|

Say what you will about the I-Man, this alternately cruel and shy character who passed Friday at 79, he kept me alive many years ago.

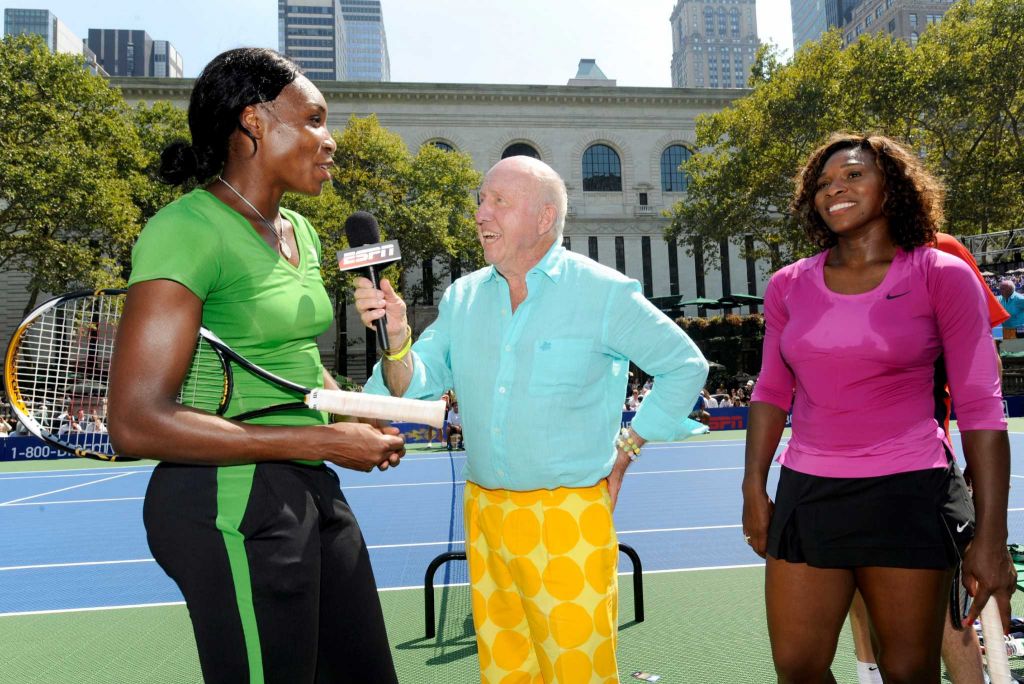

I had paid him no attention until he popped up on the new sports talk station, WFAN -- 660 on the AM dial – in the late 80’s. Most of the station was devoted to hard-core sports babble but his four hours in the morning – “the revenue-producing portion of the day,” I think he called it – was a snarling, sneering refutation of sports, plus music critiques and skits. One of the best things I have ever heard on the radio was a skit in which Princess Diana visits America to get away from that strange bunch she had married into. (I forget the name of the woman who portrayed Diana.) Somehow or other, Diana is invited to Imus’ home in Connecticut, for a hot-dog roast with real people, that is to say, the I-Man. She is so enthralled by his informality that she pleads for asylum, asking in a plaintive voice, “Please, may I stay here?” Oh, if only she had. Imus grew on me, with his frequent praise for his favorite musician, Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys. He also acted as a one-man media critic of the noble knights of the keyboard back when newspapers and sports sections and columnists played to the snarky taste of the New York region. He was vicious toward his station mates, calling Mike Francesa and Chris Russo “Fatso and Fruit Loops.” He derided his literary agent and consigliere, Esther Newberg, referring to her as, of course, “Lobsters.” He regularly berated the plugged-in sports columnist of the Daily News, Mike Lupica, and sometimes when he had nothing else to do, he picked on me. (Let it be noted that Lupica and I are clients of the sainted Ms. Newberg.) One time Imus relayed a new item about an elderly gent who was left, in a wheelchair, I believe, by his guardian at some rural dog track. This became the Imus standard for irrelevancy, for being past it. He often would ridicule my masterpieces and state the obvious: “Dog-track time for Vecsey.” One time my sister Janet rang up the station to blast the I-Man and he put her on the air, and was oh, so civil to her. That was the I-Man, a human mood swing. I met him a few times, hanging out in a baseball press box, making no fuss. In person, the radio tough guy would softly say hello and kind of look sideways at me. How did Imus save my life? My wife was on a trip somewhere and I thought it made sense for me to drive our car from south Florida to Long Island – straight through, overnight (with a couple of 15-minute naps at rest stops.) I got near Baltimore, the sun rising, and to keep awake I punched the dial seeking Imus going on the air at 6 AM. But I was sleepy. Very sleepy. I could feel the car starting to edge onto the rough border of the inside lane. I righted the steering wheel and willed myself to stay awake. But I was sleepy. Just then, Imus began a tirade against a failing columnist who had just written another piece of foolscap. In his basso voice of denunciation and doom, Imus pronounced: “Dog-track time for Vecsey.” That got my adrenaline surging – who doesn’t like attention? – and I gripped the wheel and listened to Imus for the next four hours until the revenue-producing part of the day was over, and I got home, alive. * * * I’d like to say that my debt to the I-Man made me a listener for life, but that’s not true. He and his radio sidekicks increased their racial crap and their creepy comments about women until one day he made ugly comments about the mostly-black players on the Rutgers women’s basketball team, competing in the Final Four. That was it. I turned Imus off, and never listened to him again. In a way, Imus was a predictor of where we are today. However, unlike some public figures I could name, he appeared to be generous, to have a heart. According to the obituaries, the I-Man hosted young people at his Imus Ranch and raised funds for Iraq veterans, and his wife Deirdre has her own charity at a New Jersey hospital. It seems he affected thousands of lives – plus one sleepy driver, edging off the Interstate on a warm sunrise. * * * Here’s a treat: the NYT’s star, Robert McFadden, on the I-Man: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/27/arts/don-imus-dead.html I was busy working on something else when I heard about Alvin Jackson Monday, so I kept going, with a heavy heart. Then I received emails from three pals, one an old ball player from Brooklyn saying, “From what I know, he was a class guy,” and one e-friend from West Virginia saying, “He sounds like a fine fellow,” and one pal at the Times, saying “I’m sure you knew him.”

