|

When I covered Appalachia from a home base in Louisville, some of the grand leaders of Appalachia had a suggestion for me: why not live in Whitesburg, the center of the universe?

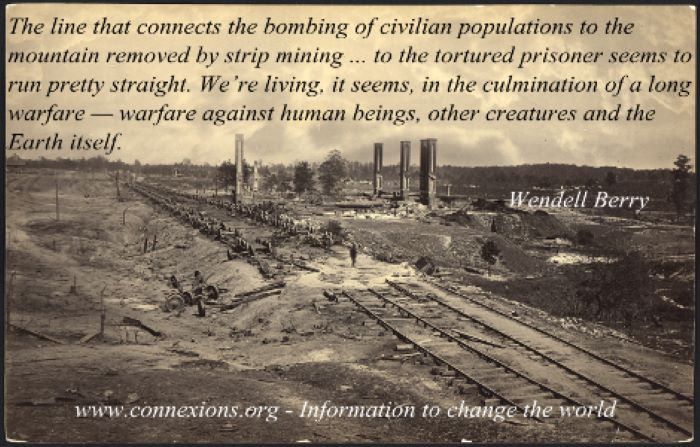

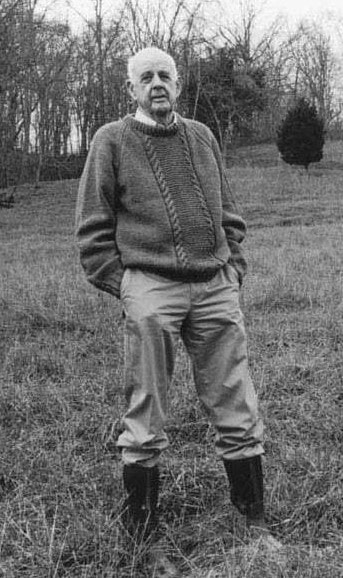

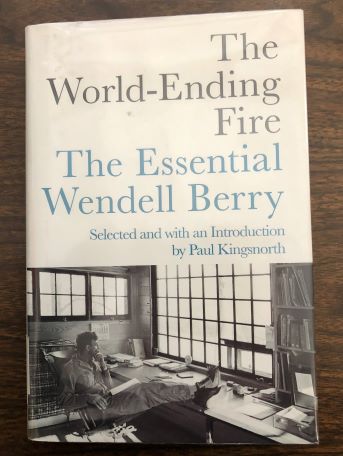

They had a point – “they” being Harry Caudill, lawyer and writer, and Tom and Pat Gish, who put out the great weekly newspaper, The Mountain Eagle (“It Screams.”) Those grand figures of the Kentucky mountains both lived in Whitesburg, in Letcher County, current population 2,200. Also in Whitesburg was Appalshop an invaluable repository of the images and words and sounds of mountain people, mountain culture, mountain history. (See Randolph Fiery's tribute to Appalshop, Comment No. 9.) Now Whitesburg, and Appalachian history, have been crushed by the floods that have marauded through Eastern Kentucky in the past week. The floods have spread mud over every inch of the treasures of Appalshop. I am sick. Here's the NYT article. Fifty years ago, that might have been me writing it. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/04/us/kentucky-flood-appalshop-archives.html?searchResultPosition=1 I have already written about the stricken counties and given three general funds. (below) How can I tell anybody to prioritize a center of history against hospitals and food drives and housing centers? I only know that Appalshop is special, representative of the world that is being washed away because most elected public officials and industry (Here’s looking at you, Commodore Manchin) pay no attention to the region they helped dig up. Here’s a link for Appalshop. https://appalshop.org/news/appalachian-flood-support-resources Now back to our previous disasters: *** In my first month on a new job covering Appalachia, I happened to be nearby when the mine blew up on Dec. 30, 1970. I drove until I found the narrow road leading to the site where 38 miners had been killed in the dog-hole Finley mine at Hyden, Ky. Around 8 or 9 PM, I noticed a Red Cross truck, with long lines, and I waited my turn for, as I recall, a cheese sandwich and a coffee, for which I was extremely grateful. The Red Cross was there at other disasters, like the one at Buffalo Creek, W. Va., on Feb. 26, 1972. People have to eat, in all those isolated towns, most of them on bottom land, inundated by the downpour and the disintegrated hillsides of Appalachia. In the latest horror story, good people and good organizations, are feeding the flooded mountain hamlets of Eastern Kentucky. The Red Cross is there, because it always is. https://www.redcross.org/donate/disaster-relief.html/?cid=disaster_brand&med=cpc&source=google&scode=RSG00000E017&gclid=CjwKCAjwlqOXBhBqEiwA-hhitORr5j455Wf9c-eU79JiSEfjnvHknssybFb8oyhktMRnu0So8boHfxoC4qkQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds Kentucky is lucky enough to have a thinking, feeling governor named Andy Beshear. Only last December, a tornado hit Western Ky, and he set up a special relief mission. This week Gov, Beshear set up another relief mission in the eastern part of the state: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-to-help-flood-victims-in-kentucky Also present is the World Central Kitchen, run by the Washington, D.C. chef, José Andrés. It seems he is everywhere – most recently in Ukraine – and I am not surprised that within hours workers and volunteers were somehow getting to the inundated towns, preparing hot food, good food. https://wck.org/en-us/news/kentucky-flooding I would urge a contribution to any of these funds. I take this disaster personally because this flood has brought up the same towns (Hazard, Troublesome Creek, Isom, Viper, Cutshin, Fisty…) and the same family names I saw on mailboxes in clusters along the highway (Amburgey, Webb, Sturgill, Stamper, Estep). Death and disaster introduced me to Appalachia, and now death and disaster focus my attention, again. The climate continues to grow worse and so have the senators from Kentucky -- people like Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul. Neighboring West Virginia has the coal-dealer, Commodore Joe Manchin, doing something for the good of others only when it profits him. (The Senate? Have you seen the list of 41 Republican scoundrels who have banded together to deprive military veterans of medical benefits for a burn-pit plague?) So what chance do regular Appalachia people have, trying to survive alongside the creeks and rivers in the region known as the “dark and bloody ground” to the Shawnees and Cherokees who were there before Daniel Boone and his kind. Appalachia has been messed over by government and by industry. The least we can do for the flooded people of Kentucky is help feed them. One of my main regrets from my long association with the Commonwealth of Kentucky is that I have never met Wendell Berry. He was already a name in the papers – the poet who wrote with a pen or pencil, the agrarian who warned against forgetting the old ways of farming. He is still at it, age 87, somehow surviving without a computer or television, on his land in Port Royal, and still publishing whenever he feels like it. Finally, finally, with fires raging and tornados rampaging and strip-mine detritus floating past his farm on the Kentucky River, I picked up one of Berry’s most recent books, “The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry,” Selected and with an Introduction by Paul Kingsnorth, published by Counterpoint Press in 2017. Well, never too late – at least to read and honor Wendell Berry, if not to act on his warnings. Those issues were already out there from 1970-72, when my family moved to Kentucky for the Times, for me to cover Appalachia, and, as my wife puts it, “George lived in Harlan and I lived in Louisville.” Certainly, I covered what Wendell Berry preached – the damage from gouging coal from the fragile surface of the Cumberland Mountains; the need to farm intelligently and personally, not by corporation; the sellout by politicians who scorned the land for their own profit. (See: Manchin, Joe, a/k/a Blind Trust Joe, Commodore Manchin, and Worse.) But why didn’t I try to flash my NYT credentials and try to arrange an interview with Wendell Berry and his wife-partner-fellow-agrarian Tanya Berry? Goodness knows, I got around Kentucky. I met Harry Caudill, whose book “Night Comes to the Cumberland” made me want to go to Appalachia, to write about it. I got an epic private tour of Gethsemani Abbey outside Bardstown, and met the monk-colleagues of Thomas Merton, a few years after he died in 1968. I visited Pauline Tabor, the famed madam of Bowling Green, Ky., at her tasteful home with her majolica collection. I went campaigning with Happy Chandler on his nostalgia-trip final campaign. I got to know the McLain Family Band out of Berea. I also met Jean Ritchie, originally from Viper, Ky., the personification of Kentucky folk music, who also lived in our home town on Long Island. In Louisville, we lived next door to Rabbi Martin Perley, brave civil rights advocate, and his wife, Maie Perley, a writer. And I depended on the superb journalism of the weekly paper, The Mountain Eagle ("It Screams!") in Whitesburg, bravely issued by Tom and Pat Gish. And I interviewed Sen. John Sherman Cooper when he announced his retirement (in an era when Kentucky Republican senators were not necressarily vile.) Oh, yes, and I interviewed Loretta Webb Lynn of Butcher Holler, Ky., on the morning after she won country music’s Entertainer of the Year in 1971, and we stayed in touch. So you tell me: why didn’t I try to meet Wendell Berry?  His words and messages are very much out there. My Appalachian “correspondent,” Randolph Fiery, originally from West Virginia, often cites Berry as a spiritual and ecological inspiration, so I took out the book from the great Nassau County library system. Berry had me in the first pages of the first selection, “A Native Hill,” written in 1968 – in which he describes his odyssey in his 20s from academic and writer in the great cities to return to the land, owned by his family for six or seven generations. He follows the trickle of water toward the larger streams below: “As the hollow deepens into the hill, before it has yet entered the woods the grassy crease becomes a raw gully, and along the steepening slopes on either side. I can see the old scars of erosion, places where the earth is gone, clear to the rock. My people’s errors have become the features of my country.” Berry’s words touch off memories of the first house we bought, out east of Louisville, in an old place called Prospect. Builders had carved a freaking golf course into the plateau and our new house sat on the western edge, facing undulating plains – including a family cemetery. (The realtor promised us there would be no further development.) A trail led downhill, following the trickles, toward Harrod’s Creek. I loved walking alone in the woods – well, until a few months later a chunk of rock landed on our back lawn, nearly missing our youngest child -- from dynamite by a crew expanding the sub-division. Turned out the real-estate agent had lied, so we moved much closer to town, but my love of the woods remained. Now I recognize the very same flow of land in Berry’s descriptions of his family farm – from utilitarian Indian paths to dirt roads widened by soldiers and now, not far from his home, “its modern descendant known as I-71, and I have no wish to disturb the question of whether or not this road was needed.” I think of how many times I – or my family of five – barreled back and forth along I-71 toward home (New York) or the nearest city with baseball and other urban pleasures, that is, Cincinnati. Turns out, Wendell Berry’s farm – where he still farms and writes – is an hour to the East End of Louisville. But I never tried to interview Berry about ecology or strip mining or the diminution of family farms.  Berry’s beliefs resonate in his articles over the decade. In the chapter “Family Work,” Berry laments the long hours modern children spend cooped up in school: (“why should anyone be surprised if, under these circumstances, children should become ‘disruptive’ or even ‘ineducable’”) And in “Economy and Pleasure,” he describes the joy of taking his 5-year-old grand-daughter out to work the two-horse team in plowing some family land, and how she took to the reins. (I will not divulge her charming comment at the end of this utilitarian joy ride; she addresses her grandfather as “Wendell.” Cool.) For me, the last chapter was the best – “The Rise,” from 1969, as Berry describes a six-mile canoe sojourn down the Kentucky River – in mid-December – when the water was high, bringing him closer to modern life on the shores. The chapter reminds me of times I went out on Harrod’s Creek.with my friend, Dr. Sid Winchell. In "The Rise," Berry takes the reader to the time of the Shawnee and the arrival of Gen. George Rogers Clark to the still peaceful flow of the Kentucky River, even with all the debris floating alongside the canoe. Berry’s long life of farming and writing and loving the land awaken my sensibilities. I already mourn the new “settlers” in our wooded corner of the suburbs, who cannot wait to hack down trees, despite the first aid trees furnish a grievously wounded planet. Wendell Berry has been preaching to us for more than half a century. Long may he write. By pen or pencil, of course. *** (Mea culpa: written on a ThinkPad, using a Word program, issued by the Weebly site, via the Internet.) *** https://berrycenter.org/ Nice article by Silas House in 2020: https://gardenandgun.com/feature/wendell-berry-the-poet-of-place/ A month ago, during reports of turbulent weather on Long Island, I looked out the west side of our house and saw leaves being twirled in a cone shape, by a brute force.

