|

I just read a powerful book about the first class of women at Yale University – in the fall semester of 1969.

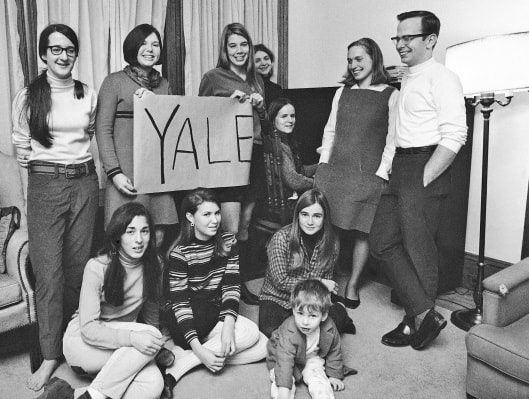

Yale, bless its crusty old heart, managed to enroll female students who were more than up to the academics of the great university, but also quite able to speak up – and act up -- for their rights. It was the 60’s, after all. That tumultuous year of 1969 is the backdrop for the book, “Yale Needs Women: How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant,” by Anne Gardiner Perkins, who arrived at Yale eight years after the first female undergraduates. After years of pressure, Yale finally joined many all-male schools that had accepted women, however imperfectly. Given the limit of 230 spots for women (along with the usual 1,000 spots for male freshmen, all regarded as “leaders”) the admissions department did a fine job, finding women with talent and guts to go along with the brains. Many pioneers depicted in the book do not come off as stereotypical silver-spoon, prep-school graduates but rather the best and brightest from all over – rock stars in their way, with the spirit of Tina Turner and Grace Slick and other icons. In Perkins’ book, these women are as diverse as any admissions director would dream: Among my favorites are Connie Royster, boarding-school grad, actor, African-American, worldly, teaching her instant good friend, Betty Spahn, white, from the Midwest, how to handle chopsticks; Kit McClure, from a New Jersey suburb, talking her way into playing her trombone on the all-male marching band, later cutting much of her red hair and helping form a rock band with a powerful feminist soul. Another pioneer was Lawrie Mifflin, who forced Yale to start a field hockey team – with real uniforms! with a real field! With a real coach! Lawrie became a journalist after shaming the all-male Yale Daily News into covering female sports. She later became a deputy sports editor at the Times -- and a good friend of mine -- and is today the managing editor of “The Hechinger Report” and was recently honored by Yale for her many accomplishments. Not all the women were activists at heart, but most were pushed into action by conditions: no locks in the bathrooms, not enough security at the dorms or around the campus, hardly any female teachers or administrators, and the feeling of being patronized in the classroom while also being hustled for dates (and more) by male students -- and male teachers. (The university still bussed in women from all-female schools, a long tradition.) Fortunately, the women had a champion in Elga Wasserman, with a doctorate in chemistry, who was appointed a sort of dean of women – but without the title, without the power. Wasserman fought for the women, minute by minute, but was eventually seen as a problem by the patrician president, Kingman Brewster, Jr. Two other heroes were a couple, Philip and Lorna Sarrel, he a gynecologist, she a pediatric social worker, who worked as a team to offer medical services and counseling, so much in demand that their one lecture class on sexuality was attended by over 1,000 students – women and men. Facing difficulties they probably could not have imagined, the women demonstrated, infiltrating clubby bastions, making the establishment aware of how things worked, and did not work. There was pain, including at least two rapes of women in the freshman class. Within the four years of their entry, the women had lobbied for more spots, challenging the quota of 1,000 male “leaders” who were accepted annually. Eventually, they achieved gender-free admissions, to the point of numerical equality today. Yale, being Yale, could attract these women -- and diverse men -- of excellence. On campus during the first four years of the pioneers were such future leaders as Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Janet L. Yellen, Kurt L. Schmoke and – sound the trumpets! -- from my old school, Jamaica High in Queens – Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, in her 13th term, now from Houston. Perkins has written a gripping guide on how to seek change in today’s world – as young people realize that our “leaders” are “leading” the U.S. in an assault on democracy and law, prejudices are seeping back, and young people face a future on a smoldering planet. The women of 1969 are admirable role models for all. * * * I mentioned the Yale book to my kid brother, Christopher Vecsey, a professor at Colgate University, which went coed a year after Yale did. Chris (he never tells me anything!) said Colgate held a symposium last April: “Women and Religion, Philosophy and Feminism,” featuring pioneers of 1970. Chris is also the editor of a book from the symposium: https://www.colgate.edu/news/stories/symposium-honors-professors-wanda-warren-berry-and-marilyn-thie * * * NYT review: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/13/books/review/yale-needs-women-anne-gardiner-perkins.html?searchResultPosition=1#commentsContainer NYT retrospective this fall: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/upshot/yale-first-women-discrimination.html

Josh Rubin

12/17/2019 04:42:37 pm

Interesting story. Of course, 1969 seems awfully late to me. My alma mater (Oberlin) was racially integrated in 1835 and co-educational in 1837, first in the US to do either.

George

12/17/2019 09:30:53 pm

Josh, I did not know about Oberlin's "firsts" but I did know it is way up there in colleges and among Ohio's many fine schools. When I was covering Appalachia, Oberlin students were all over, doing research and outreach.As I recall, they were very active in the epic election in the United Mine Workers' Union, which sent Arnold Ray Miller to DC. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|