|

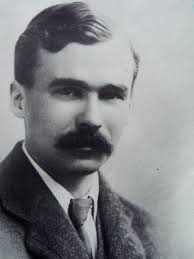

George Butterworth did not see himself as a composer. Rather, he was a well-rounded musician, who, like so many other privileged English men, enlisted in the military early in what they called The Great War.

(I wrote the first draft of this a week before the Donald Trump Heel Spur controversy; of course, I did not serve in the military, either, having had two children young. George Butterworth did volunteer for the Great War, at the age of 29.) I never knew much about George Butterworth except as the first of three composers on a lovely Nimbus CD, “Butterworth, Parry & Bridge” -- three British composers, brought together in a 1986 recording by William Boughton and the English Symphony Orchestra. In my iPod, that arrangement blends into one long summer afternoon in the British countryside, idyllic, gentle, peaceful. It takes me back to afternoons when we used to visit a friend in mid-Wales. I paid more attention to the name Butterworth when it popped up in my wife’s ongoing genealogy study. One of her ancestors married a man named Butterworth in the 19th Century somewhere in Lancashire. It does not appear to be the same family, inasmuch as George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was born in London. His father was an executive on a railroad, who sent his son to the best schools—Eton and Trinity College, Oxford. After university, Butterworth traveled around England, sometimes as a professional morris dancer (there was such a thing in those days) and collector of folk songs. Sometimes he went around with Ralph Vaughn Williams, whom he prodded to expand a short piece into what would become his “London Symphony.” Butterworth expanded on the folk song, “The Banks of Green Willow,” and wrote music to accompany the poems of A.E. Housman in “A Shropshire Lad.” But "composer" was a label he resisted. In August of 1914, Butterworth joined up and was sent to the front, where armies were hunkering down in the fields of Belgium and France. He was made a lieutenant, put in charge of coal miners from Durham, with whom he had great rapport. He was shot once in the Battle of the Somme but recovered and went back to the trenches. On Aug. 5, 1916, George Butterworth was shot by a sniper. His body was not recovered but friends back home made sure his music was written down and survived the war. Ursula Vaughn Williams, the widow of the composer, kept Butterworth’s music in circulation. (I wish I had known that while watching that force of nature, Frances de la Tour, portray her in the recent movie,“The Lady in the Van.” ) “The Banks of Green Willow” has come to represent the people who died in the Great War. There is a Butterworth B&B in the French countryside, not far from where George Butterworth fell, a century ago, Aug. 5, 1916.

Brian Savin

8/5/2016 07:08:12 pm

Thank you, George, for making the introduction. Allow me to share some vocal settings to four Henley poems he composed that I've found and we are enjoying as I type this:

George Vecsey

8/6/2016 01:15:52 pm

Brian, thanks for the recommendation. The baritone has a nice voice. There is such a pastoral feel to the poems and the music --1911-12, before all hell broke loose. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|