|

Who thinks about Casey Stengel these days?

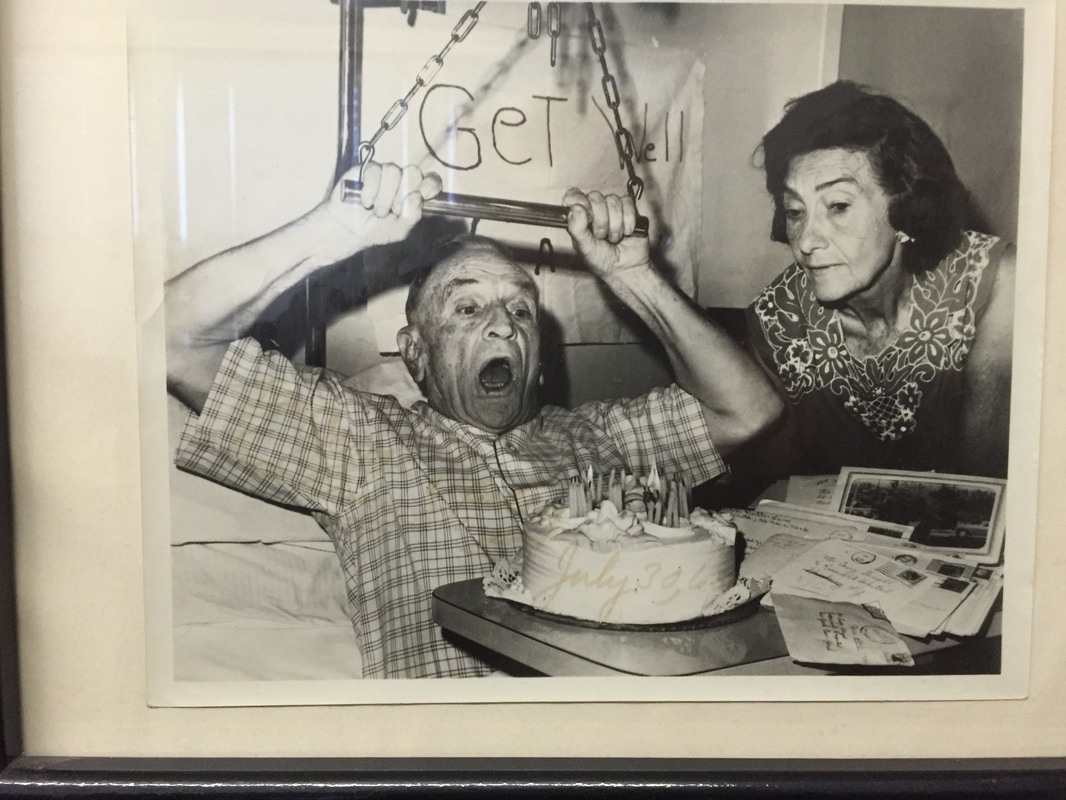

Mets fans should, because he basically invented the Amazin's. Just the other day, a hit rolled into the right-field bullpen and a Braves outfielder flung aside a garbage pail to retrieve the ball -- a garbage pail! -- and I recalled what the Old Man used to say: "Every day in this game of baseball, you see something you never saw before." Still I might have thought history contains all it needs about Stengel, the quintessential figure on all four New York teams – “the Brooklyns,” the Giants, the Yankees, and the Amazing Mets. Casey let a sparrow fly out from his doffed cap as a Dodger; he hit an inside-the-park homer for the Giants in the World Series; he won 10 pennants in 12 years as the Yankee manager; and he managed the Mets for their first four seasons. Now, my friend Marty Appel has found good new stuff about Casey – and his times – in a new book, “Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character,” to be published by Doubleday on March 28, just in time for a new season. Appel uncovered some gems about Casey’s childhood in 19th Century Kansas City and his playing career in a Brooklyn so long ago there were no hipsters. He has used computerized libraries and files not available to previous biographers of Stengel, including the late Bob Creamer, a luncheon companion of ours. For example: Appel discovered that the Stengel family lived in the same neighborhood as Charles (Kid) Nichols, a Hall of Fame pitcher who won 361 games from 1890 to 1906. When “Dutch” Stengel was a rambunctious teen-age ball player, the old pitcher advised him to always listen to his managers. “Never say, ‘I won’t do that.,'" Kid Nichols said. "Always listen to him. If you’re not going to do it, don’t tell him so. Let it go in one ear, then let it roll around there for a month, and if it isn’t any good, let it go out the other ear.” This is wonderful advice. I spent a lot of time around Casey from 1962 to 1965 -- in his office and late at night in bars – and I never heard him mention Kid Nichols. But I now know that Kid Nichols helped Casey learn as a player – and teach as a manager. Appel tells a great story (new to me) about a prospect named Mantle, who could run but was slowed down by his habit of looking at the ground. Stengel told Mantle he was no longer playing football in Commerce, Okla., that the major leagues had groundskeepers who created smooth base paths and that he should keep his eye on the ball and the fielders. It made Casey crazy to see blank looks on players. The Old Man also tried to teach “my writers,” in murky soliloquys very late at night. Just when you were about to give up (or doze off) he would grab you with a stubborn paw and say, “Look, you asshole, I’m trying to tell you something.” Appel has learned about Casey’s wife, Edna Lawson Stengel through an unpublished memoir made available by Edna’s niece, Toni Mollett Harsh. Apparently, the Stengels considered themselves too old – in their thirties – to start a family, but they were affectionate toward the wives and children of some of the younger players. (He bought a ginger ale for my oldest child, Laura, in the motel bar in Florida after his managing days. She remembers it vividly.) I learned something else. Appel amends the legend that Stengel’s wealth came through his wife’s family, which owned a bank and businesses in Glendale, Calif. In fact, young Casey paid attention to a teammate from Texas who talked him into buying oil rigs. Casey often barked, “You make your own luck.” Marty Appel reminds us all that Casey Stengel made his own luck.

WALTER THOMPSON

5/19/2017 11:23:46 am

I'm reading the book now. It's a great history about the old NY teams. And hilarious as well. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|