|

Here’s a Santa’s workshop for you – the local bicycle shop, packed with gleaming machines with that nice-new smell.

But here’s the problem: I dropped into Port Washington Bicycles at 18 Haven Ave. in Port Washington, L.I., the other day, to say hello to the staff that keeps me rolling all year long. Things were way too quiet for December. People are not making a big rush on bicycles for holiday presents for children, the staff told me. Apparently, kids hunker in their homes, flicking their smartphones, playing games and gaping at who-knows-what. They are using their thumbs when they should be using their knees. “It used to be that when kids were punished, they were made to stay indoors,” said John Pappas, one of the bosses. “Now if they are being punished, they are sent outside.” It is a true social phenomenon. As American children grow heavier, they do less. Helicopter parents drive them to play dates. In our neighborhood park, we have modern play equipment with all the apparatus clustered, so parents can hover, holding cellphones and Starbucks cups. Gone are the days when kids could swing or climb in a corner of the park, daydreaming, or take a walk or ride a bike, looking for their friends in the neighborhood. At least, that is how it looks to me, as well as Ralph Intintoli, the owner of Port Bicycles, and his two colleagues, Pappas and Mike Black. Over the years they have sold me a Schwinn and more recently a Trek Hybrid, as well as a treadmill and an exercise bike. They also sell car racks and are terrific at service. Pappas also gives paid lessons when it’s time for children to stop using training wheels and take off on a two-wheeler. However, at holiday time, when the newest electronic gadget is the present kids absolutely must have, parents don’t buy the traditional new bike to put under the tree. Actually, grandparents buy bicycles for kids more than parents do, Intintoli said. When I was there, a guy my age was buying a beautiful Trek to bring to a grand-daughter on a Christmas visit. I hope the girl appreciates the gift, and takes off down the block to play with a friend. I know my friend John McDermott is a great soccer photographer because I have seen his work for over 30 years.

I also know of his fondness for Italy because of his chats, in Italian, with some of the great names in Serie A. Recently John and Claudia moved from the western outpost of Italy -- North Beach, San Francisco, that is -- to the northeast corner of Italy where he can hear Italian and she can hear German spoken, sometimes at the same time. John did not need to go to the Giro d'Italia this month. It came to him. He found his spots here and there -- kind of like knowing where his pal Roberto Baggio liked to poach -- and he clicked away. This is just a sample. Other photos can be found on his sites: www.mcdfoto.com www.instagram.com/johnmcdermottphoto  Kerry in Yellow, in Perhaps Treasonous Activity Kerry in Yellow, in Perhaps Treasonous Activity This time Trump has gone too far. He has made fun of Carly Fiorina’s face and sneered at Mexicans, aiming at the angry white male. Now he has taken on John Kerry for committing the federal crime of riding a bicycle as a septuagenarian. “They have no respect for our president, they have no respect for John Kerry, who falls off bicycles at 73 in the middle of a negotiation that’s very important,” Trump said in August. He paraphrased it Monday night, again criticizing the Iran nuclear treaty. Of course, Trump exaggerated Kerry’s age. Said he was 73. In fact, Kerry is 71. Take it from a far lesser cyclist who tumbled on sand, every year counts while pedaling uphill More to the point, Trump has once again pandered to the know-nothing set, this time in Dallas, making fun of Kerry’s love of cycling – the high-tech bike, the full outfit, the challenge of a Tour--level mountain in Switzerland. Trump perhaps knows this is something thousands of men and women do daily in Europe and elsewhere, imitating the great cyclists on the hardest hills they can find. But he panders to the base. Classic Donald. He said the Secretary of State was riding in a race. In fact, Kerry was taking on a Tour incline in May, but with his own State Department motorcade, which rushed to his help when he struck a curb and toppled, fracturing his leg. Yes, the injury was serious enough to warrant surgery and care in New York. Trump senses it will work as part of his shtick about Kerry. In his rally in Dallas, Trump once again imitated Kerry’s return to work. Simulating a man walking with crutches, he said, “The people from Iran say, ‘What a schmuck.’” This is a common theme with Trump – the queasiness with anything less than a perfect 10. Trump seems pathologically uncomfortable with human frailty. What must he think of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who ran a country in terrible times, limited by polio? The fear of frailty, this discomfort with complexity, accompanies him on national television, babbling about himself -- the Reality Show Host as Candidate, for goodness’ sakes. Undoubtedly, Kerry was inconvenienced by his accident, but there are such things as telephones and cables and the Internet. We have seen footage of Kerry with his Russian and Iranian counterparts. The body language tells me they do not consider him a schmuck, with or without crutches. Kerry also speaks French fluently, undoubtedly a drawback to Trump’s base, maybe even to Trump himself. French was a skill Mitt Romney tried to hide during his stiff race in 2012. Why would the United States want a worldly President or Secretary, anyway, when the current rage seems to be a carnival clown, who cannot even get ages right. What a strange sport, cycling.

