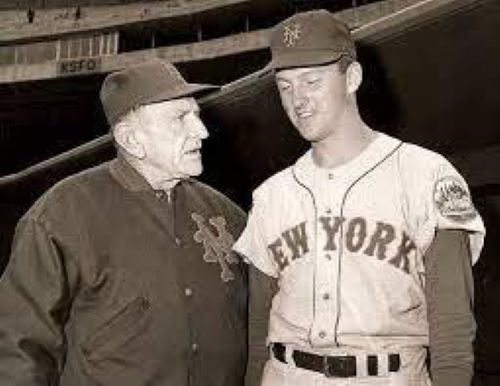

Casey Stengel and Bill Wakefield, 1964. Casey Stengel and Bill Wakefield, 1964. Fifty-seven years go fast. I was listening to the Mets’ game the other night, when a sturdy young pitcher named Tylor Megill gave up a grand-slam homer to the fourth batter in the first inning. Four up, four in. Suddenly, the Mets’ broadcaster was talking about first-inning grand-slam homers, and I heard the name of Bill Wakefield, now an email pal, but in 1964 a rookie pitcher out of Stanford, enjoying the heck out of the one year he would have in the major leagues. That year, Wakefield also gave up a grand-slam -- to Ed Bailey of the Milwaukee Braves. I told my (long-suffering) wife that a friend of mine just had his name called out on the Mets’ radio broadcast – 57 years after the deed was done. “What is it like for a ball player to be remembered for something, that long ago?” my wife asked. Well, I said, there was Ralph Branca, a good guy who gave up a homer to Bobby Thomson,also a good guy, in 1951. And I thought of other ball players who had one really bad moment that never went away. But Bailey’s grand-slam off Wakefield was hardly historic – just rare enough to pop up 57 years later. I shipped off an email to Wakefield, out in the Bay Area. How did he take being back “in the news” again? “I'll have a glass of Chardonnay,” he replied, “and/but, yes I remember it well. “I always admired the guys who answered the tough questions -- and didn't duck out early. “Sure go ahead,” Wakefield answered in two separate emails. “The only downside to telling the old stories is the rolling of the eyes and the ‘Dad, you think you've milked a modest career about long enough?’” from son Ed, 33, D1 pitcher at Portland Pilots and daughter Laura, 31, softball at Boise State!” Then Bill Wakefield, just turned 80, successful businessman, frequent e-mail correspondent, pulled out all the details that many athletes store in their competitive brains.(I’ve heard Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova discuss their epic matches, stroke by stroke.) For Bill Wakefield, it was yesterday: “ 1964 -- We're flying to Milwaukee last road trip of the year. I'm feeling pretty good for a rookie -- lot of games -- 60++++ - pretty good ERA (low 3's!!!) -- 3 – 4, not bad for Mets of that era. On the plane, Mel Harder comes to me – ‘Hey Billy - I know you've been in a lot of games but....’.” (Mel Harder, then nearly 55, had pitched 20 seasons with one team, Cleveland, and was a respected pitching coach with the Mets that year.) “Casey wants to save our starters for the Cardinals in St Louis, ‘cause they‘re in a pennant race," Wakefield recalled Harder telling him. “We're gonna start you on Thursday in Milwaukee! OK?” “Me ---What am I gonna say -- ‘Hey Mel the arm’s a little on the tired side?’ Tell Casey no? “So I say, ‘I'll be ready.’” The game was on Oct. 1, 1964. Wakefield recalls Hot Rod Kanehl, the utility player who shepherded him around the majors for one memorable season, coming up to him: “‘Hey, they're not playing Aaron today.’ So it turns out -- so what !!!! the other guys did pretty well"!!!! Wakefield added: “Hot Rod sees there are 3,000 people in the stands - at best -- and tells me - "Well kid at least a big crowd won't make you nervous.!" Ball-player gallows humor. Nervous or just arm-weary, Wakefield gave up singles to Rico Carty and Lee Maye. Felipe Alou was up next. “In that era, first inning, no outs, runners on first and second, 99% of the time the guy bunts the runners over to second and third. I'm thinking, cover third base line, field the bunt, throw to Charlie Smith at third and get the force. Get the out. “Alou hits the first pitch, one-hopper back to me - the obvious play is double play -- throw to second. I throw to third for the force -- Charlie Smith is standing, looking at second with his hands on his hips -- almost hit him between the eyes -- he drops the ball, bases drunk, I'm in trouble!!! “Rookies get in trouble and they try to throw a fast ball harder and get an out. Veterans throw softer and get a ground ball. Bailey -- first pitch -- I'm thinking two-seam fastball outside, he tries to pull it, ground ball to McMillan, and out of trouble. “It catches too much of the plate -- he goes to opposite field and hits a home run.” Wakefield fast-forwarded to the third inning. “Still a rookie. I'm still in there having trouble -- Walk Carty -- Casey comes out - Rookie question from me – ‘You taking me out because I walked Carty?’ Casey kind of has a quizzical look on his face -- and a smile and says ‘No, I'm taking you out because you've given up 7 runs!!!” Mets lost. “No excuses -- they hit the ball.” More memories: “I'm shaving after the game -- cut my chin - baseball humor -- Jack Fisher: ‘Did you try to cut your throat?’ I laughed." Then Wakefield recalled Joe Gallagher, the Mets’ TV producer, on the Mets’ charter flight that night, to St. Louis: “I said, did you lose some of your audience after the first three innings?” The Mets scared the Cardinals on that last chilly weekend, and Wakefield’s memories come pouring out: “On to St Louis -- Chase hotel -- Gaslight Square ( Hot Rod and I didn't know it -- but it would be our last visit to Gaslight Square!!) Hotel swimming pool stories - old classic hotel. Harry Caray's hang-out hotel. Casey late night in the lobby entertaining!! Westrum laughing at Casey's stories. Lou Niss smoking and watching. Whiskey-slick players file into the single lobby elevator!” My memories jog totally with Wakefield’s. The Chase-Park Plaza was also my favorite hotel on the road. The games were epic, too. “Give 'em a scare,” Wakefield recalled. The gallant original Met, Alvin Jackson, beat Bob Gibson on Friday, and the Mets won again on Saturday. Wakefield pitched in relief on Sunday and so did Gibson, to save the Cardinals’ season. The Cardinals went on to beat the Yankees in the World Series. Kanehl and Wakefield, Butch and Sundance, never played in the majors again, and remained pals until Hot Rod’s death in 2004. “I could have used a few more pitches to be a starter!! Relief -- sinker/slider, OK. Starter needs 4-5 pitches. “ He can pull up the memories of his short career: “The Milwaukee game -- I would paint a different picture if I could. There were 60 other games I would rather recall!! But that's the way it is!” Then Wakefield added: “As long as we're telling stories from 57 years ago -- who's gonna correct me??? -- make sure you also point out that I got Yogi Berra to ground into a double play in the Mayor' s Trophy Game in front of 55,000. Big deal in the era of no interleague play!!” As I told my wife, Bill Wakefield pitched a season in the major leagues, and that is something, ### My thanks to Marianne Vecsey for jogging some grand old memories. The grand-slam game, courtesy of the great website, retrosheet.org: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1964/B10010MLN1964.htm Bill Wakefield’s career, courtesy of the other great website: https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/wakefbi01.shtml Colin Phelan is 23, a writer and teacher in Massachusetts, a recipient of a Fulbright-Nehru scholarship to India next year, and a friend of a family close to us. Our friend raved about his website, so I volunteered to take a look and was knocked over by what he knows, what he cares about. Back home in the States during the pandemic, Phelan has not lacked for adventures – taking his bike across country, going into Great Sand Dunes National Park in Colorado as fearsome sand tornadoes swirled ominously ahead, and so on. Passing through St. Louis, he discovered a World Chess Hall of Fame – who knew? -- and perhaps because he gets hammered by his students in their early teens, he explored the museum. Of course, he did. The exhibits fascinated Phelan with the various themes of chess sets around the world, and he also began to understand the role India played in the worldwide popularity of chess.  Phelan's blog also links warfare and chess, comparing the chess tactic of dominating the flank to one of the key moves of the Battle of Gettysburg, on July 2, 1863 -- how a professor from Bowdoin College in Maine, Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, told his troops to fix bayonets and rush downhill, into what became the gruesome but decisive Battle of Little Round Top. (Phelan caught my interest because, in my three years of college ROTC, Gettysburg was still being used as a key lesson in battlefield tactics, now of course outmoded, but still an object lesson in planning and reacting. I have walked the battlefield with our grandson George, who lives not far away. I recommended that Phelan read the magnificent restored first section of the novel, “O Lost,” by Thomas Wolfe, which takes place north of Gettysburg, a few days before the battle.)  Anthony Bourdain after dining with President Obama at Bun Cha Huong Lien in Hanoi, May 23, 2016. Anthony Bourdain after dining with President Obama at Bun Cha Huong Lien in Hanoi, May 23, 2016. Phelan has done most of the teaching in our interchange. His blog includes copious photos of chess sets from around the world – including a fruit-and-vegetable set – as he veers into an appreciation of Anthony Bourdain’s lust for life: “As a devotee to Anthony Bourdain’s ability to discover culture and companionship through food, I’ve for long tried to discover another means through which people wedged apart by language or other barriers can not only coexist, but catch glimpses of another’s personality and being,” Phelan wrote. I would not have expected poor Bourdain to pop up in a riff on chess, but there he is. Colin Phelan is living at a fast clip, so many interests and observations and opinions. Phelan has already had adventures on his first visit to Kolkata and Delhi, teaching English, learning the local languages. Now he’s back in the States for a school year, having adventures. Nice to be 23. * * * I have not begun to explore all the corners of this website. Please explore and enjoy: https://www.colinephelan.com/post/from-chaturanga-to-chess-successful-cultural-transmission-or-lost-in-translation Bob Gibson passed Friday of pancreatic cancer.