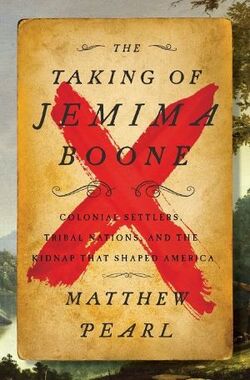

Not long after, three distinct tornados hit ground east of us—a calling card from the future. We are receiving predictions of global warming, but we don’t do enough. Wouldn’t want to upset the federal budget, would we? The weather is getting worse everywhere. One tornado tore through Middle America on Friday, killing hundreds, tearing up Mayfield, in western Kentucky. The destruction touched home with me, coming at this time of year, when darkness falls early, and people try to light up the night with holiday decorations. A December tragedy reminds me of 1970, when a mine blew up in eastern Kentucky, killing 38 miners one day before New Year’s Eve, and as a regional news reporter for the NYT, I happened to be in the area, and rushed to the scene of the disaster. Whenever something like this happens nowadays, I think I have a journalist’s version of PTSD, viscerally recalling the gloom of long nights, people gathering, at the mine, at the funeral parlor, at the little country churches. My family got to know Tornado Alley from 1970 to 1972, when we lived in Louisville, getting acclimated to another part of the world, including its weather. My wife knew about tornados. She had lived just west of Dallas as a kid and remembered what people did when they saw funnel clouds. If the car radio brought tornado watches, and the sky looked ominous, she would pull off the road and look for the lowest dip in the ground. One day, I had to rush to a town about an hour southeast of us, where a tornado had struck without warning, killing a little boy who been sleeping upstairs – blowing him into the branches of a tree just outside his window. By the time I got there, it was a lovely morning. Tornados are lethal. My wife kept saying one was going to come blasting up the Ohio River, to the sweet little suburb where we lived. On April 3, 1974, about 18 months after we chose to move back home to Long Island, a tornado came right up Brownsboro Rd., blowing down the garden apartments at the corner, taking off the roof of the school our two girls had attended. That same tornado soon decimated Xenia, in Ohio, to the north, killing 38 and dislodging thousands. My wife had called the 1974 tornado, just as she heard about a virus on the loose early in 2020, and predicted the pandemic that will not abate, given the arrogant people who will not get vaccinated. Now we have Mayfield, essentially leveled to the ground, and parts of six states grievously broken. What can we do? Our so-called leaders, political and commercial, hear the science of global warming, but they cannot move as fast as a tornado, roaring across the countryside. The best we can do right now is give some money, to care for the current victims. The Commonwealth of Kentucky, wisely led by Gov. Andy Beshear (whose grandparents’ house is in stricken Mayfield) has a disaster fund: https://secure.kentucky.gov/formservices/Finance/WKYRelief And, thank goodness, there is always the Red Cross, on the site, in minutes. (I remember the Red Cross quickly at the scene in 1970, passing out sandwiches and blankets and first aid outside the Hyden mine.) https://www.redcross.org/donate/donation.html  As soon as the final out settled in Freddie Freeman’s glove, I felt a surge – not quite the relief I felt when the Covid vaccine arrived in my arm but rather the excitement of a great swath of free time, suddenly arriving. Book time. I wasn’t reading hard-covered books during the warm months, but I kept taking notes about books I wanted to read. Now, no more long evenings obsessively watching the hapless Mets organization fall apart, in the person of Jacob deGrom’s pitching arm. Now, World Series over, free at last. The first book has been “The Taking of Jemima Boone,” by Matthew Pearl, about the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s most spirited child, on July 14, 1776. I was drawn to the subject because Daniel Boone was all over Kentucky when I lived in Louisville for two years, as the Appalachian news correspondent for the NYT, wandering the region. Boone's statue and name were all over the Commonwealth of Kentucky, as I drove on twisting roads that had been paths for him to explore, to hunt, to escape. But somehow I never wrote about him in all the time I roamed around Kentucky. Now Matthew Pearl, a novelist by trade, has written a taut drama, with a thick index in the back, assuring me that he was using source material and not only his novelist’s imagination. It’s a tricky time to be catching up on an American icon, most known for barging into Native American territory, often fighting for land, as well as for his life. The U.S. is re-evaluating its memorials to slave-owning Confederate generals, as well as explorers like Columbus. What to do about Daniel Boone? The reason Jemima Boone and two other girls in their early teens became prisoners is that Daniel Boone could not, would not, stay in coastal towns but pushed west through the Cumberland Gap and on, losing a son, driven by a tropism for space and land and “freedom.” This American icon was taking other people’s land -- at gunpoint – but his relationship to the people of the land was more complicated than that. He became part “Indian” in style and spirit. He was captured by a complex chief, Blackfish, who adopted Boone as a son, and recognized him as a kindred soul, with skills and courage. Boone, of course, was planning his escape. The actual “taking of Jemima Boone” occupies the taut first 75 pages of this book – how she tried to fight off the men who surrounded their canoe, how she left signals for the man she knew would come looking for her, and how she bonded, in a way, with the son of Blackfish, who treated her with respect, by all versions. Pearl, the novelist, resists going too far in suggesting a romance between captor and captive. In fact, one of the things I have learned from recent reading about New England settlement is that Indian males almost never raped, although some did “marry” their captives. It never came to that in this Kentucky encounter, but the details seem to have survived (with revisions, with exaggerations, surely) into the 19th Century, and then the 20th, and now the 21st. Matthew Pearl makes it real. Daniel Boone kept going, all the way to Missouri, where he and his wife Rebecca and Jemima Boone all died – of old age. He has two graves, one in Missouri, one in Frankfort, the Kentucky capitol. I recommend “The Taking of Jemima Boone” as a well-written and well-researched visit to a distant time, leaving complexities in a nation now re-examining (at long last) its myths and heroes.  I rarely read fiction these days; so much to learn from non-fiction. In spurts of reading, I have belatedly learned about Neanderthals and evolution and DNA, as well as the earliest “settlers” of New England. This has been spurred by my wife’s vast personal research in the genealogy of her family, from England and Scotland. Next in my reading list: “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” by David Hackett Fischer I was drawn to the book by a review by Joe Klein in The New York Times, with this overview: “Albion’s Seed” makes the brazen case that the tangled roots of America’s restless and contentious spirit can be found in the interplay of the distinctive societies and value systems brought by the British emigrations — the Puritans from East Anglia to New England; the Cavaliers (and their indentured servants) from Sussex and Wessex to Virginia; the Quakers from north-central England to the Delaware River valley; and the Scots-Irish from the borderlands to the Southern hill country. I consulted the index and found this one reference: “When backcountrymen moved west in search of that condition of natural freedom which Daniel Boone called ‘elbow room…’” Do these four separate waves of emigration explain why the United States, perhaps more than ever, seems to be several different countries, with rival impulses and outlooks? Does it explain Red and Blue states or regions? I look forward to learning what Fischer has to say.