More than any sport, it contains multiple stories and multiple champions, wheel to wheel on narrow mountain roads. The Tour ended Sunday where it always ends, in Paris, with the Eiffel Tower in the background. When the survivors struggled up the Alpe d’Huez on Saturday, either Phil Liggett or Paul Sherwen, both English, noted on NBCSN that from the peak of that mountaintop the riders could see the Eiffel Tower. Whichever one it was, he was being poetic, but what a symbol for this singular event. I remember the penultimate race in 2004, a time trial out east in Besancon, that made Lance Armstrong champion for the sixth straight year. As soon as work was done, I jumped into the car with James Startt and Sam Abt, two Americans in Paris. James started his engine and gunned onto the Autoroute. I close my eyes for a few minutes and woke up and saw a strange phenomenon looming out the back window. It was the Eiffel Tower, all lit up on a summer evening. James had found a time warp. We were in Paris. The same thing happened Sunday in rainy France, when the peloton skidded its way into Paris on the ritual final day. Every finisher was a champion of the human will. That’s why people stand in the rain or sun and cheer. Saturday’s true finish up the Alpe d’Huez had three champions, all properly celebrated by Liggett and Sherwen. . There was a Frenchman, Thibaud Pinot, barreling ahead on the final climb, to win the stage, a victory for the host country, living on the memory of past glories. (Like England in soccer.) Then there was a Colombian, Nairo Quintana, showing panache, the favored character trait of the Tour, by trying in vain to win the Tour with a blast up the Alpe. And there was the actual winner, Chris Froome of Great Britain, who gained from a great support system and his own dogged riding, to win another Tour. It is a strange sport. My friend Alan Rubin, soccer keeper and mentor, added a comment on this site recently, wishing he knew more about the sport. I always felt the same way -- and I was covering it, or at least writing columns, often about the apothecary wing of cycling. The best I could tell Alan is that the Tour is a mix of the Daytona 500, the New York Marathon, the roller derby, and the old single-wing formation in American football, when everybody pulled to lead the ball-carrier. My advice would be to read the collected works of Daniel Coyle, David Walsh, John Wilcockson, Juliet Macur, Sam Abt and James Startt. You’ve got almost 49 weeks. (Sam Toperoff lives in the Alps with his family. He played basketball at Hofstra and later taught there and has had an admirable career writing books and documentaries before retiring in France. The Tour de France has been in their region in recent days; I suggested he send his impressions.

