Another Saturday, another meeting. Our man in Paris, Bruce-From-Canada, caught up with his old friend at the same corner. "About 10 seconds after I took this zoom photo—around 1030 or so—he gathered his things up and started walking in my direction. I moved over and got a little in front of him and offered. He only glanced. usually seems to study for a few seconds. looked at me and said, 'merci beaucoup, bonne journee' and continued on this way. Wonder if he'll miss me next week?  Earlier in this travelogue, Bruce told about his annual meeting with the man in the arrondissement -- the ritual potatoes, the thank you, in English. Bruce went back yesterday and found the man at his corner, and gave this succulent-looking helping of pommes de terre. This time, Bruce reports, the man thanked him, in French. (This sounds like a classic O. Henry New York short story, Bruce, so we are waiting for the next episode. A demain. )  Every October, Bruce goes back to the same neighborhood in Paris, and pretty much does the same things, as far as I can tell. Which is wonderful, considering that it is Paris. You know Bruce. Frequent contributor to this little website, from his regular enclave in the True North Strong and Free. Retired journalist. Former resident of Japan. And very good at pointing out the foibles of that nice benign country just below his. In our email, he counts down the days (the hours) until his next jaunt to Paris. Every year I call him a showoff, a dog, a provocateur, but knows I love showing his perambulations to my family. We made these same rounds, decades ago, once with our three children one sweet damp April. April In Paris. One more time. This year -- with all the horrors in the world -- Paris, Bruce's Paris, his corner of Paris, seems sweet and benign. So let's go with Bruce. Bruce writes: Three years ago i saw this guy standing about 50 metres from the Edgar Quinet marker near Montparnesse Market. I gave him half my potato fry and he took them without a word for the three consecutive weekends i was there. Last two years, also, I walked past the spot again today and he was there. I offered them to him today and he took them. Don't think we've said word - but today he said, "Thank you"-- in English. Ray (owner) insisted I have a cider—it was really good. Then told me he'd give me a full bottle to take back to canada when i leave. I had to turn him down since I have carry-on and liquid restrictions. (To which George adds: "Quel dommage.") (Presumably not the same meal): Creperie Montparnasse  GV: Not a day or night goes by without a photo from some angle. Fine by me. We all have memories of Paris. Marianne and I remember our pal Greg driving around Paris in his convertible on a sparkly summer night after the Tour de France, circling the Tower once, twice, three times, like a championship lap, and Tout Paris sparkled like this. I am so thrilled that the New York Times obituary editors ran a lovely obituary of Joe Christopher, a member of the early New York Mets – and my friend over the decades.

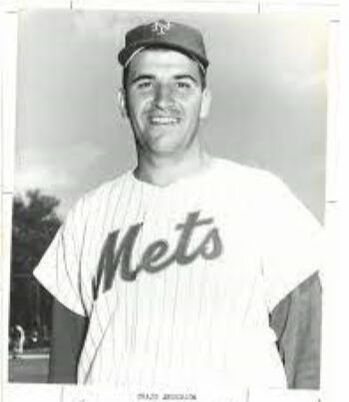

Joe touched a chord in me because he was mysterious and deep. I have learned more since he passed last week, from his daughter Kameahle Christopher. I also collected memories of Joe from two of his old teammates. In case you miss the NYT obit, here it is (for those who can access it). It is written by Richard Sandomir, now an obit writer, but previously a star sports-media critic (back when the NYT had a sports section.) https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/05/sports/baseball/joe-christopher-dead.html I became intrigued by Joe Christopher in the first year of the Mets when he was a backup outfielder. Joe was from St. Croix, apparently the first player born in the Virgin Islands to play in the major leagues. He was a mix of cultures and languages, introverted, but also comfortable chatting with some of the young Chipmunk writers covering the club. “I’m a better ballplayer than you guys think I am,” he would say, softly. Sometimes he would chat with me about mysterious religious trends. I don’t claim I understood, but I think he sensed he had a friend. He was up and he was down with the Mets but in 1964 he played regularly and batted .300. (The obit tells how in the final game he dropped a bunt single in front of old Ken Boyer of the Cardinals to pretty much clinch the distinction of being a .300 hitter. In the pressbox in St. Louis, I almost cheered out loud.) His career sputtered again in 1965 and he was soon gone from the majors. Recently, two former teammates had nice things to say about Joe: Larry Elliott, a fellow outfielder in 1965, sent this memory: “I was trying to break up a double play against Philly. I did not get down in time and Ruben Amaro hit me in the back of my head with a throw. It was my fault. I was in the hospital for five days and Joe was the only one to come and visit me." My e-pal, Bill Wakefield, sent his memory of 1964, when he was a rookie out of Stanford and reported to the Mets’ spring hotel in St. Petersburg, Fla. “The front desk says, yes, we will give you a room, and assign your roommate. So I take my suitcase to the room. Open the door, and inside is a startled Joe Christopher. I said, ‘I’m Bill Wakefield and I’m your roommate.’ He seemed surprised but said, fine” (Wakefield doesn’t need to note that Blacks and whites were not rooming together in those days. And Christopher, who had been introduced to segregation in the U.S., was surely aware of that.) Shortly, Wakefield received a call from Lou Niss, chain-smoking, worry-wart travel secretary of the Mets “Come to come to the lobby immediately. I assume it's to get instructions -- don't drink in the hotel bar -- that's Casey's spot -- don't be late for the bus -- wear shower shoes on the bus not spikes, etc. “He says – ‘ Bill we are moving you in with Larry Elliott -- make the change immediately.’ And sort of as an afterthought, he said -- I paraphrase – ‘Baseball has made progress but we are not ready for black and white roommates yet." “I have no idea -- I just want to do all the right things. So I go back down to the room -- Joe is still there -- he kind of smiles at me -- and I said Lou Niss has assigned me a different room. “I always worried that Joe thought I had complained and that was the reason for the switch. I really didn't care. "So I packed up and moved to Larry's room.Joe never mentioned it again. He and I became pretty good friends. “Joe and I laughed about it over the course of the season. He even got a big smile on his face and would say ‘Nice going, Roomie!!!’ Great guy.” I have one more memory of Joe, who could wiggle his ears with the best of them. A knot of Mets writers were taking the sun behind the Mets’ dugout during a game in Chicago in May of 1964. As the Mets frolicked to an unforgettable 19-1 final score, Joe would trot in from right field after each inning, levitating his cap with his ears – just for the writers’ sake.” Joe’s major-league career fizzled but we kept running into each other. In the late 60s, I was in Puerto Rico writing for Sport Magazine about Frank Robinson managing a team in the winter league. I was at a game in Caguas when I spotted Joe playing for Santurce…and we agreed he would ride back in my rental. Then he won the game with a grand-slam homer in the ninth inning and the fans were so annoyed that they made motions to tip my car over. We laughed about it all the way back to Santurce. I always reminded him how he almost got me killed. Joe and I ran into each other in the 1980s near Times Square. He was carrying a large rectangular portfolio used by artists to protect their work. He came up to the Times for a while, but I never saw his work -- part of the mystery of Joe. The other day, I chatted with Kameahle Christopher, a paralegal with Amtrak, who lives outside Baltimore, and asked about her dad’s inner life. “He was interested in pre-Colombian art,” she said. “He was in touch with the ancients, the Olmecs and Mayans. He was into numerology…would ask your birthday, would predict things,” Kameahle said. “He was gifted spiritually.” I asked her about her dad’s childhood and she said he was raised in Oxford, a small settlement in St. Croix. “He grew up in a small house in the mountains,” she said. “He walked everywhere, and when he came home at night, he learned to follow the North Star. He said, “‘I’m not going to grow up like this.’ Nobody had ever left the islands. He endured hardships, but he used to tell himself, ‘I’m Joe from Oxford…and if I have to walk, I’ll walk.” In his later years, Joe wanted a job teaching baseball; “he carried his baseball gear in his car,” Kameahle said. Joe would coach somebody for the joy of it, remembering how much he had learned from coaches like Rogers Hornsby, Sheriff Robinson, Paul Waner – and his driven roommate with the Pirates, Roberto Clemente. After talking with Kameahle Christopher, I felt I knew her dad better – where his inner strength came from, standing in the clubhouse, a marginal Met, telling young writers from New York: “I’m a better ball player than you guys think I am." Kameahle’s loving portrayal made me miss him even more. ## It was only yesterday that I was echoing Mark Twain (or whoever said it about the weather) when I suggested, everybody talks about Long Covid but nobody does anything about it.

