|

However she did it, Naomi Osaka found a way to catch the attention of all the people around her.

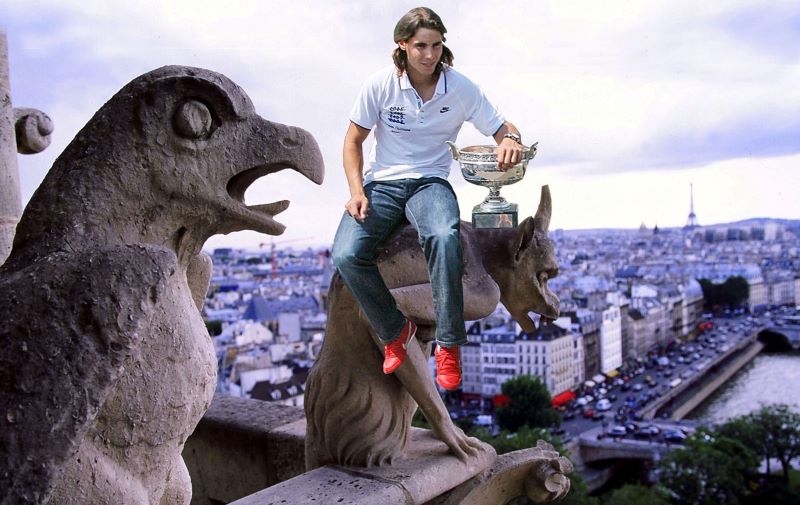

She dropped out of the French Open Monday, saying she has been suffering from depression since 2018. Whatever the circumstances, however she did it, she now gets better help, I hope. Osaka rang the alarm by saying she didn't want to talk to the media, but now it is clear this is much more than a tantrum by a young adult. My one question now is: who knew about her trouble? Who let it get this far? Did she have a worldwide number for a qualified counselor who knew her, who was reachable 24 hours a day? One more thing: Tennis -- with a capital T -- is also to blame. I once knew a doctor who was appalled at the lack of consistent care these great athletes receive. Nothing was available for the next doc-on-call in the next continent to make a diagnosis. Maybe it's better now. But there Naomi Osaka was, in yet another great setting, in yet another Slam tournament, needing to shut it down. Everybody's meal ticket. Did her parents know? Her coach? Her agent? Her hitting partner? Her physio? I am way out of tennis these days and know nothing of her and her "entourage." But she had to draw the line somewhere, and the media is a fine target, I don't blame her. The tennis writers and commentators I know would be the first to say: brave lady, get some help, then come back. If you can. If you want. Be safe. * * * Here is Matthew Futterman's breaking news story from Paris: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/sports/tennis/naomi-osaka-quits-the-french-open-after-news-conference-dispute.html?searchResultPosition=2 * * * (The following is my earlier piece.) How much is it worth to not speak to the scurrilous wretches known as tennis writers? It is refreshing to know that professional tennis pays so well that Naomi Osaka can willingly pay $15,000 to avoid one short session with the assassins and cut-throats of the press. This was the going rate when Osaka ducked the media after her first round at the French Open on Sunday. She had promised not to speak, citing the threat to “mental health” from exposure to the troublemakers with pens and recording machines. Up to now, Osaka has been known for becoming the best female player in the world and also becoming the highest paid female athlete in history, making $34.7-million dollars last year, according to Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kurtbadenhausen/2020/05/22/naomi-osaka-is-the-highest-paid-female-athlete-ever-topping-serena-williams/?sh=3a174251fd33 As the daughter of a Haitian father and Japanese mother, representing Japan and growing up in the United States, she has worldwide appeal, and has often spoken out maturely on gender and racial issues. But suddenly, at 23, apparently on her own, she issued a manifesto that she would not appear at the mandatory conferences after every match. Having covered these post-match conferences since I was younger than Osaka is now, I can attest to the rambling and scattershot tone of these sessions. Most of the accredited media members are from the tennis press – they know the sport, they are solicitous of the players, asking questions about on-court strategy, questionable officiating, luck of the bounce, and upcoming tournament plans. (“Will you be playing at Indian Wells this season?”) Of course, there are also outliers – columnists, news reporters, and nowadays people representing websites and electronic media, looking for a snippet of quote or tantrum or tears. Over the years, I have seen most of the enduring players adjust to sudden swerves of questions just as they adjust to swirling winds or glaring sunlight or capricious surfaces. Nobody gets to major tournaments without learning to cope. Serena Williams deflects questions and criticisms with a combative mode. Her older sister Venus Williams does it with a distant manner; she doesn’t really know anything about this or that. But when they want, both are mature activists for themselves and good causes. Many of the enfants terribles had their own defense mechanisms – John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors ramped up their obnoxious level, Andre Agassi retreated into a “whut?” response, Ivan Lendl could get haughty. Guys being guys. It got them through. The best female players were even younger when they came along, facing questions that often veered into personal issues. Some of the female prodigies seemed preternaturally poised – Chris Evert, of course, as well as Pam Shriver and Steffi Graf and Tracy Austin and Martina Hingis and Ana Kournikova most of the time, even when some male reporters seemed to be summoning their inner Humbert Humberts in person and in print. Female players had marvelous role models – the pioneers who fought for respect and prize money, most notably Billie Jean King. Some women had to face sniggering sexuality questions, most notably from the Beastie Boys of the British press, at post-match press conferences. I remember one female player being asked whether she was wearing an engagement ring from the woman in the family box. The volunteer steward at the Wimbledon interview room in the '80s was a mannered scion of a major British firm, who would wave off some personal questions – “please, tennis questions only.” I have seen John McEnroe and Martina Navratilova tell him politely they were more than equal to the questions. Which they surely were. Up to now, Naomi Osaka has been able to handle herself – on the court and in the media conferences. Her manifesto seems to have come from within, without advice from family or agent or coach or friends. Nobody seems to know the origin of her phrase “mental health,” but surely Osaka has seen players be mad or hurt by questions after a loss or a dispute. Perhaps she has been, also. I can only hope she is talking with people who care for her, including veterans of the tour – Evert and Navratilova. I would suggests she check in with a Black pioneer like Leslie Allen of New York City, who was on the tour back in the day when prize and endorsement money was measured in tens and hundreds. Unless there is more to Osaka’s angst than we know, she needs to remember that if she can face down the great players on today’s tour, she can handle the Beastie Boys (and Girls) in the media room. We’re the easy part. Four superstars, overlapping. I am referring to Rafa Nadal, one of the nicest people I have met in sports, who won his 13th French Open on Sunday. I am also referring to Chris Clarey and Karen Crouse of the NYT, who wrote about Nadal in the Monday paper. And I am also referring to Art Seitz, master tennis photographer, who has been snapping away, well, forever. I loved reading about Nadal and seeing Art’s photos, having become a Nadal fan in 2011, the only time I met him. I had heard he was a good guy, a sportsman, and he lived up to his reputation on a miserable day, with the remnants of Hurricane Irene lashing New York much as the tail end of Hurricane Delta was drenching New York on Monday. He had done his obligatory media conference and was eager to get back to Manhattan, but he was promoting his book and had promised me a few minutes for an interview. We got into a conversation, and I mentioned that I had covered eight World Cups by then, including my first, in his country, Spain. I think it's fair to say that reporters do not expect their subjects to show much, or any, interest in them. But Nadal seemed intrigued that an American knew and loved soccer, even my modest dose of knowledge. I knew that his uncle, Miguel Angel Nadal, had been a mainstay for Johan Cruyff at Barcelona in La Liga in the 90s, and I had covered Spain’s World Cup championship in 2010. So we talked soccer…as well as tennis….as well as his penchant for cooking for himself and entourage on the road. He could have ducked out at any time, but he stayed and talked, and my impressions of him since have been confirmed – a centered person who has willed himself to the top of tennis, and can speak with compassion about the pandemic, knowing it is more important than tennis. My pals Chris Clarey and Karen Crouse caught him perfectly in Monday’s paper – Chris concentrating on the match and the career, Karen focusing on his values and his acquired trilingual abilities. When I first saw Nadal nearly two decades ago, he could not speak any English in public. Now he is eloquent, from the heart. Felicidades, Rafa. Chris Clarey:

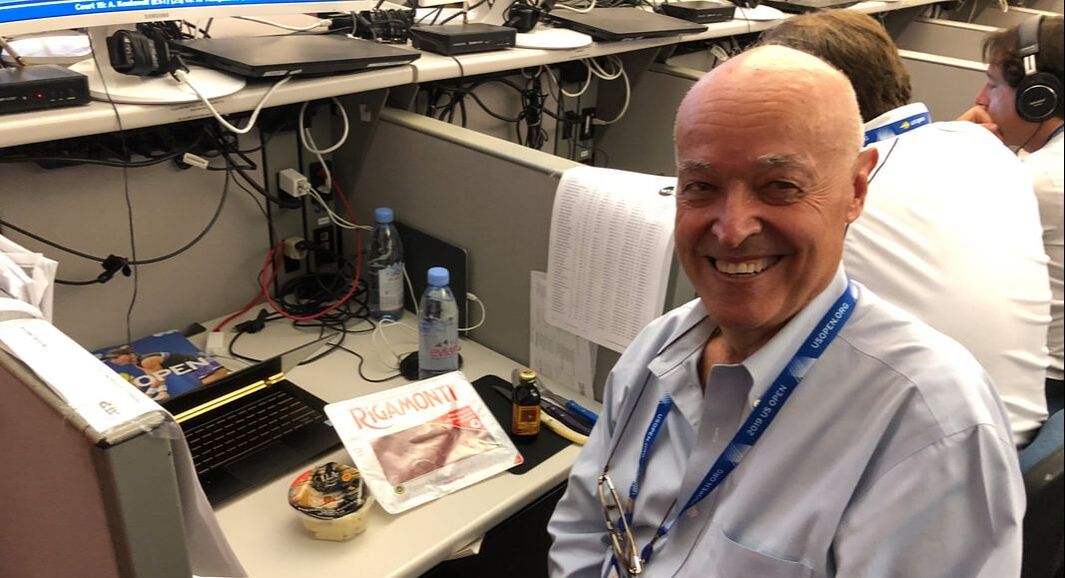

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/11/sports/tennis/nadal-french-open.html Karen Crouse: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/11/sports/tennis/french-open-rafael-nadal.html My article in 2011: https://straightsets.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/28/off-the-court-nadal-wears-chefs-whites/ For a sample of Art Seitz tennis photos, check out his Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/100001883302306/posts/4593499944056070/?extid=0&d=n Part of it is the tennis, of course. But I will admit, the high point of the U.S. Open these days, for me, is getting to see old friends and familiar faces, from decades of Opens and Wimbledons. Tennis is a traveling circus, quite unlike any other sport -- writers, commentators, experts, former players, coaches, business types, publicists and officials who pop up in sunny places from Melbourne to Monaco to Miami, kaleidoscopic yet permanent. (There was Virginia Wade, 1977 Wimbledon champion, with Queen Elizabeth II in attendance, looking as brisk as she did rushing the net, on her way, presumably to a BBC assignment.) I go to Flushing Meadows to see my friends, the ones who have survived the shrinking of the print-media corps. Some in this international rat pack seem to have been here forever –like Ubaldo Scanagatta from Florence, Italy, who files for three Italian papers and provides expertise on TV and radio on his site, Ubitennis.com. (In four languages.) Ubaldo – who turns 70 on Saturday -- knows how to live. On his annual fortnight in New York, he comes prepared with familiar food -- grated cheese (Colla Parmigiano Reggiano), olive oil (Esselunga Extra Virgin) and Rigamonti Bresaola, which is described online as “air-dried, salted beef that has been aged two or three months until it becomes hard and turns a dark red, almost purple color. It is made from top round, and is lean and tender, with a sweet, musty smell. It originated in Valtellina, a valley in the Alps of northern Italy's Lombardy region.” Even in these barbarian parts of the New World, it might perhaps be possible to find such Parmesan and Olive Oil and Bresaola, but Ubaldo takes no chances. He deigns eating with plastic, and therefore carries a real fork and a real knife in his kit, and when Italian players are not keeping him busy il mangia bene. One of the highlights of my journalistic career was before the Monday final in 2009, when Ubaldo invited a few American amici sportivi to the dining room, where he broke out the Parmesan, the Extra Virgin and the Bresaola. On Thursday I spotted Ubaldo in the Italian corner of the media writing room and I thought of other compatrioti famosi – Rino Tommasi, who analyzed the daily matchups on the Open programs for many decades, and Gianni Clerici, the squire of Lake Como, former amateur player (including Wimbledon, 1953), novelist, expert, with a waspish humor on and off the air. Clerici bestowed Italian heritage on Bud Collins, re-naming him “Collini.” But alas, Gianni does not come around anymore at 89, and neither does Rino at 85, and Bud passed in 2016. (The Media Center is named for him.) Many of my American friends are still typing and talking. A few days ago, I sat with tennis high priests Steve Flink and Joel Drucker during a match in Ashe Stadium, and also caught up with Johnette Howard, John Jeansonne, Wayne Coffey, Jeff Williams, Helene Elliott, Bob Greene, Anne Liguori, Chuck Culpepper, Andre Christopher and my tennis pal Cindy Shmerler. Three more were hanging together in the media center: NYT international reporter Chris Clarey, retired NYT columnist (but still active) Harvey Araton and Adam Zagoria, New York sports expert who writes for the NYT on occasion. Nice guy that he is, Adam took a photo of the three of us. For all the camaraderie, there is an air of nostalgia to the Bud Collins Media Center. A decade ago, the place bustled from morning to post-midnight with dozens and dozens of tennis writers from major cities – Boston, Miami, Denver, Orlando, Dallas, and on and on. There was a clatter of writers who were competitors but also friends – Robin Finn of the NYT provided a stash of Twizzlers (and really nasty nicknames for tennis stars.) Alas, falling circulation and earlier deadlines and changing Web priorities have cut back on the banter and the community.