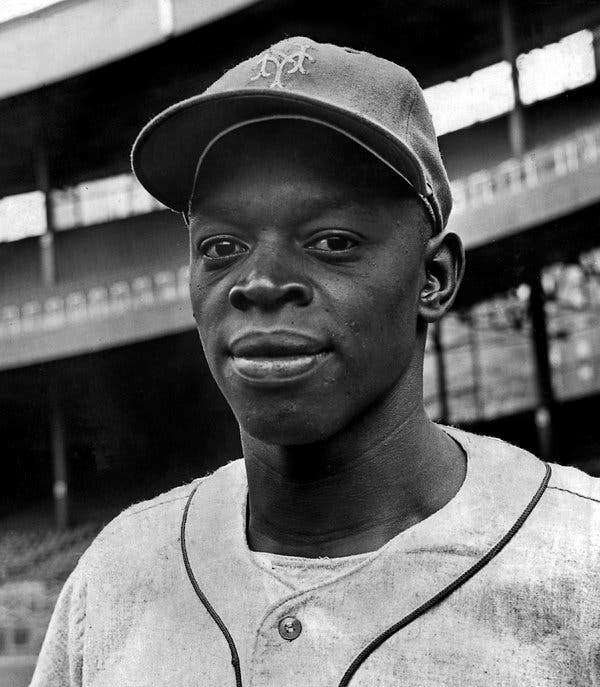

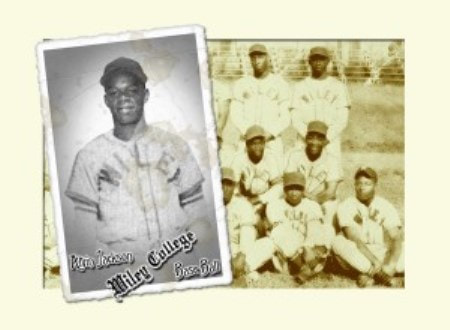

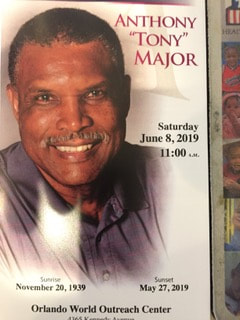

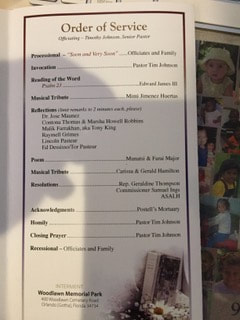

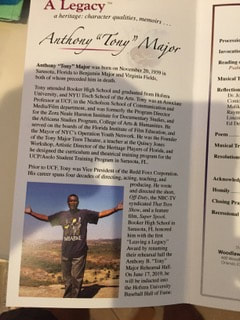

Yes, I knew Alvin Jackson from April of 1962, knew him from games he won and games he lost, and I also knew him as a wide receiver in touch football. True. You can read the lovely obit in the Times and learn a lot of the details of his life: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/sports/baseball/al-jackson-dead.html I was a young sportswriter in 1962, first year I traveled. Jackson was a steady pitcher on a team that lost 120 of 160 games. Casey liked him for himself and also because Casey, who was childless, was proud of the Mets' considerable number of "university men," many of them pitchers. By Casey's standards, Jackson was a university man, but Jackson could also keep the ball low and he never lost his poise. When we interviewed Alvin after losses, he kept it inside, which I attributed it to the caution of a black man from Waco, Tex., who has learned not to show too much of himself. He also had occasional whooping laugh that he allowed to escape. We never got serious about much, but on Aug. 28, 1963, I watched Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech from the Mall in Washington, on the TV in my hotel room in Pittsburgh, and when I went down to catch the team bus to the ball park, I got into a conversation with Alvin and Jesse Gonder, the catcher, and Maury Allen of the (good old) New York Post. We agreed that something momentous had happened that day and I felt we all had gotten a glimpse of the others’ heart. https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/the-day-i-watched-dr-king-and-the-mets Alvin was living on Long Island in the off-season, and one of my colleagues at Newsday mentioned that we played touch football once or twice a week at a park in Hempstead. Jackson and most players had the same economic level as reporters, so sometimes he worked at a winter job, but most game days he showed up, ready for a run, ready to break a sweat. In 1963, another Met, Larry Bearnarth, who was living nearby, joined the game. They got their tension during the season. What they wanted was a workout. They never big-timed us, tried to call plays or ask for the ball. Joe Donnelly, who had a great arm, and I, who had no arm at all, were usually the quarterbacks. Let me say, it was a trip to be in a mini-huddle, calling a play involving somebody who pitched in the major leagues. I think Alvin and Larry were in the game on Nov. 22, 1963, when the fiancée of one of the players came running across the parking lot and delivered the terrible news. We all just went home. By 1964 Alvin was a club elder: "Wonderful gentleman," Bill Wakefield, a very useful pitcher on that squad, wrote to me in an e-mail. "He was very nice to me. Treated me (a rookie) like I was a veteran of the original Mets vintage. Great smile and laugh! Good pitcher. Not overpowering stuff, but knew how to pitch. Good guy." Jackson pitched one of the most masterful games of that first Mets era on the final Friday of the season, in St. Louis: He shut out the Cardinals, who were fighting for the pennant, by a 1-0 score, bringing the chill of winter into the city, but the Cardinals survived on the final day. https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B10020SLN1964.htm As Alvin’s career dwindled, he moved on, and then he was a pitching instructor for various organizations, including the Mets in later years. When we ran into each other, he was cordial; not all ball players remember your face. Once in a while, I would see him and make the motion of a quarterback throwing long, and he would give his whooping laugh, not needing to add, “as if you could.” He stayed on Long Island a long time. I never knew that his wife, Nadine, a lovely presence, was the chairwoman of a business department in a Suffolk high school. I just knew they were a dignified couple -- a university man and woman. Alvin Jackson brought dignity and discipline that rubbed off on teammates, on reporters in the locker room, and even on fans who could tell, from a distance, that he was indeed a very nice guy.  Tony and Sid: Just Like the Old Days Tony and Sid: Just Like the Old Days Only a few months ago, Tony Major was playing 3-on-3 basketball in an over-75 tournament. He could get off his feet, could pop jump shots from the corner. Sent videos back north so his friends could see. He was an athlete and an actor and now a teacher and documentarian at the University of Central Florida, working on a film about Trayvon Martin. He was looking forward to June 17, when he would rejoin some old baseball teammates from Hofstra, when their 1960 team will be inaugurated into the school’s athletic Hall of Fame. Instead, Tony passed suddenly on May 27, at 79. We just heard about it, and a lot of us who knew him back in the day are gutted by this news. Tony made a quickie visit to campus last October, after half a century. He spent part of the day with old jock friends, another part getting a tour of the new communications building from two nice officials and also visiting the playhouse where he had learned to speak Shakespearean. We were all invigorated by his youthful presence. At lunch, he told us about his life. We knew him as somebody who played three sports, but he felt Hofstra was not ready for a black quarterback and he was not big enough to star in basketball. He was a useful member of the 1960 baseball team that won the grand old Met Conference but could not play in the NCAA tournament because of exams. A son of Florida, he had commuted every day to Long Island from Harlem where his mother now lived. He told us about how he gravitated to the great drama department, had tried out for roles in the annual Shakespeare Festival. Laughing at the memory, he described how a black man from the South had learned to shape his speech into the cadence and pronunciations of Shakespearean English. But he did it. And he kept acting, in the city at first. Later, he graduated from New York University Tisch School of The Arts and also taught film production and producing at NYU for two semesters. His baseball ability and knowledge got him a minor role as the backup catcher in the 1973 movie “Bang the Drum Slowly.” He saw young Robert De Niro playing a dying catcher, crouching behind the batter, extending his hands too far. Tony told us how he had passed along some tips about not getting fingers broken by the bat or a foul tip. He moved to Hollywood, playing some bit parts, but also learning about television production. One year he worked with the Dolly Parton show – and raved to me about her intelligence and kindness. And then he moved to Florida, where the university was expanding in Orlando. He began making documentaries, often with an African-American theme. He married late, a woman from Africa, and they had two children, both still in school. “That’s why I’m still working,” he said, laughing. He had so much going on, and now he was reconnecting with some old teammates, plus me, a student publicist who sometimes traveled with the baseball team. Tony had a gentle soul, did not hide the sting of stereotypes. He felt he was used as a pinch-runner in baseball when he could have played more. He recalled road trips to the Mason-Dixon Line, circa 1960, when black players were restricted in the team hotel. And after that, he created a joyous persona, a productive life and career. Early this year, Tony sent me some photos and videos of the over-75 basketball tournament in Florida. There he was, off his feet, getting a rebound, putting it back in. And there he was guarding Sid Holtzer, a former Hofstra basketball player, also still in good shape. In one staged photo, Tony was waving his hand in Sid’s face. Sid never liked that, Tony said. Still didn’t. He giggled at his own mischief. We were looking forward to his next trip north, on the 17th. Instead, there was a funeral on June 8 in Orlando. If there is any lesson to this, it is: reconnect with old friends sooner, and treasure them. * * * Note: Sid Holtzer, another athlete and friend from Hofstra, attended the service and thoughtfully sent photos from the program. (From the University of Central Florida:) https://www.ucf.edu/news/longtime-professor-tony-major-remembered-for-contribution-to-film-ucf/ http://www.nicholsonstudentmedia.com/news/he-brought-hollywood-and-filmmaking-to-orlando-and-ucf-faculty/article_762c9ad0-86c1-11e9-9af6-9b3c9e59c4c9.html Birch Bayh called me at the Times about a decade ago. I was curious why a former US senator wanted to talk to a sports columnist, and of course I called him back.

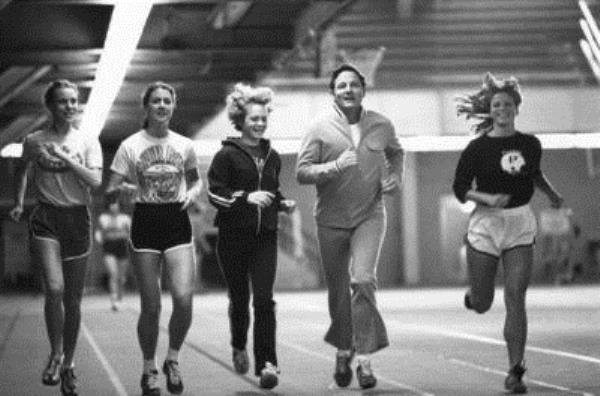

Now I can’t remember the reason he called. His obituaries this week praise him as a major force on Title IX, which has enriched sports for women – for everybody – in America, but I don’t recall him presenting himself as the Title IX guy. Whatever it was about, we schmoozed for a bit. I told him I had covered his re-election in 1970 and I determined that this son of Indiana was now living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. As long as we were chatting, I had a question for him. It went something like: “Senator, could I ask you a question about politics? I’m looking at all this Tea Party business, and it seems that some of the new members of Congress hate government, can’t even stand being in Washington, just want to shut things down.” He was diplomatic, did not go fire-and-brimstone on me. After all, he was known as a very moderate Democrat; he had to be, to win in Indiana. But he allowed that he had never seen anything like the antipathy between Democrats and the new Republicans, wandering around brandishing mental pitchforks. He recalled with a tinge of sadness that he always had friends across the aisle. That made me think about legendary friendships between Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch, Lyndon Johnson and Everett Dirksen, Dick Durbin and John McCain (once again being vilified by Donald Trump.) On the phone, Birch Bayh sounded reflective, maybe even sad, recalling better political times, and then we said goodbye. But his brief comments fueled my sense that things were not as mean in the 1970s when I had a brief fling as a national correspondent. There were giants in those days, on both sides of the aisle. I keep a mental list of Republicans I met, or covered, and admired, mostly from Appalachia and the border states I covered: I covered the retirement announcement of Sen. John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, a thoughtful gentleman. (One of his aides back then was a young guy named Mitch McConnell, whom I consider one of the most empty and destructive people I have ever seen in public life.) I ran around Tennessee one glorious September afternoon in 1972, covering the re-election campaign of Sen. Howard Baker, who was accompanied by his assistant, Fred Thompson. They were good company, rational people, and Baker became a giant during the Watergate proceedings. When I lived in Louisville, Richard Lugar was a constructive Republican mayor of Indianapolis, just to the north on I-65; later he became a highly positive Senator. Later, I observed Rep. Tom Davis of Virginia, the chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, during the baseball steroids hearings -- a thorough gentleman who later got sick of the nasty politics and retired. In that same period, I spent an hour in the office of Sen. John McCain, during a hearing on Olympic reform, and I retain a strong impression of him as an American hero, despite Donald Trump’s blather – with no retort from Trump’s new best friend, Lindsey Graham. How far we have fallen. * * * Two farewells to Sen. Birch Bayh: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/14/obituaries/birch-bayh-dead.html https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/14/opinion/birch-bayh-constitution.html Two daughters who adored their fathers.