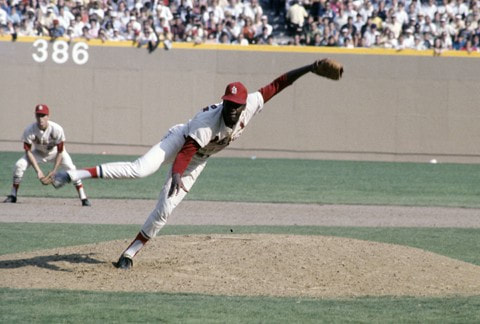

He was one of the most competitive athletes I ever covered – a fierce, purposeful flame. I wrote about Gibson (below) 26 months ago when he disclosed the fearsome diagnosis. I would also recommend today’s obit in the NYT by my friend Rich Goldstein: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/02/sports/baseball/bob-gibson-dies.html Also, you might want to see the piece I did in 2009 when Gibson and Reggie Jackson were promoting a book they had written (with Lonnie Wheeler) about the eternal struggle – that is, between pitchers and hitters. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/30/sports/baseball/30vecsey.html I watched the rivalry play out over a power breakfast in New York, and when I asked a question Gibson considered cheeky, he verbally buzzed me, high and inside. I thought Reggie was going to choke on his oatmeal, or whatever he was eating. His look said: “And you writers think I’m a hard guy.” I consider myself fortunate to have been around Gibson, in the tight little sanctums of the Cardinal clubhouse in the old, old ballpark. That kind of access to athletes is gone during the pandemic, with writers minimally getting sterile, mass interviews with a few principals, and I’m just guessing it never comes back. No writer today will see a star like Gibson, up close, the way I did in the tense last weeks of the 1964 season and World Series. Finally, a word about superstars. My admired colleague Dave Kindred has a mythical mind game called “The Game to Save Humanity,” meaning “we” get to play Martians, or whatever, one game, Pick your team. My pitchers are Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson, lefty and righty, even beyond numbers and longevity, but just, well, just because. I saw them. RIP, Hoot. It was an honor to observe you. From July, 2018: https://www.georgevecsey.com/home/dont-mess-with-bob-gibson Don’t Mess With Bob Gibson Bob Gibson is fighting pancreatic cancer – “fighting” being the operative word. Everybody knows Gibson’s combative pose as the best right-handed pitcher in the universe, starting in 1964. I was lucky enough to be present when Gibson morphed from very good pitcher to legend, in 22 epic days at the end of that season. He had been underestimated by his first manager, Solly Hemus, who had lost his black players by using a racial taunt to taunt an opponent in 1960. Gibson was still very much a work in progress after Hemus was canned in 1961, and replaced by Johnny Keane, who reminded me of the kindly commanding officer, Col., Potter, in the classic series, “M*A*S*H.” After mid-season of 1964, Gibson pitched eight straight complete games – a statistic that probably would default the computers of today’s analytics gurus. Yes, really good pitchers really did finish a lot of games. As the Phillies started to fold, the Cardinals and Reds put on a run. On Sept. 24, Gibson lost a complete game in Pittsburgh. On Sept. 28, he beat the Phillies, going 8 innings. On Oct. 2, with the Cardinals in first place on the last Friday of the season, Gibson lost, 1-0, to the lowly Mets as Alvin Jackson pitched the game of his life. Then on a very nervous Oct. 4, Gibson pitched 4 innings in relief, gave up two runs, but was the winning pitcher, as the Cardinals won their first pennant since 1946. I can still see him on the stairs to the players-only loft. “Hoot, how’s your arm?” a reporter asked. “Horseshit!” Gibson said. Then he was gone, up the stairs. When Manager Keane gave his pennant-winning media conference, somebody asked why he went so often with a certifiably fatigued pitcher. “I had a commitment to his heart,” Keane said softly. Those words gave me a chill as Keane spoke them; they remain one of the great tributes I have ever heard from a manager of coach about a player. Keane’s faith, his shrewd understanding of the man, helped Gibson demolish the stereotype that many black players had to overcome. Gibson then started the second game (8 innings, lost to Jim Bouton), won the fifth game in 10 innings) and the seventh game in 9 innings to won the World Series. He had pitched 56 innings in 22 days, become a superstar after some delay, just as Sandy Koufax had done earlier. In over 70 years as fan and reporter, I will take the two of them over any lefty-righty pair you want to pick. Gibson never put away his testy edge. He was rough on rookies, rough on how own catchers and pitching who trudged out to the mound to counsel him. “You don’t know anything about pitching, except you can’t hit it,” he told Tim McCarver, who has relished that taunt ever since.) He did not observe the fraternity of ball players, even chatty types like Ron Fairly of the Dodgers. One time Fairly stroked a couple of hits off Gibson, who then hit a single of his own. But Fairly made the mistake of engaging Gibson in a collegial way. I always heard that Fairly praised Gibson for his base hit, but Gibson insisted that Fairly had raved about Gibson’s stuff and wondered how he had possibly made two hits off him. Either way, Gibson glared at Fairly. Didn’t say a word. Next time up, Fairly observed Gibson, glowing on the mound, and mused to the catcher, Joe Torre, that he did not think he was going to enjoy this at-bat, was he? Torre wasn’t going to lie about it; he just smiled as Fairly took one in the ribs. That is Gibson. Don’t mess with him. Torre later brought Gibson to the Mets as his “attitude coach,” as if you can coach attitude. Gibson remains competitive. A decade or so ago, he and Reggie Jackson collaborated on a nice book about the age-old yin/yang of pitcher/hitter. They met me for a power breakfast in New York to discuss their book, and it went fine until near the end. Working on a book on Stan Musial, I asked Gibson if I could ask one question about Stan the Man. “Absolutely not,” Gibson snapped. He and Musial had the same agent, and he knew that Musial had put out a fatwa against friends and family discussing him with writers. Gibson’s abruptness caused Reggie to nearly choke on his bagel as he tried not to laugh. Classic Gibson. This is the guy who is going to fight a formidable disease. Knock it on its ass, Hoot. * * * (Below: video of Christopher Russo interviewing Gibson (Reggie in background) about the friendly little incident with Fairly, back in the day.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wF1NCyYg0T8 https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/g/gibsobo01.shtml You’ve heard of Men in Blazers? Get ready for (what I like to call) Men in Shorts, talking footy from a suburban patio on a Sunday morning. My St. Louis pal Tom Schwarz is part of an eclectic group of soccer buffs who emit the weekly show, captured as it happens and sent out through the mysteries of Youtube and Facebook. The merrie bande called me Sunday, July 5, and we talked about survival during the bungled pandemic, viewing “Hamilton” on the tube, live sports in empty stadiums. I am heard from Minute 30, as long as they can carry me. The show is “live” on Facebook, so I am told, but later put together for Youtube. They occasionally get a real soccer person, like Taylor Twellman of St. Louis, ace scorer now ace broadcaster, on Jan. 20, 2019. Cast members include: Edmundo (Gail Edmunds, plus guitar). Ted Williams, not the frozen one, women’s soccer authority and show producer. Josh McGehee, Bradley Univ., 2018, labelled “our resident soccer expert” (every show needs one.) Russell Blyth, St. Louis Univ., Dept. of Mathematics, “native of New Zealand” (you can hear it), reads the scores of Sunday matches in “traditional BBC fashion,” lover of tango and Liverpool fan. Patio Host Tom Schwarz, seller of plants, world traveler, family guy, outside gunner in basketball, and master salesman who once hawked 175 copies of my Stan Musial biography in soccer pub in one night. The lads are gearing up their act for the arrival of a St. Louis club in Major League Soccer in the 2022 season, an honor for one of America’s best nurturing cities for the sport. Meantime: socially distanced. (My old photo vanishes by pushing the video arrow, I hope.) I didn’t remember, until a nice guy named Bob sent me a link that noted the 75th anniversary of Stan Musial’s first game, Sept. 17, 1941.