The tennis endures. On Thursday, I watched in the lower press area of Arthur Ashe Stadium, as sixth-seeded Alexander Zverev of Germany matched his power and height against the mixture of power and drop shots of Frances Tiafoe, an American born in Sierra Leone. On a sleepy, sunny, pre-holiday afternoon, the predominantly American crowd urged Tiafoe as he befuddled Zverev in the second and fourth sets, but ultimately Zverev prevailed, 6-3, in the fifth. The fans surged out into the midway in search of refreshment or more tennis on the back courts. I went back to the Media Center to schmooze. The present is superimposed over the past. The U.S. Open began Monday by doing the right thing. A statue of Althea Gibson, pioneer and champion, was unveiled at the National Tennis Center, where she never played, at least competitively. Billie Jean King, Zina Garrison, Leslie Allen, Katrina Adams and Angela Buxton, Gibson's old doubles partner, all spoke of how Buxton was first. The statue, by Eric Goulder, is striking, as was Althea Gibson. Buxton, 85 and in a wheelchair, flew from London to recall how she bonded with Gibson on a pioneering mixed tennis trip to India and other countries. This belated honor to the first African-American player to play -- and win -- the "national" tournament is a prime example that this grand New York event is never only about these few weeks. The Open is about continuity. For all the crass, hard edges to the contemporary Open, there is still a faint whiff of gentility from the old Nationals in Forest Hills. Maybe it was the grass and the clubby atmosphere that mellowed people out. While tennis patrons this year are eager to catch a glimpse of Cori Gauff, age 15, to see if she just might be “the next” Naomi Osaka, or “the next” Sloane Stephens, the old champions still grace this event, in person or in perpetuity. I think of them every year as I visit the Open. I was reminded of Gibson this past week when Art Seitz, long-time tennis photographer from Florida, sent photos of Gibson that he had taken over the years. Seitz said he often met Gibson and found her to be friendly within the tennis circle, particularly to the young players, as tennis evolved to the age of King to Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graf and Venus Williams and Serena Williams and so many others.  Power and form: Althea Gibson serving in Florida, after her career. Photo: Art Seitz Power and form: Althea Gibson serving in Florida, after her career. Photo: Art Seitz The old champions are part of the Open, and so is the old site -- Forest Hills from 1915 through 1977. As a Queens kid of 10 or 11, I started taking the IND subway to 71st St/Continental Ave., walking to the little oasis of the West Side Tennis Club. The place was so tiny, so intimate, that you could literally rub shoulders with players as they tried, politely of course, to reach their grass court for a match. As a Brooklyn Dodger/Jackie Robinson fan, I was eager for glimpses of Althea Gibson, the first African-American to play in the “national” tournament. She made her debut in 1950 and did not last long those first few years, but her athleticism and drive were obvious. She reached the finals in 1956 and won it in 1957 and 1958, after which she retired from tennis so she could make some money, as incongruous as that sounds today. Gibson played professional golf and I think I saw her play as part of the Harlem Globetrotters tour that came to New York every March. But money never reached Althea Gibson as tennis became big business, and old stars often returned to add their luster to the event. As a columnist who covered the Open and often Wimbledon, too, I was never aware of Gibson giving a press conference or showing up for big-bucks from sponsors and patrons. Except to get Gibson's autograph a time or two on the crowded walkways of the West Side Tennis Club, to my regret, I never met her. The best reflection of Gibson on Monday came from Buxton, a British player in the '40s and '50s, who had eagerly played doubles with Gibson, winning the 1956 Wimbledon doubles. Buxton said that as a Jew she was also somewhat of an outsider in those years. Buxton told the crowd at the unveiling how her family in London was host to Gibson when she played Wimbledon, and how Buxton's mother introduced the two players as "my daughters." In recent decades, Buxton would come around and chat with reporters, with obvious affection and a sense of mission about her friend Althea. In 2003, she told a reporter that Gibson was "tall and lanky and rather like Venus Williams.” Gibson was said to wish the Williams sisters, as great as they are, would rush the net more, but that is contemporary tennis. articIn later years, Gibson was ill, at home in New Jersey. She passed in 2003.

