|

The backdrop looked familiar -- the Jamaica Ave., Elevated train -- The El.

It was the hub when I was a kid. In Sunday's NYT, there is a story about Brandon Blackwell, who broke into the British quiz shows, representing not Oxford, not Cambridge, but London's Imperial College. Great article by David Segal. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/business/uk-university-challenge-brandon-blackwell.html I hope you can access the article. *** Great stuff in the NYT in recent days. Wesley Morris wrote a literate and knowing article about the last show of "Curb Your Enthusiasm," 12 years of aggression and bruised feelings. I will admit, I never watched the show -- mainly because I had the feeling, "Wait, I know those people." I'm from New York, I know people in LA, I've had dealings with people in movies and journalism and just-plain-life. The only series I watched, obsessively, in the recent third of my life was "The Sopranos." I plotted my whole week around a TV set that carried it -- finding a motel on a reclaimed coal strip mine in Eastern Kentucky. I totally understand "Curb" fanatics. Wesley Morris, one of the best writers at the NYT, explains why Larry David annoyed and entertained people with his intrusive stands with friends and strangers. I hope you can access this masterpiece. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/05/magazine/larry-david-curb-your-enthusiasm.html *** Finally, has anybody noticed the reappearances of stars from the NYT sports section before it was disappeared in favor of stuff from a sports website? The stars have found places in the diaspora of former sports bylines, and have been encouraged to write wise and literate articles about sports, the kind readers used to expect: My Queens pal, Andrew Keh, has a piece in Sunday about soccer fans who congregate to a Brooklyn bar whenever their favorite team -- from Denmark -- is playing. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/07/nyregion/akademisk-boldklub-new-york-owners.html Billy Witz was assigned to write about the Caitlin Clark phenomenon at Iowa, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/02/us/march-madness-women-iowa-lsu.html And Talya Minsberg, a versatile editor and byline in the lamented Sports section, now writes for the Well section -- so naturally she explained the physical and mental training that brought Clark and Iowa to the NCAA finals. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/05/well/live/caitlin-clark-iowa-training.html As we used to say when I was a reporter on the National staff half a century ago, I detect a trend. May I quote Bruce Springsteen in his epic "Atlantic City:" Everything dies, baby, that's a fact But maybe everything that dies some day comes back In the midnight hour on a murky Saturday night in late October of 1986, Shea Stadium was going mad.

A squiggly grounder by Mookie Wilson had somehow kept the Red Sox from winning the World Series that night – and fans were screaming, and nearly a dozen New York Times writers were pounding away at their laptops, shouting into phones, bustling noisily to update their early stories for the last print deadline of the evening. Enlightened cacophony. The sports editor, Joseph J. Vecchione, sitting behind us in the pressbox, was coordinating with the staff in the office, making dozens of decisions, on the spot. Then it was over. We had gotten it done, on deadline. A young Times news reporter, doing spot duty to cover fan madness, police activity, etc., watched the sportswriters (so often maligned as “the toy department”) do their jobs. When things quieted down, the young reporter said casually to the sports editor, “Wow, that was impressive,” or words to that effect. And Joe Vecchione said drily: “We do it every day.” If Joe had added, “Kid,” he would have sounded just like Clint Eastwood in “The Unforgiven.” That professional pride epitomized Joe Vecchione, my friend and advisor in my early days of writing the sports column. Joe passed Friday evening at 85, after years of suffering from Lewy body disease, cared for by his wife, Elizabeth, a wise and devoted nurse. They are parents of Elissa Vecchione Scott and Andrea Vecchione, with