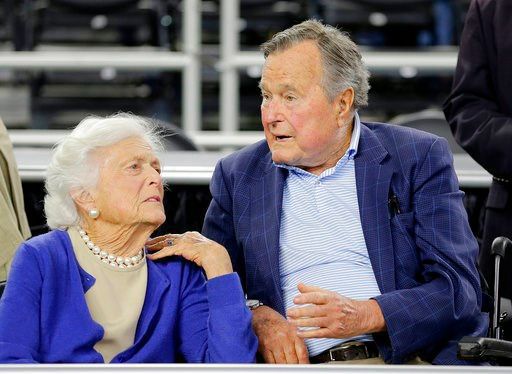

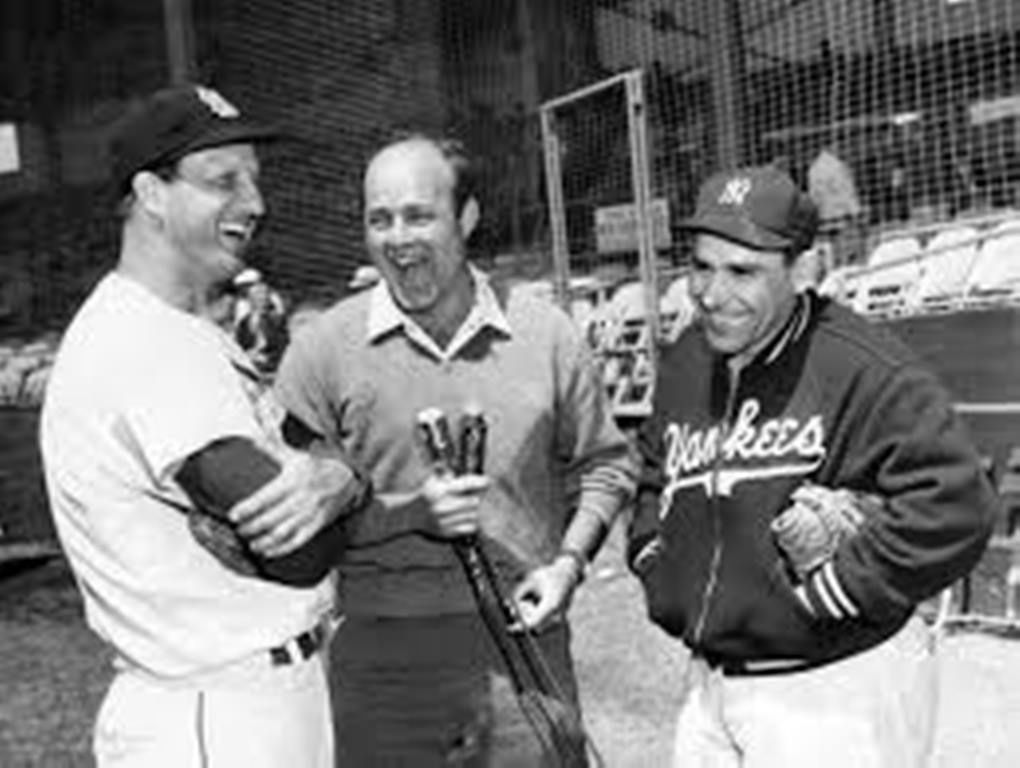

Julia Ruth Stevens died Saturday at 102. She was the adopted daughter of Babe Ruth and, as long as she lived, referred to him as “Daddy,” as Richard Goldstein notes in his masterful obituary. Dan Jenkins, one of greatest sportswriters, died Thursday at 90. He was eulogized by many admirers in his business, the best coming from, of course, his daughter, Sally Jenkins, sports columnist at the Washington Post. Sally, terrific writer that she is, described the hectic and eccentric life of a sports columnist who was usually at a golf tournament or football game when the family gathered for Thanksgiving and other holidays. . Her dad was as glib about the indignities of old age as he was about golfers who mis-read the terrain of the course. Sally tells about her dad wheeling himself down the hallway of the hospital heading toward a presumed quadruple heart bypass. When he emerged, he was told he had needed only a triple. "I birdied the bypass," he pronounced. That’s it. I’m not going to try to duplicate the Jenkins family, father or daughter. Read Sally’s tribute to her dad. The Washington Post has a pretty strong paywall, bless its heart, but you might be able to read it there, or the Chicago Tribune. Or pay for it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/ https://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/ct-spt-sally-jenkins-remembers-father-dan-jenkins-20190309-story.html Plus, Bruce Weber’s excellent obit in the NYT: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/08/obituaries/dan-jenkins-dead.html Babe Ruth’s daughter also receives a brilliant tribute in the Monday NYT. She was the daughter of Babe’s wife, Clare Hodgson, and was adopted and treated royally, as a daughter by the gregarious, larger-than-life Babe. No doubt she witnessed, and heard about, examples of Babe’s excesses, even after he stopped playing. As subtle as a diplomat, she discussed “Daddy” as she saw him – a man who made egg-and-salami sandwiches and took her golfing out in Queens. And when she started dating, he insisted she be home by midnight. Imagine: The Babe. Enforcing a curfew. They lived on the Upper West Side, in a 14-room apartment; whenever I am in that neighborhood I envision The Babe, with a cap on his head, walking on Riverside Drive or thereabouts, just another West Side burgher. She was an ambassador not only for “Daddy” but for baseball itself, waving to adoring crowds at the closing of “The House That Ruth Built,” waving to adoring crowds at Fenway Park, where The Babe first pitched shutouts and hit home runs. When my alma mater, Hofstra University, held an academic conference on The Babe in 1995, she and her son, Tom Stevens, represented the Babe and gave out Babe Ruth bats to a few lucky people, including me. https://lwww.nytimes.com/1995/05/01/sports/sports-of-the-times-the-babe-redbirds-and-a-sunday-game.html But that’s enough from me. Better you should read Richard Goldstein’s obituary of Mrs. Stevens: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/09/obituaries/julia-ruth-stevens-dead-babe-ruth.html We were watching MSNBC Friday evening, when they segued into quickie telephone tributes for George H.W. Bush, followed by Lester Holt narrating the prepared tribute.

