|

One of the more sordid scams in the history of book publishing began 50 years ago – and I had a modest part of it.

A bunch of us from Newsday collaborated on a tale of sex in the suburbs, titled “Naked Came the Stranger.” Some people bought it and read it and thought it was not so bad. The legend does not die. The radio landmark, Studio 360, is recalling this assault on the reading habits of the American public in a podcast released Thursday evening: http://www.wnyc.org/shows/studio/segments The show was supposed to have been heard Thursday evening on WNYC-FM (93.9) in New York but apparently there was other news, and it was broadcast on Saturday. It was fun to hear the able producer Sam Kim recreate the foolishness that began with a late-night conversation at a bar frequented by journalists, cops and criminals and other people who stay up late. (I was not there.) From that conversation, Mike McGrady, a columnist, and Harvey Aronson, feature writer and wily manager of the Nightside softball team, decided to collaborate on a book about a woman looking for revenge on her philandering husband, by seducing every male in her Long Island suburb. McGrady and Aronson set up some basic ground rules – mainly, descriptions of the main character's hair and figure – and invited people to contribute individual chapters of their fetishes and fantasies. I found a request in my mailbox and assumed I was one of the chosen few. (Later I discovered McGrady and Aronson had stuck a copy in just about every mailbox at the office.) They say writers should stick to what they know. I was (and remain) a rather boring husband and father with no personal knowledge of the “cheatin’ side o’ town,” as the country songs say. So I wrote about a schlubby suburbanite and his lovely wife, busy renovating their old house. While tending to his lawn, he gets seduced. Having taken typing in junior high school, I finished my chapter in half an hour. I wrote as artfully as I possibly could and turned it in. Weeks later, McGrady and Aronson told me my level of writing was exactly what they wanted. At the time, I thought it was a compliment. Let me say a word about the Newsday of the mid-60’s, how it quivered with energetic young people, many recruited from the city. I still consider that Newsday as “we,” the way ball players talk lovingly about their first club, where they learned to play the game. By 1969, I had moved on to the Times, as the book, doctored up (or down) by McGrady and Aronson, was emitted, under the name of Penelope Ashe, actually somebody McGrady knew. We kept the secret as long as we could, while the hoax soared toward third on the best-seller list. A few reviewers even found literary merit – a piercing look at modern suburbia. Sam Kim has tracked down some of my old pals who are still around to tell the tale, including Aronson, but Mike McGrady, so talented, has long since passed. These two fine people had the idea and did most of the work, yet they shared the not-inconsiderable royalties equally among 25 people who contributed something. I rate this as one of the most generous acts in the cut-throat history of publishing. Not everybody was charmed. A librarian in my town, Mrs Murray, would sigh and roll her eyes whenever she spotted me lurking in the book shelves. A few years later, a movie was published under the same name but without the high literary quality of our book. My mentor, the whimsical sports columnist, Stan Isaacs, rented a hansom carriage to take us in style to the porn theatre. I make no apologies for defiling the high standards of publishing. Mike and Harvey helped put our kids through college. I still mow my own lawn. Who thinks about Casey Stengel these days?

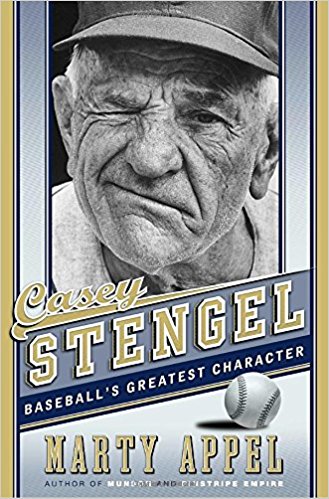

Mets fans should, because he basically invented the Amazin's. Just the other day, a hit rolled into the right-field bullpen and a Braves outfielder flung aside a garbage pail to retrieve the ball -- a garbage pail! -- and I recalled what the Old Man used to say: "Every day in this game of baseball, you see something you never saw before." Still I might have thought history contains all it needs about Stengel, the quintessential figure on all four New York teams – “the Brooklyns,” the Giants, the Yankees, and the Amazing Mets. Casey let a sparrow fly out from his doffed cap as a Dodger; he hit an inside-the-park homer for the Giants in the World Series; he won 10 pennants in 12 years as the Yankee manager; and he managed the Mets for their first four seasons. Now, my friend Marty Appel has found good new stuff about Casey – and his times – in a new book, “Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character,” to be published by Doubleday on March 28, just in time for a new season. Appel uncovered some gems about Casey’s childhood in 19th Century Kansas City and his playing career in a Brooklyn so long ago there were no hipsters. He has used computerized libraries and files not available to previous biographers of Stengel, including the late Bob Creamer, a luncheon companion of ours. For example: Appel discovered that the Stengel family lived in the same neighborhood as Charles (Kid) Nichols, a Hall of Fame pitcher who won 361 games from 1890 to 1906. When “Dutch” Stengel was a rambunctious teen-age ball player, the old pitcher advised him to always listen to his managers. “Never say, ‘I won’t do that.,'" Kid Nichols said. "Always listen to him. If you’re not going to do it, don’t tell him so. Let it go in one ear, then let it roll around there for a month, and if it isn’t any good, let it go out the other ear.” This is wonderful advice. I spent a lot of time around Casey from 1962 to 1965 -- in his office and late at night in bars – and I never heard him mention Kid Nichols. But I now know that Kid Nichols helped Casey learn as a player – and teach as a manager. Appel tells a great story (new to me) about a prospect named Mantle, who could run but was slowed down by his habit of looking at the ground. Stengel told Mantle he was no longer playing football in Commerce, Okla., that the major leagues had groundskeepers who created smooth base paths and that he should keep his eye on the ball and the fielders. It made Casey crazy to see blank looks on players. The Old Man also tried to teach “my writers,” in murky soliloquys very late at night. Just when you were about to give up (or doze off) he would grab you with a stubborn paw and say, “Look, you asshole, I’m trying to tell you something.” Appel has learned about Casey’s wife, Edna Lawson Stengel through an unpublished memoir made available by Edna’s niece, Toni Mollett Harsh. Apparently, the Stengels considered themselves too old – in their thirties – to start a family, but they were affectionate toward the wives and children of some of the younger players. (He bought a ginger ale for my oldest child, Laura, in the motel bar in Florida after his managing days. She remembers it vividly.) I learned something else. Appel amends the legend that Stengel’s wealth came through his wife’s family, which owned a bank and businesses in Glendale, Calif. In fact, young Casey paid attention to a teammate from Texas who talked him into buying oil rigs. Casey often barked, “You make your own luck.” Marty Appel reminds us all that Casey Stengel made his own luck. We had 60 degrees Wednesday, a whiteout Thursday, frozen rain Sunday. But some of us take heart from the first robins of spring – pitchers and catchers sighted down south.

Then there are advance copies of baseball books, just being distributed to lucky media types like me. My first CARE package was a literate and knowing little gem, “Off Speed: Baseball, Pitching, and the Art of Deception,” by Terry McDermott, from Pantheon Books, which will be on the shelves in May but has already rejuvenated me. McDermott, a writer on other serious subjects like terrorism, is also a baseball buff, stemming from childhood in Cascade, Iowa. He describes his first big-league game – a Yankee doubleheader at Comiskey Park, June 28, 1959, on a road trip that reminds me of a boy’s rambunctious bus pub crawl with Welsh elders in the classic Dylan Thomas short story “The Outing.” Once a year, McDermott writes, the men of Cascade “would charter a Burlington Line train – who knew you could even do this? -- out of East Dubuque, Illinois. They’d fill the train with Knights of Columbus, cold ham sandwiches, and Falstaff beer – or maybe Schlitz in a good year – and head east. My father, known to everyone as Mac took me along as an early birthday gift.” McDermott adds: “It was my first game, my first train, my first taxi, my first bus, my first time seeing grown men pass out drunk.” Also, his first time seeing and hearing black Americans on the South Side of Chicago. The hold of baseball -- a rural game played in urban settings -- reminds me of the great book, "The Southpaw," by Mark Harris I wrote about it for opening day in 2005: The young lefty from upstate New York goes to his first game in the big city where he will one day pitch. In his first pilgrimage to another great baseball town, McDermott witnessed Yogi Berra catching both ends of a doubleheader loss. The great source Retrosheet does not allude to it, but McDermott is sure he saw a foul pop drop untouched near Berra just before an Al Smith homer, 58 years ago. Fans remember stuff like that. Cascade is a small town, 15 minutes from where Kevin Costner wandered in the corn fields in “Field of Dreams,” and it fielded a weekend team which won 64 of 65 games one season. The star pitcher was obscurely known as Yipe; every male in Cascade had a nickname. McDermott could have written only about the enduring pull of baseball in a small town (which still has a team) –– and that would have been fine, in fact, beautiful. But the book does much more, economically – the dissection of a perfect game by King Felix Hernandez of the Seattle Mariners on Aug. 15, 2012 – sunny day game after a night game, McDermott duly notes. He has taken four full seasons to reconstruct that game, talking shop with the scattered principals, lifers who remember every pitch. He uses each inning to illustrate one of nine different pitches in baseball’s arsenal. Some of the old masters include Walter Johnson, Three-Finger Brown, Candy Cummings, said to be the inventor of the curveball, and Cascade's own Urban (Red) Faber, Hall of Famer and next-to-last (legal) practitioner of the spitball. And more: McDermott was a ballboy one night in Cascade when Satchel Paige 56 going on 1,000, pitched a few innings. Satchel winked and asked the boy to please not clean the dirt off the balls being rotated back into the game. Let’s have some fun, Paige suggested. This book taught me some things: hitters who start 0-1 in the count bat .230 on that at-bat but hitters who start 1-0 bat .275. Thirteen pitchers have had their perfect game disrupted with two outs in the ninth. And, in this affluent era when barely-used balls are tossed to the fans, the average game consumes 120 balls. McDermott provides touching digressions about the numerous shoes in his daughter’s closet, and the time his headstrong dad cooked meat on the lid of a garbage can. (It was for the dog, he quickly adds.) He has a great ear for the verbal excursions and minutiae and great truths that baseball produces, more than any other sport. “Off Speed” will be out soon enough, but my privileged early peek assures me: baseball lives. When Melania Trump “borrowed” chunks of Michelle Obama’s words last summer, she was found out in the flick of an iPhone.