three grandchildren: Joe’s aura of family man was clear to people around him. He was a boss with values. I got to know him as a terse, decisive voice on the phone, in the 70’s, when he was an editor in the photo department, and I was a news reporter. Sometimes I was at breaking news and I had to coordinate with the photo editors. Joe was authoritative and efficient. Then he was plucked by Abe Rosenthal and Arthur Gelb to help form the new SportsMonday section, and he was there in 1980 when sports editor LeAnne Schreiber recruited me to be a reporter, filling in for Red Smith or Dave Anderson here and there. When LeAnne moved on, Joe became sports editor, and when Smith died in 1982, it was Abe Rosenthal’s decision to hire a new columnist, and it turned out to be me. Here is where the kindness and shrewdness of Joe Vecchione took over. I had been conditioned by 10 years as a Times news reporter, to keep any trace of myself out of the copy. Give sources. Quote authorities. No opinions. That was the old, gray NYT – and I was one of the foot soldiers, thoroughly indoctrinated. As a columnist, I knew the subject matter, and could write and report, but I was trying too hard to find a voice, hinting at my opinions. I was being too cute. Joe had some advice (and I paraphrase:) “Be yourself. Tell us what you think. People want to know how you feel, what you know, what is right and wrong. Don’t hold back. This is the way things are going these days. You have freedom.” He removed a decade of thoroughly valid reportorial rules, freeing me up to be a columnist. Joe also had an instinct for hiring and enabling good people, hiring columnists Ira Berkow and Bill Rhoden, relying on deputy editors like Bill Brink and Lawrie Mifflin, and he backed up his columnists. I benefited from this in 1990, when I was writing columns from the World Cup of soccer, held in Italy. The young American team, in its first appearance in 40 years, managed a taut 1-0 loss to the Italian team – a huge accomplishment. But I pointed out that Italy did not have great strikers – that is, players gaited to score goals from up close – and I wrote this was because their great national league imported scorers from Germany and Argentina and Brazil. I wrote: “The home-grown players do not develop the knack of scoring. Mussolini once lamented that his was a nation of waiters. It is not stretching the truth to say that Italy is currently a nation of midfielders.” The next day, the sports department got a call from an Italian-American reader who felt using the remark attributed to Mussolini was prejudicial. (Fact is, I love Italy and root for the Azzurri, except when they play the U.S.) The person in the office, taking the call, told the reader that the sports editor was okay with my comment. And who is the sports editor? “Joseph J. Vecchione.” That pretty much ended the conversation. Joe could be tough, and he had to make a lot of decisions. I once was whining in the office about something or other, and Lawrie Mifflin, the deputy sports editor and loyal friend of Joe’s and mine, told me, in effect, “You have no idea how much he has to handle every day” – including complaints from leagues, teams, player unions, sponsors, agents, public officials, fans, to say nothing of staff members. In Joe’s regime, we let it fly, and Joe fielded the complaints, kept most of it from our ears. Joe was sports editor for a decade, then moved back into the mainstream of the paper. He retired at 65 and the editors promptly brought him back to help the transition to the new building a few blocks away. Over the years, I was impressed by the masthead names, the serious people (some of whom condescended to sports personnel), who were his social friends. They trusted him – for core values, like honesty, like thoughtfulness, like culture. That is no small statement about a Times official, my friend, who helped move the sports department into the future. (Any insights/anecdotes about Joe? Please add them in Comments, below.) Yes, yes, I know. I grew up (and suffered) when the Brooklyn Dodgers lived in the same town as the New York Giants and Yankees. (Bobby Thomson! Yogi Berra!) But that’s long gone.