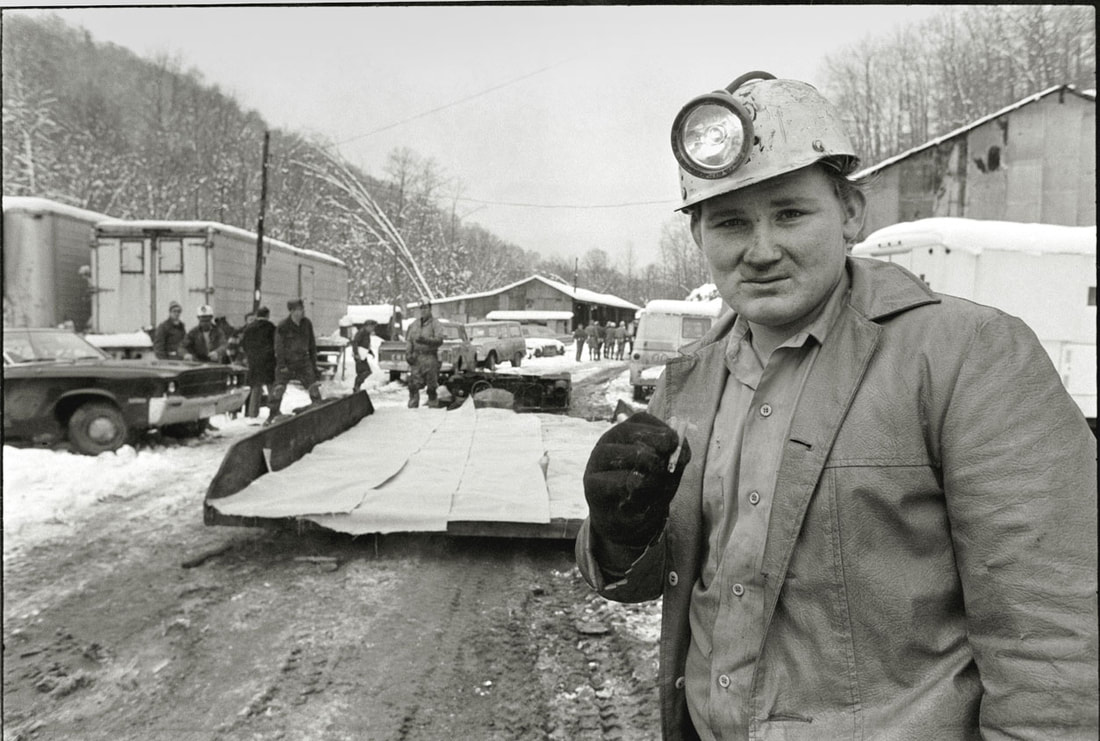

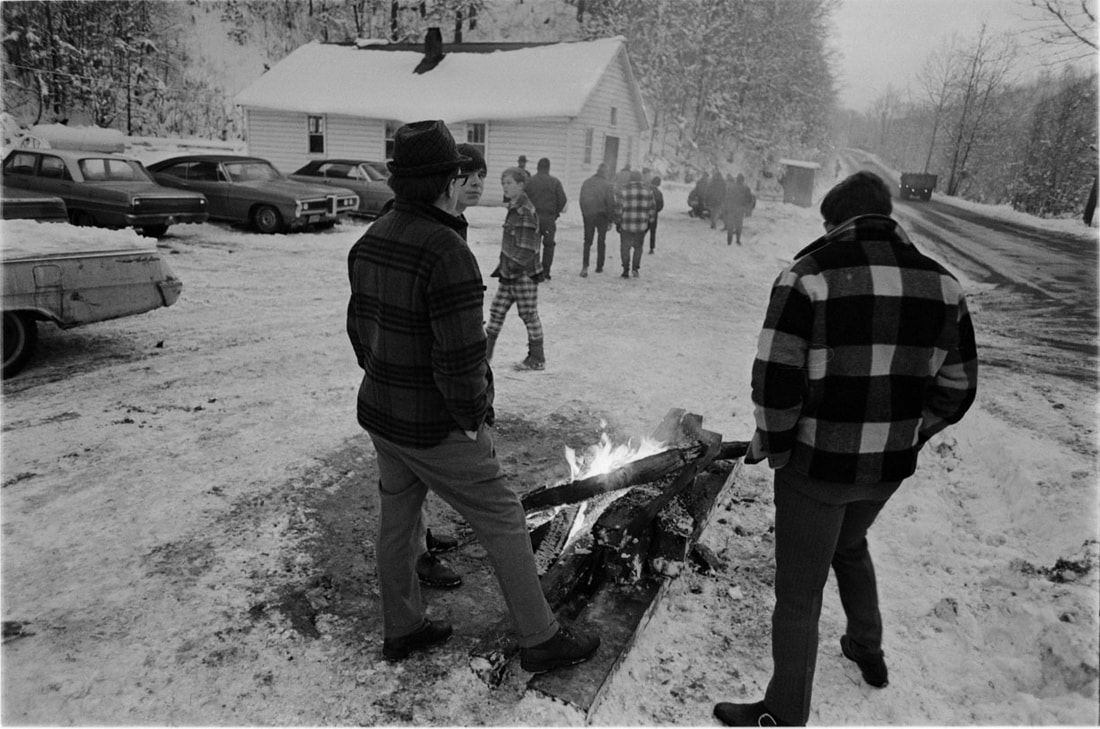

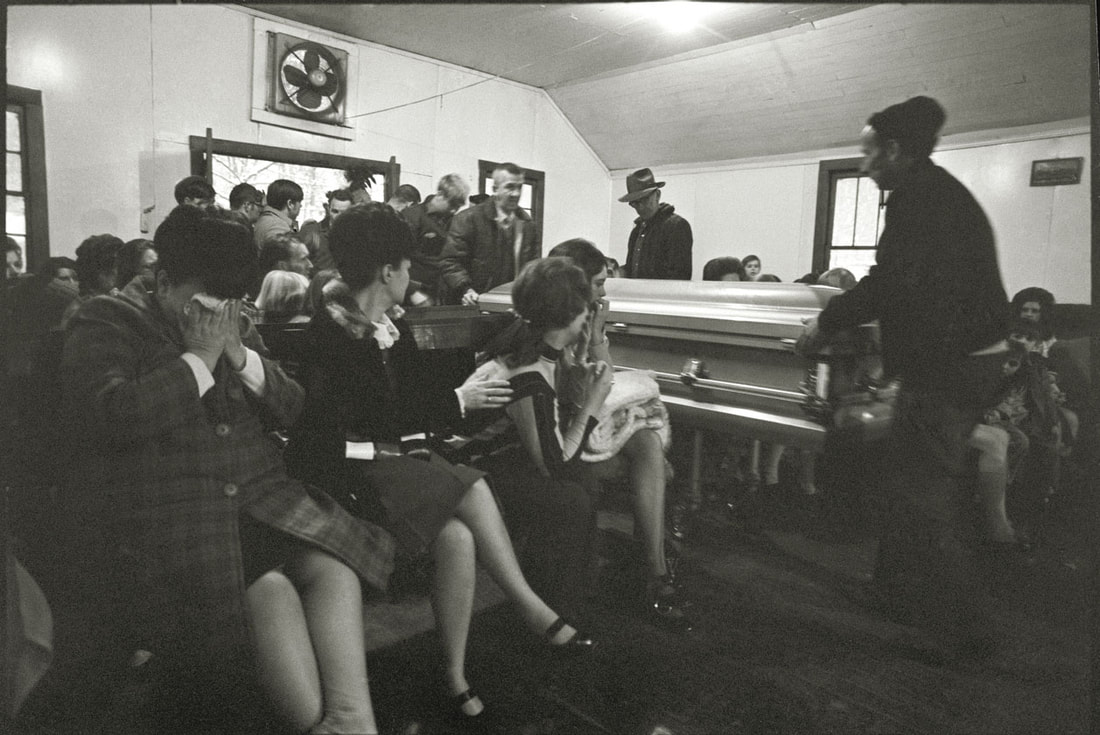

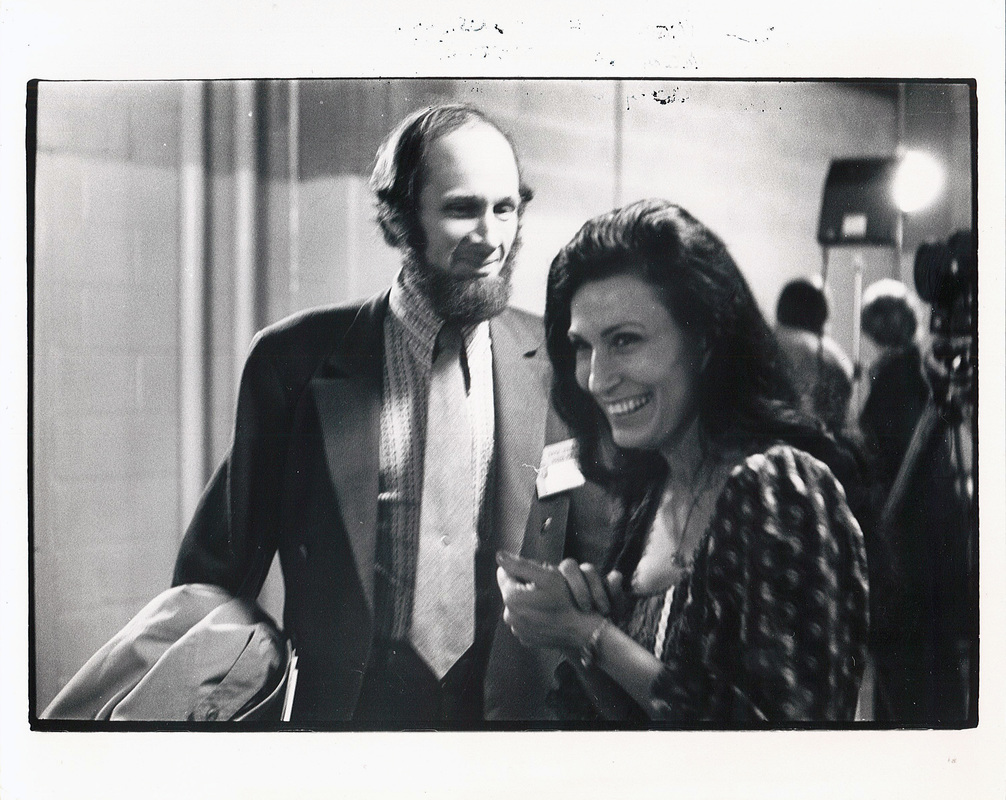

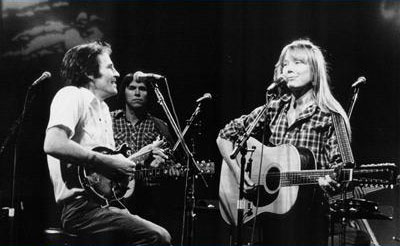

Tom T Hall passed on Friday, He was a country songwriter who informed my work, telling stories about people. He observed every-day life, regular people, and made them real, with a large dollop of insight and sympathy and wit. I read the lovely obituary in the Sunday NYT by Bill Friskics-Warren and I tried to remember when I first heard Tom T Hall. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/21/arts/music/tom-t-hall-country-musics-storyteller-is-dead-at-85.html I think it was after I had been one of the first reporters on the scene for the terrible mine explosion in Hyden, Ky., on Dec. 30, 1970. I came back many times, met a lot of survivors – “the widders,” as they say. Turned out, Tom T. Hall was there soon after. He and a buddy drove a pickup from his home in Olive Hill, Ky., not far from the coal region, and he observed with a storyteller’s eye, including the sheriff and the undertaker whom I had met. Maybe he had read my stories, maybe not. Didn’t matter. He put it to music, got it perfect. (The “pretty lady from the Grand Ole Opry” is Loretta Lynn, who had come off the road to play a charity concert in Louisville in 1971, for the survivors. That’s how I got to know Loretta, and later helped her write her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.”) In the next years, I collected cassettes of Tom T Hall’s best albums and songs and would play them as I drove around Appalachia. . Some of his best songs were about lost or unrequited love: “Tulsa Telephone Book” -- Readin' that Tulsa telephone book, can drive a guy insane Especially if that girl you're lookin' for has no last name. “The Little Lady Preacher” -- (A picker remembers the gospel singer he backed up every Sunday morning: “She’d punctuate the prophecies with movements of her hips.”) We never met, but I took my young family to see him in New York in the mid-70s. I learned that he had settled in the lush outskirts of Nashville with his wife, Miss Dixie, herself a fixture in Music City, who passed a few years back. I owe Tom T Hall a great debt because he helped me recognize the best parts of people, as flawed as we all are. Only he put it to music and he sang it. In honor of Tom T Hall – a requiem for the older friend who taught him to pick, and other stuff. NEW PHOTOS: My friend Ken Murray, one of the great photographers in Appalachia, has sent photos of the terrible days after the explosion. Please see below. GV. Shadowy figures around a bonfire, silence that screamed of fear. It was Dec 30, 1970, and people were waiting, waiting for what they already knew. The mine had blown up. This was outside Hyden, a Kentucky town I had never heard of, until the office back in New York said I'd better get there, fast. The next hours are a sad blur to me – a reforming sportswriter on my first month as a news reporter in Appalachia, trying to make sense of a coal-mine explosion. I had taken the job offer from Gene Roberts, the legendary national editor at the NYT, and my wife and three small children had just moved to Louisville. On the next-to-last day of 1970 I drove down the Mountain Parkway for a feel-good, get-acquainted story, my first from the Appalachian Mountains. After a few hours, I decided to call the office before heading back to Louisville. The office told me a mine had blown up about an hour to the east, so I took off. I found the mine and saw a woman walking on the chewed-up dirt road. I stopped my car and opened the passenger door and she got in. We did not say a word. Her fear was palpable, as if she were thinking, "I am now a widow." I let her out near the crowd outside the mine office. When I parked my car, I realized she had left a pair of gloves and a can of cat food. The troopers herded reporters behind barriers so we would not intrude on families, but reporters always find ways. The one thing we knew was that there had been an explosion on the day shift at the Finley mine at Hurricane Creek. As darkness fell, we knew that 39 miners had been in the drift mine – a horizonal opening into an Appalachian slope. One miner had been blown clear of the mine mouth and was alive; the rest were inside, and we pretty much got the point. Family members clustered together, as if forming a protective huddle against outsiders. It felt like one of Goya's haunting "Disasters of War," on which he wrote: "This I have seen." Gov. Louis Nunn arrived and informed the reporters that this is the kind of thing that happens once in a while in coal mining. Then he got on the helicopter and headed back to Frankfort. Somehow, I scribbled a rudimentary story in my notepad and waited my turn for the one telephone on the mine wall. A trooper guarding the phone got itchy about my taking up time but I fended him off with shrugs and hand signals, and he let me finish. (I asked the office to call my wife and say I would not be home that night.) The warm spell ended abruptly, and snow began to fall – a desolate scene, lit by bonfires. The Red Cross was giving sandwiches and drink to everybody. My very supportive colleague in the Washington bureau, Ben Franklin, using his vast sources, dug up news that the non-union, "dog-hole" mine had been open less than a year with numerous citations but no major penalties or shutdowns. I needed a place to stay that night, and Dr. Tim Lee Carter, who represented the district in