|

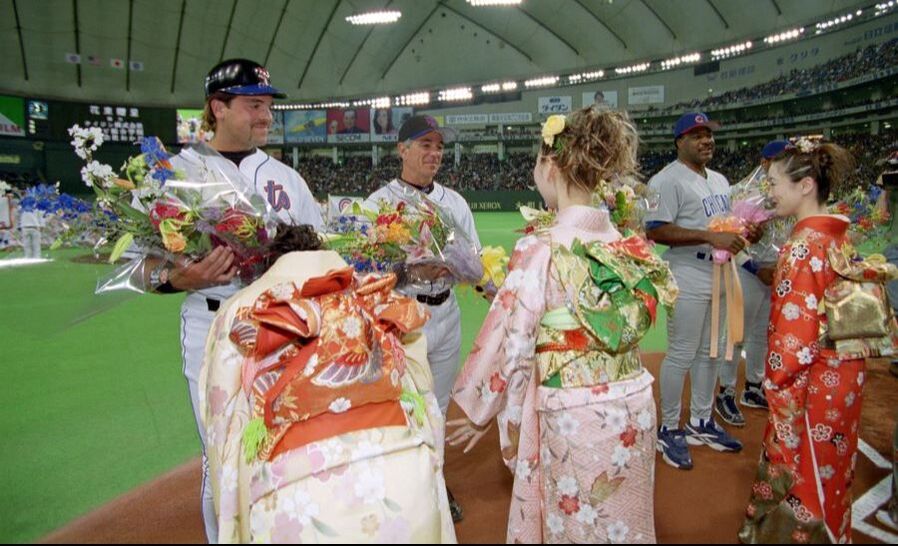

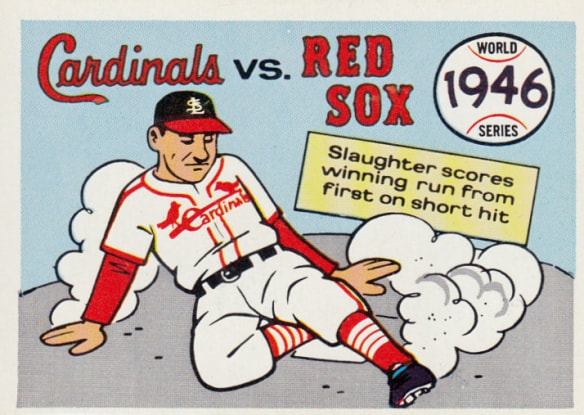

It was impossible to miss the sense of triumphalism in the Mets’ ballpark Saturday night, when Javy Baez made his debut – and clubbed a two-run homer that eventually helped the Mets win. We deserve this – so New York. The Mets’ fans celebrated this show of Steve Cohen’s money as the flashy rent-a-star for our times -- swing for the seats, strike out every-hour-on-the-hour, all condoned by the new analytics. But woven into the new math of baseball is the wholesale transfers of stars – the Cubs’ absolute gutting of players who won the World Series just the other day, or maybe it was 2016. The Nats' dispersal of players who won a World Series in 2019. Is there no loyalty, no sense of continuity, that lets stars grow old gracefully with their teams? Of course not. The players deserve their freedom. Curt Flood suffered for all of them, fighting for free agency, whether they know who he was, or not. You think the Brooklyn Boys of Summer would have stayed together if they had free agency? Imagine Duke Snider going for the big bucks and aiming for the right-field seats in Yankee Stadium before Roger Maris could. Word has just come to me that the Yankees have done it again -- bringing in Joey Gallo and Anthony Rizzo. It's an old habit: In 2012, I did a riff on late-season Yankee acquisitions over the years, with copious help and taunting from the late-great Yankee fan, Big Al, RIP. https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-yankees-always-get-somebody As a Mets’ fan – finally outed after decades of trying to disguise it as a sports columnist – I am queasy about the Mets’ move because I have been enjoying the Mets’ rickety hold on first place this season. I never believed the U.S. was getting back to “normal” with the murderous Covid, because I had a sour faith in the grits-for-brains mentality of the Red State no-vaccination crowd. (Did you see the Florida governor who scorns masks for school children because he wants to see the smile on his own child? Where do we get these people?) So, if you have to hunker at home, the Mets have been a nervous pleasure, with a shifting roster of office temps. Who will ever forget Patrick Mazeika, with his ZZ Top beard, a fill-in catcher, specializing in game-winning squibbers, getting his shirt ripped off in the new walk-off celebration? Who will forget Kevin Pillar surviving a pitch in the face, coming back quickly to patch holes in the Mets’ lineup? Patchwork players like Villar and Guillorme and Peraza and Drury helped the Mets stay in first place for roughly three months. The least of it has been the expensive addition of Francisco Lindor, with his .228 batting average, who appointed himself Leader-for-Life, interrupting pitcher-catcher confabs on the mound, inserting himself into every photo op, and now, upgrading his job status, apparently urging the Mets’ fill-in general manager that his pal Javy Baez would be a great addition. Maybe this is Lindor's best contribution to the Mets. But there is a school of thought that the Mets’ brain trust would have been better off finding a front-line pitcher to temporarily replace Jacob deGrom, who now has an endangered Koufaxian aura to him. But they went for the pyrotechnics. One Mets wing of my family paid for seats in Queens Saturday night and watched Baez (a) whack a home run and (b) do his on-the-field post-game interview with apparent joy at being in New York for the day and maybe even the long term. Is Baez a rent-a-star for this season, or will Steve Cohen pay the freight for a long-term contract, like Mike Piazza, who came…and stayed….and became a Mets icon? Or could Baez be like the magnificent Cespedes infusion in 2015? That was fun, too. I fret because Baez imperils my particular favorite Met player, Jeff McNeil, who seems terminally undervalued by the Mets’ front office. McNeil seemed to drink the Analytic Kool-Aid early this season, trying to launch Alonso-style homers, but lately McNeil has gone back to hitting the ball to all fields, with game-winning hits and a recent 16-game hitting streak – oh, and some flashy plays at second base in recent days. When Lindor’s oblique injury heals, he will claim shortstop and his pal Baez will apparently get second base. This leaves Jeff McNeil exactly where? Displacing the slumping Michael Conforto in right field (from which he unleashed a game-saving throw the other night?) What I’m saying is: old fans like me like old-style ball players, particularly the earnest Mets who have been a lot of fun this summer. But Baez certainly made a good debut Saturday night. (This just in: fan makes cheesy catch of home run ball.) * * * Clearly, baseball missed its fans as much as the fans missed baseball. Now we fully understand the pandemic pall of the truncated 2020 season -- no fanatics, no diehards, no leather-lungs, no lunatics, adding color and noise to the play on the field. Never again underestimate fans. Even with the modest percentile of fans allowed in ball parks in states where governments respect the murderous potential of the virus, baseball feels more like baseball this year. Fans with distended facial features and thrashing arms try to summon a rally. Fans stand and applaud a gallant catch, a timely hit, a strikeout pitch by the home side. Even back in our solitary dens, staying safe, we enjoy the game more this time around because some of our fellow fans are out there, doing what we do not yet dare to do – cheering, booing, beseeching, heckling, though their masks. Those fans are there for us. This was apparent Wednesday night as the Mets won their third straight game on a manic homestand. Some fans even displayed mid-season form in the skills of the game. James McCann, the experienced catcher who has already picked a runner off second base – first time in eight years for the Mets! – slugged a long fly ball to left field. Two Phillies made frantic runs to the wall, one digging his spikes into the padding, but the ball was over the railing – and into the glove of a fan in his socially-distanced position. The fan looked like a latter-day Mickey or Willie or The Duke as he softly squeezed the ball. Heroes all around us. Seconds later, a fellow fan applauded the catch, and the TV announcers duly noted the brilliant positioning and soft hands of the civilian. Better yet, somehow the Mets’ TV crew located his wife, Jessica, and their twin sons, celebrating McCann's first home run with the Mets. Last year that family moment could not have happened. Baseball has life again -- despite the mad-professor innovations in majors and minors: the goofus runner on second base in extra innings, the threatened extra foot from the mound to home plate, other silly little gimmicks in the fevered minds of Major League Baseball executives who apparently hate the game for which they are allegedly stewards.

But at least there are fans again – cheering, heckling, groaning, applauding. Some fans can even catch a major-league fly ball. Play ball!

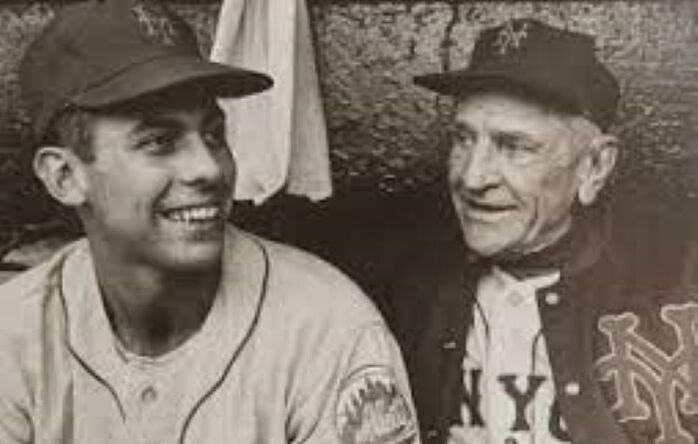

I learned the game from 1962 on, in the company of Casey Stengel, as he managed The Worst Team in the History of Baseball.