(At first, Sam was going to write from the largest town, Gap, but then he wrote why that was not possible: (“Local shepherds will be staging a manifestation – protest -- because the government is protecting wolves, which they claim are attacking their flocks. Italy, just across the mountains, doesn't have a wolf problem because the shepherds sleep with their flocks; French shepherds do not. Still, the local shepherds plan to disrupt the Tour by loosing 3,000 sheep when the cyclists approach Gap. Seriously. I'm not making this up; this is France, and I love it.” (Instead, Sam waited until Thursday, and he wrote these words and his daughter Olivia took some photos.) By Sam Toperoff Good evening Mr. and Mrs. North America and all the ships at sea, let's go to press. (It's an opening that takes me back to my childhood and so does riding a bike around Laurelton, Queens, when I was about nine or ten.) I always thought bikes were for kids. Not in Europe they ain't! I've never been as taken with the Tour de France, the best bike-riding ever, since I watched the great Bernard Hinault bike past me to victory forty years ago on an uphill climb I could barely manage while walking. I had found myself in the French Alps par hazard and since there were no basketballs around and no one to hit fungoes to, I had to start biking. Frankly, it was the most demanding physical activity I'd ever engaged in. I biked these hills in summer until I was seventy. I actually put the bike away on my birthday after I came up two hairpin turns from a road below my house and barely made it. The other day, to win the 18th stage of this year's Tour, Romain Bardet went up scores of hairpins and scaled the Alps themselves during a 170-km. race while being chased by 170 other world class riders. These are remarkable athletes indeed because of the physical and mental demands they face daily over three-week period. All in all, the race is over 2,000 miles. Bardet is a young Frenchman, and a Frenchy winning even a stage has become a rarity these days; no one from Gaul has won the Tour since the above-mentioned Hinault, who did it thirty years ago! And so tonight, French television is nothing but Bardet, Bardet, Bardet. Of course, it's hard to watch the Tour without wondering how these men can do what they do, especially when it comes to their need to recover overnight after such enormous effort. Even though all of Lance Armstrong's victories have been vacated because of his now-admitted use of illegal stimulants, it is hard to watch such remarkable performances and not remain somewhat cynical. The Director of the Sky Team, for whom Christopher Froome rides, the Englishman Sir David Brailsford, is on television almost daily assuring viewers (his French is perfect) that his team is clean. "I don't blame people for being cynical," he said the other day, "but other than the unlimited testing of my team and giving the public my word, what can I do?" The shadow of Lance Armstrong still shades the Tour. I despise him for what he did. Worse, he put doubt in my appreciation of what I am witnessing; cynicism's worst effect is that it robs one of pleasure. And poor Chris Froome -- a truly great rider -- and young Romain Bardet -- and my particular favorite Alberto Contador -- they all become objects of suspicion. Nevertheless, I'll be in front of my set for tomorrow's stage.” Merci, Sam. It was my first day around the Tour de France, a rainy morning, July 14, 1982.

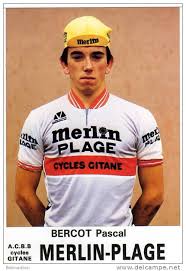

There was a time trial that holiday, around Valence d’Agen in the south, but it was too early to go out in the rain. I was with Roby Oubron, former cyclo-cross champion and then a mentor to Jonathan Boyer, the first American to ride in the Tour. Roby was a true son of France, a resister during the war who loved America. He met me for breakfast in the hotel and brought along a friend, but I did not catch his name. I tried to follow the shop talk in French, and they slowed it down enough for me to be included. We dawdled over breakfast, more than the basic croissant and café au lait. Then I asked the waiter for the check. “Ah, non!” Roby blurted. His friend, a polite older man in nondescript foul-weather gear, was also asking for the check, but I had gotten there first. Trying to overcome the language gap, Roby explained that his friend was wealthy, loved cycling, and always paid, always. I politely told the man that the New York Times would insist, journalistic ethics and all. The man seemed bemused by the concept of journalists grabbing the check, but he nodded his head gravely and thanked me. Later, in the car, racing around behind Boyer on the time trial, Roby explained to me, as best we could work out, that his friend was Guy Merlin, the founder and proprietor of Merlin leisure homes and camps all over France. Guy Merlin sponsored cycling teams, and his $20,000 condominium in the south of France was the largest prize for cyclists on that 1982 Tour, I found out later. We barreled around southwest France the next few days -- Rob Ingraham, Boyer’s agent, called Roby “Mario Andretti," for his heavy foot – and my short visit ended up in the Pyrenees, with the goats. Roby knew everybody. He would drive alongside Bernard Hinault on some narrow mountain pass and ask why he was making a breakaway. It was like sitting in a baseball dugout during a game with a wise elder like Ted Williams or Roy Campanella. I adopted Roby as my alternate father-figure and think of him every Quatorze. As long as Roby lived, he told the story of how I grabbed the check from Guy Merlin. * * * Bonus: a short video of Roby winning a cyclo-cross stage, July 12, 1945, apres la paix. http://boutique.ina.fr/video/AFE86003353/robert-oubron-remporte-le-cyclo-cross-delavigne.fr.html I was watching the Tour de France on Tuesday morning as it swept through the city of Charleroi, in Belgium.