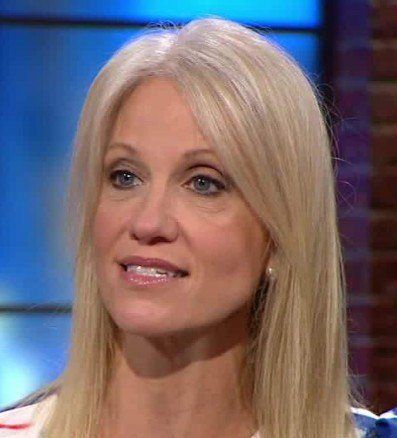

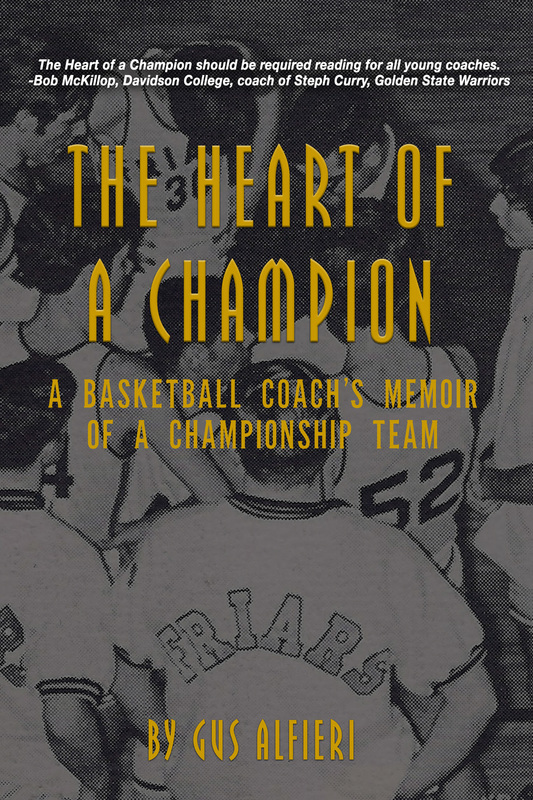

She didn’t seem to know the difference. Public figures are often caught using stuff from other people. Remember Joe Biden "borrowing" some material back in law school? And Tony Blair apparently re-channeling stuff from the movie “The Queen,” about him and Queen Elizabeth? The Web makes that harder and harder. Now it turns out that Monica Crowley, a former Murdochite on-air personality, scheduled to explain the complexities of national security for the Trumpites -- has used as many as 50 segments for a book under her name. In this day and age, wouldn’t you think she would know caution, if not shame? I say this, because just about everything is out there on the Web, easily checked. Research no longer is limited to dusty books or files from the back corners of a library. I know this, because in preparation for a talk I was thumbing through the 522 pages of “Look Homeward, Angel,” by my favorite author, Thomas Wolfe. I wanted to refresh my impressions of a few sweet passages but after an hour of enjoyable searching, I came up empty. Go to the laptop, dude. ---I knew there was a passage about a scholarly nun, examining a book at the bedside of a sleeping girl in a boarding school. I typed in “nun” and “book” and “sleep.” Found it. Still sweet and respectful. ---I knew Wolfe’s father liked to tell about being a 13-year-old, sassing Confederate soldiers in his village near Gettysburg. The Web reminded me that this epic section had been exorcised by Maxwell Perkins, Wolfe’s renowned editor, only to be revived decades later in an expanded version called “O, Lost.” I’ve requested it from our wonderful town library. ---I knew Wolfe often wrote about the lavish meals his father craved in his wife’s parsimonious boarding house in Asheville, N.C. – loving references to butter slathered on fat lima beans. I typed in a few words. Bingo. One would think that somebody writing today – even a Foxite news person – would have a little fear about lifting bunches of stuff from other sources. But anything flies these days. Just ask Kellyanne Conway, designated explainer and lookalike of the aforementioned Monica Crowley. Conway. says stuff with a straight face. I certainly would not expect Trump to understand these subtleties. * * * Meantime, has anybody else noticed that Crowley and Conway appear to have been separated at birth? And the seething Gen. Mike Flynn, who used to spew patently untrue “Flynn Facts” to subordinates, resembles the paranoid Col. Bat Guano, who shoots his way into the office in “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” – now coming true, in a universe near you. Gus Alfieri still writes his own stuff – a rare accomplishment for any coach.

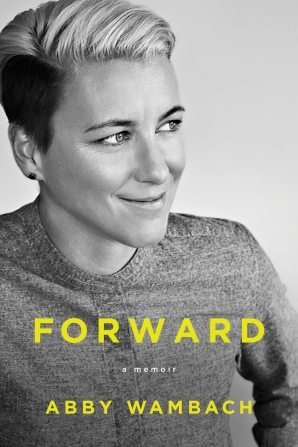

Alfieri won a championship as a college point guard and he coached a state high-school champion and he has, quite admirably, made himself into an author. Alfieri’s latest book, just in time for the season, is “The Heart of a Champion: A Basketball Coach’s Memoir of a Championship Team” – about the 1973-74 season when he took St. Anthony’s from South Huntington, Long Island, to the new (and technically unofficial) state championship. But the book could be about many coaches and many teams that jelled in that one magical year. Alfieri was a hard grader as a coach and he remains one as a writer. He describes moving into coaching on Long Island, which was just beginning to produce basketball talent in the early 1960’s: Larry Brown of Long Beach and Art Heyman of Oceanside, two strange birds from neighboring towns, took their personal animosity to North Carolina and Duke, respectively. But they were seen as anomalies. When Alfieri, a Brooklyn boy, began coaching out on Long Island, Lou Carnesecca, who had replaced Alfieri’s beloved Joe Lapchick at St. John’s, wondered out loud if they were still using a square ball out there. (I had the same smug feeling, as a Queens boy, when I worked at Newsday in the same period.) Alfieri describes a golden age way out there on the Island – Julius Erving and Mitch Kupchak and all the future coaches like Rick Pitino and Jim Valvano. He also recalls a coach or two he thought was weak and he remembers taking over at St. Anthony’s and feeling that some of his upperclassmen were holding back, possessive of their starting positions. Probably a few former players, well into middle age, will not be amused at Alfieri’s memories. But he built his own system, as coaches do, and he turned St. Anthony’s into a powerhouse. His role model, as always, is Joe Lapchick, the courtly and angular coach of the Knicks and St. John’s, who advised his players to “walk with kings.” That first book clearly a labor of love, glows with the presence of Lapchick, and this new book retains much of the old coach. As he coaches big games, Alfieri often refers to what Lapchick might do. In a tense locker room at the final game, a player asks to speak. Alfieri likes control, but his inner Lapchick guides him to let the senior address his teammates. Alfieri is a hard worker. For his Lapchick book, he found a former teammate who had been guilty of dumping games and, after many decades, he asked him “why?” In this new book, he does his homework and recreates the key plays in the rally over the very loaded Lutheran High. (There is also good stuff about the machinations in creating the tournament, by the wily administrator Jim Garvey.) But Alfieri’s work does not end with that championship and a subsequent state title. After coaching, he became a teacher, earned a doctorate, ran a basketball camp, and every November he organizes a charity luncheon, giving high-character awards to deserving coaches. I always love the stories by the female coaches, who built their own traditions with minimal budgets and maximum heart. This year’s award luncheon is Nov. 18 at the Wyndham New Yorker, across from Madison Square Garden. For information: http://www.characteraward.com/ Gus Alfieri will be speaking about his book at the wonderful Book Revue in Huntington, Long Island, on Oct. 18 at 7 PM. For information: http://bookrevue.com/GusAlfieri.htm My previous piece about Alfieri and his Lapchick book: http://www.georgevecsey.com/home/honoring-gus-alfieri-player-coach-writer For further information: www.gusalfieri.com. Abby Wambach hurled herself into the scrum, raised her forehead above the crowd, and drilled home more goals than any player in American soccer history.