I know all about the long Yankee-Red Sox rivalry, and the great football and basketball and hockey rivalries. I covered Ohio State-Michigan football back in the day, and the glorious Lakers-Celtics finals in the mid-80s and Islanders-Rangers (The organ and the Potvin Chant in the Garden!) But nothing is like Mexico-USA in soccer, for sheer nastiness, in a sport based on precious goals – and fueled by long-held stereotypes and resentments. History lesson: you cannot be casual against the Mexicans. Planted in their memories is a computer chip from 1847 when Gen. Winfield Scott marched his troops from Vera Cruz to Mexico City. (“From the Halls of Montezuma….”) The two squads had another episode of their rivalry Sunday night in Denver, in the finals of a regional tournament called the Nations Cup. There were homophobic chants, apparently now a staple of Mexican “fans,” plus bottles and other stuff flying out of the stands, one hard object conking Gio Reyna, the 18-year-old wonderboy who had scored the first restorative goal for the U.S. ( Apparently, he is okay.) All that stuff is deplorable, but the rivalry, the history, this great sport itself, is compelling. It held me for three hours in front of the tube Sunday night, watching the US rally twice for a 3-2 victory with repeated and late heroics. The Mexican players are always fired up; sometimes the U.S. players need a reminder. At 60 seconds, an American defender made a super-cool pass to his right to clear the ball from goal mouth, but the Mexicans were in predatory gear and poached the pass for a goal, making the evening seem disastrous. Hard lesson: You cannot be casual against Mexico, which has world-level talent, polished in some of the best leagues in Europe. The U.S. is just catching up. Never forget. Three American former players in the pre-game TV booth remembered that lesson. In 2009, in a qualifying game for the World Cup, in that ominous, rumbling torture chamber known as Estadio Azteca, Charlie Davies scored against Mexico in only the 9th minute, and tore off toward the stands to exult, wherever American fans happened to be. “See you later!” recalled Clint Dempsey and Oguchi Onyewu, his boothmates, two older players who also were on that field in 2009. They watched the talented, exuberant and innocent Davies strut into a barrage of debris from Mexican fans and quickly seek the safety of midfield. (Oh, yes, Mexico rallied for a 2-1 victory in front of the home crowd that night. Tough place. I remember one U.S. match in Azteca, 2001, when the U.S. bus parked in a so-called secure area, only to be harassed by a lone heckler – a borracho, a drunk, a dwarf on a carpeted skateboard, given the run of the lot, rattling off Spanish and English maledictions at the visitors: Bienvenido a Azteca. Every moment on the field is a battle. Personal. On Sunday, after a Mexican goal was disallowed because of a minimal offsides violation, Reyna, only 18, scored the equalizer in the 27th minute. In the stands, his parents, Claudio Reyna and Danielle Egan Reyna, both former American players, celebrated. I immediately flashed back to the best game I ever saw cool, selfless Claudio play, in the round of 16 in the 2002 World Cup in Jeonju, South Korea. He distributed the ball and defended and overtly set the tone for a 2-0 victory – also the best game I have ever seen the U.S. play, knocking out their rivals and moving into the quarters where they would lose, controversially, to Germany. (That score was familiar, from a World Cup qualifier in a storm with wind and rain and evil greenish clouds, in Columbus, Ohio, in 2001, soon prompting a chant: “dos a cero!”) There were three other dos-a-cero American victories in that decade. Sunday night’s game was not 2-0. Mexico scored and Gio Reyna tied it. The American keeper, Zack Steffen, went out with a knee injury in the 69th minute, and his replacement, Ethan Horvath, hastily warmed up, getting more action than Steffen had, and responding marvelously. Late in the overtime, two Mexicans put the squeeze on Christian Pulisic, the aging wonderboy, now all of 22, who went down, and drew the penalty kick. Pulisic coolly placed the ball in the upper-right corner (“where the spiders play,” said one of the American ex-players in the booth). Some Mexican fans promptly unleashed a homophobic chant – against nobody in particular – and the regional officials threatened to halt the match and replay it Monday behind closed doors. (NB: most of the Mexico fans, many residing in the U.S., are sportsmanlike.) “Bonkers,” was the perfect description of the mood swings, by my friend Steven Goff, longtime soccer correspondent for the Washington Post. In the closing moments, Horvath had to defend a penalty kick by the venerable Mexican captain, Andres Guardado, just off the bench, and he dove