Congress, suggested a motel just north of Harlan – “ a short ride from here,” he said. Turned out to be 34 miles – 51 minutes, much longer in a snowstorm. I made it up the hill to the motel and got a room but of course had no clothing, no shaving kit, no change of shoes. I was alive. I made some phone calls and went to sleep. The next morning, there was nearly a foot of snow on Pine Mountain. Heart in my mouth, I told myself that I was now a New York Times news reporter and I needed to get back to the story. My car did not have snow tires. I tried to gun it uphill but the car spun out, onto the shoulder – a good thing, since the other side of the road was facing downhill. Nobody without four-wheel drive and chains was going over Pine Mountain that day, so I worked the story via the motel phone, and bought a fresh shirt from a trucker who was also stranded and spent New Year’s Eve watching the snow fall. On New Year’s Day, reinforced with snow tires, I made it over Pine Mountain and back to the mine, still feeling very much like an outsider. The sun was out, and reporters waited for more details. The county judge – the top elected official in Kentucky counties – a sturdy guy named George Wooton -- was crouched over a bonfire, frying “coal-miner steaks” – bologna. The owner of a neighboring mine was giving his opinion of what caused the explosion – words to the effect that “those miners made a big mistake.” In one sequence, Judge Wooton calmly laid the frying pan alongside the fire, stood up, and with one swift punch, he cold-cocked the talkative mine owner, who was out for a few minutes, before slinking away, while Judge Wooton resumed frying bologna. (I found out the other day that Wooton had served under Patton during WW II; tough old guy lived to be 94.) The next day, Ken Murray and I attended the first funeral for any of the miners, attended by other miners. Nobody was talking much, there was an air of let’s-get-it-done. I didn’t understand at the time, but later learned that the first man buried had been the “shot man” in the mine – the one who detonated the explosives. In the days and months ahead, I covered hearings in Washington or Kentucky and watched Finley miners smirk and swagger as they testified they knew nothing, nothing, about the explosion. It turned out that the “shot man” had regularly used the fast-working but dangerous primer cord, an outdoor device that was unsafe inside a mine, with its methane-gas deposits and live sparks – particularly in certain barometric conditions, like a warm day in December, with a snowstorm on the way. The understanding of the dangers, the violation of law and common sense, was part of the ethic of miners. Mining was the best way to make a living in isolated Eastern Kentucky. In pillow talk, miners sometimes told their wives or girlfriends what was going at the mine, but other times they practiced a miner version of omertà. I loved this part of my job, speaking up for Appalachia, whose coal was used to heat and cool much of the country, after the rubble had been dumped in the narrow valleys. (Even now, fools like Donald Trump blather about reviving the coal mines; the miners know better.) In the days and months ahead, I returned to Hyden for hearings, interviewing some of the widows, like Edith Harris, smart and outspoken, who said the “rich widows” were, in a perverse way, envied for the insurance money they received. For months afterward, the gloves and can of cat food from the woman on the mine road remained in my car; I could not bear to touch them. To this day, when I think of the bonfires and the silent suffering in the wintry darkness, the very name “Hyden” gives me the shivers. * * * --- A few months after the mine blew up, I ran into Judge Wooton in a coffee shop on the Mountain Parkway, and he raved about Loretta Lynn, who had come off the road to give a benefit for the miners’ families. I made a mental note to write about her for the NYT – which ultimately led to my helping Loretta write her book, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” * * * ---After the Hyden nightmare, as long as I worked as a roving reporter, I kept a bag in my car trunk, with clothes and a shaving kit and warm shoes. -- (some of my articles) https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/31/archives/toll-of-39-feared-in-mine-explosion-bodies-of-15-are-recovered-from.html https://www.nytimes.com/1971/03/13/archives/miners-fears-recalled-in-testimony-of-widows.html https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/20/archives/kentucky-communitys-scars-visible-a-year-after-mine-disaster.html * * * ---Wonderful recent photo spread in the Courier-Journal: https://www.courier-journal.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2020/12/23/hyden-kentucky-mine-disaster-photos-then-and-now/3939417001/ * * * --Kentucky-born Tom T. Hall – “The Storyteller," whose work I admire -- visited Hyden early in 1971 and wrote a song about the disaster: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k3Gmlp7PeDw Some lady said, "They's worth more money now than when they's a-livin'. " And I'll leave it there 'cause I suppose she told it pretty well Kenneth Murray and I met at the Hyden mine, went to some funerals and press conferences and became friends for life. Ken has worked for newspapers in the Tri-Cities area of Virginia/Tennessee and has roamed the area, with an eye for the old ways that are still with us His books and artful photographs are easily found on line. These photos give a sense of those grim days.