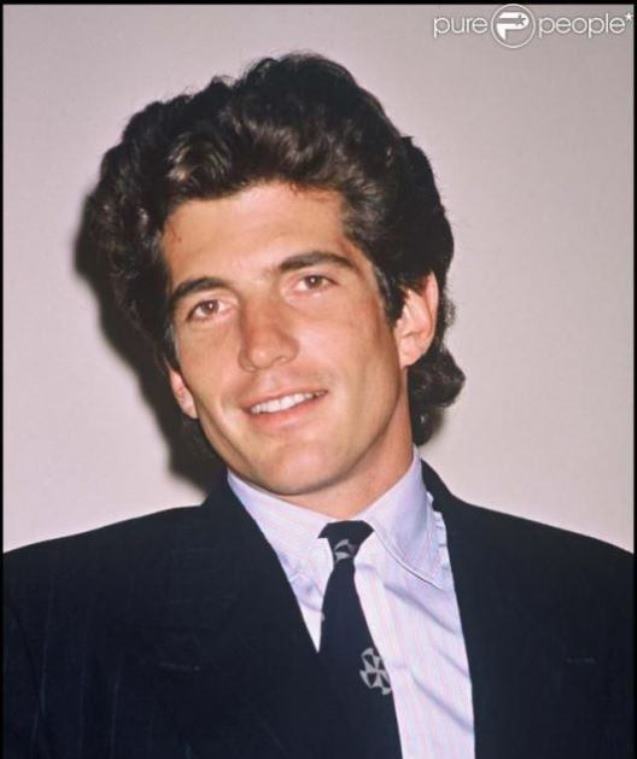

The city of Newark has put a statue of Gibson in a park, and now the USTA, through the of efforts of Katrina Adams, a former player and recently the president of the USTA. The talent and will of Althea Gibson are part of the Open, reflected by the current players, most of them tall and agile, like Gibson. We follow the new stars, and Althea Gibson’s image is with us forever -- on the lawns of the sedate little club a few miles away in another corner of Queens. * * * Obit, NYT, 2003: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/28/obituaries/althea-gibson-first-black-wimbledon-champion-dies-at-76.html?searchResultPosition=2 Current NYT article on the statue and how it got here: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/26/sports/tennis/althea-gibson-statue-us-open.html A Florida reporter's perspective of Gibson: https://www.nydailynews.com/os-xpm-2003-09-29-0309290251-story.html Gibson and "the Nationals" and Queens: https://www.6sqft.com/67-years-ago-in-queens-althea-gibson-became-the-first-african-american-on-a-u-s-tennis-tour/ The Facebook site for Art Seitz: https://www.facebook.com/ArtSeitz The classical music station was playing “Pavane for a Dead Princess,” by Ravel. It was beautiful, and I didn't know it, and I wondered why WQXR-FM was playing it on the second day of September while I was driving home from the US Open. Then I remembered: the Open of 1997, and another princess who died on Aug. 31, and how I saw her once at Wimbledon. Journalists see public figures, even on the sports beat: Jimmy Carter under the stands at Turner Field. Lyndon Baines Johnson on opening day in Washington, D.C. Hillary Clinton visiting the press box in Wrigley Field. And John F. Kennedy, Jr., right in front of me in Madison Square Garden. Coolest guy in the world. And Princess Diana at Wimbledon. I’ll never forget the eyes. The old press tribune was directly alongside the Royal Box. Princess Diana was on the guest list one day in the late ‘80s. We all checked her out early, and went back to our business. Later, I turned my head and caught those piercing eyes, looking back at us. Perhaps she wondered who that raffish lot was, as we chattered and gestured our way through the afternoon – a fitting Shakespearean upstairs/downstairs balance to the swells in the Royal Box. She should have heard some of the Brits with lurid commentary, imitating plummy royal accents. I’d like to think she would have laughed. Her two little boys were scuttling around the box, watched by helpers. Their mom was checking things out, with the curiosity we read about, her concern for the underclass, that is to say, us. I don’t know that she cared much about the tennis. She certainly seemed to be a seeker. * * * One evening in the mid ‘90’s, John F. Kennedy, Jr., was sitting in front of me at the Garden, a couple of rows up, behind where Spike Lee sits, facing the Knicks bench. He arrived late, wearing a nice suit, probably just came from work. He was by himself, and he appeared to be starving, keeping one eye on the game as he devoured a hot dog. Then he went to work on a large sack of fries. Just to Kennedy’s left, a boy around ten years old was staring at him. Either the boy knew who was sitting next to him, or he was salivating from the proximity of the fries. Kennedy popped in a few more fries. Did not turn his head. Did not smile or try to ingratiate himself with the boy. But like a point guard making a blind pass, Kennedy held out the bag of fries and shook it. The boy knew a good thing, took a handful. I don’t think he said a word but then again, JFK, Jr., was not looking for thanks. That was not necessary between a couple of guys who understood each other perfectly. The pass. The dunk. Kennedy understood hunger; the boy understood generosity. * * * After hearing Ravel’s “Pavane” on the car radio, I came home and googled up the music, written in tribute to a patron from the Singer sewing machine family, Winnaretta Singer, who was in a lavender marriage with the Prince de Polignac. Our age has few princesses, few princes, worth noting. I remember Diana’s piercing eyes, and how JFK, Jr., could see out of the corner of his eye.  