|

When I was in Cuba in 1991, aging baseball fans asked about the old Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox.

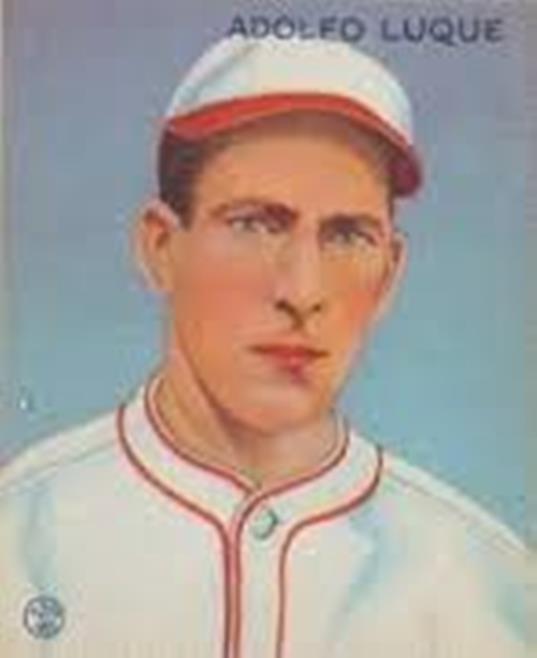

How was Bob Feller? How was Al Lopez? They were polishing ancient memories the way they maintained vintage 1950’s cars. They loved the game itself, debated the strategy of their national teams, held on to the history of the old banished professional clubs like Almendares of Havana. This was their national sport, brought there in the 1860’s by Cubans named Guillo who had worked in Mobile, Ala., and nourished by Esteban Bellan who played for Fordham University and the old professional Troy Haymakers. Later, Americans came for the Spanish-American War and played baseball in their leisure time. Baseball is now part of the patrimony. In the inescapable age of the Web and videos, information crackling over the narrow sea between Florida and Cuba, fans know that Yasiel Puig and Aroldis Chapman have made it big in the major leagues. Is there more where they came from? This is the first question people ask of a sports columnist who went to Cuba for the 1991 Pan-American Games and has kept up on it ever since. Perhaps the national baseball treasures would be the most desired product in Cuba (although, as Rachel Maddow pointed out, Cuban-trained ballet dancers are in demand all over the U.S.) The level of potential major-league talent may be very thin. Plus, it’s really not important. What matters is that Cubans have been starved by the block-headed policies of Fidel and the follies of American leaders. Now President Obama is bringing rationality to half a century of mutual apartheid. Cubans have been living in many forms of poverty. I got the feel in 1991, including a trip to the Bay of Pigs. *- I discovered I could buy items like shampoo – shampoo! – in a dollar store to which I had access because of my journalist credential for the Pan-American Games. *- A well-placed Cuban, volunteering as a journalistic resource, admitted to not minding a hot shower in a hotel. *- Our interpreter, who spoke perfect English, had to wait for two straggling buses to get home after a 12-hour day. We had to persuade her to take a cab we provided. My talented new friends were strangers in their own land. Never underestimate the anger in the aging Cuban-Americans, who lost so much. But life goes on. Surely, there are more players like Minnie Miñoso and Tony Pérez in Cuba. But more important, there are people who need nourishment and work and hope. And shampoo. And visas to travel across the narrow sea -- not in a flimsy boat like Orlando Hernandez, El Duque, but in something safe. Baseball is the least of it.

Douglas Logan y Gonzales de Mendoza

12/18/2014 04:36:59 am

Vecsey, you're an honorary Cuban! It's a state of mind [or soul]. This move by Obama is one of his best. For too long we have been suffering at the hands of the bozos on both sides of the Straits of Florida. Soon my kids will be able to visit their ancestral land the same way the Vietnamese boat people can. Palabras honorosas.

George Vecsey

12/18/2014 07:01:03 am

Gracias, Sr. Me gustaría volver pronto. GV 12/18/2014 07:18:21 am

George,

George Vecsey

12/21/2014 12:18:55 am

John, I am honored that you found my site. How are you doing setting up yours? 12/24/2014 06:16:29 am

George Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|