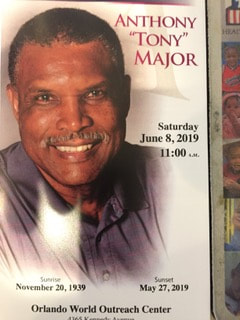

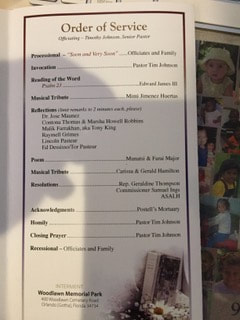

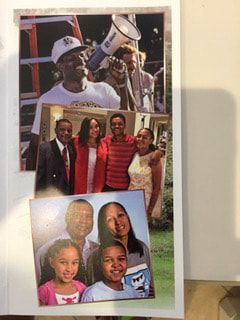

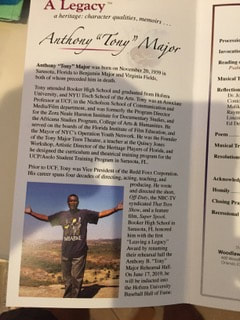

Tony and Sid: Just Like the Old Days Tony and Sid: Just Like the Old Days Only a few months ago, Tony Major was playing 3-on-3 basketball in an over-75 tournament. He could get off his feet, could pop jump shots from the corner. Sent videos back north so his friends could see. He was an athlete and an actor and now a teacher and documentarian at the University of Central Florida, working on a film about Trayvon Martin. He was looking forward to June 17, when he would rejoin some old baseball teammates from Hofstra, when their 1960 team will be inaugurated into the school’s athletic Hall of Fame. Instead, Tony passed suddenly on May 27, at 79. We just heard about it, and a lot of us who knew him back in the day are gutted by this news. Tony made a quickie visit to campus last October, after half a century. He spent part of the day with old jock friends, another part getting a tour of the new communications building from two nice officials and also visiting the playhouse where he had learned to speak Shakespearean. We were all invigorated by his youthful presence. At lunch, he told us about his life. We knew him as somebody who played three sports, but he felt Hofstra was not ready for a black quarterback and he was not big enough to star in basketball. He was a useful member of the 1960 baseball team that won the grand old Met Conference but could not play in the NCAA tournament because of exams. A son of Florida, he had commuted every day to Long Island from Harlem where his mother now lived. He told us about how he gravitated to the great drama department, had tried out for roles in the annual Shakespeare Festival. Laughing at the memory, he described how a black man from the South had learned to shape his speech into the cadence and pronunciations of Shakespearean English. But he did it. And he kept acting, in the city at first. Later, he graduated from New York University Tisch School of The Arts and also taught film production and producing at NYU for two semesters. His baseball ability and knowledge got him a minor role as the backup catcher in the 1973 movie “Bang the Drum Slowly.” He saw young Robert De Niro playing a dying catcher, crouching behind the batter, extending his hands too far. Tony told us how he had passed along some tips about not getting fingers broken by the bat or a foul tip. He moved to Hollywood, playing some bit parts, but also learning about television production. One year he worked with the Dolly Parton show – and raved to me about her intelligence and kindness. And then he moved to Florida, where the university was expanding in Orlando. He began making documentaries, often with an African-American theme. He married late, a woman from Africa, and they had two children, both still in school. “That’s why I’m still working,” he said, laughing. He had so much going on, and now he was reconnecting with some old teammates, plus me, a student publicist who sometimes traveled with the baseball team. Tony had a gentle soul, did not hide the sting of stereotypes. He felt he was used as a pinch-runner in baseball when he could have played more. He recalled road trips to the Mason-Dixon Line, circa 1960, when black players were restricted in the team hotel. And after that, he created a joyous persona, a productive life and career. Early this year, Tony sent me some photos and videos of the over-75 basketball tournament in Florida. There he was, off his feet, getting a rebound, putting it back in. And there he was guarding Sid Holtzer, a former Hofstra basketball player, also still in good shape. In one staged photo, Tony was waving his hand in Sid’s face. Sid never liked that, Tony said. Still didn’t. He giggled at his own mischief. We were looking forward to his next trip north, on the 17th. Instead, there was a funeral on June 8 in Orlando. If there is any lesson to this, it is: reconnect with old friends sooner, and treasure them. * * * Note: Sid Holtzer, another athlete and friend from Hofstra, attended the service and thoughtfully sent photos from the program. (From the University of Central Florida:) https://www.ucf.edu/news/longtime-professor-tony-major-remembered-for-contribution-to-film-ucf/ http://www.nicholsonstudentmedia.com/news/he-brought-hollywood-and-filmmaking-to-orlando-and-ucf-faculty/article_762c9ad0-86c1-11e9-9af6-9b3c9e59c4c9.html

Hansen Alexander

6/7/2019 01:28:20 pm

George my friend,

George Vecsey

6/7/2019 02:44:19 pm

Hansen: Thanks. I honor Hofstra because... they took me in, third-quadrant in my high school class, underachiever, and the small school let me try things, and provided some administrators of high character and some terrific teachers (plus my yearbook co-editor, whom I married) And the connections continue. My athlete friends from there are among the best people I know -- true student-athletes. And Tony exemplifies it. 6/7/2019 05:27:04 pm

Dear George, thank you for that beautifully written remembrance of Tony Major! Indeed, Tony was a “Man for all seasons”! Hofstra gave.this gentle man an opportunity to discover who he was and to develop his innate talents! Tony took advantage of all that Hofstra had to offer, from the arts to the athletic field. Against all odds,, Tony succeeded at everything he put his mind to. Needless to say, it was not easy for a young black man in the early 1960’s to make his mark in an unenlightened society! 6/8/2019 03:23:22 pm

George, another moving tribute about someone from your seemingly infinite reservoir of exceptional people.

Altenir Silva

6/8/2019 06:56:08 pm

Dear George,

bruce

6/9/2019 10:48:42 am

george, Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|