Now that our Dear Leader is back on his meds, the United States is in the hands of Mitch McConnell.

Yikes. This was the conclusion in the past day as we realized the world was not in smoldering ruins, not yet, from an impulsive drive-by shooting ordered by the Dear Leader. The twitchy fingers of Twitter America have produced a theory that somebody had fed him doggie downers or whatever it took to leave Donald Trump slurring as he mechanically tried to read what his handlers had written for him. Not a pretty sight, but better than more rabid postures he takes. Meantime, the nation is back in the hands of the same friendly feller who kidnapped the Supreme Court candidacy of Judge Merrick B. Garland and committed other acts of contempt toward democracy. I don’t need to go through the scenarios of the impeachment frolics. We’ve got time to talk about it while Nancy Pelosi – the smartest person in the room – is making the Dear Leader twist. But I, who lived in Kentucky as a Times reporter for a few years and returned often, have my own take on Mitch. I have told this story before. Short version: I covered a statewide election in Kentucky and the winning candidate – I have no memory which one or which party – celebrated that night at headquarters by proclaiming: “They’ve had their turn at the trough; now it’s our turn.” Ever since then, I retain the image of one porker or another making the most of his chance – no concern for others. Millions of Americans would not have health care, however imperfect, if John McCain had not pointed his thumb downward on that historic midnight. Mitch would be fine with disregarding the needs of the poor in the cities and hollers of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He also shows his contempt for others by championing the dying industry of coal mining, which I covered years ago. He doesn’t care how badly King Coal pollutes the land and the air – or that it is is only a sliver of Kentucky’s economy. His turn at the trough. McConnell’s posture is even more negative considering that he broke into politics as an aide to Sen. John Sherman Cooper, a Republican – I guess you’d say an old-style Republican. Cooper was worldly and collegial. I covered his announcement that he would not run again in 1972. Maybe I met McConnell that day; I do remember the gravitas of John Sherman Cooper. I think of Cooper and others these days during the scrimmage for the House-to-Senate impeachment. I remember when Democrats like Sam Ervin and Republicans like Howard Baker were able to work together in the Watergate scandal that doomed Richard M. Nixon. It seems clear to me – from the impulsive assassination ordered by Trump to the lies from Trump’s toadies, angering even a Republican stalwart like Mike Lee of Utah – that the United States needs Trump dismissed. Mitch McConnell is trying to block it. I don’t know what McConnell gains from a defective president like Trump. But it’s still Mitch’s turn at the trough, and that may be all that matters to him. * * * Here is Gail Collins today, on McConnell. (I have delayed my pleasure in reading Collins until after I file my little screed, which was already in the works.) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/08/opinion/mitch-mcconnell-trump.html It took a lovely post by a friend to remind me that Mardi Gras is about to morph into Ash Wednesday.