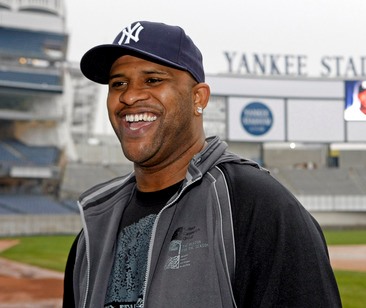

She took her hits, including a gruesome broken leg, but remained a towering presence even as a role player and leader in her last Women’s World Cup which she helped win in 2015. Now she has revealed more about herself in a brave and revealing new book, “Forward,” written with the help of Karen Abbott. She talks about her use of alcohol and pills, and says she is clean and sober now. (Disclosure: The editor of this book at HarperCollins is the talented Julia Cheiffetz, who brought a better baseball history book out of me than I ever could have done on my own.) Wambach also talks about realizing she was attracted to women, and how she came out to family, friends, teammates and the public. More than any athlete I have read about, Wambach is open about the touches and glances and courtships and breakups in her private life – plus, how her moods have disrupted her marriage to a former teammate. Wambach also talks about the challenges of being large and athletic from an early age – taking the hits on the field, and off. At least once in college she jumped a football player who had made a comment about her. The injuries and stress are right out of Peter Gent’s book, “North Dallas Forty,” in which football players need this pill to get going in the morning and that pill to go out on the practice field, and that other pill to mask the pain afterward. The pain of soccer and the pain of her inner life seemed to overlap for Wambach, although she was fortunate to have a strong family, a close male friend since college, and several former companions and teammates who came to realize her torments. In one of the strongest moments in the book, Wambach’s team roommate, Sydney Leroux, married and “straight,” realizes Wambach is crying in the next bed, and removes her ear plugs and then takes “careful steps to my bed. She lies down and makes room for herself, crying right along with me.” Leroux and others offer wise intervention, but is it enough? After several attempts at sobriety, Wambach stops drinking and abusing pills, which is where the book ends. Having written a book with an alcoholic baseball player, Bob Welch, I am a strong supporter of organized rehab. Bob went through an emotional month at a center, and I later spent a week at the same clinic so I would understand Bob and the process. The first step is admission of powerlessness. I think Wambach is saying she was powerless over alcohol and pills, so I wish she had put herself in an organized setting, to be confronted by trained counselors and recovering addicts and friends and family. As she knows from her 184 goals, the best headers come from a buildup and skilled passes from teammates. Abby Wambach is now doing television commentary and making speeches, being presented as a role model. I am rooting for this complicated and passionate person, as her story goes “Forward.” You already know who the ridiculous is. So let’s start with the sublime. I was in the library the other day at the “New/Non-Fiction/14 Days Only” section. On a lower shelf, I spotted a book of essays by Annie Dillard, “The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New.” Somehow, I had gotten to be this old without ever reading anything by Dillard, so I picked up the book, and opened it in the middle, to a chapter entitled “The Weasel” “The weasel is wild. Who knows what he thinks? He sleeps in his underground den, his tail draped over his nose. Sometimes he lives in his den for two days without leaving.” Needless to say, I checked it out. The weasel essay, six pages long, includes a 60-second encounter in the woods when Dillard and a weasel locked eyes. The essay also includes the tale of an eagle that tried to carry off a weasel, and got more than it expected. The essay become an exhortation to grab life – whatever life is – with your jaws, and not let go. That is pretty much what Dillard does in her writing, and in her life, by her own testimony. In one section, "An American Childhood,” previously published, she races through her family and her church and her boyfriends and her life. Required reading for teen-agers. I was knocked out by the two final essays. One was about sand, and geology, and the Jesuit priest-paleontologist, Teilhard de Chardin, and love. The final chapter by Dillard, a convert to Catholicism, was alternating segments about what she called the modern "hootenany" Mass and doomed polar explorers who went off unprepared. It ends with a fantasy of the two themes overlapping. I am now a fan of Annie Dillard, maybe even a groupie. * * * The second book continues the furry, feral theme, considering the muskrat Donald Trump carries around on his head and in his head. The book is “The Making of Donald Trump,” by Pulitzer-Prize-winning David Cay Johnston, seen often on the Web and the tube, warning us, “The Trumpites are coming! The Trumpites are coming!” The book hit No. 15 on the Times best-seller list last week. Johnston is an investigative reporter, one of the best, and has been on the scent of Trump and the muskrat for decades. He has put together verifiable details of the way Trump does business – the Polish immigrants who tore down a landmark building at nights, without safety precautions or attention to artwork; the vendors who got stiffed by Trump, the garish casinos in Trump’s name without his having any knowledge of how gambling works, the threats, the suits, the welching, and the lies about women he never dated. Johnston’s book should be read – but won’t be -- by the fact-averse minority that considers Trump the great white hope. Weasels sí, muskrat head no. Until last fall, Bob Welch and C.C. Sabathia had one thing in common – the Cy Young Award, as the best pitcher in his league one year.