Well, at least I just found another current study, this one from the CDC,. My main takeaway from this one is that nearly twice as many women as men have Long Covid. Thsi echoes a mini study done in our household, when the female has more symptoms than the male. (see CDC link directly below:) https://abcnews.go.com/Health/18-million-us-adults-long-covid-cdc/story?id=103464362 And then there's this: Long COVID patients have clear differences in immune and hormone function from patients without the condition, according to a new study led by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Yale School of Medicine. The research, published in the September 25 issue of Nature, is the first to show specific blood biomarkers that can accurately identify patients with long COVID. www.mountsinai.org/about/newsroom/2023/people-with-long-covid-have-distinct-hormonal-and-immune-differences-from-those-without-this-condition

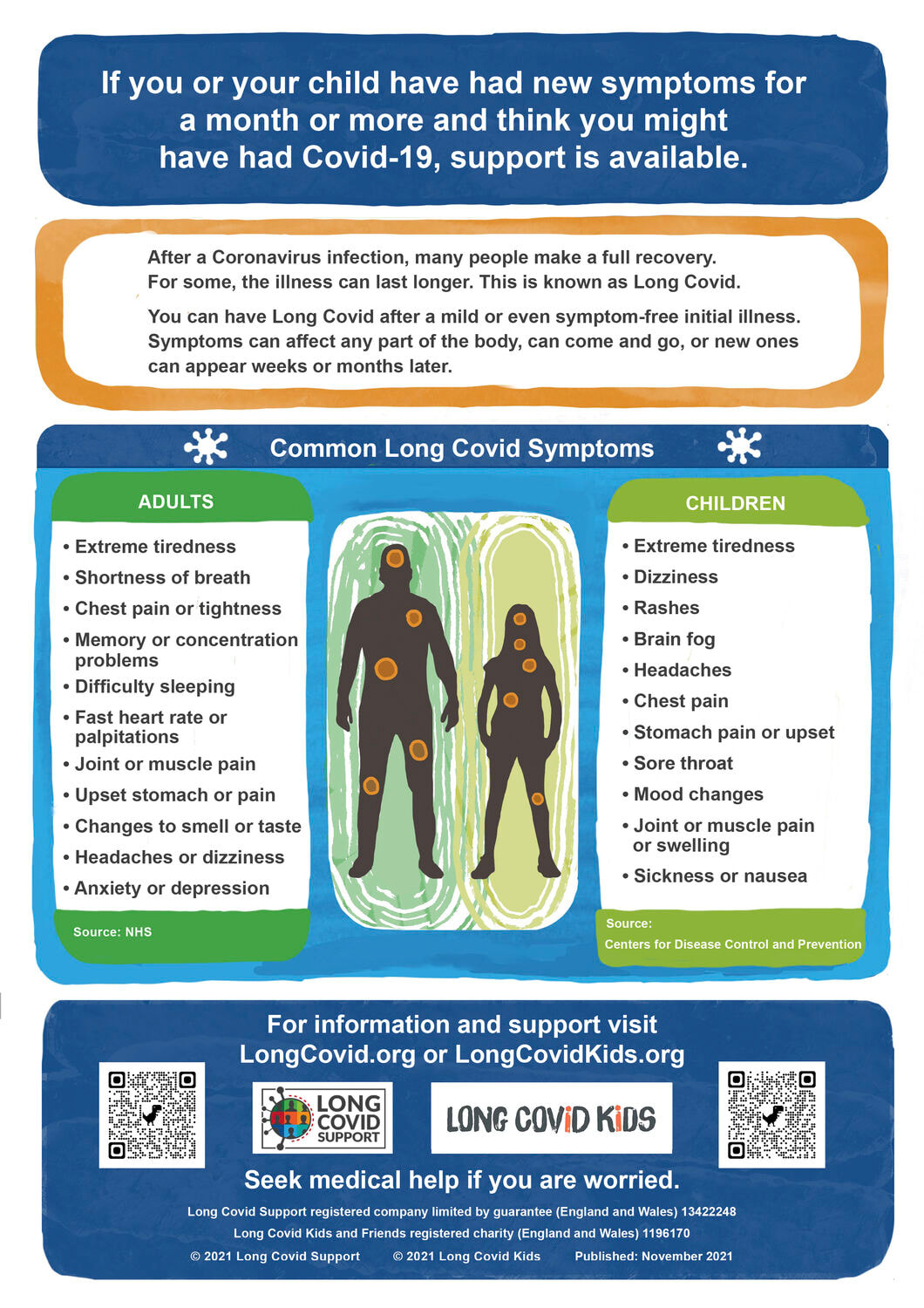

Sometimes it’s called Brain Fog. Comes and goes, like coastal fogs, but more dangerous. That ache in one limb or another that cuts down on activity and mobility, leading to expensive and grueling trips to medical centers that do not lead to any result except they found nothing. Recently, The New York Times ran, in the invaluable Health Section, an essay by Paula Span called “Long Covid Poses Special Challenges for Seniors.” It proposes that Long Covid is real and formidable and must be acknowledged before we can adapt to it. Span writes about a librarian in Michigan who was walking all over Ann Arbor, often four miles a day, until she got whacked in March of 2020, before most people had been warned by any responsible agency or government. “The virus caused extreme chills, shortness of breath, a nervous system disorder and such cognitive decline that, for months, Ms. Anderson was unable to read a book.” Still, people search for information beyond the glib explanations on the tube and the dismissals by people who think the pandemic is over, or harmless, or never existed. (I hear that even in a generally enlightened corner of the world.) On Sunday, I saw Dr. Anthony Fauci on TV on Sunday. Can’t remember what channel or what host. (Brain Fog, indeed.) But his words were current, and my general memory of the interview was that “they” or “we” still do not know much -- and Brain Fog generally may be an explanation for….whatever. On Monday morning, I poked around online to see what is available. First, since the government has apparently decided Covid is serious again, I signed up for four free test kits, via: https://www.covid.gov/tests Next, I found an article from the New York Times from only two days ago, warning that a cold virus could set the stage for Long Covid. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/cold-virus-may-set-stage-long-covid Then I found an article that says women have a 50 per cent higher chance of developing Long Covid than men https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/23/health/long-covid-risk-factors.html My general impression is that the major health institutions are just beginning to acknowledge/study Long Covid. Stay tuned, if you can still focus. However, the Web does include examples of people and regions that were taking Covid – and it’s long-form product – seriously. For example, I found a site from the UK that included a graphic about Long Covid for adults and children. (It’s from 2021 but it seems relevant -- more than ever.) It disclosed contacts for support groups in regional areas in England and Wales. Print it out. It is ideal for the refrigerator door and could also be stored in a cellphone for display when people start proposing indoor activities. Recently I met some of my longest friends – outdoors, in a park all of us know. It was wonderful – and made me realize all over again the fellowship I have missed in the past 3 ½ years. (Two of 20 came down with Covid within days and are doing okay.) Last fall (don’t tell anybody) I went to a memorial for two of my Spencer cousins, in deepest New Jersey. I absolutely had to be there, and am deeply happy that I saw other cousins, caught up on decades of life. I credit my safety to God’s grace. Some people seem to be going everywhere, doing everything. They know the stuff is all around us, but they go. Occasionally, we take a huge psychic breath and see a good friend or relative indoors, but generally, even for family reunions I recite my internal recorded announcement – that this stuff keeps morphing, and we just can’t take many more chances. Meantime, with deep sorrow, I am ducking a large gathering of good friends and colleagues in a crowded pub because I just can’t afford the flying molecules while laughing, crying and hugging. We two elders are hunkering. We’ve had two, maybe three, cases of Covid. The one at the end of 2022 was brutal, followed by a very wet and sloppy case of RSV, I think. Happy new year, indeed. When we go to our very good doctors, we talk of our trying symptoms of Long Covid. The doctors acknowledge it, and they take care of us, and we try to wait out Long Covid, whatever it is. *** Nice visual of Long Covid from the UK. 2 years old and counting. (My colleague Harvey Araton and the standout current reporter Jenny Vrentas have written about the NYT disappearing its sports section. Please open the link below.) https://mailchi.mp/nyguild.org/happening-today-farewell-to-the-sports-desk?e=5db07bd5c6 AT THE END OF WHICH I QUOTE THE BOSS

(You know which Boss) Everybody needs a happy new year.

