|

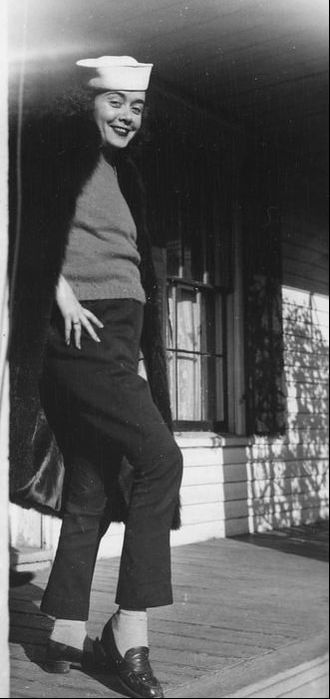

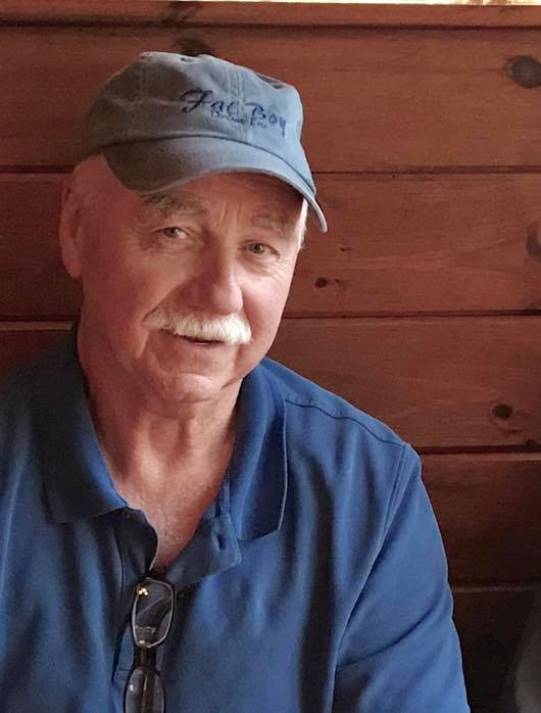

Thomas Friedman gives Mike Pompeo a well-deserved knee in his missing morality area. If you haven't seen it yet: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/18/opinion/mike-pompeo.html When I took ROTC in college, the first thing they did was pass out a slim manual about leadership, aimed at second lieutenants who might one day be in charge of a platoon, in combat. One of our teachers – can’t remember if it was an officer or a sergeant – defined leadership as: “Get the troops out of the hot sun.” Made sense to me. You want health and morale as high as possible. They taught potential officers how to speak to people. Make eye contact. Square up to the person you were addressing, whether standing or sitting. Try to know their name. Show respect. I left ROTC after three years – mutual decision, so I guess you could say, who am I to talk? I was married with a child before the Vietnam war heated up and I never served in the military. I knew people who never came back from Vietnam; I know people who graduated from West Point, who saw duty over there, who had classmates and soldiers under their command killed over there. I retain respect for the many things the military can teach via a slim manual. Some sports “leaders” have it; some do not. Other industries – no names mentioned -- could learn from the ROTC manual, or any kind of leadership seminar. A few years ago, an aged relative of ours was starting to decline in a very nice retirement home in Maine. My wife and I requested a conference with the director of the home, who had been an officer overseas, in the nursing corps. When we arrived, she stood up to greet us and asked us to sit down. She sat squarely in her chair and leaned forward for some small talk. “What’s on your minds?” she soon asked. I smiled and said: “I heard you were an officer.” Our meeting was productive. The retirement home did the best it could with our relative. I was reminded of that meeting on Friday, when I watched Marie Yovanovich, the former ambassador to Ukraine, face a Congressional subcommittee. (There may be something about this hearing in the media today.) This admirable American modestly discussed her long career, going to the front lines in danger zones, to fly the flag with the people who served. She talked about being caught during a shootout in Moscow as the Soviet Union came apart – being summoned to the embassy and having to make a dash for it without body armor. The only time the former ambassador seemed to falter was when she was asked why she was abruptly recalled from her top post in Ukraine. What had she done wrong? Did anyone explain? No, she said plainly. She would not venture a guess why. From the line of questioning from the Democrats, it was suggested that President Trump and his hatchet man, Rudy Giuliani, wanted her out of there, but never explained to her. The President gave others the impression that something bad could happen to her – beyond the blight to her outstanding career, that is. On Friday afternoon, Chuck Rosenberg, a sober legal counsel whom I have admired greatly throughout this ugly time, delivered what for him is a rant. Just back from a chatty day with friends in the city, I heard him (on Nicolle Wallace's hour), and