Once House of Horrors, Now Practice Court for John Isner; Next Year, Gone. Once House of Horrors, Now Practice Court for John Isner; Next Year, Gone. Strictly by coincidence, the Times has a feature on the Op-Ed Page Saturday about the vanishing storefronts of New York, victims of rising rents. I was already planning my ode to the vanishing landmark of Queens, the house of upsets, the cramped, smoky pit known as the Grandstand. Once upon a time it was the second court at the United States Open, an afterthought grafted onto the main arena, Louis Armstrong Stadium, itself a tennis improv. But now in the name of modernity, the Grandstand has been phased out. It is serving as Practice Court 6 for this year’s Open but then will be bulldozed, gone, like ancient temples destroyed by vandals. The Open is one of the two best sporting events in my home-town, along with the one-day phenomenon of the Marathon in the fall. I can look past the money and the privilege and see the Open, with its roots at the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, as still very much a Queens event, right off the No. 7 elevated train. This year the Open has a new retractable roof over Ashe Stadium to keep the show moving when the monsoon hits. The Armstrong will be replaced by a new second stadium. The Open also has a new generic bowl, called the Grandstand with 8,200 seats. I am sure it has more amenities than the old Grandstand but it does not exactly have the feel of an Elizabethan bear-baiting den. For many years, the players had to inhale the meaty fumes from a restaurant suspended above the west stands. Something was always out to get the favorite at the Grandstand: In 1985, Kevin Curren, the fifth-seeded player from South Africa, was bumped off in the first round by upcoming young Guy Forget of France. Curren promptly emitted a Hope Solo solo, blaming the site for his troubles. “I hate the city, the environment and Flushing Meadow,” Curren said. “There is noise, the people in the grandstand are never seated and it takes an hour and a half in traffic to get here. It’s sickening that with all the money they get from TV, the USTA doesn’t build a better facility. The USTA should be shot. And they should drop an A-bomb on the place.” Curren was not the only player to get bushwhacked in the Grandstand. On Friday I ran into a former player who had benefited from the blood lust of the fans. In 1981, Andrea Leand, all of 17, met second-seeded Andrea Jaeger in the second round – in the Grandstand. “Andrea was up a set and 5-2,” Leand recalled. “I could hear a broadcaster saying, ‘That’s it, she’s done.’” Then again, you could hear everything in the Grandstand. “I heard a man asking his son, ‘Do you want a hot dog?’” The mob began howling for a new victim to be sacrificed to the Grandstand deities. “The sound went right through you,” Leand recalled with a beatific smile. She beat Jaeger, 1-6, 7-5, 6-3. It could happen to anybody, and often did. The litany of Grandstand upsets is long – best left to an expert like Randy Walker, who last year wrote a farewell to the Grandstand, well worth reading: The great thing about the ramshackle center of the 80’s was that reporters could watch Grandstand matches from the back of the press box in the main stadium. One match turned into a heavyweight fight -- Roscoe Tanner, one of the hardest hitters on the tour, and Chip Hooper, a big fellow, trying to drill each other, up close and apparently quite personal. This being the yappy borough of Queens -- Trump! McEnroe! Archie Bunker! -- the fans egged them on. Competition was also nasty in the lines as fans tried to get into a match that had suddenly turned epic. I visited the old den the other day – a few fans watching John Isner and a hitting partner whacking the ball around, but no yelps from fans seeking a new victim. The Grandstand could have served forever as an anarchic, irregular heirloom – a tribute to history. But Open executives can still revive the gritty aura of the old place: pipe fumes from the grille directly onto the court. Kevin Curren would feel right at home. For so many years, the schedule of a sports columnist took me far from home on the birthday of my country, on my own birthday.