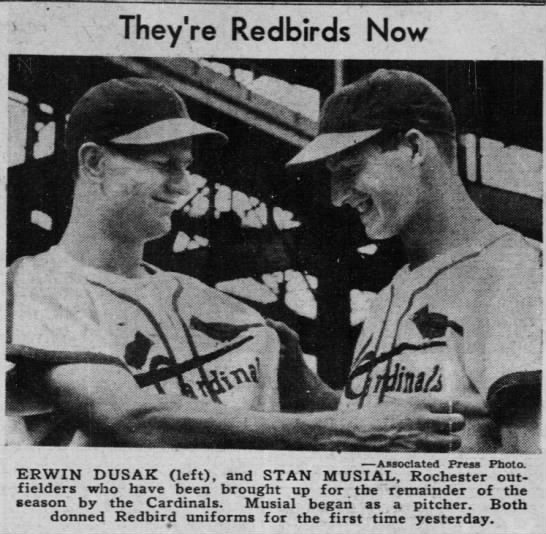

This reminded me that baseball -- for all the steroids and designated hitters and the deafening blare of ball-park commercials – is pretty much the same game. Teams battle all season, and then in September new boys come along to alter the pennant race. You never know. In New York this week, the Mets won a game because an obscure callup named T.J. Rivera, out of the Bronx, hit a home run, and the Yankees almost won a game as a recently dismissed hitter named Billy Butler flew across the country to drive in runs in his first game. Shades of Stan Musial, now known as a career .331 hitter but in 1941 not known at all, even in St. Louis. He was just a kid called up from Rochester because a few Cardinals were hurt as the team tried to catch the Brooklyn Dodgers. My Brooklyn Dodgers. I was 2, but I was rooting. Years later, our fans would dub him “Stan the Man.” He moidered us, but we loved him all the same. Nobody knew him when he came up. There was no web-o-sphere, no blab-o-sphere. He just showed up in St. Louis, as ordered, took the uniform No. 6 (he was not a star prospect, but the uniform was available) and in the second game of a doubleheader he tried to hit Jim Tobin, a pitcher known as Abba-Dabba because his knuckleball fluttered with occult mystery. Musial popped up the first time but then calibrated for a double and single and two runs-batted in. The Cardinals didn’t catch the Dodgers, but Musial pretty much hit like that right through 1963. The Boston Braves’ manager, named Charles Dillon Stengel, was so jealous of the new talent that he kept telling people, “They got another one,” or words to that effect. Thus was born one of baseball’s most beautiful bromances, two men who positively adored each other for life, but never got to work together. The Cardinals loved the kid’s swing, and decided they shouldn’t run him out of the batting cage, the way veterans did. On a subsequent train ride, Terry Moore, one of the great baseball captains, sat next to Musial in the parlor car and asked him who he was, and Musial said he was the lefty whom the varsity had bombarded in a spring-camp game. Right, he started the year as a rag-arm pitcher. It’s all in the biography I did about Musial, “Stan Musial, an American Life,” published in 2011. Musial passed in January of 2013 and I wrote about him in the Times -- the 475 homers, the exact same batting average at home and on the road, the friendship with John F. Kennedy, the identification with his hard-times home town, Donora, Pa., and his adopted home of St. Louis, where he could be his aw-shucks self. Players still come up in September and perhaps affect pennant races, but not necessarily anybody quite like Stan the Man. * * * Musial’s first box score: http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1941/B09172SLN1941.htm The link in the web site of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: https://stltoday.newspapers.com/clip/4562936/sept_17_1941_stan_musials_first/ This is an essay I have been dreading since September when Yogi Berra passed and I called up his good friend (and perhaps even his publicist-inventor) Joe Garagiola to see how he was doing.