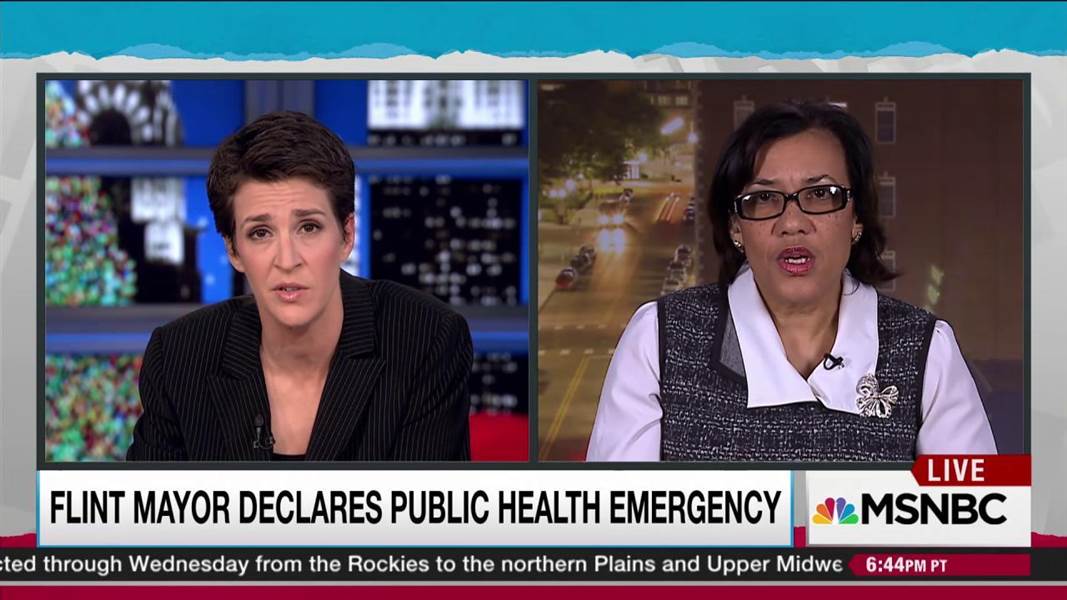

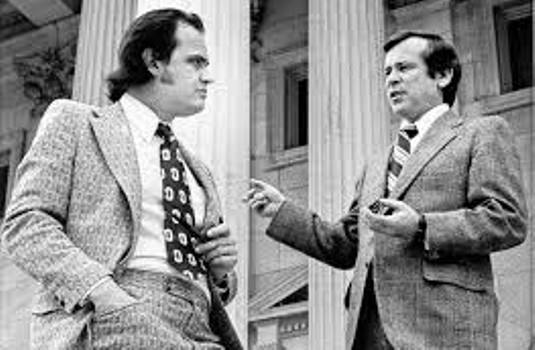

Bill Lucey, a writer and editor in Cleveland, puts out a thoughtful website about (a) baseball, (b) journalism, and (c) life itself. His post today is about how he should observe Lent this year. His examination of his faith should be read on its own, not in my paraphrasing: https://www.dailynewsgems.com/2019/03/the-meaning-of-giving-up-for-lent.html Lucey's article prompted me to recall Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday from my own perspective, having been raised (and raised well) as a Roman Catholic. I know my two sisters and their families will be observing Lent. (We took two close relatives to our beloved Mama’s in Corona a few years back –during Lent -- and they had to pass up some of the glories of deli and pastry. Oy. That is faith.) Today’s post by my colleague prompted two memories: 1. As the oldest of five, I was fortunate to walk to church on some weekdays with my Irish-born grandmother, always in black. Sometimes she would take me to a luncheonette on Jamaica Ave., for breakfast after church – but maybe not during Lent. I don’t remember. (Kids, ask questions of your grandparents…and your parents. Get their views, their histories.) 2. My most vivid memory of Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday is from 1971, when I was a news reporter for the NYT, based in Louisville. I had just covered my first coal-mine disaster, in Hyden, Ky., and was still reporting on it. On Feb. 23, however, I was in central Tennessee, covering a story on an army base. I had no clue about Mardi Gras until I had to wake up before dawn to drive across to a hearing in Eastern Kentucky. Barreling due east on the interstate, I messed with the radio dial (much more fun in the pre-digital age) and found a lively station – WWL, New Orleans, 50,000-watts. This post began as a memory of Lent, a spiritual journey, but somehow it is turning into a tribute to the great clear-channel stations of North America – the ones that would keep you going on cross-country drives. (Grand Ole Opry on Long Island on Saturday nights; one Phillies-Cardinals thriller all the way out to Chicago.) https://www.radiodiscussions.com/showthread.php?617480-50-000-Watt-Stations-on-North-American-Clear-Channel-Frequencies This time, pre-dawn on Feb. 24, 1971, I listened to the overnight DJ on WWL raving about Mardi Gras, which was slowly winding down on the littered and sodden streets of New Orleans. He talked about the beads, the drinks, the costumes, the food, the pretty women, the people leaning off their elegant balconies in the French Quarter, shouting and personifying the slogan: “Laissez les Bon Temps Rouler!” And there I was, in the dark, on I-40, heading to a hearing about poverty and neglect in Appalachia, taking in reports of the last bursts of sensuality in New Orleans. Mardi Gras turning into Ash Wednesday, mile by mile. That was Mardi Gras/Ash Wednesday, 1971. Now, stirred by Bill Lucey in Cleveland, I have to figure some way to honor Lent. Thanks, man. Nice to be back in the NYT, twice in one day – courtesy of two hard hitters, Gordie Howe and Muhammad Ali. The Times resurrected a column I did in 1996, the morning after Ali’s stunning appearance, carrying the Olympic torch. Then by coincidence, they also used a column I prepared a year ago, when Gordie Howe had a stroke. Two great athletes in vastly different sports, one expanding his strong personality over the years, the other subordinating himself to his sport and his home of Canada. * * * Some thoughts on the farewell to Ali: I was asked to provide some color for the funeral for the lively New York television station, NY1, which, alas, I cannot access on Long Island due to cable rivalries. I spent a pleasant afternoon with Roma Torre, the anchor (and daughter of epic New York Herald Tribune journalist Marie Torre.) She let me share some of my glimpses of Ali, in Louisville, where I lived for a few years, and at boxing events. In between, we watched the farewell to Ali. It was fascinating to see Ali as touchstone for the religions and passions and politics of so many disparate people – the activist, Rabbi Michael Lerner of New York, Chief Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Nation (unidentified as a great Syracuse lacrosse player and teammate of another Greatest, Jim Brown), and so many Ali women, with his verbal gifts and his beauty. When I called home, my wife raved about Billy Crystal, for catching Ali (and Howard Cosell) just perfectly, telling how Ali stopped jogging at a swank country club in the New York suburbs after Crystal mentioned that the place was known to exclude Jews. The one over-riding impression of Ali was a man who did righteous things, in small and hidden and often funny ways – in contrast to his public bombast and occasional cruelties. I liked him even better afterward. * * * My column on Ali at the Atlanta Olympics revived my memory of how it came about – as pure afterthought, blessed inspiration, the next morning, on three hours of sleep, when I had committed to covering the first gold medal of the Games, for shooting. My strongest memory is of an Iranian woman in full chador, competing, making it a truly universal Olympics. But as I banged out my column smack on deadline for the first Sunday edition, I realized we (I) needed to get back to what it mean for Ali to materialize like that, high above the stadium, like a comet, glowing brightly. I consulted with our Olympic bureau chief, my pal Kathleen O. McElroy, and we got a short column done for the second edition, and for posterity. How sweet that the NYT would find it again this week (with a photo by the great Doug Mills, now taking photos of President Obama in the White House.) * * * It touched me to see Ali buried in Cave Hill Cemetery, in one of the most beautiful corners of Louisville – steep hills, limestone outcroppings, Beargrass Creek flowing through it, with tombs of many famous Louisvillians – veterans on both sides of that ghastly Civil War, plus George Rogers Clark, Joshua Speed, Barry Bingham Sr. and Barry Junior (who was so hospitable to me in my two-year stint as Appalachian Correspondent for the NYT) and Col. Harland Sanders (whom we once saw eating ice