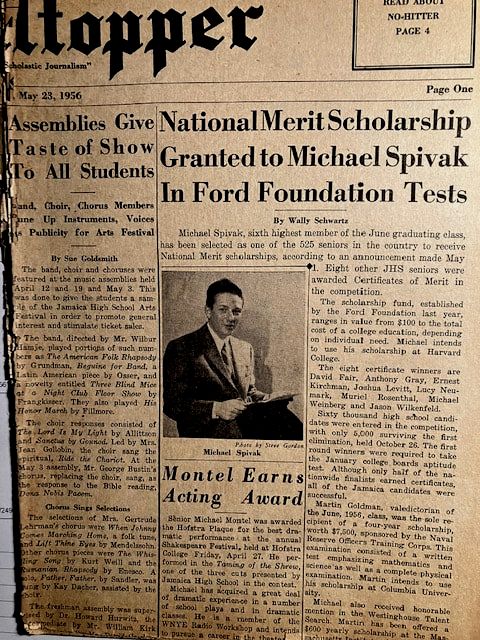

Rosh Hashanah arrives Friday, with fallish weather -- at least, that is the New York tradition. I remember one Rosh Hashanah, we had visitors, a couple we love from "out west," and we went out for dinner to a Greek restaurant, a couple of towns over from us. The weather was so early fallish that the restaurant had opened some windows up front, to let the crisp air enter. A group of celebrants from a nearby temple was passing the restaurant. They were in a bouyant mood, and spotted the four of us at the window. One celebrant asked the question you often hear on city streets from the faithful seeking to expand the flock: "You Jewish?" (Pronounced "Joosh?") Three of us pointed at the fourth, a Jamaica High grad a few years younger than me. The Judge. That made the roving band happy and they began serenading us through the open window, shofar blaring. That made the four of us happy. We were home. In New York. * * * There's a lot of bad stuff these days. War. Floods. Earthquakes. And to employ the generalization, "politics." But I'm taking the blue sky and bright sun as a Rosh Hashanah sign that things are okay, at least as I type this. I'm sending out greetings to friends and to family, including my Australian second cousin Jen and her New York husband Sam, undoubtedly celebrating in their way in their lovely little village in Southwest France. And to my New York-born friends, some of whom pop up in Comments on this page, who have made Aliyah, that is, moved to Israel -- Mordechai, Hillel and Mendel, and his NYC dad Ahron, seen dancing with quick feet at family celebrations. L'Shana Tovah. *** And then there is this. Back in the day, Jean W and Jean R were friends at PS 131, not far from Jamaica High. They did stuff together, right through high school, went to separate colleges, and then Jean R made aliyah, to a kibbutz. After a time, Jean W visited Jean R in her kibbutz, and then showed us photos in a luncheonette along Union Turnpike. The other day, a bunch of us from the Class of 1956. living not far from Cunningham Park in Queens, gathered for an informal BYO picnic, under trees that must have been growing when my mother and my Irish Nana were swinging me in the nearby kiddie park, still standing. Familiar park. Familiar faces. As 20 or so gathered, we talked of others ("Good friends we had/ Good friends we lost/ Along the way" -- Bob Marley, "No Woman No Cry.") And in the center of the group was Jean W, sitting alongside Jean R, back in New York for a family visit. It made me immensely happy to see these two friends, as if it were 1950. *** L'Shana Tovah. Happy New Year. It's universal, at least where I'm from. Brendan LoParrino and his teammates had an interesting summer vacation. Their soccer club in Putnam Valley, N.Y., visited Italy, trained at the facilities of the fabled AC Milan squad, and attended a Serie A match at San Siro. Christian Pulisic, the scoring star of the U.S. national team, moved from Chelsea to AC Milan during the off-season, and he was in the lineup for the match with Torino. Not only that, but Pulisic scored one of his typical goals – sharking the side of an attack, waiting for the ball to come loose, and when it did, Pulisic kicked it into the far left corner. Only Pulisic knows if he had spotted a noisy American contingent in the second deck, but that side was the closest to his goal, and he slid on the grass to celebrate as the crowd cheered, syllable by syllable: “Pu-li-sic! Pu-li-sic!” That goal was not guaranteed in the prospectus for the training week -- and players and adults from New York appreciated it. For American elders still boggled by the popularity of soccer in the mainstream of culture, this summer camp – a luxury, to be sure – demonstrates the hold of the world’s most popular sport on the younger generations, well into middle age by now. Brendan LoParrino even carries a nickname, based on Jordan Henderson, the smooth and unselfish former captain of Liverpool, and also leader of the English national team (now playing for big bucks in Saudi Arabia). Brendan’s teammates call him “Hendo,” Henderson’s nickname, and during a training match, the opponents heard the nickname being shouted, and asked what that was all about, so the Putnam Valley players filled them in. Soccer is a language all its own -- and spreading around the U.S. Brendan, age 13, going into eighth grade, recalls the trip: “Our team started training before traveling to Italy. We had normal training during the week at our club. We also had two practices in Italy, one with our coach, Angelo, and another with a professional trainer. “I was not sure what it was going to be like in Italy. I was excited and felt that the players there were going to be really good." He added, “I do not think soccer was that different and thought it was better in Italy. They have nice training facilities and I liked the locker rooms. The watermelon was really good at the concession stand. The coaches were more relaxed and let their players play. “I learned about playing with kids from different coaching styles. It was also different playing in such hot temperatures.” "Our first game was against Pescia. It was 102 degrees and we won. I scored two goals and one was on a free kick. We then visited Coverciano/museum and trained in the morning. We tied the next game against Fornacette in Tuscany. "We controlled the ball but could not score. The next day we went to a professional game at San Siro stadium. AC Milan played Torino. AC won, 4-1, and both Giroud and Pulisic scored. This was the best professional game I have been to. We lost in our last game against (Pro Sesto) and they were very good. They are the youth academy for the Serie C team in San Giovanni, Lombardy.” The trip was not all soccer. The group made a side trip to Lake Como and took the ferry, visited Montecatini Terme and Florence.

“We climbed the Leaning Tower of Pisa with my sister Kaitlyn. I was happy to get soccer jerseys for AC Milan, Italy and Juventus." Clearly, the vast majority of American youth players do not have the luxury of an overseas trip, but spend the summer working on their skills much closer to home. Youngsters who do get to make a trip like this can bring home the feeling of how much soccer means to the fans – the tifosi – whose loyalties are often inherited at birth. That comes across on television in the U.S. – and also in the fast-growing Major League Soccer with its middle-sized stadiums and rituals and traditions. Soccer is here to stay, and young players like Brendan LoParrino are fortunate enough to bring some of that ambiance back home with them. Brendan said: "I look forward to this upcoming season with my core team at Palumbo soccer club. We joined a new league and will be playing teams further north that are competitive. We have a tournament in Orlando this December and one next season in Portugal. I will be playing JV tennis this year and look forward to playing varsity soccer at my school. I am alsolooking forward to the World Cup in 2026." The U.S. and Canada and Mexico will host a North American World Cup, "only" 32 years after the U.S. was host to a World Cup that filled stadiums from coast to coast and made millions of new fans. The U.S. has not come close to winning a World Cup -- but the younger generations have their hopes, respectful of the history of soccer, over there. *** Thanks to Brendan for sharing his impressions via his dad, Joe LoParrino. I know Joe through a mutual friend, the garrulous and knowledgeable Alan Taxerman, an athlete and lawyer who worked with Joe LoParrino. Big Al often shared his strong pro-Yankee and pro-Mantle opinions with the world. through this site. When Big Al passed in 2018, Joe LoParrino invited me to a memorial I could not attend. We have never met, but we are bonded through our mutual friend, and now soccer. Thanks to Big Al, and Joe, and Brendan. (Randy was on a writing burst so I am including this. GV.)

