historic sites related to a succession of rulers including the Romans, Moors, Knights of Saint John, French and British.” That Malta, set in shimmering green-blue waters, does conjure centuries of world history and human migration. So the name “Malta” rightfully triggers the imagination, especially for curious people like Lisa Smith, an inveterate world traveler who lived in Abu Dhabi and scaled an NYU program there. Lisa has also toured India, graduated from Harvard, ran public TV radio and stations in Seattle and Oregon. She’s also been long paired with the award-winning journalist and book writer Buzz Bissinger. In other words, Lisa Smith has a nose for stories, as much as she possesses a delicious little streak of sarcasm. So what was I to make of Lisa Smith’s quip about the apparently insignificant town of Malta? More important, what was I going to do about Lisa’s pithy remark? I decided that I would take it as an invitation. The Saratoga County, New York town of Malta, it turns out that, is just like all other places in the world: Just another name on a map and yet also a place where there’s a lot more than meets the eye. In fact, the seemingly nondescript town of Malta can make the case that any named place on Earth is its own world. Even more strange, it’s one of the places that taught me, as a newspaper reporter and writer, to look harder and longer and you’ll be surprised what you find. In addition to Malta being the town where Diane bought her first home, Malta was a town I covered for the Albany Times Union. In the late 1980’s, Malta was a part of my news beat in Saratoga County. My job to know what was going on there, and to dig out stories, and to monitor Malta’s local government. This is a townhouse in Malta’s Luther Forest just like Diane first bought. For me, covering Malta served as a primer on how America planned, regulated and protected its citizens and natural resources. I saw how conventional and orderly local governmental bodies carried out their duties. How town budgets were negotiated and passed. How water quality, fire station grants, street plowing and extensions were managed. In Malta, I saw how developers had to demonstrate the impact new housing developments would have; how commercial development was cautiously promoted, how senior citizens would get access to services. And based on what I heard about in the town board meetings, I’d go out and explore for further background or news feature stories that the Times Union would run to show how suburban America was being built out. That included writing about Luther Forest, a section of Malta that was the site for a new housing development where Diane — who I didn’t know at the time — had bought her first house! In 1945, rocket testing was done at the Malta site hidden deep in Luther Forest. The Luther Forest housing development was a planned community, which meant it had a homeowner’s association and a general manager to keep the place running tip top. The manager’s name was Barney Granger, a lanky and taciturn man I spent a lot of time trying to chase down for information or a quote. It wasn’t easy. Barney Granger was always hellbent on riding away from me in a golf cart or his green Ford Ranger pickup. But this quirky memory of Barney Granger in his Ford Ranger is just a little sliver of the real story of Luther Forest. Like a lot of places that seem to have no true personality or any easily identifiable points of interest, Malta’s Luther Forest is riddled with intrigue — not that you could easily tell without doing a little digging, or sky gazing. But the acres of towering pine trees, and the fenced-off areas that warned about criminal trespassing, were a clue. It turns out that the “boring little town of Malta” is actually a nexus of American history from World War II to the Baby Boom era of suburban sprawl to today’s Tech Age of semiconductors and massive retail warehouses. The center of the Malta story is how the 7,000 acres of pine forest started in 1898 by a man named Thomas C. Luther turned into a rocket test site for the U.S. government in the 1940s, after Luther gave some of the land to the U.S. government to serve as a site to test rockets and rocket fuel. That’s when things got really interesting. After WWII, the U.S. started a secret military intelligence program called Operation Paperclip in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from Germany to the United States. That included Wernher von Braun and his V-2 rocket team, plus former members, and some were former leaders, of the Nazi Party. The goal of the Operation Paperclip was to gain military advantage during the Cold War and during the Space Race. In 1945, Luther Forest became the home of the Hermes Project Rocket Test site. Von Braun’s team and 400 General Electric scientists worked at the Malta Rocket Test Station to help the U.S government improve upon Germany's expertise in missiles. That lasted until the 1960. Von Braun, who eventually became the director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and was the chief architect of the super-booster that launched American astronauts to the moon, came to Malta for weeks at a time. When he came to Malta, locals were said to hear the ground rumble and smoke plumes filled the air. It’s said that