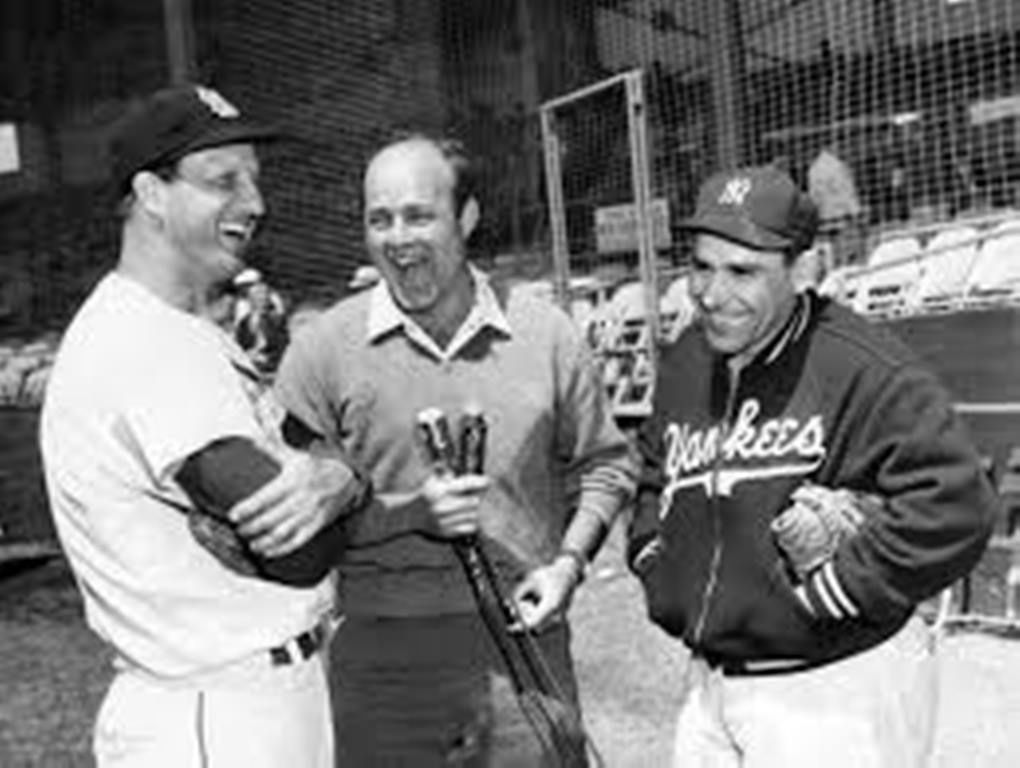

Garagiola, who died Wednesday at 90, always called back, to tell stories, illuminate, maybe even heighten legends. I’ve known about him since the 1946 World Series, when I was 7 and he was a brash 20-year-old rookie for the home-town Cardinals who out-talked the superstars, Stan Musial and Ted Williams. Even the writers of the time, who did not make a practice of working the locker rooms for quotes, could not miss the ebullient kid. And when Garagiola split a finger in the epic seventh game (when Enos Slaughter scored from first on a looped hit to left) Garagiola ran around the Cards’ clubhouse waving his bandaged finger and shouting, “Hey, I’m out for the season! I’m out for the season!” He was rehearsing for his later career as baseball everyman on NBC. You can read two wonderful tributes by Richard Sandomir and by Richard Goldstein in Thursday’s Times. This one is strictly personal. Joe was always a wonderful source – not a social friend but somebody I really liked and trusted. He was fair, even about a broken friendship with Musial. Garagiola even invented himself, including the rep that he was a bad ball player. Fact was, he had been good enough to be stashed by the devious Branch Rickey as an under-age prospect in the Cardinals’ farm system, shining shoes and taking batting practice to evade the scouts until he came of age. Let the record note that Garagiola hit .316 and drove in four runs in the 1946 World Series before, like many catchers, he got hurt. Later he accumulated the insights of a backup catcher, inventing himself – and maybe even his pal, Lawrence Peter Berra, from the Italian neighborhood, The Hill, who signed with the Yankees. Without baseball, they both could have been laboring in the brickworks or producing toasted ravioli on The Hill. Garagiola and Musial used to drive for hours from the St. Louis region, talking to fans for a few bucks. They agreed they both had mike fright. Musial, who was shy and had a bit of a stutter, was afraid they would hand him the microphone. Garagiola was afraid they wouldn’t. Garagiola’s road to the radio booth is well told in the Times. I got to know him in the mid-60’s when he went to work for the miserable Yankees, enlightening spare time by imitating Joe Pepitone’s protests of a called third strike, hairpiece slipping, arms waving. Garagiola gave Pepitone’s gesture an operatic feel, calling it the “Ma Che Fai?” (What are you doing?) Joe was always there for color and background. I once edited a quite lovely anthology called “The Way It Was” about great sports events and I chose the 1946 World Series (which I consider the greatest World Series, ever) for my own chapter. Joe was working for the Today Show, getting up in the dark, but at a more civilized hour he had time for me in his office at NBC. His stories make that chapter hum – the postwar hopefulness, the talent, the veterans, the fun. In his later decades, Garagiola became an even greater man – helping create a charity for destitute players (B.A.T.) and lobbying against chewing tobacco, which had disfigured and killed some players. When I was writing the Stan Musial biography in 2007-8, Joe talked, off the record, about the friendship gone bad over a mutual investment in a bowling alley, run by surrogates. The ultimate headline in the Post-Dispatch was: “Stan and Joe: Business