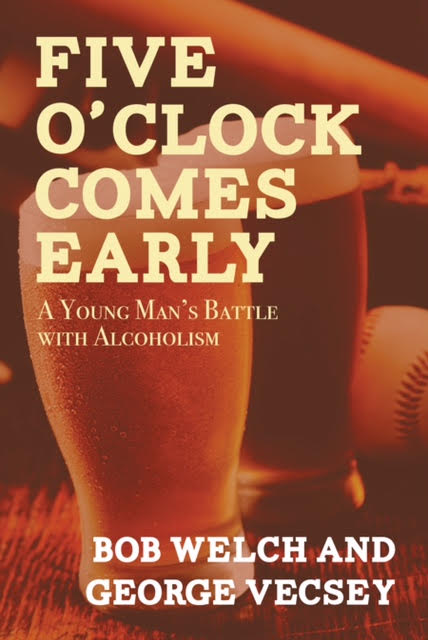

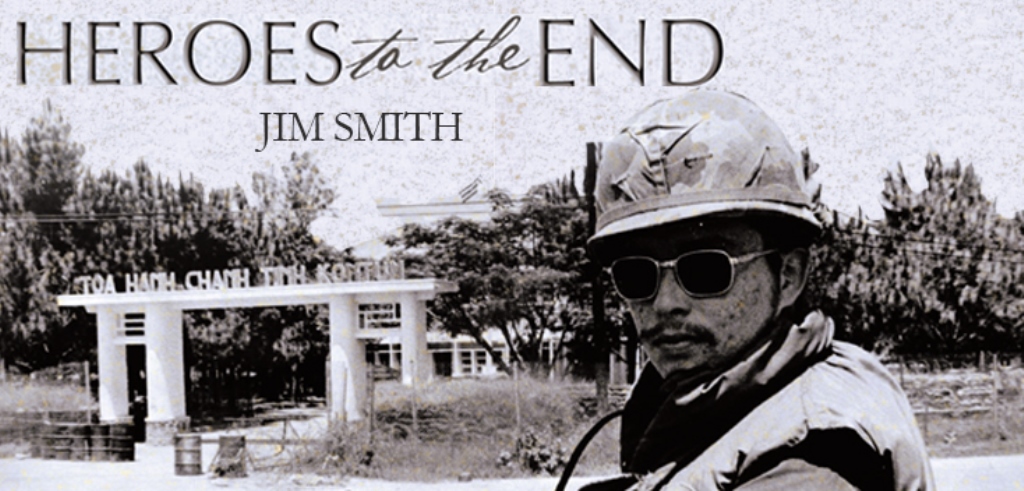

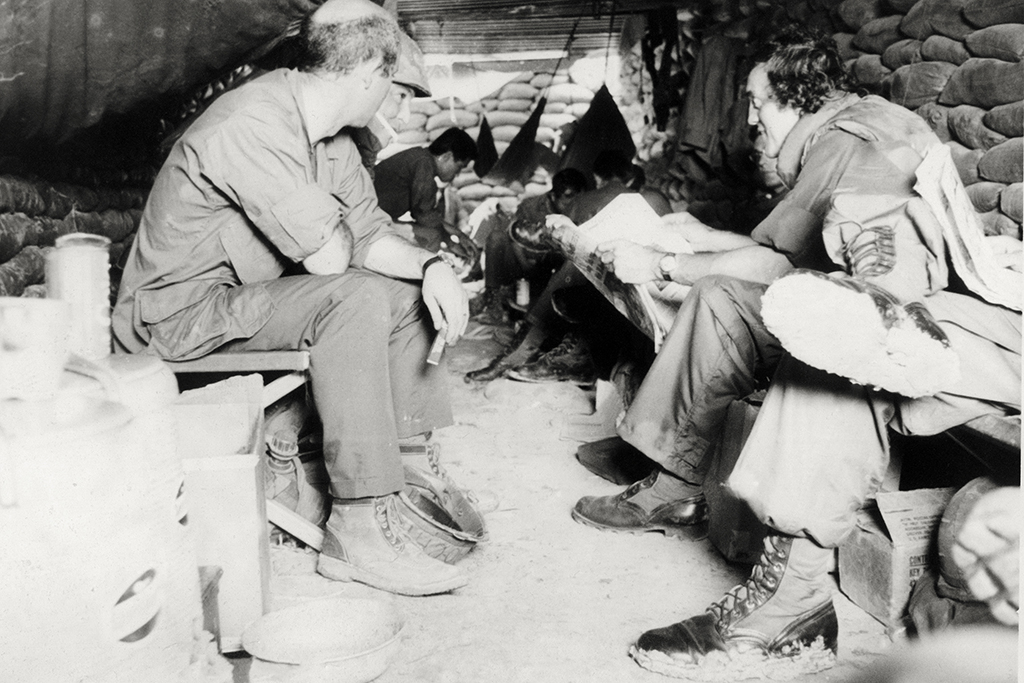

Now they have something else – rehab. Near the end of last season, Sabathia sought out a treatment center to face the addiction to alcohol that he was ready to acknowledge. “I started reading a lot while I was in rehab,” Sabathia wrote on March 7 in the Players Tribune website. “The first book I read was called Five O’Clock Comes Early. It’s by a former major league pitcher named Bob Welch, and it hit so incredibly close to home. Bob became a professional when he was only 21 years old and dealt with a lot of the same anxieties that I had felt, so he’d turn to alcohol for confidence. He ended up checking into a rehab facility, and when he came out on the other side of treatment he was a changed man. He ended up going on to have a great career after he got help.” Riley Welch read Sabathia’s story and alerted me. Riley is a ball player himself, a college and minor-league pitcher, now coaching pitchers in Honolulu. He’s always been proud of his dad, who died suddenly in 2014 at the age of 57. “It brings my family and me great pleasure and joy to see that now, almost thirty years after Five O'Clock Comes Early's initial release date, it is still helping someone live a healthier life,” Riley wrote to me. “I’m very proud that the book was able to provide inspiration for someone during a rough period in his life.” In 1980-82, before Riley was born, I helped Bob write his book, when his rehab was still raw and he needed to reinforce it every day – to verbalize that he was choosing not to drink when the guys were getting hammered in the back room of the clubhouse. Over the years, I’ve received dozens of letters from readers – almost always men – who said they were staying sober – that day – because of what they learned from Bob. I don't know if C.C. Sabathia knew Bob Welch. Bob won the Cy Young in 1990 with Oakland; Sabathia won his in 2007 with the Yankees. But baseball is a fraternity with frequent lodge meetings, and Sabathia grew up in the Bay Area, Bob’s long-time home, so maybe they did know each other. More importantly, Sabathia is taking an example from a pitcher who saved his career, his life, when he was just getting started. I can only imagine Bob’s enthusiasm when he heard that a colleague had taken the big step. Bob’s book was reissued in electronic form last year, with a new chapter I wrote after Bob’s passing. C.C. Sabathia’s testimony reminds Riley Welch that his dad is with us, with lessons to teach anybody with “the problem.” Riley added: “I know my father would be proud of C.C. for getting help when he needed it.” * * * Riley also enclosed a recent story by Barry Bloom, about how Bob Melvin, the Oakland manager, has put the bench commemorating Bob in a prominent spot at the spring ballpark. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/166395958/as-bob-melvin-appreciates-bob-welch-memorial  John Paul Vann, July 2, 1924 - June 9, 1972. Photo by Jim Smith John Paul Vann, July 2, 1924 - June 9, 1972. Photo by Jim Smith Jim Smith and I used to goof around in the Newsday sports department. He was going to college and covering high-school sports, just as I had started. Then he came up with No. 34 in the draft lottery and wound up in Vietnam, first as a typist, then on guard duty, then covering the war for Stars and Stripes. When he came back, he was different. They all were, the ones who came back. Years later, in 1991, my wife and I were in Vietnam through her volunteer child-care mission, and I came back with new friends and mostly good memories. I saw Jim at a game, and offered to show him photos. He shuddered. Didn’t want to go there. Now Smith is 67 and retired, and has written a touching and valuable book, “Heroes to the End: An Army Correspondent’s Last Days in Vietnam,” published by iUniverse, also available on e-book. The words come back. Tu Do Street. Hootch. Charlie. Tunnels. ARVN. Words from history. Words people live with. Jim is very clear about the journalism he produced, under orders to write only positive stories. But he has fleshed out the details with memories and notes he stashed and letters he sent home. He makes it clear that he was no hero. He had only four months up close to the fighting, in 1972, when casualties had been downsized, and he only began inching closer to combat near the end, so he would know what it was like. He came under fire twice, never fired a shot. Most Vietnam books go for the big picture – how LBJ and McNamara and Westmoreland and so many others ignored and misrepresented and lied. Smith’s book concentrates on the people who did the dirty work; some thought they should go harder, others thought it was all a waste. Smith fluctuated from dove to hawk. He kept his hair fairly short, so officers would give him stories. He concentrates on the mundane, the down time, the bitching, the carousing, but the old horrors creep in, nevertheless. Mostly he saw the humanity – some young Americans who discovered they were quite good at firing a machine gun from the door of a helicopter or seeking out Vietcong in the brush. They were warriors. Others were not. Smith was a reporter, glad to get back to base, to Saigon, to his apartment and civilian clothing and the girlfriend he almost brought home with him. The closest thing to a big picture comes from meetings with Lt. Col. John Paul Vann, who questioned the war and later was the hero of Neil Sheehan’s Pulitzer-Prize winning book, “A Bright Shining Lie.” “I had more respect for Mr. Vann – for that is what I always called him – than for anybody else I met in Vietnam.” After Vann died in a helicopter crash, Smith held back from punching a captain who said Vann had been a showoff. Smith displays admirable journalistic curiosity about the South Vietnamese, Montagnards and South Koreans he observed in combat. Then he came home to cover local news and we resumed goofing around during a fractious school-board feud in Great Neck. (How petty it must have seemed to a reporter back from war.) He married a colleague from Newsday, Lynn Brand, and they have a son, Peter. In retirement, Jim Smith is on the board of United Veterans Beacon House and is donating the profits from his book to veterans’ causes. He served. As he reminds us of that war, I would say he is inching closer to hero status all the time. The latest output from the family is by David Vecsey, who normally spends days and nights editing others but occasionally exercises the writing part of the brain.

David made a journalistic foray into the heart of darkness known as sports fantasy gambling. He emerged with his shirt still on his back, plus a story describing mood swings based on the doings of athletes, some previously unknown until he drafted them. His article on Gothamist: http://gothamist.com/2015/11/30/daily_fantasy_sports.php Then there is my wife’s cousin, Paul Grundy, MD and MPH, IBM's Global Director of Healthcare Transformation. He and two colleagues have written an entry-level primer on the mysteries of health care including trends toward industrial-size health complexes, concierge doctors and the vanishing of the actual family doctor. (You noticed.) The book is: Lost and Found: A Consumer’s Guide to Healthcare by Peter B. Anderson, Paul H. Grundy, MD, and Bud Ramey (contributor). Next is Laura Vecsey, former sports columnist and political columnist, currently covering the U.S. women’s soccer team, World Cup champs, on their victory tour of America, for Fox. Her latest article on Carli Lloyd’s candidacy for player-of-the-year: http://www.foxsports.com/soccer/story/carli-lloyd-and-jill-ellis-have-chance-to-make-more-history-for-uswnt-113015. The family legal wing is in Pennsylvania, where Corinna V. Wilson is the energy behind the consulting firm Wilson500. Corinna helped write the Pennsylvania right-to-know act of 2008, and she flexes her writing skills when that important law is threatened by nervous politicians: http://pafoic.org/2015/02/commonwealth-court-decision-in-psea-case-eviscerates-right-to-know-law/ Finally, my book that has done the most good for others has been revived. I helped Bob Welch write “Five O’Clock Comes Early: A Young Man’s Battle With Alcoholism,” first published in 1982 soon after Bob’s return from a rehab center, to be a star pitcher for more than a decade. My friend Bob passed in 2014 – a lot of us are still reeling from it – but his book, updated, is a handbook for anybody, particularly the young who cannot believe they are powerless over addiction. I’ve heard from people who say Bob's book helped save a life. The new e-book version is from Open Road Media: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/five-oclock-comes-early-bob-welch/1120190861#productInfoTabs Fortunately, some of us also have visual talents. Marianne Vecsey is a painter (above) and Anjali takes photos with her smartphone (below) Nice to be re-discovered.