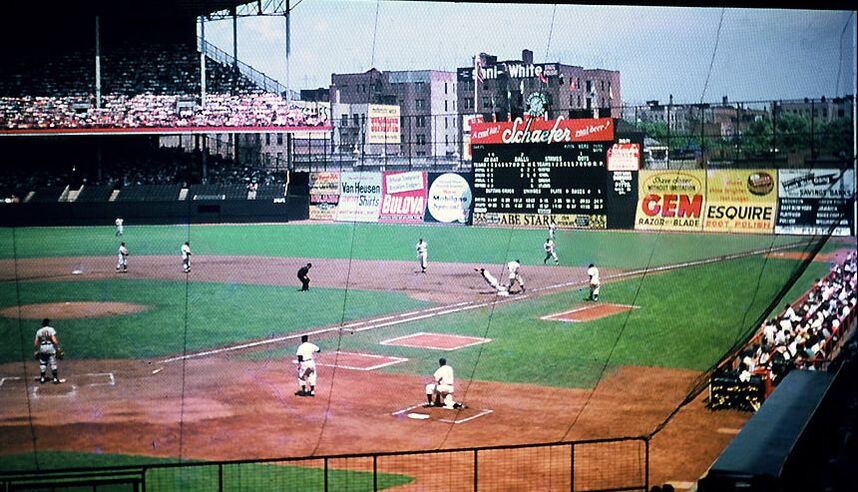

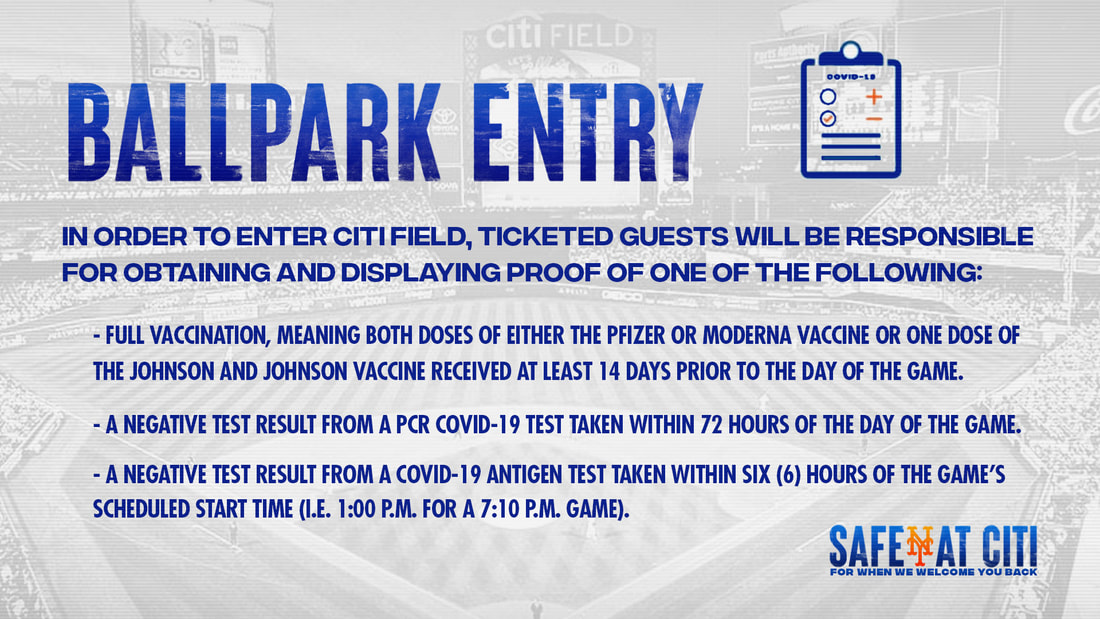

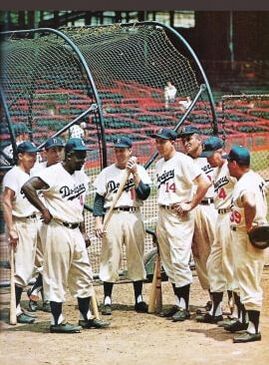

Casey's first young star with the Mets was Ron Hunt, tough country boy and master of getting hit by pitches. Casey knew the odds were stacked against the Mets. He said the umpires “screw us because we are lousy,” only he said it more graphically. So his Mets had to do something. He had a club rule – anybody who got hit by a pitch with the bases loaded would make $50. On May 12, 1963, Rod Kanehl, scrappy itinerant, took one for the team – and for his wallet – by managing to get hit by the Reds, scoring (NB: delightful Mets names about to appear) Tim Harkness, with Jim Hickman moving to third and Choo Choo Coleman moving to second. It is said that Rod virtually skipped on his way to first, laughing at the manna from heaven, or Casey, either way. How much would $50 be today? Kanehl’s protégé in 1964 was Bill Wakefield, rookie pitcher. Being a Stanford guy, Wakefield crunched the numbers the other day and figured the windfall for his late pal would be worth between $600-750 today. “We were all making $7K - $10K a year,” Wakefield wrote. Plus, the Mets went on to win the game, no small achievement then, or ever. Casey’s belief that you gotta do something was not lost on Ron Hunt, who used to wear floppy flannel jerseys a size or two big, so they would hang out and absorb a pitch. Hunt even dared the fates by getting hit by Bob Gibson, the surliest pitcher in the universe, and proud of it. Hunt went on to set a modern record by getting hit 50 times in 1971 (for Montreal.) Being around scrappers like Hunt and Kanehl and enablers like The Old Man, I still think it is part of the game to bend the rules until the umps wise up. One ump who may have wised up by now is Ron Kulpa, who ruled Conforto was legitimately hit, and the game was over, but later admitted Conforto had his arm in the strike zone and should have been called out. (Every sportswriter in American promptly dubbed him Mea Kulpa, obviously.) Having been around tough birds like Casey, Hunt, Kanehl and Gibson, I have some advice for the admirable Michael Conforto: in the next two games against Miami, you just might want to hang loose. * * * PS: Talk about mood swings: the Mets were down, 2-1, going into the bottom of the ninth. Howe Rose, on Mets radio, said he knows the mindset of Jeff McNeil, intense second baseman (when management leaves him alone) who was hitless in his first 10 at-bats this season. Take it from an old-timer, McNeil has some Rod Kanehl and Ron Hunt in him. Howie Rose said McNeil would try to pull a home run -- which he did, tying the game, prompting a celebratory bat flip, seen as bad form by opponents these days, Soon came Conforto's bases-loaded heroics. If I were McNeil, I also might want to hang loose in the next two games. * * * Rod Kanehl’s $50 plunking in 1963: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1963/B05122NYN1963.htm Lovely profile of Ron Hunt: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-year-ron-hunt-got-hit-by-50-pitches/  He hits. He fields. He pitches. Not his fault: He just doesn't win. He hits. He fields. He pitches. Not his fault: He just doesn't win. It took exactly eight innings for the 2021 baseball season to veer from glorious to horrendous. This is the lesson for Mets fans: Don’t get too chipper. We learned that in 1962 when the Mets loaded up with aging stars because, as Casey Stengel told us, he was expecting to make a run for the pennant. Ha! Record of 40-120 that year. It’s in their DNA. Two offspring and I were gloating, via smartphone messaging, in the early deGrom innings Monday evening. The Mets had missed the opening weekend because the Nationals had a Covid scare. Now Jacob deGrom was at his brilliant level, down in Philadelphia. * * * NB: A special treat in this article is a comment from JimH – otherwise known as Jim Henneman, longtime sportswriter in Baltimore. Jim assesses the career starts by Jacob deGrom, with the eye of a journalist with respect for stats as well as the emotion of the game. Please see Comments below: * * * Offspring 1 sent a snapshot off the tube, of deGrom throwing the ball past some hapless batter. Offspring 1 soon noted: “deGrom batting 1.000.” Offspring 3 added: “He was amped up.” Offspring 1 replied: “Wow. We may have to watch the Mets all season.” Not so fast. DeGrom threw 77 pitches in six scoreless innings and the three familiar TV broadcasters were at their best, attuned to his every pitch. But then there was a sighting of deGrom pulling on his warmup jacket and departing the dugout. Foreboding in the universe. We know how these things end. Before long, a collection of new culls and rejects was trooping out to the mound to collaborate on a 5-run eighth inning, with a defensive sub making a brutal error, and the Mets soon lost, 5-3, bringing us back to the defeatism from 1962 that is necessary to root for this team. New owner. New superstar. New faces in the bullpen. But same old rage. I’m sure there are fans of other teams out there -- in the only sport that plays every day, pandemic excepted -- who know instant disappointment. But Mets fans feel it is our birth curse. Jacob DeGrom is probably the best pitcher in baseball right now. He has won only 70 games in his career because a collection of geniuses has decided that even the best pitchers must be coddled and protected. In his short career, he has left a game 31 times with a lead that would be squandered. How does he not display the rage that bursts from Mets fans? A former Met I know, emailing sometime in the middle of the night, added his professional reaction to deGrom’s quick hook: “I know. I know. Protect the arm. Limit first start to 6 innings. We traded to get strong bullpen guys! “But opening day loss. 77 pitches! Wasted effort again. 31 times to the guy!! “Time for a little old school. Leave the guy in!!!????” Now the question is: whom do we blame for this oh-so-Metsian loss? Is it the fault of the analytics types who postulate that pitchers lose their edge the third time around the lineup? Is it the fault of a novice manager who doesn’t want to be remembered as the genius who burned out the star pitcher on a windy opening night in Philly? (The same young manager who somehow kept Dom Smith from hitting even once on opening night? Are the Mets suffering from a new ownership and a front office that has once again been assembled on the fly? I’m still repelled by having watched the Tampa Bay manager yanking his best pitcher in the last game of the 2020 World Series because, apparently, that is the way the game is played these days. Our little family web chain went all sour among us: Offspring 1: “We were all in!!! And now this!!” Parental Unit: “I hate this season.” Offspring 3: “Winter’s back.” I love this game. I hate this game. All on the same night. The cicadas are preparing to click and clack, as they do every 17 years: This Is The Year! Kind of like Mets fans. I can relate. (1969, 1986, for example.) But generically, baseball fans are way luckier than cicadas. We start buzzing maniacally every year at this time. I was planning a serious rant about baseball being taken over by the analytics mob, and how I don’t trust Major League Baseball after it arbitrarily trash-canned dozens of minor-league franchises. But with a potentially full season about to start on time, it turns out that great minds think alike: my incoming queue was full of Good Stuff from fans who actually know and care about the game. ---The first stimulant came from my friend Tyler Kepner in the NYT, when he reminded us that the National League is reverting to Real Baseball this season: that is, pitchers will hit. I was happy, thinking of Don Newcombe and Bob Gibson and Madison Bumgarner and other hitting pitchers, but Tyler raised this horrifying scenario of a great pitcher-athlete: “How would a Mets fan like it if Jacob deGrom shattered his fingers on a bunt attempt?” Good point, Tyler. I am now having second thoughts. --- The next missive was an email from Bill Wakefield, who pitched for the Mets in 1964, and we have remained in touch. He sent a link from the San Francisco Chronicle, which had three – count ‘em, three – savvy baseball columns by my esteemed colleagues Bruce Jenkins, Ann Killion and Scott Ostler. Scott’s column was about the two Bay Area managers -- Bob Melvin of Oakland and Gabe Kapler of the Giants, both contemporary guys who give thoughtful answers to reporters’ questions and would never, ever, spit tobacco juice on reporters’ shoes. Wakefield, who still trades Casey Stengel memories with me, wanted to know if I ever had a manager spit on my shoes. I replied, no, but Ralph Houk of the Yankees used to direct neat little sprays in the general direction of a colleague now and then. Plus, Herman Franks, the absolutely miserable manager of the Giants, (who liked to call reporters demeaning names in Spanish for the amusement of his Latin players) apparently couldn’t spit very far, but he did drool tobacco juice down the front of his undershirt or even his uniform shirt, apparently to hasten reporters to seek more sanitary interviews elsewhere. --- Next, Wakefield found a photo online of right field in Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Having briefly been a teammate of Duke Snider with the Mets in the spring of 1964, Wakefield wrote that after seeing the short porch in right field, he could understand why The Dook hated to leave Brooklyn. I told him how Casey had escorted a rookie named Mantle to right field before a pre-season exhibition between the Yankees and Dodgers in 1951, to show him how to play ricochets off the concave wall. Later, Casey told “his” writers that Mantle didn’t seem to process that Casey had once played right field in that very ballpark. “He thinks I was born old,” Casey said. -- Then, my man Mike From Northwest Queens sent me a copy of the Mets’ Covid rules for fans planning to attend a game under the 20 per cent limit this season: fans must present written proof of vaccination or a recent negative test for the virus. These rules reminded Mike of the iffy nature of going anywhere right now – sports events, restaurants, theatres, travel. Mike typed: “After reading this, I’m fairly positive I’ll be seated on my couch this year again for baseball.” I hear you, dude.  Notice Don Newcombe, rear right, hanging with the hitters. Pitching: 149-90. Hitting: .271 average and 15 homers. Notice Don Newcombe, rear right, hanging with the hitters. Pitching: 149-90. Hitting: .271 average and 15 homers. -- Ebbets Field lives in the souls of ball fans. The aforementioned Mike From Northwest Queens discovered this photo online of the Boys of Summer, standing around the batting cage, just talkin’ baseball. A glossy copy of this photo used to be taped in our house when I was a kid. Just seeing Jackie and Gil and the rest, I feel 12. ---Next, Lee Lowenfish, New York polymath on baseball, jazz, movies, et al, sent along a blog by Steve Wulf, longtime Sports Illustrated star, dissecting every name and reference in the Dave Frishberg jazz song -- elegant riffs about the long-ago Brooklyn pitcher with the mellifluous name of Van Lingle Mungo. Wulf’s treatise, with photos, is the reason the Internet was invented. He describes how Frishberg “plumbed The Baseball Encyclopedia for the names, some of which are delightful rhymes; Max Lanier and Johnny Vander Meer; Barney McCosky and Hal Trosky, Lou Boudreau and Claude Passeau." Frishberg chose the names for poetry rather than dismal analytics. May there always be music in the loving associations of baseball, now blessedly emerging from hibernation. * * * Steve Wulf’s long and loving assessment of “Van Lingle Mungo.” https://www.stevewulf.com/blog/mungo Ladies and gentleman, David Frishberg:  Michael Apted, young director Michael Apted, young director (I was gearing up to write something about my despicable ex-neighbor from Queens, who is trying to take the country down with him. Then I read the obits of two people who enriched my life, in several senses of the word, and realized I need to pay homage to Michael Apted and Tommy Lasorda.) * * * I was afraid of what Hollywood would do with Loretta Lynn’s book, and her life, and her roots in Eastern Kentucky. Having been the Times’ Appalachian correspondent, I was blessed to get to know her and be asked to write her autobiography, and have her tell me great stories that made the book “Coal Miner’s Daughter” so easy to put together. Then the book was marketed to Hollywood. From a vast distance, I heard rumors that this producer or that director wanted to put out a steamy version, a Beverly Hillbillies knockiff, of her colorful life. But then, way out of the loop, I heard that the Hollywood gods had lined up producer Bernard Schwartz….and screenwriter Tom Rickman….and British director Michael Apted. I exaggerate sometimes that when I say that I was invited to an early private screening in Manhattan and brought a fake mustache and a wig and a raincoat I could put over my head like gangsters do when they are arraigned. I did fear the worst. Then the movie began in the little screening room and I saw Levon Helm, as Loretta’s daddy, coal dust all over his face and hands, coming home from the mine and being met by his daughter, played by Sissy Spacek, and instead of goofus cartoon figures they were tender father and daughter, giving thanks that he had survived another shift underground. I could breathe. No disguises necessary. “The good guys won,” Rickman told me later. Michael Apted, best known for his “Up” documentaries, was a principal good guy. He has died at 79. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/movies/michael-apted-dead.html I got to meet Apted a few months later at the “grand opening” in Nashville, where my wife and I were treated like one of the gang. Levon, Sissy and Loretta (if I may call them by their first names) gave an impromptu concert at the hotel, and the next day “we” took a chartered bus up to Louisville. I chatted with Apted for a few minutes and told him how much I loved the movie, how fair it was to the region and how it lived up to what we had tried to do with her book. I still remember one sentence: “I am no stranger to the coalfields.” Later, I looked it up and saw he was born in posh Aylesbury and grew up in London, but the point was, Michael Apted was a serious film-maker who traveled and learned and listened. For a more distinct Appalachian feel, he incorporated some locals into the movie, just as Robert Altman did in the movie “Nashville.” I never met Apted again, but I am eternally gratefully to him and Schwartz and Rickman and the talented performers. * * * I knew Tom Lasorda better. I met him in the early 80s when he was already a celebrity manager with his monologues about “bleeding Dodger-blue blood.” He made it his point to know the New York sports columnists and including us as bit actors in his own personal production..