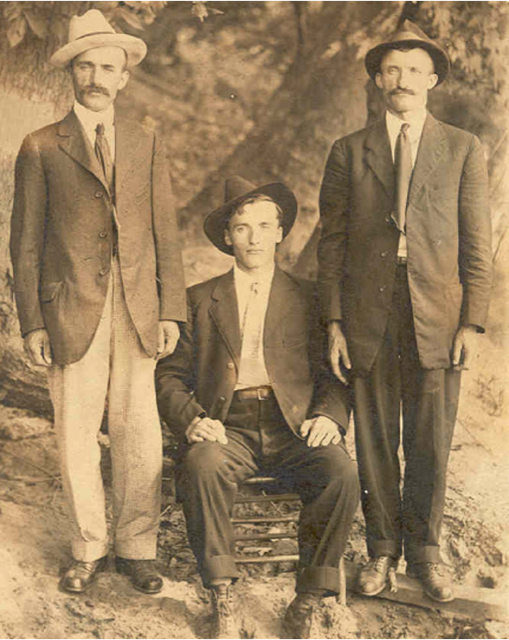

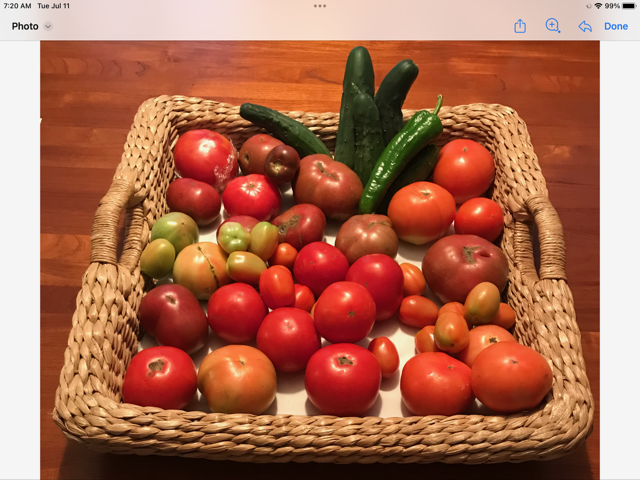

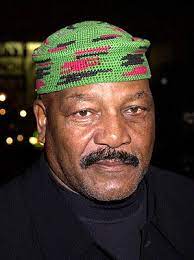

By Randolph Fiery Geneva’s father, Robert Martin Zando, on the left in the photo of the three brothers, was an Italian stonemason and builder from Falcade, Italy. I think he first came through Ellis Island in 1910. He had built a large stone home in the Dolomites, not very far from the Austrian border. He was saving money to bring my grandmother, Caterina, and my uncles and aunt, Sixtus, Abraham and Mary to America, when World War I broke out. The Germans turned their large stone house into an officer’s home and office. My grandmother and the children lived in the attic and cooked, cleaned and were in essence servants to the German officers. My uncle Sixtus was a teenager, and they put him in a work camp. Because of the war, my grandfather was unable to bring grandmother and the kids to America until 1920. They settled in West Virginia because there was a need for stone workers to build structures for the mining industry. My grandfather was one of the first men building the beautiful stone bridges on the Skyline Drive and Blue Ridge Parkway. He also built a building – now in the national historic register -- made of coal in Williamson, West Virginia. My mother was the first of the family born in America and in 1940 or 1941 she was able to enter West Virginia University and receive a degree in biology. But I have an even better story, her older brother, Sixtus was a teenager when my grandmother and the three kids arrived at Ellis Island. Sixtus had a damaged leg and the officials at Ellis island labeled him a “cripple.” They were going to let my grandmother and two of the children enter America, but they did not want to let that “cripple boy” come in. My mom told me, that her mother and her siblings waited for days, if not weeks trying to get Sixtus allowed to enter America. She said her brother was prepared to go back to Italy and live with the family, but they somehow got the officials to finally let him in. They moved to the coalfields of southern West Virginia because there was lots of stonework to support the coal industry. Sixtus was a teenager with a damaged leg and they placed him in a first grade classroom to learn English. That young “crippled boy” did OK. He ended up graduating from medical school at Loyola University in Chicago. He had the money to pay for my mom going to college. Another side story: during my mom‘s senior year in high school, she won an academic scholarship to a small college in West Virginia. When they found out she was Catholic, they took away the scholarship. She worked for a year, and then her brother paid for her to go to school. She was the best human I have ever known.  Randolph Fiery often sends me photos of his garden's produce -- the showoff. Randolph Fiery often sends me photos of his garden's produce -- the showoff. (Randolph Fiery is a regular on this website, with his spiritual passages and frequent odes to the vegetables he grows in southern Virginia. On Tuesday he sent the following :) Can you deny, there's nothing greater Nothing more than the traveling hands of time? Sainte Genevieve can hold back the water But saints don't bother with a tear-stained eye -- Son Volt (rock band) Friends, The sun has not risen in the eastern sky. Yet I am awake and thinking about those “traveling hands of time……." The three men in the photo are brothers: a photograph taken more than 100 years ago. Three brothers, who came through Ellis Island separately between 1910 and 1917. But on this day, they stood together in New York City to have their photograph taken. A recognition of their struggle to come to a new land. It would take another 10 years for them to earn the money, to weather the storm of World War I and bring their wives and children to this new land they called America. It is a family story. A fading story held by a few and controlled by the “traveling hands of time.” They were men who could grow gardens. Tomatoes, basil, potatoes were their friends. And yes, grapes… they knew how to make wine. They knew how to cut stone, build houses, and one of them, my grandfather constructed bridges and even a building of coal. Family stories fading with age. But on this day, the summer heat is moving toward the garden. It has been a good year for the garden. Tomatoes, Swiss chard, peas, eggplant, peppers and cucumbers. . So on this day, I want to thank you for your hard work, your struggles, and for more than you can imagine, everything that you have given to me. It seems that we never really know what impact another human can have on the life we lead. But on this morning, I am glad that you are still breathing. --Randolph Fiery *** Several friends wrote in to ask, who is Genevieve? I thought I knew. When I was writing the biography of Stan Musial, a gent from southern Virginia, Randolph Fiery, contacted me to tell how Musial intersected his family’s life. In 1939, Musial was a kid pitcher in Williamson, West Virginia. The Musial bio says: “On Sunday mornings Musial would attend Mass, and Geneva Zando, a senior in high school, would observe how devout and handsome he was on the Communion line. Soon she would marry Howard Fiery, who lived in the house Musial had entered by mistake.” The book explains how late one Saturday night, the boy from Donora, Pa., wandered into an identical home on a main street of the coal town. Things could have gone wrong, but the Fiery family, knowing he was a Cardinal farmhand, directed him to the nearby house where he was staying. As Musial became Stan the Man, one of the greatest players of his generation, or any generation, Randy often heard the story about that long-ago Saturday night. Randy says it used to frost his dad when talk turned to the nice young man who attended Mass that summer in Williamson. Then Randy launched into gear about his mom: "Sitting here now I realize that I really didn’t tell you much about my mother. Yes, she was a saint. "I believe that she was unusual for her day and place and time. "My grandparents were Italian, but mom was Born in BLOODY MINGO COUNTY, West Virginia, during the deadly coal wars between the mine owners, and the young United Mine Workers union. "She was a person of science, earned a biology degree in 1942 and moved to Waukegan, Illinois, and worked in the laboratory of a Catholic hospital. She ended up marrying my dad, a college football star at William and Mary. "She raised five children, four boys, and a girl on three acres of land in southern West Virginia. My dad worked construction, building bridges. His jobs were in Virginia and he only came home on Saturdays and Sundays. She cooked, cleaned, challenged her children to foot races in the yard. She never cursed, never talked badly about anyone, never whipped us, and at 85 years old her arms were still like rocks. She took us to church every Sunday, but she never spoke of religion. "She was humble, self-sacrificing and always forgiving. Kindness and compassion flowed through her veins. She was funny and a good storyteller. But mostly she did not show herself and let other people draw the attention. "As I said, she was a good storyteller. Some stories I had a hard time believing, but it ended up that they were true. She was a cousin of Pope John Paul l, Albino Luciani. "The pope’s father was a stonemason in Falcade as was my grandfather and his brothers. "I’m just babbling George. I can’t really describe a saint, but every human that knew her loved her." I didn’t like Atlanta when the Braves moved there in 1966. Far as I knew, it was merely the Deep South putting on a somewhat civilized face for tourists. This was only a year after Lester Maddox, who wielded a mean pickax-handle, closed down his infamous Pickrick Restaurant, preparatory to his successful run for governor. Charming. Plus, I resented the city stealing the Braves from Milwaukee. Get your own team. However, I began to appreciate Atlanta more in the 70s when I was a news reporter, sometimes popping into the Times bureau, getting a broader picture of the area. After Atlanta somehow acquired the 1996 Summer Games, I visited the city often, still wary. One day in 1994 or 1995, in an Indian restaurant downtown, I was having lunch with a colleague who had grown up with the King kids in Atlanta. She was assuring me her hometown would come off well in 1996. During the meal, she nodded discretely at a distinguished Black woman at a nearby table. “That’s Shirley Franklin,” my friend said. “She’s going to be the mayor of Atlanta one of these years.” I knew Atlanta hadn’t had a white mayor since the 1970s. During the 1996 Games, the major would be Bill Campbell, who lived next door to an apartment complex in Inman Park, where the Times delegation was quartered. We appreciated seeing his security car parked out in front. I also got used to Mayor Campbell’s brash style, including his remark during an informal press conference when he nominated our raffish lot of reporters to serve as targets during the Olympic rifle competition. Okay. As it happened, Atlanta did a fine job in the Games – despite the bomb in Centennial Park one Saturday night that killed a bystander, set off by a white terrorist who would have been right at home in the murderous mob of Jan. 6, 2021. (He is “away” now.) The highlights of the Games included brave, stricken Muhammad Ali struggling up the stairs bearing the Olympic torch while the world held its breath, and a closing ceremony concert by Stevie Wonder singing John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Atlanta got a lot of things right in 1996 and has kept on from there. As my friend predicted, Shirley Franklin became the first black female mayor, serving two terms from 2002 to 2010. and recently Keisha Lance Bottoms served as mayor from 2018 to 2022 and is now working in the Biden administration. But wait. There’s more. Soft-spoken lawyer Stacey Abrams twice ran for governor and has become a national influence on thought and deed. Voters have elected two Democrats to the Senate. And in 2020, Fani T. Willis was elected district attorney of Fulton County, and almost immediately inherited the screaming, stinking mess known as Donald J. Trump and his co-conspirators. In an excellent profile in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Tamar Hallerman tells how Willis is the daughter of a criminal defense lawyer attached to the Black Panthers of the 1960’s. Later, he took his daughter (FAW-nee, Swahali for “prosperous”) to work with him – doing his filing, as a tyke, and watching what he did, and what he cared about. She later went to Howard University and then Emory law school. Almost from the day she was sworn in, Fani T. Willis has been collecting string on the Trump plot to sabotage the Georgia balloting of 2020. Recently a grand jury indicted the former President (can’t you just hear that petulant whine: “All I want….”) and 18 others in a RICO case. Willis set a stern tone for the coming trial, putting out a memo to her staff to not respond to the inaccurate racist blather that comes from Trump and his acolytes. To quote Morehouse grad Spike Lee, she told her people: Do the right thing. Fani Willis does not lack for friends and colleagues and admirers who can explain her, the way former mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms did the other day on tv. And watchers of MSNBC are familiar with another Willis contemporary, Gwendolyn Keyes Fleming, the former district attorney of neighboring DeKalb County, from Rutgers and Emory law school, who more recently worked in the federal government. Clearly, this is not the Atlanta I first visited in 1966. My two sisters and their families are scattered around the northern suburbs. Our son David got a great break by working at the Journal-Constitution, which prepared him for a tryout at The New York Times, where he now works. If his family had settled down there, I could have seen us living in the piney northern suburbs – at least from fall to spring. I got to like it there. Atlanta is not the Georgia of Lester Maddox. Instead, it has been threatened by a latter-day terrorist from my childhood corner of Queens, New York, who wields not a pickax handle but the rhetoric of a thief and a racist and an anarchist. Up north in New York, I give thanks for staunch line of Black female public figures – a lineup as potent as the all-stars on the Atlanta Braves -- leading up to Fani T. Willis, who has been preparing for this moment nearly all her life.