I am sure that is what inspired me, five hours later, to deliver my own take here: One person was conspicuous by his general absence – the Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, No. 1 in the Class of 1986 at the United States Military Academy, who later served in Europe. At the Academy, Pompeo undoubtedly read leadership manuals like the one linked below. Probably, he looked after his troops when he was in uniform. But he is a civilian now – a former member of the House of Representatives, rumored to be interested in running for the Senate from Kansas, and currently punching his ticket by serving time in the cabinet, obsequiously. People have attacked somebody in Mike Pompeo's unit, have maligned her work. Did he assert his leadership? Perhaps he has been busy in some hot spot of the world, or perhaps he is cowering in his bunker at the State Department. Sometimes leaders have to deliver harsh news, harsh orders, to their troops. Mike Pompeo has never explained to the former ambassador to Ukraine why she was removed, does not seem to have thanked her for her service. Mike Pompeo has left Marie Yovanovich standing at attention, out in the hot sun, even when the President of the United States savaged yet another woman, in public, while she was testifying Friday. That is where we are these days. * * * "Expose yourself to many of the same hardships as your soldiers by spending time with them in the hot sun, staying with them even when it is unpleasant." --- Tacit Knowledge for Military Leaders; Platoon Leader Questionnaire. (below) https://books.google.com/books?id=BwXkyy-I_6EC&pg=SL1-PA12&lpg=SL1-PA12&dq=military+leadership:+Get+the+troops+out+of+the+hot+sun&source=bl&ots=OBao3XNlyM&sig=ACfU3U3oJCzEFsenoILmdI6OUsFn57HbPw&hl=en&ppis=_e&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiixoqPpO3lAhXhct8KHTXQA_IQ6AEwC3oECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=military%20leadership%3A%20Get%20the%20troops%20out%20of%20the%20hot%20sun&f=false Pg. A2 U.S. Army Cadet Handbook: https://www.unlv.edu/sites/default/files/page_files/27/ROTC-CadetHandbook.pdf My wife’s uncle, Harold Grundy, passed early Thursday at the age of 95. He was an American hero – a carpenter who learned complex engineering skills, who kept Navy ships steaming in murderous waters in World War Two and later supervised the building of observation stations and nuclear plants. He was a survivor – of bombs in the Atlantic and Pacific, of winters in the Arctic, a wartime storm off England, a typhoon in the Pacific, and of life itself. His only child Roger came home wounded from Vietnam only to die from a car wreck on a Maine highway. His wife Barbara was wracked by diabetes -- and he took care of her, with the help of dear friends. Everybody knew him in Bath, Maine, Barbara’s home town. After Barbara died in 2014, Marianne recognized the need to visit her uncle once in a while. At 93, Harold would have thick, rich chowder on the stove and fresh fruit pies baking in the oven. Harold would take us on little outings from Bath – beaches and fish restaurants and back roads. He took us to coastal towns that looked like a setting for “Carousel” and fish-fry stands and old forts. He talked about Barbara in the present tense: “Sometimes Barbara and I drive up this road in the late afternoon.”