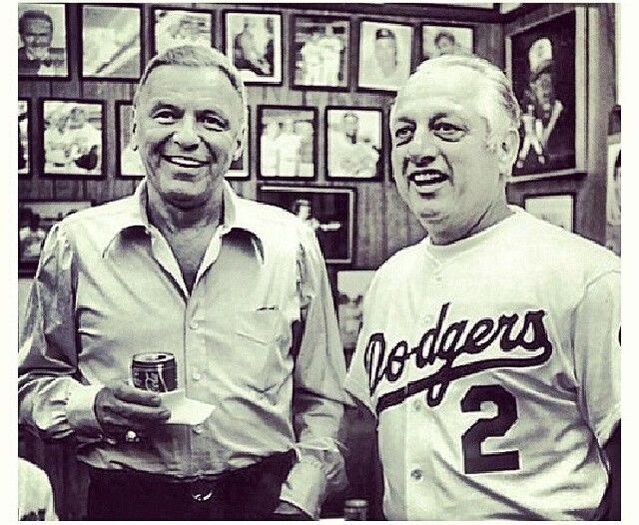

One time he told me that “Frank” had been at the game the night before. I guess I looked blank and he sneered at me and shouted, “Frank! Frank! Frank Sinatra!” Wherever he was, Lasorda’s clubhouse office might be home to show-biz or restaurant types, plus Mike Piazza’s father, Vince, Lasorda’s childhood pal. One time, in a big game in LA, the Dodgers had a lead in the late innings and there was a commotion in the dugout as Jay Johnstone ran out to right field and waved off some directive. Later we asked Lasorda what happened, and he said he tried to send Rick Monday out to play defense – a normal tactic -- but Johnstone had run past him, saying, “F--- you, Tommy, I’m not coming out!” Lasorda told it -- laughing, proud of Johnstone’s stand – particularly since it had not cost the Dodgers. I was working on a book with Bob Welch, the pitcher and my late friend, about his being one of the first athletes to go through a rehab center for alcoholism. I knew Lasorda had made a brief visit to the center during Bob's family week, and I wanted his recollections, but Lasorda was evasive. Finally, on the road, he agreed to talk to me in his hotel suite, blustering, raising his voice, as if somebody were listening in the next room. “He’s not an alcoholic!” Lasorda shouted. “He can take a drink or two! He just has to control it!” – totally against what recovering addicts know to be true. I will give Lasorda credit for giving me the time…and his point of view. Whenever we met, he always said hello. Whatever his personal life was like, he loved wearing Dodger Blue. In his bombastic showboat way, he incorporated peripheral types, like a New York sports columnist, into his world, and he made us enjoy our little part of it. * * * Richard Goldstein and Tyler Kepner have told many great tales of Lasorda’s life: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/sports/baseball/tommy-lasorda-dodgers.html?searchResultPosition=1 Sunday 6 PM: Since this post began as a praise to baseball for keeping me sane, let's stick with this post through the end of the Series....even with peregrinations to college rivalries (?) and uniform numbers and love of La Belle Province. My dirty new little secret: I couldn't watch Games 3 and 4 because I cannot stand the two Fox guys. They display no wit, no change of pace. In the day hours, my baseball lunch companions have been conducting a web seminar in scoring, fielding, analytics pro and con. Anyway, I am on for Game 5 Sunday evening -- and any ramblings that may ensue. GV  Freddie Freeman chatted up everybody, particularly Cody Bellinger Freddie Freeman chatted up everybody, particularly Cody Bellinger While waiting to see if the United States can save itself on Election Day, I needed something to fill my socially-distanced time.

Once again, baseball has come through – with a 60-game mini-season that allowed me to have a familiar sense of angst and rage about the Mets. Now there is about to be a World Series – with any luck, as taut as the two league series, seven games preferable to four – something to occupy house-bound fans like me. My first hope is that the network types will stop bombarding us with “post-season” statistics. First of all, give the computer a rest. Enough with the arcane stats. Second, we are about to enter what used to be called the World Series but now seems to be morphing into “the finals,” like the other endless post-season “playoffs.” True, the title “World Series” is a bit pretentious, even now with Latino and Asian players everywhere, but the title is baseball’s throwback to the days of two separate leagues that produced one champion each, to meet in early October. The leagues were different. Starting in 1947, the National League got a head start with the majority of Black superstars, and the American League had the Yankees stomping on their supine league rivals. Then, more likely than not, the Yankees won the World Series. Now baseball has blurred the rivalry between two leagues, but the separate identity of the World Series needs to be protected – including separate World Series statistics and achievements as homage to history, going back to 1903. So much else has changed in baseball. The recent series confirmed that the age of great starting pitchers has been terminated. Pitchers are interchangeable parts, no longer expected to go long. As Tyler Kepner pointed out, a pitcher can have a 3-0 lead in only 66 pitches and still be replaced by the parade of relievers, as Tampa Bay’s Charlie Morton was Saturday evening. That’s the way the Rays roll – right into the World Series. Most managers seem wired into the dictates of the analytics hordes in some bat cave under the ballpark. Hitters are encouraged to swing for a launch arc, not putting the ball in play in some open sector of the field. Something’s been lost. But I watched. And watched. As an alternative to endless sightings of a dangerous fool on the loose. And when the league finals came around, I found things to like about all four teams. I fell in love with Houston a few years ago, because of their charismatic players, before we knew the organization was systematically stealing signals. Now the Astros have become the team people love to hate. Did you see James Wagner’s great piece about the fan who hectors the Astros at high decibels? I get it -- the antipathy toward the Astros -- but Dusty Baker, age 71, a good human being who surpreisingly got to manage the Astros after the housecleaning, and I want him to win a World Series one of these years. Plus, I loved how Carlos Correa made clutch hits and showed leadership by lecturing his pitcher who was about to blow his top. I could not hate the Astros. However, the Tampa Bay Rays played the Mets late in the regular season and I acquainted myself with a willful group of mostly interchangeable parts, managed by Kevin Cash. Some of them could even steal bases and hit for contact, not distance – a throwback to real baseball. FAVORITE MOMENT AS SOME FANS WERE ALLOWED IN THE JUST-CONCLUDED SERIES: Justin Turner of the Dodgers picked up a foul ball -- and lobbed it to a fan in a distant seat. A sweet little custom, now revived I couldn’t choose between the Dodgers or the Braves, either. The Dodgers are the team of my youth, in Brooklyn. I love the uniforms and colors, although I have trouble seeing newcomers in blue Dodger trim. (Wait, why is Kiki Hernandez wearing Gil Hodges' No. 14?) The Braves are the retooled power in the same division as my second-tier sad-sack Mets, and I am jealous about their talent and leadership. The Dodgers had Mookie Betts making plays in the outfield. The Braves had Freddie Freeman, surviving an ominous case of Covid-19 and earning MVP honors – and chatting up any “opponent” who stopped at first base, including Cody Bellinger, the Dodgers’ star who would win the pennant with a home run late Sunday evening. (And dislocated his shoulder giving high-fives in the tumult.) Now the two survivors are going to meet in what sportswriters used to call “the old autumnal classic.” (And I just did it again.) Somebody, please tell the network yakkers: it’s the World Series. The first Yankee player I ever met was Whitey Ford, who died Friday at 91.

