|

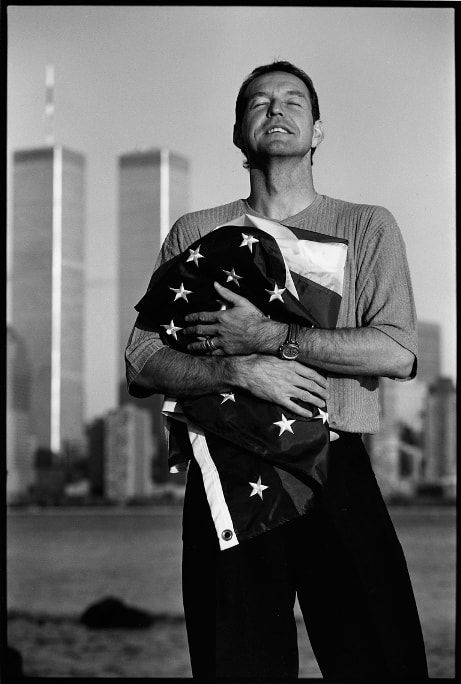

The memories begin with what the World Trade Center meant to people. My friend John McDermott, master photographer, was working on a book in September of 2000, about the 10 most significant people in U.S. soccer in the 1990's.  Thomas Dooley, American soccer captain, born in Germany. Photo by John McDermott, September, 2000. https://www.mcdfoto.com/ Thomas Dooley, American soccer captain, born in Germany. Photo by John McDermott, September, 2000. https://www.mcdfoto.com/ "One of those was German-born Thomas Dooley, son of a U.S. soldier and a German mother and Captain of the US National Team," McDermott wrote me on Wednesday. "Thomas was already a friend, and someone I admired a lot. So for us it was also a chance to catch up and spend a fun day together. I had the idea to make the portrait about 'Thomas Dooley’s American Dream.' His story is actually pretty incredible, but for another day. I had bought an American flag and convinced him that we could do something memorable with him and the Manhattan skyline. He embraced the idea and the result you see here. It’s one of my favorite portaits. "A year later, on September 11th, our lives changed forever.," McDermott continued. "And I thought back to the day I had spent with Thomas. The morning of September 12th my phone rang. It was Thomas. He wanted to tell me how much that picture now meant to him, that he had always liked it, but that now it had special meaning for him. We talked for a long time and, as I recall, probably also shed a few tears over what had happened. And we remembered that beautiful, warm and sunny day a year earlier. My September 11th memory...Never forget." Grazie, John, for pointing out what those buildings meant, at the tip of the glittering island. I had forgotten that my family held a retirement lunch for my dad in the sky-high restaurant. And I had forgotten that I took two French friends, grandmother and grandson, Simone and David, for a drink one evening with a view of the harbor. The World Trade Center meant New York, meant America, meant a place of hope, like the lady in the harbor. And that brings me to my first version, published on Wednesday: In August of 2001, I covered a rehab start by El Duque Hernandez in Staten Island. On the ferry back, I chatted with some visitors from Spain and asked what they were doing next. They pointed at two giant buildings glowing into the night, at the tip of Manhattan.