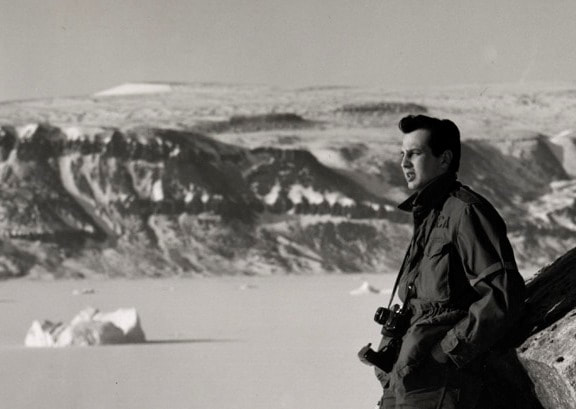

His education had ended in high school. He and his older brother left Connecticut in 1940 for a job dredging the Kennebec River to accommodate the large warships being built for what was coming. From his cottage alongside the river, he would tell us about rowing explosives into the middle of the river. In wartime, his acquired technical and engineering skills were essential to the military; he helped win one war and fight the Cold War. He was the last survivor who had served at observation posts in Greenland and Cutler, Me., and Guantanamo Bay, keeping an eye on our new best friends from Russia. However, because he was technically a civilian employee (ducking the same bombs as the military personnel), he was denied a pension by the U.S. government. Somehow, he was not bitter. Harold moved all over the world, building sensitive structures. Recently, we mentioned that one of our daughters lives near the nuclear plants at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. “Don’t worry,” Harold assured us, “I can tell you we made them double strong.” He had a Zelig-like way of being everywhere. He once chatted with a young senatorial candidate named John F. Kennedy in a train station in Boston; Winston Churchill popped out of No. 10 Downing Street and said hello to Harold and a few other tourists. One time we were driving near the coast and Harold casually mentioned he had helped build a house for Margaret Chase Smith when she was a senator. With her politician’s memory, she once recognized him when she got off a government plane at Cutler, and asked him to accompany her on her visit. People seemed to detect the civility and knowledge behind his humble bearing. He was so valuable to a construction company that they often flew Barbara to join him overseas, and they helped with her medical treatment. When Harold was home in Bath, between projects, he and Barbara, with her crippling diabetes, expanded a house on Washington St. He built houses and boats and docks and staircases for banks and chicken coops that were more handsome and sturdy-looking than some homes along the highway. Harold and Barbara started a little woodworking business – in their spare time, you understand – which has become a major business for a close friend. Harold and Barbara had a legion of dear friends who helped them: Cookie, Ace, Eric, Martha A, Martha B, Ann, Germaine, Diane, Rich and Suzanne, Bill, his nephew Dr. Paul, many caring medical people in the area, Kristi at the Plant Home, and people in shops and banks and drugstores, who fussed over them, in a real community. Two years ago, the Peary MacMillan Arctic Museum & Arctic Studies Center at nearby Bowdoin College held an exhibition of 193 photographs Harold took when he was based in Greenland. Harold’s family – including siblings in their 90s and late 80s – came in from New England and Florida for a reunion, in Harold’s most public moment. Harold came from hardy stock -- Quakers named Watrous and Crouch and Whipple who settled the eastern Connecticut coast and people named Grundy and Clegg and Schofield who thrived in Lancashire during the Industrial Revolution. But even these rugged folk wear down. Harold was fading the last time we saw him, on his 95th birthday in September. He had moved into a lovely retirement home, but his energy was gone and he could not enjoy the party. On Wednesday night, Cookie, a surrogate daughter to Harold and Barbara, who supervised their paperwork, was visiting from Connecticut, to be near him. Harold passed as a wintry storm roared up the coast. Come spring, Uncle Harold will be interred in the lovely hillside cemetery where he used to take us to visit Barbara and Roger. In recent weeks, as I thought about Harold and Barbara and Roger, my mind moved to a song about the release from pain – “Agate Hill,” by Alice Gerrard, recorded by the great Kathy Mattea. As I type this in the snowstorm, I think of Roger and Barbara and Harold together, building and cooking and fishing on some celestial version of coastal Maine, and I hear a line from the song: “Wild and free again, oh it will be as then.”  IN MEMORIAL, GERMAINE BOYNTON Harold often talked about his in-law Germaine who lived further up US 1. She invited us to lunch last spring and cooked a French-Canadian specialty and showed us the work and studios of hers and her daughter Diane, two formidable and artistic ladies. Germaine passed in hospice Saturday morning, two days after Harold. All through this long holiday period, I have been thinking of people who set an example for the rest of us.

