|

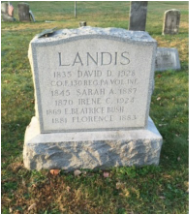

Taking a walk on a back road, I spotted a country graveyard full of names, German, Dutch and English, many from the early Nineteenth Century: Mohler. Miller. Fortney. Studebaker and Stewdebaker, side by side. First names like Isaac and Levi and Israel. One family lost two little boys, born in April, died in summer, three years apart. Some of the weathered gravestones list the men’s units in the Civil War, but all the men I noticed came home, some living into the next century. Whatever they saw or did, they were the lucky ones, consider- ing what happened 20-plus miles south. A few miles north of the church is Camp Hill, where in 1863 a small detachment of Confederates made an exploratory mission toward Harrisburg, Robert E. Lee’s goal. The invaders skirmished with Union soldiers but Albert Gallatin Jenkins’ troops were called south because an impromptu battle was shaping up in Gettysburg, 35 miles away. Camp Hill, where part of my family now lives, would be the farthest penetration north by the Confederates, (See the excellent article on PennLive in 2013.) In that portentous late June of 1863, a boy named W.O. Wolfe was standing by the Gettysburg road when Fitzhugh Lee’s soldiers headed south. Many years later he would tell his own young son how he gave surly replies to the Rebel officer, who menaced him, perhaps for effect. Some of those troops who passed the Wolfe farm were from the hills of western North Carolina. By the strangest circumstance, the boy grew up to be a stonecutter, and settled in Asheville, North Carolina, and married into a clan of southern hill people. To his dying day, W.O. Wolfe would curse his luck, would speak longingly of the lush farms of Pennsylvania Dutch country. W.O. Wolfe was a storyteller; who knows how much he embellished the tale of the meeting the Rebels on Gettysburg Road, summer of '63. He even put an in-law into his story: an officer who preached the Bible while riding toward Gettysburg, and who smelled so bad that his own troops referred to him as “Stinking Jesus.” W.O.’s late-in-life son was also a storyteller. Thomas Wolfe incorporated his father’s tales into the opening pages of his first novel “Look Homeward Angel.” Later he expanded it in “O Lost,” which I once read in the Wolfe library in Chapel Hill. Thomas Wolfe is my most beloved writer; he informs my ongoing adolescence. Perhaps some of the people in the country cemetery near Camp Hill also saw Rebel soldiers as they rode or walked south, toward Gettysburg. We stayed in a comfortable Marriott Courtyard, made coffee in our room. Child hockey players were congregating for a holiday tournament. * * * Footnote 1: I just learned from a terrific web site by Steven B. Rogers that there is a Wolfe Diner in Dillsburg on Route 15. But now I’m home. Footnote 2: My wife reminds me that in Dillsburg there is a nice restaurant, Pakha’s Thai house, which we have visited several times. The web site says: “The most authentic Thai meals this side of Bangkok.” Footnote 3: James Taylor, son of North Carolina, long moved north, wrote a lovely tribute to Confederate soldiers, limping home from war. 11/28/2015 12:10:26 pm

Thanks for sharing you website with me. I have written and lectured extensively on Thomas Wolfe, including his ancestors in and around York Springs, PA. And thanks for the shout out for my own blog. Always nice to know its being seen and read.

Brian Savin

11/29/2015 10:24:30 am

The Wolfe reference turned on a light for me. I looked up whether the "other" Tom Wolfe was related to yours. They are not, but that other Wolfe made "literary journalism" a popular concept, and it occurred to me that is actually the hallmark of GV journalism and why it is so appealing. This post, for example, is, to my own reading, structured by scenes that move the story along. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|