Splits Old Friends.” I don’t believe they ever spoke again. For my Musial biography, Garagiola – way off the record -- told me sweet stories about Musial, their car rides, their early days when it all was good. His loving insights enrich my book. I sent him a copy and one day after a siege of bad health he rang me and, nearly sobbing, thanked me for being fair to him – “and to Stan.” That was Joe Garagiola – emotional, perceptive and fair. When he didn’t call back about Yogi, I knew it was bad. This is a good week to talk soccer, if only to celebrate two World Cup qualifiers in the next week.

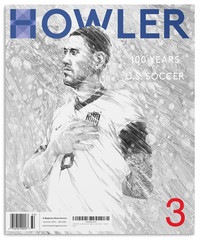

The third edition of Howler Magazine – getting better issue by issue – contains an all-century team picked by Howler contributors and other so-called experts (including me.) The first team, in classic 4-4-2 formation, consists of: Brad Friedel, Steve Cherundolo, Eddie Pope, Alexi Lalas, Carlos Bocanegra; Landon Donovan, Tab Ramos, Claudio Reyna, Clint Dempsey; Eric Wynalda and Brian McBride. The subs are: Kasey Keller, Thomas Dooley, Jeff Agoos, Marcelo Balboa, John Harkes, DaMarcus Beasley, Cobi Jones plus Archie Stark, Billy Gonsalvez and John (Clarkie) Souza, the latter three from well before my memory. The voting was done electronically and I cannot find my worksheet, but I am 95 percent sure this was my team: First team: Keller; Cherundolo, Dooley, Balboa, Beasley; Donovan, Ramos, Reyna, Harkes; Dempsey, McBride. My bench included: Friedel, Pope, Lalas, Michael Bradley, Wynalda, Jones and Harry Keough, the defender on the 1950 U.S. team that stunned England, 1-0, in the World Cup in Brazil. I was blessed to sit next to Keough at lunch in St. Louis in 2010, and I wrote about him when he passed in February of 2012. For me, Keough represents all the stalwarts in the great soccer cities, who played this sport back in the day. One explanation: I included Beasley on the back line because he has saved this current qualifying effort by shifting to left back, and playing the full field, defense to offense. He was one of the young stars on the great 2002 run in the World Cup – and was the 80th-minute sub by Bob Bradley before the desperate 91st-minute goal against Algeria in 2010. He didn’t touch the ball on that run, but his presence was a sign that the U.S. had one run left. He makes everybody better. If I’d waited another month or two, I might have put Jozy Altidore on my bench, too. Readers may choose to comment. The Summer 2013 issue of Howler is devoted to 100 years of U.S. soccer, with features on Jurgen Klinsmann, Michael Bradley and Clint Dempsey, among others. Then there is this story, I never heard before, about a bloke who was abusing Harry Redknapp at West Ham in 1994, only to have Redknapp put him in the match at halftime. The fan then put the ball in the net (but you need to read right down to the last paragraph.) Jeff Maysh finds Steve Davies and tells his weird story. Thanks to Howler for a memorable edition. This is a good week for soccer. I hate that the match at Costa Rica Friday night disappears into a dark hole known as the beIN channel. The Mexico match in Columbus, Ohio, next Tuesday is on ESPN. A good week for soccer. When I was writing about Levon Helm of The Band before his death on Thursday, I referred to the commonality of American and Canadian culture, pertaining to pop music.