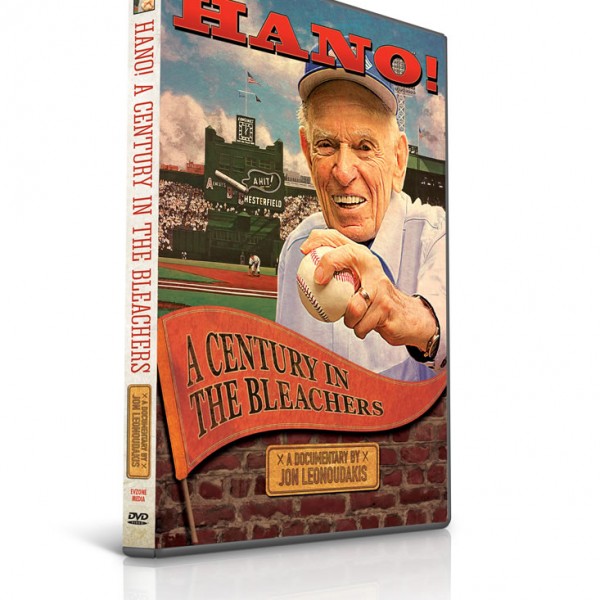

For many decades, Arnold Hano was one of the best magazine writers in America. He is best known for his slender jewel of a book, “A Day in the Bleachers,” which he wrote on impulse after witnessing Willie Mays’ catch in the 1954 World Series. But he is so much more than that, a 1930’s guy who still talks about “the social contract” – the relationship between individuals and society. “He met and talked with Babe Ruth, JFK and John Wayne, saw Mays’ iconic catch, Larsen’s perfecto, and successfully battled racism, land developers, big corporations, and the federal government. says Jon Leonoudakis, a California-based film-maker who was so taken with Hano’s body of work that he has put together a documentary about him. “His story has flown under the radar of popular culture for nearly a hundred years -- until now,” Leonoudakis added. Hano is 93 and living in Laguna Beach, Calif., with his wife Bonnie. They have been together for 67 years as he wrote about protecting wildlife from Disney and other developers. Two baseball stars, Orlando Cepeda and Felipe Alou, testify in the film about Hano’s fair depiction of Latino players. The Hanos also demonstrated against prejudice in their adopted beach town. And they joined the Peace Corps in their 60’s and built schools in Costa Rica. The film-maker became entranced with Hano and began interviewing him, with Hano insisting there was no story. (Larry David would play him in the bio-pic.) Leonoudakis rounded up a gaggle of admiring colleagues (including me) and added an artistic blend of original jazz, original art (not the usual sports schlock) and touching photos, including Arnold and Bonnie Hano, young and old. The couple was back in New York the other day (at Bergino Baseball Clubhouse) to publicize the documentary. She was there on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, Sept. 29, 1954, when Hano – without any assignment or credential -- decided he would walk to the Polo Grounds for the opening game of the Series between the Giants and Cleveland. Bonnie Hano, as wives do, told her husband not to be silly. He was never going to be able to walk up and buy a ticket. He did not listen to her, and stood two hours on line and paid $2.10 (he remembers all that stuff) to sit in the bleachers, the left-field side, so he could call balls and strikes from 500 feet away. He started keeping score -- that’s what people did at ballparks before selfies -- and taking notes in the margin of his paper (The Times.) Top of the eighth. Tie game. Nobody out. Runners on first and second. Then Willie Howard Mays began running toward Arnold Hano to track down a mammoth drive by Vic Wertz. Hano watched as Mays, arms outstretched, caught the ball as it soared over his shoulder, and then, in one fantastic powerful whirling motion, turned and dispatched the ball to second base, on a powerful arc. Larry Doby did move from second to third, but Al Rosen had to go back to first because of Mays’ howitzer shot. . (“Wertz flew to center field,” tersely reports the play-by-play on the invaluable Retrosheet.) Hano watched the Giants win, 5-2, on Dusty Rhodes’ homer in the 10th. Then he went home and typed up his report, which turned into a small book that did not sell much at first but has become one of the classics of the sport. I wrote about the book on the 50th anniversary of the Mays catch, in 2004: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/29/sports/baseball/hazy-sunshine-vivid-memory.html?_r=0 Arnold and Bonnie Hano downgrade the book as something short of literature. They do have their opinions, which Hano has injected into the copious details and color and quotes -- one of the best dossiers of sports magazine articles, ever. Now he has been captured in a knowing 53-minute film. Leonoudakis is seeking space on television and festivals and archives devoted to baseball – and journalism, and America. The film is film is available on DVD from the film’s website: http://hanodoc.com/product/hano-dvd/ It is also available for streaming: www.reelhouse.org/jonleonoudakis Oh, yes, and check out the cover art (above). It figures in the delightful coda to the documentary. Carl Hubbell. That’s all I’m saying. Written before Game 1: Somewhere, sometime, Colon helps win a game in long relief, like Ryan in 69 and Fernandez in 86. Royals play the game right -- good energy, make contact. Mets in 7.  Staging a Revival in Chicago Staging a Revival in Chicago I admit it. I blinked when I saw the title of Steve Kettmann’s book around Opening Day: “Baseball Maverick: How Sandy Alderson Revolutionized Baseball and Revived the Mets.” It wasn’t the main title. I was willing to find out how Alderson was a maverick (computers, Mr. McGuire?) but what about the subtitle, the “Revived” part? I was intrigued by Kettmann’s choice of that R-word as the Mets gamely staggered into July -- subs, AAA players, walking wounded, veterans, a few live arms, all playing hard for Terry Collins. Then in a space of two weeks, darned if they were not revived, by Alderson, by Collins, by Cap’n Wright, by Cespedes, by trades and demotions and recuperations. But you know all that. Writers care about titles -- and subtitles. I have been blessed with all-stars as book editors over the years, too numerous to mention, except for the most recent. When I was writing my soccer book, Paul Golob of Holt (working with Times Books) noticed my scattered mentions of the dictator of FIFA, Sepp Blatter, and his collaborators. “Don’t forget to include the dark side,” Golob suggested. I agreed, and he came up with the title: “Eight World Cups: My Journey Through the Beauty and Dark Side of Soccer.” As FIFA's legal charges added up, was I glad the editor had prodded me. I could go on talk shows and intone those book-writer words, “As I say in my book….” I knew Kettmann, based on the Left Coast, had access to Alderson from covering the Oakland A’s. I asked Kettmann how he came up with his title and subtitle and he replied: It's funny about subtitles. We tend to think of them as nearly invisible, like the subtitle to "One Day at Fenway," my first book, which was "A Day in the Life of Baseball in America." I'm not sure a single person ever cited that subtitle or made a point of it. Then again, that was 11 years ago, long before the age of Twitter. I spent a lot of time going over the title and subtitle for my Sandy Alderson book with Jamison Stoltz, my editor at Grove Atlantic. We thought if there was going to be controversy, it would concern the title, "Baseball Maverick," since "Maverick" is a word that can mean different things to different people. Some, we knew, would picture Tina Fey as Sarah Palin, talking about getting all "Mavericky." But I took the title from a quote given to me by Billy Beane, which he clearly meant as a tribute to his former mentor and to me, the important meaning was the original one, going back to the rancher Samuel Maverick, who left his cattle unbranded, meaning he would end up with all unbranded cattle, and he developed a reputation (rightly or wrongly) for being a free thinker who was just a little smarter than everyone else. As for the subtitle, I thought then and think now that it was inarguable, at least among people interested in having an actual discussion, as opposed to flinging free association at each other on the Internet in short bursts. Alderson was one of a small group that "revolutionized" baseball and, given where the Mets had been in recent seasons, no question that by 2015 the team had been "revived." That was the consensus at baseball's annual winter meetings in December 2014, and that was my view: The Mets had too much dominant young starting pitching not to make a major leap forward, and Alderson had always said that when they had enough talent to be competitive in the postseason, they would make midseason upgrades to improve further. I could not have known the Mets would have the magical season they have, but I was sure they'd make the playoffs. I was sure they'd be playing meaningful games into October - now they might be playing them into November. Playing into late October, I think you would agree, qualifies as "Revived." . I associate Roger Cohen with his skateboarding on a small ottoman, at risk of a broken neck, to celebrate a Chelsea goal on the tube.