cream one night – in a Howard Johnson’s.) We almost bought a house in that funky old neighborhood of the Highlands – always sorry the deal fell through -- and when I returned for the Derby I would duck the Oaks on Friday and go jogging in the Highlands, including through Cave Hill Cemetery. When it quiets down, I’ll go back and pay respects to Ali. RIP. Thousands of children and adults have been poisoned in Flint, Mich. On Wednesday night in Flint, Rachel Maddow – who has served as a national conscience in this latest tragedy mixing politics and pollution – held a “town-hall” meeting on MSNBC. The meeting provided information and a bit of catharsis for people in Flint -- but no detectable action or shame from the dim-bulb state government that has occupied poor towns in Michigan in recent years. However, Flint is not the only place where poisons have been let loose. More below. This horror in Flint has been coming for years, since Gov. Rick Snyder began appointing unelected “managers” to run some Michigan towns, many of them with large black populations. It looked like the bad old days of South Africa. To save a few bucks, Snyder’s brain trust chose to use water from a polluted river rather than Lake Huron. None of Snyder’s “experts” knew enough to install filters, so lead began showing up in the water – and in children’s bodies. Lately the governor has been standing around, looking a bit stricken, as people passed out donated water bottles, hardly a solution to the health crisis. On Wednesday night we learned that it might cost over $10,000 per house to replace the poisoned lead pipes. No work has started. The state government is now in the position of needing help from a federal government that it has vilified as the enemy -- kind of where we are in this country these days. Maddow has been shining a light on some states with Tea Party and Koch Brother types – North Carolina, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Michigan and Virginia. She reported on Bob McDonnell, then the governor of Virginia, for his fetish for highly personal medical scans of women, labeling him “Governor Ultrasound.” McDonnell and his estranged wife are now appealing prison sentences for corruption while Maddow has moved on to Flint, which badly needed a friend. America is good on polluting itself. The New York Times, in the Jan. 10 issue of its Magazine, ran an absolutely riveting article about how DuPont dumped its refuse in the water table of northern West Virginia for many years. A highly responsible mainstream Cincinnati law firm allowed one of its corporate lawyers to take up – and win -- a pollution case. But with pollution, there are no victories. I recently talked to Mike Glasser, a friend of a friend, who is taking chemo for cancer he believes was incurred while mixing chemicals amounting to Agent Orange. But it was not in Vietnam, where we dumped it willy-nilly. It was at Chanute Air Force Base in eastern Illinois, long closed, with people and animals and lakes and land showing signs of chemical damage. One young reporter, Bob Bajek, took up the issue for a local weekly, and managed to get a highly detailed story published pointing to chemicals used at Chanute more than 40 years ago. Bajek doesn’t work there anymore. One of his superiors said he stirred up trouble, writing things people didn’t like to read. * * * Here are two links by Bob Bajek: His reporting on the pollution: (click link below:) _ and the response to his work: (click link:) _ * * * None of this is new. May I recommend this version of “Black Waters,” performed by Kathy Mattea, from South Charleston, W. Va., as courant as when the great Jean Ritchie of Viper, Ky., wrote it in 1971. Mattea's prelude is worth hearing. Black waters are now flowing in Flint. Fred Thompson’s obituary reminded me of another time and place, when fewer public figures made me feel, well, I think the word is icky. In the very early ‘70’s, I was a New York Times Appalachian correspondent based in Louisville. There were giants in those days, who believed in government. Some of them were Republicans. I got to write about Sen. John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, Mayor Richard Lugar of Indianapolis and a young United States Attorney from Western Pennsylvania, Richard Thornburgh, who gave me a private seminar in jury selection that informs me to this day. One lovely fall day, I took a ride around Nashville with Sen. Howard Baker, who was running for re-election. He brought along his campaign manager, tall and droll, Fred Thompson. I don’t remember a word. My story included Baker’s Democratic opponent saying Baker was too liberal toward the antibusing movement. I only remember good conversations in the car and Fred Thompson’s pipe. For a lefty from New York, I was not at all surprised to see things from their perspective, and to enjoy their company. The Watergate break-in had taken place three months earlier. It was not mentioned in my story. None of us had any way of knowing Baker would be a major figure in the hearings, and that Thompson would become famous for whispering to Baker, as one of his chief assistants. I was not the slightest bit surprised when Baker was seen as a stalwart, honest man who examined the evidence against President Nixon. I followed their careers, as Thompson became an actor – well, he was always an actor – and a senator himself. Recently, I came across a story I had written in 1972, about possible legislation to limit strip mining – ripping coal from the surface of hilly Appalachia. The two proponents were Sen. Cooper from Kentucky (who was about to retire) and Sen, Baker from Tennessee, both Republicans, from coal states. I thought about the way current senators grovel in front of coal -- Joe Manchin of West Virginia (a nominal Democrat who sometimes seems like a nice guy) and Mitch McConnell of Kentucky (who does not, ever.) In the year of Trump and Carson and the nebbish Bush and the twerp from Florida I call El Joven, I remember a sunny day driving around Nashville with Howard Baker and Fred Thompson – and not feeling like I needed a shower afterward. What has happened? I heard the girls were heading south on I-75, known in the mountains as Hillbilly Highway because it takes people home on weekends and holidays.