I was not saying it all sounds alike, but that modern technology and communications have exposed all of us to various strains of music that we know and love. The Band produced a new blend of rock, folk and country from all over the continent. Levon, bless his heart, brought Arkansas north of the 38th Parallel. When the soul singer pictured above delivered the first note of Let’s Stay Together – the first high note! -- everybody knew he was doing Al Green. Of course, it was at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, and “The Rev” was in the audience, and President Obama quickly made a Sandman joke (Sandman Sims, a noted tap-dancer, used to give performers the hook when the Apollo audience had enough.) Not everybody watching the President got the Sandman reference, but who didn’t recognize Let’s Stay Together? It’s in the culture. I’m an official Old Guy, and my iPod has Brazilian music, Latino Music, the Chieftains, Anna and Kate McGarrigle with Quebec accordions, Joe Williams at Newport, Lucinda Williams, Thomas Hampson singing Stephen Foster. Not one culture, but so many cultures, all out there in our ozone. When the American President can do Al Green, we are getting somewhere. Response to Thoughtful Reader Brian – II The other day I mentioned a double Yankee connection to Stan Musial. This was before I gave a talk about my Musial biography, at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, a lovely building on the Grand Concourse. Brian asked: just what were those connections? Well, in 1938, when Musial was already signed by Branch Rickey’s vast Cardinal farm system, he told a scout from his home-region Pittsburgh Pirates that the Yankee empire was showing an interest in him. Apparently an un-named Yankee “bird dog” had spoken to him, according to a Musial friend who was trying to get the Pirates interested in the local boy. But the Pirates couldn’t touch Musial because he was under contract, and the Cardinals quickly sent him to his first minor-league post in West Virginia, as a wild lefty pitcher. The other Yankee connection? When Musial slumped in 1959 and manager Solly Hemus saw fit to bench him, the Sporting News ran a copyright story that the Cardinals might trade Musial to the Yankees for St. Louis home-boy Yogi Berra. Musial said it was ridiculous, nothing to it. He had already blown away a proposed trade for Robin Roberts a few years earlier. The question is: how would Musial have done as a Yankee, either at the start of his career or at the end? Perhaps he would have gotten lost as a wild young lefty pitcher, and never gotten a chance to show his hitting ability. He only got to play the outfield regularly in the Cardinal chain after blowing out his pitching shoulder while making a diving catch in center field. Years later, the Yankees found a position for a shortstop named Mantle, and they found ways for Berra and Howard to co-exist. My guess is the Yankees – or any club – would have discovered the kid could hit and they could have used him in left field or at first base, just as the Cardinals did. In 1960, the Pirates turned down a chance to get Musial for their pennant drive. Could his bat have helped either the Yankees or the Pirates in that wild World Series? Oh, yes, Musial visited Yankee Stadium in his first two World Series in 1942 and 1943 and he hit his last all-star homer in 1960 in Yankee Stadium. Those are his Bronx connections. With impeccable good sense, Musial managed to spend the last 70 years in a grand baseball city that loves and appreciates him. He did fine. Twice in his long and splendid career, Stan Musial was rumored to be going to the Yankees.

Once was before he was nicknamed Stan the Man in another borough; the other happened when he was Stan the Elder. Of course, Musial became and remained the great sporting figure of St. Louis, a perfect blend of athlete and a grand old baseball town. On Tuesday, April 17, in the Bronx, I will be discussing the Yankee parallels in my biography, Stan Musial: An American Life, published in 2011 by Ballantine/ESPN. The talk will be at 3 PM in the Bronx Museum of the Arts, 165th St. and the Grand Concourse, part of a Yankee-centric spring baseball lecture series organized by Cary Goodman, the executive director of the 161st Street Business Improvement District. It is a formidable lineup that began Sunday with Arlene Howard discussing her memoir of her husband Elston. Today (Monday) is Kostya Kennedy and his book about 1941. And on Wednesday Howard Bryant and Howie Evans will be talking about Henry Aaron. The full lineup is here: http://www.newyorkology.com/archives/2012/04/bronx_museum_ba.php. I will give my theories why it was good for all concerned that Musial did not become a Yankee. Although, can you imagine him hitting to all corners of the old Yankee Stadium? “If you’re in the neighborhood,” as the broadcasters say in the early innings, please come by and say hello on Tuesday. I will always be grateful that Harry Keough came out for lunch last May. He sat next to me in a neighborhood Italian place in St. Louis, wearing a green jacket, the sweetest, friendliest man in the world.