I associate Tracy Kidder with his long legs racing around the bases on a softball party, decades ago. Yes, serious writers, have their sports side. I just caught up with books by both of them, touching the deepest issues in the world – genocide, inequity, identity. Cohen’s book is “The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family,” published this year by Alfred A, Knopf. It is partially about the imbalance in many members of his family, which has made the trek from Lithuania to South Africa and onward. His mother became troubled shortly after emigrating from South Africa to England early in her marriage and never recovered. The book also delves into what it means to be Jewish in a dangerous world, with some of his family escaping ahead of the murders in Europe, making a success in South Africa, but never feeling quite accepted in England – hearing the discreet lowering of voices and being described as “Jew” rather than “Jewish.” Later Cohen re-settled, for reasons he came to understand. “One day, banking over New York City on the approach to LaGuardia, watching the serried towers of midtown, a single word welled up from deep inside me: home.” Cohen writes of the city of “incomers.” He has become one of journalism’s most staunch defenders of the marginal. Tracy Kidder has also been exploring corners of the world, ranging from the emerging computer society to poverty in Haiti, often seeking people who take chances, who make a difference. His idealism is on display in his 2009 book for Random House, “Strength in What Remains: A Journey of Remembrance and Forgiveness.” Kidder traces the wandering of a people, and an individual, Deogratias Niyizonkiza, a member of the Tutsi tribe in Burundi. Barely escaping a bloodbath while in medical school, Deo survives in Africa the same way some of Cohen’s family survived in Europe – through the grace and courage of others. In Kidder’s book, the man called Deo lands in New York, is helped by a baggage handler named Muhammad, a former nun, and an intellectual couple from Greenwich Village – the parallel layers of strength that work so often in this city. Kidder recreates Deo’s survival in Burundi, and moves toward the present, with Deo, now a poised 40-something New Yorker, running a medical facility back home in Burundi, where the prevailing custom is to not remember terrible things that have happened. My conclusion is that there is no such thing as light summer reading. These books by Cohen and Kidder would make me think and care in any season.  Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Lauren Bacall loved this box. She told Cornell's biographer, "I wish I had it." Joseph Cornell was already well known for his collages in small boxes during the mid-50’s when I was in high school. Our busy road (188th St.) dead-ends into Utopia Parkway just south of Cornell’s home, maybe three miles from my childhood home, but I don’t remember my cultured friends and teachers ever mentioning him. The Jamaica High School paper interviewed famous New York people and probably could have gained an interview with this introverted soul but, like me, the editors had not discovered him. I am thinking about Cornell because my daughter Laura just took his biography – “Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell,” by Deborah Solomon -- out of the library. It’s been around since 1997 yet it took me this long to read about this artist who lived with his widowed mother and his younger brother who was limited by cerebral palsy. Cornell is stereotyped as the hermit who stayed home on Utopia Parkway, caring for his mother and brother, and when the world quieted down at night he would snip others’ work and blend them with memorabilia of France, or incongruous mundane objects to create new form. I once met Louise Nevelson at a party. She made us roar by describing how she bellied into a dumpster to retrieve some artifact she could use in her sculpture. Cornell was no less driven. Somehow, he managed to work at menial jobs in the city, to support his family, while haunting the art galleries and bookstores at lunch hour and then take the train back to Flushing. People called him a a recluse but really he was a Zelig of an Outer Borough who knew Dali and Duchamp and de Kooning. Tony Curtis came to his house in a limo! Cornell sought out ballerinas and actresses, shopgirls and students. Audrey Hepburn sent back one of his boxes. Susan Sontag enjoyed his company. His work celebrates sensuality, small hotels in Paris, birds, mystery, beautiful women. He died in 1972 at the age of 69. The author informs us that his short, intense crushes were "platonic." I liked Cornell even better when I read that he loved the haunting music of Erik Satie, who lived in a squalid little flat in the outback of Paris. Cornell's boxes and Satie's compositions are a perfect fit. I have loved Cornell's work since my wife, an artist, introduced me to museums and galleries. Maybe I am particularly affected because I grew up in Queens, in a narrow house much like Cornell's. Next door, a few feet away, two brothers, waiters named Rocco and Luigi, practiced the scales and the arias on summer afternoons with the windows open, before going to work. In Queens, we knew that “it” was just a subway ride away. And all that time, maybe three miles up the road, Joseph Cornell was caring for his family and making his boxes. I was watching the Tour de France on Tuesday morning as it swept through the city of Charleroi, in Belgium.

My mind went back to a nasty morning in 2004, at a staging area in the very same Charleroi, when I had a taste of the grim war being fought by Lance Armstrong’s minions. Totally by coincidence, I am reading the new book about the battle of Waterloo, by Bernard Cornwell. Another conqueror also passed through Charleroi that fateful month of June, 1815. His name was Napoleon Bonaparte. So now they are fused in my mind, the man on horseback, the man on the bike. As the Tour began in 2004, a new book came out, “L.A. Confidentiel: Les Secrets de Lance Armstrong,” by David Walsh and Pierre Ballester, containing many accusations of doping by Armstrong and his team. The book was only in French. I bought a copy at the Brussels Airport and was reading it as the Tour began in Liege. One of the most convincing sections was about an Irish masseuse, Emma O’Reilly, who recalled how Armstrong had tested positive for steroids in 1999, only to have a doctor file a note saying Armstrong had been using a form of steroids to combat saddle sores, an occupational hazard. If anybody knew whether Armstrong had saddle sores, it would be his masseuse, O’Reilly said -- and he did not. She described the panic in the Armstrong bus about the positive test, until a servile world cycling federation accepted the doctor’s ludicrous note, and Armstrong pedaled onward. I alluded to the negated positive. It did not go un-noticed. That drizzly morning in Charleroi, Armstrong’s lawyer-manager, Bill Stapleton, sought me out as we enjoyed coffee and croissants before the day’s stage began. He pointedly told me that Lance had never tested positive. Yes, he did, I said, for steroids. That was not a positive test, he said. I understood his legal point but more important I realized, these people are serious, and they are going to fight on every point. We all know how that ended, years later, with Lance’s confession on Oprah. I think about him while watching the Tour. I saw him win his last three titles. He was the greatest rider of his time. I suspect just about all of them cheated. I hear he has downsized, in his own private St. Helena. Napoleon also held a staging area around Charleroi, 200 years ago. He had come back from exile and had re-claimed much of the French army and was convinced his decisions would always work out. He would feint one way, go the other way, and rout the English and the Prussians. . But they stood up to him, in terrible fighting, on the road north in an area known as Waterloo. In July of 2004, I spent several nights in a motel near the battlefield but never had time to visit it. I was reading “L.A. Confidentiel” and riding in a press car with two copains and getting the cold eye from Lance’s perimeter defense. Watching the current Inoculation Frolics, I was reminded of my recent reading of the superb biography, “Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman,” by Robert K., Massie.

In the spring of 1767, smallpox was rampaging through Russia. Catherine II, the German-born, French-speaking empress of Russia, saw a beautiful young countess die in mid-May. After that, Catherine took her young son and heir, Paul, into the countryside, avoiding all public gatherings. Catherine was well aware that smallpox vaccination was being done in western Europe and the British colonies. (Thomas Jefferson, 23, the squire of Monticello, had himself inoculated in 1767.) She sent for Dr. Thomas Dimsdale, 56, of Edinburgh, who arrived in August of 1768 and cautiously tried to inoculate other women before the empress, just to prove his process worked. (Massie notes that Dimsdale proclaimed Catherine, 39, “of all that I ever saw of her sex, the most engaging.”) However, Catherine bravely insisted she go first and he took a sample of smallpox from a peasant boy, Alexander Markov, and inoculated the empress on Oct. 12, 1768. She developed the anticipated modest amount of pustules and illness but was back in public by Nov. 1. The doctor inoculated 140 people in St. Petersburg and another 50 in Moscow, including Catherine’s son and grandson. Before Dimsdale returned to Scotland, she rewarded him with 10,000 pounds and a lifetime annuity. By 1800, over 2 million Russians had been inoculated. The final word belongs to Voltaire, as it often does. The French philosopher was a regular correspondent with Catherine, although they never met. Massie writes: “Catherine’s willingness to be inoculated attracted favorable notice in western Europe. Voltaire compared what she had allowed Dimsdale to do with the ridiculous views and practices of ‘our most argumentative charlatans in our medical schools.’” Fortunately, in these enlightened times, we do not have any “argumentative charlatans.” I always accepted William Blake’s observation, “The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction” – until I listened to Michael Jordan one night.