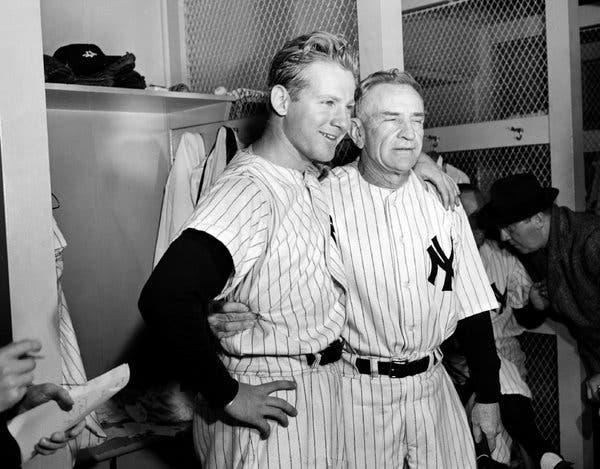

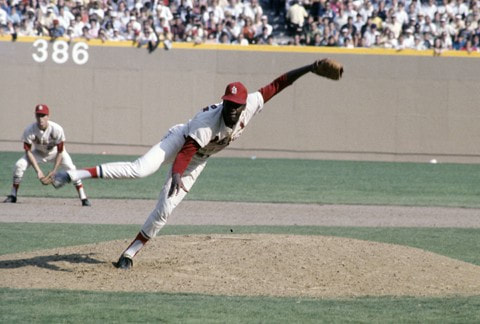

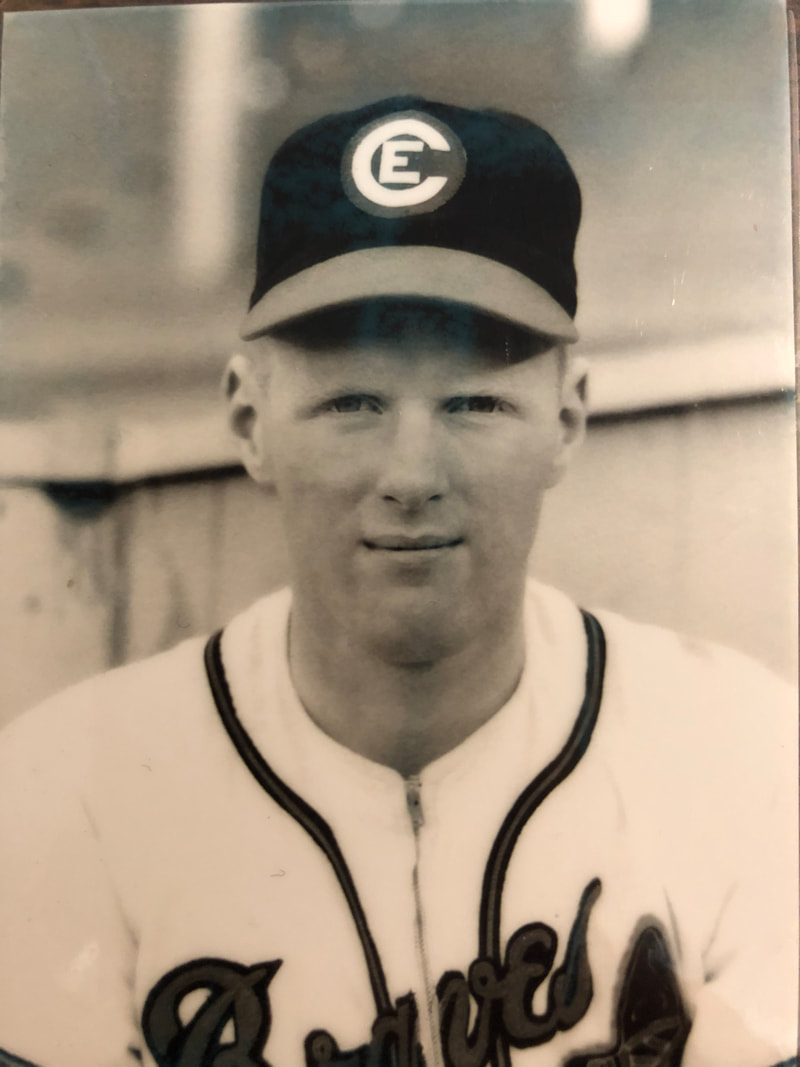

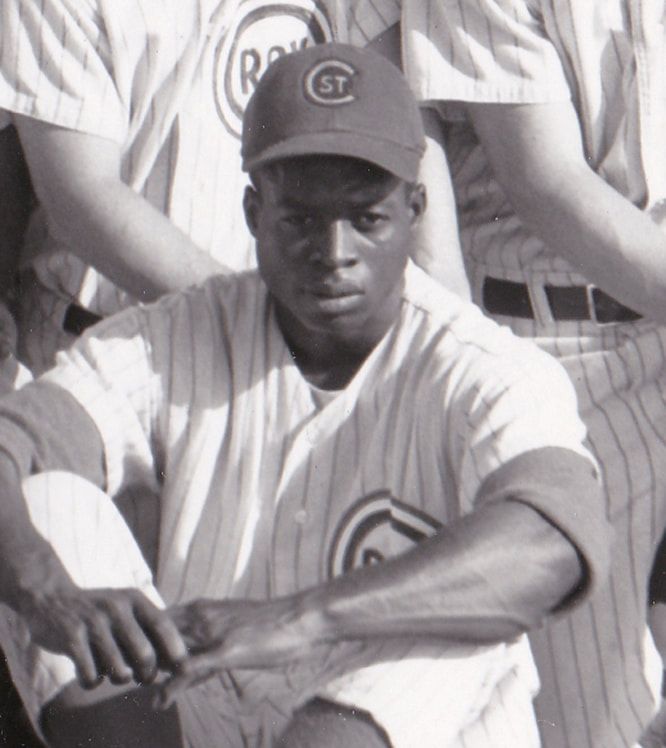

I was a kid at Newsday, the great Long Island paper, covering the high schools, and my mentors would occasionally take me to Yankee Stadium, the only New York ballpark open during what I call the Dark Ages. Either Jack Mann, the sports editor, or Stan Isaacs, the columnist, introduced me to Ford, in a corner of the clubhouse. Ford lived in Lake Success, just over the city line, and he was identified as “the crafty Long Island southpaw.” We wrote about him a lot because he was a great pitcher and because he was friendly. Not all the Yankee players were. I was not disappointed in the introduction. Whitey Ford offered his hand and fixed his alert eyes on me – a Queens guy, with accent to match. “Nice to meet you,” he said, and he made small talk, and I got the impression that I could talk to him, win or lose, and I was not wrong. For the rest of his career, Whitey Ford was available. He liked the coverage he got from his hometown paper, of course, but he also deserved it. For six of his first seven seasons, the Yankees won the pennant. I’m sure the Times and other papers will give proper respect to Ford’s marvelous career. I’ll stick to personal memories of Edward Charles Ford: --- When Ralph Houk replaced Casey Stengel in 1961, one of the first things he did was use Ford in 283 innings, the highest of his career. Perhaps Casey had been wary of Ford’s modest size, did not want to wear him out, but Ford became more of a workhorse through 1965. Houk rarely gave incisive answers to young reporters – known as Chipmunks because we chattered so much – but one day the manager visited Ford on the mound, as if to take him out, but instead he left him in, with good results. When we asked Houk later, he said: Whitey always told him the truth. If he was out of gas, he said so. If he still had something left, he said so. Houk’s answer seemed to me the ultimate affirmation of Ford, as pitcher and competitor and team player. -- Distinct memory of Whitey Ford from my first year or two: I cannot replicate it from the records, but I know I saw it: Two outs. Two strikes. A runner or two on base. My boss, Jack Mann, nudged me: “Watch this.” A hellacious curve broke in on the lefty batter, who lunged at the ball, as Elston Howard caught it – and sprinted to the dugout – as the visiting manager screamed bloody murder from the dugout steps. The manager said the ball had been doctored by Howard’s ultra-sharp belt buckle, but when asked later by intrepid reporters, Elston and Whitey knew nothing. Nothing. Ford's stuff and brain were enough on 99 percent of his pitches. He said it was Howard who named him "The Chairman of the Board." --- Ford was a good friend of Mickey Mantle, at all hours and all seasons – the city boy and the country boy. They called each other “Slick.” Ford would never try to explain his moody pal, but sometimes he could joke with Mantle, get him into a mood to talk to reporters. Life was so much easier that way. -- In those days, reporters traveled on the same charter flight as the Yankees – it made travel easier, and Newsday and the Times paid their own way, of course. The Yankee plane came back from Kansas City or Minnesota long, long after midnight, and at the baggage claim, I offered a ride home to Ford, and Hector Lopez, who lived on the way. I just needed to get my car in a nearby parking lot, while they guarded my suitcase. But when I got to my car, there was a flat tire – and my spare was shot – so I needed help. There were no cellphones in those days, kids, so I couldn’t notify Ford and Lopez that I was stuck. Needless to say, they – and my suitcase – were not at the terminal when I finally swung by. Okay. Next morning, at a reasonable hour, I got a call….from Whitey Ford….who said he had my suitcase at his house, and I could pick it up when convenient. That made him a major-league mensch in my book. May I just say that not every ball player would be as thoughtful. -- Ford’s body fell apart in 1966 and ’67 and he was sanguine about it. One day, in New York smartass humor, I jokingly called him “the game southpaw.” He twinkled as he corrected me: “the gamey southpaw.” But his career stats and his Hall of Fame stature smell like roses. -- Ford and Mantle were friendly with a chatty clubhouse attendant out of Fordham University named Thad Mumford, who was smarter and funnier than any ball player or any reporter, for that matter. Munford moved on, but at subsequent Old Timers Days, Mantle and Ford would spot him and the badinage would pick up, all over again. One year, Mantle drawled, “Hey, Thad, would you get me a beer?” Ford, with city-cat patronization, advised Mantle, “Hey, Slick, Thad writes for “M*A*S*H,” and Mantle blushed beet-red, as he sometimes did. Munford loved it – and went to get a beer for his old pals. Mumford would have occasional bouts of nostalgia out in California, and would call some old-time contacts. Thad passed two years ago; he counted Ford as one of his best Yankee friends. Now the Chairman of the Board is gone, but his records remain, and so does the twinkle from a friendly corner of the long-vanished Yankee Stadium. * * * https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/09/sports/baseball/whitey-ford-dead.html https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/fordwh01.shtml Bob Gibson passed Friday of pancreatic cancer.