to his right to punch away the shot for the victory. Later, as quoted by my man Goff, Horvath said he had been well prepared for tendencies during the week by his goalkeeper coach, using films from other Mexican matches. (My long-time colleague, Mike Woitalla of Soccer America, rated Horvath a 9/10 for his spontaneous heroics. Reyna and Pulisic were rated at 8/10.) The U.S. celebrated – mostly toward the center of the field. Always a good idea. But the giddiness will fade quickly: Mexico still holds a series lead of 36 victories, 16 draws and 20 losses – and keeps producing talent. (I was struck, particularly, by the skill and gall of Diego Lainez, all 128 pounds of him, three days short of 21, who plays for Real Betis in La Liga of Spain. Mexico could afford to save him for the 78th minute; he did not score until the 79th minute, and spent his spare time lobbying the field official.) The rivals are probably fated to meet again in the qualifying stages for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. Whenever they meet, there will be epic plays and mistakes and oaths and missiles from the stands, as well as moments of world-level soccer skills. For me, whenever the two squads meet, in a “friendly” or a World Cup match, it’s the best rivalry in North America. *** Try to access my NYT article from 2001, from the testing grounds of Azteca: https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/01/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-yanks-reach-for-new-heights-at-an-old-altitude.html See if you can access the wrapup via that great asset, Soccer America: https://www.socceramerica.com/ Ditto, the Goff article in the WaPo: https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/06/07/usmnt-wins-mexico-nations-league/ Wikipedia has all the details of the Mexico-USA rivalry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexico%E2%80%93United_States_soccer_rivalry  Not too long ago, Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow were gracing the sports pages of The New York Times with their wise columns. Now they are both issuing books with their very personal views of the world. Harvey’s book is “Our Last Season: A Writer, a Fan, a Friendship,” about the bond between him and Michelle Musler, who for decades was a fixture in the stands just behind the Knicks bench in Madison Square Garden. Ira’s book is “How Life Imitates Sports: A Sportswriter Recounts, Relives and Reckons With 50 Years on the Sports Beat,” which just about tells it all. (In alphabetical order) Araton praises the wise businesswoman who was always there – for the Knicks and for him. He describes himself as the child of a project in Staten Island, who earns his entry into sports journalism while battling his own insecurities. As he works his way from the Staten Island Advance to the Post to the Daily News, his talent and earnestness impress not only editors and readers but also a fan literally looking over his shoulder in the Garden. Musler saw all – could read the body language, maybe even read lips, of the Knicks and the opponents and the refs. She had put her people skills to great advantage in the corporate world, undoubtedly by being wiser than the average (male) executive. The Knicks were her outlet, she freely told friends, her social life. Everybody knew her – the players, nearby fans, reporters, ushers, even the team PR man, who left a packet of media stats and releases for her before every game. How cool was that? Musler more or less adopted Harvey, counseled him, shaped him up, told him to aim big. She became friendly with Harvey’s wife, Beth Albert, and sometimes met Harvey after a game to debrief him on what she had seen from her perch. When he fretted whether he was worthy of the Times job being offered, she figuratively slammed him up against a steel locker and gave him what a high-school coach I knew called “a posture exercise.” And when his career took a sour detour, she shaped him up, to the point that in retirement he remains an extremely valuable contributor to the Times sports section. Harvey is still what somebody once called him: “The Rebbe of Roundball.” In return, Harvey came to know Michelle Musler – her strange childhood, her husband leaving her with five children, her career, her need to make money, her love of the Knicks. Her decades of working with male executives prepared her for a searing analysis of James Dolan, the miserable owner of the Knicks. As Michelle’s health deteriorated, Harvey would sometimes drive from New Jersey to Connecticut to the Garden to get her to a game. And when Michelle Musler passed in 2018, Harvey wrote a beautiful obit for the Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/obituaries/michelle-musler-courtside-perennial-in-the-garden-dies-at-81.html  Ira Berkow’s book is also personal – about