“Do you remember all the places you’ve been?” my wife asked. Sometimes she was with me. Sometimes she wasn’t. Companions get used to journalists being away -- weekends, nights, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries. My wife recalls my taking a day's drive to the mountains on our first month in Kentucky -- and being gone for New Year's after a mine blew up in Hyden. (After that, I kept a change of clothes in the car.) Reporters head toward danger, not totally unlike police and fire officers. But I was a family guy and could be hard to find by the office when a child had a big game or we had company. But sports reporters often work on scheduled events and cannot avoid being away holidays and weekends. It's easier for a man than a woman to forage for a meal on the road. In her Sunday column, Maureen Dowd describes the snooty reaction to a single female diner in a Paris hotel. Alas, her good meal was spoiled by the rancid presence of Boris and Donald in her active mind. My birthdays were often spent on the road. When I was at Wimbledon, I would scan the Times, which ran a daily box of birthdays of notables. I never expected to see my name – and never did – on July 4 but I was always happy that George Steinbrenner was a non-person in the UK, and I hoped Pam Shriver would be mentioned. I never mentioned my birthday to colleagues; why draw attention in a press room? But in the age of the blog, here are birthday highlights of a travelling journalist: 1939: Born the day Lou Gehrig delivered his farewell speech in Yankee Stadium, I was a Brooklyn Dodger fan at birth. The ‘60’s: a blur of Mets and Yanks, three children being born, great times. Was I in Minnesota…or Shea Stadium….or home? Can’t remember. 1970: We took the family to Italy for a glorious month. I can’t remember where we were on July 4 – possibly the side trip to Switzerland – but I do know that on July 9, Corinna’s birthday, my wife arranged a cake on the hotel patio, off the Via Veneto. 1976: Bicentennial Day. Now a news reporter, I was assigned to a destroyer in the Hudson, where Henry Kissinger was on board. Asked about the raid on Entebbe the night before, the Secretary of State said in his gravelly accent, “You people know more than I do.” 1982: I was alone in Barcelona, covering my first World Cup. On the night of the Third, I went to a concert by Maria del Mar Bonet in a plaza. The next day I went to El Corte Inglés and bought a vinyl record of hers, which I still play, in memory of a lonely but beautiful night. 1986: We landed in Moscow for the Goodwill Games. A grim customs agent inspected my passport and suddenly he smiled and said, “Happy birthday” in English – the start of a lovely three weeks, glasnost in summery Moscow. Wimbledon: The English always honor the Original Brexit with flags flying, burgers in pubs. I would buy a bag of cherries in Southfields and sit with a friend and listen to the military band play American music before the tennis began. 1990: We woke up in Naples after Argentina beat Italy on penalty kicks in the semifinals of the World Cup, and we took the train back to Rome, celebrating the day in the trattoria beneath our flat near the Piazza Navona. 1994: Tab Ramos was cold-cocked by Leonardo in the round of 16 at Stanford. I bought a great t-shirt with American and Brazilian flags; it recently fell apart. After dinner with Filip Bondy and Julie Vader in Palo Alto, I caught the red-eye to Boston for another match. 1998: Dennis Bergkamp scored in the 90th minute as the Netherlands beat Argentina, 2-1, in Marseilles. We were staying in Aix; my wife had gone shopping in a market for presents. 1999: A joint birthday celebration, for me and ace photographer John McDermott in San Francisco, with family, the night before steamy July 4 semi of Women’s World Cup, a 2-0 victory over Brazil. 2004: Alone in a motel in Waterloo, on the Lance watch, reading David Walsh’s book that pretty much convinced me Lance was cheating. (The masseuse who was ordered to lie about saddle sores!) Watched Greece beat host Portugal in Euro final and wrote paean to underdogs. 2005: Roger Federer beat Andy Roddick in the Wimbledon finals. Next morning we took the Eurostar to France to pick up Lance’s bid for a fifth. Two days later, we heard that nihilists had set off explosions in the London transit. 2006: In our hotel in Berlin, watched Italy beat Germany, 2-0, in semifinals, then went out in streets to interview rollicking fans, celebrating a good run with beer and curry and ever-present wurst. 2010: Jeffrey Marcus drove from cold, inland Johannesburg to the fresh salt air of Durban for the Germany-Spain semifinal two days later. My unexpected birthday present: chatty Indian staff and glorious smell of curry from the dining room -- a treat for a journalist who picked an odd day to be born. (Birthday wishes to Pam Shriver, John Hewig and John McDermott, all over the globe.) No sport carries a sense of community like tennis. Even with gigantic prize money and swollen retinues of today, the sport remains somewhat a caravan of gypsies familiar to each other, even though their occupations vary – players, coaches, hitting partners, significant others, moms and dads, agents and publicists, plus the specialists who cover the sport: the peripatetic photographers plus the scribblers and babblers, as Bud Collins called himself and his colleagues.

Arthur Worth Collins, Jr., was the center of one sport, more than any other journalist has ever been. In his half century on the beat, tennis has been a movable feast, seeking warm spots year round – Monaco in April, Wimbledon in late June, Australia in January – jet-lagged regulars taking the rays during a desultory early-round match in some tune-up event. Collins could doze in the sun with the best of them, as recalled by Bill Littlefield of WBUR radio, who spoke at the memorial service for Collins in historic Trinity Church on Copley Square in Boston last Friday. Littlefield talked about Collins the writer – often overlooked amidst his garish pants and equally garish vocabulary – who could describe the sound of tennis balls being “punished,” yet make it a soft, pleasurable backdrop to life itself, like a heartbeat. Collins was the heart of the sport for decades, back to the late 60s when he shifted from a general sports reporter who recognized the special ones, Muhammad Ali and Bill Russell and Billie Jean King, becoming a tennis maven. He brought people together at events around the world, said Lesley Visser, once a Globe sports writer, now a broadcaster, who recalled how Collins could write a column and simultaneously answer questions from colleagues, always ending with some version of “ciao” in their native tongues. (He addressed me as “VAY-chay,” which is how real Hungarians pronounce my name. Three Italian insiders – Gianni Clerici, Ubaldo Scanagatta and Rino Tommasi – in turn called him “Collini.”) Collins, in failing health for years, passed on March 4 at 86, and his wife and protector and caretaker for two decades, Anita Ruthling Klaussen, spent three months preparing a ceremony -- on his birthday -- that was both elaborate and parochial in that most hamish of great American cities. The service was both stately Episcopalian and randy jock. In the pews were familiar faces, and forehands, of Rod Laver, Stan Smith, Todd Martin and Pam Shriver, as well as tennis officials from around the world, and journalists who knew Collins both as friend and source (oh, and by the way, a very accomplished "hacker" in the tennis sense of the word.) Two great champions spoke. Chris Evert recalled being a monosyllabic 16-year-old, feeling the kindness of Collins, and later, when she lost seven Wimbledon finals to a rival whose name she did not need to pronounce, Collins was always at courtside, doing a worldwide live interview “in those silly pants,” but with a kind smile that showed he understood the pain of being second on that day of days. Billie Jean King, wearing a pink blazer in tribute to the people who died in Orlando a week earlier, captured the day, for me, because she was once again Mother Freedom – nickname courtesy of Collins – and like Evert she remembered being interviewed by Collins at 16 and finding she could talk to him. King's talk was disciplined, smart and passionate. She remembered Ali once telling her that people had to always be ready for the moment. She found that trait in Collins, always in tune to the colors and tones and spins and bounces of that day, living in the moment, working hard, enjoying himself. The congregation was elderly, many people moving slower than they used to. Hundreds of them came from a world where everybody followed the sun, hearing the brassy notes from the Pied Piper who was at the core of their world for so long, and so well. This was at the United States Open five or six years ago. I was sitting outdoors with a couple I knew from the Deep South, tennis fans who had spent a lot of money to be in New York for a few days.