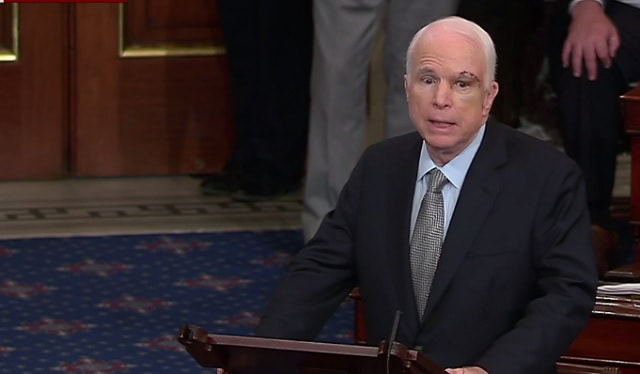

Now I wish I had not found this one. In the final week of an unsettling year, a young soldier – an immigrant, yes – risked his life once, twice, three times, four times, to save people in a horrendous fire in the Bronx. And then he went back a fifth time and did not survive. A week before, I had filed my final post of the year -- a reminder (to myself) to light a candle rather than curse the darkness. (Whole lot of cursing going on.) Emmanuel Mensah from Ghana personified the selflessness we all like to think we could demonstrate, if we had to….if it presented itself…. I came up with other examples, people I actually know. My friend Mendel of Jerusalem is a rabbi and family therapist (and writer, and runner, and Mets fan from Queens) who volunteers as a counselor with EMT units. We met for lunch on Long Island during his home visit. He told me that while trained medics deal with the physical part of a crisis, Mendel finds anybody who needs support. He never knows what language or accent he will hear when he takes somebody’s hand. They could be Jewish or Muslim or Christian. He does not care. He ministers. He lights the candle. Then I thought about my wife’s uncle Harold from Maine. He recently turned 95 and can no longer have home-made fish chowder and pie waiting for us when we drive up U.S. 1. Harold says he would like to be “with family” – aging, scattered -- but his “family” is right there in Bath, where he has lived most of his life. There is Ace, a surrogate son who returns regularly from the Southwest, and Cookie, a surrogate daughter who drives up from southern New England; they have skillfully handled the complicated details of a loved one who lives a very long time. There is Eric, whose family has been intertwined with Harold and his late wife Barbara. There is Martha, who drives Harold to the doctor even as she works full-time. There is Ann, the friend and nurse who has given diligent counsel. There is Germane and her daughter Diane, and Rich and Suzanne, and Bill, an in-law, and Kristi, retired Army colonel and nurse, who watched over Harold in a lovely retirement complex, as long as it was feasible. We have witnessed the best example of a classic American town, actually bustling with work (building warships on the Kennebec River, which Harold dredged in 1941) and the good will of people who know who they are, where they are from. But let’s double back to Emmanuel Mensah, from Ghana. The Times says he joined the Army National Guard and recently passed basic training. He planned to go on active duty, but before he did, there was a fire in the building. At the end of a dark year, I visualized Emmanuel Mensah’s military training – the preparation to protect people, to back up your buddies, to serve. In the months to come, I count on that developed impulse to follow rules. I suspect Emmanuel Mensah’s fine instincts as a human being, from his homeland of Ghana, were encouraged by the American military: when bad stuff is happening, go toward it. Emmanuel Mensah, an immigrant, saved lives in his final minutes on this earth. In the new year, his example shines. (Above: the good old days for the Trump-Flynn axis.) He continued to make a fool of himself in public this week with crude comments in front of hallowed veterans and ignorant tweets using fraudulent posts, disturbing our closest allies. More and more people are speculating that President Trump is showing signs of dementia or some kind of breakdown. Now his legal problems are at his front door, with the news that Michael Flynn has pleaded guilty to lying to the F.B.I. and is likely to sing about the few people who were above him in that sordid chain of command. Meantime, the Republicans are following their eight-year vilification of Barack Obama by ignoring disturbing behavior by their guy. Trump is their meal ticket to taking money away from most of America (including the deluded folks who voted for him) and, patriots that they are, they are going to ride him as long as he is in office. Remember: I speculated he would be gone within 18 months. I could write a post about North Korea -- or the football Giants humiliating Eli Manning and not living up to Mara family loyalties – or how bright the moon is in very late autumn. But what else is there but the menace in this "administration?" (This is what I wrote earlier in the week:) He debases the nation every time he opens his mouth. On Monday there was a ceremony honoring three surviving members of the Navajo Code Talkers from World War Two. The President of the United States used the occasion to take another jab at Sen. Elizabeth Warren, once again referring to her as "Pocahantas." (He is currently trying to destroy the consumer protection agency she helped create.) His disturbed behavior drags us all down. Even while the leader of the Navajo group was giving a stirring history of the unit -- which saved lives during the Pacific campaign -- he fidgeted on the sideline, his facial tics reminding us that he is always nervous when the talk is not about him. What a contrast between loyal Americans who sacrificed for all of us -- The Greatest Generation -- and a schemer who wants to make this a better world for the Mnuchins and Wilburs and Ivankas -- The Gunnysack Generation. (This piece was written 12 hours before John McCain cast a deciding vote in defeating the bill that would have taken health care from over 20 million people. I have read Paul Krugman's perceptive column in the NYT, also written earlier Thursday, long before McCain's vote, depicting the senator's erratic stances.