One of the film clips was of a little boy in a back-yard rundown, lovingly getting tagged out by the right, gloved hand of an elder, presumably the Bushes we now know as 43 and 41. It was so sweet, people playing the American game with great big smiles and sweeping tags. Mister, I’m a baseball man--Ry Cooder. My conduit to President Bush, the baseball man, came via Curt Smith, a speechwriter during the Reagan-Bush years, who in 1989 invited a gaggle of sportswriters and broadcasters to the White House for a baseball schmooze-fest. I wrote about the President’s glove in his desk drawer. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/10/03/sports/sports-of-the-times-.251-hitter-talking-baseball.html When I heard about President Bush’s passing, I immediately thought of Curt Smith, and his admiration for his former boss. It is well known that President George H.W. Walker was a crier. Wept easily. Smith once told how he was assigned to write a speech for the visit to Pearl Harbor on the 50th anniversary of the attack that kicked off the Pacific war on Dec. 7, 1941. On Saturday I asked Curt for his recollections of No. 41 – and the speech. This is what Curt Smith wrote back: Bush truly loved the game: played, coached it in Texas, mentored players, captained his team at Yale. He made the first two College World Series in 1947-48. He accepted Babe Ruth’s copy of the Babe’s memoir in 1948 as Yale’s captain as Ruth was dying of cancer. He coached all four of his sons in Little League. He took Queen Elizabeth to a baseball game, staged a great event at the White House to honor Williams and DiMaggio on the 50th anniversary of their magical 1941, invited Musial and Yastrzemski to the White House as he prepared to go to Poland to, among other things, christen Little League Baseball there, on and on and on. He and I talked baseball, he had my Voices of The Game at Camp David. Our first meeting he told me, “I’d rather quote Yogi Berra than Thomas Jefferson,” and meant it. He knew more Berraisms than I did! Pearl Harbor evolved from the fact that I generally did “values, inspiration, patriotic” speeches for Bush. I had always read a lot about World War II and was very conversant with Bush’s role in the War. I knew of his great modesty. As I kid he hit a couple homers once. His mother Dorothy eyed him and, referencing the grand Protestant hymn, said, “Now, George, none of this ‘How Great Thou Art’ business.” Bush was naturally self-effacing and deferential, two of the reasons he drew people toward him. He hated to use the word I in speeches. Try writing speeches that way! In any event, our speech staff was constantly frustrated at how the country didn’t know the Bush we did—because of Bush’s dignity, innate reserve, feeling that the President should set an example. (What a concept!) I wanted the country to see the man that we did. In talking with the President, I tried to subtly make this point. Bush, on the other hand, had been 17 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, a Sunday. He had friends who had died. He had gone next day, a Monday, and tried to enlist. The draft board said, in essence. “Sonny, you’re too young. Come back when you’re 18.” He did, enlisting the day he turned 18. Bush, at heart a very sentimental, emotional man—a softie, as he and we knew: again, a reason so many of us loved him — was concerned he would not get through the speech. “I don’t want to break down,” he said. I didn’t tell him I wanted him to break down: that would have been unseemly. I did say that “This will be a chance for you to talk about an event that will show the Nation the kind of person you are.” As things turned out, he didn’t break down, but did choke up; his voice faltered; he was clearly moved. In retrospect, Bush, who almost to the end was unsure whether he could give the speech, was very glad that he did. And in the next 25 years, as a former President, the country came to see almost precisely Bush as we had—sentimental, giving, kind, funny, patriotic—one terrific person. (With great thanks to Curt Smith) Curt did not include this Pearl Harbor story in his terrific recent book, “The Presidents and the Pastime: The History of Baseball & the White House,” published by the University of Nebraska Press. Bush, a .251 hitter at Yale, was surely the best player and biggest fan of all presidents who have tossed out ceremonial baseballs on opening day. They were baseball people, the Bushes, part of the carriage trade that made the New York Giants the elite team of the big city. George Herbert Walker, Jr., uncle of the future No. 41, owned a piece of the Mets, starting in 1962 – a clubby gent who, as I recall, was fine with sportswriters calling him “Herbie.” They were easy to be around, the Bushes. I was lucky enough to meet No. 41 twice, both in baseball settings. I wrote about my second meeting when Barbara Bush passed last May: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/a-quick-chat-with-barbara-and-george-bush However, I did not get as close to No. 41 as my boyhood pal, Angus Phillips, did for the Washington Post. Invited to a dawn fishing trip on the Potomac, Angus reported to the White House a few minutes early and somehow was ushered into the living quarters where he discovered the leader of the free world padding around a hallway, clearly just out of bed. Angus’s classic tale of the visit…and the fishing….is included here: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/sports/daily/dec99/25/phil25.htm George H.W. Bush was the last World War Two veteran to serve as president. He kept his old George McQuinn mitt in his desk drawer in the White House. Whatever else he was, he was a softie. And a baseball man. * * * The New York Times also prepared a magnificent spread on No. 41: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/30/us/politics/george-hw-bush-dies.html https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/obituaries/george-bushs-life-in-13-objects.html In her final days at home, Marie DeBenedettis propped herself in the kitchen of the fabled family delicatessen – Mama’s of Corona, Queens – and devoted herself to teaching her kid sister, Irene, how to cook. Not an easy task, Irene would say. The three sisters had their roles. Carmela Lamorgese was now La Nonna, Grandma, caring for her own family after years of helping run the business. Marie was the chef. Irene had taught school and now her job was to “run around and talk a lot” – that is, coordinate the deli and their awesome throwback pastry shop two doors down. It revolved around Marie – the sweetest person I have ever hugged, optimistic and positive, but a taskmaster in the kitchen as she tried to impart her knowledge to Irene and a few assistants. “One day she said to me, ‘Irene, basil, lots of basil in everything, that’s what makes it taste so good.’” So, that is the secret of life on 104th St. – the reason the tomato sauce, the daily specials, all taste so good. Irene was trying, knowing their sister was not well, could not easily budge from her perch in the cramped kitchen. I dropped into the deli in late spring and asked Marie how her protégé was doing. “All right,” Marie said. “She’s tough on me and the girls,” Irene said later. “She wants us to know everything.” The time came for Marie to go to the hospital a month or so ago. One night Irene counted 17 workers -- younger women with roots in the Bari area of Italy and Latinas from Corona – visiting Marie in a group. “I didn’t know she had that many people working here,” Irene said. One of the workers told Irene, “She keeps saying ‘cavatelli, cavatelli’” -- small pasta shells often stuffed with garlic and broccoli or broccoli rabe. Irene deduced that Marie was reminding the assistant to prepare cavatelli for the regulars who would expect it on Thursday. “She knew who liked what,” Irene told me the other day at the wake. “She would see somebody coming in the door and she would tell the girls to prepare an egg-and-sausage hero.” All that love, all that skill that was Marie DeBenedettis passed away on Sept. 4. The funeral was held on Tuesday, Sept. 11. The Mets, a mile away, where Mama’s has an outlet, held a moment of silence before a game last weekend, via Jay Horwitz, PR man and loyal keeper of the Met flame. David Wright, the captain, dropped into Mama’s to offer his condolences. The prince of Corona, Omar Minaya, who introduced me to Mama’s in 2006, is back where he belongs -- with the Mets. (My first visit with Omar – here.) Mama’s is a family place – new neighbors speaking Spanish, Italian and English, old neighbors who moved away but come back for mozzarella and cannoli, and a steady clientele from the FDNY, the NYPD, the schools and churches and seminaries, and assistant district attorneys from nearby Kew Gardens. (Mama’s is the safest place in Queens.) The institution will go on. Mama’s is officially named Leo’s Latticini, for Frank and Irene Leo, who began the dynasty in the 1930s. “Mama” was their daughter, Nancy, who ran the store with her husband, Frank DeBenedettis. Nancy, who passed in 2009, was such a force in the traditional Italian neighborhood that the public school up 104th St. has been named in her honor. (Please see the lovely article by Lisa Colangelo in that civic treasure, the Daily News:) http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/queens/owner-leo-latticini-best-mama-corona-missed-article-1.437014 The family tradition continues. Carmela's daughter is known as Little Marie....and she and her husband, Fiore Difeo, named their first-born Gina Marie, followed by Anthony and Dominic. Mama's has reminded me that I am a Queens boy. I have introduced friends and family to Mama’s, watched World Cup matches (featuring Italy), chatting with my friend Oronzo Lamorgese, Carmela’s husband, as a guest in the private dining room behind the pasticceria – lavish plates, prepared by Marie and staff. I am sure Marie was as good a teacher as she was a cook. Mama's goes on, with basil. My love and condolences to La Famiglia. http://obituaries.nydailynews.com/obituaries/nydailynews/obituary.aspx?page=lifestory&pid=190164979 Uncle Harold took us on great drives around coastal Maine – the beaches, the woods, the little towns.