Get off and take the Valley View Ferry, I urged. I used to do it whenever I could, from Louisville to Eastern Kentucky. Stop at the Kentucky Horse Park, I insisted. Don't forget the Boone Tavern at Berea. I sometimes forget how much I love that part of the world. * * * It's not Appalachian, per se, but treat yourself to the Gary Bartz version of "I've Known Rivers," adapted from the Langston Hughes poem, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9WCFQzznC4 I’ll be discussing my long relationship with Kentucky this Saturday in my town, Port Washington, Long Island – at the Dolphin Bookshop right after 3 PM.

Mostly I’ll be talking about how a few years of living in Kentucky gave me enough material to fill my head and my books and my articles forever. I doubt I’ll get to all the stories, so let me tell how this photo with Secretariat came to be taken: It started on May 6, 1989, when Sunday Silence won the Derby. At the media party late that night, a friend offered a tour of Stone Farm, where Sunday Silence’s sire Halo lived. Oh, and on the way back up Winchester Road we could stop at Claiborne Farm to see Secretariat. I am not a racing guy, never bet, have no clue who is running in the Derby on Saturday, but when I covered the Derby, I could learn the new cast of characters. Mostly, I loved the mystique of the Derby that makes Kentucky so different. I get misty when everybody stands and sings “My Old Kentucky Home.” I love the John Prine version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHcjwLoIFXE Plus, nobody passes up a chance to see Secretariat. First, we stopped at Stone Farm and visited Halo’s stall. I moved close to the wooden slats, only to feel the strong, insistent nudge of the groom, Handsome Sam Ransom, moving me back. “He bite your head off,” Handsome Sam said. The other horse people nodded. Mean SOB. I didn’t give Handsome Sam enough credit in my column that week: http://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/14/sports/sports-of-the-times-a-visit-to-the-father-of-champions.html We paid homage to Halo and his genes from a safe distance, then headed to Claiborne Farm. My guide, Fara Bushnell, who had some thoroughbred business with a couple of English buyers, handed me a couple of sugar cubes. Not supposed to feed the horses, she said, but…. We walked over to the fence, alongside a low hill of lush Kentucky bluegrass. I put a sugar cube on my palm. The hillside began to shake, better than an earthquake -- a 19-year-old, reddish of color, with a white patch on his nose. Big Red lumbered over. He knew the drill. A wet nose nuzzled my palm, taking his present.Then he stood still, allowing me to touch his swaybacked side. My friend snapped the photo. Big Red could go now. I never saw him run in person, but I have written about him dozens of times since, whenever some interloper tries to win the Triple Crown. I cannot tell you who the greatest baseball player or basketball player was, but I will tell you that nobody came close to Secretariat, the way he won the Derby, the Preakness, the Belmont. Five months after my visit, Secretariat was put down lovingly at Claiborne Farm. Enough was enough. They said the earth shook when he went down. The great Bill Nack wrote an homage to him that you really ought to read: http://www.si.com/longform/belmont/index.html Big Red is only one reason I revel in the legends of Kentucky – the miners, the politicians, the hard-shell county judges, the singers, the farmers, the complicated world of Louisville, the charming madam and collector of majolica in Bowling Green, Pauline Tabor. Kentucky was endlessly fascinating. (Don’t judge it by McConnell and Paul.) I’ll talk more at the Dolphin Bookshop, down near the scenic Town Dock in Port Washington, this Saturday. Hope to see you there. They played music from deep in the collective continental soul. Four Canadians and a drummer from Arkansas. First time I saw Levon Helm was backstage at the Garden during the Dylan tour in ’74. Somebody had placed a backboard outside The Band’s dressing room, and he was messing around with the ball, between shows. Wish I had said hello, but I was spying on Dylan’s sound check, so I kept moving. Now his family says he is dying of cancer. My favorite song from Levon is Ophelia because it is so….so…southern. Boards on the window/Mail by the door…. Reminds me of funky neighborhoods in the south, where people come and go. Although what could be more southern than Levon’s buzz-saw rasp on The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down? Only met him once. He played Loretta Lynn’s father, Ted Webb, in the movie Coal Miner’s Daughter. I had written the book for Loretta, and the movie people graciously invited me to the openings in Nashville and Louisville. I was afraid the movie-makers might commit a Beverly Hillbillies version about a part of the world I love. But as soon as I saw Levon as the slender, bashful miner, I knew the movie was going to be respectful. The second night, there was a party at the hotel, with Loretta and Sissy Spacek jamming together. Sissy could crack up Loretta by imitating her voice and her down-home bended-knee gestures. Levon was singing backup. It was the women’s show. During a break in the music, my wife sidled up to Levon and told him how good he was in the movie, and then she added, “You can sing, too.” He might have had a bit to drink, but not enough that he couldn’t detect the compliment. “Thank you, ma’am,” he said. “He was so cute,” she recalled on Tuesday, when we heard the awful news. We were in West Liberty once, visiting a gracious old lady in a double-wide. I recognized downtown on CNN, remembered a left turn into the countryside. When you live somewhere for a few years, it is always part of you, an alternate universe. My wife was driving along the Ohio one day, with our three children in the car. She had lived in Texas as a kid, and recognized a funnel cloud when she saw one. Get into the lowest ditch, the radio said, so she did, but the twister veered away. It’s coming to get us, she said after that. It’s coming right up Brownsboro Road. I covered a tornado in Green County that spring. A little boy, sleeping in his farmhouse, had been impaled in a splintered tree. By the time I got there, the sun was out, a beautiful spring day in Kentucky. Eighteen months after we moved back home, the same system that crushed Xenia, Ohio, blew straight up Brownsboro Road, demolishing the town houses on the corner, ripping the roof off our kids’ old school. This Friday night we held our breath for Henryville and West Liberty and all the rest from where we used to live. * * * Below: The view from the Courier-Journal Building. |

Categories

All

|