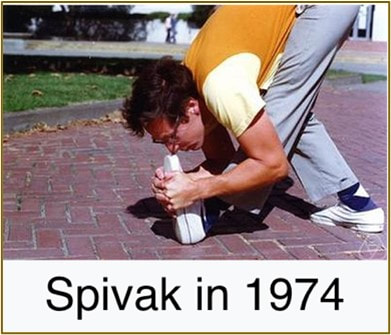

In the terrible year of 1968, with war raging in Vietnam, with MLK and RFK being assassinated, a sound emerged from a funky pink house in the Catskill mountains that some of us had been awaiting, whether we knew it or not. “It’s like you’d never heard them before and like they’d always been there,” Bruce Springsteen would say, several decades later. This is true. I can attest to the feeling of desperation in the late ‘60s, and how it was tempered by the music from five troubadours – one from Arkansas and four from Canada. (Toronto was a melting pot for music that would be heard around the world.) The five musicians brought their separate gifts, in a visual mishmash of floppy country thrift-shop clothes, indistinguishable in their very white slouches. But gradually we sorted out Richard Manuel from Rick Danko from Levon Helm – the token southerner -- from Garth Hudson – now the last survivor, with his weird beard and instrumental sounds – and from Robbie Robertson, who died Aug. 9 at the age of 80. Robertson’s life is captured in the excellent NY Times obituary by Jim Farber: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/09/arts/music/robbie-robertson-dead.html Robertson came off as the dominant Band member in the documentary, “The Last Waltz,” by Martin Scorsese, which was made as the Band broke up, with a glorious final concert cast, in San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom on Nov. 25, 1976. Scorsese was obviously taken by Robbie Robertson’s charisma and intelligence and ambition, which helps explain why the boys were breaking up the band. When the movie was released in 1978, Marianne and I took our youngest, David, to see it in The Village (Dave clarifies all in his comment, below) -- the start of a family tradition. Every year at Thanksgiving, David pops in a DVD of “The Last Waltz,” as we give thanks for life and also the music and point of view of the Band, including Jaime Royal "Robbie" Robertson. I had a few glimpses of The Band. In 1974, as a news reporter, I was assigned to cover the Long Island and Manhattan stops of a national tour by Bob Dylan, and the five musicians who had melded as members of Dylan’s band. The only Band member I actually met was Levon Helm, when he was cast by Michael Apted to portray Loretta Lynn’s father in the movie, “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Another time, I saw Danko and a haggard Manuel perform at a Pete Fornatale fund-raiser for a food charity, in the Village, not long before Manuel committed suicide. In 1980, there was a “grand opening” for the movie “Coal Miner’s Daughter” in Nashville. Maybe a bit sloshed, Levon played backup to Loretta and Sissy Spacek as they sang some of Loretta’s greatest hits. He was so modest, did not need attention. I never did meet or eyeball Robbie Robertson, but his mystique grew in his post-Band years. People came to know that his mother, Rosemary Dolly Chrysler, was a Mohawk, raised on the Six Nations Reserve near Toronto. His actual father (who died young in a car accident) was not named Robertson but rather was a gambler who was Jewish. “You could say I’m an expert when it comes to persecution,” Robbie Robertson wrote in his memoir, “Testimony,” issued in 2016. One of my favorite Robbie Robertson songs is “Stage Fright,” about a singer – maybe Bob Dylan himself, who comes off very nicely in Robertson’s book, offering a functional car to the young guitarist coming to play backup in Dylan’s band. https://www.google.com/search?q=lyrics+stage+fright+the+band&rlz=1C1GTPM_enUS1061US1062&oq=lyrics+stage+fright&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqBwgAEAAYgAQyBwgAEAAYgAQyBggBEEUYOTIICAIQABgWGB4yCggDEAAYhgMYigUyBggEEEUYPNIBDzEzMDU5MzU3NTRqMGoxNagCALACAA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 Others think the song is about young Robbie Robertson himself. Still coalescing as a band, the five musicians made a pilgrimage to a soul-music center in Arkansas, and invited Sonny Boy Williamson for some soul-food in a Black neighborhood. Home-boy Levon tried speaking polite Arkansan to a couple of white cops, only to have the five run out of town. Another of my favorite Robbie songs is “Acadian Driftwood,” about French settlers on the Canadian coast, some of whom later migrated southward to join relatives in Louisiana, only to realize they were still outsiders: “Set my compass north, I’ve got winter in my blood.” As the settler prepares to go “home” to Canada, the language shifts into French: “Sais tu, Acadie j'ai le mal du pays” (Do you know, Acadia, I'm homesick.) In later decades, Robertson performed and wrote music that reflected his Mohawk genes: https://www.samaritanmag.com/musicians/qa-robbie-robertson-why-he-kept-quiet-years-about-his-heritage In his later years, Robertson gravitated to Los Angeles, but he continued to write and perform songs that spoke for outsiders, including himself -- part shtetl, part rez. ### There is nothing more dispiriting to a baseball fan than to see a favorite team toss

helpful players overboard with two months left in the season. Wait, what about those tickets I bought for three weeks from now? Does that mean we don’t have a chance this year? Of course, baseball fans are smart enough to smell the reek of failure – particularly the demanding patrons of the Mets and Yankees, who can figure stuff out for themselves. The Yankees are trudging along last in a very tough five-team division – enough to make The Boss up there in the sky (you know which Boss I mean) toss a thunderbolt of rage at the people running the Yankees. (Actually, the Boss is responsible for the current owner and the current general manager of his team.) The Yankees have been followed by rumors of jettisoning unproductive players with two months to go in this season. A player dump? So very un-Yankee. But the other New York team is making the Yankees look downright successful and stable. I am talking here about the Mets, who, as I am typing this Sunday evening, have jettisoned their best active reliever (David Robertson) and one of their best starting pitchers, Max Scherzer, after he staged a tantrum because the Mets had dumped Robertson. Let’s face it. The Mets would not be in this mess if Edwin Diaz, the best relief pitcher in the majors last year, had not torn up his knee in a celebration dogpile in the World Baseball Classic. Everything bad the Mets have done – let us count the ways – stems from that horrible moment of destructive joy. Robertson is a useful late-inning pitcher – good enough to give Mets fans hope in the late innings this year. When Robertson was dumped, Scherzer forced his trade for a prospect. That really stinks – for Mets fans. But the Mets – and the Yankees – and most teams have played that game over the years. I have to inform New Yorkers: this is not all about them. The nicest thing about this season is the high standing of the Baltimore Orioles and Cincinnati Reds in their respective years. I have soft spots for both – the towns, the teams, their distinctive colors and uniforms – and would love to see them in the World Series. Meantime, the two New York teams are struggling. Too bad for fans who committed their hearts and their dollars. Mets fans can wail about the departure of Robertson and the egomaniacal master, Scherzer, pacing the dugout between innings, or babbling on his days off. But historically, the Mets have benefited from other teams dumping somebody. (Donn Clendenon, upgrading the 1969 Mets the day he arrived.) Remember 2015? Of course you do. The Mets brought in Yoenis Cespedes, who tore up the league for two months and helped the Mets reach the World Series. Good move by the front office. Of course, some other team (Detroit) had dumped Cespedes to the Mets his fourth team in two seasons. Fans hate it when it happens to them. One of the most demoralizing dumps I have seen was in 1992, when the Mets were clearly not going to win anything. So the brass dumped David Cone, a charismatic competitor with a 13-7 record for a mediocre team, who then helped Toronto reach the World Series and, three years later, helped the Yankees reach the league finals. Mets’ fans groused, insisting that Cone should have remained a Met. Of course, the Mets had picked him up for a reserve catcher after the 1986 World Series. “Wait til you see this kid,” wise old shortstop Rafael Santana told me on opening day. Other teams have traditionally picked up highly useful players, I remember when my Brooklyn Dodgers acquired Sal (The Barber) Maglie in 1956, and the main concern was whether Maglie and the Dodgers’ centurion right fielder, Carl Furillo, could co-exist in the same clubhouse, given their long Manhattan-Brooklyn feud. The Barber and the Skoonj bonded over some Scotch in a hotel room, and made Dodger general manager Buzzie Bavasi look like the genius he was sure he was, and Maglie helped the Dodgers reach the 1956 World Series. That other New York team, the one in pinstripes, has a history of acquiring useful parts from bottom-feeders, most notably their Kansas City cousins. In 1964, the Yanks were negotiating for a long-time antagonist, Pedro Ramos, a pitcher who was often challenging Mickey Mantle to a footrace. The Yankees could not manage to get Pistol Pete until after the Sept. 1 deadline, but he helped them into the World Series, when he was ineligible to pitch. (He never did get to race Mantle.) Fans are still waiting to see what kind of deals can be done in the final hours before this year’s 6 PM deadline on Tuesday. However, the Mets’ blight hangs over Queens like the gritty odor of a Canadian forest fire. Maybe Edwin Diaz will be back, intact, next season. To some of us sad-sack Mets fans, that seems like a long time. A very long time. I have received so many emails and calls since the announcement that the New York Times’ sports section will be closed.