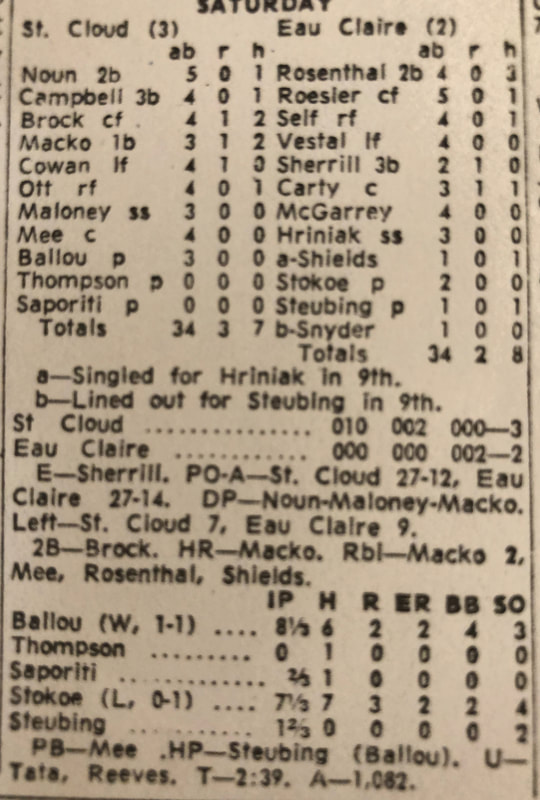

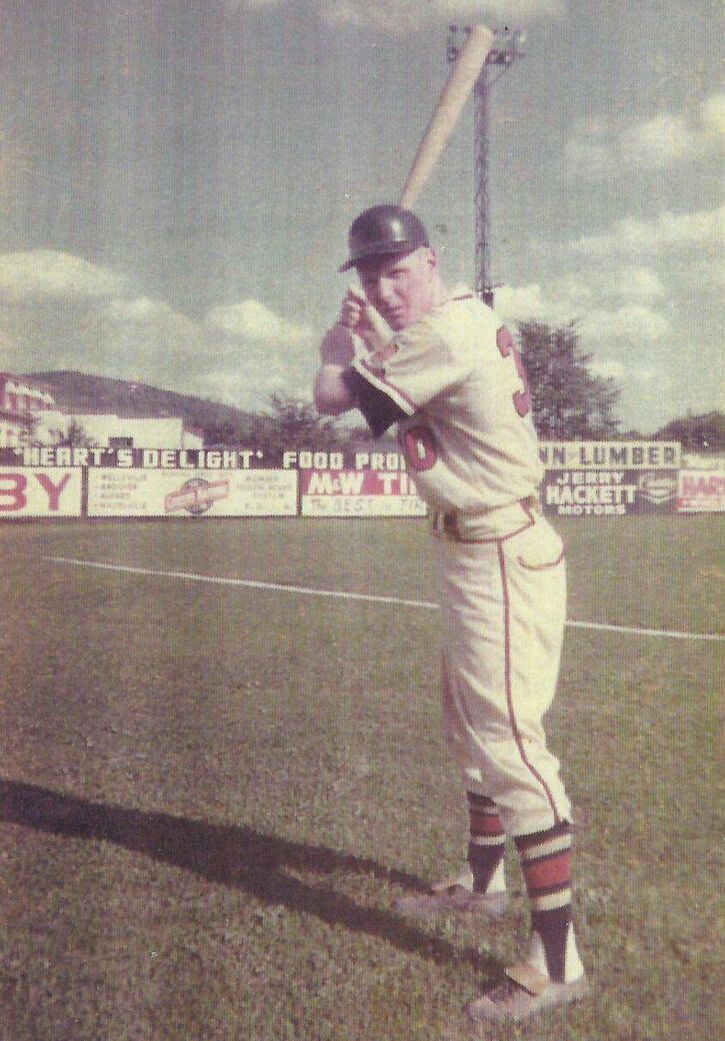

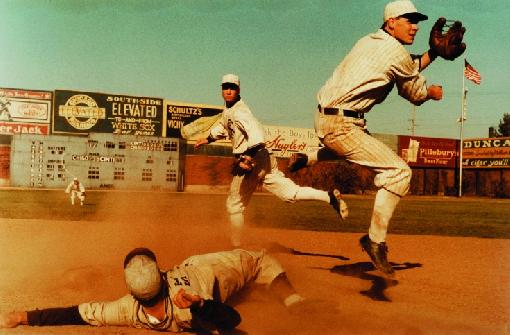

He was one of the most competitive athletes I ever covered – a fierce, purposeful flame. I wrote about Gibson (below) 26 months ago when he disclosed the fearsome diagnosis. I would also recommend today’s obit in the NYT by my friend Rich Goldstein: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/02/sports/baseball/bob-gibson-dies.html Also, you might want to see the piece I did in 2009 when Gibson and Reggie Jackson were promoting a book they had written (with Lonnie Wheeler) about the eternal struggle – that is, between pitchers and hitters. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/30/sports/baseball/30vecsey.html I watched the rivalry play out over a power breakfast in New York, and when I asked a question Gibson considered cheeky, he verbally buzzed me, high and inside. I thought Reggie was going to choke on his oatmeal, or whatever he was eating. His look said: “And you writers think I’m a hard guy.” I consider myself fortunate to have been around Gibson, in the tight little sanctums of the Cardinal clubhouse in the old, old ballpark. That kind of access to athletes is gone during the pandemic, with writers minimally getting sterile, mass interviews with a few principals, and I’m just guessing it never comes back. No writer today will see a star like Gibson, up close, the way I did in the tense last weeks of the 1964 season and World Series. Finally, a word about superstars. My admired colleague Dave Kindred has a mythical mind game called “The Game to Save Humanity,” meaning “we” get to play Martians, or whatever, one game, Pick your team. My pitchers are Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson, lefty and righty, even beyond numbers and longevity, but just, well, just because. I saw them. RIP, Hoot. It was an honor to observe you. From July, 2018: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/dont-mess-with-bob-gibson Don’t Mess With Bob Gibson Bob Gibson is fighting pancreatic cancer – “fighting” being the operative word. Everybody knows Gibson’s combative pose as the best right-handed pitcher in the universe, starting in 1964. I was lucky enough to be present when Gibson morphed from very good pitcher to legend, in 22 epic days at the end of that season. He had been underestimated by his first manager, Solly Hemus, who had lost his black players by using a racial taunt to taunt an opponent in 1960. Gibson was still very much a work in progress after Hemus was canned in 1961, and replaced by Johnny Keane, who reminded me of the kindly commanding officer, Col., Potter, in the classic series, “M*A*S*H.” After mid-season of 1964, Gibson pitched eight straight complete games – a statistic that probably would default the computers of today’s analytics gurus. Yes, really good pitchers really did finish a lot of games. As the Phillies started to fold, the Cardinals and Reds put on a run. On Sept. 24, Gibson lost a complete game in Pittsburgh. On Sept. 28, he beat the Phillies, going 8 innings. On Oct. 2, with the Cardinals in first place on the last Friday of the season, Gibson lost, 1-0, to the lowly Mets as Alvin Jackson pitched the game of his life. Then on a very nervous Oct. 4, Gibson pitched 4 innings in relief, gave up two runs, but was the winning pitcher, as the Cardinals won their first pennant since 1946. I can still see him on the stairs to the players-only loft. “Hoot, how’s your arm?” a reporter asked. “Horseshit!” Gibson said. Then he was gone, up the stairs. When Manager Keane gave his pennant-winning media conference, somebody asked why he went so often with a certifiably fatigued pitcher. “I had a commitment to his heart,” Keane said softly. Those words gave me a chill as Keane spoke them; they remain one of the great tributes I have ever heard from a manager of coach about a player. Keane’s faith, his shrewd understanding of the man, helped Gibson demolish the stereotype that many black players had to overcome. Gibson then started the second game (8 innings, lost to Jim Bouton), won the fifth game in 10 innings) and the seventh game in 9 innings to won the World Series. He had pitched 56 innings in 22 days, become a superstar after some delay, just as Sandy Koufax had done earlier. In over 70 years as fan and reporter, I will take the two of them over any lefty-righty pair you want to pick. Gibson never put away his testy edge. He was rough on rookies, rough on how own catchers and pitching who trudged out to the mound to counsel him. “You don’t know anything about pitching, except you can’t hit it,” he told Tim McCarver, who has relished that taunt ever since.) He did not observe the fraternity of ball players, even chatty types like Ron Fairly of the Dodgers. One time Fairly stroked a couple of hits off Gibson, who then hit a single of his own. But Fairly made the mistake of engaging Gibson in a collegial way. I always heard that Fairly praised Gibson for his base hit, but Gibson insisted that Fairly had raved about Gibson’s stuff and wondered how he had possibly made two hits off him. Either way, Gibson glared at Fairly. Didn’t say a word. Next time up, Fairly observed Gibson, glowing on the mound, and mused to the catcher, Joe Torre, that he did not think he was going to enjoy this at-bat, was he? Torre wasn’t going to lie about it; he just smiled as Fairly took one in the ribs. That is Gibson. Don’t mess with him. Torre later brought Gibson to the Mets as his “attitude coach,” as if you can coach attitude. Gibson remains competitive. A decade or so ago, he and Reggie Jackson collaborated on a nice book about the age-old yin/yang of pitcher/hitter. They met me for a power breakfast in New York to discuss their book, and it went fine until near the end. Working on a book on Stan Musial, I asked Gibson if I could ask one question about Stan the Man. “Absolutely not,” Gibson snapped. He and Musial had the same agent, and he knew that Musial had put out a fatwa against friends and family discussing him with writers. Gibson’s abruptness caused Reggie to nearly choke on his bagel as he tried not to laugh. Classic Gibson. This is the guy who is going to fight a formidable disease. Knock it on its ass, Hoot. * * * (Below: video of Christopher Russo interviewing Gibson (Reggie in background) about the friendly little incident with Fairly, back in the day.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wF1NCyYg0T8 https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/g/gibsobo01.shtml  Never heard of David Peterson or Andres Gimenez until they enlivened this "season" Never heard of David Peterson or Andres Gimenez until they enlivened this "season" With absolutely no regrets, I faced the end of the “regular” baseball season, not that anything has been regular about it. The Mets lost Saturday afternoon, and were eliminated, but I have no complaints. . Baseball has done well enough by me this summer. In a terrible time, baseball kept me reasonably sane, in a baseball-fan kind of way – that is, stomping upstairs at 10 PM, gritting the words, “It’s over. They stink.” The “season” came at just the right time – when I figured out we weren’t going to take a drive or visit our grown children or hug our grandkids or go out for dinner or return to the city, my home town, until this poor bungled country figured it out. For entertainment, for escapism, I would watch nearly 60 games’ worth of overmatched pitchers, erratic hitters, outfielders turning the wrong way on fly balls, base runners stumbling into outs, a catcher who couldn’t catch -- and that was only the Mets, the only team I follow. I don’t watch the Yankees (nothing personal, I’ve gotten over my tormented youth, plus Aaron Judge is one of my favorite players), and I cannot stand network baseball, with its overload of gimmicks and just-learned drivel and bland “experts.” I watch only the Mets, or listen to them, and it got me through two months. Besides, what were the alternatives? --Following the smokescreens of a crooked and deranged President? --Obsessing over a pandemic that remains unchecked in an inept "administration?" --Keeping up with merciless hurricanes and fires? I kept to the high road the first few months of the pandemic – reading good books, listening to classical music, watching National Theatre re-runs from London, keeping up with family and friends. But when baseball gave it a try in mid-summer, I devoted myself to the Mets my team since 1962 (even if I had to feign neutrality while covering baseball.) In a sick way, the Mets were fun this year, even as their pitching crumbled and Pete Alonso had a sophomore jinx for the ages.  Dominic Smith takes a knee Dominic Smith takes a knee As a fan, I enjoyed Jacob deGrom, the master, and somebody named David Peterson who finished with a 6-2 record Thursday night, as a rookie. I watched Jeff McNeil embarrass the analytics wizards who do not value a fiery throwback, a contact hitter who plays four positions. It was a joy to watch Andrés Giménez, 22, show speed and savvy and great hands whenever they would let him play. Time is on his side. It was also delightful to watch Dominic Smith blossom into a clutch hitter and get to use his glove at first base, and he learned to be a decent left fielder. But most of all, in a time of social awareness, as Blacks kept getting knocked off, Smith knelt to express his concerns, and wept with emotion.  Luis Rojas seems to have a grip Luis Rojas seems to have a grip . enjoyed watching the calm eyes above the mask of Luis Rojas, the accidental manager -- he's Felipe Alou’s son; that told me a lot. I tried to ignore the counter philosophy that said we should avoid this goofus version of a season – 60 games, a tie-breaker gimmick in extra innings, 7-inning games in doubleheaders, no pitchers hitting in the National League, and, worst of all, no fans. I heard baseball people say they are just beginning to appreciate the fans. Really? Just now? The other day, I read an article by Tim Kurkjian of ESPN, the writer-commentator who knows the sport, lamenting a baseball season without “fun.” Tim is terrific, but I want to say that in my masochist world, “fun” involves suffering. Fun? I was a Brooklyn Dodger fan in 1950 when Richie Ashburn threw out Cal Abrams at home, and in 1951 when Bobby Thomson hit the home run, and 1956 when Don Larsen no-hit the Dodgers. Was any of that fun? I missed it. The real “fun” of baseball is thinking along with the participants and the commentators. I know more about the game since I retired and have been able to watch and listen to Gary and Keith and Ron, plus Howie on the radio, even though this year they did not travel with the team but made their calls, as well as possible, off the TV in an empty Mets’ ballpark. Hard for them and the audience, but it was still a game. With the Mets not qualifying for the playoffs, I don’t plan to watch the long 16-team slog to a “World Series” but I might be a backslider I’m liable to catch the occasional soccer game in the winter months but I stopped watching football and basketball and hockey years ago. College football? I never had respect for the ugly alliance between colleges and football, and now the Pac-12 has joined the other major conferences in risking the health of the so-called students