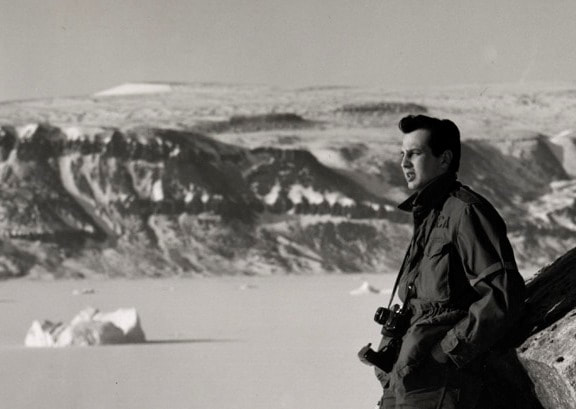

The tours invariably ended near Oak Grove Cemetery in his home town of Bath. “Why don’t we just drive in,” he would suggest. We would park on the narrow lane and walk to the single tombstone for his wife Barbara and their son Roger. Harold’s name was waiting for the date of his death. Roger had died in a car accident near home, after surviving a bullet and malaria in Vietnam. Barbara had lived a long and active life, caring for others, although wracked by bone disease and later diabetes. Harold often talked about her in the present tense, as in “Barbara and I take this road to Boothbay Harbor for the fried fish.” My wife, his niece, and I started visiting Harold Grundy after Barbara passed in 2014. We fell in love with that part of Maine, and at my own advanced age I found myself a new hero, as he casually told stories about surviving combat in the Pacific and building electronic surveillance outposts in Greenland and Guantánamo Bay. But he was wearing down, and it took a village of loved ones to usher him through pain and confusion before he passed on Jan. 4. People in cold climates cannot bury their dead in mid-winter. Harold, stubborn by nature, modest from his Quaker background, precise from his construction career, specified no ceremony, no fuss, for his burial. His two faithful surrogate children, Ace and Cookie, now living in Arizona and Connecticut, arranged for a no-frills burial on May 11. Eric came in from Florida. My wife and I were asked to represent the family, scattered and getting on in years. A few locals heard about the burial, and then a few others, and they got to the cemetery, some using walkers and canes to reach the casket, with the American flag neatly folded on top. The sun was bright, the breeze was chilly, and the funeral director read a few prayers -- as quick and simple as Harold had mandated. A very fit military guy in a red flannel shirt, who had worked with Harold at the surveillance base in Cutler, Me., stood at attention and whispered to me: “Best man I ever met.” Later, eight of us met at a tavern alongside the glistening Kennebec River. We toasted the family, and told a few stories. Ace told how Barbara and Harold used to take him along on so many family outings when he was a kid. And Ace told how Harold approached the mathematical challenge of building basement stairs: “He wasn’t telling me what to do. He was teaching me.” People smiled as they recalled how Harold always had fresh pies and pungent chowders on the stove for company. My wife, the oldest of her generation, remembered a Christmas right after the war, when three young couples were sharing a small house on the Connecticut shore, and how she witnessed Uncle Harold using a tiny saw on a wooden bowl. On Christmas morning, she found a beautiful bed for her doll’s house. Harold always made things. He and Barbara used to peddle his home-made toys at flea markets in the region, and later his friend Eric made a thriving web business out of wooden objects. Nobody wanted to leave the lunch. Cookie, so loyal and capable, who did the paperwork for Barbara and Harold for decades, proposed that our little community meet again next year. We went our separate ways, knowing that Harold was up on the hill at Oak Grove Cemetery, with Barbara and Roger. * * * I’ve written about Harold and Barbara and Maine: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/farewell-to-harold-grundy-of-the-greatest-generation https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/sometimes-a-good-idea-actually-works-out https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/dredging-the-river-in-1941-for-a-destroyer-in-2016 Journalists often rely on first impressions, or only impressions, of people, whether famous or obscure. I “met” Barbara Bush one time. Fittingly, it was in the White House, Feb. 15, 2011, minutes after her husband had been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It was a day of accomplished people – Warren Buffett here, Jean Kennedy Smith there, Bill Russell up there, Stan Musial over there, and Yo-Yo Ma sitting in with a Marine chamber group, with his pal President Obama standing nearby. The kind of magic day that a journalist remembers forever. As the afternoon became more informal, I was in a bustling hallway and spotted former president George H.W. Bush in a wheelchair, after receiving his medal. Standing alongside him was his wife, with her Mount Rushmore presence. My mind went back to a visit to the White House in Oct., 1989, when President Bush held a schmooze-fest with baseball writers, pulling a George McQuinn glove out of his desk drawer. I believe he had worn it in the College World Series when he was a .251 hitter for Yale. Now, in 2011, I saw an opportunity to chat with the old first baseman. “Mr. President,” I began, reminding him how he had displayed his prized glove more than a decade earlier. Did he, I asked, still have the glove? He took my question seriously, but was unable to come up with an answer. Then he turned to the person he clearly relied upon, standing nearby. “Bar,” he began. “Do you know where my old glove is?” We were not introduced, it was all so sweetly informal, and now it was a three-way conversation, with Barbara Bush wracking her memory of where the glove might be. They instantly became Ma and Pa, so vital, so human, trying to place one object in a life that veered from the waspy Northeast suburbs to the Texas oil fields, to China, to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., and now back “home” to Houston. They were Everywoman and Everyman of a certain age, trying to track a baseball mitt – or an old coffee maker or a favorite sweater or a set of books. Maybe they said “attic” and maybe they said “storage” and maybe they said “downsizing.” Bottom line was, they did not know, but they made eye contact with me, and gave me a civil answer, and then other people greeted them, and I politely moved on. I wound up using that quick encounter as my column that day about the importance of sport, as personified by Russell and Musial…and an old first baseman who didn’t know where his glove was. So that is my permanent impression of Barbara Bush – the caretaker, the authority, the rock. My wife reminds me that we heard Barbara Bush speak about adoption at a conference in DC, while she was First Lady. My wife, who was escorting children from India in those years, recalls how positive Mrs. Bush was about adoption, what a good speaker she was. Marianne has been a fan ever since. That same aura comes through in the memories and obituaries today. I had been wary of Mrs. Bush years earlier when I heard she made a comment about the Magna Mater of my lefty family, Eleanor Roosevelt. But there is room for other strong people in this world. The two George Bushes, pere et fils – how admirable, how stable, they seem these days – celebrate Barbara Bush, and, as a quick-study journalist type, I know they are right. Another glimpse of Mrs. Bush: My friend John Zentay, a lawyer, is on the board of the National Archives, where Mrs. Bush gave a spirited talk a few years ago. Zentay said he and his wife, Diana, had recently visited Sea Island, Ga., where the Bushes honeymooned so long ago. Mrs. Bush emphatically said she and her husband had gone back recently and found it so expensive they would not go back. And she meant it. I just read the wonderful obit written (I imagine, years ago) by a grand New York Times reporter, Enid Nemy, now 94, and I found out why Barbara Pierce happened to be born in my neck of the woods, Flushing, Queens, and I learned about the deaths of her mother and her young daughter. f you haven’t read it already: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/17/us/barbara-bush-dead.html I think of that formidable woman I heard at a conference in D.C. and later met in a hallway at the White House, and I give thanks for the karma that put us in that same place, for a few fleeting moments. My quick impressions stack up perfectly with everything I have heard or read. “Bar.” That’s what her husband called her. Three letters, and so strong. * * * From my friend Curt Smith, former speechwriter for President George H. Bush: Barbara Bush was an extraordinary woman—much more complex than her public image. She was strong, a woman of great character, the rock of her expansive brood, the protectorate and center of her husband’s life, an enormous credit to her nation, loved around the world, and among the truly popular First Ladies in American history. In a book on her husband, I called her “Barbara Bush, Superstar.” She was. Bush would employ self-deprecating humor to suggest an identity crisis, living in her shadow. In fact, he knew what an enormous asset she was. She also read potential aides and real-life enemies more quickly than he did. She was tougher, in a way. As you know, their three-year-old daughter, Robin, died of leukemia in 1953. She ultimately recovered, at least on the surface, discussing it in the 1990s and 2000s. To this day, the President cannot discuss it without his voice choking, unable to proceed. Mrs. Bush knew this vulnerability, and was his most ardent—fiercest—defender, there always. She was always graceful to my wife and me, as she was to every American she met. She was a class act, in the classic American way. We don’t get nearly enough them of them anymore. Her religious faith made her face death with the same courage that she confronted life. God bless her. ---Curt Smith was a speechwriter who wrote more speeches than anyone for Pres. George H.W. Bush during his presidency. He is currently a senior lecturer of English at the Univ. of Rochester and is the author of 17 books, including a history of Presidents and Baseball, to be published in June. It seems that the Bushes chose their wives well. A friend of ours is an Elizabeth Wharton scholar. She told us about how letters from Wharton were found in the attic of her housekeeper.

There was concern that when they were put out for auction a buyer might cut out Wharton’s signature and sell them individually. Laura Bush asked Yale to bid but was told that the university could not afford to. Laura said to buy the letters and not to worry about the cost. She found someone to finance the purchase. Our friend later had access to the letters and wrote a book about them. Several years latter, Sandi and I saw Laura on the Highline in Manhattan. As she passed we said, thanks for Wharton letters. In that brief second, she gave us a big smile. –Alan Rubin Ed Charles played only 279 games for the Mets but he touched New Yorkers – really, everybody who met him – with his humanity. This was apparent on Monday at a farewell celebration of Charles in Queens, his adopted home borough. People told stories about him, and I kept thinking of all the ways, Zelig-like, he popped back into my life. His 1969 Miracle Mets teammate Art Shamsky told how he and Charles and Catfish Hunter and Jack Aker were making an appearance at a boy’s camp “up near Canada somewhere” and how Ed Charles drove – “one mile below the speed limit, always. Ed never went fast. That’s why they called him The Glider.” When they finally got there, the players elected Ed to speak first to the campers. After 45 poignant minutes, Shamsky said they had learned never to let that charismatic man speak first. Everybody smiled when they talked about Charles, who died last Thursday at 84. His long-time companion, Lavonnie Brinkley, and Ed’s daughter-in-law, Tomika Charles, gave gracious talks, and his son, Edwin Douglas Charles, Jr., made us smile with his tale of playing pool with his dad, and how the old third baseman never let up, in any game.  A retired city police officer alluded to Ed’s decade as a city social worker with PINS – People in Need of Supervision – and how Ed reached them. People talked about barbecues and ball games and fantasy camps with Ed, how it was always fun. As sports friends and real-life friends at the funeral home talked about Ed’s long and accomplished life, I thought about how we connected over the years, in the tricky dance between reporter and subject. ---The first time was between games of a day-nighter in Kansas City, on my first long road trip covering the Yankees for Newsday, August of 1962. Old New York reporters were schmoozing in the office of Hank Bauer, the jut-jawed ex-Yankee and ex-Marine with two Purple Hearts from Okinawa. Ed Charles, a 29-year-old rookie – kept in the minors because of race and bad luck – came to consult the manager, maybe about whether he was good to go in the second game. I watched Bauer’s face, once described as resembling a clenched fist, softening into a smile. “Bauer likes this guy,” I thought to myself. “He respects him.” (I looked it up: Ed went 7-for-12 with a homer in that four-game series.) --- We met in 1967 when the Mets brought him in to replace Ken Boyer at third base. During batting practice in the Houston Astrodome, the first indoor ball park, Ed summoned me onto the field, behind third base, shielding me with his glove and his athletic reflexes. “Look at this,” he said, pointing at the erratic hops on the rock-hard "turf" -- one low, one high, a torment for anybody guarding the hot corner. I must have stayed beside him for 15 minutes and nobody ran me off. I have never been on a field during practice since. That was Ed Charles. Easy does it. --- We had a reporter-athlete friendship, but there are always gradations. During a weekend series in glorious mid-summer Montreal in 1969, somehow there were three VIP tickets for a Joan Baez concert. I went to a brasserie with Joe Gergen of Newsday and Ed Charles and then we saw the concert, with Baez singing about love, and the Vietnam War. --- The Mets won the World Series and Ed went into orbit near the mound, but then he was released, his career over, with a promotions job with the Mets gone over a $5,000 dispute in moving expenses. But I was walking near Tin Pan Alley in midtown in 1970 and there was Ed, working for Buddah (correct spelling for that company) Records. He was destined for Big Town. He later had some ups and downs in business but patched things up with the Mets and settled into his groove as poet/Met icon. ---When Tommie Agee died suddenly, Ed was working at the Mets’ fantasy camp, and he took calls from reporters to talk about his friend. Ed Charles, as this New Yorker would put it, was a mensch. --- In 2012, the 50th anniversary of the Mets, Hofstra University recruited Ed to give a keynote talk on his poetry and his deep bond with the Mets. I was asked by my alma mater to introduce him, and I suggested to Ed that I could help him segue into his poems. He smiled at me the same way he had calmed down Rocky Swoboda and all the other twitchy Mets kids back in the day. “I got this, big guy,” he told me – and he did. --- Last time I saw him, a few months ago, I visited his apartment in East Elmhurst, Queens. Lavonnie was there, and I brought some of that good deli from Mama’s in nearby Corona, plus enough cannoli to last a few days. Ed was inhaling oxygen confined to quarters. I saw sadness and acceptance, He let me know: he knew the deal.