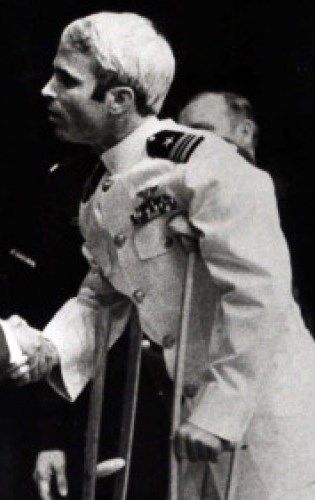

It's tricky to write about a moving story. On Thursday, Laura Vecsey wrote a glimpse of the Scaramucci family from our town. Later, Anthony became Trump's Trump via his vile rant to the New Yorker. It's a moving spectacle. I think I know where this is all going -- sooner rather than later, one can only hope. GV.) * * * This is not the role anybody wanted for John McCain – appearing in public with a red raw line above his eye, from the recent incursion toward his brain. I have been writing for over six months that I fully expected Sen. McCain to be a pivotal figure in the inevitable dumpsterization of Donald Trump. I spent a few hours with Sen. McCain in his office for a column during an Olympic hearing in 1999, seeing the cranky side and the generous side. Sen. McCain remains enigmatic – coming back from an awful diagnosis to cast a vote on health care, temporarily siding with the president who once declared him not a hero, and also supporting the amoral Mitch McConnell, to prolong this foolishness. But then John McCain did what I have expected of him on his good-John-McCain days: he plainly called the Republican health-care “plan” meaningless, empty. Now he has viscerally reacted to the pathetic tweeter of the White House by criticizing the call to bar transgender people from the military. This pilot served, was tortured. He knows how things actually work in the service, as opposed to the poseur from military school. The same goes for Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who lost parts of her legs while serving as a pilot in Iraq. I saw her on TV the other night, talking about the foolish gesture toward transgender military people. She was, as always, so smart, so dignified. So presidential. John McCain did not get to be president. His best moment during the campaign was to take the microphone back from the bigot in red who labelled Barack Obama “an A-rab.” It was hard, recently, to watch John McCain stumble while asking questions in a Senate hearing. Now we know what is happening. But I am counting on him to exercise the just part of him. His pals in the mute White Citizens Council posse that materializes behind McConnell cannot pretend things are just fine, when John McCain is reacting viscerally to the disorder. Unlike Trump, Sen. McCain felt no need to pander to the religious right on the transgender issue. I originally thought it would take 18 rational months to rid the country of the buffoon, but now I think it could happen by Labor Day. This can’t go on. John McCain can help by calling out a disturbed man. He flew many missions, but when he and Lindsay Graham pay that visit to the White House one of these months, it will be John McCain’s greatest mission. On the Memorial Day weekend, it is only right to suspend hostilities and remember the people who served.

I’m thinking of the story Harold Grundy tells us every time we visit Maine. My wife’s uncle was a master carpenter working for the military during “the war,” mostly on ships delivering goods and ammunition. On one mission in the South Pacific, the closest ship was hit by a bomb or torpedo and split in two sections, both doomed. One half floated in his direction. “The men were on deck, waving to us,” he says. “They knew they were going down. The only thing we could do was wave back.” Think of it – dozens, perhaps hundreds, of doomed sailors, hailing their comrades. They all served. I think of two West Point football teammates who came home from Vietnam and discovered they had been serving (in different branches) way up north, during murderous fighting. Later, they learned the civilian government had figured out the war was not winnable, but did not bother telling anybody. “Their little epiphany,” one called it. He may be visiting the Academy this weekend, to honor classmates who died over there. I think of a man I did not know, a fraternity brother of sorts, buried in the military cemetery on Long Island. A friend of his from college visits the grave on the day he died in Vietnam, and organizes a scholarship in his name. I think of a journalist pal, Jim Smith, who served on the Stars and Stripes. For decades, he did not talk about Vietnam but now he has written a very nice book about what he saw, and gives the proceeds to veterans’ causes. I think about John Fernandez, the West Point lacrosse player who lost the lower parts of his legs in in Iraq --“bad day at the office,” he called it. Later, he played in alumni lacrosse games, on prosthetic feet and worked for veterans’ causes. I think about Tammy Duckworth, the pilot who lost parts of both legs on a mission in Iraq. She is now a senator from Illinois. I think about John McCain, who crashed in Vietnam and spent a few years in prison in Hanoi. I interviewed him once and told him my wife had learned McCain and his buddies quietly ran a pipeline of goods into Vietnam. Why? I asked him. His answer was a highly eloquent shrug with his broken arms and shoulders. * * * I think about heroes who served, not civilians who did not (like me), or ones who think people who get captured or shot down are not heroes, or ones who shove their way to the front of the pack and preen, as if they had done something mighty. This is the weekend for heroes. When Harold Grundy helped dredge the Kennebec River in 1941, he knew how deep the channel was, and where it ran.

