|

There is only one way to ponder family genealogy -- with humility, knowing that others do not know their distant past.

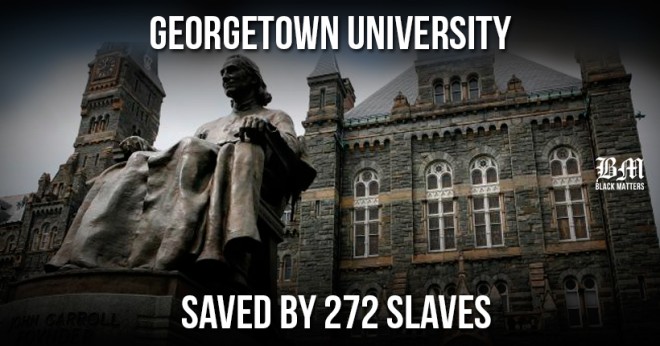

That lesson is brought home in Saturday’s New York Times, with its touching article on descendants of 272 slaves who were sold by Georgetown University in 1838 to keep that school solvent. In the article, four people in Louisiana talk about the trail of slavery with the grace of survivors, through strong families as well as the influence of the very same Catholic Church that sold them in 1838. In no small way, religion seems to have helped them, given them strength. That is the paradox. Their words, their wisdom, are a lesson to many people, including me and my wife, who can trace parts of our families back for centuries. We often feel humility toward in-laws and friends descended from Africa, as well as our Jewish friends who listen with kindness and curiosity when my wife talks about her genealogy research. We know of the gaps and absences in many lives. I can relate to some small degree because my father was adopted by a Hungarian family, his birth records sealed and apparently later destroyed by a fire in New York City. We only know his name when he was placed in an orphanage. I have always assumed he was part Jewish. I can live with that mystery, knowing of my mother’s maternal side back to County Waterford in Ireland (hence my treasured Irish passport.) My mom’s Belgian-Irish cousins were heroes in Brussels during the War.) My mother’s paternal side, Spencer, goes back to Leicestershire and later to Australia and back to England again before immigrating to the U. S. My wife has been digging into her roots in England, with help at the Mormon center in London, and lately she has been going on line into village records, as well as an ancestry web site. Over the years she has also taken information from relatives, including her grandfather, before he passed, and to this day from aunts and uncles still going into their 90’s. (Childhood farm living, no smoking, no drinking, equals longevity.) Her grandmother’s side comes through a branch of English Whipples who came into Rhode Island around 1632 and moved down to Ledyard, Conn., mingling with people named Rogers and Crouch and Watrous, many buried in the Quakertown cemetery. Her grandfather’s side traces to around Rochdale, Lancashire, in the 16th Century, with names like Grundy and Clegg and Schofield and Heywood. My wife – who spells her name Marianne – notes that many of our English ancestors had the same names – Mary Ann, Sarah, Elizabeth, Edith, George, Frederick, Arthur and John, a million Johns on my wife’s side. Sometimes she says we could be related. Aren’t we all? We have inherited little, except names and genes and mystery, along with a sense of being part of something. My wife – who loves India deeply; has been there 13 or 14 times – was told by her grandfather that a female ancestor, Sarah Schofield, had ridden an elephant in India while her husband was posted there by the colonial army in the 19th Century. She feels kinship over two centuries. None of this means much, except a sense of heritage. My wife’s people could make things with their hands; they were church-goers, people of peace, some of them abolitionists. She is still ripping mad that Spielberg’s movie, “Lincoln,” showed a Connecticut senator voting for slavery. History becomes personal all over again when we read the article by Rachel L. Swarns and Sona Patel in the Times about the good people of Louisiana, who want some tangible memorial to the 272 ancestors who were sold by a college. As we read the quotes in the Times, we feel sadness that others do not have the same reassurance of ancestors, of place, of choice, of freedom.

Brian Savin

5/22/2016 05:53:54 am

Genealogy for me has always invoked the wonder and motivations of movement. Why would someone book passage on a ship to travel to some different universe? What was going through their heads? I look at myself who won't book passage on a plane these days until the silliness and dispairing hardships of airport so-called security disappears, in comparison. Of course the slaves of the new world and prisoners sent to Australia have those questions well in hand. But we all wind up in the same place. Here we are. Now, how do we survive?

George Vecsey

5/22/2016 08:38:51 am

Brian, there was a story in the NYT the other day about Americans staying closer to home, not moving as much.

Brian Savin

5/23/2016 09:42:15 am

Geneology: boats and wars.

George Vecsey

5/25/2016 05:03:04 pm

Brian: sorry to be slow in responding. Depends how you define fighting. Marianne’s uncle Harold Grundy – I wrote about him a few months ago as the Quaker who helped build American nuclear facilities – was reputed to be a C.O. in WWII, but he insists he was not. He was a civilian expert on logistics. (Hence, no govt pension, a scandal, if you ask me.) He didn’t fight., He merely worked on ships near shore, arranging for jeeps, trucks, weapons, etc. to be dropped near the coast. Those supply ships were sitting ducks. Many of his friends and colleagues were wiped out. He lives on, well into his 90s, a truly gentle man who did his service under fire. We are going back to Maine soon to hear more about it. Best, GV

Ed Martin

5/25/2016 12:14:39 pm

A always, thoughtful and touching an archetypal theme. Brian's note on ships calls up Peggy's father's line, Smiths, who seem to have arrived on a ship called "Increase" in the 1650 era, as I recall, perhaps earlier by a few years. However, no Smith is on the passenger list. A genealogy expert said that was not unusual, he/they may have been servants who were not listed by name. Her maternal grandfather, Ned Monahan, walked 80 miles at age 12 to find his way from "The North" to Philadelphia. (Some years ago we, joyously, found cousins in Fermanagh.). On my side, my Italian grandmother also arrived at 12, having left a village north of Genoa. Her, husband, second generation, was her Italian American language teacher.

George Vecsey

5/25/2016 04:55:22 pm

Ed, those early years are fascinating. Amazing what is now popping up on the Web, via Mormon research but also church records going digital and being scooped up by genealogy sites. Marianne making progress on some mysteries about ancestors. 5/26/2016 04:31:16 pm

George—Marianne has created a gem for your family that is fascinating to follow. 8/15/2016 04:27:42 pm

Hello. splendid job. This is a impressive story. Thanks for sharing! Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|