He was soccer royalty. I knew that from his history -- playing fullback the day the United States stunned England, 1-0, in the World Cup in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, June 29, 1950. That amazing accomplishment glowed from him for the rest of his life, which ended on Feb. 7, at the age of 84. There was no need for me to prod Harry to recall the upset because it has been documented in so many books and films and newspaper stories. It was quite good enough to sit around a raucous table in what just might be the best soccer city in the country, yet one that constantly falls short of joining Major League Soccer. What a glorious past, all the ethnic clubs that sprung up when St. Louis was a top-ten American city early in the Twentieth Century. And Harry Keough was from that tradition, playing his way into the rudimentary national program after World War Two. He was shipped off to Brazil with a makeshift team in 1950. Newspapers could not believe early reports of a 1-0 Yank victory; some edited it into an English victory. But it really happened, after a virtual outsider, Joe Gaetjens out of Haiti, flicked the loose ball past the English keeper, still one of the great upsets in World Cup history. Then Harry Keough came home to live a full life as family man, coach and father of the American player and broadcaster, Ty Keough. Harry continued to play into his 30’s…and 40’s…and 50’s….His full-time job was as a postman. In between he coached junior college, and then he won five national titles at St. Louis University. What really ticked his players was that Harry was still the best player on the field. Bill McDermott, another major St. Louis soccer guy, player and broadcaster, said it used to annoy him that Harry, twice his age, could nudge varsity players off the ball, take control of it, distribute it upfield. Harry had been a pioneer as a fullback. Up to then, fullbacks had been content to blast the ball upfield, theoretically out of danger. He preferred to deliver the ball to a teammate. He dominated the game – as the coach, just filling in during practice. Disheartening, McDermott said. Harry mostly smiled at our lunch. The lovely obituary in the Post-Dispatch by my friend Tom Timmerman – definitely worth reading -- said Harry had been suffering from Alzheimer’s, but it didn’t show at lunch in May. Harry just enjoyed being out with his people. When I heard Harry had passed, I e-mailed Ty to send my condolences. “You know the saying: ‘He who dies with the most toys wins,’” Ty wrote back. “For my Dad it was: ‘He who dies with the best stories wins.’ BIG Winner, my Dad was.” The stories are out there. Now only Walter Bahr and Frank Borghi, the keeper, remain from that 1950 team. I’ll remember a powerful man with a sweet smile, who hardly needed to say a word, because we all knew what he and his mates had done. While waiting for Tet to start on Jan. 23, I think about two friends of mine from the modern Vietnamese diaspora.

They have never met, but both are making a success of their lives in this new age. Binh sells gorgeous crafts from Hoi An town, near Da Nang. Qui sells delicious pancakes and shrimp pho in St. Louis. I met Le Nguyen Binh while accompanying my wife on a child-care mission to Vietnam in 1991. We were walking through the coastal village of Hoi An, part of the Cham ethnic empire, with a cluster of residents following us. I noticed a young man in a wheelchair, smiling, listening intently, keeping pace with us. We started chatting in English, and it wasn't hard to figure out that with his language skills and intelligence and interest in computers, he was going to find his place as Vietnam became part of the modern world. We traded names and numbers, and stayed in touch. Now Binh runs an outfit called Reaching Out Vietnam, which employs people with disabilities who make jewelry and scarves and other goods. He has also founded Tien Bo (Progress), a self-help group for able-bodied people, and has also founded a computer training center. This story gets even better. Binh has since married Quyen, and they have a son named Vung, which means Sesame. A few years ago, Binh flew to a conference in Washington, D.C., and arranged a side trip to New York, staying at the very hospitable Crowne Plaza Hotel near LaGuardia Airport, where he was instantly the star resident. I could not meet him the first day, so he took off on a sight-seeing jaunt into Manhattan. Imagine the courage of a Vietnamese man, confined to a wheelchair since a medical accident in his mid teens, taking the bus to the train, negotiating the cavernous subway corridors of midtown, visiting the Empire State Building on his own. The next day I drove Binh into Manhattan, down through Harlem, alongside Central Park, to the Metropolitan Museum, which made access so easy from the garage. We found our way to the Van Goghs, where, by sheer luck, a docent was giving a lecture on, as I recall, The Flowering Orchard. I looked at Binh in his wheelchair and have never seen a more beatific smile in my life. “This is why I came here,” he said. Binh flew home to Hoi An, to resume his work. Whenever my friends are sight-seeing in Vietnam, I try to steer then to Hoi An. Last year Reaching Out was again judged one of the best small businesses in Hoi An. I just heard the other day – Binh and Quyen are expecting another child in May. * * * My other friend, Qui Tran, runs the family restaurant, Mai Lee, in a shopping center right near the Brentwood stop on the MetroLink rail line in St. Louis. When I am out in St. Louis pushing my Stan Musial biography, my buddy Tom Schwarz and I stop at Mai Lee for banh and spring rolls. Qui’s parents, Sau and Lee Tran, made their exodus from Vietnam, arriving in St. Louis in 1980. At first, Lee Tran worked in a Chinese restaurant but in 1985 she figured a way to sell her national dishes in her own place. Mai Lee now bustles at lunch and dinner, with the entire Tran family trying to keep pace with the crowds. “The new Mai Lee was worth the wait, believe us. And a weekend night crowd showed a superb mix of adults and children, grandparents and grandchildren, all ages and colors and sizes, and speaking many languages. A joyous experience,” wrote Joe Pollack and Ann Lemons Pollack in their popular dining review, St. Louis Eats and Drinks. It’s not hard to notice Qui. He’s the one with huge tattoos on huge muscles, bristling with confidence. The next generation. The American dream. I call him “my Vietnamese soul brother.” I doubt my two friends will ever meet, but they are linked in my heart. The word Vietnam evokes all kinds of images in the United States; when I hear the name these days, I think of beautiful scarves, succulent dishes, brains and muscles and courage. Happy Tet. |

Categories

All

|