who will play during Trump's pandemic. I think voters will get rid of this vile and ignorant President, and maybe more Americans will wise up about how to slow down this pandemic even before a legitimate vaccine arrives. Speaking of change, prospective buyer Steve Cohen says he will bring back Sandy Alderson to run the Mets. This must mean Alderson's health is stable. But what does it mean for Brodie Van Wagenen, the agent who has been running the Mets the last two years? In the meantime, the Mets got me through a long hot summer, and that is something. *** Tim Kurkjian’s knowledgeable view of this weird season: https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/29898470/this-fun-how-everyone-baseball-navigated-very-different-season. When Lou Brock passed more than a week ago, my friend Jerry Rosenthal flashed back to a summer evening in St. Cloud, Minn, in 1961. Jerry was playing for the Eau Claire Braves, on a road trip to play the St. Cloud Rox, in the old Northern League. Jerry was a college guy, all-conference shortstop at Hofstra, where I was a student publicist. I saw him take a fastball over the left eye in 1959 but he willed himself back for two more seasons before signing with the Milwaukee Braves. Lou Brock was also a college guy, out of Southern University, academic scholarship, latecomer to baseball, and 1961 was his first season in the minors. “Lou was a great guy!,” Jerry recalled in an e-mail the other day. “Very personable and smart! I ran into Lou after a night game near our hotel in St. Cloud. He was reading ‘The Long Season’ by Jim Brosnan. Lou was surprised that an active major leaguer would write such a controversial book." Switched to second base in the Milwaukee Braves’ chain, Jerry got to see Brock up close in six games: “Not a big man, he was very muscular and had good power and blinding speed! Lou was at full speed on his second step, putting great pressure on infielders to getting rid of the ball as fast as possible! Needless to say, Brock turned singles into doubles and doubles into triples!” The next year, Jerry moved up to Yakima in the Class B Northwest League. He recalls how warm and welcoming that town was, how fans would recognize him and ask for his autograph. He treasures his memories of teammates like Rico Carty and Bill Robinson who had so much talent it was clear they were heading for the major leagues. He says that Robinson, my late-blooming friend, “had the best arm I ever saw from right field" -- how he stung Jerry's glove hand when Jerry was the cutoff man. Jerry also talks about his minor-league batting instructors, baseball lifers like Birdie Tebbetts, major-league catcher and manager, then a roving batting instructor at Wellsville. Tebbetts told him to go with the outside pitch to the opposite field -- and Jerry surprised himself with a game-winning home run to right, his second homer of the game. Jerry also met major-league stalwarts who loved talking Brooklyn Dodger baseball with him -- Dixie Walker, once The Peepul's Cherce in Brooklyn, and Andy Pafko, the old Cub who was standing at the wall as Bobby Thomson's legendary homer soared over his head. “In my rookie year at Eau Claire. I’m wearing uniform number 25, Bobby Thomson’s hand me down! How ironic is that? Pafko gave me his first-hand description of ‘the shot heard round the world’ and I was assigned to wear Bobby’s uniform! As a true-blue Dodgers fan, as a kid, that’s an occurrence that I could never have dreamt!” At Yakima, Jerry was steamrollered by one Spencer Scott at second base and was on the bench a day later. But Rico Carty, the regular catcher, was hurt, and the backup catcher was injured during a game, so Jerry hit for him -- and slugged a homer. Jerry had never caught in his life, but he caught that game, and another, until the Braves could send another catcher. The players were always competing against others in the Braves system. A brash kid from Missouri, Ron Hunt, informed Jerry in spring training that, as a former shortstop, Jerry did not know squat about the double play from second base, and Hunt, who loves the game as much as Jerry does, demonstrated the proper pivot steps -- then moved past Jerry in the chain. By 1963, Hunt hustled himself into a regular job with the Mets, and a great career. By then, Jerry was out of baseball, teaching school, playing semi-pro ball and taking care of his Irish mom. However, he kept up with his old minor-league colleagues. In Shea Stadium, he said hello to Bobby Cox, who had played against him in the Northwest League and was now a successful manager with the Braves. Cox warmly greeted him and recalled the entire Yakima infield, including "Rosey." Jerry never ran into Lou Brock until he went to a baseball dinner in New York many years later. In a crowd, he greeted Brock, who said he remembered him from the Northern League, but other people interrupted and they never got to chat. Still, there is a bond between players who “made it” and those who did not: they all played the game. The backdrop is the minor leagues – the cruel classroom where a difficult sport is taught, where most dreams were destroyed. Jerry, in retirement, lives in the city, is close to his sisters and many friends, catches good movies and knows restaurants all over town, reads a lot, and has traveled all over the world, usually by himself. He played in a senior hardball league, finally getting his Spencer Scott knee replaced. As a fan, Jerry adopted Jeff McNeil, the scrappy Everyman late bloomer who had fought to become a .300 hitter the Mets never expected. Jerry is barely following this weird “season.” He has a raging contempt for the short-sighted proprietors of baseball and their still unproven commissioner, Rob Manfred, who are scheming to devour a number of minor leagues to save a few dollars. That rash move would be an insult to the history, the soul, of the sport -- fans who used to say they saw a rag-armed lefty named Musial pitching in the low minors, or fans in Trenton could say they saw a comet named Mays heading straight for the 1951 World Series. That hallowed system allows old minor-leaguers like Jerry Rosenthal to display ancient box scores and mourn stars like Lou Brock, and sometimes able to say, with all due respect, "Back in 1961, I out-hit Lou in our six games." * * * COMMENTS PREFERRED ON THIS SITE RATHER THAN MY EMAILS--THANKS, GV COMMENT FROM JERRY: George, here are my comments regarding your fine piece. George, it was an honor being the subject of your great piece, “My Friend Out Hit Lou Brock....in Six Games.” I will always treasure my minor league memories ; the highlights as well as the lowlights. Your superb writing brought out how important the institution of minor league baseball is to the development of young prospects and to the small towns they play in! For over one-hundred years, the minor leagues and major leagues have had a mutually beneficial relationship. Sadly, that relationship no longer exists! MLB ‘s arbitrary decision to “contract” 42 minor league, owner-operated, clubs could be the “beginning of the end “of the minor leagues! Clearly, the commissioner and the thirty MLB owners are only interested in increasing revenue, not preserving the traditions of the game! George, you were right on target when you described the minor leagues as -“ the cruel classroom where a difficult sport is taught, where most dreams were destroyed.” I played for three great managers: Jim Fanning, Bill Steinecke and Buddy Hicks. These “baseball lifers” taught me facets of the game that I was completely unaware of coming out of college! Just as important, these fine men told us to view “self-doubt” and “failure” as just part of the game! They all emphasized the idea that mental toughness was as important as physical skill! My managers were very aware of how you dealt with adversity! We didn’t know it at the time, but we were being taught “ valuable “life lessons”! I will never forget their words of support and encouragement! These are just the kind of mentors organized baseball needs today! I’m sure MLB’s response to that idea would be: “We are going in a different direction”! George, thanks again for this wonderful piece! Thanks for being a good friend for these many years! Jerry Rosenthal * * * https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=rosent001ger https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=brock-001lou The city shimmers in the night sky.

I take my walk after the sun goes down, and sometimes a magnetic force pulls me to the crest of a hill facing west. My home town is out there, but at the moment I cannot construct any excuse to visit, much as I miss it, blessed to live in a lovely close suburb, as far from the city as I can stand. Sometimes I think of the great walks I have taken in recent years. Last winter, just before the plague struck leaderless America, I took the A train, thinking of Billy Strayhorn's immortal song, saxophones racing uptown, and got off at 125th St. and strolled east to Third Ave. and then south to 80th St. for my monthly lunch with some baseball/writer pals. Every block was an adventure, now a distant memory of a lost city, Atlantis on the Hudson. * * * How is New York? Fortunately, The New York Times had one of its very best writers, Dan Barry, write the text for a section of photos by the equally artistic Todd Heisler, in Saturday's paper, also available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/20/nyregion/nyc-sights-sounds-coronavirus.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage&contentCollection=AtHome&package_index=0 * * * Their artwork in the NYT makes me miss New York even more. Some losses are irreparable, including the fabled Irish baseball pub, Foley's, run by Shaun Clancy. When the plague hit, Shaun realized he could not recover the losses in the foreseeable future, so he put his memorabilia in a warehouse, and retreated to his home in Queens, my home borough. As it happens, his home is -- that is to say, was -- exactly two miles north of my family home, both on 188th St -- his in Auburndale, mine in Holliswood. Last week, as Shaun sold his house, we finally arranged our long-discussed socially-distanced meeting. I picked Cunningham Park, the park of my childhood, where my family had corn-and-hot-dog picnics and I played sandlot baseball and kept an eye out for a girl who lived a few doors from the park. For our long-delayed meeting, Shaun and his companion, Kristie Ackert, baseball writer for the Daily News, and I sat at a picnic table in the shade and drank iced coffees and talked about Ireland and Queens and how Kristie covers the Yankees without access to the players. I told Shaun again how much Foley's has meant to my jock pals from Hofstra who are mourning our decade of occasional lunches at the back table. He's got a place in Florida, and Kristie will be there a lot when she is not watching the Yankees in empty ballparks. I miss my friends...and I miss Foley's...and I miss the magic place that glitters off to the west on a summer evening. * * * I see your silver shining town But I know I can't go there Your streets run deep with poisoned wine Your doorways crawl with fear* *The Pride of Cucamonga, Philip Lesh and Robert Peterson. Sung by Lesh with the Grateful Dead. This is how bad it got bad at the Mets’ home opener on Friday:

When Edwin Diaz walked into the game, the cardboard mockups of real fans began to head for the exits. I swear. Edwin Diaz! Aaagh! Not him again! Cardboard people began checking with the baby-sitter on their phones, began edging toward the rest rooms, began filing out toward the parking lots and the No. 7 elevated train – to get the hell out of there before Diaz torched the place, again. Eight innings into the first game of this bizarre season -- a season I am not sure should exist, given the pandemic -- I experienced the mini-terror of the fan – with no ticking clock, with three massive last outs to achieve. This is the same Edwin Diaz who was acquired by the Mets last year and had one of the worst years ever for a so-called relief pitcher. Fans groaned when they saw him flexing in the bullpen. On Friday, as rigid and lifeless as the fans appeared, they knew a terrifying situation when they saw it. It was a classic Mets’ game of recent seasons, Before Covid. Jacob deGrom pitched five crisp innings, looking like the two-time Cy Young Award winner that he is, reaching his pitch limit, and turning the game over to the bullpen. All those vividly-colored one-inch-thick fans recognized the script – the paralysis of the Mets’ hitters whenever DeGrom pitches. This opener had a subplot – the presence of Freddie Freeman for the Braves, after a terrifying siege with Covid months ago, when he admittedly felt he would not live. Later, he recounted his experience to Nick Markakis, a teammate, who promptly decided to sit out this season. Freeman is back, one of those admirable opponents that even some Mets fans, in all their bilious loyalty, can respect. He monitored first base, and seemed to greet the Mets’ Brandon Nimmo with a tap of his glove after both of Nimmo’s singles. This camaraderie would not have gone over back in the day, when an opponent would have fallen to the ground and called for the umpire to eject Freeman for menacing with his microbe-laden glove. In these nicer times, it was good to see Freeman’s hawk-like features back on the field. The Mets got a post-deGrom run when Yoenis Céspedes clubbed a massive home run, and Diaz induced terror in Mets fans by striding onto the field, but somehow he procured three outs, around a walk (to Freeman), to secure a 1-0 victory, and the Mets remained undefeated 24 days into July. This patchwork “season” may or may not last 60 games. But on Opening Day, with thousands of faux fans planted in the seats, a pyromaniac “relief” pitcher terrified the fans, in whatever form. I know it is hypocritical of me to worry about spreading the virus -- (the Mets abandoned all pretense of safety when they greeted Cespedes in the dugout)-- but baseball, in this strange form, is back. Cardboard spectators stared vapidly from behind home plate, their expressions never changing as the Mets and Yankees committed something akin to baseball.

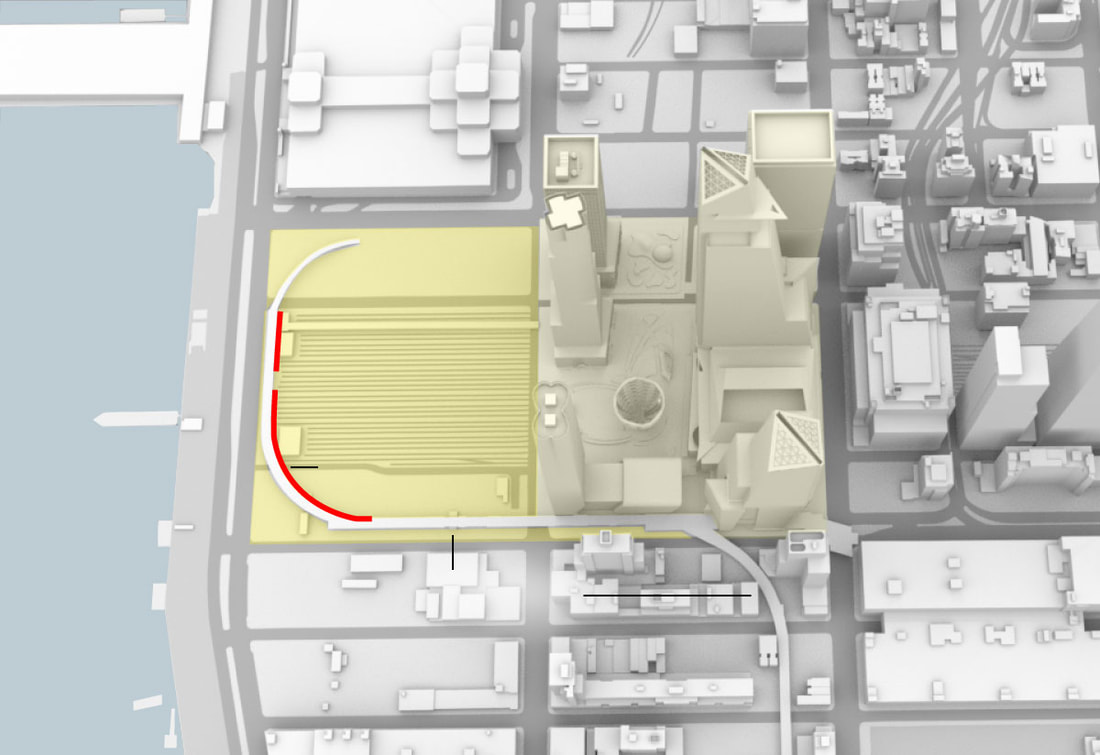

This was the ambiance at New Shea Saturday night as Major League Baseball introduced Covid-Ball, a makeshift version of the great American pastime, or what used to be. Cruel boss that I am, I assigned myself to stick it out as a preview, or warning, of what this truncated season will be, if it lasts its threatened 60 games. (Some wary big names have already dropped out for this season; others are trying to come back from a Covid attack. To be continued.) This was only an exhibition, spring training in mid-July, and there was to be another one at Yankee Stadium Sunday evening before the “season” opens late in the week. I will tell you up front that my biggest thrill of the night was seeing the aerial view of Queens, my home borough – the globe in the park, a glimpse of the wonderful Queens Museum, the No. 7 elevated train gliding through the neighborhood, as sweet as a gondola through Venice. Oh, my! I am so homesick for Queens! I thought of the joys within a mile or two of this sweet spot – my friends and the heroes at Mama’s deli on 104th St., other friends at the New York Times plant, just to the east, the food and the crowds in downtown Flushing, the Indian food in Jackson Heights, and so on. I miss all these at least as much as baseball. There was a strange hybrid form of baseball taking place in New Shea. Yankee manager Aaron Boone was moving his jaws inside his soft gray mask, either chewing something or talking a lot. The first home-plate ump (they mysteriously rotated during the game) had some kind of plexiglass shield inside his mask, to ward off virulent Trumpian microbes. I was mostly watching the Mets’ broadcast, with good old Ron and good old Keith two yards apart in one booth and good old Gary in a separate booth, but their familiarity and friendship came through. Welcome to this strange new world. Later I switched to the Yankee broadcast and realized Michael Kay and the others were not in Queens but were commenting off the same video we were seeing. Not sure how that will work out during the season. Early in the game I learned that the Toronto Blue Jays will not be able to play in that lovely city this “season,” for fear of being contaminated by the virus the viciously bumbling Trump “government” and block-headed Sunbelt Republican governors have allowed to rage. I don’t blame the more enlightened Canadian government – but a few days before the season opener? The Jays will apparently play in Buffalo, creating all kinds of logistical horrors for anybody in Ontario with Blue Jay business. The highlight of Saturday’s exhibition was Clint Frazier, the strong-minded Yankee outfielder who plans to wear a kerchief-type mask during games, including at bat. Does a mask impede a batter’s reaction to a fastball, up and in? Maybe. But Frazier unloaded a 450-foot homer into the empty upper deck – (Sound of summer: Michael Kay: “SEE-ya!”) -- and some teammates in the dugout flashed masks in tribute to Frazier. I obsessed about those cardboard fans behind home plate. The absence of real people takes away one of the peripheral joys of watching a game – demonstrative or even annoying fans, the occasional celebrity, and, yes, I admit, women in summer garb. Will these faux fans become part of lore? Will they be rotated, replaced by new faces during the “season?” Just asking. Finally, there was the recorded crowd noise, an apparently steady hum. No pro-Met chants, no anti-Yankee jibes, just background, like the roar of the sea, I caught the last inning on the Mets’ radio broadcast, where good old Howie was speculating that the home-team genies in the control room were raising the sound a bit when the Mets were rallying. I stuck it out because I had assigned myself to “cover” the event. But I wondered about the reaction of my pal, Jerry Rosenthal, one-time all-conference shortstop at Hofstra, two-year Milwaukee Brave farmhand, and now lifetime baseball purist and authority. How did Jerry like the ersatz game? He texted: “Watched one inning of the game. I am now watching ‘The Maltese Falcon” for about the 25th time. That should tell you something!” Yes, it does. Play “ball.” I love baseball schedules --get all excited when they come out, months ahead. Look for big rivalry series, the odd day game, illogical road trips. Force of habit, from being an old baseball writer.