a talented, ambitious kid from Chicago who made his way to New York and became a fixture in the Times and also in books, not all about sports. Ira has touched on most stars of the past half century – Muhammad Ali! Michael Jordan! He sized up O.J. Simpson, before and after! He had lunch with Katarina Witt! He shot baskets with Martina Navratilova! He also shot baskets with a retired Oscar Robertson! He schmoozed with Abel Kiviat, then America’s oldest living medalist! And he scrutinized a brash real-estate hustler named Donald Trump! One of my favorite segments is about Jackie Robinson – who broke baseball’s disgraceful color barrier in 1947. Ira recalls being 15, a high-school athlete himself, watching the Dodgers take on the Yankees in the 1955 World Series. In 2018, with JR42 long gone, Ira was being interviewed on TV about Robinson and came up with a description of how Jackie Robinson had faked the Yankees’ Elston Howard -- a catcher playing left field -- into throwing the ball to second base while Robinson steamed into third. Later, he remembered interviewing Robinson in 1968 about his thought processes in testing Howard, who was out of position because Yogi Berra was the catcher. Robinson seemed to deflect Ira’s analysis, but the audacious move remained in Ira’s fertile brain. A few years ago, Ira looked it up in the official play-by-play for the 1955 Series: it confirmed that Robinson, by whatever logic, had victimized Howard into throwing behind Robinson. This section confirms the instinctive genius of Jackie Robinson and also the enlightened journalistic observation powers of Ira Berkow. * * * Most of sports have been thrown off balance by the pandemic, but these very different books by Harvey Araton and Ira Berkow remind us how great sportswriters have enriched us by writing about the world, on and off the court. NB: Please save your best stuff about resumption of BB/Soccer, seasons, etc.. I am planning a piece on this by midweek when the plot thickens some more. Best, GV * * * Last week I wrote about missing the Kentucky Derby – the place, the season, the event itself. Some readers mentioned other grand sports sites and events – Jim Nabors singing at the Indy 500, walking into Yankee Stadium (or almost any other ball park) and seeing the green grass, a day trip to Saratoga during “the season.” I wracked my brains about sports places I have visited: --Ebbets Field in 1944, when I was 5 and my dad took me to an off-season bond drive event. --My first assignment to Notre Dame football in 1964, remembering a nice man up the block when I was a kid, who took me to see a few live Notre Dame games in a movie house in Flushing, and told me proudly about having been on a great Notre Dame team and never, ever, getting into a game. --Azteca Stadium in Mexico City in 1986, feeling the place physically rock when El Tri was on the move – the appeal of any home team during the World Cup, but particularly for our neighbors to the south. That was just three off the top of my head. Last night I remembered going to the Montreal Forum in 1984 and getting a tour from Camil DesRoches, the grand old publicist of Les Habs. Camil was old school – suave, bilingual, mustached, loved the cultures of Canada plus the U.S. He implanted the lore of Les Habs in my brain, so I wrote about it. I kept up with Camil for many years after. He would send me cassettes, particularly of Montreal’s chanteuse, Danielle Oddera, and her duets and interpretations of Jacques Brel. Nowadays, the Forum is a cineplex; my friend Camil DesRoches passed at 88 in 2003; I still treasure my visit to this home to a great team, a great culture. Please write about a sports shrine in your life: * * * My column from 1984: SPORTS OF THE TIMES; FIRST VISIT TO THE FORUM By George Vecsey

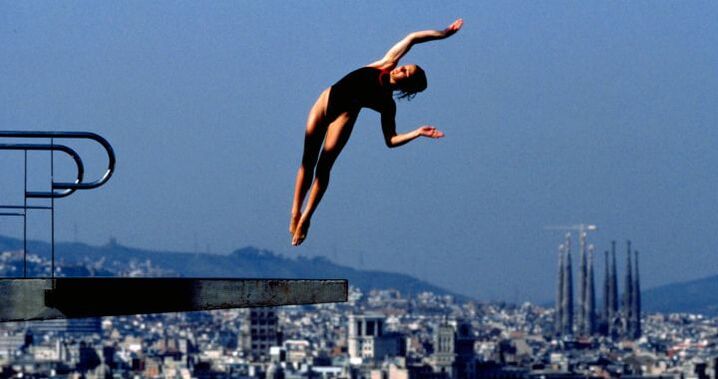

He pointed to a color photograph on his office wall, a picture of the Montreal Canadiens who won their fifth straight Stanley Cup 24 springs ago. His total impartiality was tempered not in the slightest by his being employed by the Canadiens for the past 46 years. Camil DesRoches spent yesterday morning escorting a greenhorn on his first visit to the Forum, a pilgrimmage somewhat akin to the first visit to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, or St. Peter's in Rome or Westminster Abbey in London: the feeling of closeness to the soul of a people. ''I always say that hockey is like a religion here in Quebec,'' Camil DesRoches was saying. ''We are perhaps 90 percent Catholic, but we are all hockey fans.'' Camil DesRoches is a classic Gallic gentleman, nearly 70 years old, with a thin mustache and a large heart. He loves his wife, he loves Broadway musicals (he saw ''Oklahoma'' 26 times), he loves wine (''We have never had a bottle of milk in my house, and I still have all