Harold Grundy – my wife’s uncle – still lives alongside the Kennebec in Bath, Maine. Just a mile up river, the Bath Iron Works has just finished the newest and biggest American destroyer, the $4.4-billion U.S.S. Zumwalt. From the back window of his cottage, Uncle Harold has watched the behemoth on test runs. Recently, he read in the paper that the skipper of the Zumwalt, the marvelously named Captain James A. Kirk, was curious about the history of the dredging of the river. At 94, Harold remembers it all – how the workmen lived in modest cottages near the river, how he carried dynamite in a primitive pickup truck along a bumpy dirt road, lifting 100-pound packs onto a modest skiff and ferrying it out to ships, whose drill shafts went 90 feet deep, loosening thick slabs of rock. They went out in almost all weather, sometimes sleeping on board, helping dump the excess rock far out at sea. After the river was dredged, Harold worked for the Merchant Marines, ferrying ammunition, serving in murderous combat in the South Pacific as the ship’s carpenter, ubiquitously called “Chips” by the sailors for the sawdust and slivers produced by their labors. He saw ships blown to bits all around him, saw sailors on stricken ships waving a solemn goodbye as they went down. When the war was over, the Merchant Marine gave him a handshake but because he was technically a civilian he receives no military pension. Oh, well. He worked for the military for many decades, helping build high-security structures all over the world. Last year, nearby Bowdoin College honored him with a show of the photos he took in Greenland and other sensitive places. I wrote about it: http://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-heir-of-quakers-who-kept-his-country-safe Living alone since the death of his beloved wife Barbara, Uncle Harold read about Captain Kirk’s admirable curiosity and wrote him a letter, sharing the copious details in his memory. A few days later, Captain Kirk paid a visit to Harold's house, a mile from the Bath Iron Works, but Harold was out running errands. The captain left a unique gift -- a handsome peaked cap, dark blue with gold braid, and the name of the U.S.S. Zumwalt printed across the front. On the back was the name: Hal Grundy. Uncle Harold keeps it inside, in a large clear baggie. It’s not for all weather. The Zumwalt left Bath on Sept. 7, heading toward San Diego and points beyond. Uncle Harold will follow her progress, knowing that he helped get her from the Bath Iron Works out to sea. Well done. George Butterworth did not see himself as a composer. Rather, he was a well-rounded musician, who, like so many other privileged English men, enlisted in the military early in what they called The Great War.

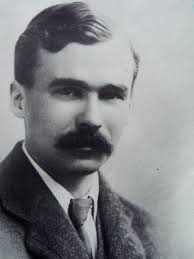

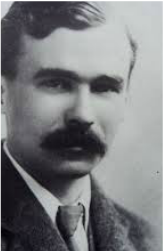

(I wrote the first draft of this a week before the Donald Trump Heel Spur controversy; of course, I did not serve in the military, either, having had two children young. George Butterworth did volunteer for the Great War, at the age of 29.) I never knew much about George Butterworth except as the first of three composers on a lovely Nimbus CD, “Butterworth, Parry & Bridge” -- three British composers, brought together in a 1986 recording by William Boughton and the English Symphony Orchestra. In my iPod, that arrangement blends into one long summer afternoon in the British countryside, idyllic, gentle, peaceful. It takes me back to afternoons when we used to visit a friend in mid-Wales. I paid more attention to the name Butterworth when it popped up in my wife’s ongoing genealogy study. One of her ancestors married a man named Butterworth in the 19th Century somewhere in Lancashire. It does not appear to be the same family, inasmuch as George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was born in London. His father was an executive on a railroad, who sent his son to the best schools—Eton and Trinity College, Oxford. After university, Butterworth traveled around England, sometimes as a professional morris dancer (there was such a thing in those days) and collector of folk songs. Sometimes he went around with Ralph Vaughn Williams, whom he prodded to expand a short piece into what would become his “London Symphony.” Butterworth expanded on the folk song, “The Banks of Green Willow,” and wrote music to accompany the poems of A.E. Housman in “A Shropshire Lad.” But "composer" was a label he resisted. In August of 1914, Butterworth joined up and was sent to the front, where armies were hunkering down in the fields of Belgium and France. He was made a lieutenant, put in charge of coal miners from Durham, with whom he had great rapport. He was shot once in the Battle of the Somme but recovered and went back to the trenches. On Aug. 5, 1916, George Butterworth was shot by a sniper. His body was not recovered but friends back home made sure his music was written down and survived the war. Ursula Vaughn Williams, the widow of the composer, kept Butterworth’s music in circulation. (I wish I had known that while watching that force of nature, Frances de la Tour, portray her in the recent movie,“The Lady in the Van.” ) “The Banks of Green Willow” has come to represent the people who died in the Great War. There is a Butterworth B&B in the French countryside, not far from where George Butterworth fell, a century ago, Aug. 5, 1916. George Butterworth did not see himself as a composer. Rather, he was a well-rounded musician, who, like so many other privileged English men, enlisted in the military early in what they called The Great War.

