|

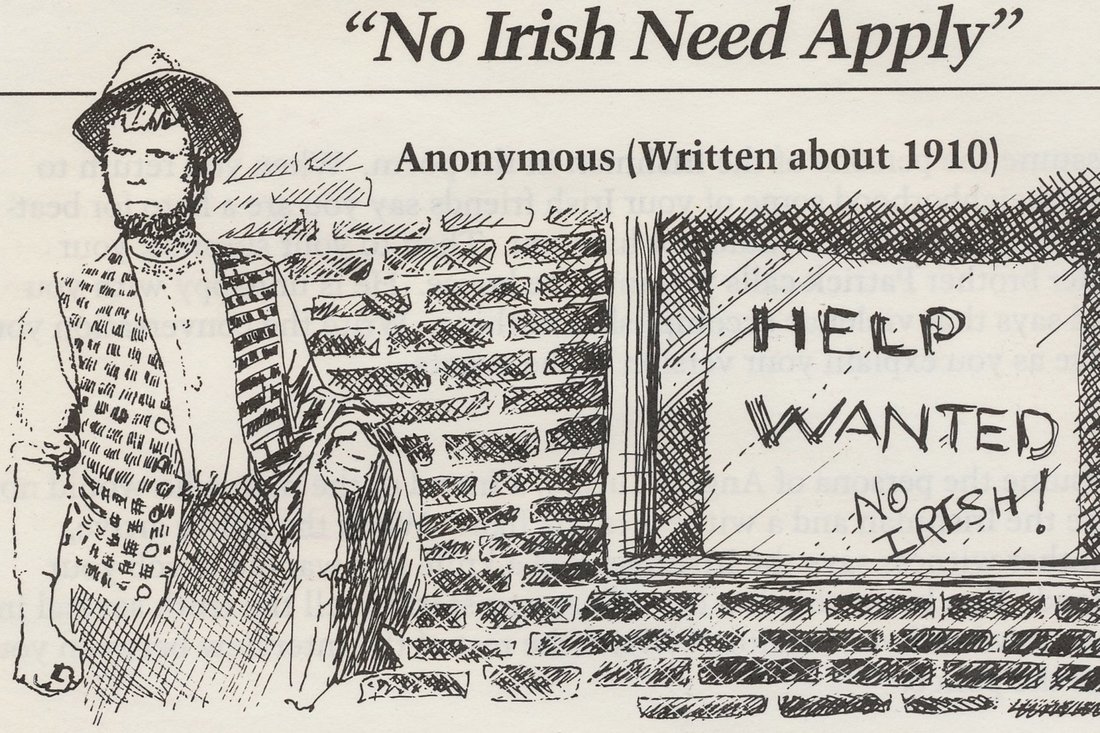

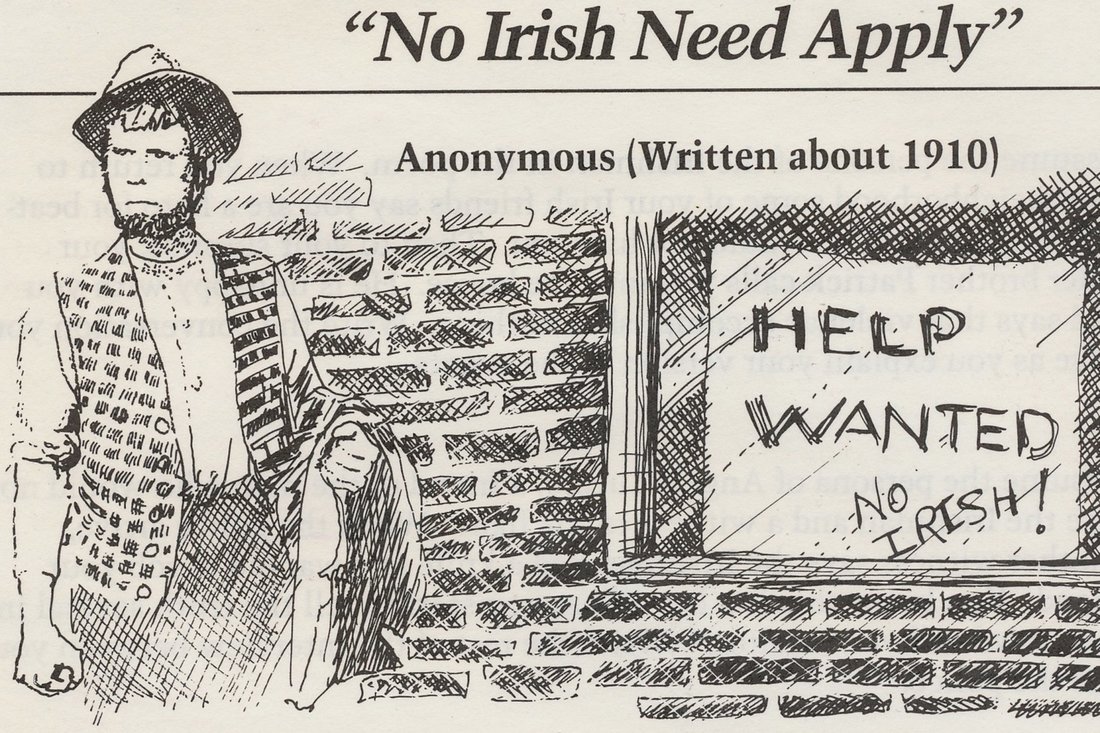

Lately, some friends have been asking what I'm doing. My answer is, I've been trying to pitch in more -- plus keep in touch with family and friends -- plus follow the Mets. That does not leave much time for feeding my personal beast on the Web. *** We've also been discovering the little treasures that pop up on the two public channels in our area -- Channel 13 and WLIW21. For a year or two, we were caught by a Swedish series, "Before We Die" -- Stockholm cops, Euro crime family, tangled family ties -- that gave me chills I had not experienced since "The Sopranos." (Later, a British version of "Before We Die" proved to be a gabby failure.) This past winter we got hooked on a French series, "Astrid et Raphaëlle," about a Paris cop who notices that an office worker is autistic, and has the ability to notice and decipher clues, physical and psychological. Before long, the inspector is taking Astrid along on cases -- relying on her intuition. I often wonder how Astrid, the French-Norwegian actress, Sara Mortensen, manages to change gears from her introverted persona when she goes back into the real world. *** As a former news reporter, I am fascinated by the police methods in "Before We Die," and "Astrid et Raphaëlle." And that brings me to "The Brokenwood Mysteries," in a small New Zealand town that seems to have more than its share of characters -- golfers, actors, a snarky young Maori guy -- and an extraordinarily high murder rate. Good grief, we once visited friends in Wellington for a week, and NZ seemed like the most civil place in the world. The Brokenwood series began a decade ago, without my knowing, and at some point there was a new inspector with his own dark side-- Niall Rea, who makes no secret of his past divorces (three? five?) and he admits he deserved every one of them. He also has well-developed detective skills, and quickly makes the judgment that the local assistant, played by Fern Sutherland, is smart and brave, and he treats her with respect. I like the New Zealand police series whereas I scorn the British detective series on the tube because the folksy bumpkin detectives are always explaining things to the suspects. Shut up, already. Detectives keep things to themselves; they do not conduct therapy sessions for their suspects. In a recent episode from "Brokenwood," a suspect is entitled to a suave lawyer, who protects his client, Just like real life. The most recent episode of "Brokenwood" had a country music theme -- the regional star breaks the news that she is moving to, of course, Nashville. Needless to say, she does not live out the night. With my background of helping write Loretta Lynn's autobiography, "Coal Miner's Daughter," traveling around with the Loretta entourage, I am familiar with the fans -- known as "the bugs" to my old musician pals on Loretta's bus. Rea's detective, himself a country buff, notes that avid fans know everything about the mysteries and jealousies of the traveling band. "Brokenwood" was filmed a decade past, and the personnel has moved on. If the inspector and the assistant fall for each other, please do not tell me. *** More public TV: Irish music, including including a series of intimate performances in lovely Irish castles, in a series called "Tradfest." The interviewer is Fiachna Ó Braonáin, a longtime member of the great Irish band, Hothouse Flowers. My wife and I love how the musicians respect each others' work. So that's what I've been doing in my spare time, instead of typing.  (I can write this, since I carry an Irish passport, courtesy of my grandmother, along with my beloved American passport) Stephen K. Bannon runs our country, pushing the buttons of the distracted oaf who is technically the president. Trump shows what is under his personal rock when he refers to Jon Stewart as “Jonathan Leibowitz” (the comedian’s original name) after a TV gig. Guess Trump forgets he was passing as Swedish as long as he could, neglecting his family origins as Drumpf. Behind him is Bannon, pulling the strings, telling him how to keep Muslims out of the country. I looked it up. http://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Bannon Bannon means “white” or “fair” – in the complexion sense, you may be sure. As an Irish passport holder, I can say, some of Trump’s closest advisors are named Flynn and Kelly and Bannon. It was not that long ago that “real” Americans considered people from Ireland the unwashed, the others, the threat. The Flynns and Kellys and Bannons were not considered good enough to haul trash or dig graves for “real” Americans, who had, of course, killed and dislodged as many original Americans as they could. There is reasonable debate about how many Irish ever encountered signs that said NINA -- No Irish Need Apply. Butongoing research proves it was there, in some windows, some newspapers, many hearts. The Irish persevered, and a descendent of Fitzgeralds and Kennedys became president. Now another president talks about a “ban” of Muslims, a registry of Muslims. He backtracks, but we know. In a dangerous world, the U.S. was already vetting people from dicey parts of the world. But with his tiny attention span, the new president tries to stop legal residents of the U.S. from coming home. Doctors. Scholars. Husbands. Wives. He is unashamed. He knows no history. Knows only fragments of things that flutter in front of his eyes. Knows only what Bannon tells him. It’s easy to spot the sneer on Bannon’s face. We want this guy advising our shallow president?  (I can write this, since I carry an Irish passport, courtesy of my grandmother, along with my beloved American passport) Stephen K. Bannon runs our country, pushing the buttons of the distracted oaf who is technically the president. Trump shows what is under his personal rock when he refers to Jon Stewart as “Jonathan Leibowitz” (the comedian’s original name) after a TV gig. Guess Trump forgets he was passing as Swedish as long as he could, neglecting his family origins as Drumpf. Behind him is Bannon, pulling the strings, telling him how to keep Muslims out of the country. I looked it up. http://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Bannon Bannon means “white” or “fair” – in the complexion sense, you may be sure. As an Irish passport holder, I can say, some of Trump’s closest advisors are named Flynn and Kelly and Bannon. It was not that long ago that “real” Americans considered people from Ireland the unwashed, the others, the threat. The Flynns and Kellys and Bannons were not considered good enough to haul trash or dig graves for “real” Americans, who had, of course, killed and dislodged as many original Americans as they could. There is reasonable debate about how many Irish ever encountered signs that