My mind went back to a nasty morning in 2004, at a staging area in the very same Charleroi, when I had a taste of the grim war being fought by Lance Armstrong’s minions. Totally by coincidence, I am reading the new book about the battle of Waterloo, by Bernard Cornwell. Another conqueror also passed through Charleroi that fateful month of June, 1815. His name was Napoleon Bonaparte. So now they are fused in my mind, the man on horseback, the man on the bike. As the Tour began in 2004, a new book came out, “L.A. Confidentiel: Les Secrets de Lance Armstrong,” by David Walsh and Pierre Ballester, containing many accusations of doping by Armstrong and his team. The book was only in French. I bought a copy at the Brussels Airport and was reading it as the Tour began in Liege. One of the most convincing sections was about an Irish masseuse, Emma O’Reilly, who recalled how Armstrong had tested positive for steroids in 1999, only to have a doctor file a note saying Armstrong had been using a form of steroids to combat saddle sores, an occupational hazard. If anybody knew whether Armstrong had saddle sores, it would be his masseuse, O’Reilly said -- and he did not. She described the panic in the Armstrong bus about the positive test, until a servile world cycling federation accepted the doctor’s ludicrous note, and Armstrong pedaled onward. I alluded to the negated positive. It did not go un-noticed. That drizzly morning in Charleroi, Armstrong’s lawyer-manager, Bill Stapleton, sought me out as we enjoyed coffee and croissants before the day’s stage began. He pointedly told me that Lance had never tested positive. Yes, he did, I said, for steroids. That was not a positive test, he said. I understood his legal point but more important I realized, these people are serious, and they are going to fight on every point. We all know how that ended, years later, with Lance’s confession on Oprah. I think about him while watching the Tour. I saw him win his last three titles. He was the greatest rider of his time. I suspect just about all of them cheated. I hear he has downsized, in his own private St. Helena. Napoleon also held a staging area around Charleroi, 200 years ago. He had come back from exile and had re-claimed much of the French army and was convinced his decisions would always work out. He would feint one way, go the other way, and rout the English and the Prussians. . But they stood up to him, in terrible fighting, on the road north in an area known as Waterloo. In July of 2004, I spent several nights in a motel near the battlefield but never had time to visit it. I was reading “L.A. Confidentiel” and riding in a press car with two copains and getting the cold eye from Lance’s perimeter defense. As a bicycle rider myself – wear helmet, obey traffic rules – I find it stunningly hilarious that in a city of human projectiles, ranging from clueless to murderous, the one amateur who gets busted is Alec Baldwin.