(I wrote the first draft of this a week before the Donald Trump Heel Spur controversy; of course, I did not serve in the military, either, having had two children young. George Butterworth did volunteer for the Great War, at the age of 29.) I never knew much about George Butterworth except as the first of three composers on a lovely Nimbus CD, “Butterworth, Parry & Bridge” -- three British composers, brought together in a 1986 recording by William Boughton and the English Symphony Orchestra. In my iPod, that arrangement blends into one long summer afternoon in the British countryside, idyllic, gentle, peaceful. It takes me back to afternoons when we used to visit a friend in mid-Wales. I paid more attention to the name Butterworth when it popped up in my wife’s ongoing genealogy study. One of her ancestors married a man named Butterworth in the 19th Century somewhere in Lancashire. It does not appear to be the same family, inasmuch as George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was born in London. His father was an executive on a railroad, who sent his son to the best schools—Eton and Trinity College, Oxford. After university, Butterworth traveled around England, sometimes as a professional morris dancer (there was such a thing in those days) and collector of folk songs. Sometimes he went around with Ralph Vaughn Williams, whom he prodded to expand a short piece into what would become his “London Symphony.” Butterworth expanded on the folk song, “The Banks of Green Willow,” and wrote music to accompany the poems of A.E. Housman in “A Shropshire Lad.” But "composer" was a label he resisted. In August of 1914, Butterworth joined up and was sent to the front, where armies were hunkering down in the fields of Belgium and France. He was made a lieutenant, put in charge of coal miners from Durham, with whom he had great rapport. He was shot once in the Battle of the Somme but recovered and went back to the trenches. On Aug. 5, 1916, George Butterworth was shot by a sniper. His body was not recovered but friends back home made sure his music was written down and survived the war. Ursula Vaughn Williams, the widow of the composer, kept Butterworth’s music in circulation. (I wish I had known that while watching that force of nature, Frances de la Tour, portray her in the recent movie, “The Lady in the Van.” ) “The Banks of Green Willow” has come to represent the people who died in the Great War. There is a Butterworth B&B in the French countryside, not far from where George Butterworth fell, a century ago, Aug. 5, 1916. Doug Logan, who is 72, recently slogged 22 kilometers with 22 kilograms in his backpack on a group run by military veterans. That number stood for the 22 vets said to commit suicide every day. The 110 men and women ran in silk skivvies, some did, to attract attention, not raise money. Logan wore red. Logan was the only runner who served in Vietnam -- 13 months as a forward observer with the 101st Airborne in 1966-67, earning two stars. Vets tend not to tell stories but I have heard a few allusions to the horrors of that mission, plus the challenges of returning to civilian life. Logan now runs a program for the homeless – many of them veterans -- near his long-time residence of Sarasota, Fla. I got to know him when he was the first commissioner of Major League Soccer in 1996, a bilingual sports executive (from his family roots in Cuba) who gloried in Valderrama and Etcheverry and Campos of the first years. Journalists are not supposed to be friendly with the people they cover – ask him about my snide remarks about low attendance and wretched teams in the early years in New Jersey -- but after Logan left that job we stayed in touch. So, yes, he is a friend. A year ago a city official in Sarasota proposed a job that Logan could never have imagined – come up with housing and programs for the homeless. After careers in entertainment and sports and other businesses, he was commuting to be an adjunct professor at New York University and loving a few days a week in the city, but the offer from Sarasota touched a nerve. “The best speech ever given is contained in two chapters of Matthew: the Sermon on the Mount. In those principles I hear the call to spend a part of your life doing good,” Logan told me. “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” – Matthew 5-7. Some residents of Sarasota fretted about Logan’s hiring, asking, are there not local people with proper degrees in social work? Others have questioned Logan’s departure from the national track and field federation but as a journalist I watched him try to abolish all drug usage, a sure way to become unpopular in that sport. As for his service in Major League Soccer, I could make the lame joke that anybody who took in itinerants like the ill-fated Nicola Caricola of own-goal MetroStar fame was practicing social work even then. But this is serious stuff. Logan is living up to the best lesson I remember from college ROTC: “Get the troops out of the hot sun.” That’s not in the Sermon on the Mount, but could be. Every year on March 3, a few aging fraternity brothers gather among the plain white headstones of Long Island National Cemetery to remember Walter W. Rudolph. He died instantly on that date in 1969, a first lieutenant rushing to rescue a fallen comrade in Vietnam. They talk for a while, and then Jerry Lambert, the organizer of the pilgrimage, reads a portion of the Gettysburg Address: But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate -- we can not consecrate -- we can not hallow -- this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. This is a recent