|

Some colleges have their priorities straight during this time of Covid-19.

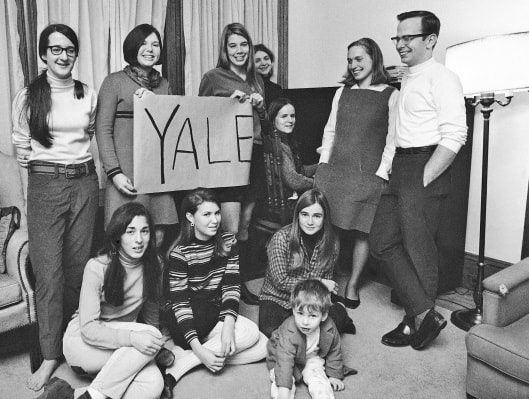

Four schools I already admired – Bowdoin, Morehouse, Sarah Lawrence and Swarthmore -- showed their values in recent days by cancelling all or part of their autumn athletic programs, so they could concentrate on education. Imagine. These schools do not exist to present extravaganza football games every Saturday during the fall semester, for the benefit of boosters and TV networks, to churn up money to keep the whole monstrosity going. However: each decision to cancel caused terrible pain to the people who mattered the most – the student-athletes who will not get to compete this fall, practice with their teammates, perform in front of vociferous family members and loyal fans. You cannot red-shirt a virus-cancelled season, say “come back for a fifth year.” Plus, these student-athletes have futures, although the 2020 fall season will not be part of them. We take it personally in our family. Our grand-daughter, Lulu Wilson, is a loyal member of the Swarthmore women’s soccer team that reached the Division III tournament in her first two seasons. She played very little in her first year due to an eye condition following a concussion, but she played some in her sophomore year - - and every time I checked in on her she raved about her teammates and her coaches and the practices and the togetherness. In between, she pursues a pre-med program, having already spent compelling days in hospitals, gowned up, watching the routines and even the operations. She is all in. When Swarthmore cancelled all fall sports, I checked in on Lulu and asked how she felt about the decision. “Honestly, I think it is smart of Swat,” she texted, using the nickname for the school, “and I admire that they are trying to keep us safe and move our country towards an end. “I think it would be ignorant of them to let us play,” she added. “I look at these big schools going back full-force and I worry that these kids are going to cause outbreaks and keep the pandemic going for the country as a whole. "So I respect what they did,” she said, adding her opinion that “online learning is not the same as a true Swat experience.” Now she is in mourning for what will always be lost – an autumn of practices in the drizzle and gathering darkness, the bus rides around the Northeast, and the identifiable voices of parents who travel from around the country to cheer for Swat. (Intro to Div III: in 2018, after Swarthmore lost to Middlebury in the Round of 16 up in Vermont, on the long bus ride back to Philadelphia, many of the players started studying for final exams coming up, she told me then.) “These four years are really special for us to be together as a team so this time apart will be hard," Lulu said Thursday. "We will have to find ways to stick together and find the positives in this situation.” Swarthmore student-athletes are not alone. I had a premonition a few days ago when I read that Bowdoin had cancelled fall sports. My wife and I have fallen in love with the college in Brunswick, Maine, from visiting the area in recent years, and we always find time to visit the jewel of an art museum on the campus. I also admired the decision by Morehouse in Atlanta to cancel football this year. I have become a fan of Morehouse over the years because of alumni like Martin Luther King, Jr., Donn Clendenon of the 1969 Mets, my Brooklyn hero Spike Lee, and Terrance McKnight, knowledgeable host of a nightly show on WQXR-FM, the classical station in New York. And Sarah Lawrence, in Bronxville, just above New York, is where we were lucky enough to send our two daughters, who gained great educations and eclectic talented friends. The other day, SLC cancelled all autumn sports. All schools are wrestling with terrible choices in this time of the virus. There are no easy answers, but these four admirable schools examined their values and realized sports were expendable – nevertheless, leaving a gigantic loss for a young student who loves her sport, her team, and also her education. ### I just read a powerful book about the first class of women at Yale University – in the fall semester of 1969.