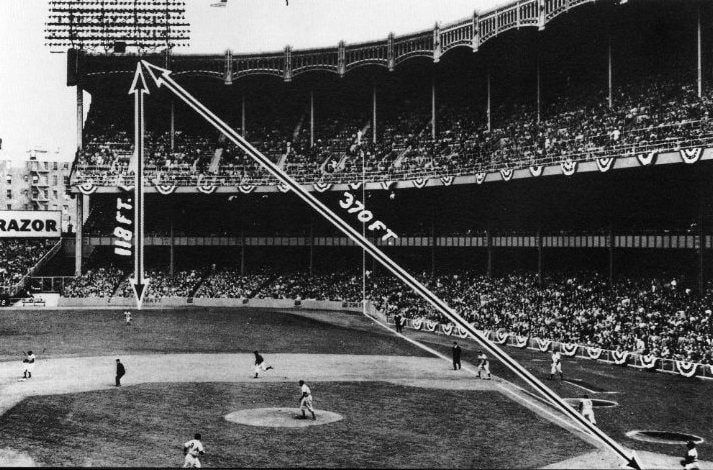

On Monday, The Glider had his last New York moment. There will be a funeral in Kansas City on Saturday and he will be buried, as a military veteran, at the national cemetery in Leavenworth, Kans. The funeral home Monday was a few blocks from the first home owned by Jackie and Rachel Robinson in 1949. The first Robinson home, on 177 St. in the upscale black neighborhood of Addisleigh Park, has been declared a New York landmark, as written up on the StreetEasy real-estate site (by none other than Laura Vecsey, a sports and political columnist.) Ed Charles often talked about taking inspiration from sighting Jackie Robinson as a boy in Florida; the proximity of the funeral home and Robinson home was a sweet coincidence, the family said. The karma was unmistakable. Like Rachel and Jackie Robinson, Ed Charles encountered Jim Crow prejudice, but came to New York and won a World Series, and left a great legacy of talent and character. (The Charles family has requested that any donations go to worthy causes like: The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City or the Jackie Robinson Foundation in New York)  Yankee Heaven. The real Stadium. The Mick hits the facade. Over and over again. Yankee Heaven. The real Stadium. The Mick hits the facade. Over and over again. Big Al passed last Sunday morning. What that means – what I think that means – is that I will not be getting any more emails out of the blue, like: “Just asking. How good a clutch hitter was Yogelah, anyway? Ask your friend Newk.” This was a very personal barb, aimed not just at me but at the admirable Don Newcombe, still working for the Dodgers out in LA, who got creamed by Yogi Berra for two – count ‘em, two – two-run homers in the seventh game of the 1956 World Series. Oh, yes, Big Al remembered. And made sure to remind me. Big Al was a loving member of his own family, but his special charm was getting on a point and pushing it. This made him a great lawyer for a major insurance company, according to Joseph LoParrino, for whom Al was mentor and friend. “Al and I debated every major sports and news story since 1999 and since email was invented,” LoParrino wrote to me. “When the Tiger Woods scandal broke - my phone buzzed. His commentary made you fall over laughing. I could press his buttons in any category.” Big Al was a master in button-pushing. My first contact with him was via his company envelopes and company stationery, before the advent of emails. Big Al would scribble – penmanship obviously not his forte in the public schools of East Queens – lengthy screeds about how I had insulted the current Yankees or, much much worse, The Mick. Al – who was a decade younger than me – thought part of the problem was that I had attended Jamaica High in the 50’s whereas he had attended rival Van Buren High in the 60’s. (He couldn’t blame college, since we both attended Hofstra as undergraduates.) Al let me know, in six pages of briefs, that he knew more about sports than I did because he had played basketball and baseball for the demanding Marv Kessler at Van Buren. I loved his descriptions of Kessler, vilifying him in Queens billingsgate, for sins committed in games or practices. (Many years later, Kessler praised Big Al as player and mensch; Al felt that praise was a tad late.) Every journalist would be thrilled to have a critic like Big Al. We became mail pals, bonding over the long-lost Charney’s deli at 188th and Union Turnpike, and zaftig Queens girls, and Alley Pond Park, and the way the old Knicks played, and really what else is there? Al became my Yankee Everyman, a stand-in for all of them. What he felt, they all felt. Eventually we met for a few dinners at the old Palm on the west side of Second Avenue. Al would deride me for ordering broiled fish and salad rather than the double primo beef and potatoes. Sissy. Weenie. And other Marv Kessler terms. Sometimes he would order a full meal to bring home to his mother who lived in New Jersey. He was such a Palm regular that his caricature was on the wall of valued customers, celebrities or just people who liked to eat beef. (Alas, that caricature seems to have been lost in the move across Second Ave.) By then, Al was no longer the rail of a forward that Marv Kessler had berated back in Queens Village. He was Big Al, Manhattan bachelor, Eastside Al on one email handle. We would talk politics, and he would tell me tales about his service veteran/fireman/tradesman/paper hanger father who gave up his love of the Brooklyn Dodgers for his Yankee-fan wife, Ruth, who had seen Gehrig play. Al was proud to tell me how his mother loved Andy Pettitte more than she loved him. He ascribed it to Pettitte’s schnozz but knew it was about Andy’s gentleness. With no context whatsoever, Al dropped little e-bombs on me about or how Casey Stengel stuck with lefty Bob Kuzava against Jackie Robinson in the seventh game of 1952 and how Billy Martin raced across the windy, sunny infield to catch the popup. Always there was Yogelah, golfing homers off his shoetops, an endless loop of homers off poor Newk (one of the great people I have met in baseball.) Al went silent one year, and I worried, so I sent a letter to his office, and somebody told me he was out on sick leave. When his mom passed in 2009 he took over her house in New Jersey and lived near his sister and her family -- and raved to his friends at work about the joys of the Jersey suburbs. Via the email, he never stopped taunting me, or raving about the Yankees and in particular The Mick. (He loved Sandy Koufax, too.) One time he spoke for all New York fans who flocked to the ball parks on opening day over the decades: streeteasy.com/blog/baseballs-opening-day-nycs-boroughs-influenced-its-pro-teams/ Recently I sent an email: “Al, where are you?” His sister, Roberta Taxerman Smith, emailed me Monday morning saying Big Al had passed Sunday at 67 and the funeral would be held Tuesday in New Jersey. His paid obit was in the Times and on legacy.com: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?n=alan-taxerman&pid=188012820 I smiled when I noted that Big Al passed in the Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck. He was a loyal Jew, and a most ecumenical dude, as many of us were in Queens. He and I exchanged greetings at Rosh Hashanah and Christmas and the first day of pitchers and catchers and other holy days. He knew I had grown up with mostly Jewish friends and he called me “landsman.” When I found out, via DNA testing, that I am 47 percent Jewish, via my father, who was adopted, Big Al's reaction was: I told you so. Then again, that was often his reaction. Roberta Taxerman Smith told me Al believed, to the end, that the docs were going to take care of him and he never complained. He had saved his complaints for Joe Torre’s strategies, and we argued over that, too. Here’s what I really hate about losing Big Al: he I were both looking forward to seeing Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton in the same lineup, the same pinstripes. Murderer’s Row, 2018. If there is justice, on Opening Day they go back-to-back. Maybe Big Al will send me an e-mail. My wife’s uncle, Harold Grundy, passed early Thursday at the age of 95. He was an American hero – a carpenter who learned complex engineering skills, who kept Navy ships steaming in murderous waters in World War Two and later supervised the building of observation stations and nuclear plants. He was a survivor – of bombs in the Atlantic and Pacific, of winters in the Arctic, a wartime storm off England, a typhoon in the Pacific, and of life itself. His only child Roger came home wounded from Vietnam only to die from a car wreck on a Maine highway. His wife Barbara was wracked by diabetes -- and he took care of her, with the help of dear friends. Everybody knew him in Bath, Maine, Barbara’s home town. After Barbara died in 2014, Marianne recognized the need to visit her uncle once in a while. At 93, Harold would have thick, rich chowder on the stove and fresh fruit pies baking in the oven. Harold would take us on little outings from Bath – beaches and fish restaurants and back roads. He took us to coastal towns that looked like a setting for “Carousel” and fish-fry stands and old forts. He talked about Barbara in the present tense: “Sometimes Barbara and I drive up this road in the late afternoon.”