ritual, less than a decade old. Every fallen member of the military deserves no less – friends who remember, friends who show up, mourning the early death, perhaps even shuddering at the ambiguities of that war. A friend of mine goes home to West Point every Memorial Day, visits the graves of classmates who died in Vietnam. I think he said the total is somewhere in the mid twenties. Showing up is important. Jerry Lambert remembers his friendly, open brother from the Upsilon Gamma Alpha fraternity at Hofstra University, who sometimes wore the olive R.O.T.C. uniform around campus. Lambert does not remember much controversy about Vietnam in 1963, although surely some people were beginning to question the war by then. He recalls that some members of the R.O.T.C. were “gung-ho,” but others, like Walter Rudolph, “saw the military as a way to serve, possibly a career. In those years, they weren’t thinking about going to war in Vietnam.” So Lambert never had The Conversation with his friend about why the United States was escalating the war in Vietnam. There was no shadow over their two years together on campus. Lambert was older, having left a seminary to enroll in Hofstra, learning he would have to take two years of R.O.T.C., surprised to find he could fire a rifle fairly well. Walter Rudolph was a psychology major, a member of the track and field team, a blocking back on the UGA touch football team that did well against the jock fraternities. “The girls liked him,” Lambert said. Rudolph had a visceral sense of humor, one time picking up Lambert’s leprechaun physique and holding him overhead, like modest free weight. “He came from the North Shore,” Lambert said, referring to Manhasset in Nassau County, whereas Lambert still lives in what he describes as a more modest section of Westbury in the middle of Long Island. His fraternity brother carried himself with a sense of assurance. Officer material. Lambert recalls his own mandatory trip to Whitehall Street, the recruiting center in lower Manhattan, immortalized in Arlo Guthrie’s Alice's Restaurant. A doctor, new to the military, told him he had a heart murmur and said, “You can go home now.” The enlisted men on guard collared Lambert at the door, and told him, wait a minute buddy, he had to go through the procedure. But within a few hours, he was officially out of the military. He assumes he would have served if cleared. Sometime in August of 1969, Lambert heard that his fraternity brother had been killed in action in Gia Dinh – then a separate city just outside Saigon, now incorporated into greater Ho Chi Minh City. “Why Walter?” Lambert remembers thinking. “That awful war got him.” Rudolph became one of the estimated 58,000 Americans killed in Vietnam. Hofstra put up a plaque to honor its dead on the former gym on the main quadrangle, and organized a scholarship honoring Rudolph and Stephen B. Carlin, another fallen Hofstra soldier from that era. A decade ago, Lambert suffered through a personal depression, but he came through it. One day he and his wife, Judy, were visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial -- Maya Lin’s Wall in Washington, D.C. He had heard criticism of the undulating wall, set pretty much below surface level, like entering some other world, and he was prepared to hate it. Instead, he instantly felt it was one of the most beautiful monuments in the world. He found his friend’s name, placed his fingertips on it, and “somehow, Walter’s name started to transform me. I could feel my self-involvement start to go away.” Lambert, 71, and his wife operate their own company, bicycleposters.com, and frequently travel to cycling events, including charity rides organized by the Lance Armstrong Foundation; a cousin of his died young of cancer. He is something of an organizer. Sometime around 2003 or 2004, he rounded up some other old members of UGA, which has since been folded into TKE, a national fraternity. “I was embarrassed at not doing this thing sooner,” Lambert said. The visit to the cemetery usually includes Bob Gary, Frank Pittelli, Paul Koretzki and Tony Galgano, all fraternity brothers from the early 60’s. The white headstones stretch in all directions on the flat earth of central Long Island. Many have crosses; some have the Star of David. Some service members died in action; others died in old age; some spouses are buried alongside them. The cemetery is plain and utilitarian, with few flowers or stones or other decorations, at least in late winter, but the cemetery is inclusive in the best sense. There is no politics, no history, no judgments. When Lambert escorted me to his buddy’s headstone last week, I kept hearing the mournful voice of Johnny Cash, the American icon, who would have turned 80 on Feb. 26. In his classic Vietnam song, Drive On, Cash wrote: He said, I think my country got a little off track, Took 'em twenty-five years to welcome me back. But, it's better than not coming back at all. Many a good man I saw fall. And even now, every time I dream I hear the men and the monkeys in the jungle scream. Drive on… Americans are getting the hang of welcoming our people back. I’ve seen Vietnam guys at recent military funerals I covered – not quite regulation uniform, longish hair, letting their freak flag fly, the air of the outsider still with them. Drive on… Maybe soon New York City welcomes back the men and the women from Iraq, and after that from Afghanistan. Out on Long Island, on the anniversary of Walter Rudolph’s death, Jerry Lambert and his brothers will stand guard. * * * Note Below: Cash's version on American Recordings has way more kick to it: |

Categories

All

|