my teeth''). But just as strongly, he loves the Canadiens, and he loves the Forum, for which he is now the publicity director. He was conducting the tour on a day of both sadness and anticipation. Yesterday morning, there was a funeral for Claude Provost, a member of the five-time Stanley Cup champions, who died on a tennis court in Florida last week. Later in the evening, the current Canadiens would work on stopping the Islanders from winning a fifth straight Stanley Cup. The Islanders were taking a brief workout as Camil DesRoches led the visitor into the stands. Outside, on a perfect spring morning, the Forum seemed an ordinary brick building, surrounded by traditional Montreal tenements with their dark fire escapes. But inside, the Forum seemed a holy place, where one lowered his voice. On the morning a Canadien was being buried, it was not hard to remember that in this building in 1937 the body of the great Howie Morenz was put on public display after his death from complications following a broken leg (suffered, as the history books always say, when he crashed into the boards on the St. Catherine Street side of the Forum). The Forum was filled with 15,000 people, yet it was as silent as a cathedral. Yesterday the Forum's lower red seats glistened, as if painted five minutes earlier, and so did the middle white and upper blue sections, forming a classic tricolor. The stands of the Forum are oval-shaped, following the shape of the rink itself, just as the best bull rings and soccer stadiums of Europe are tailored for one sport, rather than multi-purpose arenas not quite right for any sport. ''There used to be eight columns,'' Camil DesRoches was saying. ''So in 1968, we rebuilt the Forum completely in five and a half months months, leaving only the seats. Look how narrow they are. But nobody complains, because we get more people in that way, 16,400 seats in all.'' From the rafters hang 22 banners, signifying the club's Stanley Cups, 20 of them won since the Forum opened in 1924. ''The best game I ever saw here?'' he said. ''Maybe in 1936, when the Maroons beat Detroit in six overtimes when Mud Bruneteau scored. I got home at 2:25 AM. Or maybe it was Dec. 14, 1965, when our so-called amateur club beat the Russians using Jacques Plante, who had just left the Rangers a few months earlier. ''Or maybe it was March 23, 1944, when Maurice Richard scored all five goals to beat Toronto, 5-1, and they named him all the top three stars of the game. Or what about the game in 1979, when Boston got a penalty in the last minute and Lafleur and Lambert scored to win it?'' The pucks from the Islanders' target practice started slamming into the shining red seats, so Camil DesRoches continued the tour. He pointed out Le Salon des Anciens - the Old Timers' Room - where former Canadiens are welcome. The Canadiens are noted for their propriety, including a private room for the wives of the players. Only recently have patrons been allowed to carry beer to their seats, an experiment that would end at the first abuse. In the lobby, two escalators form the pattern of crossed hockey sticks, a sight Ken Dryden, the retired goalie, always found compelling. Nearby, is the Pantheon of Montreal hockey, the plaques of 30 players and coaches from Quebec who had their best years wearing the bleu, blanc, rouge. Near the entrance is Le Club de Bronze, 11 bronze busts of journalists and broadcasters considered to be friends of Montreal hockey. The 12th bust is of Camil DesRoches. ''I feel funny every time I see that,'' he said with a shrug. The next stop was the Canadiens' dressing room. On one wall are plaques containing the names of every player since 1917. Above the lockers is a line from Dr. John McCrea's poem, ''In Flanders Fields.'' In English it says: ''To You, From Fallen Hands We Throw the Torch, Be Yours to Hold It High.'' On the other side of the room, Camil DesRoches has translated it into French: '' Nos Bras Meurtris Vous Tendent Le Flambeau, A Vous Toujours de le Porter Bien Haut.'' Camil DesRoches said: ''I have been told I did a good job of translating but also making it rhyme in French.'' Over a glass of vin rouge, Camil DesRoches talked of being the youngest of 19 children, of being taken to the cellar when he was 6 years old and being shown the barrel of beer and the bottles of wine. ''My father said: 'You are almost grown up now. You can drink what you want - but never get drunk.' I got drunk once, when I was 17, and my father made me stand almost naked in front of my family, in that condition. I never got drunk again in my life.'' Sipping his wine, he compared three of the great Canadiens of his 46 years: ''Maurice Richard was the Michelangelo of hockey - such dedication, he would work on his back painting the Sistine Chapel, never give up. Jean Beliveau, complete