Bud Collins hove into sight, moving fast, sweater thrown jauntily over his shoulders, couple of his books he had been pushing in one hand, and wearing a dazzling pair of pants, made from material he had discovered in some haberdashery or curtain emporium in Mumbai or London or wherever. My friends brightened at this dazzling sight and looked to me to see if I could slow him down. Bud absolutely screeched to a halt to greet the couple, tennis fans, his people. I made the introductions, he chatted, picked up on their charming accent, tossed off a quickie memory of their home town, and then he was off, down the lane, moving fast. “He’s probably due on the air in 30 seconds,” I said. They were in awe. Bud Collins was the core of tennis, the man who brought it to their town via his pioneering multisyllabic imaginative narrative of tennis, the men and the women. He came up with nicknames: the mysterious computer rankings ("Medusa"), a love-love blanking ("bagel job"), the dominant German star Steffi Graf ("Fraulein Forehand"), the ultra-composed Chris Evert ("The Ice Maiden") and the powerful Venus and Serena Williams ("Sisters Sledgehammer"). (List from John Jeansonne of Newsday.) Bud gave life and form and history to tennis. I cannot think of any single journalist/broadcaster/historian that embodied any sport as much as Bud. He was tennis, roaming the earth, the warm places, where players cavorted on red clay or grass or synthetic stuff. Bud followed the sun, bringing his glittering wardrobe with him. His defining moment was at Wimbledon one year when Martina had just beaten Chris (no last names needed in Bud’s world) in the finals, and Bud was working for NBC. He stood there with his microphone, and Evert dutifully trudged over for the mandatory interview and she looked him up (ruddy face, frilly shirt) and down (pants looking like watermelons or cherries) and then, before he could launch into his introduction, she said drily, “Nice pants, Bud.” Over worldwide TV. Bud also played tennis. Back at the dear old West Side Tennis Club in the mid-70’s, I saw him scampering around a celebrity doubles court, barefoot. He coached the sport at Brandeis years ago. Bud was the memory of the sport, always willing to answer a question when we all were on deadline. He had once taken a spot of tea with people who had won Wimbledon decades earlier. Lefty or righty? Personable or dour? Bud would fill you in. Bud has been winding down the last few years, in front of our eyes, Father Courage trekking to the Open with the help of his indomitable wife, the photographer Anita Ruthling Klaussen. Last year the United States Tennis Association named the media center for Bud and Bud got there, in a wheelchair, wearing nice pants. Billie Jean King recalled Bud's respect for women’s tennis. I recalled how, when I broke in, Bud was covering all sports for the Boston Globe, in the avant-garde of the Chipmunks, the youngish reporters who respected not only Muhammad Ali’s chosen name but also his importance. Before he was a tennis maven, Bud was a versatile journalist. One thing I noticed that day was the women players who chose to show up for the ceremony. Bud perked up when he spied Katrina Adams, the president of the USTA, and called her a “Wildcat,” a reference to her college, Northwestern. He could see Billie Jean, of course, and also Martina and Rosie and Tracy, faces in the adoring crowd. (Harvey Araton, the Times’s resident voice of sports memory, wrote a sweet column that day.) Since then, people have been keeping in touch, via Anita. Billie Jean King dropped in one day when she was in Boston. Mary Carillo stayed in touch. So did Lesley Visser and Cindy Shmerler, a tennis authority herself, who recalls a couple of high points of her wedding -- playing tennis with Bud in the morning, dancing cheek-to-cheek with him at the reception. . Bud passed today – Friday morning. There will be longer, fuller obituaries, and details of a memorial in Boston around what would have been Bud’s 87th birthday, June 17. I just want to thank Bud for stopping and chatting with that couple from the Deep South, and for personifying his sport. Nice pants, Bud. There’s a nice letter in the Sunday Times describing the kind way Andy Roddick reached out to a 13-year-old who had been diagnosed with leukemia in 2002.