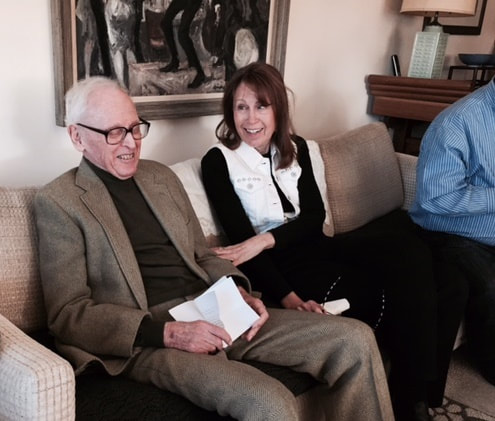

His education had ended in high school. He and his older brother left Connecticut in 1940 for a job dredging the Kennebec River to accommodate the large warships being built for what was coming. From his cottage alongside the river, he would tell us about rowing explosives into the middle of the river. In wartime, his acquired technical and engineering skills were essential to the military; he helped win one war and fight the Cold War. He was the last survivor who had served at observation posts in Greenland and Cutler, Me., and Guantanamo Bay, keeping an eye on our new best friends from Russia. However, because he was technically a civilian employee (ducking the same bombs as the military personnel), he was denied a pension by the U.S. government. Somehow, he was not bitter. Harold moved all over the world, building sensitive structures. Recently, we mentioned that one of our daughters lives near the nuclear plants at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. “Don’t worry,” Harold assured us, “I can tell you we made them double strong.” He had a Zelig-like way of being everywhere. He once chatted with a young senatorial candidate named John F. Kennedy in a train station in Boston; Winston Churchill popped out of No. 10 Downing Street and said hello to Harold and a few other tourists. One time we were driving near the coast and Harold casually mentioned he had helped build a house for Margaret Chase Smith when she was a senator. With her politician’s memory, she once recognized him when she got off a government plane at Cutler, and asked him to accompany her on her visit. People seemed to detect the civility and knowledge behind his humble bearing. He was so valuable to a construction company that they often flew Barbara to join him overseas, and they helped with her medical treatment. When Harold was home in Bath, between projects, he and Barbara, with her crippling diabetes, expanded a house on Washington St. He built houses and boats and docks and staircases for banks and chicken coops that were more handsome and sturdy-looking than some homes along the highway. Harold and Barbara started a little woodworking business – in their spare time, you understand – which has become a major business for a close friend. Harold and Barbara had a legion of dear friends who helped them: Cookie, Ace, Eric, Martha A, Martha B, Ann, Germaine, Diane, Rich and Suzanne, Bill, his nephew Dr. Paul, many caring medical people in the area, Kristi at the Plant Home, and people in shops and banks and drugstores, who fussed over them, in a real community. Two years ago, the Peary MacMillan Arctic Museum & Arctic Studies Center at nearby Bowdoin College held an exhibition of 193 photographs Harold took when he was based in Greenland. Harold’s family – including siblings in their 90s and late 80s – came in from New England and Florida for a reunion, in Harold’s most public moment. Harold came from hardy stock -- Quakers named Watrous and Crouch and Whipple who settled the eastern Connecticut coast and people named Grundy and Clegg and Schofield who thrived in Lancashire during the Industrial Revolution. But even these rugged folk wear down. Harold was fading the last time we saw him, on his 95th birthday in September. He had moved into a lovely retirement home, but his energy was gone and he could not enjoy the party. On Wednesday night, Cookie, a surrogate daughter to Harold and Barbara, who supervised their paperwork, was visiting from Connecticut, to be near him. Harold passed as a wintry storm roared up the coast. Come spring, Uncle Harold will be interred in the lovely hillside cemetery where he used to take us to visit Barbara and Roger. In recent weeks, as I thought about Harold and Barbara and Roger, my mind moved to a song about the release from pain – “Agate Hill,” by Alice Gerrard, recorded by the great Kathy Mattea. As I type this in the snowstorm, I think of Roger and Barbara and Harold together, building and cooking and fishing on some celestial version of coastal Maine, and I hear a line from the song: “Wild and free again, oh it will be as then.”  IN MEMORIAL, GERMAINE BOYNTON Harold often talked about his in-law Germaine who lived further up US 1. She invited us to lunch last spring and cooked a French-Canadian specialty and showed us the work and studios of hers and her daughter Diane, two formidable and artistic ladies. Germaine passed in hospice Saturday morning, two days after Harold.  Roy Reed, Hidin' Out. Univ of Arkansas Roy Reed, Hidin' Out. Univ of Arkansas While waiting for the Alabama results to solidify Tuesday night, I was reading the obit for Roy Reed. Roy was the great stylist when I was a rookie on the highly literate National staff of the New York Times in the early ‘70s. He could describe the exotica of New Orleans, where he was based, with the same fervor and grace he had shown in the head-breaker Deep South of the Civil Rights decade. For me, he was the correspondent to emulate. I even noticed the conservative dark-blue pinstriped suits he wore on more formal occasions, making him look like a senator. Roy Reed was from rural Arkansas and he never forgot it. I know he would have loved the campaign in Alabama – a candidate who prosecuted the murderers of little black girls vs. a candidate who stalked teen-agers in shopping malls and outside public buildings. Fortunately, the Times and other great journals have deep and talented staffs these days, to capture the ludicrous spectacle of a hustler from New York conning people out there in America. Also fortunately, I was able to hear Howell Raines, another of those great southerners who have graced the Times, talking about his beloved rural Alabama on MSNBC Tuesday night and also via a recent op-ed piece in the Times. There was a great tradition of writers on that National staff when I joined it in 1970. Gene Roberts, who had covered civil rights and Vietnam, was the national editor, expanding his staff, and he called this young baseball reporter and said, “I like the way you rot.” I sussed out that this was the charming accent of a self-styled “freckle belly” from eastern North Carolina who meant “the way you write.” Gene sold me. He and his deputy, David R. Jones, sent me off to Louisville to cover Appalachia. What a staff. Roy Reed in New Orleans. My dear friend Ben Franklin plus John Herbers and so many other good people in the Washington bureau. Jon Nordheimer and Jim Wooten in Atlanta. Paul Delaney in Chicago. B.D. Ayres in Kansas City. Jerry Flint in Detroit, John Kifner in Boston and so many others further from my region. (There was only one African-American, Delaney, and no women; the only way I can explain it is, “It was 1970.” Further down the decade, under Dave Jones, the NYT added Grace Lichtenstein in Denver as the first female national correspondent and later Molly Ivins, Judith Cummings, E.R. Shipp and Isabel Wilkerson, who would win a Pulitzer under Soma Golden's editorship.) In my years, a kind day editor, Irv Horowitz, in New York, kept track of us, and great copy editors had the time and mandate to ask you to rewrite something so it would read better. We communicated by telephone – not email and not cell phones. Such a primitive era. I relied on these older professionals to teach me something, anything, by osmosis. I would like to correct one statement in that obit concerning Roy Reed: It said he was down the road getting a soft drink when James Meredith was shot on his epic protest walk through Mississippi in 1966, and that Roy’s respectful colleagues later presented him with a Coke bottle trophy that said “WHERE’S ROY REED?” in memory of his brief absence. The fact is, there was another day when Roy turned up missing. Dave Jones, our ringmaster in New York, was trying to find someone to get to a story in the South that seemed urgent at the time. (I can no longer remember what it was.) Dave tried me in Louisville. No answer. Dave tried one of the Atlanta guys. No answer. Dave tried Roy Reed in New Orleans. No answer. Ever diligent, Dave solved the problem some other way, and the world went on. A few days later, the mystery was solved. A delightful March zephyr had moved north from the Gulf into Louisiana, into Georgia, and even to the southern banks of the Ohio River in Kentucky. All three correspondents had been, shall we say, indisposed. On the phone, I asked Roy where he had been when the office was looking for us. In his Arkansas drawl, Roy said: “Hidin’ out.” I adopted his phrase for times when I was unfindable. Bless the era before cell phones. Bless the southern phrases, the southern outlook, I learned to understand from my colleagues, better reporters than I ever would be. And bless Roy Reed, for writing about a region that continues to produce great stories, from the new generation. ------------------------------------------------------- Nina Simone was voted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this week. She passed in 2003; what took them so long? Not sure what Simone would have thought about that, but she surely would have loved the vote in Alabama Tuesday night. A candidate who was receptive to the integration of his high school back in the day beat out a religion-spouting accused pedophile who thinks slavery came during a good time for families in America. Simone knew it all, put it into her music. She was an American treasure. She mentions Alabama way up high in her signature song, “Mississippi Goddam.” Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Nina Simone:  Ray Robinson and Ernestine Miller at his 95th party Ray Robinson and Ernestine Miller at his 95th party As he passed 80, Ray Robinson had an idea for a new book – the last recorded words of prominent people. He knew how to write books, of course – the Lou Gehrig bio, the Christy Mathewson bio. He was a magazine editor and a freelance writer. The book came out in 2003, when Ray was 83 – “Famous Last Words: Fond Farewells, Deathbed Diatribes and Exclamations Upon Expiration,” published by Workman Publishing. It fits in the hand or the pocket. Perfect quick-take reading. Perfect little gift. This is a blatant plug. Ray would approve. Alas, Ray Robinson passed on Nov. 1. He would have been 97 on Dec. 4 and was to be honored by a coterie of baseball buffs who meet monthly in the city. Ray’s last words? I don’t know, but I talked to him the night before. What was on his mind was a perfect guide to this grand old man of New York and Columbia University and publishing. In our last chat he did not bring up seeing Fidel Castro in Havana or how he met Lou Gehrig as a young New York fan or how he spilt ink on Lefty Grove while asking for an autograph at Yankee Stadium, or his activism with the ALS Association of New York, in homage to Gehrig. Neither did he tell the great story of how a precocious New York girl named Betty Perske called him a “cheap SOB” or maybe it was “cheap bastard.” This underscored link will explain the brief meeting of Ray and the future Lauren Bacall.) Among Ray’s last words to me:

Ray’s passing will leave a huge gap in our lives -- for Jerry, our token ball player, who escorted Ray to the doctor, and Ernestine, who fussed over Ray, and Darrell, one of the originals from 1991 (!), and Lee and Marty and Willie from our group, and Bob and Jeremy, the busy superstars, plus Al and Rosa, who knew Ray and Phyllis forever, and all the other buffs who sat around the table once a month and talked baseball and politics and everything else. We’ll meet on his birthday, I’m sure, and try to remember some of Ray’s good stories. It was my first visit to Las Vegas. I was covering a Mets trip to the Coast in 1966 or so, and there was a day off between LA and San Francisco.

