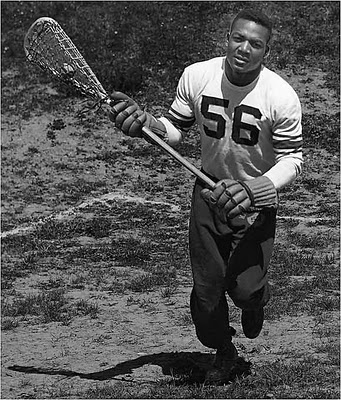

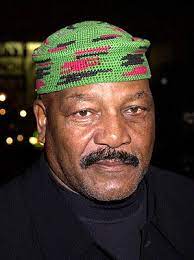

Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Here on the Manhasset-Port Washington tectonic plate (if there is such a thing), some people still feel the rumbling from Jim Brown, local guy, who died Friday at 87. They remember the earth trembling when Brown crashed into opponents in most of his five sports. (Correct: five sports.) They also remember the impact of his loyalty, when he chose to come home to Long Island. Brown was many things to many people (including a felon serving a few months for misbehavior toward women.) Bad side and all, Brown was surely an epic figure out of ancient legends – from Beowolf to Babe the Blue Ox to John Henry, the steel-drivin’ man. Some people remember, first-hand. I called my pal and neighbor, Paul Nuzzolese, who played three sports at Schreiber High in Port Washington. Paul’s family used to run a visible ice-and-wood business with trucks rumbling all over the metropolitan area. Paul played guard in football, was on the basketball team, and was a lefty pitcher on the Port baseball team. The plan for Jim Brown was to throw off-speed, not give the big guy something he could hit. And if you could induce Brown to chop a grounder, it was wise to avoid a collision. Were baseball opponents intimidated by the sight of Jim Brown on the basepath? Paul called me back Sunday morning after he recalled pitching at home against Manhasset, and being taken out when the game was tied after a regulation seven innings. That gave him a good view of Brown's 360-foot perambulation of the bases: "Brown hit a squibbler down the first-line," Nuzzolese said. "You know how hard it is to field a squibbler." Harder with fully-grown Jim Brown hustling down the basepath. (No names mentioned of the Port fielders.) The ball got past the first baseman, into right field, and Brown took off for second, and continued toward third. The Port third baseman waited for the throw, but was wary of Brown barrelling down on him, and needless to say Brown wound up scoring on the aforementioned squibbler. Port lost the game, but the fielders retained their knees, and their wits. Still, like Jim Thorpe and Michael Jordan, Brown was not a great hitter. “It was his fourth sport,” Paul said respectfully on Friday when he heard his old opponent was gone. In order, Brown played football in the fall, basketball in the winter, was a high jumper in track and field, and somebody will have to explain to me how he managed to play baseball and lacrosse in the spring. There are tales of Brown playing in a baseball game, and when Manhasset was not in the field, he would leap a fence to and take a turn at the high jump, and then return and take his turn at bat. How did Brown come to Manhasset, at the base of Manhasset Bay, a few minutes from Port Washington? Born on Feb. 17, 1936, in coastal St. Simons, Ga., Brown came north with his mother, who cleaned houses in adjacent Great Neck. But Manhasset introduced the young man to civic leaders and coaches who promised him he would be comfortable in their school, and he wound up registered at Manhasset. He soon made himself felt – particularly on the football field. Paul Nuzzolese, 86, was a guard, bulked up over 200 pounds, who saw and felt Jim Brown up close. He recalls a fellow lineman -- “Big Joe, six-foot-three, built like Hercules, had a collision with Brown in the open field – never was the same.” My friend was talking on the phone from Florida; I could hear the shudder in his voice. (I have to proudly add: My pal Nuzzolese is now a member of the Wagner College athletic hall of fame.) As good as he was in football, Jim Brown was said to be the best lacrosse player who ever lived. It was impossible to dislodge the ball from the webbing at the end of his lacrosse stick, tight in his powerful hands. The legend is that Lefty James, the football coach at Cornell, wandered over to watch a Syracuse-Cornell lacrosse game one spring and blurted, “My God, they let him carry a stick?” (I think my late pal Dick Schaap, who played a bit of lacrosse, may have told me that story.) The money was in the National Football League, and Brown was the best, or very close to it. His path took him to the movies and some notoriety in his so-called private life and also a major role in Black activism of the ‘60s and well into this century. All of that is covered in the great coverage in Saturday’s New York Times and surely everywhere else. And then there were the homecomings. In 1984, Brown had mellowed enough to accept the induction into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, but obdurate as he was, he would only show up if the ceremony was held in his adopted hometown of Manhasset. He honored Ken Molloy, civic leader, and Ed Walsh, football coach, and others who treated him with respect, more than just a five-star athlete. I made the short drive to cover Brown’s induction. In the informal moments, I introduced Brown to my son, then 14 years old. “Nice to meet you, David,” Brown said, in that deep voice, shaking hands vigorously. I distinctly remember a crunching sound, although David does not quite remember it being quite that bad. Brown came home other times. One of his Manhasset teammates, Mike Pascucci, had done well in business, and had become a booster of one of the great institutions on Long Island, or anywhere – then named Abilities, Inc., now named the Viscardi Center, after the founder, Dr. Henry Viscardi – in nearby Albertson, L.I., where people are helped to work, to play, to live. (FYI: Edwin Martin, a frequent contributor to this site, was a long-time leader of the Viscardi Center and is a pioneer of services for the disabled; his wife Peggy has been an activist for easing young people into jobs.) Clearly, the Viscardi Center attracts good people. Once a year or so, Pascucci would invite his old teammate to visit the center. “They had a celebrity night,” Paul Nuzzolese recalled Friday, “They’d get athletes like Jack Nicklaus, Gale Sayers, Mike Schmidt, signing autographs. I saw Jim Brown get down on his knees and talk to those kids, and he would say how proud he was to be there.”  Jim Brown never lost his dedication to causes. I ran into him in the ‘90s, at some gathering in the city, I cannot remember the cause – health care and support for broken old football players, or racial causes. Whatever. Jim Brown was wearing a fez over his rugged skull, displaying a familiar hard look below the fez. Omigosh. I felt we were back in the late 60’s maybe in People’s Park in Berkeley, maybe outside Madison Square Garden or some other place that needed an attitude adjustment. The old days were back: Harry Edwards. Bill Russell. Roberto Clemente or Curt Flood giving writers a seminar in the clubhouse. Richie Havens. Nina Simone. Protest songs. The hallowed John Lewis. I saw a puzzled look on the face of a Black journalist, half my age, and I kind of giggled. Jim Brown’s scowl made me feel young again. And on the Manhasset-Port Washington peninsula, the earth still shudders from the powerful athlete who once played here. When Jim Brown returned to his old high school last week, everybody had stories about how he dominated five different sports.