The letter, from Andrea H. Ciminello, says her son, Adam Ciminello, is now a leukemia survivor and a Brandeis graduate, and that Roddick “remains a champion” in the family’s eyes. Roddick is a bit busy this weekend, playing tennis. Then again, Adam Ciminello is a bit busy, making music in his studio. (He plays the piano and sings and writes his own songs.) But Adam had some time on the phone Saturday to describe how he came to know Roddick, who was only 19 at the time. Members of Adam’s family made contact with Roddick’s web site in 2002, saying that the 13-year-old tennis player and Roddick fan was undergoing chemotherapy. Blanche Roddick, Andy’s mother, contacted Andrea Ciminello and they talked, as mothers. Then the young professional, traveling all over the world, began getting in touch with Adam. “For a while, we would talk every few weeks,” Adam said. “This was back in the day when people used answering machines. He would leave a message, and he would call back. “We didn’t talk about ‘hang in there’ or “stay strong,’ things the hospital social workers might say with me,” said Adam. “I suppose if I had wanted to talk about it, he would have. But we talked about girls and movies and pop culture.” One time Adam and his family attended a clinic Roddick was giving at Rockefeller Center, and he met Andy and James Blake – “another great guy.” Another time the Ciminellos, who live in Poughkeepsie, on the Hudson River north of the city, got a call that Andy was playing in a few hours at one of Billie Jean King’s World Team Tennis events in Schenectady. The family raced upstate, not knowing how it would work out, but Roddick spotted them in the crowd and found them box seats. “He joked with me during the match,” Adam recalled. “He would say, ‘Adam, where should I play this one?’” A third time, Roddick spotted Adam during a practice at the U.S. Open and talked to him, without interrupting his work. In 2003, Roddick won the Open, still his only Grand Slam championship. A few weeks later, Adam found a message on the machine, something like “Sorry I haven’t called but things have been a little crazy around here.” Adam estimates Roddick called 15 times over three years. “He could have given me a signed poster and I would have been psyched,” Adam said. “He never did anything for personal gain. If anything, we played it up more than he did.” At some point, they fell out of touch. Adam played high-school tennis and then discovered other pursuits, which is often how college works. He takes an annual blood test and EKG – “and that’s it.” At the moment, Adam is working for his parents, Paul and Andrea, who run their own company, Ecosystem Strategies, Inc. Adam is just starting out as a musician at 23; his pal is retiring from the tennis tour at 30. As part of his farewell press conference, Roddick made a few jokes about his sometimes testy relationship with the media. It’s his thing. I usually smiled when he dropped a sarcastic line on me or somebody else asking a dumb question. (They were always dumb questions.) I got his humor, which sometimes was meant to deflect the thoughtful guy inside. Adam Ciminello says Roddick did not have to keep in contact. The important thing is that when a kid was lying in a hospital, receiving chemotherapy, and just dreaming of hitting tennis balls again, Andy Roddick was there to chat about all the good stuff. I haven't been slacking off, honest. Been going to my favorite New York sports event, the Open.

Working on a piece about night matches. The players love it. This is a bittersweet Open because Kim Clijsters played her final singles match on Wednesday. Anybody who caught her interview on ESPN2 last evening will understand why she is widely called the nicest person in tennis. She talked about her late father, Leo Clijsters (whom I saw play defender for Belgium in the World Cup) as a role model, even if he didn't start off knowing much about tennis. Her praise for her father matches that of James Blake, who is playing a match late this afternoon in Armstrong. He also gives credit to his late father for encouraging him. Blake is having a modest resurgence this summer. We cannot have too many mature and gracious athletes like Blake and Clijsters. Off to the Open. . There is nothing in sport quite so public and naked as watching a tennis star trudging off the court after a first-round elimination.

Tennis fans have seen it twice in the past week, as Serena Williams and Andy Roddick were eliminated in the first round. No place to hide. Just blindly stuff the gear in a bag, maybe manage a wave, and vanish from sight. This is what draws people to tennis – the loneliness of the singles player, carrying a persona, a resumé, an expectation of still being able to dig something out of muscle memory. In no other sport is the defeat so early, so finite. Tiger Woods failed to make the cut. Yes, the words still shock, but even the-artist-formerly-known-as-Tiger is performing in the pack, just another name on the board, his score outside the Mendoza line of the second-round cutoff. Boxing? Yes, I’ve seen a very old Joe Louis training for what everybody (including Louis) knew was going to be a demolition by Rocky Marciano. (My dad took me to Louis’ training camp in New Jersey. Louis was solemn, and miserable, and old.) Great boxers can run out of time in front of the world. But in that violent business, every fight has the potential for danger, for sudden ends. The first round of a tennis tournament? That’s no time for a star to be eliminated. We all know that players go downhill. One of the most poignant – and funniest – columns I ever wrote was from Wimbledon in 1991 when Pam Shriver shared the shabby details of being an unseeded player, after all those years, and having to change in the No. 2 dressing room. This most human of players described the wallpaper in the locker room -- Stripes. Plaids. Flowers. Remnants. She made us laugh. She made us cry. That’s why she’s Pam Shriver. I’ve posted it on this link. As merciless as time can be, it is still a shock. Baseball players and basketball players can slip downhill, finish up on the bench, get released in a paper transaction in the off-season. But marquee tennis players are out there alone. All right, so Roddick was – past tense, sort of -- a big-serve finalist at Wimbledon, a one-time champion at the U.S. Open. He still carries that aura, although clay was never his surface, even when he was a contender. Williams has been a charismatic and powerful champion. It’s hard to see her without thinking of her outbursts at the U.S. Open in 2009 and 2011. That’s part of the package – an intimidator, who does not encourage sympathy. That’s the thing about stars. We know them for their sarcasm and their bluster as well as for their victories. Then one day they are stuffing racquets into their duffel bags while the true fans give them respectful applause. Still a cruel sport, punctuated by those long steps off the court, alone. |

Categories

All

|