Of all the people to snag, the police happened upon the surliest New Yorker of us all, so charming in his old Capital One commercials, so crude when tossing homophobic slurs at journalists or screaming insults at his teen-age daughter. Of all the millions, why him, working his way through up Fifth Avenue, going against the flow? Needless to say, he smarted off to officers, got cuffed, back in May, and on Thursday he appeared in court in his old Capital One cuteness, to be called “Alexander” by the judge, and warned to be a “good boy.” How humiliating that must have been. But the real question is, what were the odds that police would get him, when just about every cyclist I ever see – and dodge – in Obstacle City is breaking one law or another? Living in a nearby suburb, I used to pop into the city on Sunday mornings, stick my bike on the back of my car, and ride around Brooklyn, Manhattan, even Staten Island one memorable time. It was great fun, at least til 10 AM or so, when motorists started gunning their engines. Now I drive and walk and take the subway all over the city but I don’t ride my bike in New York, nor would I rent one of those new clunky-looking things from this new fad called Citi Bike. In theory, making bikes available is a good idea – in Amsterdam, or maybe Seattle. But in New York, it only adds to the peril. It’s bad enough in New York dodging taxi and limo drivers – they are the worst, totally solipsistic – but cyclists in Manhattan are a close second. New Yorkers have multiple sixth senses for avoiding danger, and one of them is to instinctively know you are about to be splattered by a delivery guy, going the wrong way, or on the sidewalk, or busting the light. Death by sweet-and-sour soup. Messengers at least are professional assassins, speeding through lights, merciless, and some of them carry whistles to give you a fighting chance to save your life, and at least they are agile to avoid wrecking themselves. Now Citi Bike has put weapons in the hands of innocents. I did an unofficial survey the other day while parked in one of those weird new parking zones out in the middle of traffic. (What genius invented that?) I started counting merry cyclists playing in traffic and calculated that nine out of 10 – 90 per cent, doctor! – were not wearing helmets. As a driver and pedestrian, I fear the sight of adults, in their first minutes on a rented Citi Bike, teetering off the sidewalk, handlebars wobbling, no helmet, of course, with a goofy smile on their faces, no doubt recalling the last time they rode a bike, when they were 13, back home in Grover’s Corners, or at summer camp. Whoopee, let’s go play in traffic. It’s dangerous enough cycling in traffic if you obey the rules. On the peninsula where I live, I pause at signs, wait for red lights, and do not go down one-way streets. Some joker cut me off one time and the crossing guard near the post office screamed at him, made him stop, scolded him. Most drivers in my area are respectful. But ride a bike in Manhattan? Right in the middle of all this anarchy, perhaps holding a coffee cup in one hand – how New York is that? – comes Alec Baldwin, no helmet, riding up Fifth, as entitled as an actor with a stunt man ready to do the hard parts. To paraphrase his old commercials, what’s in your brain pan? In the last hours of the Tour on Sunday, I thought of the friend who taught me to love the sport.

So I went upstairs to get Roby’s old tricolor national-team jersey he gave to me after the Tour we shared in 1982. I hung the jersey by the television as I watched the riders make the normally ceremonial journey into Paris. I wear it only for special occasions – maybe a softball game or the five- mile Turkey Trot I used to run. I want the jersey to last. Roby Oubron was a four-time world cyclocross champion in 1937, 1938, 1941 and 1942, who was helping the Jonathan Boyer team during the 1982 Tour. Boyer had been the first American to race the Tour in 1981 – a forerunner to the Yanks who would later win the Tour. Roby was driving the car for Boyer’s manager Rob and photographer William and a Belgian camera crew (three guys known as Vandy). I was allowed to squeeze in for five days and immediately bonded with Roby who was squat and powerful and looked like Picasso. Although he had never ridden in the three-week road race that is the Tour, he had coached and mentored generations of French, Czech and blind cyclists – and was tight with Bernard Hinault, the Breton who would win the Tour that year. The car had access to the heart of the Tour. If I asked why Hinault was making a breakaway, Roby would gun the car alongside Hinault and chat with his pal, and then would report back to us in French simple enough for me to understand. Roby knew where to stop for a quick omelet during a long stage. He knew all the good bars for a quick beer in Bordeaux or the Pyrenees. He was at home with millionaire sponsors and rugged motorcycle messengers. He was one of the warmest, funniest, most communicative people I ever met. Roby had fought in World War Two, and had been injured and pulled off the battlefield by an American soldier. A few months after the 1982 Tour, Roby accompanied some Tour riders to a new race across Virginia – his first visit to the United States. I was in a car with him when we saw the Washington Monument, and I saw tears roll down his cheeks. “J’adore l’Amérique,” he said. He became my adopted uncle figure; he and his lovely wife Simone watched over our daughter when she was working in Paris; he gave me a jersey that had been worn by French cyclists; and we met every so often in New York or Paris. “Tu es un champion du monde,” I would sometimes utter in dramatic fashion, and he would chuckle. Roby passed in the late 80’s; I never got to say goodbye. But every year when the Tour comes around, I think of the old cyclocross champion who never rode the Tour, but helped me love it. * * * On Sunday Bradley Wiggins became the first British rider to win the Tour and also dug up a great finishing kick to launch his countryman Mark Cavendish to win the stage -- a gripping end to this year's Tour. I celebrated the riders, the country, and Roby by putting on his jersey and hopping on my old-guy bike, and going for a spin. A morbid thought crossed my mind the other morning while I was transfixed in front of the tube.