finesse, what style, he was the Da Vinci of hockey. And Guy Lafleur is like Raphael, whose career was not long, but he was an artist and he had a great time.'' When lunch was over, Camil DesRoches concluded: ''I hope you enjoyed the visit to the Forum. Also, I hope you see what it means to our French environment here in Quebec, just like the language, part of our life.'' ###  The classic view from Montjuich, the Olympic site in Barcelona, facing the classic (and unfinished) Sagrada Familia. John Jeansonne, my Newsday pal, refers to Montjuich as a sports shrine in his comment below. GV The classic view from Montjuich, the Olympic site in Barcelona, facing the classic (and unfinished) Sagrada Familia. John Jeansonne, my Newsday pal, refers to Montjuich as a sports shrine in his comment below. GV  Orson Welles. Seventh Game. Same night. Orson Welles. Seventh Game. Same night. Omigosh, you never know what will pop up. I picked up “the paper” in the driveway on Monday and there in the sports pages was a column I wrote 33 years ago, and it seems like yesterday. Actually, it did involve two yesterdays – a seventh game of a Stanley Cup series that began Saturday night outside Washington, finished Sunday morning on Long Island (I was columnizing from home) and appeared in the Monday paper. In those days, there was no Web, no 24-hour urgency to the newspaper business. I watched the Islanders (descendants of the mythic champs I had loved covering from 1980-83) battle the upstart Capitals for the right to move on to the next round. Sports columnists were caught up in the interminable pedaling on the hamster wheel, the typing, the travel, the creating - - a mission, an honor. Only six months before, also on a Saturday night, Mookie Wilson and Bill Buckner had gotten caught up in another epic game. In the long madness of that night, I declared that the Red Sox’ misery was somehow linked to their disposal of Babe Ruth nearly half a century earlier. One gets very wise very late at night. (And speaking of momentous marathons in the middle of the night, one of my favorite books about sports, and suffering, is “Bottom of the 33rd,” about baseball’s longest game between Pawtucket and Rochester, by Dan Barry, now one of my favorite bylines at the NYT. By the quirks of the calendar, that April 19 was both Holy Saturday for Christians and Passover for Jews, spiritual overtones galore.) The Islanders-Capitals marathon also began on Holy Saturday and led into Easter Sunday while the lads kept playing, and playing, and playing. I was living the life of the sports columnist, circa 1987 – when you knelt before the editor-in-chief and he tapped you on the shoulder with a mythical sword and dubbed you a knight of the keyboard, giving a modest raise for the honor of working your fingertips and frazzled brain around the clock, around the calendar-- three or four columns and week, often on deadline, deputized to explain sports to Times readers (and editors.) I took my mission seriously and went out to slay dragons around the clock, around the week, around the cycle of sports as we knew it then. Fact was, I loved it, the freedom to think, and type, and see it in the paper, regularly. (How trivial it all seems now, when most of the “news” of sports is about whether to resume competition, while in the Real World people are merely hoping they and their loved ones can continue breathing and eating. It is just possible that the longing for sports only leads to more Foxed-up yahoos picketing state governments to get people “back to work,” no matter what those scientists say about the killer virus. Personally, I don’t miss sports at the moment, well, except for the Mets.) As my column from April 1987, materialized in the NYT, I was proud to read the way a columnist could converse regularly and familiarly with readers. After the Islanders outlasted the Caps, I seem to have slept for a few hours, and gotten up early on Sunday and written about our Saturday evening – walking the dog often, my wife prepping Easter dinner (we had two friends coming for dinner), our youngest-the-busboy coming home from Louie’s smelling like fried shrimps, and how I switched channels so often that I also watched chunks of my all-time favorite movie, “The Third Man.” But I wrote the column – keeping the faith with the holy mission of the sports columnist. Thirty-three years later, how much fun it was – and still is. * * * Here is the 1987 column: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/04/20/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-late-late-show.html?searchResultPosition=1 Here’s a review of Dan Barry’s lovely book about the longest baseball game: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/25/books/bottom-of-the-33rd-by-dan-barry-review.html?searchResultPosition=1 |

Categories

All

|