It seems like the best thing to do is try to answer many of them at once – and ask for your own reactions and your memories. From my standpoint, this has been coming on for a long time, since people stopped reading newspapers – a terrible trend for swaths of the country that no longer have the information to cope with government and business and health issues. When I see once-great papers like the Louisville Courier-Journal get Gannetized, my heart breaks. The sports sections were particularly vulnerable. While I was still working, valued colleagues, particularly sports columnists, began to be disappeared, sometimes en masse. Fortunately, The New York Times made a lot of good decisions – a web presence, color in the paper, and more valuable news and information about health and safety and cooking. Perhaps the best business decision was to use the sparkling printing plant in College Point, Queens, to print other newspapers. The Times now prints 60 papers, from dailies to weeklies, news and ethnic. That pays some bills around the paper. Since I retired at the end of 2011, the Times has flourished around the country and around the world, using other print plants. However, deadlines had to conform, with available press time, which ultimately meant the Times had to stop covering games -- Mets games, Yankee games, Giants games, Jets games, etc. To its credit, this great paper continued to report and comment about the major issues in sports – brain concussions, how money was made and spent, gender issues, racial issues. Inevitably, the excitement over the “local” teams was lost. I felt the absence of emotion. Readers felt it. Speaking for myself, in retirement I had more time to read the paper – the print version, in a blue bag, in my driveway every morning. My friends in the Times printing plant call it “the daily miracle,” and for me, it is. In recent days, I have been happy to see stars like Linda Greenhouse writing about John Roberts’ Supreme Court, and Michael Kimmelman writing about New York’s perennial albatross, Penn Station and Madison Square Garden. I love to find the great reports from Dan Barry and I love the wit of Vanessa Friedman, writing about style. The Health section every Tuesday sparked my interest in evolution. But now the sports department is going to be disappeared, while promising new jobs for great editors, great reporters. I hope they appreciate Kurt Streeter, whose most recent Sports of the Times column savaged the pro-gambling baseball commissioner and the owner of the A’s, as they prepare for the A’s to vacate Oakland for Las Vegas. Readers feel there is a hole in their lives. I can tell you about my sense of loss of the Sports Department – once a bustling clubhouse of colleagues, specialists, who schmoozed and kibitzed across their specific skills. They formed a team. The Times claims it will find suitable work in the many departments left. My reporter friends are great journalists, who can do anything -- Joe Drape, Jere Longman, John Branch, Ken Belson, Andrew Keh, and so on. In 2004, at the Summer Olympics in Athens, a demonstration broke out, and Juliet Macur went right toward it, getting tear-gassed but coming back with information. Juliet will be covering the Women’s World Cup of soccer in Australia and New Zealand later this month. She can do anything. So can they all. But something will be lost – particularly the presence in a sports setting of specialists like Tyler Kepner, the baseball columnist, who has been writing since he put out his own newspaper as a young kid in a Philadelphia suburb. I hope they can find a regular spot for his voice as he explains the goofy doings in his chosen sport. Meanwhile, the Times has spent a ton of money on a website, The Athletic, which apparently has people everywhere. I have glanced at The Athletic, and I gather it has a few colleagues of mine who used to work in newspapers. But I want to add that a lot of websites have box scores and opinions and transactions. I will continue to seek out columns by my friend Sally Jenkins in the Washington Post, whom I call “The Last Sports Columnist.” (Did you see her recent masterpiece on Martina and Chris?) For my daily fix of soccer and snark, I will continue to read columnist Barney Ronay and savvy reporters in The Guardian. Local NY sports? Newsday and the Post (even though I try not to ever pay anything to the Murdoch clan.) I am sure the byline stars from Sports will prosper in other parts of the paper. They are familiar with the style marshals, the wise old elephants in the office, who make sure the paper looks and reads professional. I always liked to watch the faces of colleagues in the pressbox as we dickered with the home office over a comma or a semi-colon. I appreciate the nostalgia for the Times sports section. Please feel free to share your opinions, your best memories. One of the many great things from The New York Times recently has been a canvass of 17 – count ‘em, 17 - opinion columnists of a cultural icon that best exemplifies the United States. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/06/20/opinion/nyt-columnists-culture.html After perusing the list, my first reaction was how many Times opinion writers chose highly accessible television series – many of which I have never seen. Please, this is not a value judgment. We all need entertainment/stimulation that is more enjoyment and less work. I’m likely to be watching the Mets – my patience with these poor slumping mugs is not endless – and coming soon, the Women’s World Cup of soccer, a quadrennial delight. And I spend way too much time gaping at the Bureau of Wishful Thinking, hoping for a few guilty verdicts, and soon. The NYT’s feature demonstrates that many of its best and the brightest commentators have a life, which helps them understand this vast and divided country as well as relax and enjoy. I was tantalized by all 17 choices, but a few that stuck with me that most: ---Bret Stephens got me by picking the film “Pulp Fiction.” Sometimes, just for fun, I go fishing on Youtube for the last 20 minutes or so, starting with Harvey Keitel as Winston Wolf a mob fixit man wearing a tux who cleans up a very messy murder scene. The movie ends with John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson as two gunslingers who foil a hapless couple trying to stick up a diner. I don’t know if that segment is about America or rather about LA a very distant generation ago but either way I love it. ---David Brooks wrote: “I nominate Blind Willie Johnson’s 1927 rendition of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” Brooks added: “Johnson is playing his slide guitar in a way you’ve never quite heard a guitar played, and he is not really singing so much as humming, groaning and intoning. There are few words, just verbal renderings of woe.” ---Nick Kristof wrote: Horatio Alger’s “first blockbuster novel, published in 1867 as a serial, was ‘Ragged Dick.’ Its hero is a 14-year-old shoeshine boy who sleeps on the streets of New York City. While Dick is illiterate and likes to gamble, he has a good heart, a willingness to work hard and a strong sense of honesty.” This being my personal therapy website, I came up with my own quirky visions of America: --- “The Sopranos” – the only series I have watched in the last 40 years. Not just for Tony and Carmela but also the Italian hitman Fiorio (“Mr. Williams") muscling the smug golfing doctor into the water hole or the cool one-legged Russian woman who dumps Tony. I still ponder what the final episode meant. --- For novels about America, I could choose Mark Twain, but I will stick with Thomas Wolfe, who taught me how to read and feel as a teen-ager. Most of his books are based in Asheville, N.C., but I would nominate “O Lost,” a revision of “Look Homeward Angel,” with the first section (inexcusably excised by the original editor) about of a teen-ager standing on the highway south of Harrisburg, sassing Confederate soldiers as they march toward Gettysburg, summer of 1863. That boy will become Thomas Wolfe’s father in North Carolina. The fissure in the United States that summery day is as real as today’s news. ---Every Thanksgiving, our son David plays the classic Scorsese film, “The Last Waltz,” the final concert of The Band – four Canadians and Levon Helm from Arkansas, with guests as diverse as Muddy Waters, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Emmylou Harris, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, the Staples Singers, Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan, singing “Forever Young.” However, if I have to choose one icon that catches America, I will go classical. I think of the long flights I used to take, over the Great Lakes or the Rockies in daylight, or the reverse flights, heading home in the midnight hours, the twinkling necklaces of highway, lone cars, small towns, rivers, so much space, so much promise, so much beauty, from 30,000 feet. Then I think of the composer from Bohemia, somehow getting himself to deepest Spillville, Iowa, feeling the vast space, hearing America’s great asset, the spirituals and the soulfulness of the Blacks, and how Antonin Dvorak put it together in “Symphony No. 9 --From the New World." (And if I have a choice, conducted by, himself an icon, Leonard Bernstein): Your choices/suggestions/comments?