No matter what, the Tour de France is going to end on Sunday with the ceremonial ride up the Champs-Elysées, and then it will go away for the next 49 weeks. Why does it have to go away? The Tour catches my attention like no other sports event; I’ve covered parts of six or seven, sometimes driving the course just before or just after the riders. Now I watch the live show on NBC Sports Network every morning (Tuesday is a rest day.) as the cyclists flit from mountain to coastline, from country to city, always something different around the next turn. The riders all look alike, with their thrust jaws and wraparound shades and wiry physiques hunched aerodynamically. For the viewer, the cyclists come to individual life through the expertise of Paul Sherwen and Phil Liggett, two Englishmen who have been broadcasting the Tour since humankind invented the wheel. They know all 198 riders registered for the Tour and, as the day’s race unfolds kaleidoscopically, they discuss which rider is a sprint specialist and which one a mountain man. One thing is certain: the Tour endures despite the retirement and current legal troubles of Lance Armstrong. Whatever he was doing chemically, we all saw him whup a bunch of riders who actually did test positive. He was a great force but he is long gone now. And the land and the riders remain. As seen by camera from a Tour helicopter, a knot of riders banks to the left around a curve on one rainy desolate section of country road. In the background are sheep or maybe one tent pitched in a field. A couple stands by the wayside, clapping politely. The mind snaps the picture and the camera rolls around the next bend. While the network breaks for a commercial, the camera may focus on a crumbling hilltop castle. Here is the ultimate truth about the Tour de France: the star of the show is one of the most beautiful and diverse and historic countries in the world. I know, I know, one does not need the Tour to drive through Normandy or down the Rhone valley or across the haunting Massif Central. (I tremble as I type that name.) For three weeks a year, the network brings France into my house. I try not to dwell upon that grim moment, coming next Monday, when the Tour goes away. Have we had enough of trying to un-do the past? I am referring to the expensive and futile trials of Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, whose cases are relevant to the ongoing pursuit of Lance Armstrong.

The charges against Bonds and Clemens ultimately failed because Major League Baseball allowed itself to be stonewalled by Donald Fehr and the Players Association long enough to avoid adequate rules and testing during the time of the steroids plague. By the same token, cycling was a swarm of corruption because every layer of that sport did not want to know – the Tour de France, the international federation, the sponsors, the media. Now the United States Anti-Doping Agency is going after Armstrong, who was beating riders who were ultimately caught cheating. Some of them are now giving testimony that Armstrong was the ringleader of cheating by his team. Some of the potential witnesses were loyal teammates of Armstrong. Their testimony could be important. But before going any further, USADA ought to look at the Clemens trial. The best thing Clemens had going for him was his accuser. McNamee was always a sleaze, even dressed up in a suit and tie for court or Congress, and he could never escape the aura of creepiness. The second best thing Clemens had going was the soft-minded indecisiveness of Andy Pettitte, his old buddy, who could not stay on message during his testimony. Pettitte probably received bad coaching from the same prosecutors who blew the first trial. They never had a chance the second time. The case should never have been re-tried. Nevertheless, we all pretty much know what Clemens is, a bully and a blowhard, and we have a pretty good idea that he cheated. Now he will be judged by time, and the public, and also by the baseball writers who vote for the Hall of Fame. The New York Times does not allow its writers to vote for awards in any field. If I did have a vote, I would not cast it for Clemens or Bonds because I have no doubt they juiced and lied about it. A whole generation – including Sosa, McGwire, Palmeiro and Canseco -- is going to be judged by this odd scruffy jury with long memories. Nobody likes being conned. One thing we have learned from these failed trials is that everybody needs to upgrade their laws and their senses to avoid the next round of plagues in every sport – doping, brain damage, gambling, sex abuse, corruption in American scholastic and college sports. Let’s fight the next battles. What’s your reaction? When I took the buyout from the New York Times last December, a few people asked if there was anything I regretted not doing.