Jordan had just made some amazing aerial maneuver for a dunk in heavy traffic. I cannot remember if it was in the Garden or Chicago, but I was there. Afterward, a reporter asked Jordan how he had invented the move while in mid-air. Jordan normally sneered at “you guys” but this time he doubled up on his derision. “I’ve made that move a thousand times in the gym,” he said, patronizingly. Ever since then – 15 or 20 years – I have been vastly more respectful of repetition, performed by tigers of wrath, working on their moves 100 or 200 times per day in the gym or rehearsal room before they perform in the arena. The value of reps was brought home recently while I was simultaneously reading two books that turned out to have the same message. Practice makes. By sheer accident, I was reading Tim Howard’s “The Keeper,” skillfully co-written by Ali Benjamin, and Daniel Coyle’s “The Talent Code,” which I missed in 2009. As it happens, I know both people – Howard as one of the nicest athletes, Coyle as a colleague at the Tour de France who has done epic work exposing cheating in cycling. Howard recalls how he was taken in – for free – by Tim Mulqueen, Coach Mulch, a goalkeeper mentor in New Jersey: “He hammered ten in a row, so fast it was hard to get back on my feet between them. The moment I saved one, another was already whizzing past me. “'Recover faster,’ he barked. ‘You can do better than that.’” Coach Mulch also trained Howard to throw the ball rather than punt it, even in the closing desperate minutes. That way you have control. Fast forward to the 91st minute against Algeria in South Africa in 2010, when Howard started a full-field attack that kept the USA in the World Cup. The pass dated to New Jersey, two decades earlier. Howard could have sulked when Manchester United brought in Edwin van de Sar. Instead, Howard studied how van de Sar threw his long body to the ground, cradling the ball. Tim Howard imitated the man who had taken his job. The Howard book arrived over the transom from HarperCollins and the Coyle book was recommended by two disparate friends, a classical musician and a second-career keeper coach, who live 9,000 miles apart. Neither knew that Daniel Coyle is a friend of mine. The cellist and coach were both impressed by Coyle’s scientific description of how the human system learns the lessons of repetition, through a material called myelin. “(1) Every human movement, thought, or feeling is a precisely timed electric signal traveling through a chain of neurons – a circuit of nerve fibers. (2) Myelin is the insulation that wraps these nerve fibers and increases signal strength, speed, and accuracy. (3) The more we fire a particular circuit, the more myelin optimizes that circuit, and the stronger, faster, and more fluent our movements and thoughts become.” All the rest is practice. Gym rats. Musicians improvising with purpose. Teachers imposing order. Coyle has a great segment on a charter school (KIPP) in Houston. Students doing their reps, like Tim Howard diving for a save, over and over again, building up his myelin. When I was in grade school, whenever I had spare time, I would take out “Richard Halliburton’s Book of Marvels,” about his adventures around the world.

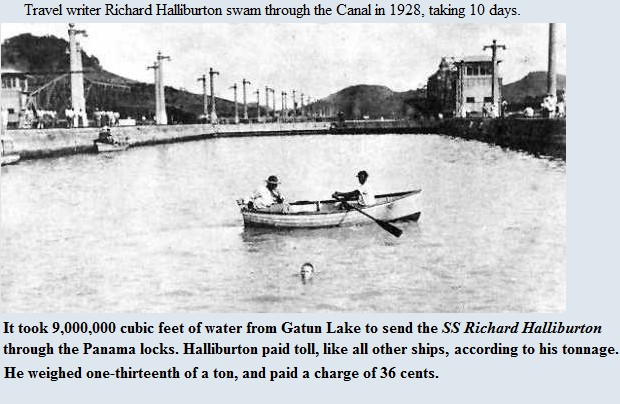

Halliburton was a daredevil writer who once swam the Panama Canal – took him 10 days – and paid the toll -- 36 cents. He jumped 70 feet from the Sacrificial Altar for brides in Chichen Itza, Yucatán. He rode an elephant, just like Hannibal, across St. Bernard’s Pass in Switzerland. His writing was more than about his stunts. He loved cities, expressing awe at the bridge spanning the Golden Gate, raving about the skyscrapers of New York City, describing the border between Europe and Asia -- Istanbul. He gave me wanderlust. I sat in the classroom in leafy Queens and dreamed about all those places, hardly as an adventurer but maybe a grade up from tourist – a journalist who could drop the surging tide at Mount St. Michel or the graffiti at Pompeii into his work. Halliburton’s life was hectic, and short. In March of 1939, he and his companion, Paul Mooney, tried to sail a Chinese junk from Singapore to the Golden Gate, and were never heard from again. (I have always thought it bizarre that two of the writers who touched me the most, Halliburton and Thomas Wolfe from Asheville, N.C., died months before I was born.) The other day I discovered that Halliburton also made a movie in 1933, called “India Speaks,” a cross between a documentary and a drama. (The drama part was filmed in Griffith Park, Los Angeles.) It sounds a little hokey in the New York Times review of 1933, but because my wife has been to India more than a dozen times and we love the culture, I was eager to find a copy, somewhere. I toggled around on the Web and discovered on the IMDb site these saddest of words: “This film is believed lost. Please check your attic.” Got a lot of National Geographics in the attic, but no old movies. I do have a faded copy of “Book of Marvels: The Occident” on my shelf of honor with James Joyce and Wolfe. The final chapter is about Istanbul, the water and the minarets. We finally got there a few years ago, one of the great cities in the world, and I thought about Richard Halliburton. Wish I had his movie. Ray Robinson isn’t sure if Lauren Bacall called him a cheap bastard or cheap SOB. In fact, she may have called him both.

That was in 1941, when they were thrown together for a few hours in Sardi’s, with Robinson unaware that he and his pal had become the de facto hosts of an impromptu party. Robinson, now 93, has survived the vilification by the gorgeous and opinionated young woman to become a magazine editor and author of many books, including celebrated biographies of Lou Gehrig and Christy Mathewson, as well as a charming little book entitled Famous Last Words, which is just what the title says. Bacall’s words became famous to Ray Robinson. She was 17, an aspiring actress and model from the West Side then known as Betty Perske; he was just graduating from Columbia. His pal Ed Gottlieb knew the young woman, and the three of them were out together, and she suggested they drop into Sardi’s. Some of her friends came over, and drinks were ordered, with Ms. Perske assuming her two gallant squires were good for it. Robinson and Gottlieb did what any two broke young men would do. They simultaneously headed for the men’s room to discuss how they were going to pay the tab. “Ten bucks or so,” Robinson recalls. “That was a lot of money in those days.” To avoid washing dishes, their stratagem was to ask Ms. Perske to sign an IOU to Sardi’s since (a) she was gorgeous, and (b) she knew somebody in the Sardi family. When they apprised her of the situation, she let loose some vocabulary that presumably Humphrey Bogart and Hollywood directors and critics would later hear. But she did sign something and they were free to go. “We got outside and she said, ‘All right, who’s going to call me a cab so I can get home?’ We said, well, if we couldn’t afford the bill at Sardi’s, how could we afford a taxi?” It was then that Ms. Perske uttered sneering last words to Robinson: “I should have known better than to go out with a couple of blankety-blank college students.” “She just walked away into the night,” Robinson recalled. He did see her again in 1945 when she was the bombshell star of her first movie, “To Have and Have Not.” He and Gottlieb were back home from the military and put on their uniforms and talked their way into a press party at the Gotham Hotel. (Robinson remembers stuff like that.) She greeted Gottlieb, whom she had dated, and moved on, politely. Robinson has been telling the story ever since, as one of my very favorite lunch companions, discussing baseball or books or politics. He and his lovely wife Phyllis, a longtime editor at the Book-of-the-Month Club, have been living near Gracie Mansion while Bacall nested in the Dakota, until her passing last week at 89. Given the twin nationhood of East Side and West Side, he and Bacall never met again. Sometimes a person is revealed in the chords as well as the relationships.

There was a memorial for Joe McGinniss in New York on Friday, two months after he passed at the age of 71. Friends and family told their stories, revealing a man of vastly eclectic interests and ties. Roger Ailes, the brains behind Fox, told of a warm friendship that went back to 1968, when McGinniss, a kid of 26, wrote “The Selling of the President.” They did not fight over politics, Ailes said. They just enjoyed each other’s company. Others of the liberal persuasion told how McGinniss could write about Ted Kennedy or Sarah Palin with equal tenacity. And Ray Hudson, the garrulous English soccer broadcaster, who does La Liga of Spain, popped in from south Florida to talk about his friend, who maintained he was actually Italian despite a name and a face that insisted he was surely not. The four McGinniss children were very sweet with their memories and emotions. And one of the best stories came from Joe’s lawyer, Dennis Holohan, who told of not being able to even speak of his military service in Vietnam for 20 years afterward. McGinniss had been one of the great American journalists like David Halberstam and Gloria Emerson and Mike McGrady who went there and exposed the mission for the tragic fraud it was. Finally, Joe cajoled Holohan into joining Joe on a trip to modern Vietnam. They took different routes from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City/Saigon, and the lawyer arrived first, taking a taxi tour of a war museum and then a Buddhist temple, where he totally lost it. Meltdown. But his driver consoled him, saying the Vietnamese people had moved on. You’re a good man, Minh said. I can tell. You need to get past it. When McGinniss caught up with Holohan in Saigon, the lawyer told his friend what had happened at the temple with the taxi driver. McGinniss said he knew it would happen. That was why he proposed the trip. The friend is still stunned that his friend could anticipate such a breakthrough. I never met Joe McGinniss but we became email pals two decades ago, united by our love of Italian calcio and Roberto Baggio and the language and the daily pace of Italian life. I am never jealous of other people’s talent or success or dedication or great ideas but I was tanto geloso of the time he spent in a hill town, and the book he wrote about a scandal among minor-league players he knew. I got to know Joe McGinniss better from the music his family selected for the memorial:

And at the end, there was a slide show of Joe McGinniss’ life, frolicking with his children, out and about in the world, thoroughly engaged, enjoying himself immensely. The background music was:

That’s how I got to know somebody I never met. Addio, buon amico. The best news is that Eight World Cups: My Journey Through the Beauty and Dark Side of Soccer has been chosen one of the top non-fiction books of May by Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/b/ref=s9_dnav_bw_BoNF_b?_encoding=UTF8&node=4919321011&pf_rd_m=ATVPDKIKX0DER&pf_rd_s=merchandised-search-4&pf_rd_r=1T1PXY4FHWCZ2E4AA4S2&pf_rd_t=101&pf_rd_p=1800977162&pf_rd_i=390919011 The publication date is May 13. The e-book version will also be released that day. There will be an excerpt in a major publication very soon. I will be making appearances at book stores in the East, starting May 29, in Huntington, Long Island, at the terrific Book Revue. Please consult this list, to be updated regularly: http://www.georgevecsey.com/book-appearances-2014.html The reception has been lovely, particularly from soccer lifers. “George Vecsey gets it,” one review began: http://internationalsoccernetwork.com/blog/?tag=george-vecsey I will also be visiting ESPN soon to talk about my book. No schedule yet. I sat in on a conference by ESPN in New York the other day and was enthused to hear about the documentaries and game coverage in the works. It was great to catch up with John Skipper, Bob Ley, Julie Foudy, Alexi Lalas. Taylor Twellman and Jeremy Schaap and pick up on the planning and enthusiasm of this soccer-friendly network. Finally, I plan to write occasionally for my own site in between appearances. Your input about the World Cup will be more than welcome. Who will make the final cut for the U.S. squad? Who will win the World Cup? Plenty of time to talk about that. Best, GV. Joe McGinniss, who died on Monday at 71, wrote about politics and scandal and hypocrisy. In his foray into Italian soccer, he found himself at that very same intersection.

In his 1999 book, “The Miracle of Castel di Sangro,” he was living in a small hill city in the Abruzzo, getting to know the players. Then he watched them blunder away a final game that allowed the team from nearby Bari to advance into Serie A. Soon he accused some of the players of throwing the game, comparing them to the Red Brigade of the ‘70’s. “Tu non sei costretto a parlare,” one key player said. You don’t have to speak. This was revolutionary stuff in 1999. Seven years later, the world discovered that major teams in Serie A were leaning on referees and some players were gambling on their sport. Joe was not surprised. By that time, he was back in Massa-chusetts. The beautiful game was much like the rest of life. We had one thing in common – awe of Roberto Baggio, the wispy pigtailed Buddhist genius, who created beautiful moments, from nothing. “Other than my sons, he's the only man I've ever truly loved,” McGinniss wrote in an e-mail. We never met. I remember seeing a very young sportswriter with a lean and hungry look, working for the Bulletin (“In Philadelphia nearly everybody reads the Bulletin.” But not anymore, inasmuch as that paper is long defunct.) He soon wrote “The Selling of the President,” about the Nixon campaign of 1968, and later “Fatal Vision,” about the conviction of an army doctor for killing his pregnant wife and two children. Janet Malcolm and others have accused McGinniss of misleading the doctor by professing to believe him to keep his access. I have never fully understood that. As a reporter, I have sat and listened to politicians, business people, sports officials, religious leaders and entertainers tell me all kinds of stupidità, and usually I kept a straight face, The trick is to keep them talking. McGinniss and I never discussed that, or his time in Alaska, living next door to the Palins. I was jealous that he had lived in the Abruzzo. I’ve got dozens of his e-mails, deploring the gun culture in America or bad soccer on the tube, but he never bemoaned his wretched medical luck – inoperable prostate cancer, 14 months ago. “Welcome to the Hotel Carcinoma," he wrote last year. He could not hang in there for the World Cup – Pirlo and Buffon and Balotelli in Brazil. I would have loved to hear his critiques. Buon lavoro. Buona vita. Riposate in pace. Bruce Logan served two tours in Vietnam as an officer, and counted himself lucky when he returned to the United States. Now he and his Canadian wife, Elaine Head, consider Vietnam a second home.

Some Americans go back to confront their bad dreams in the cities and countryside. They are often touched by the conciliatory tone of word and deed. In a village outside Hanoi, Logan and Head were invited to a feast at the home of a woman named Phuong. In a matter-of-fact way, she described President Nixon’s Christmas bombing of 1972, the bodies and the rubble. The former officer expressed his sorrow for the carnage. “In response, Phoung turned her misted eyes to mine, laid her hand on my forearm and said, ‘I am so glad that you did not die in the war and that we are here to have dinner together in my house.’ “At that, everyone had a silent cry, for long ago pain, for the moment we had shared, and for the gift of forgiveness in Hanoi.” Logan and Head tell many stories like this in their book, Back to Vietnam: Tours of the Heart, published by JOTH Press, Salt Spring Island, B.C. and First Choice Press of Victoria, B.C. My wife and I had similar experiences in 1991 when we were visiting Vietnam as part of her child-care work. People casually divulged details of the war – but only if we asked. Mostly they demonstrated reconciliation, north with south, Vietnamese with Americans. Not everybody goes back. I have friends who lived through terrible times in Vietnam and do not care to go back. I was never there in wartime; I understand. I had a nice visit with Sen. John McCain once, and asked why he and his buddies help send goods to Vietnam. He shrugged, quite modestly, suggesting it was the right thing to do. I think about that when I see him on television. There is a good man in there. Like many combat veterans, Bruce Logan kept the war inside him, but he and his second wife, Elaine Head, visited Vietnam in 2006 with a group of veterans and their families. The book has touching stories of finding old foxholes, places where soldiers and civilians died, where horrible memories live, tempered by the forgiveness of the Vietnamese, that sometimes feels like a miracle. The glorious byproduct of the visits was gaining a family. In the World Heritage town of Hoi An, just outside Da Nang, Logan and Head met Le Nguyen Binh and his wife Quyen, who operate Reaching Out, a distributor of hand-crafted goods made by people who might be consider disabled. My wife and I have purchased some of their high-quality goods. (I wrote about Binh and Quyen in a previous post.) Binh and Quyen have made a standing offer for Logan and Head to live in Hoi An, and be cared for in their old age, perhaps even be cremated there. Not yet, Logan and Head say, politely. They still conduct tours for Americans who need to return to Vietnam. Their sweet book is graced by their anecdotes, their adventures, their bond with their other home. I was in awe of Sam Toperoff days into my freshman year at Hofstra College. From my workship with the athletic department, I knew he was a transfer basketball player, out of the service, waiting to play the following season.

Then he turned up in a sociology class, and he stood out. He was 5-6 years older than me and knew how to talk in class. I still remember Professor Nelson explaining the sociological concept of brothers and others – the circles of life, people we care about, people we don’t necessarily care about. “You, Toperoff, are my brother,” Professor Nelson said, “and the rest are others.” A hundred people in this huge lecture hall, and the professor knew Sam’s name. Toperoff started for a couple of seasons of varsity ball. My strongest memory of him is singing – maybe a Belafonte song? – in the locker room before a road game, nervous energy, channeled into song. He was a force. Stephen Dunn, the shooting guard, now a Pulitzer-Prize-winning poet, tells about listening to Sam and another teammate in a hotel room, talking about Moby Dick. Imagine. Not women or zone defenses, but words, concepts. (That was quite a team -- a novelist and a poet, starting.) Sam taught at Hofstra for 20 years and has written 13 books on extremely varied subjects, including the gripping Pilgrim of the Sun and Stars, about a Basque peasant who makes a pilgrimage to the Vatican. Sam also wrote sports for magazines and for 15 years worked for public television, most notably a travelogue series. My wife bought all of them. Now Sam lives in the French Alps (in a house he built) with his wife and daughter and grandson. He is a hero to his pals because he has continued to write. Lillian & Dash, his novel about the long affair between Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett, is being published by Other Press in July of 2013. Sam has gotten good advance attention, including a Kirkus review. The novel is available via Amazon and other sources. I've read it, and I love the dialogue and insight into two talented people from another time and place. It’s been a lot of decades; Toperoff still scores. I’ll be talking about my book, Stan Musial: An American Life, on Saturday, Nov. 10, in Harrisburg, Pa.

The talk will also be streaming live at 3 pm at: http://pcntv.com/ The talk is part of the Harrisburg Book Festival, Friday through Sunday, at the terrific Midtown Scholar Bookstore-Café, 1302 N. Third Street in Harrisburg. Tel: 717-236-1680. My appearance has been arranged through my daughter Corinna Vecsey Wilson, vice president of programming and host at PCN. The book was a New York Times best-seller in 2011. For a couple of glimpses of Musial, please see: http://old.post-gazette.com/pg/11191/1159123-148-0.stm http://6thfloor.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/06/the-story-of-stan-the-man/ Musial will turn 92 on Nov. 21, and is the icon of St. Louis. I will be linking his modest, hard-working persona to his Pennsylvania roots in Donora in the western part of the state. Stan the Man was one of the great baseball players of his time, or any time. At first I thought the subtitle should be The Forgotten Man (reference to the song in High Society) but when I began researching his roots as an immigrant's son in zinc-and-steel-and-smog country, I realized the subtitle An American Life was much better. It is always an honor to talk about one of the sporting heroes of my childhood. |

Categories

All

|