They pitched for the Mets in different centuries – Jacob deGrom at the start of his career, Roger Craig near the end of his.

They both won over the fans – deGrom for his long-haired exuberance in his early years: Craig for his gnarly perseverance near the end. DeGrom was shut down this week, at 35, facing perhaps two years after Tommy John surgery; Craig died at 93. *** In deGrom’s final years with the Mets, I always felt I was watching his last game. The Mets never hit for him; that flaw was not of his making. He had so many injuries, yet he gritted himself through five, six, seven innings before trudging off the mound, leaving behind a streak of strikeouts but not so many victories (82-57 record in nine truncated seasons with the Mets.) In a time of gigantic bullpen staffs and strangely influential analytic types, deGrom seemed temporary, vulnerable, doomed in a professional sense, despite the pitches that curved and slid and sizzled. It was pure baseball joy to watch him – fielding like the shortstop he once had been in college, swinging the bat like the daily hitter he could have been (and who is to say, maybe still could be?) He was a complete ball player, except for the flaws. Then he was gone, like a main figure in one of baseball’s strange layer of supernaturalism in “The Natural” or “Damn Yankees,” or “Field of Dreams.” Flash. Bang. Gone. Why did Jake go? Without getting into the dollars, it seems to me that the Cohen Mets made a respectful, calculated offer, based on the belief that deGrom’s apparatus would fall apart one day soon. The Mets front office seemed to be waiting for a sucker franchise whose officials did not read the papers or listen to talk radio or consult the available analytics. I have a parallel theory: As the Mets fell apart at home in the post-season last year, fans booed Chris Bassitt as he trudged off the field. “Shame!” I yelled at the TV. Fans in grand old franchises like St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, would not boo, even as a season was going down the drain. At the time, I wondered what Jacob deGrom, from central Florida, felt about that display of venom from Big Town? Was my question answered when deGrom took all that money from Texas and departed without one overt farewell or explanation or thank-you to Mets fans, at least one that crossed my consciousness? Whaever. I hope Jacob deGrom comes back -- in some vestige of that floppy youthful mop of hair and that nasty arsenal of pitches. Life owes him a few breaks. *** Roger Craig had a different kind of career. He turned up with the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers, tall and slender, ahead of that lefty from Brooklyn, Sandy Koufax. He helped win the World Series – in 1955, “This Is Next Year” -- and then he went west with the Dodgers and helped win the 1959 World Series. In 1962, Craig was part of the expansion team in New York that had to fill the awful Dark Ages void left by the Dodgers and Giants. Craig’s mellow North Carolina accent and kind disposition helped influence a clubhouse after too many losses. In 1963, on a losing streak of 18 games, Craig switched from his No. 38 to No. 13 and was the winner when Jim Hickman hit a grand-slam home run against the looming left-field stands. In those two epic formative years in the Polo Grounds, Craig left his mark on the club – as did Richie Ashburn formerly of the Phillies and Gil Hodges formerly of the Dodgers. Never underestimate experience and leadership. Let me say this about the Dodger presence, commemorated in Roger Kahn’s classic book, “The Boys of Summer,” about the Bums of Ebbets Field. That team had many strong personalities and mature leaders, including Pee Wee Reese from border-state Kentucky, who set a tone in the clubhouse. In the last months of Ebbets Field, Cap’n Pee Wee noticed a young outfielder, Gino Cimoli, showered and dressed and heading for the door, in the still-promising late afternoon. “Gino,” Reese drawled. “If you’re in a hurry to get out of the clubhouse, you’re in a hurry to get out of baseball.” Cimoli sat down, maybe had a beer, maybe chatted with Dodgers around him. The Brooklyn Dodgers were a true team. Roger Craig came along in that milieu, and he passed it along to a motley squad of “Amazing Mets.” He pitched and he often lost and talked baseball and looked the writers in the eye and answered questions. In 1964 Craig was liberated, helping the Cardinals win a World Series. Later, as a coach, he taught a generation of pitchers to throw a split-finger fastball. Later, Craig managed the San Francisco Giants to a championship -- courtly, wise, always remembering familiar faces from those epic 1962-63 season in the rusty old Polo Grounds. When Roger Craig passed, Ross Newhan, long-time baseball writer for the Los Angeles Times, wrote this on Facebook: “Roger Craig, the original Humm Baby, died Sunday at 93, and I couldn't be sadder. There was no manager's office I more enjoyed walking into, no spinner of stories I more enjoyed inscribing. He won two World Series as a pitcher with the Brooklyn Dodgers, moved to L.A, and eventually became manager of the dreaded Giants, who never seemed quite as dreaded with Humm at the Helm. He was quite the guy, and I know my sadness is shared by Corona's Marshall family, Michelle being his granddaughter and Riley his great granddaughter, both frequent visitors to his San Diego Counthome. RIP Roger, you were one of a kind.” I think I can speak for the writers from those years: Ross Newhan got it right about Roger Craig. ### As of this moment, the worst seasonal record in the history of the major leagues still belongs to the 1962 Mets – 40 victories, 120 losses, for a nice round percentage of .250.