I had to pause. I could think of a few legendary college football stadiums, a few arenas or ballparks, some great soccer stadiums in Latin America and Europe. But events? Then something popped into my mind: Paris-Roubaix. http://www.bicycling.com/news/pro-cycling/tom-boonen-powers-fourth-paris-roubaix-victory-equals-record If there was one unique sports event I had never covered, one exotic specialty I had not witnessed in person, it was the trek from outside Paris to the cycling-mad town near the Belgian border. The chief attraction is the roadway itself – multiple sections of cobblestones put in place during the Napoleonic Era, state of the art then, torture to human and machine nowadays. I have grown to love cycling, covering the last tumultuous years of Lance Armstrong’s reign. Some of my best days were spent in a car with Sam Abt, the Times’ long-time cycling correspondent, and James Startt, photojournalist and cyclist and musician based in Paris. James would drive, and Sam would smoke, and they would bicker over whether the CD would blare reggae (James) or punk rock (Sam, go figure). James is still plying his trade, as anybody can tell from clicking on Bicycling.com. He recently found one of the most obscure winners of the Tour, Roger Walkowiak of France, whose stunning upset in 1956 annoyed the French fans because (a) he had a Polish name and (b) he was not a favorite and (c) he employed tactics like preserving his strength by riding in the pack on key stages. No panache. Walkowiak made very little money from cycling but used it to buy a sheep farm in southwest France, and has remained mostly incognito ever since. Somehow, Startt cajoled Walkowiak into granting an interview that casts a deep look into the history and mentality of this fascinating sport. You can access it: http://www.bicycling.com/news/featured-stories/lamentation I was hoping my friend Startt, a former American cycling hopeful, would get to ride the Paris-Roubaix course ahead of the big race on Easter Sunday, but it didn’t work out. Instead, he and his camera were there when the cyclists arrived in the bustling oval in Roubaix. Also, the new NBC sports channel carried the last two hours of Paris-Roubaix, live, with the same phalanx of planes, motorcycles and cars used in the Tour, plus good old Liggett and Sherwen doing the commentary. I could sit in my living room and watch the best cyclists in the world try to avoid being maimed by the cobblestones of Flanders. That epic, singular race was described last week by John Leicester, the Associated Press European sports columnist. I won’t even try to go over his superb description and reporting: http://sports.yahoo.com/sc/news?slug=ap-johnleicester-060412 The sections are called pavés. I had seen them up close during one stage of the 2004 Tour de France, which meandered from Liege through the killing fields of World War One, and into France. I remember watching the team trial go past on a rainy, windy day, hardened Tour cyclists quivering from repeated shocks to spines and central nervous systems from hitting one 18th Century cobblestone after another. The cameras were so close you could see the reinforced bicyles shimmy and shake. It hurt to watch. The weather Sunday was cool and damp. People were bundled up along the narrow lanes, waving at the cyclists from inches away.(Why are there not more accidents?) I saw quaint villages and the green fields of Flanders in early spring. I was comfortable in my house, but could sniff the coffee and the frites. I would have loved to be transported to chilly Roubaix, listening to survivors grouse and marvel at this cruel test. I could only adapt the Passover saying: instead of Next Year in Jerusalem, I said, Next Year in Roubaix. It’s a thought. All men on racing bikes resemble Lance Armstrong:

Jaw and helmet and wraparound shades. On the most gorgeous Saturday in New York, Bare legs emerged from shorts, bikes oiled and pumped. My Trek Hybrid was hanging in the basement, So I plodded three miles on the track While cyclists churned on the main streets, Training for Paris-Roubaix, or lunch. |

Categories

All

|