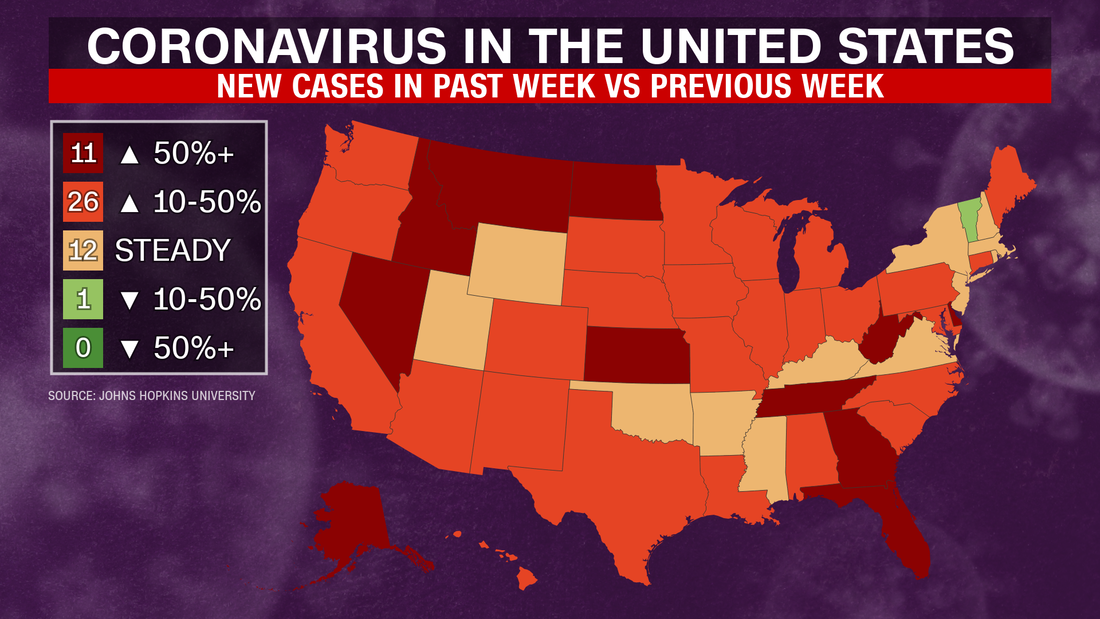

Lately, I've been fascinated by pandemic charts, like the current one above. The makeshift 60-game baseball schedule also caught my attention, sucker that I am. I could visualize Jacob DeGrom keeping the batters off balance, Jeff McNeil smacking the first pitch of the season for a base hit. But now, I realize I was wasting my time. This 60-game improv season may start, but it won’t finish. This realization has been dawning on me for days, beginning when Ryan Zimmerman of the Nationals said he was going to sit this one out, and growing when Mike Trout and others said they just weren’t comfortable going out to play ball in the time of the virus, when they had responsibilities to wives, to children, to family members. Ball players, collectively, are clearly smarter than the governors of Texas, Arizona, Georgia and Florida, who followed the lead of the ignorant man in the White House, and decided to get back to business without a clue about the pandemic. Where do they get these people? Now the infection is reaching the young louts who jumped up and down and exhaled on each other in close quarters at beaches and pools and bars in recent months, with no masks, just to prove a government could not tell them what to do. Now, the cobbled-together “protocols” for players and staff members are coming undone. Players – and their colleagues in the other team sports – were supposed to live hermit lives when not socially-distancing at the stadium. Only they know if they did, and maybe it makes no difference. I saw soccer players in England hugging each other after goals on Saturday. Boys, boys, boys. Even before the games start, baseball players have picked up microbes floating on the breeze in the clubhouse or the hotel lobby or the team bus or whatever. It was never going to work, not while this nation, relying on a fool who has sabotaged the federal government, was falling further behind the murderous path of the virus. On Saturday, the Yankees announced that Aroldis Chapman, their ace relief pitcher, had come down with the virus. He joins two other Yankees expected to be vital in this theoretical mini-pennant race. May all the cases be mild. But the number has reached critical mass. The players want to play, and the owners want to make money, and sucker fans like me want to watch games from empty stadiums. (It works pretty well with watching top-level soccer, I’m here to report.) However, Europe appears to be more disciplined than our poor run-amuck country, forsaking science for the ravings of the Pied Piper of Mar-a-Lago. This experimental season may start in less than two weeks. I miss baseball and I will watch the Mets when I can. However, 60 games are going to seem an eternity when more healthy young athletes come down with this virus. Under the “leadership” of Rob Manfred, baseball is going to stick it to the players in labor negotiations next year. So even if somebody outside this government comes up with a vaccine and some leadership, baseball's traditional "wait til next year" is a long, long way off. * * * Current list of ball players who have already chosen to miss 2020: BC: Before Chapman. https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/29386803/mlb-players-opting-2020-season Saturday's virus scorecard, including Aroldis Chapman: https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/07/11/sports/baseball/ap-bbo-baseball-rdp.html?searchResultPosition=2 I’m getting the feeling that baseball is negotiating itself out of even an abbreviated season.

And maybe that’s okay. I’m not sure anybody should be doing something as unimportant as playing sports, what with the murderous virus still very much floating in the air we breathe. Then again, I truly miss baseball. I can’t watch old games on the tube, just can’t, but I can read about them. I just read a book about my favorite team from somebody who was “in the room where it happened.” (From “Hamilton”) That would be Jay Horwitz, owner of the largest head this side of Mr. Met, the mascot for whom he is often mistaken. The book is entitled “Mr, Met: How a Sports-Mad Kid from Jersey Became Like Family to Generations of Big Leaguers," issued by Triumph Books. Horwitz was the head public relations person for the Mets from the time of Joe Torre through the time of Terry Collins (both of whom he openly admires.) As Jay tells it, confident managers like Davey Johnson relied on Jay's ability to keep a secret, and explained personnel moves or strategy decisions, counting on him to put a positive spin on them. The book is full of examples of Horwitz offering advice to players, particularly the younger ones, moments after a game, before the vicious bloodhounds of the media came yowling through the clubhouse door. Let me attest that Jay Horwitz has not yet in his life given any journalist (or at least me) a truly newsy “scoop.” He made his rep as a college PR man who could get Fairleigh Dickinson in the sports pages, in the waning days when print dominated sports coverage, and he was not about to divulge anything damaging or derogatory about any Met that ever lived. Therefore, he had the run of the place. For example: Horwitz was in the locker room on the night of Oct. 25, 1986, when the Mets and Red Sox played the sixth game of the World Series. When the game went into extra innings, he knew he had to get to the Mets’ clubhouse to console or congratulate the players but also to monitor the post-game madness. He was sitting in Davey Johnson’s office with Darrell Johnson, one of the Mets’ advance scouts, watching on TV as the Red Sox scored twice. Then Wally Backman flied to left and Keith Hernandez flied to center. (Anybody who was there will never forget the Shea Stadium scoreboard prematurely flashing congratulations to the Red Sox.) A minute later, Hernandez burst into the clubhouse, not about to gawk like some tourist as the visitors celebrated in the Mets’ house. Then the three of them watched Gary Carter, Kevin Mitchell and Ray Knight single to bring the Mets within a run “I’m not leaving my chair,” Hernandez declared. “It’s got hits in it. It’s a hit chair.” Most ball players believe that stuff. Then Mookie Wilson had perhaps the greatest at-bat in the history of the Mets and as the Mets roared in from the field, Jay Horwitz “was in the room." In bad times -- and for the Mets, that's most of the time -- Horwitz suffered and sighed so visibly the players treated him as one of them, including when they divided up the World Series swag. This is the annual autumnal test of character, with some teams generous to people who serve them, and some teams not so much. The club was passing out $4,000 bonuses to department heads but the players voted Jay in for a full share -- $93,000 -- the same amount as Hernandez and Carter and Mookie, a highly unusual gesture. He was hesitant to break tradition, but says players like Mookie insisted he take it. Then Jay consulted the person who truly had his back – his mother, Gertrude. “I didn’t raise a schmuck,” she told her son. “Take the 93.” The share was a big payoff for Jay Horwitz but it sounds as if he had a payoff every day he reported to work -- a loyal PR man, as unathletic as they get, who has gone through life with only one eye working due to glaucoma at birth. A bachelor, he has put his loyalty into the Mets since 1980, and the players (often the stars like Tom Seaver or John Franco) often showed their love by dousing him from the whirlpool hose, cutting his tie, slipping greasy foodstuffs in his jacket pocket as he slept on the team airplane. Jay still seems to beat himself up that he did not do enough to steer young Doc Gooden and young Darryl Strawberry, who found ways to self-destruct early and often. He does not go into details, but he trusts the reader to know them. After the 2018 season, the Mets’ new front office created a new job as vice president of alumni relations; Jay now brings back old Mets, some immortal, some transient, for some feel-good events, plus he still gets to report to the ballpark every day. In the absence of baseball, this sweet book shows the beating heart of a sport that normally takes place every day. Jay Horwitz and loyal fans (I outed myself as a Mets fan after retirement) may have a long wait to root and suffer during a game, any game. The Horwitz book gives a glimpse of the daily agony, unique to baseball. Big-time sports returned to the tube -- and to empty stadiums -- on Saturday, with the Bundesliga returning first. Two squads -- and four socially-distanced ball persons in the four corners of the yawning stadium -- celebrated, at discreet distance. But was it worth the cost, real or potential? Many of us have been mulling this over since various major leagues have tried to figure out whether to tempt the fates, and Covid-19, by providing "bread and circuses," as one reader asked recently, citing Cicero. Just watching the normally-emotional Ruhr regional Revierderby from the safety of my living room, I could appreciate the skill of the players after a two-month layoff. But what was risked, in Germany itself or around the world? Do we need this circus when people around the world are struggling to produce....and find....the bread part? The game itself was fine. Dortmund beat FC Schalke 04, by a 4-0 score, and let us see Erling Haaland, the 19-year-old prodigy from Norway. But how many sacrifices, how many tests and masks and medical attention were spent, just to produce this spectacle? Germany may not even be the best example for the risks because, as Rory Smith pointed out in his Saturday soccer column in the NYT, Germany already has a good record in lowering the damage from the virus, plus it already has a good national health program. Germany is also blessed with Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has "the mind of a scientist and the heart of a pastor's daughter," in the words of one observer. What happens if the U.S. and Canada start playing baseball again, or hockey, or basketball or soccer? What could go wrong? I had a revelation on Friday when I joined a Zoom link of baseball/writer pals who normally have lunch once a month. A few were hopeful about a start of the baseball season, but other buffs, who can cite arcane stats from half a century ago, seemed willing to let this year slide past without baseball, so that a few more tests could be available to a giant and deprived nation. We all miss the games, but we have bigger questions. I'm not going near my barber, or doctors, or even the hardware store, until I think it won't jeopardize my wife and me. I was happy on Tuesday when some of the parks opened near me on Long Island, but only to "passive" exercise. On my way back toward my car, I spotted a miniature ball field, with artificial turf, and I stood at home plate, in the left-handed batter’s box, and pretended I was Jeff McNeil, the old-timey cult figure with the Mets. McNeil flicked his bat, smacked a single into left-center field, and I felt immense joy that this might happen sometime again soon. Then reality struck me. Should kids actually use this field this season? On Saturday, we saw German players making contact on a corner kick or running into each other "by accident.?" , Assuming labor and management can agree how to share the TV income from games in empty baseball stadiums, we might observe the players, coaches, managers and umpires all violating each other’s breathing space?  Social distancing -- until crowds arrive. Social distancing -- until crowds arrive. Given the murderous intruder, does any of this collective behavior make sense? The world is also suffering an economic crisis, cited by the disturbed man in the White House, unable to take in information from experts. Sports seem to fall into the category of "opening up" the economy. Now we have thuggish Trumpites, back up his rantings. Carry the economic "opening up" to people playing sports for our entertainment. I would hate to think the ball players are posturing about safety for a better slice of the TV pie. It's their lives at stake. The players want to play, but their concerns are obvious from the Twitter stream by Sean Doolittle, the Washington Nationals’ closer and one of the more thoughtful heads in the game. https://twitter.com/whatwouldDOOdo/status/1259920490992410626 And what about the health of clubbies who pick up damp towels the players deposit on the floor (never, ever, in the basket)? What about the physios who knead aching backs or hamstrings for hours at end? Is any of this risk worth it so players can play, and owners can take their half out of the middle? Here, I am guilty of gross hypocrisy: If they build it, I will watch -- in the safety of my den, messaging with my son in his own lair. I enjoyed watching the Bundesliga Saturday and the Fox broadcasters tried to explain the Revierderby in this vital region of Germany -- hard to tell from an empty stadium. Americans did get to see Weston McKennie start for Schalke. He's had better days, but his was better than the day of Gio Reyna of Dortmund, who hurt himself in warmups and did not play. Those were fan sub-plots. For the players and support people in empty stadiums in Germany on Saturday, these are life-gambling decisions. I hope they know what they are doing. Your thoughts? Comments welcome. Oh, my goodness, it was 20 years ago.