However, it looks as if the Oakland A’s – 11-45- .196 as of Tuesday morning -- might break that record. A lot of people who love the Mets are rooting for Oakland to somehow avoid a new low, and leave that honor to Casey Stengel’s 1962 Amazin’ Mets. Is that twisted? Not from my point of view. The 1962 season remains memorable – the first season for an expansion franchise created to replace the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants, who had bolted to California in 1958. The Mets were often terrible, but they were also a lot of fun, with Stengel diverting attention from all those losses. Now, 61 years later, many Mets’ fans – and also some vintage Mets players -- are saying they could easily live with that distinction. “Keep the record!!!” texted Bill Wakefield, who had a decent year as a reliever in 1964. “I want that to be forever,” says Howie Rose, the Queens kid living out the dream by broadcasting Mets games on the radio. He will be honored by the Mets Wednesday evening and will throw out the first pitch – as fans display their Howie Rose bobblehead dolls. Rose goes back to 1962 when he was 8 years old and his father took him to the Polo Grounds to see the new team. “Being a narcissistic kid, I thought it was all for me,” Rose told me over the phone on Monday. The Mets beat the Cardinals and Gil Hodges hit what turned out to be his last home run. Rod Kanehl – the scrappy minor-leaguer who came to be a folk hero of the early Mets – hit the first grand-slam homer in Met history! Complete game by Roger Craig! Felix Mantilla 4-for-4! My man Joe Christopher playing center field! “It was a year-long celebration,” Rose said, noting that the Mets somehow won a World Series only seven years later. Amazing. “You had to be there,” Rose said. Craig Anderson was there at the start – a Lehigh College graduate, obtained from the Cardinal organization, one of the many “university men” that Casey and Edna Stengel relished. Anderson was the winning pitcher in both ends of a doubleheader against the Milwaukee Braves, raising the Mets’ record to 12-19. Maybe they were not so terrible, some people said. They promptly lost 17 straight, and finished the season at .250. Anderson was up and down with the Mets the next two years, and ended his major-league career with 19 consecutive losses – which was the record going into the 1992 season when another Met, Anthony Young, kept losing. “When Anthony Young approached my 19 straight losses,” Anderson texted Monday, “I wrote him and said I hoped he did not break my record, to no avail. He had good stuff and bad luck. I did the best I could but lost some starts when relievers failed me. So that’s baseball…” Anthony wound up losing 27 straight decisions with the Mets and Cubs, and died in 2017. Craig Anderson, 84, watches the Oakland Athletics stumble, as the A’s ownership allows the franchise to dwindle, to make it easier to get out of town, to Las Vegas. (And why not, given MLB’s dangerous new flirtation with sports gambling?) Some people would welcome another team breaking the Mets’ 1962 record. Keith Hernandez, who helped win World Series for St. Louis and the Mets, said on a TV broadcast last week that the Mets and their fans should be glad to get rid of the streak. But Craig Anderson is not so sure. He took heart from the old-timers’ day in Queens last summer, a lavish reunion including a few original Mets. Anderson added: “Don't forget a truly professional man, Gil Hodges, on and off the field!” “After the recognition that my teammates and I received last August, I truly feel about playing on the first Mets team was a special moment in my career,” Anderson continued, saying his team was “a small part of baseball history and Mets fans made us feel special too. “So let our record stand. Mets fans proved to me that former players, win or lose, are still special” -- Craig Anderson, 1962 Original Met, and Proud of It.” ###  Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Greatest Lacrosse Player, Ever Here on the Manhasset-Port Washington tectonic plate (if there is such a thing), some people still feel the rumbling from Jim Brown, local guy, who died Friday at 87. They remember the earth trembling when Brown crashed into opponents in most of his five sports. (Correct: five sports.) They also remember the impact of his loyalty, when he chose to come home to Long Island. Brown was many things to many people (including a felon serving a few months for misbehavior toward women.) Bad side and all, Brown was surely an epic figure out of ancient legends – from Beowolf to Babe the Blue Ox to John Henry, the steel-drivin’ man. Some people remember, first-hand. I called my pal and neighbor, Paul Nuzzolese, who played three sports at Schreiber High in Port Washington. Paul’s family used to run a visible ice-and-wood business with trucks rumbling all over the metropolitan area. Paul played guard in football, was on the basketball team, and was a lefty pitcher on the Port baseball team. The plan for Jim Brown was to throw off-speed, not give the big guy something he could hit. And if you could induce Brown to chop a grounder, it was wise to avoid a collision. Were baseball opponents intimidated by the sight of Jim Brown on the basepath? Paul called me back Sunday morning after he recalled pitching at home against Manhasset, and being taken out when the game was tied after a regulation seven innings. That gave him a good view of Brown's 360-foot perambulation of the bases: "Brown hit a squibbler down the first-line," Nuzzolese said. "You know how hard it is to field a squibbler." Harder with fully-grown Jim Brown hustling down the basepath. (No names mentioned of the Port fielders.) The ball got past the first baseman, into right field, and Brown took off for second, and continued toward third. The Port third baseman waited for the throw, but was wary of Brown barrelling down on him, and needless to say Brown wound up scoring on the aforementioned squibbler. Port lost the game, but the fielders retained their knees, and their wits. Still, like Jim Thorpe and Michael Jordan, Brown was not a great hitter. “It was his fourth sport,” Paul said respectfully on Friday when he heard his old opponent was gone. In order, Brown played football in the fall, basketball in the winter, was a high jumper in track and field, and somebody will have to explain to me how he managed to play baseball and lacrosse in the spring. There are tales of Brown playing in a baseball game, and when Manhasset was not in the field, he would leap a fence to and take a turn at the high jump, and then return and take his turn at bat. How did Brown come to Manhasset, at the base of Manhasset Bay, a few minutes from Port Washington? Born on Feb. 17, 1936, in coastal St. Simons, Ga., Brown came north with his mother, who cleaned houses in adjacent Great Neck. But Manhasset introduced the young man to civic leaders and coaches who promised him he would be comfortable in their school, and he wound up registered at Manhasset. He soon made himself felt – particularly on the football field. Paul Nuzzolese, 86, was a guard, bulked up over 200 pounds, who saw and felt Jim Brown up close. He recalls a fellow lineman -- “Big Joe, six-foot-three, built like Hercules, had a collision with Brown in the open field – never was the same.” My friend was talking on the phone from Florida; I could hear the shudder in his voice. (I have to proudly add: My pal Nuzzolese is now a member of the Wagner College athletic hall of fame.) As good as he was in football, Jim Brown was said to be the best lacrosse player who ever lived. It was impossible to dislodge the ball from the webbing at the end of his lacrosse stick, tight in his powerful hands. The legend is that Lefty James, the football coach at Cornell, wandered over to watch a Syracuse-Cornell lacrosse game one spring and blurted, “My God, they let him carry a stick?” (I think my late pal Dick Schaap, who played a bit of lacrosse, may have told me that story.) The money was in the National Football League, and Brown was the best, or very close to it. His path took him to the movies and some notoriety in his so-called private life and also a major role in Black activism of the ‘60s and well into this century. All of that is covered in the great coverage in Saturday’s New York Times and surely everywhere else. And then there were the homecomings. In 1984, Brown had mellowed enough to accept the induction into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, but obdurate as he was, he would only show up if the ceremony was held in his adopted hometown of Manhasset. He honored Ken Molloy, civic leader, and Ed Walsh, football coach, and others who treated him with respect, more than just a five-star athlete. I made the short drive to cover Brown’s induction. In the informal moments, I introduced Brown to my son, then 14 years old. “Nice to meet you, David,” Brown said, in that deep voice, shaking hands vigorously. I distinctly remember a crunching sound, although David does not quite remember it being quite that bad. Brown came home other times. One of his Manhasset teammates, Mike Pascucci, had done well in business, and had become a booster of one of the great institutions on Long Island, or anywhere – then named Abilities, Inc., now named the Viscardi Center, after the founder, Dr. Henry Viscardi – in nearby Albertson, L.I., where people are helped to work, to play, to live. (FYI: Edwin Martin, a frequent contributor to this site, was a long-time leader of the Viscardi Center and is a pioneer of services for the disabled; his wife Peggy has been an activist for easing young people into jobs.) Clearly, the Viscardi Center attracts good people. Once a year or so, Pascucci would invite his old teammate to visit the center. “They had a celebrity night,” Paul Nuzzolese recalled Friday, “They’d get athletes like Jack Nicklaus, Gale Sayers, Mike Schmidt, signing autographs. I saw Jim Brown get down on his knees and talk to those kids, and he would say how proud he was to be there.”  Jim Brown never lost his dedication to causes. I ran into him in the ‘90s, at some gathering in the city, I cannot remember the cause – health care and support for broken old football players, or racial causes. Whatever. Jim Brown was wearing a fez over his rugged skull, displaying a familiar hard look below the fez. Omigosh. I felt we were back in the late 60’s maybe in People’s Park in Berkeley, maybe outside Madison Square Garden or some other place that needed an attitude adjustment. The old days were back: Harry Edwards. Bill Russell. Roberto Clemente or Curt Flood giving writers a seminar in the clubhouse. Richie Havens. Nina Simone. Protest songs. The hallowed John Lewis. I saw a puzzled look on the face of a Black journalist, half my age, and I kind of giggled. Jim Brown’s scowl made me feel young again. And on the Manhasset-Port Washington peninsula, the earth still shudders from the powerful athlete who once played here. I can hardly wait to read the shop talk from Mark Landler, who does such a masterful job as the NYT’s correspondent based in London. Just the mention of coronations always makes me think of the great memoir of Russell Baker, who covered the 1953 ceremony for Queen Elizabeth, for the Baltimore Sun. (see below) Now, a great coronation output by Landler – my teammate during the Times’ coverage of the 2006 World Cup in Germany – on deadline, of the coronation of King Charles III on Saturday. (Landler was joined by a story on Queen Camilla by Megan Specia and a fashion Vanessa Friedman who has trained me to read her fashion essays.) Landler wrote a breaking news story with the lush details any Times reader would want – including, who was that lady in the blue-teal gown, carrying the sword? Why, it was Penny Mordaunt, the leader of the House of Commons – her very presence in the ancient ceremony another sign of inclusivity in not-your-grandparents’ England. Whether “we” should care about royals and coronations is another story. I checked, and my two rellies – Sam from the States and Jen from Australia – were not in their London base but rather in southwest France – and they were most decidedly NOT WATCHING. But I was, and so was the lady next to me, both of us with genes and family names and ancestry that go back to….well, in her case, William the Conqueror. (Me Mum was born in England but was decidedly a Churchill fan, not a royals fan.) Anyway, we gave the royals' production firm good marks for the visible Sikhs and Muslims and Buddhists plus the mention of Ephraim Mirvis, the UK grand rabbi, who was quartered near Westminster Abbey overnight to observe the Sabbath. (One favorite moment was the modern alleluia hymn sung and danced by the Ascension Gospel Choir, gracing the ceremony with their voices and their joy.) All of that was lavishly presented on the tube (anchored by Alex Witt, the weekend pro on MSNBC, with the indispensable Katty Kay back home in London, sending vital posts from a favorable spot on the parade route.) And soon the NYT will surely tell how its staff produced a masterpiece (color photos!) Speaking of shop talk: The landmark for coronation tales has less to do with young Elizabeth than with young Russell Baker, who had been posted in London by the Baltimore Sun, which in 1953 was a major, major American daily, always looking for young talent. Many decades later, as part of his memoirs, ("Growing Up" and "Good Times") Baker wrote about covering the 1953 coronation -- delightful details of how he scouted out a proper outfit for the ceremony, and how he packed a brown-bag lunch with two sandwiches and a few chunks of cheese and a tiny bottle of brandy to fortify himself during the long day. And how his wife, Mimi, was invited to a friend’s house where there was a TV set. Ever since Baker’s coronation tale was published, I consider it one of the inspiring great glimpses of a young journalist, being challenged by a great paper, and obviously succeeding, and how, decades later, Baker could recall the details of that assignment-of-a-lifetime. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/01/01/magazine/brown-bagging-it-to-buckingham.html **** Brown-Bagging It to Buckingham