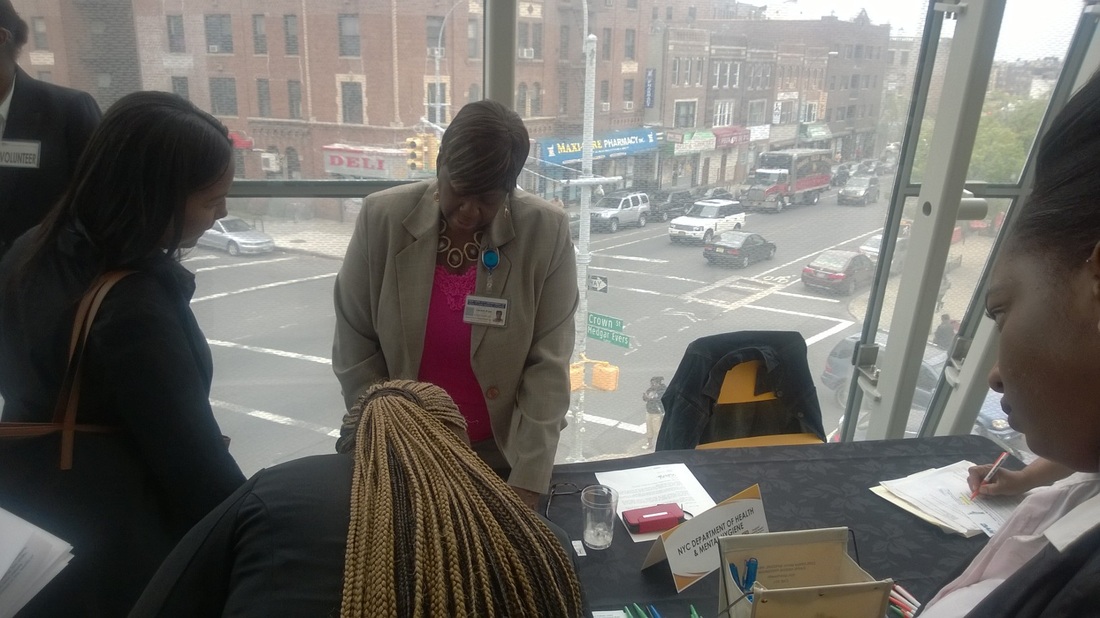

Yale, bless its crusty old heart, managed to enroll female students who were more than up to the academics of the great university, but also quite able to speak up – and act up -- for their rights. It was the 60’s, after all. That tumultuous year of 1969 is the backdrop for the book, “Yale Needs Women: How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant,” by Anne Gardiner Perkins, who arrived at Yale eight years after the first female undergraduates. After years of pressure, Yale finally joined many all-male schools that had accepted women, however imperfectly. Given the limit of 230 spots for women (along with the usual 1,000 spots for male freshmen, all regarded as “leaders”) the admissions department did a fine job, finding women with talent and guts to go along with the brains. Many pioneers depicted in the book do not come off as stereotypical silver-spoon, prep-school graduates but rather the best and brightest from all over – rock stars in their way, with the spirit of Tina Turner and Grace Slick and other icons. In Perkins’ book, these women are as diverse as any admissions director would dream: Among my favorites are Connie Royster, boarding-school grad, actor, African-American, worldly, teaching her instant good friend, Betty Spahn, white, from the Midwest, how to handle chopsticks; Kit McClure, from a New Jersey suburb, talking her way into playing her trombone on the all-male marching band, later cutting much of her red hair and helping form a rock band with a powerful feminist soul. Another pioneer was Lawrie Mifflin, who forced Yale to start a field hockey team – with real uniforms! with a real field! With a real coach! Lawrie became a journalist after shaming the all-male Yale Daily News into covering female sports. She later became a deputy sports editor at the Times -- and a good friend of mine -- and is today the managing editor of “The Hechinger Report” and was recently honored by Yale for her many accomplishments. Not all the women were activists at heart, but most were pushed into action by conditions: no locks in the bathrooms, not enough security at the dorms or around the campus, hardly any female teachers or administrators, and the feeling of being patronized in the classroom while also being hustled for dates (and more) by male students -- and male teachers. (The university still bussed in women from all-female schools, a long tradition.) Fortunately, the women had a champion in Elga Wasserman, with a doctorate in chemistry, who was appointed a sort of dean of women – but without the title, without the power. Wasserman fought for the women, minute by minute, but was eventually seen as a problem by the patrician president, Kingman Brewster, Jr. Two other heroes were a couple, Philip and Lorna Sarrel, he a gynecologist, she a pediatric social worker, who worked as a team to offer medical services and counseling, so much in demand that their one lecture class on sexuality was attended by over 1,000 students – women and men. Facing difficulties they probably could not have imagined, the women demonstrated, infiltrating clubby bastions, making the establishment aware of how things worked, and did not work. There was pain, including at least two rapes of women in the freshman class. Within the four years of their entry, the women had lobbied for more spots, challenging the quota of 1,000 male “leaders” who were accepted annually. Eventually, they achieved gender-free admissions, to the point of numerical equality today. Yale, being Yale, could attract these women -- and diverse men -- of excellence. On campus during the first four years of the pioneers were such future leaders as Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Janet L. Yellen, Kurt L. Schmoke and – sound the trumpets! -- from my old school, Jamaica High in Queens – Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, in her 13th term, now from Houston. Perkins has written a gripping guide on how to seek change in today’s world – as young people realize that our “leaders” are “leading” the U.S. in an assault on democracy and law, prejudices are seeping back, and young people face a future on a smoldering planet. The women of 1969 are admirable role models for all. * * * I mentioned the Yale book to my kid brother, Christopher Vecsey, a professor at Colgate University, which went coed a year after Yale did. Chris (he never tells me anything!) said Colgate held a symposium last April: “Women and Religion, Philosophy and Feminism,” featuring pioneers of 1970. Chris is also the editor of a book from the symposium: https://www.colgate.edu/news/stories/symposium-honors-professors-wanda-warren-berry-and-marilyn-thie * * * NYT review: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/13/books/review/yale-needs-women-anne-gardiner-perkins.html?searchResultPosition=1#commentsContainer NYT retrospective this fall: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/upshot/yale-first-women-discrimination.html I spent a lovely day in Brooklyn on Wednesday. As soon as Mike From Whitestone turned downhill, I felt the surging image of Duke Snider slugging the ball over the screen and into Bedford Ave.