Von Braun enjoyed his time in Malta, because Luther Forest reminded him of Bavaria. In the 30+ years since I first covered Malta and learned about Operation Paperclip, Malta has further enhanced its standing as the nondescript little town where big things happen. Chip manufacturer Global Foundries’ 1,400-acre campus in Malta, New York. The Luther Forest Technology Campus is a $3.5 billion development that spans 1,400 acres. It is home to Global Foundries, a multinational semiconductor contract manufacturing and design company incorporated in the Cayman Islands and headquartered in Malta. “The company manufactures silicon chips designed for markets such as mobility, automotive, computing and wired connectivity, consumer internet of things (IoT) and industrial.” Global Foundries has brought hundreds of jobs and boosted the development of more suburban housing in Saratoga County. It’s also opened the doors for Amazon to propose a new million-square-foot warehouse on 235 acres south of the Global Foundries headquarters. That plan for an Amazon warehouse was scrapped this year, but not before the little town of Malta and its local planning board had once again flexed its muscle against the big boys from a multi-national company. In other words. Malta? There must be a story there. Right, Lisa Smith? Here’s a photo of the curious Lisa Smith reading in her beautiful home on the coast of Washington State. It was taken by the Daily Astorian (Oregon) newspaper for a story about how people were coping during the pandemic. If you liked this post from You Know What I Mean?, why not share it? Share Photos Galore online: https://lauravecsey.substack.com/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email Not all the old-timers wore uniforms at the grand celebration of antiquity. The old players, legends all, visited Queens on Saturday as the tradition of Old-Timers’ Day was honored after a gaping absence of 28 years. How wonderful it was to sit in my home cave and watch Frank Thomas, Jay Hook, Ken McKenzie and Craig Anderson from the first team in1962. They were good people then, helping Casey Stengel create the lovable myth of the Amazin’ Mets. Now, in the very young and very promising era of the new owner, Steven Cohen, the Mets brought back 60 old-timers to stand in for the Richie Ashburns and Alvin Jacksons who toiled so honorably in 1962. Wonderful touch: room on the field for family members representing Gil Hodges, Tommie Agee, Willie Mays and my departed friend, 1986 coach, Bill Robinson.  Steve Jacobson and Mookie Wilson Steve Jacobson and Mookie Wilson Mingling with the old-timers was my friend Steve Jacobson who helped cover the first season for Newsday and starred as columnist for decades. Steve, going on 89, was welcomed by Jay Horwitz, the haimish maestro of Mets alumni affairs, who also invited me as a surviving veteran of 1962. But I’m still ducking public gatherings during the pandemic, so I stayed home and waited for Steve to call me with the gossip. Steve said he wished he could have chatted with all of them, but there was such a crush, everywhere. He could have talked to Frank Thomas about hitting 34 homers and driving in 94 runs, and Ken McKenzie, who had the only winning record (5-4), and Craig Anderson, who won both ends of a May doubleheader over the Milwaukee Braves to raise the Mets’ record to 12-19 and cause manager Bobby Bragan to call the Polo Grounds a “chamber of horrors.” Oh, yeah. The Mets promptly lost 17 straight, en route to a 40-120 record. Steve also could have talked to Jay Hook, with his engineering degree, who won a game one day and told the writers it was like eating sour cherries but then tasting a sweet cherry. (All three 1962 pitchers present Saturday were part of Casey’s respected “University Men” – McKenzie from Yale, Anderson from Lehigh and Hook from Northwestern.)  Steve Jacobson and Ron Swoboda Steve Jacobson and Ron Swoboda Steve did have time to mingle on the field, wearing a Newsday ball cap, with his wife, Anita, snapping photos of him with epic Mets including Ron Swoboda and Mookie Wilson (who later would gambol in the outfield in the old-timers’ game, along with another sleek alum, Endy Chavez.) The part that Steve treasured most was having a few old Mets tell him he had been one of those sportswriters who did not throw them under the bus when they had a bad hour on the field. We were reporters, we were critics, but we were not rippers. Now the Mets are in a new era. Steven Cohen, a grown-up Mets fan, used his money to hire Billy Eppler, Buck Showalter, Francisco Lindor and Max Scherzer. Who knows if the Mets will hold off the Braves and go far in the post-season? But gestures like the recent Keith Hernandez number-retirement and Willie Mays number retirement (honoring the jolly first owner, Joan Whitney Payson, indicate a generosity of pocketbook and heart. (Speaking of not throwing people under the bus: a few old players and writers and fans have blasted the previous ownership of Fred Wilpon and Saul Katz for not putting enough money into the franchise. I have a friend who ran a center called Abilities, Inc., on Long Island, which helps people function better in work and social life. I am told that the Wilpon-Katz family was generous with money and energy.)