said NINA -- No Irish Need Apply. But ongoing research proves it was there, in some windows, some newspapers, many hearts. The Irish persevered, and a descendent of Fitzgeralds and Kennedys became president. Now another president talks about a “ban” of Muslims, a registry of Muslims. He backtracks, but we know. In a dangerous world, the U.S. was already vetting people from dicey parts of the world. But with his tiny attention span, the new president tries to stop legal residents of the U.S. from coming home. Doctors. Scholars. Husbands. Wives. He is unashamed. He knows no history. Knows only fragments of things that flutter in front of his eyes. Knows only what Bannon tells him. It’s easy to spot the sneer on Bannon’s face. We want this guy advising our shallow president? The young lady in the change booth at Heathrow inspected my maroon Éire passport. “So, you are a plastic Paddy?” she said. This was my first time using my passport, two decades ago, and I was feeling quite proud. The shiny new passport had already gotten me through the European Union lane, quicker than the regular Arrivals lane, but now the change agent put me in my place. My newness, my American-ness, came through. Plastic, indeed. I think about her every St. Patrick’s Day when I rummage around for some vaguely green sweater or tie but decline to join any parade that might be taking place. My second passport, beside my beloved American passport, is courtesy of my grandmother, born in County Waterford in 1875. We lived under the same roof until she died when I was twelve (actually, it was her house, thrifty woman that she was) but I don’t recall her ever talking about the Ireland she left as a teen-ager. (I wrote about her three years ago.) Being Irish, via a maroon passport, is a state of mind, and I claim to be Irish, deep down inside. I say it is the moody, emotional side, the side that cares. I love to hear the trace of an Irish accent, particularly in women, newscasters on the BBC or Euro News, or the lovely staff at Foley’s on W. 33rd St., and a few friends (they know who they are.) Last Sunday, Christine Lavin was filling in for John Platt on WFUV-FM, and was host to Maxine Linehan in the studio, singing “Danny Boy” live. (This is not a song most artists rush to perform, just as jazz musicians charge extra for “When the Saints Go Marching In” at Preservation Hall.) But Linehan sang “Danny Boy” and damned if I didn’t get tears in my eyes. Being Irish is part genetic – and part choice. I had a three-week binge on “Ulysses” back at Hofstra, and now I re-read it every five years or so. I am touched by Seamus Heaney and Frank McCourt and the plays of Brian Friel and Sean O’Casey. My wife, with her own spouse passport, talks about a visit to Galway or Cork. Our one visit to Ireland (Canadians and Australians and Americans buying all kinds of green souvenirs), I remember the way old men chattered with each other, and one old lady who stopped us on a street corner in Ballsbridge and apologized for the heat wave. (It was 75 Fahrenheit, in July.) I file away some terrible things that have happened on the island. Life is complicated. But there are few days when I don’t remember the maroon passport in my desk, and my grandmother’s gift. * * * (Maxine Linehan, below. Go for it, it's St. Patrick's Day.) Top: Raglan Road. Below: classic concert at the Alhambra. Or your Jewish bubbe. Or your Italian nonna.