My pal Vic Ziegel of the good old New York Post said, “Let’s go to Las Vegas.” Vic had been there before. Flights were cheap. Food was cheap. The only thing that wasn’t cheap was the gambling, but I don’t gamble. Long story. I watched Vic play blackjack and I watched life in Las Vegas. The hotel lounge was also inexpensive. By doing the math in Rickles’ obituary in the Times Friday, I deduce that he was around 40, but in a way he was ageless. Bald. Profane. Cranky. What’s it to you? He had a theme: Anybody who came to see him in that lounge was truly desperate. He pointed out a young couple and wondered if they were married, or cheating on spouses. He pointed out a young man: “He’s thinking, I’m in Las Vegas, I can get rid of my pimples.” Then he recognized Vic as a member of the tribe. A landsman. “Look at that nose,” he said. “What’s your name?” “Vic.” Somehow, Rickles deduced that Vic was the sportswriter from the Post. “Vic Ziegel!” screamed Don Rickles from Jackson Heights, Queens. (Queens boys are a yappy lot.) “I love you guys!” – meaning the good old Post. (I did not count.) Rickles thought about it for a while. “What’s a Ziegel?” he asked the crowd. Comedic pause. Then he touched his own beak. “It’s an eagle. A Jewish eagle. A Ziegel.” That’s all I remember, except laughing a lot. I’m sure Vic could re-create the entire dialogue but unfortunately Vic left the stage in the summer of 2010. He had introduced me to a lot of good stuff on the road – “Beat the Devil” in Cambridge, Mass., him chatting up jazz musician Roland Kirk in some all-night coffee shop on the square in Cincinnati. And Rickles. In 2015, I saw an aging Don Rickles on the Letterman show; I noticed the immense respect Letterman had for him, getting him through the gig. Now Rickles has bowed out. But every time I went back to Las Vegas – to write about boxing or an entertainer – I remembered Don Rickles in that lounge. Before I tell my Jimmy Breslin-Casey Stengel story, let's talk about bad timing for obituaries. (For example: Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis both died on Nov. 22, 1963.) Likewise, it is not a good career move to compete with Jimmy Breslin, “the outer-borough boulevardier of bilious persuasion,” as Dan Barry calls him. Chuck Berry died the same weekend as Breslin; the Times rolled out the big guns for his strut and the clanging of his guitar, outside the schoolhouse, urging boys and girls to come out and play. John Herbers was also honored with a Times obituary on Monday. He was 93, one of the great reporters of the civil-rights era, a gentleman all the way who politely treated me like an equal when I joined the national reporting staff. He had been in bad places – Emmett Till’s murder – and never lost the unassuming air of a small-town southerner. Bob McFadden and the Times did right by John Herbers: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/18/business/media/john-herbers-dead-times-correspondent.html Okay. Here’s my story about Jimmy Breslin, my fellow Queens boy. Elderly editors still marvel at his imagination in the wonderful interviews he turned in for $10 fees on long-forgotten sports magazines. In 1962 the New York newspapers acknowledged the Mets' raffish ineptitude early on. By late July Sports Illustrated dispatched Jimmy for his take on the worst team in the history of baseball. Breslin arrived in St. Louis the weekend of Casey Stengel’s 72nd birthday, and watched them bumble away games. One evening the club held a party for Casey in the rooftop room of the Chase-Park Plaza. Casey greeted the headwaiter, who had once tossed batting practice for visiting teams in the old Sportsmans Park. Casey imitated his motion, remembered his nickname. I was fascinated by Casey and never left his side all evening. Breslin was also there, observing. If anybody was taking notes, I do not remember. A year later, a Breslin book came out, entitled "Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?" a plea ostensibly uttered by Casey during his long monologue that evening in St. Louis. Not long afterward, Breslin called me for a phone number or something and at the end I said, "Jimmy, just curious, I was at that party for Casey, never left his side, and I don't remember him ever saying, 'Can't anybody here play this game?'" Long pause. "What are you, the F.B.I?" Breslin asked, his Queens accent turning “the” into “duh.” Years later, Breslin conceded he just might have exercised some creative license. Casey never complained about being misquoted. He would have said it if he had thought of it. That was the thing about Jimmy Breslin. He got the inner truths. He had an insight into people’s hearts, almost like a mystic or a psychic. Given his imperfections and his imaginations, he was a universal voice. He was also a very local voice. As the world becomes homogenized, we lose the local voices, the salt and the spices that make life exciting. (Fortunately for readers everywhere, Corey Kilgannon is covering Queens for the Times.) Chuck Berry caught the feel of Route 66 (“Well it winds from Chicago to L.A./More than 2000 miles all the way/Get your kicks on Route 66.” Makes you want to rev up the engine. John Herbers reported from the Deep South, which he loved and sometimes lamented. Jimmy Breslin understood Queens…and the world. He has not been well for years. I would have loved to read him on the scam artist from our home borough. * * * MUST READ: Dan Barry's personal tribute to Breslin on the NYT site: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/20/insider/dan-barry-way-back-with-jimmy-breslin.html?smid=fb-share Our friend Ina sent this video from a live French broadcast. World was never the same.

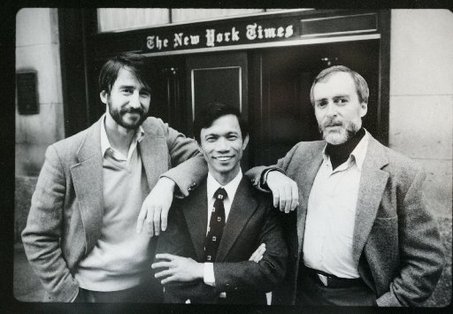

The great journalist Sydney Schanberg died the other day at 82.

(Please see the lovely tribute by Charlie Kaiser, another ex-Times person:) www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/07/the-death-and-life-of-sydney-schanberg I was more of an admirer than a close friend, but we had one moment of contact that I probably recalled better than he did. This was on the spring day in 1976 when he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize after having stayed behind in Cambodia to write about the ravages of a society gone mad. He had become separated from his colleague, his friend, his brother, Dith Pran, who was still missing. I knew Schanberg only as a presence who moved through the city room now and then when he was on home leave. Foreign correspondents have an aura. I knew I could not do what they do, and I admired them greatly. On Pulitzer day, I was a cityside reporter, covering the suburbs, but if the city editor spotted you walking and breathing you could get sent anywhere – a shootout in Brooklyn, an assassination in Bermuda, a visiting king or prime minister in our town. One editor asked me to interview Schanberg for the profile of him in the paper the next day. He was surrounded by friends and I introduced myself and we walked to a less noisy corner and I started with a very general question. This gutsy correspondent who had survived the Khmer Rouge began to cry, and then he began to sob. I did what reporters should do. I went silent and waited for him to make the next move. He was a pro. He gathered himself and managed to say a few things: “I accept this award on behalf of myself and my Cambodian colleague, Dith Pran, who had a great commitment to cover this story and stayed to cover it and is a great journalist.” Schanberg told me he had spent the last year “in a state of deep decompression – I lost a lot of friends over there.” I knew enough not to go much further. I typed up his words, which were in the paper the next day. * * * In 1979, Schanberg’s friend, his brother, made it over the Thai border and soon became a photographer for the Times, a sweet and slight man who made us happy just by being alive. The two buddies got to watch Sam Waterston and Dr Haing S. Ngor portray them in the movie, “The Killing Fields.” (Dith Pran died in 2008.) * * * Sydney was appointed Metro editor in 1977 shortly after I had taken a new post reporting on religion. The Times already had an expert on theology and religious history, and Sydney did not think they needed a second reporter on such a soft beat. He said he would find something else for me. I was enjoying the beat – Hasids one day, nuns the next day, Evangelicals the day after that. I did not want to get shifted. A few days later I just happened to be having lunch with the rabbi who was the spokesman for the Orthodox wing of Judaism in North America. I allowed as how I was feeling a bit glum that day because they were cutting back on the religion beat. My rabbi thought that was too bad because the Orthodox liked the way I, a Christian, wrote about them. It took me 10 minutes to walk from Lou G. Siegel’s on W. 38th St. to the old Times building on W, 43rd St. When I reached the newsroom, Sydney spotted me, and with a mixture of annoyance and possibly admiration he said, “Aw, fuck it, you’re staying on the beat.” I asked no questions but I assumed my rabbi had called a higher-up (not that Higher-Up) and arranged things while I was walking five blocks on Seventh Ave. Sydney held no grudges. He played hardball; he understood it. The next spring, he called me to his desk and said Passover was starting that night and could I get him a Haggadah, the guide to the rituals of the Seder. “Pretty contemporary,” he said. “But not too liberal. You know.” Oh, that Haggadah. I took the No. 1 train uptown to a Judaica bookstore, rounded up a few Haggadahs, and presented them to Sydney. I never asked how the Seder went. He was a hard editor to work for because, like most great reporters, he was used to cutting his own deals; after all, he had defied his own editors by not leaving Cambodia. He was not so good on leadership, on listening to his staff, but he was smart and tough and talented, and I admired him greatly. Later he wrote a column and inevitably butted heads with his own editors, and left the Times. Over the years we met at Times get-togethers and funerals, and we got along fine, old colleagues who had been through stuff together -- but not the kind of stuff he had seen in Cambodia. Every time I saw him, I thought of him crying in the City Room for his missing buddy. No sport carries a sense of community like tennis. Even with gigantic prize money and swollen retinues of today, the sport remains somewhat a caravan of gypsies familiar to each other, even though their occupations vary – players, coaches, hitting partners, significant others, moms and dads, agents and publicists, plus the specialists who cover the sport: the peripatetic photographers plus the scribblers and babblers, as Bud Collins called himself and his colleagues.