I also learned something about a friend of mine, the late Dick Schaap. Somehow, I had never known Dick played lacrosse – against Jim Brown – when Dick was at Cornell and Brown was at Syracuse. Back in the day, Cornell used to compete with its upstate neighbor in many sports. I did know that. The lacrosse history was in Dick’s autobiography which came out before he died at the end of 2001, but either I skipped over it, or forgot. I thought of Dick as a great and gregarious journalist, who knew everybody, and threw great Super Bowl parties, but I never knew of this bond between two Long Island guys, Schaap from Freeport and Brown from Manhasset. Now I know they played against each other on May 18, 1955. Brown was a sophomore star in football and basketball, and was building his legend as the greatest lacrosse player ever. Dick was the goalkeeper for Cornell, wearing No. 21. He later claimed Brown fired a dozen or more goals past him, one of which he actually saw. But the Cornell Chronicle set the record straight in its tribute to Dick when he passed: “Probably the most notable lacrosse game during Schaap's athletic career was on May 18, 1955. Syracuse barely beat Cornell, 13-12, scoring the winning goal with about a minute left in double overtime. Syracuse's Jim Brown, who would later become a National Football League legend, scored four goals against Schaap, who made 20 saves in that game.” Schaap liked to play up the terror he felt at seeing Brown in a lacrosse uniform. That may have been the same day that Cornell’s football coach, Lefty James, saw Brown jog out to play lacrosse, and said something to the effect of, ''Oh my goodness, they let him play with a stick?'' The fact that Schaap was a jock before he was a celebrity made me enjoy a photo, entitled Three Great Cornell Goalies. Dick is on the left. Ken Dryden who helped win a national hockey championship with Cornell in 1967 and six Stanley Cups with the Montreal Canadiens, is in the middle. And Bob Rule, who won the first official N.C.A.A. lacrosse title with Cornell in 1971, is on the right. Rule was also a backup goalie on the Cornell hockey team that won the national title in 1970, which, according to Arthur Kaminsky, another member of the Cornell tribe, makes Rule the only athlete to win N.C.A.A. titles in two team sports. And Dick Schaap almost beat Jim Brown. (Some of these details were verified by another Cornell guy, Jeremy Schaap, the terrific ESPN journalist, Dick’s son, who notes that his dad was named second team All-East as a senior.) Dick had such regard for Brown that he would not participate in the Heisman Trophy voting for decades because Brown had been passed over for the Heisman after his senior year at Syracuse. As the saying goes, learn something every day. . * * * Two more things about Jim Brown: My friend and neighbor Paul Nuzzolese played baseball against Brown when Paul was a sophomore in nearby Port Washington. Paul thinks he struck out Brown (“That was the least of his sports.”) Paul was out of the game when Brown scored on a Mookie-esque dribbler. The first baseman backed away from contact with Brown and a throw went past him. Brown kept going and was sliding into third base, but the third baseman sidestepped him and the ball zipped past, and Brown raced home. Under-standable, Nuzzolese said, considering everybody had seen Brown run over people during the football season. Nuzzolese recently saw Brown visit the Henry Viscardi School in Albertson, N.Y., which does such great work with severely disabled students. (Brown’s old Manhasset teammate, Michael Pascucci, is involved with the school.) Nuzzolese said Brown could not have been nicer with the students, talking with them, up close and personal. In old age, when he comes home, Jim Brown adds to his legend. |

Categories

All

|