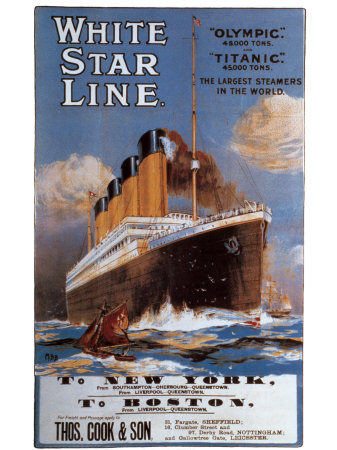

And don’t just listen. Ask questions, Get them to talk. This lesson was reinforced for me recently in a column about Christine C. Quinn’s grandmother, a passenger who survived the Titanic. As it happens, I also had an Irish grandmother with strong connections to the same White Star line that owned the Titanic. I am angry with my youthful self for not asking questions of my grandmother, or at least observing. Quinn was better at it. Quinn is the speaker of the New York City Council and a front-runner for mayor in 2013. As the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic approached, Quinn told Jim Dwyer of The New York Times how her elderly grandmother almost never talked about how she managed to get out of steerage and into a lifeboat on that terrible evening. Dwyer’s lovely column is included here: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/06/nyregion/christine-quinn-retraces-grandmothers-trip-on-titanic.html. Quinn said she knows a little about her grandmother’s adventure because she had the opportunity to ask questions when she was 13. “The only time we spoke about the Titanic was when she was recovering from a broken hip, and I asked her the story when we were hanging around her room,” Quinn told Dwyer. Now that I am a grandparent, I wish I had asked questions of my Irish grandmother, who mostly lived with us until she died when I was 12. I had plenty of time to observe her and ask questions, but, unlike Christine Quinn, I failed miserably. I can remember my grandmother as an old lady in a black dress, who took me, the oldest of five, to church, to the diner for breakfast, and a few times to the movies. I can see her visiting her old-lady friends on Adirondack chairs at Lake George in upstate New York. In my mind, they are all dressed in black, interchangeable. But I cannot even remember her voice – I think she had long since lost any Irish accent -- and I cannot remember her ever speaking about being Irish. If Bing Crosby would sing an Irish ballad on the radio about “strangers” who tried to impose their rule on the Irish, there was no response from my grandmother. Nana had long since become Anglicized and Americanized. And I never asked her – and she never told me, as far as I remember – how she got from County Waterford to the New York area. It involved a circuitous trip that I cannot piece together. I do know that my grandmother’s sister moved to Brussels and lived through two ruinous world wars, but my grandmother took a different path. And it also involved the White Star Line. When my mother was fading in her late 80’s, she mentioned that her mother had worked in South America as a governess, but by that time she could not supply any details. I know my grandmother spoke French from her frequent visits to her sister at Rue Sans Souci in Brussels. Did my grandmother also speak some Spanish? Did she work on the White Star Line to gain passage from England to South America? How did she meet the Australian-born ship’s officer whom she would marry, as they settled in Southampton? All gone now. My mother could remember being in Southampton in May of 1915 at the age of 4, and going down to the harbor as people grieved for family and friends who were lost on the Lusitania. The Titanic was part of her life, through her father. And after the war, the officer’s family immigrated in style on the White Star Line and ultimately settled in upstate New York with a large home and a nearby farm. I’ve asked my younger sister, Janet, who was the “pet” of my grandmother, if she could remember anything about Nana, but she was too young to take in those kinds of details. We all agree, we were not the kind to sit around and tell stories of the old days. I try to tell family history to our grandchildren, but the opportunities are rare. One of my grandchildren, the youngest, actually uses the old-fashioned implement of email to ask me questions about trips I take, and what I do. She shows promise. I am respectful and a trifle jealous that Christine Quinn had the sense to ask questions of her grandmother. I would urge everybody to do the same. |

Categories

All

|