Let's just say: the Mets are in a new era. I was happy to hear my friend Steve Jacobson bubble about his hours back at the ball park with similarly elderly Mets who once upon a time gave the fans so many memories -- some of them even good. The other day I was writing about Dominic DiSaia, and his photo of Vin Scully, and I mentioned photographers I ran around with, back in the day. One of them is John McDermott, who bonded with me on the soccer beat and also at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Norway. Speaking Italian fluently, John charmed our way into the Italian hospitality tent up on an icy mountain plateau, by offering some of my NYT souvenir pins (“distintivi”) -- pure gold at the Olympics. The food was great, as one might expect, and so was the scene when Alberto Tomba, three-time Olympic gold medal ski racer, slowly checked out every table, like an entitled don in one of the Coppola masterpieces. (Oh, yes, that was Roberto Baggio's voice on John’s cellphone.) John McDermott – originally from Philadelphia -- gets around; he loved San Francisco for decades, riding his bike and hanging around with locals like Dusty Baker, but six years ago he moved to Italy with his wife, Claudia Brose, originally from Cologne. They live in Appiano, in the northeast corner of Italy, where German and Italian intermingle, but lately the couple has been making forays to Naples for the ambiance. Claudia has a business conducting photography seminars, and John demonstrates the art of street photography in one of the most vital cities on earth. In Naples – Napoli --- English or northern RAI broadcast Italian only go so far, but in Napule life is often conducted in Neapolitan, not so much a dialect of Italian as a Romance language, endangered, to be sure, descended from Latin. John enclosed a link to a video he put together, using his photographs, backed up by the song by Pino Daniele raised in the Spaccanapoli district, who died in 2015. What draws John and Claudia back to Naples? "The warmth, energy and openness of the people, the chaos and the way everything just works out," John wrote the other day. I get it. My first foray to Naples was in 1970 when my wife and I took our three young children around Italy, the most child-friendly country I know. I went back in 1989 to work on a Times magazine feature on Diego Maradona, the Argentina soccer star who played for the Napoli club – a perfect spot for the flawed athlete. Maradona defied the club’s attempt to set up an interview, even when the club driver took my to Maradona’s villa at the top of the old Greek hill area, Posillipo. I called the number I had for him and somebody messed with my mind, leaping from Spanish to Italian and back. And when I went to a club practice Maradona did not show up that day, leaving his coach sputtering and fuming. Tough town. I realized this at the Napoli club match that Sunday. As I made my way to the press tribune, my guide nudged me under the overhang – just before a wadded cannonball of wet tissue splatted against the wall, like a baseball, where I had been standing. The “ultras” in the stands surely had good aim. Next time I visited Naples was at the 1990 World Cup when Argentina was defending its 1986 title. While I was working, my wife meandered down to the harbor, with life pulsing in the shops – at least until a couple of older ladies wagged index fingers and warned, “Signora, Signora,” and motioned for her to hide the bracelet on her wrist. The local lads were quite adept at snatching jewelry from tourists, they signalled. The pre-teens of Naples are known as “scugnizzi” – urchins – a matter of civic pride. Sit at an outdoor café and a scugnizzo will try to sell a few loose cigarettes, as a way of getting closer. Oh, yes, tough town. Maradona, local hero, played to the Napolitani by urging them to root for his Argentina team when it played Italy in the semifinal. His words, as John McDermott recalls them, were, “364 days a year they call you “terroni” -- an Italian pejorative term for southerners. “Today they want you to be Italian. Don’t be fooled by them. We are your team! You belong with us!” Maradona’s brazen appeal was rewarded with a victory over Italy, but Argentina lost the final to West Germany. He’s gone, now, a victim of his excesses, but Diego Armando Maradona is the flawed patron saint of Naples. As John and Claudia wander through the tangled, pungent streets, they see his likeness everywhere -- the man who found his spiritual home.  “It’s dirty and chaotic and sometimes nerve-wracking,” McDermott wrote me. “But it is also a constant, vibrant, non-stop show of real life lived out in public.”

John expands on his love for Naples in this link: https://aphotoeditor.com/2022/04/14/the-art-of-the-personal-project-john-mcdermott-2/ As I work my way through John’s photos, I can hear, can smell, and surely can see the pulsing life in the alleyways of Naples. *** Long live the photographers who take us to these places. *** The NYT – the former gray lady – now lavishes color photos on its subscribers. Did you see this recent masterpiece on Budapest? https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/15/travel/budapest-hungary-memories.html In the midnight hour on a murky Saturday night in late October of 1986, Shea Stadium was going mad.