Mike parked near McKeever Pl. and I could feel my head swiveling like a compass needle to the apartment buildings where Ebbets Field used to be. But I was the only person talking about the Brooklyn Dodgers, about ancient history. The occasion was a career expo at Medgar Evers College, where several hundred very qualified students were seeking leads on jobs, on futures. I heard about the expo through Monica and Miguel Mancebo of Selective Corporate Internship Program (SCIP), which does such a fine job of preparing young people for the job market. The students saw my soccer book on the table and wanted to talk about their sport. One young woman from Trinidad plays defender for the Medgar Evers team; another young woman roots for VfB Stuttgart, from her home town; a volunteer told me she roots for Barça and her husband roots for Real Madrid. And Michael Flanigan, the director of development and major gifts officer at Medgar Evers, told me how he referees soccer matches in his spare time. I marveled at the résumés of the Medgar Evers students, their life stories, their work experience. Many of them have worked in kitchens, in day-care centers, in nursing homes. They see it as paying their bills. I told them to be proud of their work; they were learning the process, the system. Many of them want to be doctors and teachers, accountants and, good grief, journalists. I wanted to hire them all. I hope by now somebody has. The Feb. 6 issue of the New Yorker (the normal three days late) contained the sad and gripping tale of the college student, Tyler Clementi, who committed suicide last September after being tormented over his liaison with a man. The excellent article (“The Story of a Suicide”) by Ian Parker clears up a lot of bad information that had been going around. Clementi and his roommate were thrown together for only a few days, long enough to propel him off the George Washington Bridge. I was struck by two factors of this modern tragedy – one about the flaws in dormitory policies, one about how far bullying has advanced with modern technology. College life comes off as Lord of the Flies, with electronics. The young man, a violinist, had just come out to his parents, leaving inevitably jangled emotions. Then he went away to Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey, but it could have been anywhere. The article makes a good case for commuting to college, at least for the first few years. The system of matching up two strangers to live in a closet with beds and desks seems to be an experiment in abnormal psychology. Four roommates might be better than two – somebody just might exert leadership, compassion, know limits to cruelty. Never having lived in a college dorm (I went from commuting to renting a crummy room near school to bunking in with my wife), I cannot imagine the thwarting of creativity, of privacy, in such close quarters. I know, millions of students go through it, what’s the alternative, but it seems like a Petri dish for breeding bad vibrations. If some psych lab had been peeking in on these ill-matched roommates, I wouldn’t have been surprised. Instead, a whole cyber-dorm of unformed children was essentially peeking in. We all know how cruel the human race can be. (Let he who is without sin, etc.) It is tempting enough to taunt the other, even without contemporary toys. But electronic spy equipment in the hands of 18-year-olds, away from home for the first time, is downright dangerous. Clementi, just discovering his sexuality, arranged a tryst, asking his new untrustworthy blowhard roommate to clear out for a few hours, as millions of college students surely have done. In time, he might have been able to shrug off the notoriety or learn to be discreet. The realization that he had been observed put the young man on a bridge. Nobody showed rudimentary conscience until it was too late. The author shows how the legal system seems unclear about just what crime was committed. We all know the cruelty of the tweet, the viciousness of the email. The escalation of the electronic toys race should make any adult shudder while sending children off to college. *A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall -- Bob Dylan |

Categories

All

|