“Es para turistas,” I said with a smile, about the newcomers on our skyline. “Somos turistas,” one man said with a smile, giving it back. * * * I think about it every year. Our son was working in a newsroom in Atlanta and called us just before 9 AM. Don’t go into the city, he told me. A plane had hit the World Trade Center. We discussed whether it was big or small, while I flicked on the television. Within a few minutes, I saw a blip across the sky, and we knew it was no accident. * * * There was news of a hijacked plane, missing over Pennsylvania. My wife and I thought of our first grand-child near the Susquehanna, and we quivered in fear. When we heard the plane had gone down further west, we felt horror and, I admit, relief. * * * After gaping at the tube, I called the office. Mr. Bill and I agreed that there was nothing a sports column could say that day. Life would go on? Save that for a day or seven. Safe in the suburbs, I watched, wondering who I knew worked down there. * * * As it turns out, there were connections -- tragic and escapes. A man one of my relatives had baby-sat for, decades earlier. The sister of a colleague, who stayed in her upper-floor office to be with a friend, who used a wheelchair. People in neighboring towns, whose cars remained in railroad parking lots, mute memorials to their vanished drivers. A relative had dropped her laundry at the cleaners in the World Trade Center, and walked home. A friend voted in a primary and was late for work downtown. A journalist friend was supposed to catch one of those flights but after two hectic weeks at the US Open, she chose to sleep in. Soon we got to know thousands who were there, and are still there. * * * Having covered police and fire officers as a news reporter, I knew what they did, rushing into danger, the opposite way of the crowds. I had written about cop funerals, firefighter funerals, and now there would be hundreds. * * * Two days later, the winds picked up. I went out for the morning paper and our cars were covered with gray ash, a dismal snowfall, 25 miles from Ground Zero. The air was vicious. * * * I received e-mails from friends all over the world: Japan, Mexico, Europe, Australia, wanting to know if we were all right. Nowadays, when earthquakes or floods or fires or massacres strike, I write to Osaka or Mexico City or Paris because I remember. * * * My work resumed. I wrote about the impact sports have made in wartime, national-tragedy time – how sport can be a diversion, a statement, a rallying point. It was hard to type these words, but I had to believe that life would resume. * * * I went out to lunch with my friend Logan in midtown. Food tasted good, people were dressed, but the mood was somber. People told us about what they had seen from office windows, apartments, rooftops. Every bite, every word, was like play-acting. * * * That night, I wanted to see. I took the subway downtown and used my police press card to get inside the first security barrier, but was stopped at the real barricade, as well I should have been. I watched the scene from hell, as people and machines labored in the smoke and the shadows. After 15 minutes, I realized my throat was scratchy and I felt sick. I bought a cup of black coffee just to clear the taste in my mouth, and took the subway back uptown, in terror. In the subway car, every suitcase, every gym bag, was a potential bomb. * * * In those days, federal and city officials assured everybody, including the cleanup workers, that the air was perfectly safe. These wilful ignoramuses were like doctors back in Appalachia, who told the miners, “Hell, son, that coal dust will cure the common cold.” * * * I was assigned to cover the first ball game back, the Mets at Pittsburgh. We were not ready to fly, so we drove due west. The September air was crisp and clear. I love that ball park at the confluence of the Allegheny and the Monongahela, with the Roberto Clemente Bridge and the view of downtown, but I was in terror as I worked. Every noise made me jerk my head skyward, expecting to see a rogue airplane, a monstrous blip. * * * I think about those who were captives, and those who ran to danger. My experiences and reflections seem peripheral, then and now. 9/11/2019 05:01:33 pm

I never felt that Mayor Rudy Giuliani was good for the city. His behavior after 9/11 and ever since has confirmed this.

Ed Martin

9/11/2019 06:18:50 pm

It seems strange to thank you, George, for writing this piece, but I think your human experiences and feelings add an important dimension to the public story.

Roy Edelsack

9/11/2019 09:41:00 pm

-On September 9, 2001, Leyton Hewitt beat Pete Sampras to win the

Mike from Whitestone

9/11/2019 11:44:06 pm

I agree with Ed in the sense of thanking you GV for this piece on such a somber topic but, as is always the case, your insight, points and sharing put a unique perspective on any topic. You know where I work, that same smoke and ash wafted its way into the building....sad. We did our part there and in NJ, getting the printed word to so many, all day, all night........no internet in places, it was our little piece of helping the recovery.

Mendel

9/12/2019 08:37:32 am

I was in a cloistered Jerusalem neighborhood with no internet or television and exactly one English language radio station. Overheard a news broadcast of "a plane" hitting the towers in the background of a phone conversation with a friend in Queens. Panic in the voice of family members in NYC when finally able to get through. "We can't talk now!" "There might be more planes in the air!" The father of a student in Jerusalem worked at the Pentagon and our student body gathered in the chapel to recite Psalms until we heard that his father was OK. I felt sadness for my city and shame for being so far away.

George Vecsey

9/12/2019 08:57:34 am

Thanks to the first five respondents. My comments:

bruce

9/12/2019 09:05:48 pm

george, Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|