A squiggly grounder by Mookie Wilson had somehow kept the Red Sox from winning the World Series that night – and fans were screaming, and nearly a dozen New York Times writers were pounding away at their laptops, shouting into phones, bustling noisily to update their early stories for the last print deadline of the evening. Enlightened cacophony. The sports editor, Joseph J. Vecchione, sitting behind us in the pressbox, was coordinating with the staff in the office, making dozens of decisions, on the spot. Then it was over. We had gotten it done, on deadline. A young Times news reporter, doing spot duty to cover fan madness, police activity, etc., watched the sportswriters (so often maligned as “the toy department”) do their jobs. When things quieted down, the young reporter said casually to the sports editor, “Wow, that was impressive,” or words to that effect. And Joe Vecchione said drily: “We do it every day.” If Joe had added, “Kid,” he would have sounded just like Clint Eastwood in “The Unforgiven.” That professional pride epitomized Joe Vecchione, my friend and advisor in my early days of writing the sports column. Joe passed Friday evening at 85, after years of suffering from Lewy body disease, cared for by his wife, Elizabeth, a wise and devoted nurse. They are parents of Elissa Vecchione Scott and Andrea Vecchione, with three grandchildren: Joe’s aura of family man was clear to people around him. He was a boss with values. I got to know him as a terse, decisive voice on the phone, in the 70’s, when he was an editor in the photo department, and I was a news reporter. Sometimes I was at breaking news and I had to coordinate with the photo editors. Joe was authoritative and efficient. Then he was plucked by Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Gelb to help form the new SportsMonday section, and he was there in 1980 when sports editor LeAnne Schreiber recruited me to be a reporter, filling in for Red Smith or Dave Anderson here and there. When LeAnne moved on, Joe became sports editor, and when Smith died in 1982, it was Abe Rosenthal’s decision to hire a new columnist, and it turned out to be me. Here is where the kindness and shrewdness of Joe Vecchione took over. I had been conditioned by 10 years as a Times news reporter, to keep any trace of myself out of the copy. Give sources. Quote authorities. No opinions. That was the old, gray NYT – and I was one of the foot soldiers, thoroughly indoctrinated. As a columnist, I knew the subject matter, and could write and report, but I was trying too hard to find a voice, hinting at my opinions. I was being too cute. Joe had some advice (and I paraphrase:) “Be yourself. Tell us what you think. People want to know how you feel, what you know, what is right and wrong. Don’t hold back. This is the way things are going these days. You have freedom.” He removed a decade of thoroughly valid reportorial rules, freeing me up to be a columnist. Joe also had an instinct for hiring and enabling good people, hiring columnists Ira Berkow and Bill Rhoden, relying on deputy editors like Bill Brink and Lawrie Mifflin, and he backed up his columnists. I benefited from this in 1990, when I was writing columns from the World Cup of soccer, held in Italy. The young American team, in its first appearance in 40 years, managed a taut 1-0 loss to the Italian team – a huge accomplishment. But I pointed out that Italy did not have great strikers – that is, players gaited to score goals from up close – and I wrote this was because their great national league imported scorers from Germany and Argentina and Brazil. I wrote: “The home-grown players do not develop the knack of scoring. Mussolini once lamented that his was a nation of waiters. It is not stretching the truth to say that Italy is currently a nation of midfielders.” The next day, the sports department got a call from an Italian-American reader who felt using the remark attributed to Mussolini was prejudicial. (Fact is, I love Italy and root for the Azzurri, except when they play the U.S.) The person in the office, taking the call, told the reader that the sports editor was okay with my comment. And who is the sports editor? “Joseph J. Vecchione.” That pretty much ended the conversation. Joe could be tough, and he had to make a lot of decisions. I once was whining in the office about something or other, and Lawrie Mifflin, the deputy sports editor and loyal friend of Joe’s and mine, told me, in effect, “You have no idea how much he has to handle every day” – including complaints from leagues, teams, player unions, sponsors, agents, public officials, fans, to say nothing of staff members. In Joe’s regime, we let it fly, and Joe fielded the complaints, kept most of it from our ears. Joe was sports editor for a decade, then moved back into the mainstream of the paper. He retired at 65 and the editors promptly brought him back to help the transition to the new building a few blocks away. Over the years, I was impressed by the masthead names, the serious people (some of whom condescended to sports personnel), who were his social friends. They trusted him – for core values, like honesty, like thoughtfulness, like culture. That is no small statement about a Times official, my friend, who helped move the sports department into the future. (Any insights/anecdotes about Joe? Please add them in Comments, below.) It all came back to me – my telephone interview with the popinjay proprietor of a doomed gambling den.